By Mikaela Lefrak

Reporter, Arts and Culture

WAMU American University Radio

Introduction

The coronavirus pandemic has created what feels like an unprecedented situation in the District: Schools are closed, hospital workers are overwhelmed and the region’s iconic public spaces are empty.

Coronavirus isn’t the first global health crisis D.C. has faced. During the 1918 influenza epidemic, the nation’s capital was one of the hardest-hit areas of the country. Just like today, the city had to shut down schools, churches and recreational facilities to stop the spread of the virus. And just like today, doctors, nurses and average citizens stepped in to help.

Here’s how Washington’s last major epidemic progressed.

Part I: The Illness Arrives

Word of the pandemic first reached Washington in the early fall of 1918. Louis Brownlow, the president of D.C.’s commissioners (kind of like the mayor, before home rule), received a telegram from a health official in Boston. It described a mysterious flu strain spreading through the city. Brownlow described his friend’s warning in his 1958 autobiography, “A Passion for Anonymity”:

…neither he nor anybody else in Boston knew what to do about it; that he was afraid it would be particularly severe if it reached Washington on account of the terrific overcrowding in the capital and he thought the commissioners ought at once to make the new disease reportable.

Nearly 20,000 people had moved to D.C. during World War I, which was just reaching its conclusion when the flu epidemic hit. D.C.’s population was around 400,000 people at the time.

According to recent research by local historian Matthew Gilmore, the region’s first recorded influenza death was a man named John William Clore, a railway worker from Culpeper who died at Sibley Hospital on Sept. 28, 1918.

Health officials still weren’t taking the illness seriously. Scientists hadn’t yet discovered flu viruses and, per the CDC, there were no antibiotics to treat secondary bacterial infections associated with the flu.

The prominent city health officer William Fowler advised Washingtonians to “sleep with your windows open and you will be in little danger” just two days before Clore’s death.

Part II: Reality Hits

The situation quickly escalated, and the city’s leaders were forced into action. In early October, Commissioner Brownlow ordered that all doctors in the city report any new or suspected cases of the “Spanish influenza,” as the virus was known.

So many cases were reported that the system “utterly broke down” within 10 days, Brownlow wrote. Three hundred and eighty-seven people were reported dead of influenza during the first week of October.

Brownlow closed the city’s schools, theaters, churches “and for a few days all mercantile houses except grocery and drugstores” — just like D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser’s recent order to shut down all nonessential businesses.

And in a parallel to today’s pop-up coronavirus testing facilities, government officials set up temporary “nursing centers” in D.C. schoolhouses. People who were in contact with sick patients would be fined up to $100 if they went out in public.

Public transportation proved to be a major issue. Half of the city’s streetcar workers were sick, so the federal government agreed to stagger federal workers’ hours to reduce the demand.

Part III: Hospitals Become Overwhelmed

“Every physician had too many cases, and there were not enough physicians in the city to begin to care for the thousands who were stricken,” Louis Brownlow wrote about that terrible October.

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s recent pleas for more health care workers echo Brownlow’s desperate search for healthy doctors and nurses. All the beds in the city’s hospitals were full, and there were no nurses available for shifts. The city was also running low on gravediggers and coffins.

The city started to get scrappy. Brownlow commandeered an empty building at 18th Street and Virginia Avenue NW, just off the National Mall. He ordered the owners of department stores and furniture stores to assemble 700 units of bedding and assembled a skeleton crew of doctors and nurses. He claims it took him just 24 hours to get the temporary hospital up and running.

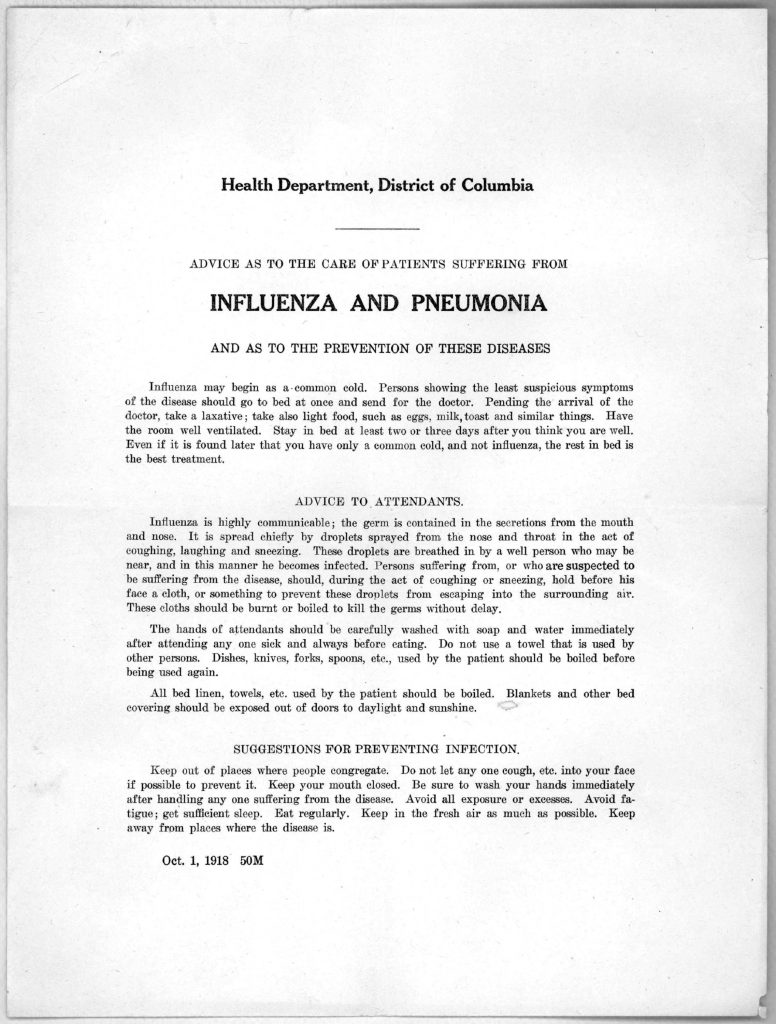

Unfortunately, the prevention and treatment methods of the time were not as effective as they are today. Advice in the city-issued health memo above ranged from broadly practical (“Do not let any one cough, etc. into your face”) to useless in hindsight (“Pending the arrival of a doctor, take a laxative”).

A newspaper article in the “Evening Star” recommended drinking hot lemonade or eating raw onions.

And just like today, protective masks became increasingly difficult to find. An “Evening Star” article from October 20, 1918 suggested making masks at home from gauze or cheesecloth and tape.

Part IV: Recovery

Both Brownlow and his wife eventually contracted influenza, too. Their cases weren’t severe, and they were nursed back to health by a policewoman who had been trained as a nurse.

“The worst was over,” he wrote:

The deaths decreased. The cases decreased. While we had to continue for several weeks to operate the complicated emergency machinery we had set up, the end finally came. The plague lasted from September 21 to November 4.

Schools and churches reopened in early November, a decision that was perhaps made too hastily. While the number of influenza cases peaked in October 1918, Gilmore’s research shows that smaller outbreaks cropped up again and again for the next two years. President Woodrow Wilson was even thought to have contracted the flu while participating in peace talks in Paris in 1919.

All told, D.C. proper reported about 35,000 influenza cases between October 1918 and February 1919 and 3,500 deaths — a 10% mortality rate. Thousands more cases probably went unreported. The mortality rate for people sickened by coronavirus today is around 1.38%, according to a new study in the medical journal Lancet.

But the story isn’t entirely grim. During the epidemic, local Girl Scouts set up kitchens at Central High School (now Cardozo High School) and an M Street YWCA to feed people sick with the flu. Doctors and nurses saved countless lives. And the city did, eventually, recover.

Originally published by WAMU 88.5, American University, open access, shared for educational, non-commercial purposes.