The common image aside, it is not feasible for Wallace to have possessed a longsword during his lifetime.

By Dr. Laura S. Harrison

Cultural Resources Advisor

Historic Environment Scotland

Introduction

On the 28th of January 1912, G. Baldwin Brown of the University of Edinburgh wrote to the newspaper The Scotsman in support of the two-handed longsword1 that was to be depicted on the proposed statue of Sir William Wallace at Edinburgh Castle.2 Brown argued that ‘the sword is here as a symbol, not an effort at prosaic historical verity’.3 With this, Brown summarized the argument surrounding the ongoing depiction of Wallace with a longsword: despite a lack of evidence for Wallace having such a sword, he is almost exclusively portrayed with one. This chapter will consider depictions of Wallace with a longsword in order to consider where this legend may have come from, why it continues, and what affect this has on the overall Wallace tale, particularly in terms of his depiction as an idealized medieval masculine hero. It will also explore why the sword is considered to be authentic as Wallace’s weapon, despite widespread knowledge of its inaccuracy.

Wallace has become a common topic of commemoration in Scotland, reflecting the near-mythic status he achieved following his rebellion and eventual execution during the first Scottish War of Independence (1296–1328). The nineteenth and twentieth centuries see the rise of modern nationalism in Scotland, which partially involved the reframing of Scottish history to reflect Scotland as an entity that was historically separate from England. Certain periods and characters from history therefore became touchstones for Scottish nationalism, and Wallace’s failed rebellion during the medieval Wars of Independence was reframed with him in a martyr role fighting for Scottish independence. Though the history of the Wars of Independence is, inevitably, considerably more complicated, Wallace as a martyr for the Scottish cause has become the common narrative. The focus of this chapter will be on depictions of Wallace since 1800, which was the most popular period of commemoration for the medieval hero. In particular, the focus will be on showing the prevalence of his portrayal with a longsword. Several scholars have shown that it is not feasible for Wallace to have possessed a longsword during his lifetime, particularly because two-handed longswords did not appear in Scotland until the late fifteenth century, and the first definite use of them in a Scottish army was at the battle of Flodden in 1513, more than two hundred years after Wallace’s death.4 This has been the extent to which scholars have considered depictions of Wallace with a longsword, to indicate that it is inherently anachronistic. The goal of this chapter, then, is to go beyond this to illustrate the power of these ongoing depictions on the popular memory of Wallace.

It is in this dichotomy – that Wallace is often portrayed with a longsword despite the reality that he likely never even encountered one – that the difference between accuracy and authenticity can be seen. The question of accuracy versus authenticity has been common within the field of medievalism in terms of film, gaming and other forms of modern media, but it is less common in studies specifically on commemorations of medieval figures and events.5 One benefit of making a distinction between accuracy and authenticity is that it leaves room for the role of myth in commemoration. ‘Myth-busting’, as Stephanie Trigg has pointed out, is ‘an easy temptation for historians’.6 However, when looking at commemorations, what people believe happened in the past is often more pertinent than what actually occurred. Whatever transpired in the Middle Ages, the fact that people believe certain stories makes those stories real for purposes of commemoration. Though something may not be technically ‘accurate’ in a historic sense, if it feels authentic then it can swiftly become part of the historic landscape. Raphael Samuel and Paul Thompson have argued that historians should not discount the role of myths, saying ‘persistent blindness to myth undeniably robs us of much of our power to understand and interpret the past’.7 To study how people interact with the past, one has to embrace the role of myth.

There have been a number of studies that have specifically considered the myth of Wallace’s longsword. David Caldwell and Magnus Magnusson have both examined the veracity of the ‘Wallace Sword’ on display since the late nineteenth century at the National Wallace Monument. The history of this sword, as compiled by Charles Rogers in the late nineteenth century, is that following Wallace’s capture by English forces the sword was taken to Dumbarton, Scotland, where it was kept for 600 years until it was given to the National Wallace Monument by the commander of the garrison at Dumbarton in the mid-nineteenth century.8 Both Caldwell and Magnusson, however, have expressed doubts about this account. The sword only appears twice in the written record at Dumbarton, in 1505 and 1825, and there is uncertainty that these entries refer to the same sword.9 Work done on the sword has also shown it is a compilation of at least four swords. Three of these date from later than Wallace, but one of these may have come from the approximate time of the Wars of Independence. The best that can be said, then, is that this sword is perhaps the ‘ghost’ of Wallace’s sword, with the oldest part having potentially belonged to Wallace, though it is highly unlikely that will or could ever be proven.10 As Caldwell has suggested, ‘no serious scholar has in recent times been inclined to give the Wallace Sword any credence as the hero’s own.’11 No scholar has gone further in considering the sword than Caldwell and Magnusson, and they themselves have not examined the depictions contained in this chapter beyond the Wallace Sword itself. Though the realization that the Wallace Sword, both in theory and practice, is historically inaccurate is important, not going beyond that minimizes the lengths to which Wallace has been shown with the sword. As Andrew Elliott and Matthew Kapell have argued, ‘it is less interesting to note where and whether a given product deviates from the historical record, but rather for what reason it does so and what effect this might have.’12 This chapter, then, will address the reason and effect of this deviation.

Ultimately, this chapter will consider the impact the depictions of Wallace with a longsword have on his legacy and commemorations. The first section will briefly outline the potential origin of this myth, before the second section examines examples of the ways in which Wallace is shown with a longsword, in order to show the scale to which this occurs. These examples are a representative sample of the types of commemorations that show Wallace with a longsword, including monuments, art, texts, stained glass, films and public events. Though the time period of this study is from 1800 to the present, it is noteworthy that there is a significant lack of examples from the middle of the twentieth century. The Second World War marked a temporary departure from the trend of using the medieval past to rationalize events in the present.13 Following the First World War, there was a lot of effort to understand the conflict as part of a series of large-scale conflicts that occurred through history, including in the Middle Ages.14 The Second World War disrupted this theory, as it occurred so soon after the First World War, and interest in the medieval past generally decreased for several decades. It may also have been that the medieval history of Scotland seemed less relevant in light of the recent near-global conflict. A crucial change in this level of interest, particularly in terms of the Wars of Independence, was the release of the film Braveheart in 1995. Finally, the third section will then consider the ways in which these depictions influence how Wallace is remembered and memorialized in Scotland, in order to show how authenticity can become accuracy in commemorations. In particular, how it reinforces Wallace as an ideal of medieval military masculinity.

Origins of the Myth

The first question in considering the impact of Wallace’s longsword is where this myth began. Many point to the fifteenth-century minstrel Blind Hary’s poem Wallace, one of the best primary sources available for the life of Wallace, though it was written more than a century following his death. The text makes several references to Wallace’s sword, including describing ‘his good sword, that heavy was, and long.’15 However, Hary always describes Wallace using the sword one-handed, such as, ‘except a sword . . . which he took in his hand.’16 Hary’s suggestion that Wallace’s sword was ‘heavy and long’ could still have been the beginnings of this myth, however, as it is possible the heavy/long sword became a two-handed longsword once these were introduced in Scotland. Another potential source for the myth of Wallace’s longsword is the influence of the trope of the Highland warrior in Scotland. Depictions of Wallace, as well as another hero from the Wars of Independence King Robert I (Robert the Bruce), have often been used to draw a line between medieval military heroes and the idea of a historic Scottish military prowess. In addition, two-handed swords, most notably the claymore, are often attached to the image of the ideal Highland warrior. Perhaps to best frame Wallace as this idealized warrior, he needed to be shown with certain types of weapons.

Yet another origin for this myth could be the significant number of two-handed swords that belonged to important families within Scotland in this period. For example, at the laying of the foundation stone at the National Wallace Monument in 1861, there were six swords in attendance that were thought to date to the time of the Wars of Independence. These included the aforementioned ‘Wallace Sword’ that now resides in the monument itself; two swords said to be used by Sir John de Graeme, who fought alongside Wallace; a sword used in a battle during the Wars of Independence; a sword that apparently belonged to Robert the Bruce, which is still held by the Elgin family, descendants of Bruce; and a sword belonging to James Douglas, who fought with Bruce.17 The accuracy of all of these swords is now questioned by scholars, as they are all much larger than swords thought to be used during the period. As the Wars of Independence were one of the more popular historical periods during this time, perhaps there was a natural inclination to attempt to link these swords to Wallace and Bruce, rather than recognizing them as being from a later period.

Caldwell points to this wider popularity of historical relics in the nineteenth century as the origin of the ‘Wallace Sword’ myth, suggesting that the National Wallace Monument ‘clearly needed a relic of the nation’s favourite hero to heighten the feeling of awe and reverence amongst visitors’.18 Since the weapon now known as the Wallace Sword had a potential connection, it is clear this history was prioritized in order to help advertise the monument itself. In the nineteenth century, there were many more objects that were thought to date from this period than there are today. Teresa Barnett has suggested that while relics often only represent disparate random moments in history, ‘collectively they articulated a coherent historical vision’.19 The Wallace Sword helped people feel connected to wider Scottish history. A clear comparison to these historical relics is saints’ relics. Objects associated with saints were cherished because they are a potential source of sacred power, rather than as historical objects.20 However, both types of relics are similar in that they are seen as allowing for a direct connection between the past and the present.

Depictions of the Longsword

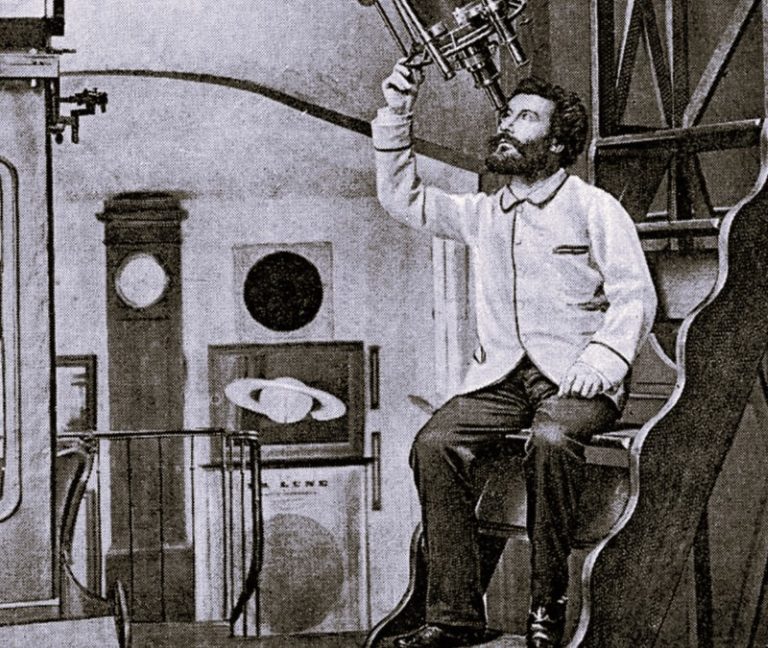

Regardless of how the myth began, by the beginning of the nineteenth century, Wallace was almost exclusively shown with a longsword. One of the earliest examples of Wallace with the longsword is a statue erected by David Steuart Erskine, the eleventh earl of Buchan, on his lands in Dryburgh in the Scottish borders (Figure 3.1). This 6.6-metre statue was built in 1814 and features possibly the largest of all Wallace’s swords. Monuments and statues are by far the richest examples in terms of the types of commemorations that include Wallace with a longsword, and he is also shown with one on at least four other statues in Scotland. One such example is a statue of Wallace erected in Aberdeen in 1888. The design was decided through public competition, for which twenty designs were submitted from both within the UK and internationally.21 The committee released a letter of support for the chosen design, stating, ‘the statue is 16ft. in height, being the largest and most important figure yet erected in Scotland’.22

Another example is the aforementioned statues of Wallace and Bruce that sit at the entrance to Edinburgh Castle (Figures 3.2 and 3.3). During the debates surrounding the form and placement of these statues, Stanley Cursitor, a member of the committee responsible for the statues, wrote to The Scotsman, ‘Wallace should not have a sword unknown in Scotland till 150 years after his death. It appears the deliberate perpetuation of a mistake is contrary to common sense.’23 The Wallace statue at Edinburgh Castle is displayed with one of the shortest swords of any of the examples, so Cursitor appears to have succeed with his concerns. That being said, Wallace’s sword is still larger than Bruce’s, which reinforces the idea that Wallace had a larger sword than was standard at the time. As will be seen in subsequent examples, this is a relatively common practice when both Wallace and Bruce are portrayed together with swords – Wallace’s tends to be larger than Bruce’s.

Though statues of Wallace use quite literal representations of the longsword, it can also be depicted on monuments in a more abstract manner. The Wallace Memorial (Figure 3.4) was built in 1912 in Elderslie in the west of Scotland, which is Wallace’s disputed birthplace. The design features a six-sided pedestal and a central column, which is entwined with a garland that is supposed to symbolize Wallace’s sword.24 Therefore, even when the longsword is not shown explicitly, it still features in the design process as a symbol that should be associated with Wallace.

The longsword also appears in other decorative acts of commemoration. Stained glass windows became popular in Scotland following the Disruption of the Kirk in 1843, when new churches were being built that incorporated stained glass into the design.25 James Ballantine & Sons were asked to create four windows to be installed in the National Wallace Monument in 1885.26 They are located on the second floor, in the Hall of Heroes. The Hall features sixteen busts of notable Scots, including Bruce. These windows feature Wallace, Bruce and two medieval warriors – a spearman and an archer. A guide from 1909 suggests the windows ‘exhibit carefully studied representations of the clothing and arms of the Scottish fighting men at the time of the War of Independence.’27 In the window dedicated to Wallace, the focal point is the outsized longsword he carries. This is particularly fitting as the Hall of Heroes and is also where the ‘Wallace Sword’ is kept. Wallace is shown in full armour, including a helmet and shield. He also carries a horn with him. The background is simple, and he is depicted standing on a small grassy hill.

Wallace is also shown with the longsword twice in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, the red sandstone Gothic building located in New Town in Edinburgh was built between 1885 and 1890. The funder and the architect for the project both envisaged that the building would be a ‘tribute to Scotland’s heroes’.28 This focus on celebrating Scotland’s history and heroes is indeed clear throughout the exterior and interior of the building. The exterior of the building is decorated with statues of figures from Scottish history. Wallace appears as a larger-than-life figure flanking the main entrance doors (Figure 3.5). He is pictured wearing chainmail and holding the longsword. The theme of celebrating Scotland’s heroes continues inside the gallery. The entrance hall is heavily decorated with murals, which were the responsibility of William Brassey Hole.29

Wallace is included in the processional frieze, which features 155 figures from Scottish history (Figure 3.6). The frieze has perhaps been most accurately described as ‘a confection of didacticism, antiquarian enthusiasm and a little artistic license’.30 Wallace is one of ten figures from the Wars of Independence depicted among these 155 figures from Scottish history. The weaponry included alludes to legends about the figures – Wallace is in possession of a longsword and Bruce has an axe, referencing the story of him killing Henry de Bohun with one stroke of an axe at the beginning of the Battle of Bannockburn. Bruce is also shown with a sword, though it is significantly smaller than Wallace’s.

There are also specific instances where the longsword is mentioned in texts. In the 1825 Popular Ballads and Songs, there is a song called ‘The Dirge of Wallace’, which contains the line ‘For his lance was not shiver’d on helmet or shield – And the sword that seem’d fit for Archangel to wield, Was light in his terrible hand!’.31 This suggests his sword was much larger than a standard sword but he was able to wield it, again likely alluding to his supposed height. Another example is the 1909 tourist book Guide to the National Wallace Monument, where William Middleton suggested the Wallace Sword used to be even larger, but that the point was broken off when it was sent to London for repair in 1825 and thus had to be shortened.32 Middleton did acknowledge that there was some doubt about the accuracy of the sword, but suggested these concerns were ‘without sufficient reason’.33

More recently, the myth of the sword has been propagated by the 1995 film Braveheart. In the film, the character of Wallace carries a 1.4-metre sword, and it also featured prominently in the official poster for the film. On a website that sells a replica of the sword, the inaccuracies of its use were justified by saying, ‘like the movie itself, it may not be historical – but it is inspired. It may not have been carried by heroes in the past, but it is representative of the swords they would have carried – an idealized weapon for an idolized character in film history.’34 Perhaps the best example of how associated the sword has become with Wallace comes from the slogan for the 700th anniversary celebrations of the Battle of Stirling Bridge in 1997, ‘Big man, Big sword, Big FUN’.35 This is clearly alluding to the popular idea that Wallace was much taller than the average man, which will be discussed below.

What is perhaps most astonishing is that in many of these examples people acknowledge the inaccuracies of portraying Wallace with a longsword, though that did not stop these depictions. This issue was particularly clear during the Glasgow International Exhibition in 1888 which brought together a large number of relics from the Scottish historical past, though there were no relics on display that were associated with Wallace. A newspaper article from August 1888 addressed this, saying, ‘there is not in the Bishop’s Castle a single relic associated with the name of Wallace, but that may be explained by the circumstance that it is doubtful whether any genuine personal memorial of that great chief really exists.’36 The article went on to discuss the existence of the Wallace Sword in the National Wallace Monument, explaining why it was not included, ‘but we fear the evidence which favours the claim would not be accepted by the modern investigator’.37 This article reveals that the authenticity of the relics in the exhibition was important to the public and it is clear there was some level of curation, as objects like the Wallace Sword were not admitted. That being said, there were objects included that were clear anachronisms, such as other two-handed swords apparently from the Wars of Independence. The same article reveals the important distinction between accuracy and authenticity.

With these relics certificates of authenticity are really a matter of secondary importance. There they are, objects which have been cherished with religious care for centuries. . . . Around them have clustered many traditions, and these traditions have so penetrated national life that they have attained the consistency and virtue of truth. It matters little now although we may be told by high authority that these things are not what they purport to be; they are sanctioned with the faith of centuries, their traditions would cling to them in spite of the clearest demonstration, and they will remain in all times the most cherished monuments of the great men with whose names they have so long and so intimately been associated.38

This author is arguing a point that historians of commemoration today still argue – that though objects may be historically inaccurate, they can gain authenticity over time.

Looking at depictions of Wallace in this period as a whole, despite the known inaccuracies he is shown with a longsword far more often than not. I gathered a collection of fifty depictions of Wallace for my doctoral thesis, representing the time period from 1800 to 1939.39 Of these, 75 percent of the depictions show him with a longsword. This illustrates the sheer scale of these depictions. The 25 per cent that do not depict him with one are largely text-based sources, which is significant as it is easier to identify Wallace by name in texts, rather than relying on iconography to reveal his identity. This is the first way the image of Wallace’s longsword impacts his legacy, which will be the focus for the remainder of this chapter.

Impact of the Longsword

The inclusion of a longsword with depictions of Wallace is important because it helps to identify who he is. In general, symbols are particularly useful when commemorating historical figures whose appearance was not captured in contemporary paintings. These symbols indicate identity when one’s physical appearance cannot. Therefore, the longsword is a clear indicator of Wallace’s identity, and is one of the key symbols through which he can be identified. To give a relevant comparison, Bruce is nearly always shown with a crown, especially when he is pictured alongside Wallace. This helps differentiate each man from the other. This also reveals why Wallace’s sword is often longer than Bruce’s when they are shown together – it helps to reveal his identity. For example, in the aforementioned processional frieze at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery in Edinburgh both Wallace and Bruce are shown with swords, though Wallace’s is significantly longer than Bruce’s (Figure 3.6).

This also reveals why some types of commemoration show Wallace with a longsword more than others. In physical commemorations such as monuments and stained glass windows, there is a nearly equal spread of times he is shown with a longsword versus the times when he is not. In texts, however, it is much more rare for the longsword to be mentioned, since an author can identify Wallace, whereas with other forms of commemoration there needs to be signs and symbols to reveal this information to the audience. Again, this reveals the role of the longsword as an indicator of Wallace’s identity.

The second way in which depictions of Wallace with the longsword impacts his legacy is that it helps to reinforce other ideas about him. Previously, I mentioned that Wallace is often described as being of above-average height. Caldwell begins his chapter on the history of the Wallace Sword by saying, ‘big men have big swords. None comes any bigger for the Scots than William Wallace.’40 In terms of historical figures, it is true that no one comes bigger in terms of historical figures of Scotland than Wallace. He has dominated interest in the Scottish medieval past for much of the period since 1800. However, the statement also alludes to this idea that Wallace was very tall. The sword helps reinforce this. The information panel beside the Wallace Sword in the National Wallace Monument says, ‘it is reasonable to assume that, in order to wield a sword of this size, Wallace would have had to be of considerable stature – at least six foot six inches in height.’41 Braveheart even addressed the fact that Mel Gibson, who played Wallace, is of average height. There is a scene in the film where a Scottish solider points out Wallace to another man, who says ‘can’t be, not tall enough’.42 The character of Wallace also references this himself, after a solider says, ‘William Wallace is seven feet tall!’ he replies, ‘Yes, I’ve heard.’43

In terms of historical veracity for Wallace’s height, it is difficult to determine. Hary’s Wallace and the fifteenth-century Scotichronicon both mention that he was taller than the average man, ‘he was a tall man with the body of a giant, cheerful in appearance with agreeable features, broad-shouldered and big-boned.’44 However, being tall is also a common trait for a medieval heroes. Gerald of Wales recounted how King Arthur’s bones were apparently recognized in the Middle Ages because of their sheer size.45 From Wallace’s own period Edward I, also known as Edward Longshanks, was apparently very tall. Edward (1330–76), the so-called Black Prince, was also thought to have been taller than average, or at least is portrayed as such on his funeral effigy and a surviving lead badge, ensuring that this would be the enduring memory of him.46 Even Bruce is often described as being of above-average height, and after the discovery of his bones in 1818 it was estimated he had been about six feet tall, though today that has been changed at 5’6” to 5’9”.47 The longsword may be a marker for apparent height, as Bruce is also displayed with a longsword in a number of occasions, though only about 17 percent of the time, as opposed to Wallace’s 75 percent. Clearly, one of several prerequisites for being a medieval hero is height, and every effort has been made to prove that Wallace fits that criterion. Wallace’s apparent height also helps reinforce the image of him as an ideal masculine hero, which is the final way the longsword impacts his memory.

The representation of Wallace as a large man with a large sword has obvious gender implications. Swords are often seen as a phallic symbol of masculinity, and Goran Stanivukovic has described the sword as ‘the archetypal masculine symbol of sexual prowess’.48 This can be seen in many studies of medieval literature, both from a medievalist and a medievalism angle. For example, Jennifer Dukes-Knight has examined masculinity in the early Irish text Táin Bó Cúailnge.49 She compares the depiction of Fergus in other texts in the Ulster Cycle when he is the epitome of masculinity, particularly due to his ‘enormous size and sexuality, and the Tidings of Conchobar Mac Nessa lists . . . the amount of food and women required to satisfy his various appetites . . . .’50 In Tá i n, however, Fergus’ sword is stolen and his story is one of emasculation and overall decline as both a hero and a lover.51 To take a more modern example, Andrea Wright has written about Sonja from the 1985 film Red Sonja, who is the victim of sexual and other violence in childhood and becomes an accomplished swordswoman.52 She makes ‘a vow not to form an intimate relationship with any man until she finds one who can beat her in a fight with the phallic sword . . . .’53 Wright makes the argument that despite her masculinized appearance and actions, she is still sexualized as a character, illustrating how powerful masculinity and a sexual appetite go hand in hand.

Wallace, with the longsword, is the epitome of medieval military masculinity – in terms of his height, the size of his sword, his military prowess in life, and also his influence since death. This is particularly important in terms of the Scottish identity, as it reinforces a strong martial history. It also acts as a symbol of his status. Richard Boothby has argued that ‘traditions of costume have long required the man in charge to carry a big stick’.54 Depictions of Wallace with the longsword reinforce the popular notion that he was an ideal military hero in the Middle Ages, placing him as an important player in the history of Scottish militarism.

It is clear the longsword plays a crucial role in how Wallace is remembered. It helps to identify who he is; it reinforces aspects of his appearance and strengthens his image as an ideal solider. Elliott coined the word ‘historicon’ to describe ‘an indicator of a historical period’.55 Wallace’s longsword could easily fall into this category – it is immediately recognizable as signalling not only Wallace’s identity but also the wider period of the Wars of Independence, and also alludes to the tradition of Scottish military prowess that is still so relevant in Scotland.

Conclusion

Overall, the example of Wallace and the longsword shows the difference between accuracy and authenticity. Though it is not accurate for Wallace to be portrayed with a longsword, it is authentic due to the sheer amount of representations. This case study of the impact of one relic on wider commemoration also shows the intricate ways in which commemorations relate to each other. As more commemorations were created that depicted Wallace with the longsword, it further enforced that this was the ‘correct’ image of him. Wallace’s sword is not just a weapon but rather a symbol of the popular assumptions of who he was and what he stood for. What is particularly interesting about this is the dichotomy that people are often very invested in historical accuracy when undertaking commemorative acts, though they are often actually referring to authenticity. The title of this chapter refers to the quote from Stanley Cursitor about the Wallace statue located at Edinburgh Castle, suggesting that perpetuating a known myth is against common sense. Though this is a logical view, it is clear that the image of Wallace with a longsword is much more nuanced then this. The image impacts his legacy in three ways: it indicates who he is in commemorations, it reinforces other myths about him, and it alludes to his reputation as an ideal example of military masculinity. It is clear that simply relegating Wallace’s longsword as a myth is missing its profound impact on his legacy. Indeed, though Wallace did not have a longsword in the fourteenth century, he certainly does in the twenty-first.

Endnotes

- National Records of Scotland: ‘Wallace and Bruce Memorial: Edinburgh Castle’, RF 2/14; A note on terminology: the term ‘longsword’ is being used here because it describes the sword – it is longer than the average sword, and thus would need to have been used with both hands.

- G. Baldwin Brown, ‘Letters from Readers’, The Scotsman, 12 January 1912.

- Ibid.

- David Caldwell, ‘The Wallace Sword’, in The Wallace Book, ed. E .J. Cowan (Edinburgh: Birlinn Limited, 2007), 172; Magnus Magnusson, Scotland: The Story of a Nation (London: HarperCollins, 2000).

- See: Andrew B. R. Elliott, Remaking the Middle Ages: The Methods of Cinema and History in Portraying the Medieval World (Jefferson: McFarland, 2011); A. Keith Kelly, ‘Beyond History Accuracy: A Postmodern View of Movies and Medievalism’, Perspicuitas (2004).

- Stephanie Trigg, ‘Medievalism and Convergence Culture: Researching the Middle Ages for Fiction and Film’, Parergon 25, no. 2 (2008): 109.

- Raphael Samuel and Paul Thompson, ‘Introduction’, The Myths We Live By, ed. Raphael Samuel and Paul Thompson (London: Routledge, 1990), 4–5.

- Charles Rogers, The National Wallace Monument (Edinburgh: John Menzies, 1860).

- Ibid.; Caldwell, ‘The Wallace Sword’, 172.

- Magnusson, Scotland: The Story of a Nation.

- Caldwell, ‘The Wallace Sword’, 172.

- Andrew B. R. Elliott and Matthew Wilhelm Kapell, ‘Introduction: To Build a Past That Will “Stand the Test of Time”—Discovering Historical Facts, Assembling Historical Narratives’, in Playing with the Past: Digital Games and the Simulation of History, ed. Matthew Wilhelm Kapell and Andrew B. R. Elliott (New York and London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013), 8.

- Stefan Goebel, The Great War and Medieval Memory (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 13.

- Ibid., 14.

- William Hamilton, Blind Harry’s Wallace (Edinburgh: Luath Press Ltd, 1998), 7:1, 101.

- Ibid., 2:4, 23.

- William Middleton, Guide to the National Wallace Monument (Stirling: W. Middleton, 1909), 10–11.

- Caldwell, ‘The Wallace Sword’, 169.

- T. Barnett, Sacred Relics: Pieces of the Past in Nineteenth-Century America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013), 28.

- Ibid., 18.

- ‘Competitive Designs for the Wallace Statue in Aberdeen’, Aberdeen Weekly Journal, 5 July 1884.

- Ibid.

- National Records of Scotland: ‘Wallace and Bruce Memorial: Edinburgh Castle’, RF 2/14.

- ‘Wallace Memorial at Elderslie’, Aberdeen Daily Journal, 25 September 1912.

- Michael Donnelly, Scotland’s Stained Glass: Making the Colours Sing (Edinburgh: The Stationery Office/Historic Scotland, 2007), 25.

- The National Wallace Monument, ‘Stained Glass Windows’, http://www.nationalwallacemonument.com/the-monument/stained-glass-windows/, accessed 31 January 2017.

- Middleton, Guide to the National Wallace Monument, 23.

- National Galleries Scotland, ‘About the Portrait Gallery’, https://www.nationalgalleries.org/visit/about -the-portrait-gallery/, accessed 15 November 2016.

- Elizabeth S. Cumming, ‘Hole, William Fergusson Brassey’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, http://www.oxforddnb.com.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk/view/article/100749.

- Helen E. Smailes, ‘A Pride of Lions: Noel Paton and the National Wallace Monument’, Architectural Heritage 25 (2014): 85.

- Author unknown, Popular Ballads and Songs, from Tradition Manuscripts, and Scarce Editions (Paris, 1825).

- Middleto10.n, National Wallace Monument, 22.

- Ibid., 22.

- Darksword Armoury, ‘The William Wallace Scottish Claymore Sword – Braveheart Sword (#1362)’, http://www.darksword-armory.com/medieval-weapon/medieval-swords/william-wallace-scottish-claymore-sword-braveheart-sword-1362/, accessed 30 March 2018.

- Graeme Morton, William Wallace: A National Tale (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press Ltd, 2014), 70.

- ‘Glasgow International Exhibition’, Glasgow Herald, 29 August 1888.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- This information is taken from my PhD thesis, which was submitted to the University of Edinburgh in March 2018.

- Caldwell, ‘The Wallace Sword’, 169.

- Magnusson, Scotland: The Story of a Nation, 126.

- Braveheart, dir. Mel Gibson, Paramount Pictures (1995).

- Ibid.

- Walter Bower, A History Book for Scots: Selections from Scotichronicon, ed. D. E. R. Watt (Edinburgh: Mercat Press, 1998), 186.

- Richard White, ed., King Arthur in Legend and History (London: Routledge, 1997), 517.

- R. Barber, ‘Edward, Prince of Wales and of Aquitane’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-8523.

- ‘Royal Dunfermline: King Robert the Bruce’, Royal Dunfermline website, accessed 3 December 2016. http://www.royaldunfermline.com/Resources/DUNFERMLINE _AND_ROBERT_THE_BRUCE.pdf.

- Goran Stanivukovic, ‘“The Blushing Shame of Soldiers”: The Eroticism of Heroic Masculinity in John Fletcher’s Bonduca’, in The Image of Manhood in Early Modern Literature, ed. Andrew P. Williams (London: Greenwood Press, 1999), 46.

- Jennifer Dukes-Knight, ‘The Wooden Sword: Age and Masculinity in “Táin Bó Cúailnge”’, Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium 33 (2013): 107–22.

- Ibid., 111.

- Ibid., 111–12.

- Andrea Wright, ‘A Sheep in Wolf ’s Clothing? The Problematic Representation of Women and the Female Body in 1980s Sword and Sorcery Cinema’, Journal of Gender Studies 21, no. 4 (2012): 403.

- Ibid., 403.

- Richard Boothby, Sex on the Couch (London: Routledge, 2005), 4.

- Elliott, Remaking the Middle Ages, 210–11.

Chapter 3 (43-57) from The Middle Ages in Modern Culture: History and Authenticity in Contemporary Medievalism, edited by Karl C. Alvestad and Robert Houghton (Bloomsbury Academic, 10.07.2021), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.