Is religion a fixed, impassable boundary, or is it permeable and and expandable?

By Dr. Amandine Barb

Research Associate

Georg-August-Universität Göttingen

Abstract

Through the analysis of the status and perception of atheists in American history, from the colonial times to the beginning of the 21st century, this article explores the importance of religion in the structuring of Americans’ national and civic imaginaries. Starting from the assumption that atheists have always tended to be a distrusted minority in the United States, this essay seeks more precisely to explain how and why not to believe in God came to be regarded through the centuries not only as a moral and social deviance, but also as essentially “un-American” behavior. It further demonstrates that the historical “otherness” of the atheist tends to indicate that religion has functioned as one of the “moral boundaries” of a certain American “imagined community”, perceived as an essential warranty of both individual virtue and “good citizenship” and as a basic attribute of the American “self”.

Introduction

“Atheists are outsiders in the United States.”[2] Such was the title of an article written by Samuel Huntington and published in the Wall Street Journal in 2004. The Harvard political scientist explained that the United States was historically a nation of “Christians” and “believers”, and that therefore atheists could « legitimately see themselves as strangers » in American society. His assertion may appear exaggerated and provocative, but looking at various polls on public opinion and religion in the United States, it seems that Americans’ general perception of non-believers[3] confirms to some extent Huntington’s analysis. Indeed, two surveys from the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Lifeshow for instance that atheists are the only (ir)religious group that regularly gathers a majority of negative opinion.[4] In 2007, more than half of the respondents (53%) had an unfavorable perception of atheists (35% for Muslims and 27% for Mormons). Therefore, it appears that in today’s United States non-believers are a disliked minority, one that occupies – at least symbolically – a marginal place within American society.

The distrust towards atheism is of course not uncommon in history. As they do not consider themselves accountable to any higher power and do not believe in divine punishment after life, atheists have been stigmatized and rejected as immoral in various times and places. PlatoandThomas of Aquinasboth pleaded for the banishment – if not for the execution – of those who overtly refused to recognize a deity.The Enlightenment philosophers often considered unbelief as one of the exceptions to the religious tolerance they defended. John Locke argued that non-believers could not be accepted as legitimate members of the political community, since “promises, covenants, and oaths, which are the bonds of human society, can have no hold upon an atheist”, while Voltaire similarly refused to tolerate unbelievers, arguing that their lack of belief in God was a threat to society.[5] Yet, in today’s United States, such a popular distrust towards atheism seems at first sight surprising. Indeed, in American society, where the right to “believe and disbelieve” is strictly guaranteed by the 1st Amendment,[6] non-believers only represent a small minority – about 5% – of the population.[7] Therefore, this seemingly paradoxical and intriguing situation invites a deeper study of the status and perception of atheists, not only in contemporary American society, but also more generally in the history of the United States, in order to better understand how and why non-believers have come to be such a disliked minority, thought of by some as legitimate “outsiders”.

Penny Edgell explains that in a society, “the creation of [an] ‘other’ is always necessary for the creation of identity and solidarity”.[8] Charles Taylor similarly argues that in a democracy, the formation of “internal otherness”[9] and the process of (symbolic) exclusion are “by-product of the need (…) of a high degree of cohesion.”[10] Starting from these assumptions, it is crucial to analyze to what extent the atheist has played in the United States this role of a necessary “other”, one of the figures against which Americans have built and reinforced their collective identity throughout the centuries. To what extent has unbelief in the United States been historically categorized as a “stigma”, that is, in Erving Goffman’s terms, as an attribute which is “socially discrediting”, and considered as “abnormal” and “undesirable”?[11] It is then necessary to go further and to understand what this historical “othering” and stigmatization of atheism – its exclusion from what David Hollinger calls the “circle of the We”[12] – implies as for the importance of religion in the representations Americans have had of themselves and of their collective identity, i.e. their “imagined communities”?[13] In Money, Morals and Manners, Michele Lamont argues that societies are structured around “moral boundaries”, subjective lines that “we draw between ourselves and others” on the basis of core values and attitudes we consider as “essential”, and which “presuppose both inclusion (of the desirable) and exclusion (of the repulsive)”. These “moral boundaries” determine who is legitimate enough to belong and who is not – who are the “insiders” and the “outsiders”- at the level of both the private and the public spheres.[14] Following Lamont’s framework on “symbolic boundaries”, this article precisely seeks to demonstrate that the historical “otherness” of the atheist in the United States evidences the importance of religion as a strong private and public “moral frontier” in American society. It argues that throughout their history, Americans have used religion as a symbolic line of demarcation to distinguish between the individuals and the citizens deemed “desirable” and “trustworthy” (the believers) and those considered as “repulsive” and “unworthy” (the non-believers). In other words, this paper asserts, through the case-study of atheism, that religion in the United States has played the role of what Jeffrey Alexander calls a “symbolic code”, a value at the basis of “civic solidarity” and “critically important in constituting the very sense of society for those who are within and without it”:[15] the constant “othering” of non-believers, from the colonial times until today, reveals that religion has been commonly perceived as an essential warranty of both private and public morality – as a crucial criterion of individual virtue and “good citizenship” and as a basic attribute of the American “self”.

But eventually reflecting on the recent rise in the number of Americans who declare having “no religion” as well as on the new visibility gained by non-believers in American society over the last decade, this article will also assess to what extent religion is, to follow Michele Lamont’s distinction, a “guarded” – fixed and impassable – boundary, or, on the contrary, an “open” – permeable and expandable – “moral frontier”, which would make it possible to envision a greater acceptance of atheists in the United States in the near future.

The Historical Construction of the Atheist as the ‘Other’ in the United States

“Starting from this polluting fountain, I might trace the progress of vice and misery in a thousand narratives…how infidelity towards God leads to infidelity towards man and woman, destroys domestic peace and harmony, breaks up marriages, blunts the natural feelings and affections between parents and children, and dissolves families. I might show the origin of fraud in young men, of lewdness and prostitution in young woman”.[16]

To better understand how an “atheistic American” came to be understood as a “contradiction in terms” and what this negative perception of unbelief reveals of the importance of religion for civic belonging and collective identity in the United States, it is first necessary to study the theological, cultural and political patterns that have contributed, from the colonial times until the 21st century, to the constant “othering” of atheists from a certain American collective imagination: how and why not to believe in God came to be regarded throughout the centuries, not only as a moral and social stigma, but also as an essentially “un-American” behavior. Throughout this historical analysis, religion will clearly surfaceas a significant “moral boundary” – as a “principle of (private and public) classification and identification”[17] within American society – closely tied to the dominant ideals of morality and citizenship in the United States.

In American colonial society, as in John Locke’s England or in Voltaire’s France during the same period, non-believers – even though they were almost inexistent – were commonly loathed and feared. The figure of the “village atheist” pertained to the collective imagination, as that of an immoral and dangerous individual abandoned by God, unable to distinguish between good and evil, and condemned to be an eternal outcast, “detested, abhorred and despised by everybody, as pest and plague to society.”[18] In a traditional rhetorical script that became known as the “Jeremiad”,[19] religious and political leaders often instrumentalized this popular fear of irreligion to guarantee the social order and the unity of the community. Prophesying the decay of religious beliefs and the imminent spread of atheism almost became a kind of “cultural ritual”[20] among New England pilgrims, designed to guarantee religious, social and political obedience. John Winthrop, the Governor of the Massachusetts bay colony, often agitated the specter of atheism in his sermons, warning immigrants that a “laissez-aller” in their religious commitment could lead to the breach of the Covenant they had passed with God, and thus to the fall of the “city upon a hill” they had dreamt of building in their new land.[21] A century after Winthrop, during the first “Great Awakening” of the 1730s, the preacher Jonathan Edwards similarly warned people of the risks of religious indifference and enjoined them to turn to God in order to avoid a moral decay of the community.

Irreligion in Winthrop’s and Edward’s discourses was not only rejected as a religious fault, as an individual sin, but also and above all as a social and political offense that could have threatened the moral purity and the stability of the whole community. Atheism was therefore stigmatized as what Jeffrey Alexander calls a “civic vice”, i.e. an “impure”, “illegitimate”, and ”unworthy” social behavior that could have represented a potential “pollution” of the community – bringing immorality, licentiousness and anarchy – and thus that had to be legitimately “kept at bay”, on the margins of society.[22] As Alexander further argues, it is precisely “in terms of symbolic purity and impurity” that within a community, “marginal demographic status is made more meaningful”, and “centrality is defined.”.[23] Thus, in American colonial society, religion was already emphasized as a crucial individual, social and political value, as a “symbolic boundary” – one among many others – safeguarding the community from the danger of moral deviance and distinguishing between those who had the legitimacy to belong and those who did not.[24] It was, for instance, for the very purpose of avoiding a “pollution” of the community by potential irreligious individuals, that most colonies decided to limit their rights and their participation in the life of the polity. Atheists were traditionally prohibited from serving as witnesses in a trial or from being members of a jury.[25] A vast majority of the colonies also required candidates for public office to take a religious oath, thus excluding religious minorities (Quakers, Baptists, Presbyterians, Jews, etc.), when there was an established church, as well as non-believers in any case. In this regard, it is interesting to note that John Locke himself contributed to the political implementation of his philosophical rejection of atheism in the American colonies, when he took part in 1669 in the drafting of the “Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina”, of which Article 95 stated that overt irreligion was “illegal” on the whole territory of the colony: “No man shall be permitted to be a freeman of Carolina, or to have any estate or habitation within it, that doth not acknowledge a Lord and that God is publicly and solemnly to be worshipped.”[26] Belief in God became therefore in this particular case a requirement of the law itself, necessary, even if not sufficient, to be considered a “pure”, “virtuous” and legitimate member of the community.

After the War of Independence, some of the new American states similarly continued to impose restrictions on religious minorities and, of course, on non-believers, notably by requiring individuals to take a religious oath to testify in courts or to hold a public office.[27] Even in cases where the official church had been disestablished and religious liberty inscribed in the law, political authorities, convinced of the social utility of having religiously committed citizens, still tried to foster belief in God and an active religious practice, as exemplified in the Constitution of Vermont. Ratified in 1786, the text guaranteed complete religious freedom, but nonetheless explicitly stated that citizens ought to practice their faith, in order to maintain a “religious spirit” indispensable to the “moral purity” of the society. Chapter I, Article III affirmed that “all men have a natural and unalienable right to worship Almighty God according to the dictates of their own consciences (…). Nevertheless, every sect or denomination ought to (…) keep up some sort of religious worship, which to them shall seem most agreeable to the revealed will of God.” This official discouragement of religious indifference clearly indicates that religion was considered in Vermont – as in most of the new American states – as a necessary “civic virtue”, as a basic and essential attribute of the new republican citizen.

More significantly, this ambiguity between the necessary protection of freedom of conscience and the promotion of religion as a useful social and civic value was also salient at that time in the Founding Fathers’ thoughts on the place of religion in public life. Both the Federal Constitution of 1787 and the Bill of Rights of 1791, which they contributed to draft, by respectively prohibiting religious tests for federal public offices (Article 6) and the establishment of religion at the level of the national government (1st Amendment), made clear that belonging to the political community – citizenship – did not depend at all on a belief in God, and that the (federal) state could not legitimately use religion to distinguish between citizens. As James Madison wrote, “no man’s right is abridged by the institution of Civil Society and (…) religion is wholly exempt from its cognizance.”[28] All the more emphasizing the secular character of the new federal government, the founding document of the United States made absolutely no reference to Christianity, to God or even to a “Supreme Being” or a “Divine Providence”, as such was the case in the Declaration of Independence in 1776, leading many alarmed commentators to denounce the dangerous religious “infidelity” of the drafters.[29] And it is indeed true that, far from being pious Christians, some of the most important Founding Fathers – Franklin, Jefferson, Madison, and Adams – were closer to Deism, influenced by Enlightenment philosophers in their conception of a “benevolent Supreme Being” who created the world but did not intervene in human affairs.

Yet, even those “infidel deists”, who wrote and ratified a “Godless Constitution”, seemed to believe, as Locke did, that some sort of “religious spirit” was necessary to maintain a healthy republican society. Indeed, once elected presidents, George Washington, John Adams and James Madison regularly exhorted Americans to believe in God. Despite their deeply held conviction that the “business of civil government” was to be “exactly distinguished from that of religion,”[30] they still closely associated belief in God, morality, and “good citizenship” as three complementary qualities. Encouraging some kind of diffuse religious spirit was for the Founding Fathers a way to guarantee that people would have a minimum set of moral values, which they believed could contribute to make them more virtuous citizens, and more likely to respect the new laws of the young republic. Washington, in his 1796 Farewell Address, written by Alexander Hamilton, famously stated that it was unreasonable to believe that “national morality could be maintained in exclusion of religious principle.”[31] John Adams similarly wrote in 1798 that “our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious people”, one year after he had signed the Treaty of Tripoli, whose Article XI reaffirmed the secular character of the American Republic (“The American government is not in any sense founded on the Christian religion”). Jefferson, who was perhaps the only Founding Father who was openly willing to tolerate atheists, suggesting that they could be protected under the 1st Amendment,[32] allowed during his presidency the public funding of American Bible Societies. Created at the beginning of the 19th century by another Founding Father, John Jay, they were supposed to “promote the extension of true religion, virtue and learning” in order to “clean” the “impurities of our moral atmosphere”.[33] Therefore, it seems that even for the most skeptical Founding Fathers, religion appeared as one of the most useful warranties of “civic solidarity”[34] in a Republican society. Overt atheism, if it could not legally alter one’s status as an American citizen, was still to be discouraged as deviant social behavior, better confined to the margins of the Republic.

The stigmatization and “othering” of unbelief still continued to sharpen in the first half of the 19th century, as religion also began to play a central role in the building of a certain American identity. During this period, the United States was indeed characterized by a powerful movement of religious revivalism, the second “Great Awakening”. Evangelical sects started proliferating throughout the country, converting people massively in famous “camp meetings”, while romantic historians undertook the “Christianization” – or more precisely the “Protestantization” – of the American Republic. They heightened in their works the myth of a Protestant nation founded for religious reasons on religious principles by religious men.[35] More than being a “civic virtue”, religion became intimately linked with the history, culture and core values of the United States, thus gaining even more salience as a “moral boundary” in Americans’ collective imaginations.

In this context, where religious minorities such as Catholics were also stigmatized and discriminated against by protestant nativists,[36] irreligion, more than being a threat for the “moral purity” of the community and for republican values, came to be progressively castigated as “un-American” in essence. As religion became more and more integrated into “the ethos of American life”, unbelief “was becoming all the more inconceivable.[37] Thus, the figure of the atheist became increasingly associated, not only with the figure of the deviant immoral citizen, but also with the figure of the alien or of the nation’s enemy more generally. At the beginning of the 19th century for instance, atheism came to be systematically linked to the violence of the French Revolution. The writer Mercy Otis Warren expressed her fears that the “cloud of infidelity that darkened the hemisphere of France” could travel to the other side of the Atlantic and poison the American “national character, (…) free from any symptoms of pernicious deviations from the purest principles of morality, religion and civil liberty.”[38] Thomas Jefferson, who had lived in France during the Revolution, was accused by his Federalist adversaries and by Evangelical preachers of being an “atheist in religion”. Alexander Hamilton, in a series of articles entitled The Stand, repeatedly warned Americans against “French atheism”, particularly against the “political leader of the adherents to France”, the “pro-consul of a despotic Directory”, whose election as president would “destroy religion.[39] A Connecticut penman asserted even more categorically that “we are not Frenchmen, and until the atheistical philosophy of a certain great Virginian shall become the fashion (which God on his mercy forbid), we shall never be.[40]

This strong rejection of atheism and the importance of religion as a “symbolic code” – as a principle of social categorization and identification – , was noticed by Felix de Beaujour, a French diplomat assigned to Washington between 1804 and 1811, and who was surprised to discover that if Americans seemed indeed ready to accept almost “indistinctly” any kind of religious faiths or practices, “atheists alone [were] rejected”. He explained further that “[Americans] regarded [atheists] less as the enemies of God than of society”, (…) on the principle that the truth of each religion, individually, may be contested, but the utility of all is incontestable”.[41] Religion, as an indispensable basis for morality, “civic solidarity” and collective belonging in the United States, was thus more generally understood as an essential constituent of a certain Durkheimian “moral order”, i.e. of “a common public perception of reality that regulated, structured and organized relations in the community (…), (operating) less through coercion than through inter-subjectivity” and which contributed to “define the internal bonds” within American society.[42]

This crucial role of religion in 19th century American society was confirmed a few decades later by De Beaujour’s fellow citizen Alexis de Tocqueville, who also noticed that an individual who dared to express his irreligion publicly and – even worse – to criticize religious beliefs, was almost immediately despised and shunned by other Americans. In a comment that is still relevant today, he wrote that “in the United States, if a politician attacks a sect, this may not prevent the partisans of that sect from supporting him; but if he attacks all the sects together, every one abandons him and he remains alone.”[43] Tocqueville acknowledged that some Americans probably did not believe very sincerely in their faith: “I do not know whether all the Americans have a sincere faith in their religion – for who can search the Human heart?”. But he also judiciously remarked that the skeptics would always rather lie and say that they believed in God: “among Anglo-Americans, there are some who profess Christian dogmas because they believe them, and others who do because they are afraid to look as though they did not believe them”. Thus, in order to hide and to overcome their “stigma”, the non-believers met by Tocqueville felt compelled to resort to what Erving Goffman called the strategy of “passing”, i.e. pretending to be part of the “unstigmatized (religious) majority” in order to “gain social acceptance,”[44] an attitude that all the more testified of the “social desirability bias” of religion and of its strength as a “moral boundary” in American society.

The various trials for blasphemy that were held at that time in the United States give another meaningful illustration of the centrality of religion (Christianity to be precise), for a certain “moral order”. In various states, individuals were prosecuted for having denied the existence of God or for having attacked and insulted the Christian religion. Yet, blasphemy was not sanctioned for theological reasons – in order to defend the dogmas and beliefs of a specific faith – but rather because it served a secular purpose, i.e. guaranteeing public safety. In a country inhabited mostly by Christians, attacks against their religion – and thus their identity – could indeed potentially represent a source of conflict. When in 1837 the Supreme Court of Delaware condemned an individual named Thomas Jefferson Chandler for having declared that “the Virgin Mary is a whore and Jesus Christ a bastard”, the Judges clearly explained that the anti-blasphemy laws of the state were not designed to protect a faith in particular or even religion in general, but were necessary to preserve the unity and integrity of a community that such comments against its deeply held beliefs and identity could offend and divide: “The common law took cognizance of offences against God only when by their inevitable effect they became offences against man and his temporal security .”[45]

As mentioned earlier, non-believers were of course not the only religious minority despised and stigmatized in that way in 19th century America: to the sound of “anti-Popery” cries, Protestant nativists regularly attacked Catholic immigrants, accusing them of being a threat to republican values and questioning their loyalty to the American government. But in the first half of the 20th century, the American “circle of the We” started widening progressively, as religious minorities were increasingly being culturally, socially, and politically accepted into American society.[46] A 1959 Gallup survey testified of this process of inclusion, as 72% of Americans affirmed that they were ready to elect a Jewish President and 70% a Catholic, a result that was confirmed one year later by Kennedy’s victory.[47] Yet, this broader tolerance of religious diversity did not necessarily imply that religion as a “moral boundary” – as a standard of morality and “good citizenship” and as a basic attribute of the American “self”- was disappearing and becoming irrelevant in the United States. Indeed, while the 19th century Protestant nation was becoming a “Judeo-Christian” country, the atheist continued to be perceived and stigmatized as an unacceptable “other” in American society.

Its symbolic exclusion and its status of “outsider” even worsened during that period, when in the official rhetoric of the US government against the USSR, Communism and atheism came to be systematically associated with each other, conflated into the common figure of the anti-American enemy. In the language of religious and political leaders, the “godless communist” was often contrasted with the “religious American”. Joseph McCarthy declared for instance in a speech, that the “Christian world”, led by the United States, was facing the “atheist world”, dominated by the USSR.[48] Alluding once again to the “impurity” of atheism and to the risk of moral “pollution” it raised, American officials explicitly encouraged irreligious Americans to give up their deviant and “pernicious doctrine of materialism”, which, as the director of the FBI J. Edgar Hoover pointed out, “readied the minds of our youth to accept the immoral (…) system of thought [known] as communism”.[49] And it was for the very purpose of exacerbating the religious identity of the United States against the “cold” atheism of the USSR, that Congress decided to add “Under God” in the Pledge of Allegiance and “In God We Trust” on the dollar bills, respectively in 1954 and 1956.[50] A few years earlier, in 1952, senators, supported by President Truman – to whom Communism was the “deadly foe of belief in God and of all organized religions”[51] – had already decided to establish a National Day of Prayer. Their intention was to defend the United States against “the corrosive forces of Communism, which sought simultaneously to destroy [the American] democratic way of life and the faith in an Almighty God on which it was based.”[52]

Socially and politically marginalized since the founding of the first colonies, stigmatized as an immoral and dangerous citizen throughout the 19th century, the non-believer became the official enemy of the American Republic during the Cold War. Professing one’s irreligion – even in one’s private life – meant to symbolically break away from the rest of American society and to share the same values as the Soviet enemy. As Will Herberg wrote in 1955, “declaring oneself atheist, agnostic or even humanist” in the United States during that period, almost inevitably implied “being obscurely ‘anti-American’.”[53] During the Cold War, the stigmatization of the atheist as an “other” reached its climax: like Communism, unbelief was perceived as intrinsically incompatible – and irreconcilable – with the nation’s history, values and identity. Relegated beyond the boundaries of the “We”, the atheist, just as the Communist during the same period, could never be assimilated into the fabric of society and could only be imagined as a “dissident”, an “alien” or an “enemy”, fundamentally different from – and antagonistic to – the (good) American citizen. Religion clearly surfaced as a seemingly impassable “moral boundary”, separating the insiders from the outsiders (the atheists) – those “who did not share the core characteristics” of the “legitimate participants in the ‘moral order’ ” and against whom the symbolic “contours of American culture and citizenship were imagined.”[54] The “good American” was the “good believer”.

Beyond the Religious Boundary: The Difficult Mainstreaming of Unbelief in American Society

Despite being stigmatized as eternal “others”, a few American atheists, refusing to “pass” as believers, actually tried, throughout the centuries, to gain greater acceptance and visibility in American society. Using diverse rhetoric strategies and actions, those assertive non-believers have aimed at gaining a juridical, social and political “recognition”, while seeking a “mainstreaming” of atheism within American society in order to precisely “deconstruct” and untie the links between religion, morality, citizenship and collective identity the United States. From the beginning of the 19th century until today, they have attempted to “open” the “moral boundary” of religion and to render it irrelevant as a “symbolic code” and as a “principle of (private and public) classification and identification” within American society.

Claiming the legacy of illustrious skeptics such as Tom Paine, Elihu Palmer or Thomas Jefferson, American atheists, and “freethinkers” more generally, began to organize themselves as early as the 1820s, in order to defend their rights and their status in American society. Some of them, as the “Great Agnostic” Robert Ingersoll, managed to gain a cultural and political preeminence in the years 1860-1890, the period known as the “Golden Age of Freethought.”[55] Starting in the first half of the 20th century, they also regularly went to courts to protest against the real or symbolic support afforded by the state to religion, and to defend the constitutional protection of atheism, whose status under the 1st Amendment had long been controversial and unclear.[56] But, as Axel Honneth points it out, law is also often a primary tool for marginalized individuals or groups seeking recognition within society.[57] Therefore, American non-believers also used the courts as a way to gain a first legal acknowledgment in the United States and to demonstrate that one could indeed be a “full” citizen, with equal rights before the law, even without believing in God.

It was not until 1947 and the case Everson v. Board of Education that the Supreme Court officially confirmed that non-religion was protected under the 1st Amendment and that citizens were as free to profess their unbelief as they were to express their faith. Justice Hugo Black, writing the majority opinion for the Court, explicitly recognized the right not to believe in God: “Neither [a state nor the Federal government] (…) can force nor influence a person to go to or to remain away from church against his will or force him to profess a belief or disbelief in any religion. No person can be punished for entertaining or professing religious beliefs or disbeliefs.”[58] In 1952, in Zorach v. Clauson, the same Justice Black insisted once again on the necessity to include non-believers under the scope of protection guaranteed by the 1st Amendment: “The First Amendment has lost much if the religious follower and the atheist are no longer to be judicially regarded as entitled to equal justice under law.”[59] Justice Black affirmed in his opinion that even if one acknowledged that religion was intimately linked to the history of the United States and to the collective identity of its people, these facts did not give the state a legitimate right to privilege religion over non-religion under the 1st Amendment: “a people can be basically religious and their primary law and constitution can still afford equal rights to the irreligious.” Therefore, these two significant rulings emphasized the fact that religion – despite its recognized cultural, social, historical and political significance in the United States – could not legally function as a demarcation between citizens and could not legitimately be favored by the state to the detriment of non-religious individuals.[60]

But beyond their recognition under the 1st Amendment, all the legal disabilities that had been imposed upon atheists in American history since the founding of the first colonies eventually disappeared in 1961, when the Supreme Court decided that the provisions of some states’ Constitutions still requiring candidates to public offices to take an oath on God were a violation of the Establishment Clause. In Torcaso v. Watkins, the Justices ruled unconstitutional Article 37 of the Maryland Bill of Rights, which stated that “No religious test ought ever to be required for any office or profit or trust in this state, other than a declaration of belief in the existence of God”. Justice Black reaffirmed that the state could not “constitutionally pass laws or impose requirements which aid all religions as against non-believers.”[61] He suggested that the old popular fears against irreligion that had in some sense justified the inclusion of such tests in the 17th and 18th centuries were irrelevant in 20th century American society. According to Black and to the other Justices, the historical conceptions of unbelief as a “civic vice”, and of religion as an essential warranty of morality and “good citizenship” had no more legitimacy in the United States. Atheists could no longer be deemed less moral and less virtuous simply because of their lack of belief in God. They had to enjoy exactly the same rights as other citizens and be legally acknowledged as “worthy”, “moral” and “legitimate” members of the political community.[62]

Yet, some non-believers went even further in their attempts to challenge the moral ascendancy of religion and its importance for civic belonging and collective identity in the United States. They also started asking for the outlawing of the religious symbols in the public sphere, from “Under God” in the Pledge of Allegiance to “In God We Trust” on coins and dollar bills. They argued that even if those references to God did not threaten their rights as citizens, they still made it difficult for them to identify with the nation’s symbols, thus weakening their sense of belonging and giving them the impression that they were condemned to remain eternally beyond the “moral boundary” of the American citizenry. Associations of non-believers such as American Atheists or the Freedom From Religion Foundation sued the federal government and the local states on several occasions against these religious symbols. As of today, all their attempts have failed, as the courts have repeatedly argued, in the logic of a “passive secularism,”[63] that religious symbols in the public sphere do not amount to an establishment of religion since they have an obvious historical dimension, are non sectarian, and do not force anyone to believe or disbelieve.[64] In 2002, the decision of a California district court to declare unconstitutional the two words “Under God” in the Pledge of Allegiance after the complaint of an atheist, Michael Newdow, provoked very strong negative reactions on national level. Congressmen unanimously passed a resolution to maintain “Under God”, and dozens of representatives and senators gathered on the steps of the Capitol to recite the Pledge of Allegiance in front of cameras.[65]

These failed attempts of militant atheists to convince the courts that religious symbolism makes them feel like stigmatized “others” in their own country, directly illustrates the fact that despite the explicit legal recognition of non-believers’ rights under the 1st Amendment, to challenge and transcend the “moral boundary” of religion remains difficult in a country which considers religious faith an integral part of its “exceptionalism” and where almost 90% of the population declares believing in God and 76% in “life after death.”[66]

The persistence of religion as a core value still determining the contours of the “circle of the We” in the United States, is also confirmed by the fact that atheists tend to remain one of the most disliked minorities in today’s American society. Several surveys conducted since the beginning of the 2000s reveal indeed that in contemporary United States, unbelief is still considered a social and political stigma, and that religion continues to function as a strong “symbolic code” for private morality and good citizenship, central“in constituting the very sense of society” for a significant number of Americans.

A recent survey of the University of Minnesota showed, for example, that a significant part of the American population still thinks of the opposition between religion and atheism in terms of symbolic “purity” and “impurity”, and still considers a lack of belief in God as a moral disability.[67] 39.6% of the respondents affirmed, for instance, that atheists “did not at all agree with [their] vision of American society” – 10% more than for Muslims.[68] As Penny Edgell points it out, this result demonstrates that for many Americans, atheists still appear as “others”, with whom they do not feel linked by common values or a sense of belonging. Moreover, the fact that 47.6 % of the respondents said that they “would not like their child to marry an atheist” – 33,5% in the case of a Muslim – also indicates that for a large percentage of the American population today, atheists are more likely than religious people to be deviant and less trustworthy individuals. Thus, religion still appears to function as what Michele Lamont calls a “moral status signal” in today’s United States.[69]

But for many Americans, the atheist is not only a social misfit, he also remains a less reliable citizen, less “morally fit” than others to properly serve society and the common good, as seems to indicate the rather low percentage – 45% – who declared in a 2007 Gallup survey that they would be ready to elect an atheist for President.[70] The fact that this number has almost not changed for the last three decades – it was 40% in 1978 – whereas the acceptance of other groups has tended to increase over the years – with a few exceptions (for example homosexuals and Mormons), and thus that “in the face of rising pluralism and toleration, atheists alone have been left out in the cold”[71] seems all the more revealing and noteworthy. It confirms that in today’s American society, religion continues to be perceived as one of the basis of“civic solidarity” and of a certain “moral order”.

In this context, it does not come as a surprise that many Americans still tend to overemphasize their own degree of religious commitment. Sociologists have indeed noticed a significant difference between the percentage of people who declare that they go to church every week (about 40%) and the percentage of people who actually do – as observed by pollsters (about 20%).[72] This tendency of Americans to exaggerate their religious participation confirms that religion in the United States still carries a strong “social desirability bias”. Americans’ religious beliefs, practices and belongings may be becoming more and more vague, undetermined and porous,[73] but the positive “reputation”[74] of religion in general is still overwhelmingly strong: to believe in God remains perceived as a meaningful “civic virtue”, closely associated in collective imaginaries with the dominant conception of what the (good) American citizen is supposed to be.

Finally, it is even more striking to note that some avowed non-believers, having deeply interiorized the strong prejudices that exist towards them, still find it difficult to directly admit their religious indifference in the United States. Thus, they tend to downplay it. Alan Wolfe already observed in his study of middle-class Americans that “people who talked about their lack of belief in God did so hesitantly, even defensively, rather than as a self-proclamation.”[75] And according to a 2008 survey from the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life, only a small percentage – 24% – of those who declare that they do not believe in God actually refer themselves as “atheists”, a word that many find too negatively connoted, especially since the Cold War.[76] A majority of non-believers, when asked to categorize themselves, choose not to do so or prefer using more consensual, ambiguous and supposedly acceptable terms such as “humanist”, “freethinker” or “agnostic”, possibly as a way to “euphemize” their unbelief.[77]

The historical “otherness” of atheism and the strong prejudices that a significant part of Americans still hold against it would therefore indicate that religion is indeed a “guarded”, impassable “moral boundary” in Americans’ collective consciousness, still closely tied to ideals of private morality, citizenship and collective identity. Yet, the current transformations of the American religious landscape combined with the unexpected visibility gained by non-believers since the beginning of the 2000s could also suggest that a greater openness and acceptance towards unbelief is still possible in the United States, which would ultimately raise crucial questions and interesting hypothesis as for the resiliency of religion as a “moral boundary” and for its future as a relevant “symbolic code” in American society.

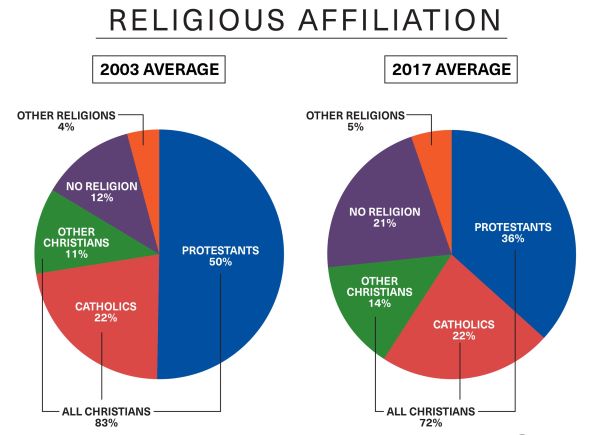

Over the past two decades, there has been a significant demographic change in the American religious landscape. The number of “unaffiliated Americans”, i.e. those who do not belong to any religious denomination, has been increasing constantly – though at a slower pace since 2000. Only 7% in 1990, they represent today 16% of the population. The fastest growing (ir)religious group in the United States – 22% of Americans aged 18-29 years declare being “unaffiliated”- they could reach 20% of the population by 2030.[78] While a majority of those Americans still believes in God or in a “higher power” (51%), they also tend to attach less importance to religion in their daily lives and in society in general.[79] A study led in 2003 by Michael Hout and Claude Fischer showed for instance that one of the reasons that led Americans to abandon their religious affiliation was a frustration towards the politicization of religion in the United States and the influence gained by conservative Christians.[80] In that sense, as Paul Lichterman points it out, the growing number of the “unaffiliated” could signal that “in many Americans’ eyes, religion’s reputation really may have suffered and declined” over the last decade.[81] It is therefore possible to suggest that in the coming years the “social desirability bias” of religion may also decrease in the United States. Less inclined to view it as a hermetic “moral boundary” and to use it as a “principle of categorization and identification” which presupposes the exclusion of an irreligious “other”, Americans would therefore also be less likely to view non-believers as necessarily morally deficient “outsiders”.

This hypothesis tends to be reinforced by the new visibility gained by avowed non-believers in American society since the beginning of the 2000s. From the surprising national success of several anti-religious books[82] to the growth of irreligious organizations throughout the country,[83] overt atheists have become more vocal and dynamic in the United States since G.W. Bush’s presidency, reaching an unexpected popularity.[84] Frustrated with the “God-talk” in American politics and tired of “being the last minority that it is acceptable to despise”, these militants have undertaken the task of overcoming the strong prejudices associated with unbelief, in order to challenge once again the link between religion, morality, civic solidarity and collective identity in the United States. Their first goal has been therefore to fight the social and political stigma of atheism. Following a logic of identity politics,[85] they have resorted to various types of initiatives to make their presence more visible in society and to increase public awareness of their situation as a symbolically marginalized minority, from marches on the Washington Mall to ads on buses. In 2009, in a nationwide campaign that received large media coverage, the American Humanist Association and the United Coalition of Reason placed posters advertising atheism on the buses and in the subways of almost every important American city. An ad in the New York City subway asked rhetorically “Millions of New Yorkers are good without God. Are you?”, while Manhattan buses stated similarly that “You don’t have to believe in God to be a moral or ethical person.”[86] The main aim of those peculiar “commercials” was, of course, for militant atheists to present unbelief not as a social anomaly but as a mainstream, acceptable behavior, shared by a significant part of the population. Other organizations like American Atheists have similarly called for non-believers to “get out” and to be more actively involved in the life of their neighborhoods, through such activities as “community service, blood donation or trash pickup”, as a way “to give back to society” and to show other people that one can be a “good citizen” even without believing in God.[87] Those assertive non-believers correspond to what Penny Edgell calls the “civically engaged atheists”, aware of the “negative stereotypes” against unbelief and who, as a strategy of “stigma management”, try to build a more “positive” image of themselves. As mentioned earlier, Jeffrey Alexander explains that a “civic vice”, in order not to “pollute” the community, must be confined to its margins. But it can also be “transformed, by communicative actions, into a pure form”, i.e. into a “civic virtue”. In trying to demonstrate to the rest of society that one can “be good without God”[88] and that unbelievers are “worthy” enough to be proper citizens, the new generation of atheists are precisely trying to transform their perceived “civic vice” or “stigma” – their lack of belief in God – into a positive, “pure” attribute that can be compatible with being a good American. They are reshaping and adapting what unbelief means in the United States, to make it better “fit” within the American mainstream. Therefore, provided that this mobilization does not only constitute a temporary backlash against the influence of religious groups in American politics, but manages to become established in the long run, it could also have a decisive influence on how most Americans view atheism. Along with the rise of the “unaffiliated”, this movement could progressively contribute to transform the dominant popular images of unbelief as a necessarily “Un-American” and dangerous “stigma”, which would make religion slowly appear as a less indispensable warranty of individual morality and civic solidarity in the United States, and thus as a more “open” boundary.

An important sign of a possible “softening” of the “moral frontier” of religion in 21st century America actually came on January 20th 2009, when Barack Obama declared in his inaugural speech “We know that our patchwork heritage is a strength, not a weakness. We are a nation of Christians and Muslims, Jews and Hindus – and non-believers”. This widely commented mention of “non-believers”, which could seem anecdotic to any foreign observer, was a meaningful gesture from the new president and marked a noticeable evolution in the place commonly afforded to unbelievers in the discourse of American political leaders. Historically forgotten or stigmatized as antagonistic to American values, they suddenly became recognized members of American society, besides other traditional religious groups – Christians, Jews, Muslims, etc. Obama’s phrase was not only an unprecedented official acknowledgment that atheists actually do exist in the United States, but also, and most importantly, that they are an integral part of the fabric of this society – of “our patchwork heritage”. One reader of the New York Times and self-avowed atheist even thanked Obama for at last “recognizing that we are Americans, too,”[89] while the director of NYC Atheists affirmed: “that one word legitimized us! It said we belong”.[90] The figure of the atheist, who had populated the nightmares of numerous generations of Americans since the first colonies, and who could only be considered as an “other”, became officially a mainstream American citizen by Obama’s speech. Criticized by Christian conservatives as an attempt to “redefine the distinctively Christian American culture”, considered by other commentators as the “most revolutionary phrase of the inaugural speech,”91 Obama’s reference to non-believers clearly signaled their first symbolic inclusion within the boundaries of the American “circle of the We”.And one can hypothesize that, as the number of “unaffiliated” Americans continues to grow in the coming years, and will thus represent a more significant percentage of the electorate, other politicians will follow Obama’s path and strategically take into consideration non-believers or non-religious Americans. And as they do so – and as non-believers gain more and more visibility in society – unbelief may finally start to slowly appear as less distant, “repulsive” and “abnormal”, perhaps diminishing the historical threatening “otherness” of atheists in some Americans’ eyes. Religion would thus also lose some of its importance as a “symbolic boundary” – some of its relevance as a “moral status signal” and as an essential criterion for individual virtue, citizenship and collective belonging in the United States.

Conclusion

The study of the status and perception of non-believers in the United States is eminently telling of the central place occupied by religion in Americans’ national and civic imaginaries. Throughout American history, from the first colonies to the beginning of the 21st century, the figure of the atheist has crystallized Americans’ religious, social, political and identity anxieties. Even as the acceptance of various other groups has increased, non-believers have remained significantly disliked and stigmatized by a majority of Americans until today. The nature of the prejudices towards them and the vocabulary used to characterize their lack of belief in God -“deviance”, “immorality”, “danger” and “vice”- stayed remarkably similar over the centuries. Demographically insignificant, atheists have been for a long time a convenient “other” – if not the only one of course – against which Americans could heighten and reinforce their sense of belonging and their collective identity, thus revealing the central role played by religion as a strong “symbolic code” and “moral frontier” in American society. Nevertheless, the current demographic and social trends concerning the place of “non-believers” in today’s United States should still let wide open the reflection and the discussion on the future of religion as a significant “symbolic boundary” in the United States.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Reverend George M. Docherty, pastor at the New York Avenue Presbyterian Church in Washington, 17 February 1954. Quoted in Stephen Bates, “Godless Communism and its Legacies”, Society 41/3 (March 2004): 1. A shorter version of this article was presented as a conference paper in Lille on 23 May 2010 at a workshop on American Studies (theme: “Looming on the Horizon”).

- Samuel Huntington, “Under God, Michael Newdow is right: Atheists are Outsiders in America”, The Wall Street Journal, 16 June 2004.

- For stylistic reasons, “atheist” and “non-believer” will be used as synonyms throughout this article, even though the meaning and connotation of these two terms can differ in the American context (not all Americans who declare that they do not believe in God identify themselves as “atheists”). To better understand the particular signification of these two words and the ways they are used in the United States, see Frank Pasquale, “The Nonreligious in the American Northwest”, in Ariela Keysar and Barry Kosmin (eds), Secularismand Secularity: Contemporary International Perspectives (Hartford: Institute for the Study of Secularism in Society & Culture, 2007); Bob Altemeyer and Bruce Hunsberger, Atheists. A Groundbreaking Study of America’s Nonbelievers (Amherst: Prometheus Books, 2005).

- See http://pewforum.org/Muslim/Views-of-Muslim-Americans-Hold-Steady-After-London-Bombings.aspx and http://pewforum.org/Politics-and-Elections/How-the-Public-Perceives-Romney-Mormons.aspx.

- John Locke, Letter on Toleration, 1689; Voltaire, “Athéisme”, “Athée”, Dictionnaire Philosophique, 1770.

- “Congress shall make no law respecting the establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.”

- “US Religious Landscape Survey,” Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life, February 2008. Among those 5% are those who declare that they “do not believe in God or in an universal spirit.” This article does not intend to be a historical or sociological analysis of American atheists: its main purpose is to study the perception and symbolical status of atheists in the United States. Thus, it will only explore to a small extent the nature and diversity of their (un)beliefs, the development of atheist organizations in American history, or the main historical figures of freethought in the United States. For detailed studies on those topics see Philip Hamburger, The Separation of Church and State (Cambridge: Harvard UPress, 2005); Susan Jacoby, Freethinkers. A history of American Secularism (New York: Owl Books, 2004); Evelyn A. Kirkley, Gender and American Atheism, 1865-1915 (Syracuse: Syracuse UPress, 2000).

- Penny Edgell, Joseph Gerteis, Douglas Hartmann, “Atheists as ‘Other’: Moral Boundaries and Cultural Membership in American Society,” American Sociological Review 72/2 (April 2006): 211-234.

- “Altérité intérieure”, cf. Audric Vitiello, “L’école et l’altérité : crispation identitaire et crispation institutionnelle,” Institutionnalisation de la xénophobie en France, REVUE Asylon(s), May 2008, available at www.reseau-terra.eu/article747.html

- Charles Taylor, “The Dynamics of Democratic Exclusion”, Journal of Democracy 9 (4) (October 1998): 143-156.

- Erving Goffman, Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity, (New York: Touchstone, 1963).

- David Hollinger, “How Wide is the Circle of the ‘We’? American Intellectuals and the Problem of the Ethnos since World War II,” American Historical Review 98/2 (April 1993): 317-337.

- Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities. Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism (London: Verso, 1983).

- Michele Lamont, Money, Morals and Manners. The Culture of the French and the American Upper-Middle Class, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992), 9.

- Jeffrey Alexander, “Citizen and Enemy as Symbolic Classification: On the Polarizing Discourse of Civil Society,” in Michele Lamont and Marcel Fournier (eds), Cultivating Differences: Symbolic Boundaries and the Making of Inequality (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992), 289-308.

- Arguments in the trial for blasphemy of Abner Kneeland, 1838. Quoted in Lori Ginzberg, “‘The Hearts of Your Reader will Shudder’: Fanny Wright, Infidelity and American Frethought,” American Quaterly 4/2 (June 1994): 205.

- Michele Lamont, Virag Molnar, “The Study of Boundaries in the Social Sciences”, Annual Review of Sociology 28 (2002): 167-195.

- Anonymous, “Sermon on Natural Religion by a Natural Man,” 1771, quoted in Owen Aldridge, “Natural religion and Deism in America before Ethan Allen and Thomas Paine,” The William and Mary Quaterly 54/4 (October 1994): 843.

- Sacvan Bercovitch, The American Jeremiad (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1978).

- See Wilson N. Brissett, “Puritans and Revolution: Remembering the Origin: Religion and Social Critique in Early New England,” in Charles Mathewes and Christopher McKnight Nichols (eds), Prophesies of Godlessness (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 22.

- See his sermon “A Model of Christian Charity” (also entitled “A City upon a Hill”), 1630.

- Jeffrey Alexander, The Civil Sphere (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), 46-64; “Citizen and Enemy”, 289-308.

- Jeffrey Alexander, “Citizen and Enemy”, 290.

- One must note however that Roger Williams, founder of the colony of Rhode Island in 1644 and famous advocate of religious liberty, broadened tolerance to those who did not believe in God (See Roger Williams, “A Plea for Religious Liberty”, 1644).

- Charles Rushing, “The First Amendment and Civil Disabilities imposed upon Atheists,” Duke Bar Journal 3/2 (Spring 1953): 137-154.

- Quoted in David Wootton, John Locke. Political Writings (London: Hackett Publishing, 2003).

- After 1783 six states of the thirteen kept an established Church. The last disestablishment occurred in 1833 in Massachusetts.

- James Madison, A Memorial and Remonstrance against Religious Assessments, 1785.

- The Anti-federalist Charles Turner warned in a pamphlet published in the early 1790s that “without the prevalence of Christian piety and morals, the best Republican Constitution [could] never save us from slavery and ruin.” When asked why there was no mention of God in the Constitution, Alexander Hamilton ironically replied “We forgot”. But this omission was deliberate: the delegate from Connecticut, Williams Williams, had suggested including a reference to God in the Constitution, but his proposition was quickly rejected.

- John Locke, Letter on Toleration, 1689.

- Quoted in Walter Berns, Making Patriots (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001), 39.

- Jefferson made several allusions to non-believers. He wrote for instance that “Locke refuses tolerance for those who deny the existence of God. (…). But where he stopped short, we may go on.” Quoted in Isaac Kramnick and Laurence Moore, The Godless Constitution. The Case against Religious Correctness (New York: W&W Norton, 1997), 92.

- Jonathan Den Hartog, “John Jay and the ‘Great Plan of Providence’,” in Daniel Dreisbach et.al. (eds), The Forgotten Founders on Religion and Public Life (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2009).

- Jeffrey Alexander, “Citizens as Enemy”, 289.

- See the works of Parson Mason Weems, The Life of Washington (New York: Belknap Press, 1809) and George Bancroft, History of the United States of America, from the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1834).

- Ray Billington, The Protestant Crusade (Chicago: Quadrangle Books, 1938); John Higham, Strangers in the Land. Patterns of American Nativism, 1860-1925 (New York: Atheneum, 1963).

- Will Herberg, Protestant-Catholic-Jew (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1955), 260.

- Quoted in Rosemarie Zagarrie, “Mercy Otis Warren on Church and State,” in Dreisbach et.al., The Forgotten Founders, 292.

- Quoted in Frank Lambert, The Founding Fathers and the place of religion in America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003), 93.

- Quoted in Jan Ellen Lewis, James Horn, and Peter S. Onuf, The Revolution of 1800: Democracy, Race and the New Republic (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2002), 178.

- Félix de Beaujour, Aperçu des Etats-Unis au commencement du XIXe siècle, depuis 1800 jusqu’en 1810 (Paris: L.G. Michaud, 1814); Georges J. Joyaux, “De Beaujour’s Views of America at the Beginning of the Nineteenth Century,” The Modern Language Journal 39/4 (April 1955): 165-173.

- Emile Durkheim, The Elementary Forms of Religious Life (New York: Free Press, 1965).

- Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America (London: Regnery Publishing, 2002), 243.

- Erving Goffman, Stigma, 1965.

- State v. Chandler, 1837. See Anonymous, “Blasphemy”, Columbia Law Review 70/4 (April 1970), 704, also quoted in Walter Berns, Making Patriots, 34.

- See of course Will Herberg, Protestant-Catholic-Jew, to understand how Catholics and Jews became progressively integrated within the boundaries of the American “imagined community” after World War Two.

- Frank Newport, “Americans Today Much More Accepting of a Woman, Black, Catholic, or Jew As President,” Gallup News Service, 23 March 1999.

- Joseph McCarthy, “Speech of Wheeling,” West Virginia, 9 February 1950. Quoted in Ellen Schrecker, The Age of McCarthyism (New York: Bedford Books, 1994).

- J. Edgar Hoover, “God and Country or Communism?” The American Mercury, December 1957.

- Louis Fischer and Nada Mourtada-Sabbah, “Adopting ‘In God We Trust’ as the U.S. National Motto,” Journal of Church and State 44/4 (Fall 2002): 671-692; Lee Canipe, “Under God and Anti-Communist. How the Pledge of Allegiance got religion in Cold War America,” Journal of Church and State 45/2 (Spring 2003): 305-323.

- “Text of Truman decrying ‘hysteria’ in fighting communists,” The New York Times, 11 November 1953.

- Quoted in “FFRF celebrates National Day of Prayer victory,” available at www.ffrf.orf, www.ffrf.org/news/releases/judge-rules-in-favor-of-ffrf-in-suit-against-national-day-of-prayer/. The National Day of Prayer is still acknowledged today by American Presidents, who since Reagan have traditionally issued a proclamation on the first Thursday of May. It was declared unconstitutional by a U.S District Court on 15 April 2010 after an atheist organization, the Freedom From Religion Foundation, sued the White House for violating the 1st Amendment. President Barack Obama decided to appeal the decision.

- Will Herberg, Protestant, 258.

- Michele Lamont and Laurent Thévenot, “Introduction: Towards a Renewed Comparative Cultural Sociology,” in Michele Lamont and Laurent Thévenot (eds), Rethinking Comparative Cultural Sociology (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 4.

- See Philip Hamburger, The Separation of Church and State (Cambridge: Harvard UPress, 2005); Susan Jacoby, Freethinkers. A History of American Secularism (New York: Owl Books, 2004).

- See Charles Rushing, “The First Amendment”, 1953.

- Axel Honneth and Nancy Fraser (eds), Redistribution or Recognition?: A Political-Philosophical Exchange (New York: Verso, 2003).

- Everson v. Board of Education of the Township of Ewing, 330 U.S 1: a New Jersey law allowing the reimbursement of public transportation for students attending catholic schools is constitutional.

- Zorach v. Clauson, 343 U.S 306, 1952: released time programs for religious education in public schools are acceptable if the instruction takes place away from the school campus, for one hour per week, and with no public funding.

- Since Everson and Zorach, these protections afforded to atheists under the 1st Amendment have been regularly reasserted by the Supreme Court in several rulings (Lynch v. Donnelly, 1984; Lee v. Weisman, 1989; McCreary v. ACLU, 2005). Some Justices in the current Supreme Court have nonetheless declared that they do not believe that the 1st Amendment prohibits the government from favoring religion over non-religion. Justice Antonin Scalia wondered for instance “how can the Court possiblyassert that “‘the First Amendment mandates governmental neutrality between … religion and non-religion’, and that ‘[m]anifesting a purpose to favor . . . adherence to religion generally’,is unconstitutional? Who says so? Surely not the words of the Constitution,” McCreary v. ACLU, 2005.

- Torcaso v. Watkins, 367 U.S 488. Two later rulings, O’Hair v Hill in 1978 and Voswinkel v. Hunt in 1979 confirmed that religious tests were unconstitutional, respectively for the Constitution of Texas and for the Constitution of North Carolina.

- It is worth noting however that as of today, three states – Arkansas, Tennessee and North Carolina – still have provisions prohibiting non-believers to hold public offices in their Constitutions, but they are of course only symbolic and would be ruled unconstitutional if enforced.

- Ahmet Kuru, “Passive and Assertive Secularism, Historical Conditions, Ideological Struggles, and State Policies toward Religion,” World Politics 59 (July 2007): 568-594.

- Some court cases were brought by militant atheists against religious symbols in the public sphere, but they all failed: Aranow v. United States, 1970 against “In God We Trust” on coins and bills; O’Hair v. Cooke, 1977, against the opening of Austin’s municipal council with a prayer; O’Hair v. Blumenthal, 1979, against “In God We Trust” on coins and bills; Marsh v. Chambers, 1983 (Supreme Court), against the opening of the sessions of Nebraska’s Congress with a prayer; Newdow v. U.S Congress, 2002, against “Under God” in the Pledge of Allegiance.

- Evelyn Nieves, “Judges ban Pledge of Allegiance from School, citing ‘Under God’,” The New York Times, 27 June 2002.

- Ronald Inglehart and Pippa Norris, Sacred and Secular. Religion and Politics Worldwide (New York: Cambridge Upress, 2004), 90-91.

- See Penny Edgell et.al., “Atheists as ‘Other’,” 2006, and http://www.soc.umn.edu/~hartmann/files/atheist as the other.pdf

- This result is of course all the more meaningful, since after 9/11 one could have legitimately expected a majority of the respondents to choose the category “Muslims”.

- Michele Lamont, Money, 57.

- See http://www.gallup.com/poll/3979/Americans-Today-Much-More-Accepting-Woman-Black-Catholic.aspx

- Charles Mathewes and Christopher McKnight Nichols, “Conclusion: Prophesies, in Retrospect and Prospect,” in Mathewes and McKnight Nichols (eds), Prophesies, 236.

- R.D.Woodberry, “When Surveys lie and People tell the Truth: How Surveys over-sample Church Attenders,” American Sociological Review 63/1 (February 1998): 119-122.

- Robert Wuthnow, America and the Challenges of Religious Diversity (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005); Loose Connections: Joining Together in America’s Fragmented Communities (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2002)

- Paul Lichterman, “Religion’s reputation”, The Immanent Frame, 2 February 2010.

- Alan Wolfe, One Nation After All (New York: Viking, 1998), 45.

- See http://pewresearch.org/pubs/1181/religious-identification-of-those-who-do-not-believe-in-god

- See the survey led by the anthropologist Frank Pasquale among groups of non-believers in the states of Oregon and Washington: Frank L. Pasquale, “The Non religious in the American Northwest,” in Keysar and Kosmin (eds); See also Ariane Zambiras, “Accepting the ‘Non –religious’? The Case of Atheists in the United States,” paper given at the conference Religion in the 21st Century: Transformations, Significance, Challenges, Copenhagen, 9-13 September 2007.

- Ariela Keysar and Barry Kosmin, American Nones: The Profile of the No religion Population (Hartford: Institute for the Study of Secularism in Society & Culture, 2008); Angela Abbamonte, “One in Five Americans may be Secular in 2030,” Religion News Service, Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life, 25 September 2009.

- Ibid.

- Michael Hout, Claude Fischer, “Americans with ‘No religion’, Why their Numbers are growing,” American Sociological Review 67/2 (April 2002): 165-190.

- Paul Lichterman, “Religion’s Reputation,” 2010.

- See Richard Dawkins, The God Delusion (London: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2006); Sam Harris, The End of Faith (New York: W.W. Norton, 2007); Christopher Hitchens, God is not Great. How religion poisons everything (New York: Twelve, 2007).

- The number of atheist or agnostic groups on college campuses doubled between 2007 and 2009, from 80 to 162 (Angela Abbamonte, “Atheist Groups Double in Size in Two Years,” Religion News Service, 16 September 2009). A national lobby, the Secular Alliance Coalition, has even been created to defend the interest of “non-theist” Americans in Washington (www.secular.org).

- David Abel, “The Nonbelievers”, Boston Globe, 16 September 2007.

- Richard Cimino and Christopher Smith, “Secular Humanism and Atheism beyond Progressive Secularism,” Sociology of Religion 68/4 (2007): 407-424.

- Daniel E. Slotnik, “Ads for Atheism appear on Manhattan Buses,” The New York Times, 25 June 2009.

- Jeffrey G. McDonald, “Long defined by what they are not, Nonbelievers increasingly try to define what they are,” The Christian Science Monitor, 28 June 2009.

- See the book Good Without God: What a Billion Nonreligious People Do Believe, written by Greg Epstein, Humanist Chaplain at Harvard Divinity School.

- Nicholas Kristof, “Obama’s Inauguration,” The New York Times, 20 January 2009.

- Michael Conlon, “A new day for U.S. atheists?” Reuters, 30 March 2009.

- Paul Levinson, “The most revolutionary phrase of Obama’s Inaugural Adress,” 20 January 2009, available at http://www.opensalon.cm

Bibliography

- Alexander, Jeffrey. “Citizen and Enemy as Symbolic Classification: On the polarizing discourse of civil society”, in Michelle Lamont and Marcel Fournier (eds). Cultivating Differences: Symbolic Boundaries and the Making of Inequality (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992), 289-308

- Alexander, Jeffrey. The Civil Sphere (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006)

- Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities. Reflections on the origins and spread of nationalism (London: Verso 1983, 13th edition, 2003)

- Anonymous, “Freedom of Religion, the Atheist, and the Torcaso Case,” Virginia Law Review 47/2 (March 1961): 315-329

- Anonymous, “Blasphemy”, Columbia Law Review 70/4 (April 1970): 694-733

- Aiello, Thomas. “Constructing ‘Godless Communism’, Religion, Politics, and Popular Culture, 1954-1960,” Americana: The Journal of American Popular Culture 4/1 (Spring 2005)

- Altemeyer, Bob, and Hunsberger, Bruce. Atheists. A groundbreaking study of America’s nonbelievers (Amherst: Prometheus Books, 2005)

- Bercovitch, Sacvan. The American Jeremiad (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1978)

- Bellah, Robert. “Civil Religion in America”, Journal of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 96/1 (1967): 1-21

- Berns, Walter. Making Patriots (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001)

- Caron, Nathalie. Thomas Paine ou l’imposture des prêtres (Paris: L’Harmattan, 1999)

- Cimino, Richard, and Smith, Christopher. “Secular Humanism and Atheism beyond Progressive Secularism”, Sociology of Religion 68/4 (2007): 407-424

- Dreisbach, Daniel, Hall, Mark, and Morrison, Jeffrye (eds). The Forgotten founders on religion and public life (Notre Dame, University of Notre Dame Press, 2009)

- Edgell, Penny, Gerteis, Joseph, and Hartmann, Douglas. “Atheists as ‘Other’: moral boundaries and cultural membership in American society”, American Sociological Review 72/2 (2006): 211-234

- Ginzberg, Lori. “ ‘The Hearts of your reader will shudder’: Fanny Wright, Infidelity and American Frethought”, American Quaterly 46/4 (June 1994): 195-226

- Hamburger, Philip. The Separation of Church and State (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2005)

- Herberg, Will. Protestant-Catholic-Jew (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1955)

- Hollinger, David. “How wide is the circle of the ‘We’? American Intellectuals and the problem of the ethnos since World War II,” American Historical Review (April 1993): 317-337

- Horn, James, Lewis, Jan Ellen, and Onuf, Peter (eds). The Revolution of 1800: democracy, race and the new republic (Charlottesville, University of Virginia Press, 2002)

- Hout, Michael, and Fischer, Claude. “Americans with ‘No religion’, why their numbers are growing,” American Sociological Review 67 (2002): 165-190

- Huntington, Samuel. “‘Under God’, Michael Newdow is right: Atheists are outsiders in America”, The Wall Street Journal, 16 June 2004

- Inglehart, Ronald, and Norris, Pippa. Sacred and Secular. Religion and Politics Worldwide (New York: Cambridge Upress, 2004, 8th edition, 2009)

- Jacoby, Susan. Freethinkers. A History of American Secularism (New York: Owl Books, 2004)

- Keysar, Ariela, and Kosmin, Barry (eds). Secularism and Secularity: Contemporary International Perspectives (Hartford, 2007)

- Kramnick, Isaac, and Moore, Laurence. The Godless Constitution. The Case against Religious Correctness (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1996)

- Kuru, Ahmet. “Passive and Assertive Secularism, Historical conditions, Ideological struggles, and State policies toward religion”, World Politics 59 (July 2007): 568-594

- Lacorne, Denis. De la Religion en Amérique. Essai d’Histoire politique (Paris: Gallimard, 2007)

- Lambert, Frank. The Founding Fathers and the place of religion in America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003)

- Lamont, Michelle, and Thévenot, Laurent (eds). Rethinking comparative cultural sociology (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000)

- Mathewes, Charles and McNight Nichols, Christopher (eds). Prophesies of Godlessness (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008)

- Rushing, Charles. “The First Amendment and Civil disabilities imposed upon Atheists,” Duke Bar Journal 3/2 (Spring 1953): 137-154

- Taylor, Charles. “The Dynamics of democratic Exclusion”, Journal of Democracy 9/4 (1998): 143-156

- de Tocqueville, Alexis. Democracy in America (London: Regnery Publishing, 2002)

- Wuthrow, Robert. America and the challenges of religious diversity (Princeton: Princeton UPress, 2005)

Originally published by the European Journal of American Studies 6-1 (Spring 2011), DOI:https://doi.org/10.4000/ejas.8865, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International license.