Their first one hundred years.

Curated by Hillary Brady

Former Digital Content Specialist

National Air and Space Museum

Smithsonian Institution

Curated by Dr. Franky Abbott

Curation and Education Strategist

Digital Public Library of America (DPLA)

Introduction

For many Americans, their fondest memories revolve around a library card. From searching through the stacks, to getting a return date stamped on the back of a new favorite book, libraries are a quintessential part of how Americans learn and engage with their local communities. Since this country’s founding, public libraries have received broad and consistent popular support for their democratic missions and services. The ability to access free information has become a core ideal of what it means to be an American citizen, despite periods of historic inequality. Libraries help make this access possible by placing public benefit at the center of their work and continually adapting their strategies to meet changing public needs over time.

This exhibition tells the story of the American public library system, its community impact, and the librarians who made it possible—from the founding of the first US libraries through the first one hundred years of service.

Beginnings

Overview

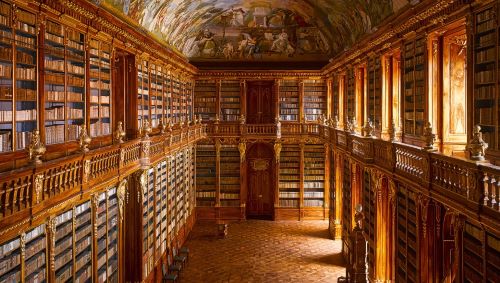

Before public libraries spread across the United States after the Revolutionary War, people were looking for outlets to access and discuss literature. During the Enlightenment, these came in the form of literary salons, which gained popularity in France and Italy. Salons were spaces for conversations about art, politics, and literature. They were particularly empowering for women, who had been barred from formal learning spaces and now had a place to exchange ideas, read and share their writing, and debate. Decades later, libraries offered a similar opportunity for women to enter the workforce and academia in new ways, too.

With the rise of non-religious texts and literacy rates in the 1700s, private book clubs among wealthy men evolved into subscription libraries. Subscription, or membership, libraries were funded by membership fees or donations, with collections accessible only to paying members. While today there are fewer than twenty membership libraries in existence in the US—many of which focus on special collections or rare material, rather than a varied book selection—from the late 1700s to the mid-1800s, they sprang up in cities across the country. The first of these libraries was formed in Philadelphia, under the direction of Benjamin Franklin, and would come to be known as the Library Company.

The Library Company

In pre-Revolutionary War America, books were hard to come by for anyone who was not wealthy or a member of the clergy. The expense and rarity of books meant that members of the middle or lower classes did not readily have access to reading material.

That changed in July 1731, when Founding Father Benjamin Franklin helped bring the membership library to the American colonies. Franklin worked with the other members of what was called the Junto, a club of thinkers that gathered to discuss “queries on any point of Morals, Politics, or Natural Philosophy,” as Franklin described in his autobiography. Franklin and the other Junto members, primarily merchants, owned few books and were looking for a way to access more material for their weekly discussions.

Using money from the Junto members, alongside a forty-shilling investment from each of the library’s first fifty members, Library Company organizers started its first collection. By 1732, they had sent the library’s first book order to London. Though many of the library’s early books were about education or religion, the collection expanded to feature broader topics. Notably, a majority of the Library Company’s books were written in English. (At the time, most other private and university libraries had collections primarily in Latin.) Library members could access these books as they pleased, while non-members would need to provide collateral for their borrowed book.

First Public Libraries

In addition to membership libraries, Benjamin Franklin also played a role in the development of the first lending library. In 1790, Franklin donated a collection of books to a Massachusetts town that named itself after him. Though the town asked Franklin to donate a bell, he determined that “sense” was more important than “sound.” Franklin residents voted for those donated books to be freely available for town members, creating the nation’s first public library.

Public libraries began spreading in earnest in American towns and cities after the Civil War. These lending libraries are defined as board-governed and tax-funded instead of operated under a subscription model. Most importantly, they are open to all, do not charge for their services, and focus on serving the needs of the general public.

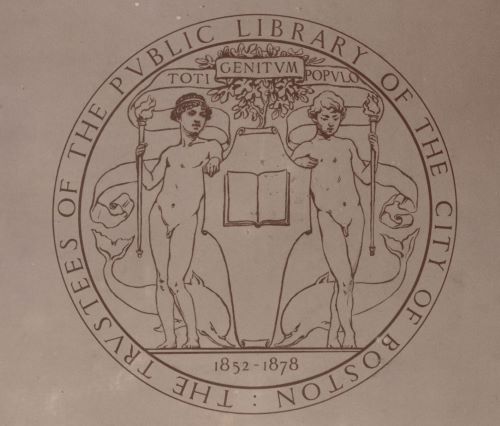

The first totally tax-supported library was established in Peterborough, New Hampshire, in 1833. While there were many other libraries that met new public-oriented milestones—like the Darby Free Library in Pennsylvania, which has been in continuous service since 1793—the first large public library was the Boston Public Library, founded in 1848. Boston Public Library opened in 1854 and all Massachusetts residents could borrow from its collection, which began with 16,000 volumes.

A Profession for Women

Overview

Men from New England’s elite families were the predominant players in the early US library movement. These men viewed librarians like missionaries, bringing civilization and reform to the masses through educational opportunity. Many were well-connected graduates of New England’s colleges and some had departed other careers in law and ministry to begin second careers as librarians. Along with these men, a number of women from the elite classes volunteered at libraries, particularly for work with children. It was not until after 1900 that women would dominate the operational work of libraries, and longer still until they would have full administrative power and responsibility.

This particular gendered history underpins the founding of the American Library Association (ALA)—the first and largest library professional organization in the world. In 1876, 103 librarians from across the country—ninety men and thirteen women—met and resolved that the mission of the new ALA would be “to enable librarians to do their present work more easily and at less expense.” Despite the rapid growth of women in the library profession, the ALA would not elect its first woman president, Theresa Elmendorf, until 1911.

In 1904, librarian Mary Cutler Fairchild would note that participation by women in American Library Association meetings was disproportionate to their attendance. Her research indicated that in libraries, women greatly outnumbered men, holding a large proportion of administrative positions but with little administrative responsibility. In addition, women did not hold positions offering the highest salaries, but rather appeared to perform the same level of work for less compensation.

Library Schools

As the stewardship of libraries grew from an elite pastime into a profession for men and women of more diverse backgrounds, librarians quickly developed educational standards for professionalization. These standards were taught through training programs at a growing number of library schools. The first library school was Columbia University’s School of Library Science which was founded in 1887 by Melvil Dewey, the creator of the Dewey Decimal System. The program left Columbia two years later with Dewey to spend the next thirty-seven years in Albany as the New York State Library School.

Like libraries themselves, library schools were often directed by men but operationally run by women faculty members who taught the majority of classes. Many programs were run not out of colleges, but out of working libraries staffed by women. This model allowed librarians to share their professional experience through courses on core services like cataloging, collection development, reference, and children’s librarianship, as well as a growing number of new fields.

At the turn of the twentieth century, library education was seen as a good career path for primarily white, middle- and working-class women who could either not afford or did not want to go to college. It also attracted women as a second career when teaching was not a good fit. Some women continued their education after college with library school because it offered them a more focused and usable curriculum. Among the career paths available to women at this time, librarianship appealed to many because the training was relatively short, the career path offered public service and, as the nation expanded westward, potential opportunities for adventure.

Professionals

As a constellation of libraries rapidly spread across the US at the turn of the twentieth century, a corps of passionate, trained librarians stepped up to staff them. Library jobs in the eastern, more populated areas of the country became highly competitive, and many women librarians were compelled to move to rural southern and remote western destinations in order to put their educations to work. Many assumed leadership positions in their new libraries because of their unique knowledge and skills.

These new jobs came with difficult contexts and challenges. In remote places, new librarians often arrived to find that residents prized libraries more as meeting places than educational resources. Communities rarely used the outdated or unappealing materials they offered and provided limited or no financial resources to revise their collections and programming.

Despite these obstacles, successful librarians transformed their libraries into cultural centers at the heart of their towns. Many created traveling libraries to reach rural areas. Others worked in collaboration with schools to create programming for children that might also attract parents, or programs that brought educational materials to the workplace. Far from embodying the stereotypical image of the shushing, uptight spinster, this generation of independent women librarians innovated ways to provide access to information with few resources and performed tasks, like horseback book delivery, that were considered men’s work. Despite the dangers and isolation of remote settings and the close watch of small communities, women librarians in the west and rural south were often afforded unique freedoms and treated as valued members of the community. These librarians were also supported by a new generation of middle and working class women volunteers who helped bridge the staffing gaps and make library services available to broader audiences.

Pioneers

Among the countless professional women who have worked in America’s libraries to serve their patrons, a number of women librarians were also pioneers who made major contributions to librarianship and stood up for women’s rights within the profession. Here are just a few of their stories.

Adelaide Hasse (1868-1953) was the originator of the system for classifying government documents, and a tireless advocate for higher wages for women and women’s suffrage. Her conflicts with male supervisors and New York Public Library’s male board of trustees would eventually cost her her job.

Tessa Kelso was the controversial Los Angeles City Librarian, who, from 1889 to 1895, transformed Los Angeles Public Library using methods considered radical in their moment. She abolished membership fees, agitated for open stacks, and established the first systematic training of any type for library employees.

In 1948, African American activist and librarian Jean Blackwell Hutson was appointed acting curator of the Division of Negro Literature, History, and Prints at the 135th Street/Countee Cullen branch of NYPL. Over the next thirty-two years, Hutson would lead the growth of the collection and the development of the Schomburg Collection for Research in Black Culture—now an international research institution and a leader in its field.

Mary Wright Plummer helped found and then directed the Pratt Institute Library School, a progressive alternative to elitism in turn-of-the-century library education. Along with her colleague Josephine Rathbone, she pioneered education for children’s librarians. Elected in 1915, Plummer also served as the second female president of the American Library Association.

Carnegie Libraries

Overview

By 1920—less than 150 years after Benjamin Franklin first donated what would become a town’s first public library collection—there were more than 3,500 public libraries in the United States. This rapid expansion of the US public library can be traced back to another American man’s donation—steel magnate Andrew Carnegie. Carnegie’s funding had built about half of these 3,500 public libraries, earning him the nickname, the “Patron Saint of Libraries.”

Carnegie funded the building of 2,509 “Carnegie Libraries” worldwide between 1883 and 1929. Of those, 1,795 were in the United States: 1,687 public libraries and 108 academic. Others were built throughout Europe, South Africa, Barbados, Australia, and New Zealand. The last Carnegie Library grant in the US was issued in 1919.

Andrew Carnegie

Steel magnate Andrew Carnegie became one of the wealthiest industrialists in America but gave much of his fortune away for the “improvement of mankind.” When asked about the best philanthropic gift he could give to a community, his answer was a free library.

Carnegie, who was born in Scotland and moved with his family to Pittsburgh at thirteen years old, grew up in poverty. A turning point for young Carnegie, which would help guide his work as a philanthropist years later, was spending Saturday afternoons at a local private library at the invitation of a wealthy Pittsburgh man.

Carnegie eventually became superintendent of the city’s division of the Pennsylvania Railroad, but quit after seeing new opportunities in the iron industry after the Civil War. It proved a risk that paid off in a big way. Carnegie’s Keystone Bridge Company (which worked to replace wooden bridges with iron ones), his later Carnegie Steel Company, and investments in the United States Steel Corporation, made Carnegie a fortune as a steel tycoon. But some of his big business choices had dire consequences for working-class Americans—like the Homestead Strike and the Johnstown Flood—that tarnished his reputation and then fueled his desire to rehabilitate it through philanthropy.

In his autobiography, Carnegie remembered that, as a child, “I resolved, if wealth ever came to me, that it should be used to establish free libraries.” And he did, providing public libraries to communities across the country, all engraved, at his request, with an image of a rising sun and “Let there be light.”

Funding Carnegie Libraries

The first Carnegie library was built in Andrew Carnegie’s hometown of Dunfermline, Scotland. It opened to the public in 1883 with Carnegie’s “Let there be light” motto carved into the building’s sandstone entrance. It was the first in a series of Carnegie libraries built in places where he had a personal connection: first in his birthplace, and the next several in Pittsburgh, where he built his fortune. The first Carnegie library to open in the United States, for example, opened a few miles from Pittsburgh in Braddock—a town that was home to a mill for Carnegie’s Steel Company. Ultimately, nine of the first thirteen commissioned Carnegie libraries were built in the Pittsburgh area.

After 1898, thanks in part to women’s groups nationwide organizing to establish community libraries, Carnegie began expanding his efforts across the country. Towns began sending requests for funding to Carnegie, citing everything from the need for a way to counteract the influence of the town’s saloons, to the need for a Carnegie library because a rival town had one. Funding was in extremely high demand, as few public libraries had dedicated spaces of their own. Carnegie began to use a formula to determine which of the many requests he would fund. Rather than endowing libraries, Carnegie required each town to contribute ten percent of the annual funding to its library, supply its own building site, and provide free service to the public.

In addition to public libraries, Carnegie also helped fund university library spaces, as well as separate public libraries for African American patrons in places throughout the United States where segregation laws barred them from using other public library spaces.

Legacy

By the 1990s, nearly all of the 1,795 Carnegie-funded library buildings in the US were still standing. More than half were still being used as libraries, some with the spaces intact, others with new additions and expansions added to the original building, but all still serving the public in the same manner that Carnegie envisioned. Some of the other Carnegie buildings had been converted for other public purposes like community centers or museums.

The impact of Carnegie’s funding on the US library system is far-reaching even now, over one hundred years since the first Carnegie library opened to the public. These libraries remain central branches in cities like New York and Pittsburgh (who named their public library system as a whole after Carnegie). In particular, they helped often underserved, lower income communities connect with important public services.

Carnegie’s libraries have made an impact on a personal level, too. Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas wrote in his memoir about going to the local Carnegie Library in Savannah, Georgia, as a boy, and studying there as a young man. That particular Carnegie Library, founded by the local Colored Library Association, opened in 1914, giving African American patrons a place they could access books decades before the library system integrated in 1963. When the original library re-opened in 2004 (refurbished after it closed in 1997), Thomas was the keynote speaker and recalled that, for him, the Carnegie librarians “made it all possible.”

Community Services

Branching Out

In the nineteenth century, local governments and philanthropists built public libraries centrally in cities, counties, and towns across the country, giving Americans previously unprecedented access to books and other educational materials. As this movement gained momentum, central libraries started thinking critically about how to best serve geographically broader communities. Beginning in the late 1890s, central libraries opened smaller branches in cities to accommodate the explosion of urban population growth. As immigrants set up their own communities away from the more expensive city centers, new branch libraries helped provide services to these new enclaves.

These branch libraries made it possible for patrons to access library collections and services without needing to use public transportation, removing barriers to access like time and cost. Moreover, they brought programming and accessible meeting places to new parts of their growing urban constituency.

The expansion of the branch libraries boomed again in 1962 with the Library Services and Construction Act, which helped fund new library spaces for underserved communities. Now, there are more than 7,500 branch libraries in the United States—almost as many as central public library buildings—providing critical services and collections to patrons.

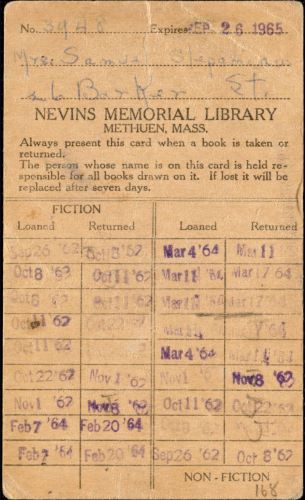

Collections

At the core of the public library’s mission is community access to its collections. As such, cataloging, acquisitions, and lending are important parts of library operations. Shared cataloging has existed since 1901, when the Library of Congress produced its first printed catalog cards. Cataloging items is key in helping patrons access and check out materials. Beyond cataloging, and acquiring new material, collections can also be shared between libraries via interlibrary loan, standardized by the American Library Association in 1952.

Early in the history of public libraries, however, providing access was at odds with some libraries’ complicity in censoring books in their collections. Although school libraries were the most active in promoting “morally acceptable” reading through book censorship, some public libraries played a role, too. For example, the Kern County Free Library in California complied with a county-wide ban against The Grapes of Wrath that lasted from 1939 to 1941.

By the 1950s, the ALA began taking an anti-censorship stance. The “Freedom to Read” statement, supported by the ALA and other booksellers’ and publishers’ associations, was adopted in 1953. Now, public libraries play an active role in collecting and supporting the reading of banned books. The ALA, for example, is a participant in Banned Books Week which highlights commonly contested books such as Catcher in the Rye and The Bluest Eye.

Though library collections have traditionally included books and periodicals, they have also grown to include so much more. Libraries have not only adapted to, but embraced new technologies. Even before the rapid changes brought on by the computer age, libraries integrated things like microfilm and taped recordings into their collections.

Reference

Beginning in the early 1900s, public libraries began transitioning from closed to open stacks. Under the pioneering example of Denver Public Library director John Cotton Dana in the 1890s, libraries shifted their physical design from housing materials in spaces accessible to only librarians, to giving patrons direct access to collections. Public libraries nationwide adopted this new approach to open stacks more quickly than their academic library contemporaries. As a result of this transition, the role of the reference librarian changed from gatekeeper of materials to research supporter and facilitator. Reference librarians spent less time traveling to and from the stacks.

A reference librarian’s work with patrons includes helping answer research questions and finding materials that match their interests. Moreover, reference librarians can help patrons connect with a variety of resources in the collection beyond just books and periodicals, like scholarly journals and special collections material. They are also valuable to the research process as it progresses, helping patrons narrow or specify their topics and creating proper citations.

Reference librarians are also responsible for creating pathfinders, or research guides, to help get a search started on commonly sought-for topics. Rather than a deeper search that librarians can help patrons with one-on-one, these guides give an overview of helpful sources that can be the jumping-off point for a user’s independent research.

Libraries often have reference desks that patrons can contact in person, over the phone, or, today, online or via text message. As such, reference librarians are often the most direct point of access for patrons looking to make the best use of the public library.

Programming

A cornerstone of the American Library Association’s “Core Values of Librarianship” is its emphasis on social responsibility and libraries’ critical role of serving the public. Public libraries’ attention to programming, in the form of classes, discussion groups, and community events, helps put those goals into practice.

Though some libraries, like other public spaces in the United States, have historically supported racial segregation, services have generally been available for patrons across class and gender lines. Moreover, public libraries remain some of the only truly free public spaces where local residents can meet outside of home and work. Public libraries, in cities and small towns alike, offer collaborative space (and now, wireless Internet and computer access) that are close and accessible to the community.

With renewed focus in the 1950s, US public libraries began extending their core services to include community programming. Typically, these include educational programs, like summer reading groups for children and discussion groups for adults, as well as spaces to host external clubs and groups from the community. The twenty-first century saw programming include computer and other STEM skills-building activities, hosting of concerts, art exhibitions, and gaming, the development of maker spaces, and extensions of their lending services to tool, seed, and even prom dress libraries.

The emphasis on programmatic public service is also apparent in times of crisis, when libraries have worked to respond to the immediate needs of their communities. After the destruction of Hurricane Ike in 2008, Houston Public Library mobilized to offer emergency aid. The library helped patrons work on FEMA aid paperwork, served as a public access point for distribution of food and water, and offered childcare services and a safe space for families. During this time of need, the library worked to serve its community, and continued to do so weeks after other aid organizations left Houston.

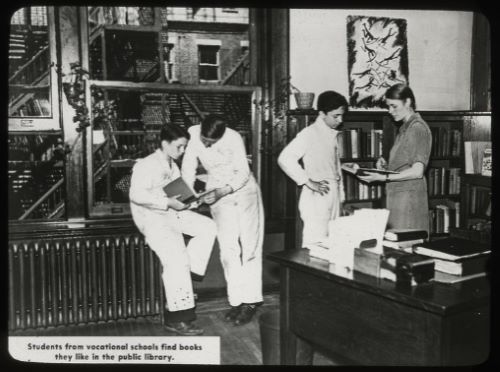

For Children

For the past century, libraries have focused on reaching the youngest members of the communities they serve—children. Starting in the late 1910s, the idea of developing library spaces in schools became a focus for educators, coinciding with a rise in literacy rates among young people. The movement for children’s libraries grew from libraries in schools to dedicated children’s materials at public libraries or new libraries especially for children.

Children’s librarians began organizing a professional community of practice with the Section for Library Work with Children organized in 1901 (later, the Children’s Library Association) and the Young People’s Reading Round Table, which met for the first time in 1930. These groups later merged with the American Association of School Librarians to form the American Library Association’s Division for Children and Young People in 1941. As the ALA restructured, the children’s focused group changed names, eventually organizing as the Association for Library Service to Children in 1977.

Providing resources for kids was more than just a professional focus, but a programmatic one, too. Libraries have integrated things like reading programs, story hours, and stocking books on local schools’ summer reading lists. While some early children’s reading rooms, particularly in urban areas, were seen as a source of shelter and structure for young people, with a regimented order similar to a schoolhouse, later spaces were designed to be more creative and relaxed. At the center of these new designs and programs was public librarians’ understanding that they played an important part in helping children access and appreciate reading and learning.

Libraries on the Move

Overview

As public libraries grew in communities across the United States, they focused on creating better and better access for patrons to library resources. This included new, innovative thinking about how access could be made easier for patrons and how libraries could better serve communities that were isolated from them physically.

Libraries, thinking more broadly about how to bring books directly to the people, developed new programs aimed at previously untapped audiences who might find it too difficult to visit library branches. These included on-site libraries for workers and their families in unique places like railroad cars and factories, as well as library services in hospitals and prisons. In programs funded by communities, as well as the Works Progress Administration, libraries were bringing books to the community by foot, boat, horseback, and the increasingly popular bookmobile. In times of national struggle, like the Great Depression and both World War I and World War II, libraries mobilized to fulfill their missions of public service.

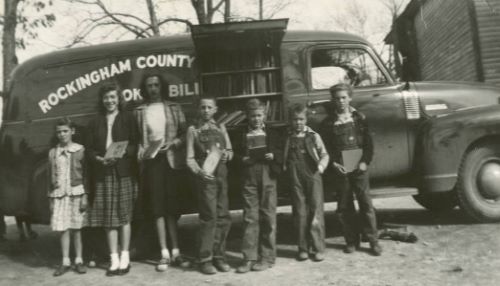

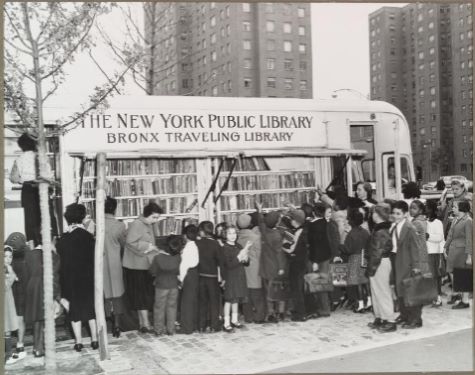

Bookmobiles

The first bookmobile in the United States took to the roads in the early 1900s. It was a horse-drawn carriage taking stacks of books to rural parts of Maryland. The librarian who started that program for the Washington County Free Library system, Mary Titcomb, described the bookmobile program’s success: “The book goes to the man, not waiting for the man to come to the book.”

Bookmobiles increasingly became a way for libraries to connect with patrons outside of the physical building, as vehicles brought books to seniors, schoolchildren, and most prevalently, families living in rural parts of the country. Community bookmobiles also brought library services to segregated communities throughout the south, as well as to schools on Native American reservations. For many of these isolated parts of the community, bookmobiles helped encourage access to literacy and connect families with books in a way never before possible. They began as a low-cost initiative for most libraries and spread throughout the early 1900s, but the Great Depression and World War II cut the growth of these programs and production of the bookmobiles themselves.

The Library Services Act of 1956, and its emphasis on rural library development, helped revive the bookmobile. Not only did the LSA help add more than five million books and materials to rural libraries, it put 200 new bookmobiles on the road. The combined effort meant that in many county and regional libraries, book circulation was up by more than forty percent.

WPA Library Programs

The Great Depression of the 1930s left millions of Americans and industries struggling. Libraries were no exception, with budgets slashed and former workers now facing unemployment. The public served by the libraries was suffering, too. At an American Library Association council meeting in May 1936, it was estimated that one-third of Americans were without “reasonable” public library access.

Enter the Works Progress Administration’s library projects, which served forty-five states, and employed approximately 14,500 people—some of whom were experienced librarians put back to work. These projects included assignments like book cataloging and repair, which helped save community libraries thousands of dollars. By February 1938, WPA-reconditioned books (including a project in Louisiana repairing books in braille for vision impaired readers), totaled close to thirty million.

The WPA also had a Library Extension program that funded and built about 200 new libraries, more than 3,400 new reading rooms, and 5,800 traveling libraries. These traveling libraries helped reach the most remote communities in America in unique—and often brave—new ways. In Mississippi, for example, a WPA librarian used a houseboat to distribute books to communities along the Yazoo River that were not connected to state highways. A successful packhorse librarian program in Kentucky employed over 200 workers and sent librarians on horseback to rural mountain communities. They travelled along creeks and cliffs, and sometimes part of the way by foot or rowboat. These packhorse librarians helped connect about 100,000 residents in remote parts of eastern Kentucky with reading material in a manner never before possible.

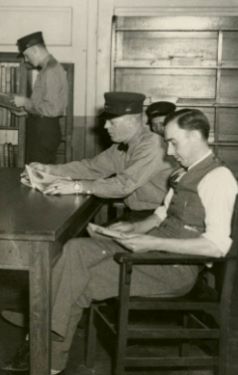

Wartime Book Campaigns

As World War I mobilized Americans in every sector to contribute to the war effort, the American Library Association and library branches nationwide began campaigns to help the country’s armed services. Only a few weeks into the war, the ALA began the “A book for every man” campaign, aimed at getting books into the hands of American soldiers. This campaign became part of the ALA’s Library War Services committee, established in 1917 and led by the Librarian of Congress Herbert Putnam.

Over the course of WWI, the ALA collected millions of dollars in donations, and ten million books and periodicals. Working alongside the Carnegie Corporation, they were able to set up thirty-six camp libraries, and get books to soldiers both abroad and at home. For the ALA, this was an opportunity to extend their service to Americans in a time of great need. As the War Services committee said in 1917: “If we succeed in this emergency in rendering national service, libraries are going to be a national and community force as never before.”

American libraries were called into service once again, twenty-five years later, during World War II’s Victory Book Campaign. During the campaign, the ALA (working with the Red Cross and USO) assembled seventeen million books and periodicals to send to American troops, with thousands of volunteers across the country sorting and shipping donations. The millions of donations were used to supply libraries in US military units, as well as USO clubs and libraries in war-torn Europe. The campaign was held at a time of considerable stress for libraries on the home front that were facing wartime funding and resource shortages.

Immigrants and Americanization

Overview

From 1880 to 1920, more than twenty million immigrants arrived in the US. Many traveled by steamboat at major ports and then set out via railroad for destinations across the country. Public libraries responded in specific ways to this massive influx of European immigrants, and, in certain parts of the country, to immigrants from Puerto Rico, Mexico, the Philippines, and Japan.

In response, public libraries amassed foreign-language collections that reflected the particular needs of the ethnic and national groups represented in their respective communities. Established in 1918, the American Library Association’s Committee on Work with the Foreign Born published a series of guidebooks for adapting collections to meet the needs of immigrants, starting with The Polish Immigrant and His Reading in 1924, followed by German, Greek, and Italian volumes. The emphases of these guides was on expanding collections to attract immigrants to libraries, supporting their reading interests, and giving librarians tips about serving people from other cultural backgrounds.

Public librarians in some places also made more holistic changes to library programming to engage recent immigrant arrivals. Beginning in the 1930s, Pura Belpré, New York City’s first Puerto Rican librarian, transformed the New York Public Library’s 115th Street branch into a vibrant community center for newly arrived Puerto Rican immigrants by purchasing Spanish-language books, instituting bilingual story hours, and offering programs on traditional holidays. With these innovations, Belpré modeled to other public libraries ways to serve the needs of Spanish-speaking patrons and advocated for the importance of their inclusion in public library strategy.

Americanization Movement

As a patriotic duty, the task of “Americanizing the immigrant” engaged a network of libraries, schools, churches, and other organizations. The Americanization movement, which began in response to both European immigration and World War I, reached its height around 1921, when more than thirty states and hundreds of cities adopted Americanization measures. Some of this legislation provided for positive support measures like night classes in English and civics at schools and libraries. Other legislation was more punitive, including prohibiting immigrants who had not been naturalized from holding particular jobs or the banning of foreign languages in public settings.

Public libraries were key partners in the Americanization movement. The Immigration Act of 1917, a response to increasing native-born anxiety about immigration, banned illiterate immigrants over the age of sixteen as well as most Asian immigrant entry into the US and would not be formally altered until 1952. Because of this legislation, public library Americanization activities included adult education trainings to prepare immigrants for citizenship and related literacy tests.

The American Library Association’s Committee on Work with the Foreign Born encouraged public libraries to incorporate programming that supported immigrant assimilation into American culture. In addition to helping immigrants with speaking, reading, and writing skills in English, programs helped them understand America’s history, participate in patriotic activities, and learn middle- and upper-class American cultural norms like rules for hosting guests and table manners. Some libraries that gave etiquette training to immigrant women also lent them place settings so that they might host dinner guests in the proper way even when they could not afford the equipment.

Adult Education Movement

Throughout the 1920s, librarians began to view the Americanization process increasingly as part of the newly identified adult education movement. This movement considered the needs not only of illiterate foreign-born immigrants but also of illiterate American-born adults. The once distinctly separate goals of American public libraries—to educate the general populace and to Americanize immigrants—were merging. Many public libraries understood their mission as building a literate citizenry composed of both foreign- and native-born Americans who were imbued with a spirit of patriotism.

The Adult Education Movement spread to public libraries through the committee and reporting work of the American Library Association. ALA promoted the creation of adult education programming in the form of literacy classes and discussion groups. Often, these groups offered discussion about patrons’ shared “American Heritage” and encouraged participants to understand present-day events, like the imagined communist threats during the Cold War, in the context of traditional American values like democracy. Adult education programming continued to include literacy offerings throughout the twentieth century and many public libraries still offer citizenship test preparation today.

Segregated Libraries

Overview

As public libraries spread across the United States at the turn of the twentieth century, state and local racial segregation laws were denying African Americans access to public facilities across the US South. In other regions of the country, state and local governments supported discriminatory labor and housing practices that, in concert with prevailing racist social ideas, restricted African American access to public spaces as well. In 1896, the Supreme Court upheld the “separate but equal” facilities as constitutional in Plessy vs. Ferguson, which justified the creation of segregated public spaces for African Americans, including schools and libraries, that were in practice inferior and underfunded compared to those available to whites.

As public facilities, the earliest public libraries in southern states excluded African Americans by law. When Andrew Carnegie funded the construction of a new public library in Atlanta in 1902, scholar and activist W. E. B. DuBois, then a professor at Atlanta University and a strong proponent of African American education, spoke out publicly against the injustice of a public facility that refused service to a full third of Atlanta’s population. The work of DuBois and other activists did not succeed in integrating public libraries, but it would bring funding for colored branches to the attention of philanthropists like Carnegie. In 1905, Louisville, Kentucky, would open the first free public library for African American readers staffed and operated entirely by African Americans. Atlanta’s first library branch for African Americans would not open until 1921.

Case Study: Atlanta

At the turn of the twentieth century, Atlanta was experiencing unprecedented growth of both its white and black populations as a result of the in-migration of rural southerners to growing urban centers. Atlanta was also home to a network of black colleges and universities as well as a thriving business district on Auburn Avenue. These factors contributed to an influential and well-educated black middle class, which shaped the city’s particular public library history.

Atlanta’s first public library branch for African Americans was the Auburn Branch, officially opened on July 25, 1921, in a red-brick building at 333 Auburn Avenue. From 1921 until the branch closed in 1959, numerous African American women librarians managed the branch and its educational and community programming. These included Annie L. McPheeters, who was responsible for the development of the special, non-circulating “Negro History Collection” and served Atlanta’s African American libraries from 1934 until her retirement in 1966. The Auburn Branch was a community center for African Americans located in the heart of its political and cultural district. Notable Atlantans, such as civic and political leader John Wesley Dobbs, frequented the branch, while the women who ran it represented the library in civil and political matters outside its walls.

By the 1940s, increasing numbers of African Americans migrated to Atlanta’s west side. In response, the city built a second branch to serve blacks. On December 6, 1949, the West Hunter Branch opened on the corner of West Hunter Street and Morris Brown Drive. The Atlanta-Fulton Public Library System formally desegregated in 1959.

Southern Services for African Americans

Despite the successes of libraries for blacks in urban areas like Atlanta, the growth of public libraries that served African Americans across the US South was scattered and slow. Some of the first facilities for African Americans were school libraries in Memphis, Tennessee (1903), and Galveston, Texas (1904), that opened their doors to serve a broader public. Other early libraries, like those in Lexington, Kentucky, and Jacksonville, Florida (1905), opened as segregated reading rooms for blacks within white libraries. Still others provided minimal service to black communities via bookmobiles or a single day each week on which blacks could visit the local library while it was closed to white patrons. Of the free standing public libraries for blacks, only a very few, like Brevard Street Library in Charlotte, North Carolina, were autonomous. Services for African Americans remained completely absent in many areas in the early decades of the twentieth century.

A few important sources would help fund the creation of African American library services in the South: Andrew Carnegie’s funding for segregated branches and Works Progress Administration library projects to improve rural services. But by 1946, just under one-third of the public library systems in the US South reported some form of service to African Americans (188 of 597), making library service available to about 34.2 percent of the black populations of these states. Despite a lack of funds, materials, and often, autonomy, existing African American libraries provided vital reading content to their patrons and formed important community spaces for discussion and education.

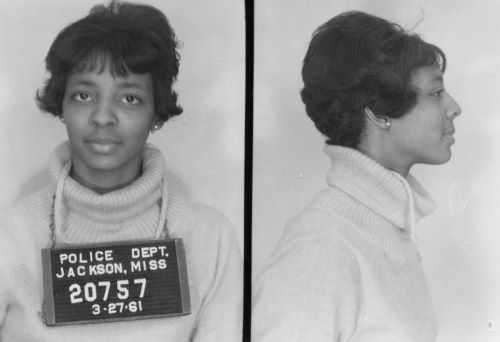

Desegregation

Although many activists challenged segregation laws through writings and individual action, it was not until the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s that segregated public libraries would be challenged through coordinated, non-violent protest action.

After careful planning, nine members of the local NAACP Youth Council (subsequently known as the Tougaloo Nine) attempted to use the white-only Jackson, Mississippi, public library on March 27, 1961. When they refused to leave, they were arrested and jailed for disturbing the peace. In 1962, similar student protests occurred at the local library as part of the Albany Movement in Albany, Georgia. In Anniston, Alabama, on September 15, 1963, two African American ministers were attacked by a white mob as they attempted to integrate the Anniston Public Library. These were just a few of the many sit-ins and protests that challenged the segregation of public libraries.

While some localities pursued integration more quickly, segregation laws would be dismantled on a national level by Supreme Court decisions and federal legislation. Three of these in particular would be important steps towards the desegregation of public libraries. In 1954’s Brown v. Board of Education, the US Supreme Court would overturn “separate but equal” in a ruling about segregated schools with broader implications. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 would specifically outlaw discrimination in public accommodations like public libraries. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 would give African Americans full access to the vote, which granted them power over local government and its public facilities.

Conclusion

Following from their first one hundred years of service, public libraries today thrive despite funding struggles. Once robust local funding for public libraries has been challenged over the past few decades, particularly in times of recession. Cuts leave institutions struggling to operate without necessary resources despite a consistent climate of public support.

Since their beginnings, public libraries have been at the forefront of adapting to and embracing new technology. The rise of the Internet and the prevalence of computers and mobile devices, however, has changed how libraries connect with their patrons. A crucial part of contemporary library services is access to the Internet, as well as free use of computer equipment. Public libraries also often subscribe to online research databases, which patrons can use. Other services like library websites, remote access catalogs, and ebooks have become central to the community’s library experiences. These services are supported by government projects like the Library Services and Technology Act and the Federal Communication Commission’s E-rate program as well as philanthropic funding from organizations like the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation—a digital-age equivalent to Andrew Carnegie’s library grants. The Gates Foundation, through its first project as an organization, granted $50 million a year over twenty years to public libraries to fund Internet access and computer equipment.

Public libraries are also innovating new uses for their physical spaces. Diverging from the silent reading rooms of old, public libraries now include bustling collaborative workstations, maker spaces, cafes, and other places for patrons to gather and interact. Library leaders have transformed the buildings themselves, like Seattle Public Library’s Central Library redesign in 2004, to facilitate these new uses.

Resources

- “A History of the Bookmobile.” PBS. July 19, 2011. Accessed June 18, 2015. http://www.pbs.org/pov/biblioburro/bookmobile.php.

- “ALSC History.” Association for Library Service to Children. Accessed June 18, 2015. http://www.ala.org/alsc/aboutalsc/historyofalsc.

- Battles, David M. The History of Public Library Access for African Americans in the South: Or, Leaving Behind the Plow. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2009.

- Bobinski, George. “Carnegie Libraries: Their History and Impact on American Public Library Development.” ALA Bulletin 62, no. 11 (1968): 1361-367. Accessed June 18, 2015. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25698025.

- Garrison, Dee. Apostles of Culture: Public Librarian and American Society, 1876-1920. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1979.

- Jones, Jr., Plummer Alston. Still Struggling for Equality: Public Library Services with Minorities. Santa Barbara, CA: Libraries Unlimited, 2004.

- “The Library Company.” Ushistory.org. Accessed June 18, 2015. http://www.ushistory.org/franklin/philadelphia/library.htm.

- Wiegand, Wayne A. Main Street Public Library Community Places and Reading Spaces in the Rural Heartland, 1876-1956. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2011.

Published by the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA), September 2015, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.