By Mark Cartwright

Historian

Introduction

Renaissance architecture originated in Italy and superseded the medieval Gothic style over a period generally defined as 1400 to 1600 CE. Features of Renaissance buildings include the use of the classical orders and mathematically precise ratios of height and width combined with a desire for symmetry, proportion, and harmony. Columns, pediments, arches, niches, and domes are imaginatively used in buildings of all types. Masterpieces which influenced other buildings worldwide include St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, the Tempietto of Rome, and the dome of Florence’s cathedral. Another defining feature of Renaissance architecture is the proliferation of illustrated texts on the subject, which helped to spread ideas across Europe and even beyond. The Renaissance style was frequently mixed with local traditions in many countries and was eventually challenged by the richly decorative Baroque style from the 17th century CE onwards.

Renaissance architecture was an evolving movement that is, today, commonly divided into three phases:

- Early Renaissance (c. 1400 CE onwards), the first tentative reuse of classical ideas

- High Renaissance (c. 1500 CE), the full-blooded revival of classicism

- Mannerism (aka Late Renaissance, c. 1520-30 CE onwards) when architecture became much more decorative and the reuse of classical themes ever more inventive.

Historians rarely agree on exactly when these changes developed and much, too, depends on geography, both in terms of countries and individual cities.

Studying the Past

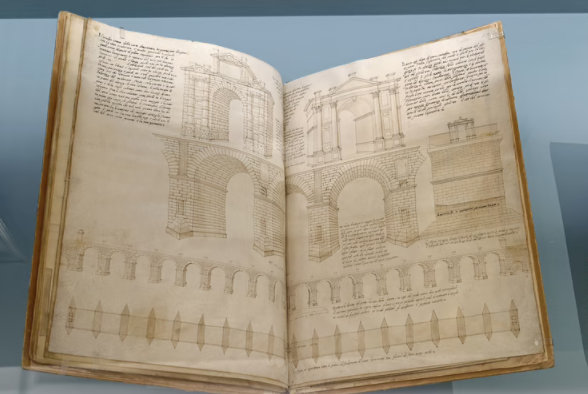

The Renaissance period witnessed a great revival in interest in antiquity in terms of thought, art, and architecture. The first and most obvious point of study for Renaissance architects was the mass of Greco-Roman ruins still seen in southern Europe, especially, of course, in Italy. Basilicas, Roman baths, aqueducts, amphitheatres, and temples were in various states of ruin but still visible. Some structures, like the Pantheon (c. 125 CE) in Rome, were exceedingly well-preserved. Architects studied these buildings, took measurements, and made detailed drawings of them. They also studied Byzantine buildings (notably domed churches), features of Romanesque architecture and medieval buildings. For many Italian architects, the Gothic style was regarded as an invasive ‘northern’ invention which ‘corrupted’ Italian traditions. In many ways, then, Renaissance architecture was a return to Italy’s roots, even if medieval architecture was never wholly abandoned.

A second point of study was surviving ancient texts, most particularly, On Architecture by the Roman architect Vitruvius (c. 90 – c. 20 BCE). Written between 30 and 20 BCE, the treatise combines the history of ancient architecture and engineering with the author’s personal experience and advice on the subject. The first printed editions came out in Rome in 1486 CE. Renaissance architects pored over this work, studied the emphasis on symmetry and mathematical ratios, and in many cases, even tried to build structures that Vitruvius had only described in words. Perhaps an even greater effect was that Vitruvius inspired many Renaissance architects to write their own treatises (see below).

Contemporary Influences

Architects not only studied the distant past but also what colleagues were doing elsewhere. Drawings and prints spread new concepts far and wide so that those unable to see new buildings in person could study developing trends. Sometimes, influences came from unlikely places. The Florentine painter and sculptor Michelangelo (1475-1564 CE) created some of the most famous of all Renaissance artworks, and these were hugely influential on later artistic styles. His bold and decorative reimagining of classical figures in art also influenced architects, encouraging them to try new ideas in mixing up classical elements and making them more decorative. Michelangelo was himself directly involved in architecture. His Laurentian Library, San Lorenzo, Florence (1525 CE) with its 46-metre (150 ft) long reading room, was a triumphal combination of aesthetics and function – two inseparable ideas for Renaissance architects.

Another influential artist-turned-architect was Raphael (1483-1520 CE). He similarly influenced architecture, in his case with the Palazzo Bronconio dell’Aquila in Rome (now destroyed). This building had a very rich exterior decoration and was a deliberate and novel mix-up of the conventional and functional arrangements of columns, niches, and pediments.

Even more influential than these artists, though, were the specialised architects whose buildings, treatises, and biographies spread their ideas across Italy and Europe. Filippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446 CE) is one such figure, and he is considered the father of Renaissance architecture. Brunelleschi was particularly interested in the study of linear perspective and achieving a harmonious simplicity of form in buildings which also considered the immediate environment in which they were constructed. Brunelleschi’s emphasis on classical proportions, simple geometry, and harmony were prime considerations in what became a new architectural language.

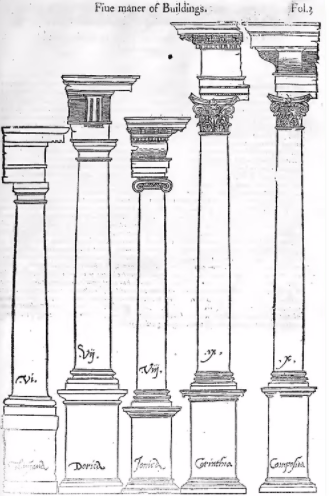

This architectural language was formally canonised by Sebastiano Serlio (1475-1554 CE) in his Seven Books on Architecture, a hugely influential theoretical and practical work (see below). Serlio formulated the five classical orders, the fifth having first been identified c. 1450 CE by the architect and scholar Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472 CE). These orders are: Tuscan, Doric, Ionic, Corinthian, and the fifth, Composite (a mix of Ionic and Corinthian elements). Architects would play around with these orders, mixing and reimagining them to create wholly unique buildings. Designers would also add to the mix other ideas such as clever effects of illusionary perspective, seen especially in the work of Donato Bramante (c. 1444-1514 CE), who was considered the founder of High Renaissance architecture. To better understand what each architect contributed to the movement that was Renaissance architecture, it is necessary to consider some of the key buildings of the period.

Churches

Churches continued to be a very important part of any community, and one of the most outstanding Renaissance contributions in this area was the dome of Florence’s Santa Maria del Fiore cathedral, designed and built by Brunelleschi. Completed in 1436 CE, the brick dome measures at the base 45.5 metres (149 ft) in diameter, and it made the cathedral the largest and tallest building in Europe at the time. The dome was a brilliant design and built without a fixed centring (temporary wooden scaffolding) during the construction stage. Rather, each circular course of the dome was completed before another course was added on top. The dome is self-supporting thanks to the 8 outer and 16 inner ribs that rise from the base to the peak and which create self-supporting arches. As a consequence of this system, the dome has a pointed profile and is composed of eight distinct sides. Another consideration for the architect was that a pointed dome gives much less side thrust on the drum below it than a hemispherical one, thus eliminating the need for extra support such as unsightly flying buttresses. Made from bricks laid in a reinforcing herringbone pattern, the dome is given further strength and lightness by having a double shell. Finally, it seemed the Renaissance had now surpassed the engineering feats of antiquity.

Churches were ubiquitous in Europe, but now many were given a facelift. The problem with such projects was how to match the symmetry of classical architecture with the medieval high-naved church. Alberti came up with one solution – to create a facade composed of three equal-sized squares (one on either side of the entrance and another above topped with a triangular pediment). The idea was put into reality for the facade of the Santa Maria Novella church in Florence (completed 1470 CE). The use of columns and pediment strongly remind of a Roman temple front. Alberti went even further with his facade for the San Andrea church (designed c. 1470 CE) of Mantua. Closely resembling a Roman triumphal arch, this was the first monumental classicizing building of the Renaissance. In addition, the interior repeats the arch theme with its massive piers and barrelled ceiling, the largest constructed since antiquity.

The Tempietto of San Pietro in Rome was designed by Bramante and completed c. 1510 CE. The building, located on what was considered the site of Saint Peter’s crucifixion, was the first Renaissance structure to use the complete Doric order from antiquity. The design, which blends classical and Christian ideas, is an excellent example of Renaissance humanism thinking expressed in architecture. The 16 classical columns (recovered from ancient buildings) are not only elegant and undecorated but the circle design of the temple was considered the perfect shape for a church as that was thought to be the noblest of geometrical forms. In addition, Christian buildings that commemorated martyrs were traditionally centrally-planned structures. The elegant facade and barrelled centre rising straight through a ring of columns to a soaring dome was imitated everywhere thereafter and can still be seen today in buildings worldwide, from London’s Saint Paul’s Cathedral to the United States Capitol.

In 1565 CE Andrea Palladio (1508-1580 CE) began work on the San Giorgio Maggiore church in Venice, a building inspired by the 4th-century CE Basilica of Maxentius in the Roman Forum in Rome. Like Alberti, Palladio sought to provide a classical face to an irregular medieval building behind. The facade, which has columns on massive bases topped by Corinthian capitals, is made up of two interlocking temple fronts. It was Palladio’s innovative solution to covering a sloping building with a symmetrical facade along classical lines. In 1576 CE, Palladio repeated the idea for the church now commonly known as Il Redentore (Christ the Redeemer), also in Venice. The interior is spacious with only a very wide nave and no aisles. It has very little decoration and is mostly white, Palladio preferring instead to give the church character by the play of the abundant light on his Corinthian columns and arches. The luminosity of the interior is largely thanks to semicircular windows filled with remarkably clear Venetian glass. Both of these Venetian churches contain elements seen in Roman baths such as multiple vaulted areas divided by screens of columns.

The culmination of all the aspects of Renaissance architectural features arrived with the new Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome. The old basilica, built on the site considered to be the tomb of Saint Peter, was demolished. Florence Cathedral’s record as the largest church in the world was about to be superseded. Many architects were involved in a project that dragged on for over a century, but the first major design input came from Bramante. Commissioned by Pope Julius II (r. 1503-1513 CE), the foundation stone was laid on 18 April 1506 CE. The final stone was laid in 1626 CE. The interior measures 180 x 135 metres (600 x 450 ft) while the magnificent dome has a diameter of 42 metres (137 ft) and rises to a height of 138 metres (452 ft) from ground level.

Public and Domestic Buildings

A public building which is often cited as a typical example of early Renaissance architecture is Brunelleschi’s Ospedale degli Innocenti in Florence (completed 1424 CE). The architect’s use of tall slim columns to support arches which create a loggia with shallow domes was imitated for the facades of many other types of public buildings throughout the 15th century CE.

In 1546 CE Palladio designed a new facade for the town hall of Vicenza (known thereafter as the Basilica Palladiana). The arches create what became known as the ‘Palladian window’, that is a pair of shorter double columns supporting the arch with each arch flanked by a single taller column. The idea contributed to what became known as the ‘Palladian movement’ in architecture, often called Palladianism.

In terms of domestic buildings, an influential reimagining of classical forms can be seen in Alberti’s c. 1450 CE Palazzo Rucellai in Florence. The flattened facade of pilaster columns and perfect symmetry even included a lower portion of diamond decoration, a direct reference to the ancient Roman wall-building technique known as opus reticulatum. This building was the first of the Renaissance to receive a facade using the classical orders.

Another significant contribution to new ideas in private buildings was made by Bramante with his 1501 CE Palazzo Caprini in Rome. It is known as the ‘House of Raphael’ after Raphael began living there from 1517 CE. It had an upper floor of classical orders and a lower rusticated floor of arched shop fronts. These two levels combined to create a strictly symmetrical facade, and it was hugely influential on palace buildings in Italy for the next two centuries.

Palladio was also hugely influential in domestic architecture. Working for wealthy landowners in and around Vicenza in northern Italy, Palladio designed many impressive villas which reimagined the temples of ancient Rome as private homes. He added a grand columned portico for the entrance (or even one for each side of the building), had a large central room topped by a dome, and put the whole structure on a raised platform. The best example is the Villa Valmarana, aka ‘La Rotonda’, near Vicenza, built c. 1551 CE. Later Renaissance architects would add terraced gardens to further enhance the visual experience of grand isolated domestic buildings.

As the 16th century CE wore on, Renaissance architecture evolved into the more decorative and inventive Mannerism. A good example of this change in mood is the courtyard of the Palazzo Marino in Milan (completed 1558 CE), designed by Galeazzo Alessi (1512-1572 CE). It is a theatrical presentation of classical elements almost obliterated by decorative sculpture. Compare this building with the classical symmetry and austerity of the High Renaissance Palazzo Farnese in Rome (design c. 1517 CE) by Antonio da Sangallo the Younger (c. 1483-1546 CE).

Finally, Renaissance architects were involved in less beautiful but practically useful projects such as building flood defences, fortifications, monumental public fountains, and town planning.

Written Works on Architecture

Many architects, as noted, wrote books on their subject. Alberti’s On Building (De Re Aedificatoria) came out in Latin in 1452 CE and then in the Tuscan vernacular in 1456 CE. Alberti catalogued the defining principles of classical architecture and noted how these might be applied to contemporary Renaissance buildings. He emphasised the need for buildings to be visible from all sides, that the designer should equally consider the interior and exterior, and they should be impressive both in size and appearance. The book became a sort of architect’s bible, even more so when it was printed in 1485 CE as Ten Books on Architecture. Justifiably, Alberti became known as the ‘Florentine Vitruvius’. Alberti’s work also began a wider discussion on the role of architecture in society, the relation of a building’s design to its function, and got people talking about architecture who were not directly involved in that field.

Serlio’s Seven Books on Architecture (1537 to 1575 CE) not only canonised the five classical orders as mentioned above but covered the surviving buildings from antiquity, contemporary architectural theory, and practical advice for architects based on models. A particular feature of these books is the inclusion of a great many detailed and accurate woodcut printed illustrations, often drawn by Serlio himself. Another influential and much-thumbed book on the orders came from Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola (1507-1573 CE), his 1562 CE On the Five Orders (Regole delle cinque ordini).

In 1556 CE Palladio provided a series of illustrations for a new edition of his hero Vitruvius’ On Architecture and then made his own contribution to the growing Renaissance library with his Four Books of Architecture (1570 CE). Immediately popular with architects, the work was translated into several other European languages, including four editions in English between 1663 and 1738 CE. The work considers materials, the classical orders, domestic and public buildings, and provides reconstructions of Roman temples. The books helped spread Palladio’s ideas on architecture because although they focussed on classical architecture, the author often used his own designs to illustrate the descriptions.

The Spread of Renaissance Ideas

Architects travelling to different cities and the spread of written works helped ensure Italy was not alone as a witness to the architectural revolution. Books were often translated and so, for example, the 50 illustrations of highly decorative doorways in Serlio’s books became popular with Mannerist architects in Northern Europe.

Architects also moved abroad. In 1541 CE, for example, Serlio left Italy for France, where he worked for the king, Francis I of France (r. 1515-1547 CE) on the design and construction of the Palace of Fontainebleau. Francis was a keen patron of the arts and had already employed Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519 CE) between 1517 and 1519 CE, possibly involving the Italian in the design for his massive new Chateau de Chambord. Serlio designed the Château d’Ancy-le-Franc (c. 1546 CE) with its classical-inspired facade of pilasters. This chateau is a typical example of how Renaissance ideas were blended with local architectural traditions across Europe in buildings of all kinds from Antwerp to Lisbon.

The English architect Inigo Jones (1573-1652 CE) famously collected original drawings by Palladio following a visit to Italy and so introduced his style to England. Jones designed such grand structures as the Queen’s House in Greenwich and the Banqueting House in Whitehall, London, both in the second decade of the 17th century CE. Palladio’s designs were also popular in Ireland and the American colonies where his columned entrance porches became a standard feature of everything from houses to libraries. Renaissance ideas even spread to other continents. The Spaniards travelled with architectural books and then copied elements into the buildings they erected in Mexico and Peru. Jesuit missionaries did the same in India and other parts of Asia. Meanwhile, back in Europe, the 17th century CE heralded a new architectural movement, which challenged the classically-dominated Renaissance style. This was the much more playful and exuberant Baroque style.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Christy. Renaissance Architecture. Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Campbell, Gordon. The Oxford Illustrated History of the Renaissance. Oxford University Press, 2019.

- Hale, J.R. (ed). The Thames and Hudson Dictionary of the Italian Renaissance. Thames & Hudson, 2020.

- Murray, Peter. The Architecture of the Italian Renaissance. Schocken Books, 1966.

- Rundle, David. The Hutchinson Encyclopedia of the Renaissance. Hodder Arnold, 2000.

- Summerson, John. The Classical Language of Architecture. Thames & Hudson, 1970.

Originally published by the Ancient History Encyclopedia, 11.23.2020, under a Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.