Works of art since ancient times have revealed the complexities of a wide range of gender identities and human couplings.

By Dr. Bryan C. Keene

Adjunct Professor of Art History

Pepperdine University

Queer and Trans Visibility in Art History

Do you see people who look like you or who identify as you do in these contexts? If so, when or where? What are their circumstances or aspirations? Are they named or nameless? For many members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, asexual, two-spirit, and a range of additional expressions of gender identity and sexuality (abbreviated as LGBTQIA2+), often we do not see ourselves reflected or respected in the past. Around the world today we face continued prejudice and persecution. These factors can make it hard to imagine we have a future. Queer and trans visibility in art history and museums saves lives.

Contemporary artists can be advocates for inclusion and change. They often draw inspiration from art(ists) of the past in order to present a vision for the future. One example is Kent Monkman, who is Cree and Scottish and identifies as two-spirit, a term used by some Indigenous folx to describe individuals who embody both masculine and feminine spirits and thus move beyond a gender binary. His work engages with long-standing European and North American histories of art by remixing historic compositions and incorporating Native peoples as protagonists. He also critiques legacies of colonialism, racism, homo/transphobia in the art world more broadly and museums in particular. For example, his large painting History is Painted by the Victors presents a poignant continuum of queer and trans history.

In Monkman’s painting, visual references to iconic of late 19th-century American art history abound: These include panoramic vistas by government-sponsored painter Alfred Bierdstadt, who documented the beauty of landscapes (the ancestral and current homes of countless Native communities) that would eventually be regulated by US state and federal laws, as well as scenes of white, settler, male intimacy outdoors by realist artist Thomas Eakins, known for homoerotic subtexts in his works. Miss Chief Eagle Testickle—Monkman’s alter ego—gazes directly at the viewer from the lower center of the canvas while painting an image of Crazy Horse and Northern Plains tribes defeating Lt. Colonel George Custer’s troops at the Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876.

One advantage of turning to contemporary art is that artists today—especially creators of color—are revealing vibrant and long histories of queer and trans presence that have otherwise been marginalized, censored, or erased. Mickalene Thomas, for example, reimagines nineteenth-century French painter Gustave Courbet’s canvas of two white women sleeping as an intimate scene between Black women.

By doing so, she challenges ideas about bodies and beauty, and aims to make headway into the “boy’s club” of individuals often championed in the art world. Thomas and Monkman both help us see the past anew and their work asks that we take a moment to unlearn harmful histories of hetero- and cis(gender)-normativity that have relegated the rainbow of LGBTQIA2+ and other historical identities to the shadows.

Heteronormativity and cisnormativity are concepts that assume heterosexuality and gender assigned at birth (cisgender identity) are normative or preferred modes of sexual orientation and gender identity, respectively.

One common misconception is that queer and trans history is fairly short or recent, limited to the last half-century in some cases or with a few early milestones in the late 1800s. Certainly the word “homosexual” (and by correlation “heterosexual”) was coined in the 1860s in Austria, and the Pride movements for gay, lesbian, and transgender rights were ignited in the 1960s in the United States, with the first march in 1970. And it is only recently that LGBTQIA2+ subjects and artists are slowly making their way into art history surveys, including the appearance of performance artist Cassils on the cover of Oxford’s After Modern Art: 1945–2017 volume. But our histories can be traced far back in deep time—to the origins of human creative output—and across the planet, if we know where to look. This chapter will introduce a range of historical case studies that hope to expand our ideas about historic gender and sexuality.

Queering Art History: Breaking from Western-Centered Narratives

Global art history from the paleolithic period to the present reveals kaleidoscopic ideas about human relationships and intimacy. Archaeology and anthropology are leading the way by introducing us to intersex and non-binary people, known now through DNA analysis and items found in burials. Indigenous communities and people in the global South (those south of the Equator, including communities in many former European colonies) are reclaiming identities that have long been suppressed, often violently. The Maori (of Aotearoa, the ancestral land known also as New Zealand) carved wooden box above, for example, shows fourteen different scenes of bodies engaged in sensual and sexual acts, including a central scene of a face receiving a penis in their mouth while their tongue reaches out to the vagina next to it. Other figures on the various surfaces embrace or kiss. These forms of expression are too often forgotten or purposefully erased from the historical record precisely because they have been and continue to be seen beyond conservative views (at times termed “traditional” or “normal”).

When I browse expensive print textbooks for art history or most museum gallery labels and websites, I see myself and others like me in the past through glimpses that are all too often marginalized, barely visible, or at risk of being essentialized in or erased from most presentations. On ancient Greek vase paintings, I sometimes see myself as a witness to the ancient Greek symposia, a gathering of men of myriad ages that might have involved acts of erotica, nakedness, and drinking (though I also recoil from their common imagery of older men molesting or preying upon younger boys).

Or I may see myself in the ancient Roman love story of emperor Hadrian and his paramour Antinous. In anecdotal “outings” of Renaissance and Baroque artists of the 1500 and 1600s, I am drawn to Michelangelo, who seems to have shown great affection toward the nobleman Tommaso dei Cavalieri, or to Caravaggio, who had relationships with multiple men, including Mario Minniti.

In the modern era, I find myself in the context of art produced in Andy Warhol’s circle (through examples by Jean-Michel Basquiat or Keith Haring) against the backdrop of the AIDS pandemic. The HIV/AIDS (human immunodeficiency virus / acquired immunodeficiency syndrome) pandemic was first recognized in 1981 and the epidemic remains ongoing.

And on rare occasions with examples from the history of photography, I see myself as in the mirror held by Magnolia, a non-binary muxe (a third-gender category in Mexico), in a gelatin silver print by Graciela Iturbide. This snapshot constitutes the limited range of queer examples from the past that may or may not be presented in survey texts. It is worth acknowledging that most of the examples in this paragraph constitute aspects of male sexuality.

European colonialism censured forms of identity that differed from a conservative view of male-female heterosexual, monogomus relationships and gender identity as solely that assigned at birth. There is still much work to be done to uncover or reinstate instances of female, trans, and non-binary experiences, especially those of communities of color. The following resources do not all explicitly present queer and trans narratives but can serve as a starting point for such conversations.

Historical Biology and Anachronistic Hetero/Cisnormativity

History is the record of the past that scholars and publics choose to remember. For example, the 4th-century B.C.E. ruler Alexander the Great consolidated territory in the Mediterranean and expanded the Macedonian and Greek empires into Western and Central Asia. Oral traditions passed down events from his life, including accounts that he had a range of lovers such as the young man Hephaistion and a eunuch called Bagoas. The Romans described his life in Latin texts, and throughout the Middle Ages, writers added to and updated his biography in every European language and some accounts from Persia to Ethiopia. In the 1470s, a Portuguese humanist named Vasco da Lucena penned a French account of Alexander’s life to serve as a model for Duke Charles the Bold of the Burgundian Netherlands and others at his court.

“In order to avoid a bad example,” the writer tells us that he regendered Bagoas and other male or eunuch lovers as female, thus introducing Bagoe (the feminized version of the figure’s name) to the narrative. The artist followed suit and juxtaposed Bagoe with the queen of the legendary Amazon warriors (depicted in the illumination in the background at right). For readers at the time, same-gender relationships were considered non-normative despite the prevalence of such couplings across all ranks of society and around the world, and powerful female rulers were also to be feared (in this European context). This version of history was precisely what its audience wanted but I wonder how such presentations of the past would be received today. We can look to film adaptations of Alexander’s life to see what this ancient figure means to viewers today. For example Oliver Stone’s 2004 Alexander included both Hephaistion and Bagoas, as well as female lovers, thus foregrounding the ruler’s fluid sexuality.

One of the challenges of wading through historical records is that people of the past have expressed a range of ideas about bodies, genitals, and the relationship (or not) between those physical aspects of an individual and their sexual or emotional attraction to others. Historical biology considers ways that people have understood bodies and their functions in the past, with ideas and beliefs that may seem quite different from those in the present. Widely understood today is that genitals do not equal gender. Genitals are an outward feature that doctors use to assign sex at birth: as female, intersex, or male. Gender identity is how an individual self-identifies and gender expression is their outward presentation of gender. Physical and emotional attraction can constitute a person’s sexuality. Scholars have long recognized the presence of individuals who do not fit into the simple and entirely modern categories of male and female, precisely because biological sex and societally constructed or prescribed gender are complex and varied, as we’ve seen. Let’s take a closer look at the sex spectrum with some historical examples.

In the 9th century B.C.E., the site of Hasanlu in present-day Iran was destroyed by fire. Amidst the remains is a pair of individuals known as the Hasanlu Couple (or Lovers). Evidence suggests that they are both biologically males, the one at left being about 30–35 years old and the one at right being about 19–22. Similar couplings have been found elsewhere in the ancient world, at Pompeii for example (where figures died from asphyxiation related to the smoke of Mount Vesuvius’s eruption). It’s problematic to read these figures as necessarily queer, however. Often popular media conflates gender, gender identity or expression, and sexuality, when each can be both determined by a specific time and place (culture) and by an individual. But this example reveals challenges posed to archaeologists when working with a binary of male/female and with an assumption that heterosexuality is normative (it’s not). The past was far more fluid.

The challenges in interpreting sexual acts of the past are clearly conveyed in ancient art from the Andes in South America. Ceramic vessels of the Moche and Chimú peoples include individuals engaged in a variety of sexual acts and positions, from masturbation to vaginal, oral, and anal sex. Setting aside preconceptions about sex and procreation, we can focus instead on what the objects depict and the frequency of their depictions in this media. In these instances, penetrative sex was varied and bodies were at times gendered male, female, or intersex based both on anatomy and on dress, hairstyle, jewelry, and more. Engaging with the past requires us to set aside ideas or biases about what may have been considered normative for a specific time and place.

The Egyptian pharaoh Amenhotep IV, who changed his name to Ahkenaton, is famous as the husband of Nefertiti and father of Tutankhamun. Ahkenaton is often described as having an androgynous appearance. Some archaeologists have posited that he may have had Kleinfelter’s syndrome, which might account for the enlarged breasts and also the shape of the pelvic bone. Some ancient rulers desired to present themselves as androgynous or to confirm their gender identity surgically, which was not the case, so far as we know, with Ahkenaten. Roman emperor Elagabalus, however, is sometimes considered a trans ancestor (or trancestor). The ruler is reported to have desired castration, a possible ancient equivalent of sex confirmation surgery. Some contemporary reports refer to Elagabalus using she/her pronouns.

The problematic term “hermaphrodite” comes from the ancient Greco-Roman deity Hermaphroditus, the child of the gods Hermes and Aphrodite, who is often represented with large breasts and a penis. Ancient artists at times sculpted this figure with the intent to fool the viewer into thinking they were viewing a cis-woman from one angle, only to see the penis from another angle. Numerous later artists—including Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Diego Velázquez, François Duquesnoy, and Barry X Ball—produced copies of the sculpture. This centuries-long ploy of attempting to “fool” the viewer denigrates intersex and trans bodies by making them objects of jest rather than dignifying them.

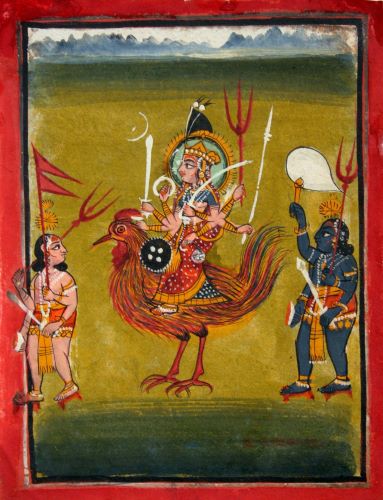

South and East Asian art offer several pathways for exploring gender fluidity. In Hinduism, Shiva and Parvati are two prime deities. When their natures are combined, they become Ardhanarishvara, an androgynous figure. Androgyny was considered one of the highest states in several cultures, as the perfect combination of male and female qualities. From India to China and beyond, Buddhists revere bodhisattvas, compassionate beings who forgo the release from suffering known as nirvana. One such individual is Avalokiteshvara (called Guanyin in China), who is alternatively represented as male or female or with varying features that defy strict gender categorization.

Archaeological finds, like the Hasanlu Couple, of individuals buried with objects that seem to transcend clear gender boundaries might point to the possibility of non-binary identity in the past. Burials around Stonehenge (England) have been described as male or female based on the presence of daggers or knife-daggers, respectively. At least one person was buried with both types of objects, as well as an amber necklace usually associated with female burials. Could this array of materials be a very early sign of expanded gender identity? Similarly, a Norse warrior was buried with objects associated with cisgender men (sword) and cis-women (lavish jewelry and clothing style), leading some scholars to suggest that they were a female warrior but more recent study suggests that the individual was intersex and had Kleinfelter’s syndrome.

Finally, several famous individuals—rulers, knights, religious figures, saints, and more—were assigned one sex at birth but changed their names and lived, dressed, and navigated society as the gender that matched their identity or to avoid the expectations for their assigned sex. Two such prominent figures are Alonso Díaz de Guzmán (assigned Catalina de Erauso at birth) and the Chevalier d’Eon (Charles-Geneviève-Louis-Auguste-André-Timothée d’Éon de Beaumont). After a time as La Monja Alferéz (meaning the standard-bearing nun), Catalina de Erauso took the names Alonso Díaz de Guzmán and alternatively Antonio de Erauso while traveling throughout Spanish territories. Questions continue to emerge about what pronouns to use to describe the individual and how they may have identified in terms of gender and sexuality. Similarly, the Chevalier d’Eon served in culturally male positions of diplomacy and military before fully presenting as female for the remainder of her life. She was famous in her time, amid rumor and speculation about her sex. Additional examples from the resources below expand the geographical scope of this survey by taking us to a few sites in the Americas, and also includes examples from Egypt, France, and French Polynesia.

Chosen Families in World Art History Today: Our Vibrant Past and a Limitless Future

The terms we use to describe ourselves today‚ as LGBTQIA2+ individuals—are part of an ever-expanding vocabulary of identity. An equally wide-range of related terms can be found in the material records of the past, sometimes used by people to describe themselves and at other times used derogatorily toward those with expansive ideas about gender and sexuality. Let’s look at a few examples from around the world.

In Sumer, a region of ancient Mesopotamia, priests referred to as gala may have constituted a non-binary gender identity: many were depicted in societally-defined male dress but were shown beardless and in texts were described with conventionally female characteristics. The term gala is made up of cuneiform, or wedge-shaped, signs meaning “practitioners of anal sex,” yet it appears that some had a wife and children (after all, anal sex is practiced by people regardless of sex or sexuality).

In ancient Rome, a gallus was a eunuch priest to the earth-goddess Cybele. These individuals were often referred to with the pronouns “she/her” but also derided as “half-men.” Eunuchs represent interesting case-studies in world history: they’re often described as asexual, due to the various forms of castration (in the case of the galli, some were self-castrated), but in other contexts are described with misogynistic language.

In many parts of western Europe during the medieval and early modern period, the term sodomite applied to any sexual act that did not lead to procreation (such as simply enjoying sex, solo or mutual masturbation, rubbing bodies or genitals together, oral and anal sex, sexual practices or assault in same-gender contexts, or an accusation of sex work by male-identifying persons). The association of sodomy as a male-to-male sexual relation punishable by death and condemnation to hell emerged in Dante Alighieri’s Inferno of the early 1300s. The poet encountered his mentor, Brunetto Latini, amidst a group of “sodomites” who offer a warning against the so-called “unmentionable vice.” Accusing a fellow citizen of sodomy was a common political tactic, and many European cities had laws regulating such activities and punishments if found guilty.

When writing about the Hundred Years’ War (1337–1453), Jean Froissart added a gossip-ridden aside about Jean, the Duke of Berry, noting that he was infatuated with a young man named Tacque-Tibaut who specialized in manufacturing knitted undergarments. Decades later, a manuscript illuminator incorporated the duke and his paramour in a royal throne room setting. The duke places one hand on the throne and one on the shoulder of the youth. These acts of historical “outing” has inspired art historians to look for possible queer readings in the objects commissioned by the duke.

Turning to premodern Mali in West Africa, we learn that Nommo are ancestral spirits who are described as androgynous or intersex. Gender transformation among followers of such deities is documented in more than twenty African societies prior to colonization.

In early modern Japan, the term Wakashu described adolescents who were assigned male at birth but who presented as female. They were understood as a third or separate gender category of their own, one that was sexually ambiguous, and they were attracted to and desired by men and women alike. They are recognized in art by the partially shaved crown of the forehead, which would be completely shaved once a cisgender male came of age after puberty.

For the Maori, the term Takatapui refers to an intimate companion of the same sex but can now refer to a full spectrum of queer couplings (including those who identify as heterosexual and have sex with members who identify as the same gender). The fluidity of sexual relationships on the treasure box mentioned earlier comes across clearly.

In India and South Asia, the term hijra can describe eunuchs, intersex or transgender people, or more properly a third gender or gender ambivalence. The word dates back to antiquity, with references in the Kama Sutra text on erotica and sexuality. Bahuchara Mata is one of the various Hindu deities who is a patron for trans communities in India.

As we saw at the start, in Indigenous American contexts the term two-spirit can refer to an individual who identifies with both traditionally masculine and feminine characteristics in reference to gender, sexuality, or gender expression.

This brief selection of terms hopefully serves to demonstrate that queer and trans people have always been present throughout time and across the planet. More and more such examples from art history, archaeology, anthropology, and other cultural studies of humanity continue to come to light. Teaching and learning about gender and sexuality liberates everyone from limiting categories of identity and shows queer and trans folx that we are valuable today and in the future.

Resources

- A Syllabus on Transgender and Nonbinary Methods for Art and Art History

- Women Artists

- Transgender Lives in the Middle Ages through Art, Literature, and Medicine by Roland Betancourt

- The Cluny Adam: Queering a Sculptor’s Touch in the Shadow of Notre-Dame by Karl Whittington

- Introduction to Gender in Renaissance Italy

- Confronting Power and Violence in the Renaissance Nude

- Copying as Innovation and Resistance

- Restoring Ancient Sculpture in Baroque Rome

- A Brief History of the Arts of Japan: the Edo Period

- The Case for Andy Warhol

- Graciela Iturbide: Photographing Mexico

- LGBTQ Histories in The British Museum (a Google Arts and Culture presentation)

Originally published by Smarthistory under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license.