This study is useful for understanding the complexity of medieval bodies and gender.

By Sophie C-Sexon

Graduate Student in Theatre Studies

University of Glasgow

Introduction

This essay argues that Christ’s body can be read as a non-binary body in Late Medieval imagery through analysis of images of Christ’s wounds that appear in Books of Hours and prayer rolls. Wounds opened up the gendered representation of the holy body to incorporate aspects of femininity, masculinity and aspects that signify as neither. Through a reading of Christ’s wounds as potential markers of the genderqueer, I argue that an individual’s identification with the non-binary body of Christ could result in identification as a non-binary body for the viewing patron. Genderqueer interpretation of Christ’s body shows how non-binary visual interpretation more broadly is useful for understanding the complexity of medieval bodies and gender.

The Late Middle Ages in Europe saw a distinct shift in devotional practice from a collective to a more individual model of worship, encouraging more intimate relationships with the divine through meditative practices and the use of literary and artistic devotional aids. This period, understood as roughly 1320-1500 for the purposes of this chapter, manifested a change in Christ’s representation from a purely divine body to a body that simultaneously represented humanity and divinity. Empathy with the suffering of both the Virgin Mary and Christ was increasingly emphasized in worship and encouraged among worshippers. From the middle of the eleventh century onwards a new kind of affective piety encouraged devotees to contemplate Christ’s humanity and suffering as if it were their own.1 Affective piety encouraged intense reflection on Christ’s sufferings in the crucifixion and drew focus to Christ’s humanity and vulnerability. Thomas Bestul characterizes affective piety ‘by an ardent love for Christ in his human form, compassion for the sufferings of Christ, and intense longing for union with God’.2 Affective piety inspired devotion that entailed use of all of the senses, in order both to imagine oneself witnessing the Passion, and to viscerally feel and identify with Christ’s suffering. In particular, the image of Christ’s wounds opened up the gendered representation of the holy body to incorporate aspects of femininity, masculinity and aspects that signify as neither. This diversely gendered body could have personal resonances for every viewer by displaying bodily morphology recognizable to all, irrespective of their gender. Through a reading of Christ’s wounds as potential markers of the genderqueer, I argue that an individual’s identification with the non-binary body of Christ could result in identification as a non-binary body for oneself.

Non-binary is an umbrella term for a range of gender identities that signify neither as wholly female nor wholly male. Non-binary people may or may not identify as trans, since they reject their assigned sex/gender in favour of their identified gender.3 Although trans identities tend to be regarded as relatively recent, close attention to primary sources, including texts, images and objects, suggests that medieval people could – and did – have an awareness of their own gender as signifying outside the dichotomized binary of male and female, even without identifying language or discourses surrounding gender identity being present in the medieval period.4 Below, I offer case studies of devotional objects, specifically considering the function of prayer books and prayer rolls in which Christ’s wound(s) are depicted, to demonstrate that Christ’s body could be, and indeed was, presented as a body which does not conform to the binarized gender distinctions of male/female. In this way, I attend to the possibility that such representations may have had resonance for people in the medieval period who did not conform to the gender binary themselves, who could see their non-binary identities reflected in Christ’s holy body.

Studies of non-binary and genderqueer identities are recent phenomena; however, as Christina Richards, Walter Pierre Bouman and Meg-John Barker write, ‘it would be foolish to assume that non-binary gender is a purely modern phenomenon’.5 Here I use the terms ‘genderqueer’ and ‘non-binary’ synonymously to refer to people who identify neither as male nor as female, whilst acknowledging a wealth of complexity of identification within these terms.6 As Richards, Bouman, and Barker note:

In general, non-binary or genderqueer refers to people’s identity, rather than physicality at birth. […] Whatever their birth physicality, there are non-binary people who identify as a single sexed gender position other than male or female. There are those who have a fluid gender. There are those who have no gender. And there are those who disagree with the very idea of gender.7

This definition demonstrates that non-binary gender identification has less to do with the morphology of the body and more to do with the way an individual identifies, experiences and understands their own gender irrespective of their physicality. When making reference to visual sources depicting bodies there has to be, understandably, a considerable emphasis on morphology. However, I assert that a more diverse understanding of gender emerges that is appropriate to a medieval context if we consider these bodies in a different light. Rather than focusing solely on making binary distinctions and comparisons, richer and more complex understandings of the medieval body emerge when we practice a more fluid way of seeing the body in manuscript illumination not bound by the binary categories of ‘male’ and ‘female’.

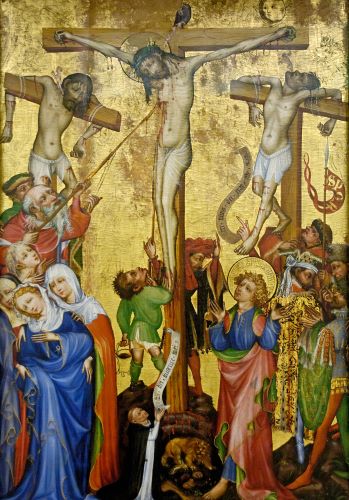

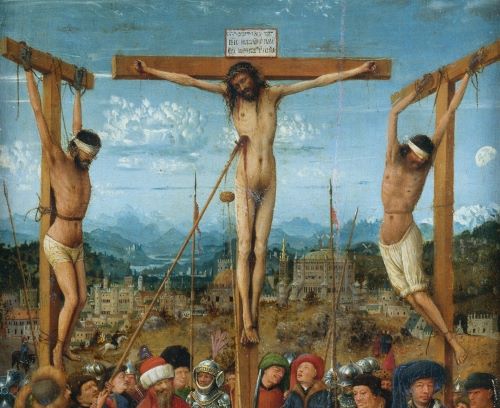

Gendering Christ’s Body: From Feminization to Fluidity

One did not need to identify as male to feel the pains and suffering of Christ, nor did one need to identify as female to feel the sorrow and grief of the Virgin Mary.8 Images and texts with intense devotional focus on Christ’s humanity proliferated in the Late Middle Ages, with the suffering body being depicted explicitly in a range of objects both public (such as altarpieces and wall paintings) and private (such as printed woodcuts and small ivories).9 However, artistic depiction of Christ’s gender necessitated greater fluidity in order to have productive relevance for women who were using this body as a personal devotional focus during affective meditation. As part of this change, depictions of Jesus as a mother f igure increased in popularity from the twelfth-century onward, particularly in the work of female mystics.

Since the 1980s, much attention has been paid to the feminization of Christ’s body in late medieval contexts by scholars including Caroline Walker Bynum and Karma Lochrie.10 Bynum’s work Jesus as Mother, for example, interrogates twelfth- and thirteenth-century writing to provide a history of spirituality amongst men and women of the era that was grounded in images of Christ’s holy maternity. She identifies common tropes, such as Christ feeding the individual soul with blood from his side wound as a mother feeds an infant with breastmilk.11 Where Bynum argues that Christ’s feminization is linked to maternal functions of feeding and nurturing, Karma Lochrie develops the arguments to include queer sexuality as a central aspect of Christ’s genderfluidity. In the article ‘Mystical Acts, Queer Tendencies’, Lochrie challenges and disrupts heteronormative historicist assumptions by engaging in a queer reading of mystical texts and manuscript images. She acknowledges the lack of organising terminology around discourses of sex and gender in medieval texts but speaks of sexuality to unsettle heterosexual bias in scholarship and to explore itinerant queer meanings and interpretations of texts and imagery concerning the feminized Christ. I propose to extend and nuance these analyses by looking at the feminization of Christ’s body not as a restructuring that renders the body wholly female, but as an aspect of Christ’s gender identity that lies between the bounded categories of male and female.

The marked feminization of Christ’s body in medieval art does not give way to a full morphological transition of Christ’s gender from male to female. Instead, both genders are incorporated into one holy body that signifies fluidly. Christ’s body is characterized, through a range of biblical stories and liturgical practices, as that which is subject to change. From transfiguration (a change of form from human to divine) to transubstantiation (a change from one substance [bread] into another [body]), Christ’s body is marked by impermanence, malleability, and an openness to representing contrary states in parallel. This can be seen in the hypostatic union of Christ’s divinity and humanity in one individual existence; Christ is both perfectly divine and perfectly human simultaneously. Conceptualizing Christ’s body as capable of expressing a range of genders, not limited to signifying in binary terms to a binarized audience, offers productive insights into medieval responses to the archetypically perfect Christian body.

Christ and various saints have often been depicted as being beyond binarized gender as an aspect of their holiness.12 Leah DeVun notes that in alchemical texts from the late medieval period Christ is often characterized as a hermaphrodite.13 Focusing on the early fifteenth-century Book of the Holy Trinity, a German alchemical treatise attributed to the Franciscan Frater Ulmannus, DeVun identifies ‘a new pair of images: the Jesus-Mary hermaphrodite and the Antichrist hermaphrodite.’14 The image of the Jesus-Mary hermaphrodite highlights the inseparable nature of Christ and Mary, which leads DeVun to describe Christ as ‘the ultimate hermaphrodite, a unity of contrary parts – the human and the divine, the male and the female’.15 DeVun notes that medieval saints’ lives also often reflect narratives where saints’ genders appear ambiguous or change, such as in accounts of Saints Pelagius of Antioch, Marinus and Wilgefortis; the former two saints were assigned female at birth but later changed their appearances and lived as men by choice, whereas the latter was given male secondary sex characteristics in response to prayer.16 In late medieval images of Wilgefortis, for instance, the bearded saint is depicted in imitatio Christi, crucified on a cross with one shoe off and one shoe on; the empty slipper playfully alludes to the vagina, as ‘an indication of the saint’s – and Christ’s – hermaphroditic nature.’17 These cultural and artistic artefacts align Christ’s body with these saints of undetermined gender, demonstrating how holy bodies can be seen to transcend binarized gender as part of God’s divine will.

Wellcome MS 632

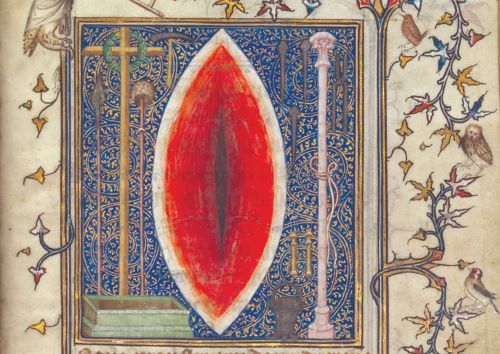

To show how the image of Christ’s wounds could be used to signify a break-down between binarized understandings of the medieval body, I begin by looking at the materiality of the image as used on birthing aids. Wellcome MS 632 is a parchment roll in worn condition, used as a birthing girdle in the late fifteenth century to protect women in labour.18 It contains images of the instruments of the Passion, the arma Christi; the crucifix; and Christ’s highly abstracted dripping side wound surrounded by Christ’s pierced – and penetrated – hands and feet. The inscription on the back states that the roll’s length is equal to the height of the Virgin Mary, and on the front, where there was intended to be an image of a cross, is the inscription: ‘If multiplied fifteen times, this cross is the true length of our Lord.’19 Therefore the scroll itself as a material object was positioned as an authentic measure of both the Virgin Mary’s feminine body and Christ’s masculine body, showing how both bodies could be tangibly realized via one object. The roll promises to protect both male and female users from sudden death, pestilence, death in battle, wrongful judgement and robbery, if the user bears the measure about their person and says certain prayers. It had a particular function for women in childbirth, who were to be granted a safe delivery, with the promise that the user would survive to be purified in church, and her child would survive to be baptized. This kind of birthing girdle was designed to be placed around the abdomen of the woman in labour. The physical juxtaposition thus makes apparent the link between Christ’s wound and the vagina, as the image of Christ’s bleeding wound resembles the body of the woman in labour.

Wellcome MS 632 is an example of the many kinds of objects that bore Christ’s wound, and that were intended to be used in childbirth.20 Use of these objects involved a tactile interaction with the image, in which women’s bodies came into contact with an authenticating measure of the body of Christ. These two bodies touched not only for protective purposes, but also in the manner that the female user of the object was assimilated to Christ: the body in childbirth mimicked Jesus’s suffering body in the Passion. In these tactile uses, the employment of the image of Christ’s wound destabilizes a binary understanding of Christ’s gender, demonstrating that Christ knows the pains of childbirth in his capacity as mother of the church.21 Therefore, the user of the material object comes to recognize Christ’s suffering as transcending gender, encouraging the idea that Christ’s identity is a non-binary one wherein labour pains can be felt through the side wound in an otherwise masculine-coded body.

Gendering Christ’s Wound(s)

Central to Christ’s apparent feminization is the prominence of his wounds, and the symbolic meanings ascribed to them. The iconographic isolation of Christ’s wounds as foci for contemplation is an important part of late medieval religious imagery, as the wounds display Christ’s capability for suffering and draw attention to his humanity. Of particular interest, both in medieval representations and in medievalist scholarship, is the side wound inflicted by the Roman soldier Longinus after the Crucifixion. This wound frequently appears, seemingly detached from Christ’s body, in Books of Hours, prayer rolls, and widely disseminated woodcut prints across Britain and Europe in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.22 Lucy Freeman Sandler notes that wound images start to appear after 1320, and that contemplation of the isolated wounds was characteristic of the fourteenth century, when narrative images were replaced by devotional ones to create greater emotional impact.23

The symbolic representation of the side wound, by its visual association with the vulva and the vagina, opens up Christ’s gender to non-binary interpretations. The wound is frequently depicted in a vertical orientation, abstracted from the body; this has been analysed as symbolically representational of the vulva by scholars such as Karma Lochrie, Martha Easton and Flora Lewis.24 Where these scholars have contended that the wound as a vulvar synecdoche entirely feminizes the body of Christ, I argue that the vulva-wound is better understood as evidence of the integral fluidity of Christ’s gender, being incorporated into a body that refuses to signify as either/or within binary terms. Parts of Christ’s body represent the typologically female body, showing that the feminine and the masculine are inseparably connected, and that both elements must necessarily exist within Christ’s body. The icon is therefore not reducible to either gender.

Wound images often appear with an encircling inscription stating that this is the ‘true measure’ of Christ’s wound, and that certain indulgences can be granted if the wound is touched, kissed or prayed to as instructed.25 Bynum notes that: ‘An enthusiasm for measurement and quantification was a new characteristic of fourteenth- and fifteenth-century culture […] If made to the dimensions supposedly given in a vision or brought from the Holy Land, an image of the wound was Christ’.26 Therefore these images held importance as supposedly authentic measurements of a holy body, with a representative verisimilitude to the wounds made in Christ’s flesh. These measurements made the wound seem more realistic given the specificity of their measurement, but they also increased the likelihood that the size given could be approximate to the size of the vulva. The wound’s resemblance to the vulva gave it iconographic versatility, as well as another range of protective and apotropaic functions.

Images of Christ’s side wound could be rolled up and tied to the body to prevent illness, danger in childbirth, or sudden death. The veneration of wound images had a medical function, linked to the promise of preventing pain; Bynum argues that the side wound is, in medieval culture, ‘explicitly connected with birthing, measuring, or the obtaining of indulgences.’27 These disembodied wound images were at times explicitly connected with typologically female anatomy. Not only did they resemble the vulva visually, they were used to prevent pains associated with the vagina. Birthing girdles often carried depictions of the side wound; these strips of vellum were pressed against women in labour to help ease the pain of childbirth. Depicted on the vellum could be a range of images relating to Christ’s Passion (such as the arma Christi). Prayers to a variety of saints and holy figures would also be inscribed on them, which would grant protection to both mother and baby during childbirth if recited. The images and incantations were not only intended for use in childbirth, but also to help with period pain and other issues related to menstruation. Easton, for example, describes an amulet that purports to have the measure of the wound of Christ, that will aid problematic menstruation if the user makes an entreaty to Longinus.28 There are multiple meanings of wound imagery, and multiple reasons why image-makers utilized the wound. In the same moment, it could signify variously to different audiences, inflected with an overlapping plurality of gendered interpretations.

The Trans Haptics of Christ’s Wound

Contact with Christ’s wound, both as image and as literal wound, is central to its devotional potency, and the ways in which it signifies genderfluidity. This includes both spiritual or meditational contact with the wound, and physical skin-to-skin intimacy, such as pressing the girdle to the abdomen or touching the image with one’s fingers. Easton and Lochrie have discussed the erotic significance of images of Christ’s wounds in late medieval culture, acknowledging that the wound often resembles a vulva in these various depictions, and that images of the side wound have often been venerated by rubbing or kissing the image, suggesting eroticized devotional practices.29 For Lochrie this marks out queer contact with Christ’s body, however, it is not only eroticism that is suggested by these physical contacts with the image of the wound. Another queer aspect of this contact is the manner in which physical touches of the image help one to orientate one’s own body and understanding of gender.

Jack Halberstam encourages a tactile and haptic understanding of the contemporary trans body, writing that: ‘The haptic offers one path around the conundrum of a binary visual plane (what is not male appears to be female, what is not female appears to be male.)’30 For Halberstam the haptic is important as it encourages a method of knowing that goes beyond the visual and that ‘names the way the mind grasps for meanings that elude it while still holding on to the partial knowledge available.’31 In going beyond language and the visual, the haptic is a mode of perception adept at resisting binaries and useful for a trans understanding of the body.

The haptic is the mode engaged when we consider the material technology of medieval objects depicting Christ’s wound. As Bynum notes, ‘even where representational, medieval depictions are sometimes more tactile than visual.’32 This aligns with medieval conceptions of optics. There is a fundamental collapse between the categories of subject and object in medieval optical theories, such as Roger Bacon’s theory of intromission and extromission, popular in the thirteenth century, wherein species (versions of the object) were either emitted from the viewer’s eye to touch the object, or emitted from the object to touch the viewer.33 Touch was therefore an integral part of sight.

In this context, Alicia Spencer-Hall presents a theory of ‘coresthesia’ to describe how one interacts with a medieval manuscript. Coresthesia requires responding to text and image with touches, in the sense that the body not only touches the material object, but is ‘touched affectively by the text’s content’ and this process of touches ‘are conjoined, non-hierarchical operations which shape the experience of a text.’34 The experience of the text in a haptic sense therefore affects the reader in diverse ways, and in the case of wound imagery, shapes the terrain of the bodies both of the holy figures depicted within, and of the readers themselves. Spencer-Hall notes the non-hierarchical relation of text to image, material, and context, and how this also affects the hierarchy of subject and object within the praxis of viewing, as ‘the aim of religious vision was to fuse entirely with one’s object, God Himself: touching and being touched in a single glance […]. This haptic interplay ultimately renders subject/object labels irrelevant.’35 In this formulation, one fuses not only with God, but also with Christ as part of the Trinitarian nature of God: a body that is human and divine, and also genderfluid. There is not only the collapse of the subject/object distinction, and the collapse of binary classification through haptic understanding. There is also the collapse of the distinction between past and present, where the trans/non-binary reader of the present comes into contact with the trans/non-binary viewer of the past, in what Spencer-Hall calls a ‘trans-chronological rendezvous’, facilitated by the traces left by earlier readers in manuscripts.36 To take forward trans studies in the middle ages will require sensitivity to these rendezvous and attentiveness to possibility. It is not the retroactive ascription of contemporary identity labels to those who lived in the past that brings us forward. Rather, I propose acts of affective listening with the body, allowing our bodies to become the site of trans-chronological trans and queer assembly, touching and being touched across time.

When we read a manuscript or view a medieval object, it is not only the text and illuminations within that command our attention. What bring us into dialogue with the viewer of the past are the marginal annotations, the dirt marks on the page, the smears of painted pigment rubbed off by lips and fingers, the ghostly remnants of objects that were pressed into the manuscript that have fallen out over time. The handled object is brought to life by haptic understanding, wherein the ways bodies have used it come to tell us something about how the images were viewed and understood. When reflecting on the haptic and material uses of objects such as birthing girdles and manuscripts we also come to know the non-binary body through handling objects depicting the body and thinking about the various ways touches help us to reflect on gender through use. However, manuscript images sometimes depict themselves how we should touch an image and, in doing so, teach us how to think about the bodies that we touch – both our own and those of others.

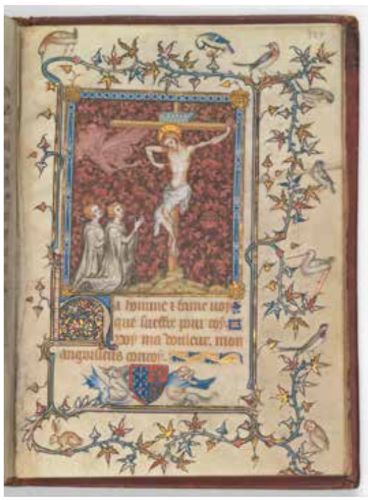

Bonne of Luxembourg’s Book of Hours

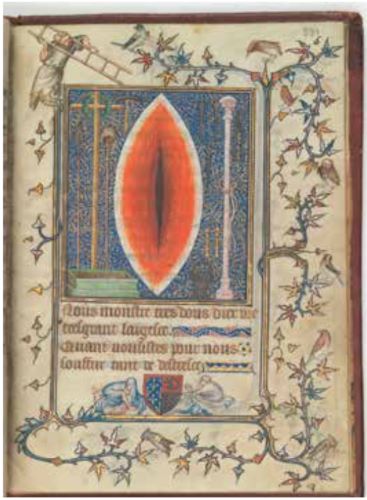

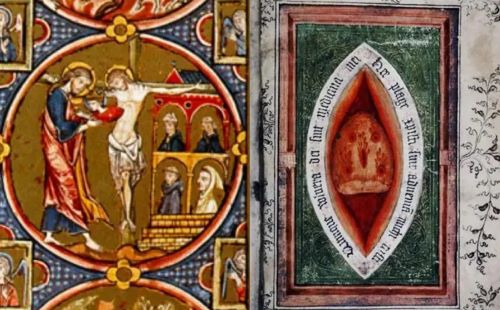

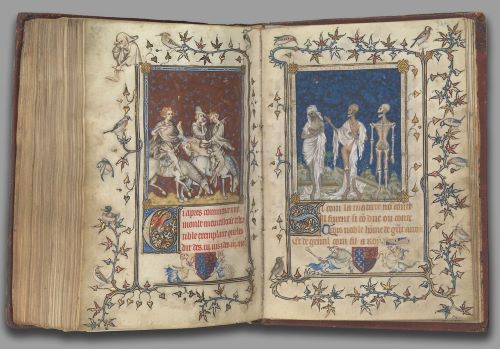

The way Christ’s side wound is depicted in manuscripts demonstrates the complexity of the trope. One such example can be seen in Bonne of Luxembourg’s Book of Hours (c. 1349), illuminated by Jean le Noir with grisaille miniatures.37 This relatively small prayer book, measuring 13.2 by 9.7 cm, was made for the Bohemian princess Bonne of Luxembourg (d. 1349), wife of John, Duke of Normandy. The small format of this manuscript, and other similar Books of Hours, indicates the intensely personal and private relationship that the owner-user was encouraged to have with the object. The images and text within are so small as to necessitate a considered and intimate focus during use.38 The narrative revealed by the succession of images in the book guides the user to think through the images carefully in conjunction in order to contemplate the wound fully, therefore incorporating the handling of the manuscript into the practice of devotion. Folio 328r (Fig. 1) depicts Bonne of Luxembourg and her husband kneeling before Christ on the cross, who draws focus to his side wound through gesture. With his elongated, phallic finger, Christ invites us to contemplate his wound by pointing at it and touching his finger to the wound.

Spencer-Hall focuses on the ‘agape-ic’ encounter in medieval hagiographic texts, staking the claim that ‘the scopic act can be an experience of complete mutuality between the individual who looks and that which is looked at.’39 This encounter is conjoined with transcendence, a glory that is felt in the viewer’s body: ‘This is due to the inherently synaesthetic nature of the scopic act, in which looking opens out into multisensory experience across the viewer’s entire body.’40 Felt with many of the senses, this feeling of ecstasy is also a transitory state. The agape-ic encounter shares in Halberstam’s notion of the haptic, as it brings one’s self into being, where looking becomes a form of feeling. It is described as an ‘act of genuinely reciprocal spectatorship’ as the object exerts itself as subject and returns to us a sense of ourselves as object. In looking back at us, ‘we perceive (feel and see) ourselves being seen, and thus we are looked and felt into being.’41 By confronting us directly, the presence of Christ’s fragmentary and divine body in Bonne’s Book of Hours is what causes us to consider our own body, and our own gender. The ref lection on this holy object is a reflection on ourselves as subjects, and brings us to awareness of the borders and boundaries where our own awareness of the gendered self breaks down. In Bonne’s prayer book we meet the gaze of Christ and are seen not only as the patrons of the manuscript in folio 328r (Fig. 1), but also as part of the body of Christ when we encounter the image on folio 331r (Fig. 2).

Turning the pages, the move from folio 328r to folio 331r expands and dilates the image of Christ’s wound. We progress from Christ on the Cross imploring the patrons of the manuscript to contemplate his wound, to a brightly coloured, elaborate image of the wound separated from Christ’s body and presented alone, surrounded by the arma Christi. The movement between folios zooms in on the side wound, enhanced by the image of the hybrid creature in the margins positioning a ladder above the border of the image, highlighting its significance to the viewer. The ladder is not only part of the arma Christi removed and abstracted from the central image, but is here used as a tool to convey some more information regarding the significance of the image gestured to. The ladder is a tool that links from the previous narrative image on folio 328r, indicating that we should ourselves climb it along with the hybrid creature from the margins of the image to contemplate the wound more specifically and fully that was depicted initially on 328r. This aligns the viewer with the hybrid creature from the margins as we share its tools for viewing the side wound, and encourages us to scrutinize more carefully those tools we use for interpretive visual functions. The hybrid creature is part human and part beast, and, as Robert Mills argues in the essay ‘Jesus as Monster’, Christ’s body too assimilates some of the hybridity of marginal figures.42 Christ’s body is structured by hybridity as our own is, and these manuscript images hint that this applicable to gender too by leading us to focus on the meaning of Christ’s abstracted vaginal wound.

The ladder not only directs us to contemplate the wound more fully, but Christ points to his own wound asking that attention be paid to it. In doing so, Christ invites the reader to think of the role of touch in their devotions. Christ extends an invitation to the person handling the manuscript to contemplate the wound through touch. Sight and touch are irrevocably bound when we view these images in conjunction with one another, and the subject/object boundaries are dissolved as outlined by medieval optics. The concepts of subject and object dissolve as we move from viewing the patrons of the manuscript on folio 328r to becoming the viewing patrons ourselves on folio 331r. We become not only the patrons, but also all of the affective participants in holy meditation who have chosen to focus so intently on the wound. Our position in viewing the wound on folio 331r also situates us as the touching finger of Christ from folio 328r, our entire bodies become a sense organ. Note also the change in the orientation of the wound from horizontal to vertical in the passage from folio 328r to 331r, which encourages vulvic connotations.

Touching the Wound

Tactile interaction with wound imagery is a tactic routinely utilized in devotional meditation, where touch becomes as important as sight.43 Mark Amsler writes that we see ‘the wound (vulna) as vagina (vulva), with a reading gesture at once sacred, erotic, scandalous, and transgressive.’44 This tactile understanding of wound imagery allows the reader to become one with the image, and to gain a more haptic understanding of Christ’s body as one that resembles one’s own, irrespective of gender. The reader identifies with Christ not only through imitatio Christi but also through viewing and recognising iconography that resembles their own body. The viewer is intended to have a personal and intimate connection with the images in the small prayer book, wherein one has the freedom to touch, to feel (literally and emotionally), to become, through meditative practices, similar to this suffering body, connected to it through touch and sight.

The Loftie prayer book, a mid-fifteenth-century Book of Hours written in Dutch, offers another example of such haptic engagements.45 With eighteen grisaille miniatures produced by the Masters of the Delft Grisailles, the Book is relatively small, measuring 9.5 cm wide by 14.5 cm high. Most of the illustrations within the book show no traces of tactile engagement, save for folio 110v, a miniature of the five wounds of Christ next to a Prayer to the Five Wounds of Christ. In this image, the lower two wounds have been touched or kissed in a way that has resulted in abrasion of the pigment.46 Since no other images have been rubbed away in this manuscript, it raises the question as to why the wounds have attracted such attention. Were these wounds touched with a feeling of identification, a sense of empathy, or even with erotic desire? Although there is no manner to identify the kinds of touches lavished upon the illustrations, we have the spectral remains of the adored image, and the knowledge that no other illustrations in the manuscript, including those of Christ’s body and face, have been touched quite so fervently. This singles the wounds out as objects of adoration in this particular manuscript, worthy of attention that other body parts do not merit.

The birthing girdle and the manuscript image, as objects to be touched, kissed and used with full acknowledgement of their materiality, engage affective piety and encourage the utilization of all the senses in order to convey a complex theological understanding of Christ’s body as that which is always similar to one’s own. The haptic is evoked when viewing images in which Christ’s finger points to his wound, asking the viewer to consider how that suffering body is similar to their own suffering body. The image erases the opposition between subject and object by pointing out the similarities between Christ’s humanity and the humanity of the viewer. The viewer is an affective participant in Christ’s suffering, and their body mirrors the icon irrespective of the gender of the viewing subject. Halberstam writes that hapticality is a form of knowing that exceeds the rational and intellectual, instead relying on the senses and feeling in much the same manner that late medieval affective piety encourages one to know the body of Christ. For Halberstam, ‘This is a perfect frame for the trans* body, which, in the end, does not seek to be seen and known but rather wishes to throw the organization of all bodies into doubt.’47 This frame also works well for the divine body of Christ which, in its fragmentary and multivalent state, throws the organization of all human bodies into doubt. The viewer is encouraged to use all of their senses in order to challenge their ways of knowing the fragmentary, trans/non-binary body of Christ, in order to understand a body which does not signify wholly as masculine or feminine, as it conveys a complex theological message about the roles Christ plays in Christian devotion. The manuscript images of gestures and touches, and the rubbed remains of images ardently kissed demonstrate that medieval viewers understood the body through using their senses to engage with images beyond sight alone.

The artistic depiction of Christ’s genitals has been a topic of wide scholarly and theological debate. Corine Schleif shows that Gospel accounts are ambiguous about whether Christ was stripped down to the skin and notes that this matter was the subject of debates in the thirteenth century and again around 1500.48 His nakedness during the Passion created a conundrum for medieval artists, as they dealt with an increase in demand for images of Christ’s Passion across the visual arts. The tension between depicting a suffering human body and a body that was divine had to be addressed with delicacy by image-makers. One aspect of Christ’s nudity to be considered in this context is the displacement of attention from the genitalia to the side wound in images of the Passion.

Wound imagery may have been used as an apt way to address ideas of humanity and generation within the Christ-icon. Christ would need to be depicted with male genitalia if he was to embody the ideal human form. However, to be depicted in this way would problematically ascribe a sexuality to the divine body. Drawing focus instead to Christ’s wound resolves the problem of depicting genitalia, as evidenced in the Man of Sorrows image on folio 19r of the Rothschild Canticles. Here Christ is depicted nude at the moment of the flagellation, but the illuminator has depicted Christ’s body twisted so that his left leg covers the genital area. Instead, focus is drawn to the side wound, encircled by red pigment, to which Christ points. Christ’s wound draws attention away from the genital area, while also representing genitalia. The phallic pointing finger suggests a penis, while the side wound suggests a vulva; both are present in one body, and in one image, just as in Bonne of Luxembourg’s Book of Hours.49 The wound as vulva renders Christ’s body generative – he gives birth to the church through the wound – without the need to display genitalia. The central depiction of Christ’s wound provides representation of female anatomy without fully feminizing Christ’s physical form. His body is then understood in parts: this feminized aspect of Christ is part of the whole, a union of the feminine and the masculine that allows both men and women to see themselves reflected in a body that signif ies in non-binary terms. The wound, as symbol, achieves this purpose by reflecting both Christ’s humanity and his divinity, his masculinity and his femininity, through synecdoche.

Physical objects carrying the image of Christ’s wound could thus be used to engage a complex, haptic understanding of Christ’s body as non-binary. The abstracted vulva-like wound asks how we come to gender ourselves when we focus on the elements of our bodies. As Bonne of Luxembourg’s book attests, we are not only the viewing patrons shown within the margins of folio 328r. We are also, ourselves, the body of Christ as shown on folio 331r, just as we are, too, the hybrid viewing creature in the margins of folio 331r; both human and animal in nature, capable of being both male and female, in the course of our affective meditations.

Representational images of Christ’s body assimilate aspects of culturally defined masculinity and femininity into one body. I argue that medieval audiences would have understood and accepted the fluidity and flexibility of Christ’s gender, particularly when reflecting on this body through affective practices such as imitatio Christi. By analysing a body so central to Western iconography I hope to open up the possibility for further non-binary readings of medieval imagery, both secular and sacred. Such readings help us to understand that the later Middle Ages had a refined view of gender not entirely dependent on the gender binary, and thus contribute to the project of identifying, defining, and exploring the history of non-binary identity.

This essay shows what a non-binary hermeneutics of medieval art history might look like in the attempt to acknowledge the ‘full ideological existence’ of transgender identities.50 As Robert Mills has previously stated, it is important to do this work to militate against the ‘phobic underbelly […] in which queer possibilities continue to be checked, censured and circumscribed in even the most purportedly ‘liberal’ contexts.’51 To take forward transgender studies of the medieval period will require sensitivity and attentiveness to possibility. Sensitivity entailing both a literal use of the senses, and a sensibility not commonly found in proscriptive academic discourse. We do not ask for the ascription of contemporary identity labels to those who lived in the past, as it is not for us to retroactively ascribe. When one reads a medieval text or glimpses a manuscript illumination that resonates with something in you, this is the material touching something in you that is timeless and immaterial about our trans identities. Listen to your body and feel those queer touches, in order to be able to translate the medieval trans past to a modern audience. These touches tell you that your experiences and identity have always existed in some form, whether we had the language to designate or describe it, or not. And know that, through these touches, you are not alone, both historically, and among the community of trans and non-binary academics who have contributed to bring together the volume that you presently hold within your hands.

Appendix

Endnotes

- On this shift, see: Beckwith, Christ’s Body, pp. 43-73; McNamer, Affective Meditation.

- Bestul, Texts of the Passion, p. 35.

- See ‘Assigned Sex; Assigned Gender’ (p. 287), ‘Identified Gender’ (p. 301), and ‘Non-Binary’ (p. 306) in the Appendix.

- Whittington, ‘Medieval’. For a survey of medieval trans studies, see: this volume’s ‘Introduction’, pp. 22-23.

- Richards, Bouman, and Barker, ‘Introduction’, p. 2.

- See ‘Genderqueer’ (p. 299) and ‘Non-Binary’ (p. 306) in the Appendix.

- ‘Introduction’, p. 5.

- On Marian devotion and gender, see Waller, Virgin Mary, pp. 29-107.

- For examples of such objects, see Bynum, Christian Materiality.

- Bynum, Jesus as Mother; Lochrie, ‘Mystical Acts’.

- For other examples of Christ’s feminization with a focus on Christ as a nurturing mother figure, see Bynum, Holy Feast.

- For a summary of scholarship on saints’ gender as beyond binaristic categories, see: Spencer-Hall, Medieval Saints, pp. 56-59.

- ‘The Jesus Hermaphrodite’, p. 209. ‘Hermaphrodite’ is a now antiquated term for individuals who would now be referred to as intersex. ‘Intersex’ is the modern term for a person whose biological characteristics do not fit neatly within cultural binary definitions of ‘male’ and ‘female’. Intersex individuals are (almost) always assigned a binary gender at birth, and in most of the world are still subjected to non-consensual surgical or hormonal treatment. See ‘Hermaphrodite’ (p. 300) and ‘Intersex’ (p. 302) in the Appendix.

- DeVun, ‘The Jesus Hermaphrodite’, p. 208.

- Ibid., p. 209.

- On AFAB saints, see Bychowski (pp. 245-65), Ogden (pp. 201-21) and Wright (pp. 155-76) in this volume.

- DeVun, ‘The Jesus Hermaphrodite’, p. 213.

- Bühler, ‘Prayers’, p. 274. For a transcript and description of the roll, see Moorat, Catalogue, pp. 491-93.

- Olsan (‘Wellcome MS. 632’) gives the original: ‘Thys crosse if mette [measured] xv [15] tymes ys the trewe length of oure Lord’.

- For more examples, see Bynum, Christian Materiality, pp. 197-200.

- Amsler, ‘Affective Literacy’, p. 98.

- For examples, see Areford, ‘The Passion Measured’.

- Sandler, ‘Jean Pucelle’, p. 85.

- Easton, ‘Wound’; Lewis, ‘Wound’; Lochrie, ‘Mystical Acts’.

- On such measurements, see Areford, ‘The Passion Measured’, pp. 211-38.

- Bynum, ‘Violent Imagery’, p. 20.

- Bynum, Christian Materiality, p. 200.

- Easton, ‘Wound’, pp. 408-09; Rudy, ‘Kissing Images’, p. 51.

- Easton, ‘Good for You?’, passim and especially pp. 4-5; Lochrie, ‘Mystical Acts’.

- Halberstam, Trans*, p. 90.

- Ibid.

- Bynum, Christian Materiality, p. 38.

- Spencer-Hall, Medieval Saints, pp. 107-18.

- Ibid., p. 143.

- Ibid., p. 118.

- Ibid., p. 142.

- For further discussion of this manuscript, see Bynum, Christian Materiality, pp. 197, 199-201; Easton, ‘Wound’; Lochrie, ‘Mystical Acts’, pp. 190-191; Sandler, ‘Jean Pucelle’, pp. 86, 92, 94.

- Clanchy, ‘Images’.

- Spencer-Hall, Medieval Saints, p. 15.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 16.

- Mills, ‘Jesus as Monster’.

- For examples, see: Rudy, ‘Kissing Images’, p. 4.

- Amsler, ‘Affective Literacy’, p. 98.

- For more information on the manuscript, see Marrow, Passion Iconography, p. 225 (8b).

- Rudy, ‘Kissing Images’, p. 56.

- Trans*, p. 90.

- Schleif, ‘Christ Bared’. On this topic, see also: Steinberg, Sexuality of Christ.

- For further interpretation of this image, see Mills, Suspended Animation, p. 192.

- Spencer-Hall and Gutt, ‘Introduction’ to this volume, p. 11.

Bibliography

- Amsler, Mark, ‘Affective Literacy: Gestures of Reading in the Later Middle Ages’, Essays in Medieval Studies 18.1 (2001), 83-110.

- Areford, David S., ‘The Passion Measured: A Late-Medieval Diagram of the Body of Christ’, in The Broken Body: Passion Devotion in Late-Medieval Culture, ed. by A. A. MacDonald, H. N. B. Ridderbos, and R. M. Schlusemann (Groningen: Egbert Forsten, 1998), pp. 211-38.

- Beckwith, Sarah, Christ’s Body: Identity, Culture and Society in Late Medieval Writings (New York: Routledge, 1993).

- Bestul, Thomas H., Texts of the Passion: Latin Devotional Literature and Medieval Society (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1996).

- Birthing girdle, London, Wellcome Collection, Wellcome MS 632.

- Bühler, Curt F., ‘Prayers and Charms in Certain Middle English Scrolls’, Speculum, 39.2 (April 1964), 270-278.

- Burgwinkle, William, and Cary Howie, Sanctity and Pornography in Medieval Culture: On the Verge (Manchester: Manchester University, 2010).

- Bynum, Caroline Walker, Christian Materiality: An Essay on Religion in Late Medieval Europe (New York: Zone, 2011).

- —, Holy Feast and Holy Fast: The Religious Significance of Food to Medieval Women (Berkeley: University of California, 1987).

- —, Jesus As Mother: Studies in The Spirituality of The High Middle Ages (Berkeley: University of California, 1982).

- —, ‘Violent Imagery in Late Medieval Piety’, Bulletin of the German Historical Institute, 30, (Spring 2002), 3-36.

- Clanchy, Michael, ‘Images of Ladies with Prayer Books: What Do They Signify?’ Studies in Church History, 38, (2004), pp. 106-122.

- DeVun, Leah, ‘The Jesus Hermaphrodite: Science and Sex Difference in Premodern Europe’, Journal of the History of Ideas 69.2 (2008), 193-218.

- Easton, Martha, ‘Was it Good for You Too? Medieval Erotic Art and its Audiences’, Different Visions: A Journal of New Perspectives on Medieval Art, 1 (2008), 1-30.

- —, ‘The Wound of Christ, the Mouth of Hell: Appropriations and Inversions of Female Anatomy in the Later Middle Ages’, in Tributes to Jonathan J. G. Alexander: Making and Meaning of Illuminated Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts, Art and Architecture, ed. by Susan L’Engle and Gerald B. Guest (Turnhout: Harvey Miller, 2006), pp. 395-414.

- Halberstam, Jack, Trans*: A Quick and Quirky Account of Gender Variability (Oakland : University of California, 2018).

- Lewis, Flora, ‘The Wound in Christ’s Side and the Instruments of the Passion: Gendered Experience and Response’, in Women and the Book: Assessing the Evidence, ed. by Jane H. M. Taylor and Lesley Smith (Toronto: University of Toronto, 1997), pp. 204-299.

- Lochrie, Karma, ‘Mystical Acts, Queer Tendencies’, in Constructing Medieval Sexuality, ed. by Karma Lochrie, Peggy McCracken, and James S. Schultz (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1997), pp. 180-200.

- The Loftie Hours, Baltimore, Walters Art Museum, Walters MS W.165. <http://thedigitalwalters.org/Data/WaltersManuscripts/html/W165/> [accessed 14 August 2020].

- Marrow, James H., Passion Iconography in Northern European Art of the Late Middle Ages and Early Renaissance: A Study of the Transformation of Sacred Metaphor into Descriptive Narrative (Kortrijk: Ars Neerlandica, 1979).

- McNamer, Sarah, Affective Meditation and the Invention of Medieval Compassion (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2010).

- Mills, Robert, ‘Ecce Homo’, in Gender and Holiness: Men, Women and Saints in Late Medieval Europe, ed. by Samantha J. E. Riches and Sarah Salih (London: Routledge, 2002), pp. 152-173.

- —, ‘Jesus as Monster’, in The Monstrous Middle Ages, ed. by Bettina Bildhauer and Robert Mills (Cardiff: University of Wales, 2003), pp. 28-54.

- —, Suspended Animation: Pain, Pleasure and Punishment in Medieval Culture (London: Reaktion, 2005).

- Moorat, Samuel A.J., Catalogue of Western Manuscripts on Medicine and Science in The Wellcome Historical Medical Library (London: Wellcome Historical Medical Library, 1962), pp. 491-493.

- Olsan, Lea, ‘Wellcome MS. 632: Heavenly Protection During Childbirth in Late Medieval England’, Wellcome Library Blog <http://blog.wellcomelibrary.org/2015/10/wellcome-ms-632-heavenly-protection-during-childbirth-in-late-medieval-england/> [accessed 1 December 2018].

- Psalter and Prayer Book of Bonne of Luxembourg, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Cloisters Collection, MS 69.86.

- Richards, Christina, Walter Pierre Bouman, and Meg-John Barker, ‘Introduction’, in Genderqueer and Non-Binary Genders, ed. by Christina Richards, Walter Pierre Bouman, and Meg-John Barker (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), pp. 1-8.

- Rothschild Canticles, New Haven, Yale University Library, Beinecke MS 404.

- Rudy, Kathryn M., ‘Kissing Images, Unfurling Rolls, Measuring Wounds, Sewing Badges and Carrying Talismans: Considering Some Harley Manuscripts through the Physical Rituals They Reveal’, Electronic British Library Journal (2 01 1), 1-56. <https://w w w.bl.uk/eblj/2011articles/pdf/ebljarticle52011.pdf> [accessed 14 August 2020].

- Sandler, Lucy Freeman, ‘Jean Pucelle and the Lost Miniatures of the Belleville Breviary’, The Art Bulletin, 66.1 (1984), 73-96.

- Schleif, Corine, ‘Christ Bared: Problems of Viewing and Problems of Exposing’, in The Meanings of Nudity in Medieval Art, ed. by Sherry C. M. Lindquist (Farnham: Ashgate, 2012), pp. 251-278.

- Spencer-Hall, Alicia, Medieval Saints and Modern Screens: Divine Visions as Cinematic Experience (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University, 2018).

- Steinberg, Leo, The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art and Modern Oblivion, 2nd edn., (London: University of Chicago, 1996).

- Waller, Gary, The Virgin Mary in Late Medieval and Early Modern English Literature and Popular Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University, 2011).

- Whittington, Karl, ‘Medieval’ in ‘Postposttranssexual: Terms for a 21st Century Transgender Studies’, TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly, 1-2 (2014), 125-29.

Chapter 5 (133-153) from Trans and Genderqueer Subjects in Medieval Hagiography, edited by Alicia Spencer-Hall and Blake Gutt (Amsterdam University Press, 04.06.2021), published by OAPEN under the terms of an Open Access license.