Introduction

Poliomyelitis (polio) is an infectious disease that can cause spinal and respiratory paralysis. Children are particularly vulnerable to the disease, which used to be called infantile paralysis. There is no cure and if the infection affects the lung muscles or brain it can be fatal.

Polio has been around for a long time, but it was never considered a major problem until the end of the 1800s, when something unusual began to happen.

Polio Epidemics on the Rise

Like many other infectious diseases, polio spreads from person-to-person through the ingestion of faecal matter, often in food and water. But while improvements in sanitation such as clean water and sewage systems led to the decline of diseases such as typhoid and cholera at the end of the 1800s, outbreaks of polio began to increase.

The size and number of epidemics continued to increase in Europe and America throughout the first half of the 1900s.

A Polio Epidemic in New York City

On Saturday 17 June 1916, a polio epidemic was officially declared in the Brooklyn area of New York. The authorities responded aggressively to control the spread of the disease.

Every day the newspapers published the names and addresses of people identified with the disease. Placards were nailed to their doors and their families were quarantined.

Cinemas were closed, public gatherings were cancelled, and parents were told to keep children away from public places such as amusement parks, swimming pools, and beaches. Thousands fled the city to escape the epidemic.

That year, there were over 27,000 cases and more than 6,000 deaths due to polio in the United States, with over 2,000 deaths in New York City alone.

A polio epidemic appeared each summer in at least one part of the country, and major outbreaks became more frequent reaching their peak in 1952 in the USA, with 57,628 cases. Each summer was spent in fear of the disease. And there were similar situations across the rest of North America and Europe.

What Caused the Epidemics?

For centuries, protection from polio was passed down through the generations. Mothers who had survived polio infection themselves passed on immunity to their babies in the womb and through breast milk.

There are two stages to the polio infection. In the first mild stage the infection stays in the digestive system and throat and doesn’t reach the central nervous system. Most babies with maternal immunity are able to fight off the disease at this stage with only mild flu-like symptoms. At the same time, exposure to the first stage gives them their own long-term immunity.

But the unforeseen consequence of better hygiene and sanitation at the end of the 1800s was that babies in clean surroundings stopped encountering the infection while they still had maternal immunity.

So they failed to develop their own long-term immunity and were not protected when they encountered the disease later in life. And exposure to polio in late childhood or as an adult, was more likely to develop to the second, more aggressive stage of the disease.

The Symptoms of Polio

Second stage symptoms are more severe and include fever, muscle stiffness and headache, and maybe some temporary weakness or paralysis. The weakness or paralysis usually confirms that the disease is polio.

The author Philip Roth describes the frightening symptoms in his novel Nemesis, set in Newark in 1944:

Finally the cataclysm began – the monstrous headache, the enfeebling exhaustion, the severe nausea, the raging fever, the unbearable muscle ache, followed in another forty-eight hours by the paralysis.

In Roth’s story, everyone knows what polio is but no one knows where it comes from or how it is transmitted, and everything from flies to fast food are blamed for its spread.

In the second or acute stage, the infection reaches the central nervous system, where it begins to damage the cells that control the muscles (motor neurons). If 50% or more of the motor neurons are destroyed, then paralysis is permanent. This happened to about 1 person in 200. If the infection reaches motor neurons high in the spinal cord or in the brain, death could result.

The epidemic rise of polio led to renewed research into the disease and in 1908, Karl Landsteiner and Erwin Popper determined that polio was a viral infection. It was not until 1953 that the poliovirus that caused the disease was actually seen through an electron microscope.

Treatment and Rehabilitation

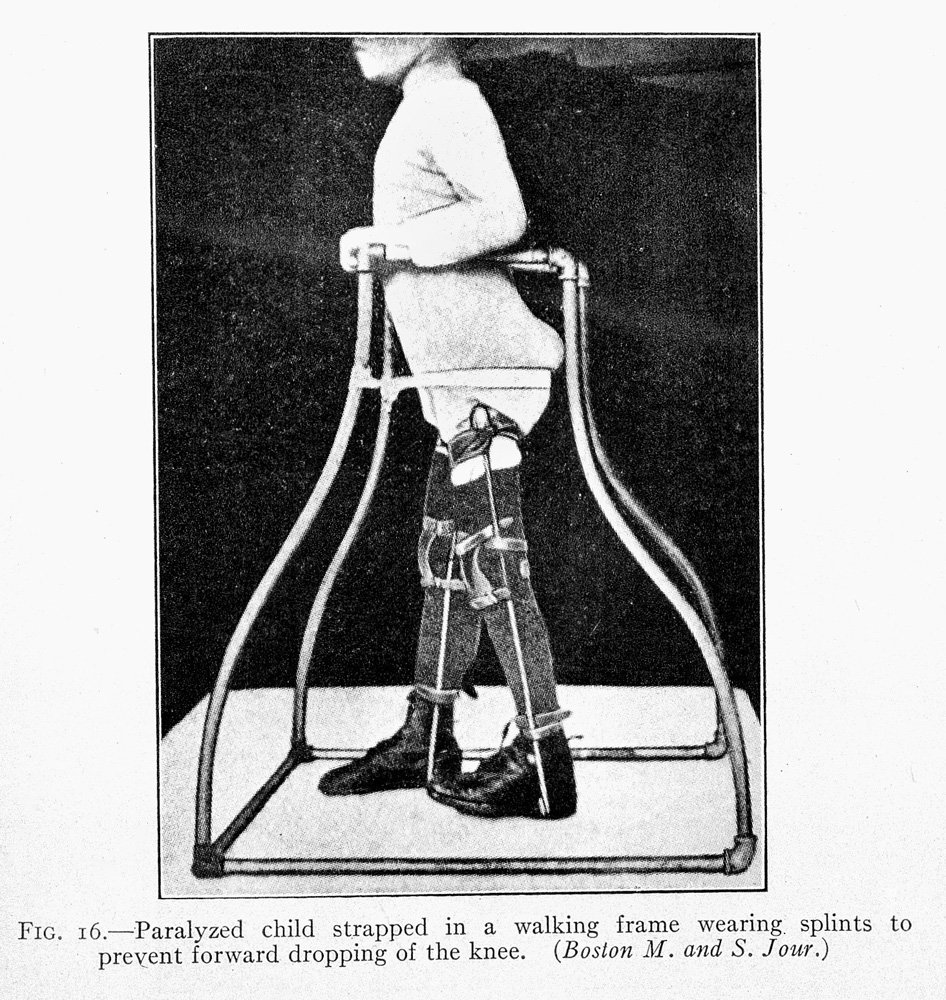

Early treatments for paralyzed muscles advocated the use of splints to prevent muscle tightening and rest for the affected muscles. Many paralyzed polio patients lay in plaster body casts for months at a time. But long periods in a cast often resulted in atrophy of both affected and healthy muscles.

Treatment of polio was revolutionised in the 1930s by Elizabeth Kenny, a self-trained nurse from Queensland, Australia. Kenny developed a form of physical therapy that used hot, moist packs and massage and exercise and early activity to maximize the strength of unaffected muscles and stimulate the remaining nerve cells that had not been killed by the virus.

Kenny later established the Sister Kenny Rehabilitation Institute in America and by the mid-1900s her therapy was the accepted treatment for paralytic polio. And it is still used today.

Polio is a very painful disease and the recovery could take years of agonising rehabilitation to regain the use of arms and legs. Philip Roth described his character’s experience in 1944:

He underwent four torturous sessions of the hot packs a day, together lasting as long as four to six hours. Fortunately his respiratory muscles hadn’t been affected, so he never had to be moved inside an iron lung to assist with his breathing, a prospect that he dreaded more than any other.

The iron lung was developed in 1928 for patients whose lung muscles were paralysed so they could no longer breath unaided. Most patients only had to spend a short period in the iron lung before they regained the use of their lungs. But some patients with permanent paralysis of the lungs had to stay encased up to their necks in the large cumbersome contraptions for the rest of their lives.

Polio Vaccines

With no cure for polio, research efforts were focussed on developing a vaccine to prevent the disease. The first polio vaccine was developed by Jonas Salk, with the help of funds from the March of Dimes.

In 1954, Salk launched what was then the largest human medical trial in history, injecting nearly 2 million American children with a potential vaccine. The Salk vaccine, or inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV), contained a deactivated form of the poliovirus and was administered by injection.

Immediately following licensing in 1955, a mass vaccination campaign was launched. The effects of vaccination were dramatic. More than 38,000 polio cases were reported in 1954 in the United States. After just five years of vaccination, the number of paralytic polio cases had dropped to 2,525 in 1960.

Eight years after Salk trialled his vaccine, Albert Sabin developed an oral polio vaccine (OPV) using live but weakened (attenuated) virus. Sabin couldn’t gain political support in the U.S. for what he viewed as his superior vaccine. So, at the height of the Cold War, he tested it in the Soviet Union, which had also suffered a major polio epidemics.

In 1958, the Soviet Union organized industrial production of the OPV vaccine and polio began to decline in Eastern Europe and Japan. This success led the United States to license Sabin’s vaccine in 1961.

Both the Salk and Sabin vaccines are still used today. But Sabin’s OPV, which requires just two drops in a child’s mouth, proved much easier to use in mass immunization campaigns and gave life-long immunity.

By 1961, only 161 cases of polio were recorded in the United States. By 1988, polio had disappeared from the US, Australia and much of Europe but remained prevalent in more than 125 countries. The same year, the World Health Assembly adopted a resolution to eradicate the disease completely by the year 2000.

Eradicating Polio

The World Health Assembly did not meet its millennium target, but by 2012, endemic polio remained in just four countries—Afghanistan, Nigeria, Pakistan and India.

But epidemics don’t respect national borders. In 2011 the infection crossed the border from Pakistan – a decade after China was officially declared polio-free. China regained its polio-free status once the outbreak was brought under control.

India’s National Immunisation Days, dedicated to the fight against polio, began in 1995. Within two decades annual cases of the disease were down from over 3,000 to none. India was officially declared polio-free in 2014.

The world is even closer to being polio free, with endemic polio remaining in just two countries—Pakistan and Afghanistan. But until the infection is eradicated from every population in the world, the threat of epidemics remains, thanks to global transport networks, and immunisation has to continue.

Originally published by the Science Museum UK, 10.15.2018, republished with permission for educational, non-commercial purposes.