Coming from Babylon, the text follows the traits common to cuneiform herbals.

By Dr. M. Erica Couto-Ferreira

Post-Doc Independent Scholar, Assyriology

Universität Heidelberg

Abstract

This article offers, in the first place, an overview on women’s healthcare in relation to childbirth in ancient Mesopotamia, as an introduction that helps to evaluate the meaning of the 7th century Assur text BAM 248 within therapeutic cuneiform texts on childbirth. We proceed to analyse the variety of therapeutic approaches to childbirth present in BAM 248, which brings together various healing devices to help a woman give birth quickly and safely. We analyse the text in its entirety as an example of intersection between different medical approaches to childbirth, given the number of differences in the complexity of remedies, in the materia medica employed, in the methods of preparation and application, even in the technical knowledge required and also, most probably, in the social origin and/or use of the remedies in question.

Conceptualizing Women’s Healthcare in Ancient Mesopotamia: An Introduction

Texts dealing with complaints affecting women’s healthcare, especially in relation to childbirth, are found among the first written evidence of healing in ancient Mesopotamia. From the second half of the 3rd millennium on until the end of the 1st millennium BCE we find them attested in major archaeological sites. There are but few therapeutic examples outside the field of reproduction and genitalia-related diseases where women are specifically mentioned1.

Therapeutic texts make use of the generic term NA, LÚ/awīlu, amēlu “man” to describe pathologies, while the term munus/sinništu “woman” makes its appearance in those cases where ailments specifically related to female genital problems and procreation in a wide sense are involved. In learned cuneiform sources, therefore, reproduction is perceived as the realm where women are in need of particular care. That cuneiform texts lack any manifest theoretical imprint is a feature that has frequently been emphasized in academic literature, but even then, systemisation and theoretical considerations can be effectively expressed through other channels. Texts allow us to get a grasp on how the female body was envisioned in relation to its reproductive capacities in the long run. Going through the major female health problems treated in cuneiform texts, we can ascertain that they relate to the treatment of infertility, miscarriage, vaginal bleeding, indispositions during pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum.

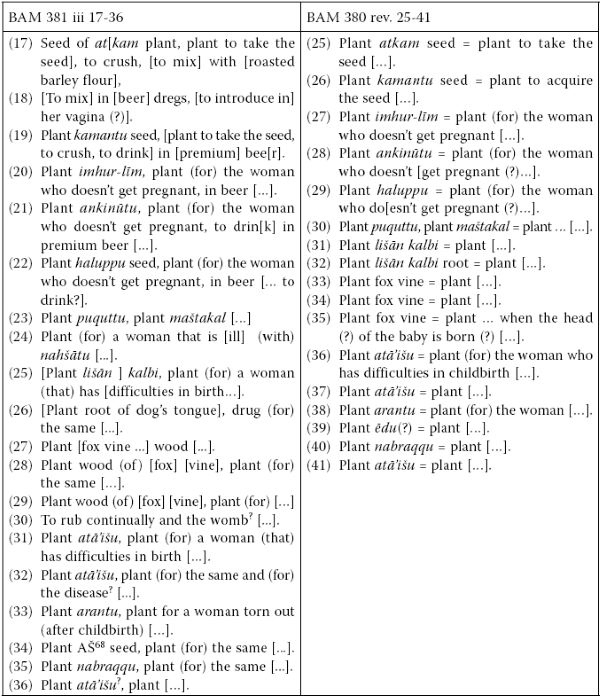

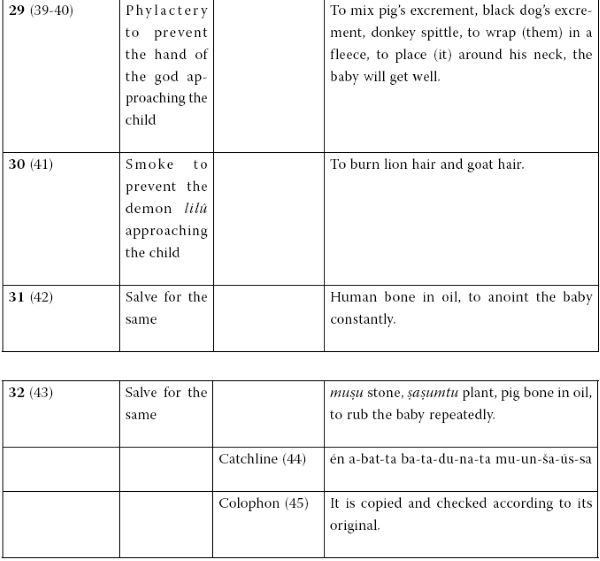

The section in the collection of remedies BAM 381 iii 17-362 show, together with its duplicate BAM 380: 25-41, this thematic pattern in an illuminating way (appendix 1). Coming from Babylon, this text follows the traits common to cuneiform herbals, namely: (a) the name of the plant; (b) the complaint it treats; and (c) preparation and application, with the contents being arranged according to (b)3. The section here transliterated and translated in Appendix 1 gathers a number of plants useful to treat female complaints, which are arranged following what was considered to be the female reproductive path and its main health dangers. It starts with plants for acquiring or taking the seed (atkam and kamantu plants); followed by materia medica to induce pregnancy (imhur-līm, ankinūtu, haluppu); to deal with problems during pregnancy (puquttu and maštakal in a treatment against nahšātu); to assist the mother in difficult labour (lišān kalbi, karān šēlibi, atā’išu); and, finally, to treat post-partum conditions (arantu, AŠ4 seed, nabraqqu, atā’išu? to treat šalputtu).

Both texts provide, therefore, an overview on: (a) those health conditions associated with women or that were considered specifically female in Mesopotamia, which, in this case, are clearly related to reproduction; (b) the phases of reproduction (taking the seed, pregnancy, giving birth, postpartum); (c) the most usual problems present in each phase of reproduction. However, it must be noted that other evidence from the cuneiform material deals with other kinds of ailments affecting women that, even when they closely relate to female anatomy, are not necessarily (or not explicitly) linked to the reproductive cycle. Within this context, text BAM 248 allows to explore historical issues linked to women’s healthcare, childbirth practices, and transmission of written medical knowledge in antiquity. BAM 248 not only demonstrates the variety of healing approaches and techniques available in ancient Mesopotamia to aid the labouring mother, but it also constitutes an enlightening example of learned ways of transmission and codification of knowledge converging under the sphere of the discipline of āšipūtu. This cuneiform tablet also challenges the issue of nature of medical knowledge the elites had access to, as well as calling into question previous considerations regarding which practitioners had access to the textual record, and how they put into practice the therapies reported in it.

(Difficult) Childbirth in Healing Cuneiform Sources

Overview

Pregnancy and childbirth have represented, until quite recent times, a danger for both mother and child in the Western world, and it is still so among many human groups and communities. The terror of pregnancy, as well as the consciousness of the dangers it involved, are also represented in different types of cuneiform sources. The physiognomic series “If a woman has a big head” (šumma sinništu qaqqada rabāt), for example, interprets the presence of certain physical traits in women as foretellers of death when pregnant or while giving birth5; while similar features, when present in the pregnant woman, can also portend a most tragic development of facts, as the diagnostic and prognostic series show6. Perhaps the most powerful accounts of the dangers of childbirth are found in these two examples we report here. The first fragment pertains to a Middle Assyrian incantation aiming at helping a woman in childbirth that depicts her as slowly approaching death:

“The (birthing) mother is surrounded by the dust(s) of death,

Like a chariot, she is surrounded by the dust(s) of battle,

Like a plough, she is surrounded by the dust(s) of woods,

Like a fighting warrior, she is fighting in her blood.

Weakened, her eyes don’t see, her lips are covered,

She doesn’t open (them) the fate of death and the fate of silence, her eyes (…)”7.

The second text we will touch upon refers to the “Elegy in memory of a woman”8. This Neo-Assyrian composition laments the premature death of a woman during childbirth through a rather heartbreaking language. Some of the images used, such as that which compares the dead woman to a wrecked ship (obv. 1-3), recalls a well-known trope of childbirth incantations, that is, that of the boat loaded with precious goods, which is equated with the mother in labour (or the foetus in the act of being born), that makes its way to the harbour. This device effectively brings into the discourse the echoes of a textual knowledge on childbirth which is used to express failure and final death through the image of the woman as a shipwreck:

“Why are you thrown in middle of the river like a boat?

Your boat’s beams broken; your ropes cut off;

Your face veiled, you cross the river of the Inner City?’

‘How could I not be thrown; how could my ropes not be cut off?

On the day I carried fruit, how happy I was!

Happy was I, happy my husband.

On the day of my labour pains, my face became dark.

On the day I gave birth, my eyes had an unhealthy appearance.

My hands (literally fists) were opened (in supplication), as I prayed to Bēlet-ilī:

You are the mother of those who give birth, save my life!

(…)

[Ever since] those days, (when) I was with my husband,

(as) I lived with him, who was my lover,

Death crept stealthily in my bed.

It brought me out of my home,

It separated me from my lover,

(And) set my feet toward a land from which I shall not return” (obv. 1-rev. 4-9).

Terminology

Turning to the references to difficult childbirth in therapeutic texts, we find a number of expressions that allude to it. Older texts tend to simply use the expression MUNUS Ù.TU.DA.KAM = sinništu ullad, sinništu (w)ālittu “(for) a woman (that) is giving birth”. On the other hand, MUNUS LA.RA.A(H.KAM)/mušapšiqtu9 “woman with difficulties in giving birth, woman in dire straits”, as well as the cognate šupšuqtu10, add the notion of a problematic childbirth. The root *pšq the Akkadian term mušapšiqtu derives from implies the notion, in fact, of narrowness.

An explanatory text from Nineveh comments upon the term MUNUS LA.RA.AH as follows:

[MUNUS LA.RA.AH] = MUNUS! ha-a-a-al-tú, […] = [MUN]US šá hi-lu-šá dan-nu “[woman with difficulties in giving birth], woman in childbirth, woman whose birth pangs are great”11.

However, other terms can also be employed. The wish for an easy unproblematic childbirth in therapeutic texts is expressed through forms such as arhiš Ù.TU (ullad) “she will give birth quickly” or the more generic SI.SÁ/ešēru “to go straight, to proceed well, to move forwards”12.

Rubrics in childbirth therapeutic texts usually bear, therefore, the titles ka-inim-ma munus ù-tu-da-kam “recitation for a woman giving birth”, KA.INIM.MA MUNUS LA.RA.A(H).KAM “recitation for a woman having a difficult childbirth”, KA.INIM.MA ÉN mušapšiqti (KUB IV 13: 13′) “recitation (of) incantation of a woman in dire straits”, and the like.

Difficult Childbirth and Therapy

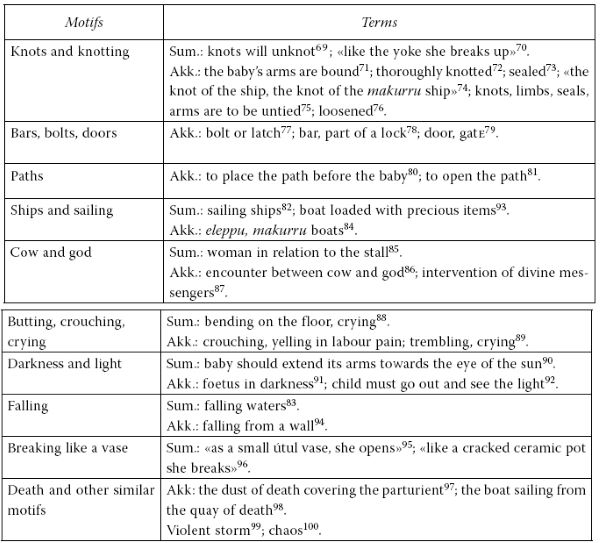

The critical moment of birth as well as difficult childbirth are represented in ritual texts and incantations through a number of tropes that tend to emphasize the state of the foetus within the mother’s body (appendix 2). In the oldest cuneiform evidences on childbirth, we already encounter the foetus pictured as being trapped, knotted, bonded, in fetters, or locked within a body whose door or bolt can’t be opened. The very act of giving birth, therefore, is expressed through performative utterances that emphasize the acts of unknotting knots, loosening the limbs, and breaking the seals that keep the child enclosed. Examples of this that predate BAM 248 are:

“He unties the knots

That have him (i.e. the baby) chained,

He prepares the road for him,

He opens the route for him”13.

“Gi-Sen, the servant of the god Sîn, she has a hard time (in) birth; the baby is stuck, the baby is stuck; in order to finish life, the bolt is fastened, the gate (is fastened?) against the suckling kid”14.

As we mentioned above when talking about the “Elegy in memory of a woman”, a boat burdened with a precious load that deploys its sails and navigates towards the “quay of life”15 recurrently appears in childbirth incantations. The boat may very well refer to the foetus that, still in its watery element, begins to move towards the birth canal. A different interpretation proposes that the boat would represent the birthing mother guiding her foetus, the precious load, through the waters of birth16.

Another frequent trope in childbirth incantations regards the historiola of the cow and the Moon-God, which describes the “antecedents”, namely the sexual encounter and impregnation that provides an origin to the present situation of childbirth. The Moon-God Sîn falls in love with a cow, he mounts her and she gets pregnant; as she experiences difficulties and pain in giving birth, the god Sîn sends two protective spirits to help her; she finally gives birth to a calf. The aim of the historiola is stated at the end of the incantation: as the cow of Sîn gave birth without further difficulties, so the woman in dire straits may give birth to her baby. Incantations of the cow of Sîn, or birth incantations containing references to cows and cattle pens, are already attested during the second millennium, not only within Mesopotamia17 but also in periphery areas such as Ugarit and Anatolia18, and even constitute the object of hermeneutical re-elaborations in late commentaries19.

These three tropes (opening of doors, sailing of boats, cow of Sîn) we find in second millennium evidences, together with some other images we have synthesized in Appendix 2, make their appearance in the healing procedures recorded in the tablet under analysis.

The Text BAM 248

Overview

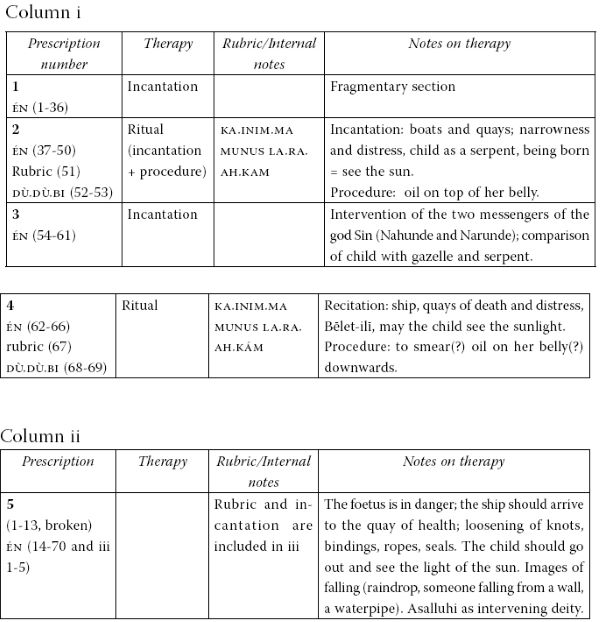

The text VAT 8869 (from now on, BAM 248)20 dates from the Neo-Assyrian period, more specifically from some point between the 8th and the 7th century BCE, and was excavated in the city of Assur, in the area commonly known as the “House of the incantation priest”21. It was found as part of a larger collection of tablets whose contents are mainly related to healing and ritual. BAM 248 exemplifies the persistence of written traditions and motifs regarding childbirth. This four-column tablet, whose obverse is badly damaged, gathers different treatments to help a woman with difficulties in giving birth. The text takes up older sources and motifs whose origin can be traced back to the Neo-Sumerian and Old Babylonian incantations and rituals. Even though it has been widely studied, translated and republished, this has been made mainly in relation to the incantations and ritual elements of the performance it contains, frequently leaving aside pharmacological prescriptions.

The relevance of this text derives from its comprehensive nature, since it gathers together different therapeutic approaches to ease childbirth, as well as a small final section containing remedies to protect the newborn child22 (appendix 3). Some of them were known from textual sources of the previous periods and show patterns of textual transmission; while others seem to have been added anew (how “new” this material is, however, remains to be seen). The result is a collection of very different medical techniques to deal with the same complaint. The contents are practical in nature, based on instructions to prepare or perform specific remedies and without including theoretical thoughts.

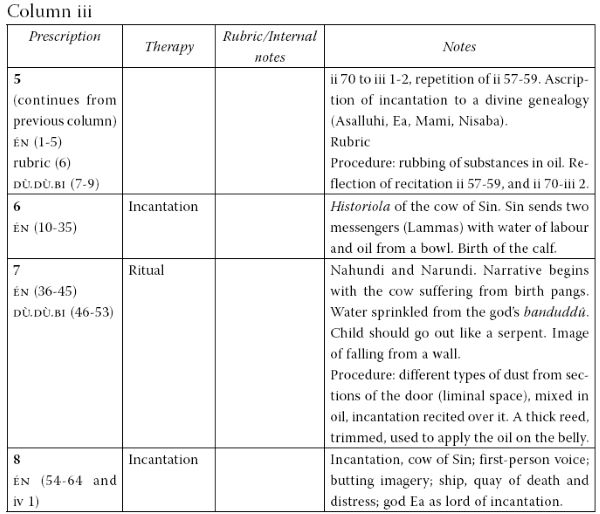

Rituals in BAM 248

The greater part of the tablet is constituted by rituals23, and by incantations alone, that is, recitations whose procedural part is not made explicit or remains unclear within the economy of the whole text24. The procedures or agenda that go together with the recitations in the ritual devices usually reflect and follow these images in the materia medica and the application methods employed. Most of the procedures, on the other hand, make use of fatty substances that are smeared on the belly of the woman in labour25. Let’s analyse prescription number 5 as an example. The incantation section in BAM 248 ii 70-iii 1-5 reads:

“Like the rain (lit. drop from heaven), he doesn’t …

Like (one) who falls off the wall, he doesn’t turn back.

Like a leaking pipe, [her waters] don’t remain (inside).

Incantation of Asalluhi, secret of [Marduk?].

This (is) reliable of Ea …, incantation of Mami […]

(The goddess) Nisaba gave (it) in order to keep the womb in order”.

This matches the procedure and vice versa:

“Its procedure. Stone of rain (lit. drop of heaven), dust of the revetment of a wall (that) has fallen,

Dust of a leaking pipe, you will mix (these) in oil from a bowl, from top

Downwards you will rub her and this woman will recover” (BAM 248 iii 7-9)26.

On similar grounds, materia medica related to doors and crossing places is used in a different ritual contained in the tablet (BAM 248 iii 46-53). These substances invoke the image of the pregnant mother as a closed space whose door must be wide-open and its threshold trespassed:

“Its procedure: dust of a crossroad, dust of the first threshold,

Dust of a box from the top and bottom,

Dust of the box of a door, a thick reed,

The tip and bottom you will trim,

You will mix these (kinds of) dust, you will throw them into oil,

You will recite the incantation seven times over this content (lit. inside),

You will fill the thick reed and on the top of her protruding belly

From top downwards you will rub”.

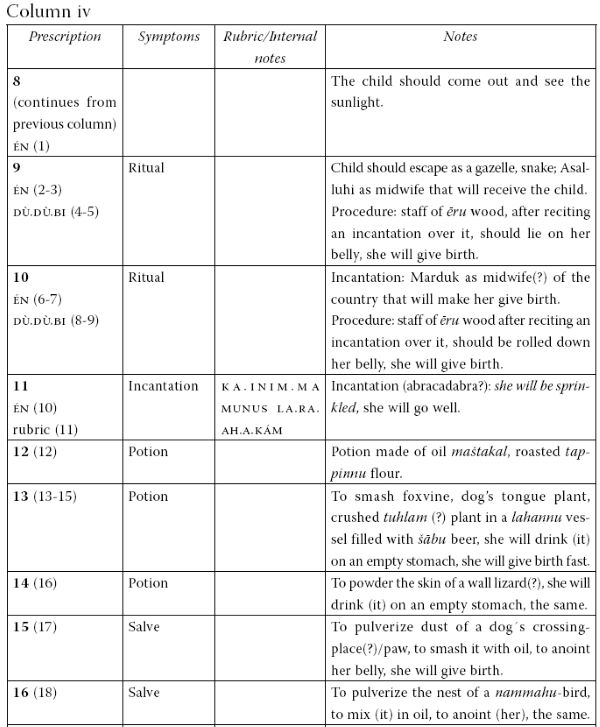

Other Therapeutic Approaches in BAM 248

Together with these traditions, the fourth column of the tablet lists other remedies of quite a different nature, to be used in helping to ease the process of giving birth. Remedies 12 to 20 are individual prescriptions separated by rulings and characterized mainly by the use of simplicia and two- and three-plant-based remedies applied as potions, ointments, or bands. The section BAM 248 iv 24-38, although similar in aim and form of treatment, differs from the previous section by the absence of rulings separating the different prescriptions. This element, together with the peculiar treatment described in BAM 248 iv 31-38, which specifies how to collect and apply the asû plant and that includes a sort of recitation in the form of an address to the plant itself, suggest the use of a different textual source in the composition of this fragment with regard to that employed for the case of remedies 12 to 20. The remedy section is closed by the inclusion of remedies to protect the newborn against the entities “hand of the god” and the (demon) lilû (remedies 29 to 32). In this case, as with the section BAM 248 iv 24-38, prescriptions are also not separated by rulings.

The Potions in BAM 248

The seven potions of the text make use of a limited number of materia medica, being mostly plants, but also including a few other substances, apparently of animal origin27. The reduced number of substances employed suggests a common, rather affordable type of remedy that was perhaps taken from a widespread popular knowledge and incorporated into learned written forms of knowledge. When confronted with the rituals in columns i to iii in the tablet, which would require not only the intervention of the āšipu or mašmaššu28, but also the use of substances such as different types of dust collected from a number of places, many of these other recipes appear to be more accessible.

Let’s have a look at these potions in more detail. The materia medica prescribed is usually to be crushed or grounded and administered in beer or oil. For the case of BAM 248, quantities are not specified. Recipe number 12 prescribes maštakal29 plant and tappinnu flour (a kind of second quality flour)30 in oil and/or beer31. The úIN.NU.UŠ/maštakal appears in a number of therapeutic contexts and ritual performances regarding the counteracting of witchcraft and transgression, as well as in cleaning activities. In fact, the menacing power of witchcraft over women’s healthcare is often explicitly stated in the cuneiform material32, and its use in our text may also be related to this fact33.

Another interesting feature alludes to the use of the same materia medica in different prescriptions, which are mentioned alone or differently combined with other substances. Prescription number 18 gives two alternative remedies in the same line: pulverized fox vine (gišGEŠTIN KA5.A)34 to be drunk in beer on an empty stomach; or dog’s tongue (úEME UR.GI7)35, prepared and administered in the same way. These two plants, which appear again in potion number 13, are also included as materia medica used to treat problems during childbirth in the herbals above-mentioned (see Appendix 1): BAM 381 iii 25-26 and BAM 380 rev. 31-32 “dog’s tongue”; BAM 381 iii 27-29 and BAM 380 rev. 33-35 “fox vine”. In the same way, powdered kur.kur/atā’išu36 plant drunk in beer (prescription 25) is the same remedy included in the herbals BAM 381 iii 31-32 and BAM 380 rev. 36-37.

Recipe number 13 increases the number of substances employed. For the same diagnosis as that in recipe 12, a combination of fox vine, dog’s tongue plant, and tuhlam (?) plant37 smashed together in a lahannu vessel filled with old beer is prescribed, specifying that it might be drunk on an empty stomach. Since lahannu38 seems to refer to a type of bottle or container of a rather small size, in this context it could be indicating a measure. Recipe 19 prescribed dog’s tongue and nīnû plant (úKUR.RAsar)39, while recipe 21 employs dog’s tongue plant and maštakal. In both cases the materia medica is to be pulverized and drunk with beer, on an empty stomach.

All in all, the substances of vegetable origin employed in the preparation of these concoctions are rather limited in number, but various combinations of these substances increase the potential number of potions available for easing birth.

Two potions employ animal-based products. Remedy 14 makes use of excrement of a wall lizard (?)40 drunk in beer on an empty stomach. A spotted wall lizard ([EME.D]IR IZ.ZI GÚN.A) is prescribed in another text on women’s healthcare from Assur aiming at “dropping the foetus”41. It may be hypothesized, therefore, that the substance is used in both cases because of its properties as expellant.

Prescription 20 offers some interpretative problems. The smashed U5(HU.SI) NÍG.IBmušen/rikibti arqabi that is prescribed has been usually translated in medical contexts as “bat guano”42, an interpretation that was taken after Miquel Civil43. The meaning of the term rikibtu, however, is far from clear, since it pertains to the semantic field of sexual intercourse more than to scatological vocabulary, and it might also be referring to “bat seed/semen” or to “”thumb” of a bat” (the nail or thorn at the top of the wing).

Just one potion (number 26) employs a kind of mineral paste or earth named IMKAL.GUG/ kalgukku44, which is frequently used in medicine in general and in the treatment of conditions affecting women in particular.

Cuneiform texts, and especially those of a technical nature as the prescriptions we have commented on so far, tend to be succinct and therefore avoid giving too much detail on aspects of dosage, preparation, and administration. However, we sometimes find relevant information in documentary sources. In the following Neo-Assyrian letter (SAA X 336: 1-rev. 4)45, information on the usual procedure on how to administrate a potion is given:

“Like any potion that my lord drinks, you put three drops into the libation bowl with the tip of a stylus and drink it before the meal (i.e. on an empty stomach). The water wherein it is mixed should be …. (terms difficult to translate follow)”.

Ointments and Salves

A number of remedies (15-17) involve the application of materia medica in oil or other fatty substances, which are usually smeared on the belly. This technique is also used in the complex rituals above mentioned, being attested from the Old Babylonian texts on childbirth.

In remedy 15, dust of a dog’s crossing-place(?)/paw46 should be smashed in oil and smeared on the belly; while remedy 16 prescribes the crushed nest of a SIM.MAHmušen/sinuntu bird47 applied in the same way. Although the sinuntu nest is seldom attested in medical contexts, it is interesting to note its use, on the one hand, in a remedy against witchcraft that combines, among other substances, úGEŠTIN.KA5.A, úIN.NU.UŠ and úKUR.KUR, all of them plants attested in BAM 24848. On the other, the nest of the sinuntu bird from the North, crushed and mixed in oil, is used in a ritual to calm down a child49.

The last salve (number 17) refers to the use of pulverized root of male gišNAM.TAR/pillû50 plant of the North in oil, which is then applied on the patient’s belly seven times from top to bottom.

Dietetic Prescriptions

We here use the term “dietetic” to allude to the prescription or forbidding of consuming certain foods in cases of health infirmities. It shouldn’t be mistaken, therefore, with the application of complex dietetic therapeutic systems as that exposed in the Hippocratic books, for example.

In BAM 248, meat of turtle51 (remedy 22), white pork52 (remedy 23) and vixen53 (remedy 24) are prescribed to the parturient. It is interesting to note that the fox and vixen54 reappear in the materia medica. While analysing the potions included in BAM 248, we have already talked about the use of the plant “fox vine”, which shares with the present line the writing KA5.A. It might therefore be argued that fox-related materia medica was considered to be effective to prompt childbirth, even though it is hard to say whether this effectiveness must be related to qualities that are associated with foxes in proverbs, fables and literary compositions in general. We could also be dealing with a term (“vixen meat”) alluding to a substance of vegetal origin that, because of its nomenclature (UZU/šīru “flesh, meat”), could have been included within the “dietetic” section.

The last remedy regarding food consumption corresponds to line BAM 248 iv 30, where allānkaniš or Kaniš nut55 is prescribed. The patient should chew it in her mouth to be able to give birth fast. This product seems to have been used in the treatment of medical conditions involving “constriction” (hiniqtu), in the sense of helping to expel what is stuck within the body.

The produce allānkaniš seems to have been a rather exotic and prestigious food that was imported from Anatolia through Kaniš, the area which gave the name to the fruit, into Northern Mesopotamia. On the other hand, turtle and pork seem also to have been rather valuable foodstuffs. As a consequence, we may be dealing here with remedies stemming from and being used by the elites. This, however, constitutes just a hypothesis, since our data on the accessibility to certain food products by the population are still rather poor.

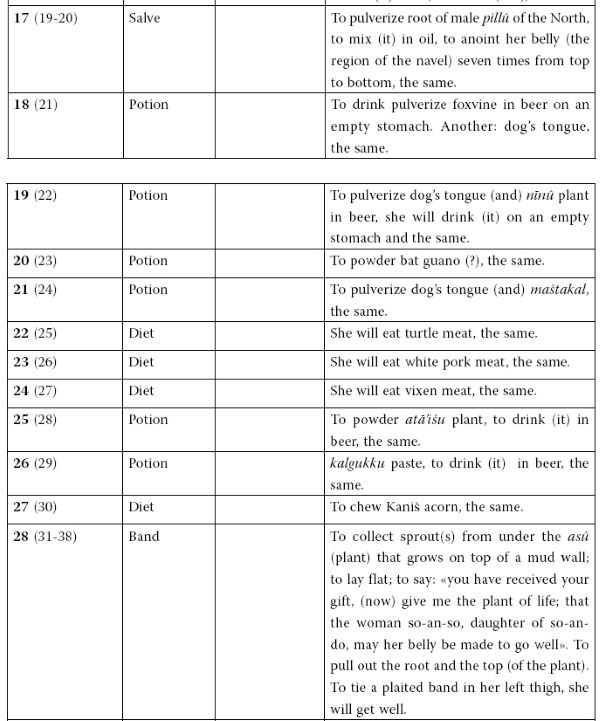

A Peculiar Band

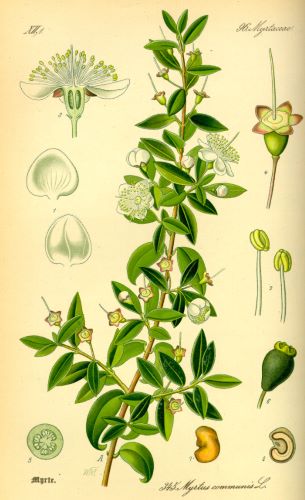

Remedy 28 is placed in BAM 248 following the “dietetic” prescriptions without being graphically separated from them. It gives thorough instructions on how to gather the plant asû so that its effectiveness is fully preserved, and includes a recitation that is formulated as a kind of dialogue with the plant itself56. It offers an unusual procedure that is but seldom attested in cuneiform texts, since no mention to the divine connections of the plant is made, suggesting a more direct and perhaps popular approach:

“If the same, you will collect sprout(s) from under the (plant of) myrtle

That comes out in the top of a mud wall; you will lay flat

And so you will speak, you will say:

“You have received your gift; (now) give me the plant of life.

That the woman so-an-so, daughter of so-an-do, may her belly be made to go well”.

This you should say, its root and its top you will pull out,

You won’t look at your back (i.e. you won’t turn back), you will speak with no man. You will tie a plaited band in her left thigh and she will get well”57.

The practice of root-cutting and plant harvesting for healing purposes has been better explored in the case of classical Greek and Latin sources. Theophrastus (371-287 BCE) in his Enquiry into Plants reports the activities of the Greek druggists (pharmacopolai) and root-cutters (rhizotomoi) and gives information on the procedures followed and the measures taken by these professional figures in the harvesting of healing plants, with some of them recalling observations similar to those in cuneiform texts58. More than Theophrastus’ opinions on the efficacy and sensibleness of these practices, however, what seems relevant here is his report on the specific ways of plant gathering regarding time, procedures, and prophylactic measures to be taken by the professional, and that provide food for thought to analyse both our particular case and the parallels in ancient healing practices in a broad sense.

A passage from Pliny’s Historia Naturalis on the virtues of the stomatice, arteriace or panchrestos (“good for all work”), useful to treat catamenia, echoes remedy 28 in the use of a branch that has not touched the ground (the reference in our text to the asû growing in the top of a wall could very well allude to this fact); as well as in the attachment of the materia medica in the upper (Pliny) or lower (BAM 248) part of the body, depending on whether the aim is to keep something up (e.g. blood or menses) or make something go down (e.g. the newborn):

“Similar virtues are attributed to a branch just beginning to bear, broken off at full moon, provided also it has not touched the ground: this branch, it is said, attached to the arm, is peculiarly efficacious for the suppression of the catamenia when in excess. The same effect is produced, it is said, when the woman herself pulls it off, whatever time it may happen to be, care being taken not to let it touch the ground, and to wear it attached to the body” (HN § 23.71; cfr. HN § 20.3 on the elaterium)”.

The healing technique of binding or attaching bands and strings with stones, metals and vegetable substances to different body parts is well known in cuneiform literature and, for the present case, in remedies regarding women’s healthcare59. Even though the specific medical properties of substances used in healing are but rarely specified, and in spite of the absence of an explicit theoretical thought in cuneiform sources in general, putting the evidence together seems to help getting insight on the rationale of certain forms of therapy. It might be argued, therefore, that the asû plant collected in this particular way (a specimen from the top of a wall, gathered while a recitation is said, etc) and applied to the thigh, that is, to the lower side of the body, would probably be conceived as a device capable of attracting the child towards the ground so as to facilitate childbirth.

Childbirth, Therapy, and Agency: Some Conclusions

The text BAM 248 exemplifies very well the kind of historic questions and methodological drawbacks that scholars working with cuneiform sources have to face. In this tablet, various healing techniques and approaches to deal with difficult childbirth are brought under the sphere of action of the āšipu, at least when it comes to textual codification and transmission. It is interesting to note the considerable variety in terms of techniques and degree of complexity in the therapies presented. We may advance the question, therefore, of how this collection of remedies took shape and through what channels these different healing devices came to be incorporated within the practice of Neo-Assyrian āšipūtu knowledge.

The texts being discussed emerged from the learned elites. They pose the question, therefore, of the significance of these remedies in terms of therapeutic availability and implementation at a large scale. Having been copied, compiled, gathered and studied in most cases by scribes, sages, and informed practitioners60, we should consider them to be examples of the medical practice the elites had access to. On the other hand, it might be argued that the therapies gathered could have been taken from a hypothetical variety of practical and intellectual levels. In fact, it is interesting to note the considerable variety in terms of techniques and degree of complexity of therapies present in BAM 248.

If we follow the thread of learned medical evidence, we get the picture of a predominantly male professional circle that would have intervened in all matters of female infirmities, while the specific and more technical tasks of the experience of childbirth would have been undertaken by the midwife. This, of course, is a vision strongly mediated by the written sources we must rely on. The interaction between or the possibility to have access to the expertise of a diversity of professionals, practitioners, and skilled people of various backgrounds, training and sphere of influence was probably more lively than the sources let us ascertain. The following passage from our text, however formulaic it might be61, suggests a division of activities in attendance at the birth. While the āšipu eases or opens the way of the child through ritual performance, it would be the duty of the midwife (šabsūtu) to attend the final stage of childbirth:

“Like Geme-Suen gave birth normally, may the young woman with difficulties in childbirth give birth. The midwife (should) not be delayed62, let the pregnant woman go well” (BAM 248 iii 33-35)63“.

We have but poor data regarding the activities of midwives, female healers, and attendants to childbirth at our disposal in comparison with the evidences we have for the male professionals who compiled written remedies to ease birth64. Midwifery is mainly attested in documentary sources, where midwives appear acting mainly as witnesses, owners of land, or participants in economic transactions. All the cuneiform texts we have concerning childbirth, when coming from well-documented archaeological contexts or when bearing colophons, report a male sphere of production. Writing doesn’t necessarily imply, though, that all the remedies quoted originally pertained to or derived exclusively from the “professional programme” of the āšipu (or the asû)65. The problem remains, therefore, how to verify the popular, learned, or “other” origin of a remedy; and, most importantly, to determine the degree of actual social implementation of the remedies recorded in written form. We have seen how a great deal of the contents in BAM 248 allude to a well-documented healing background that can be traced back at least to Old Babylonian written evidences, and which are based in ritual performances that would have required the intervention of the āšipu, not only because of their relative complexity, but most importantly, because of the status he held as representative and guardian of the healing knowledge of divine origin66. Those remedies in the fourth column of the tablet, on the other hand, make use of simplicia applied in potions and salves, and of dietetic advice that might have been available in common, although probably well-to-do, households. In the case of the peculiar band we have analysed in § 4.3, another therapeutic approach is given. Two traits, the absence of any mention of a divine figure, which are attested in other incantations and recitations involving the use of plants in ritual contexts lead by the cultic performer, on the one hand; together with the direct address to the asû plant, on the other, suggest differences in their origin and practical background. The āšipu might have used this wide range of therapies for reference, but it seems that their diversity and variable difficulty responds to different origins, degrees of accessibility, etc.

These therapies swing between theory and practice, between the mere written form and the reflection of contemporary healing techniques. These type of collections or compilations of remedies may also show different uses: they sometimes were made to respond to specific circumstances and needs67. A text originally compiled to respond to a particular need could very well have transcended the immediate use to become a reference work for copying, studying, exchange, etc. Whether the hypothetical original text behind BAM 248 could have served this purpose is, however, still a matter of further research.

See references at source.

Originally published by Dynamis 34:2 (Granada 2014), republished by SciELO under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial 4.0 International license.