The life of Albert Einstein demonstrates that intellectual freedom often emerges in opposition to institutions designed to cultivate it.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Genius Misread by Institutions

The early life of Albert Einstein stands in sharp tension with the later mythology of effortless genius. Popular memory tends to collapse his biography into inevitability, portraying intellectual brilliance as immediately recognizable and universally affirmed. In reality, Einstein’s formative years were marked by misunderstanding, frustration, and institutional resistance. His struggles as a student reveal less about personal deficiency than about the rigid expectations embedded within nineteenth-century educational systems that privileged obedience over inquiry.

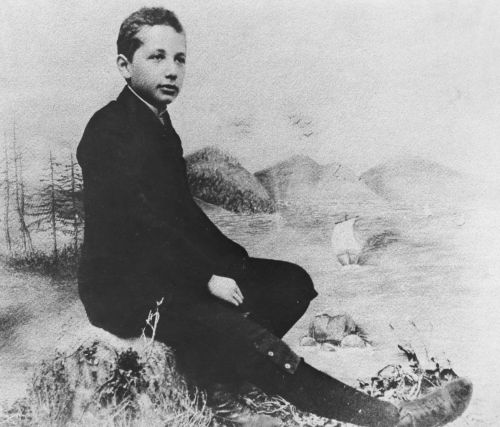

From a young age, Einstein appeared out of step with conventional measures of intellectual development. His parents worried that he might have a learning disability, particularly because of his delayed speech and inward temperament. In an era that equated intelligence with verbal fluency and rapid memorization, such traits were easily misread as signs of limitation. These early anxieties contributed to a sense of difference that would shape Einstein’s relationship with authority and evaluation. Rather than encouraging exploration, institutions responded with suspicion toward a child who did not conform to prescribed norms.

As Einstein entered formal schooling, this tension intensified. The German Gymnasium system emphasized rote learning, strict discipline, and reverence for authority, conditions that clashed fundamentally with his intellectual disposition. Einstein questioned premises, challenged explanations, and sought conceptual clarity rather than mechanical repetition. Teachers interpreted this behavior as insolence rather than curiosity, reinforcing the perception that he was a problematic student. Academic performance suffered not because of incapacity, but because the system rewarded compliance over understanding.

What follows argues that Einstein’s early educational struggles were the product of a profound mismatch between institutional expectations and an emerging mode of thought grounded in questioning, imagination, and independence. His later rejection of authoritarian religion and embrace of a non-personal, law-governed universe followed the same epistemological trajectory that had brought him into conflict with formal schooling. To understand Einstein’s intellectual and spiritual development, it is therefore essential to examine how institutions misread his genius, mistaking resistance to authority for failure and conformity for intelligence.

Early Childhood, Anxiety, and the Fear of Deficiency

In his earliest years, Einstein was already marked as unusual, not for precocious brilliance but for developmental patterns that unsettled those around him. He spoke later than expected, often hesitating before answering and preferring careful formulation over quick response. In a family attentive to intellectual achievement and social respectability, this delay provoked genuine concern. His parents worried that something was wrong, that their child might be intellectually impaired rather than merely different. Such anxiety reflected broader nineteenth-century assumptions about intelligence as a measurable, linear progression rather than a diverse set of cognitive styles.

These early fears were not neutral. They shaped the emotional environment in which Einstein developed, fostering an acute awareness of being evaluated and judged. The possibility of deficiency lingered as a silent pressure, encouraging inwardness and self-scrutiny. Einstein learned early that difference could be interpreted as failure, a lesson that would deepen his skepticism toward external assessments of worth. Rather than responding by striving to perform intellectual normalcy, he retreated further into solitary reflection, cultivating habits of thought that unfolded privately rather than performatively.

The educational culture of the time offered little accommodation for such inward development. Intellectual promise was expected to manifest through rapid recall, verbal agility, and visible compliance. Einstein’s preference for slow deliberation and conceptual depth ran counter to these expectations. What teachers and adults perceived as hesitation or deficiency was, in fact, an emerging commitment to understanding before expression. This mismatch between internal cognition and external measurement contributed to a growing sense of alienation from institutional judgment.

Yet this early anxiety also fostered resilience. Being misread compelled Einstein to rely less on external validation and more on internal coherence. The fear of deficiency, once internalized, transformed into a determination to trust reason over reputation and insight over approval. These formative experiences did not merely precede his later conflicts with schooling. They prepared him for a life defined by intellectual independence, skepticism toward authority, and a refusal to accept imposed definitions of ability or value.

Rote Learning and the Violence of Pedagogy

As Einstein advanced into formal schooling, the incompatibility between his intellectual temperament and institutional pedagogy became unmistakable. The German Gymnasium system he encountered was rigidly hierarchical, emphasizing memorization, obedience, and deference to authority. Knowledge was treated as something to be recited rather than understood, and teachers functioned as enforcers of discipline rather than guides to inquiry. For a student whose thinking depended on questioning first principles, this environment proved stifling rather than formative.

Einstein experienced this pedagogical model as intellectually coercive. Rote learning demanded submission to prescribed answers, discouraging curiosity and penalizing deviation. The classroom was structured to reward speed, repetition, and conformity, not conceptual exploration. Einstein later described such schooling as antithetical to genuine understanding, arguing that it trained memory at the expense of thought. In this context, education became an exercise in control, shaping students to fit institutional expectations rather than cultivating independent reasoning.

The teachers who administered this system often interpreted Einstein’s resistance as moral failure rather than pedagogical critique. His insistence on asking foundational questions unsettled instructors who were unprepared or unwilling to move beyond the curriculum. When they could not answer his inquiries, authority itself was exposed as fragile. Rather than adapt, teachers labeled him disrespectful and insubordinate. Pedagogy thus operated not merely as instruction but as discipline, enforcing intellectual submission through humiliation and threat.

This dynamic constituted a form of educational violence, not in the physical sense alone, but in its suppression of intellectual autonomy. Einstein’s schooling taught him that institutions could mistake obedience for intelligence and compliance for virtue. Far from refining his abilities, such pedagogy attempted to flatten them. His rejection of rote learning was therefore not adolescent contrariness but a principled refusal to accept an educational system that treated thought as a liability. The experience left a lasting imprint, shaping his lifelong opposition to authoritarian structures in both education and belief.

Rebellion, Isolation, and Academic Struggle

Within the rigid confines of institutional schooling, Einstein increasingly assumed the role of the rebel, not through deliberate provocation but through persistent refusal to suppress his intellectual instincts. He asked questions that challenged assumptions, probed explanations that relied on authority rather than reason, and resisted the expectation that knowledge should be accepted without understanding. These behaviors, interpreted by teachers as insolence, placed him in direct conflict with educational structures that equated discipline with learning.

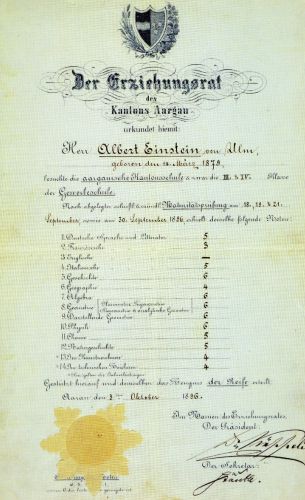

This rebellion came at a personal cost. Einstein’s teachers frequently regarded him as disruptive and disrespectful, particularly because his questions exposed their own limitations. Rather than fostering dialogue, classrooms closed ranks against him. Academic evaluations reflected this hostility, with poor grades serving as institutional markers of failure. Such assessments did not measure comprehension or insight but compliance. In an environment hostile to deviation, intellectual independence was translated into academic deficiency.

Social isolation accompanied institutional rejection. Einstein found few peers who shared his intellectual curiosity or tolerance for nonconformity. The classroom, rather than functioning as a community of learning, became a site of estrangement. Loneliness intensified his inward orientation, pushing him further toward solitary study and contemplation. Yet this isolation also insulated him from the pressure to conform, allowing him to pursue lines of thought unencumbered by peer approval.

Academic failure, in this context, was less a reflection of inability than of incompatibility. Einstein’s poor performance signaled a profound mismatch between his cognitive style and the metrics used to evaluate it. The educational system mistook intellectual resistance for incompetence, confusing obedience with understanding. This experience reinforced Einstein’s skepticism toward institutional judgment and prepared him to pursue knowledge outside sanctioned pathways, even at the cost of formal recognition.

Leaving School at Fifteen: Intellectual Flight

At the age of fifteen, Einstein made the consequential decision to leave formal schooling altogether, a move that crystallized years of frustration and alienation. This departure was not impulsive but the culmination of sustained conflict with an educational system he experienced as coercive and intellectually barren. Disgusted by rote memorization, rigid discipline, and teachers who equated authority with knowledge, Einstein chose withdrawal over continued submission. Leaving school marked a decisive break with institutional pedagogy and an assertion of intellectual self-preservation.

The act of leaving was also an act of relief. Freed from the daily pressures of conformity and surveillance, Einstein experienced a renewed sense of autonomy. Outside the classroom, learning no longer functioned as a performance evaluated by hostile authorities but as an internal pursuit guided by curiosity. This psychological shift was crucial. Removed from an environment that pathologized his questions, Einstein could explore ideas without fear of punishment or ridicule. Intellectual freedom replaced academic anxiety.

During this period, Einstein immersed himself in independent study, particularly in mathematics and physics. Without curricular constraints, he engaged deeply with problems that fascinated him, following conceptual threads wherever they led. This self-directed learning fostered habits of sustained concentration and imaginative experimentation that formal schooling had actively discouraged. Education, reclaimed on his own terms, became exploratory rather than prescriptive, emphasizing understanding over recitation.

Leaving school also reinforced Einstein’s skepticism toward institutional authority more broadly. The decision confirmed his belief that systems claiming to educate could, in practice, obstruct genuine learning. Authority unmoored from understanding appeared not merely inefficient but morally suspect. This conviction would later surface in his opposition to dogmatic thinking in both science and religion, as well as in his resistance to hierarchical power structures more generally.

Rather than halting Einstein’s intellectual development, the decision to leave school accelerated it. Intellectual flight replaced institutional stagnation. The years following his departure demonstrated that education need not be tethered to classrooms to be rigorous or transformative. For Einstein, leaving school was not an abandonment of learning but a strategic escape from an environment hostile to the very qualities that would later define his contributions. It marked the moment when education ceased to be imposed and became chosen.

Science as an Alternative to Religious Authority

For Einstein, the rejection of traditional religious belief followed a trajectory strikingly similar to his rejection of authoritarian schooling. Both institutions, as he encountered them, demanded submission to inherited answers rather than understanding grounded in reason. From an early age, Einstein recoiled from doctrines that presented truth as fixed and unquestionable. Just as rote pedagogy stifled intellectual growth, religious dogma appeared to him as an imposed framework that discouraged inquiry into the nature of reality.

Einstein’s early exposure to religious instruction initially sparked curiosity, but this interest quickly gave way to disillusionment. The narratives and rituals of traditional religion, particularly those centered on a personal, interventionist God, failed to withstand his growing commitment to rational explanation. Privately, he regarded scriptural literalism as intellectually immature, describing biblical stories as primitive attempts to explain a universe that demanded deeper scrutiny. This rejection was not merely emotional. It arose from the same insistence on coherence and evidence that had placed him at odds with educational authority.

Science offered an alternative epistemology. Where religion relied on revelation and tradition, science promised understanding through observation, mathematics, and testable laws. For Einstein, scientific inquiry did not require submission to authority but encouraged skepticism toward it. Knowledge emerged not from obedience but from questioning, experimentation, and conceptual elegance. Science thus became a refuge for intellectual integrity, providing a framework in which doubt was not a moral failing but a methodological necessity.

Importantly, Einstein did not replace religious dogma with scientific arrogance. He remained acutely aware of the limits of human understanding and rejected simplistic claims of certainty. His commitment to science was accompanied by humility before the complexity of nature. Unlike religious systems that claimed moral authority through divine command, science offered provisional truths always subject to revision. This openness aligned with Einstein’s ethical sensibilities, shaped by early encounters with institutional rigidity and punishment.

Einstein’s stance placed him at odds with both traditional believers and militant atheists. He resisted labels, often identifying himself as an agnostic or religious nonbeliever while rejecting the reduction of the universe to mere randomness. His opposition was directed not at spirituality itself but at institutions that claimed to mediate ultimate truth. Science, for Einstein, did not negate wonder. It deepened it by revealing order, symmetry, and intelligibility without invoking supernatural intervention.

In this way, science functioned as an alternative moral and intellectual authority in Einstein’s life. It allowed him to pursue meaning without submission, reverence without obedience, and ethics without commandment. The same intellectual independence that led him to abandon coercive schooling guided his departure from traditional religion. Both decisions reflected a consistent commitment to understanding over compliance, a principle that would shape his scientific work and his enduring philosophical outlook.

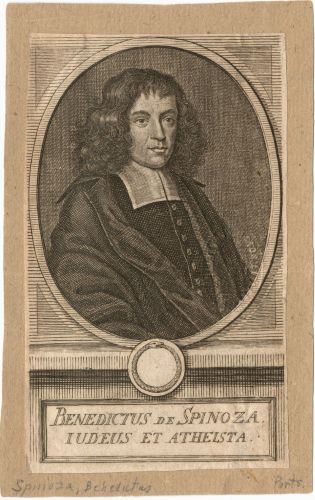

“Spinoza’s God” and Cosmic Reverence

When Einstein spoke of believing in “Spinoza’s God,” he was not offering a cryptic compromise between science and religion but articulating a coherent philosophical position rooted in natural order. By invoking Baruch Spinoza, Einstein aligned himself with a conception of divinity stripped of personality, will, and intervention. God, in this sense, was not a being who listened, judged, or acted in history, but the rational harmony of the universe itself. This view rejected the anthropomorphic God of tradition while preserving a language of reverence for existence.

Einstein’s attraction to Spinoza lay in the philosopher’s identification of God with the lawful structure of nature. Reality was intelligible not because it was overseen by a moral overseer, but because it was governed by consistent principles accessible to reason. For Einstein, this alignment resolved a tension that plagued both religion and materialism. It preserved wonder without surrendering to superstition and affirmed meaning without invoking supernatural causation. The universe inspired awe precisely because it obeyed laws rather than whims.

This position was frequently misunderstood. Popular audiences often interpreted Einstein’s language of God as evidence of latent theism, selectively quoting him to suggest belief in a personal deity. Einstein repeatedly rejected these interpretations, clarifying that he did not believe in a God who rewarded and punished or who intervened in human affairs. His reverence was directed toward order, beauty, and intelligibility, not toward prayer or worship. The persistence of misinterpretation revealed how deeply personal theism dominated cultural assumptions about belief.

Einstein’s cosmic reverence functioned as an emotional and ethical orientation rather than a religious doctrine. He described a profound sense of humility before the vastness and coherence of nature, a feeling that inspired both scientific inquiry and moral restraint. This reverence did not issue commandments or promises of salvation. Instead, it fostered responsibility grounded in understanding. To comprehend the universe was, in a limited but meaningful sense, to participate in its order.

By embracing “Spinoza’s God,” Einstein articulated a spirituality compatible with scientific rigor and intellectual freedom. It offered continuity with his earlier rejection of authoritarian schooling and dogmatic religion, both of which demanded assent without understanding. Cosmic reverence required no submission to authority, only attentiveness to reality as it is. In this framework, science became not the enemy of spirituality but its most disciplined expression, revealing a universe worthy of awe precisely because it was governed by law rather than command.

Science as Spiritual Discipline

For Einstein, science was not merely a technical enterprise but a disciplined mode of spiritual engagement with reality. Stripped of dogma and supernatural claims, it nevertheless demanded humility, patience, and ethical seriousness. Scientific inquiry required submission not to authority but to evidence, coherence, and mathematical necessity. In this sense, science functioned as a rigorous discipline of the mind and character, shaping how one approached truth, uncertainty, and responsibility.

Einstein often spoke of a “cosmic religious feeling,” a phrase that puzzled both theologians and positivists. What he meant was not belief in doctrines or rituals, but a profound emotional response to the rational structure of the universe. The discovery that nature obeys elegant, comprehensible laws inspired a sense of awe comparable to religious reverence. This feeling did not culminate in worship but in sustained inquiry. To study physics was to participate in an ongoing encounter with order, one that demanded intellectual honesty and reverence for truth.

This discipline imposed ethical constraints. Einstein rejected superstition, miracle thinking, and appeals to authority precisely because they short-circuited understanding. Science required restraint from claiming more than evidence allowed. Such restraint, he believed, cultivated moral seriousness by discouraging arrogance and certainty. The scientist, like the philosopher, was obligated to accept limits, acknowledging how much remained unknown. This posture contrasted sharply with religious systems that claimed access to ultimate answers through revelation.

Einstein also understood science as a counterweight to nihilism. While rejecting a personal God, he refused to interpret the universe as meaningless or chaotic. The existence of lawful structure suggested intelligibility, even if ultimate purpose remained inaccessible. Meaning emerged not from divine intention but from participation in understanding. The pursuit of knowledge itself became a source of dignity and orientation, grounding ethics in comprehension rather than commandment.

In this way, science served Einstein as a spiritual discipline without theology. It demanded devotion without worship, humility without submission, and awe without illusion. The habits cultivated through scientific inquiry mirrored those he valued most deeply: independence of thought, respect for reality, and moral seriousness rooted in understanding. Science did not replace religion for Einstein. It rendered religion unnecessary by providing a disciplined, honest, and enduring way to encounter the profound order of the universe.

The Misuse of Einstein by Popular Religion

The public reputation of Einstein has been repeatedly appropriated by popular religion in ways that distort both his words and his philosophical commitments. Isolated quotations referencing “God” are frequently extracted from their context and redeployed as evidence that Einstein ultimately affirmed traditional theism. These appropriations often ignore his explicit rejections of a personal, interventionist deity, substituting rhetorical convenience for intellectual accuracy. The result is a sanitized Einstein whose complexity is sacrificed to apologetic utility.

Einstein himself was acutely aware of this tendency and expressed frustration with it during his lifetime. He repeatedly clarified that his use of religious language was metaphorical, not confessional. References to God functioned as shorthand for the lawful order of nature, not an endorsement of prayer, providence, or divine judgment. Yet the persistence of misquotation reveals a deeper cultural discomfort with non-theistic reverence. For many audiences, awe without worship appears unintelligible, requiring reinterpretation through familiar religious categories.

This misuse reflects a broader pattern in which scientific authority is conscripted to validate religious belief. Einstein’s stature as a cultural icon makes him particularly attractive for such appropriation. By presenting him as a covert believer, religious narratives seek to reconcile modern science with inherited doctrine without confronting the epistemological tensions between them. In doing so, they transform Einstein into a symbolic endorsement rather than a historical thinker with carefully articulated views.

The distortion also erases Einstein’s explicit critiques of organized religion. In private correspondence and public statements, he characterized traditional religious beliefs as anthropocentric and intellectually immature. He rejected the notion of divine reward and punishment, viewing such ideas as projections of human desire rather than insights into cosmic reality. To omit these positions while celebrating his language of reverence is to misrepresent the substance of his thought while retaining its aesthetic appeal.

Ironically, this appropriation undermines the very ethical seriousness Einstein associated with spirituality. His cosmic reverence demanded intellectual honesty and resistance to comforting illusions. By reshaping his views to fit conventional belief systems, popular religion reproduces the same authoritarian tendencies Einstein rejected in both schooling and theology. Authority is preserved at the expense of understanding, and complexity is flattened into affirmation.

The misuse of Einstein thus serves as a cautionary example of how intellectual figures are posthumously reshaped to serve institutional needs. It reveals the difficulty many cultures have in accepting forms of meaning that do not culminate in worship or doctrine. Einstein’s legacy resists such simplification. His thought insists that reverence for order does not require belief in a personal God and that intellectual integrity must not be subordinated to ideological comfort.

Conclusion: Education, Freedom, and the Courage to Question

The life of Albert Einstein demonstrates that intellectual freedom often emerges in opposition to institutions designed to cultivate it. His struggles within formal education were not failures of ability but indictments of systems that confused obedience with understanding. From early childhood anxieties through disciplinary conflict and eventual withdrawal from school, Einstein’s development reveals how institutional rigidity can misread and suppress unconventional intelligence. Education, as he experienced it, became an obstacle to learning rather than its conduit.

Einstein’s rejection of authoritarian schooling and dogmatic religion arose from the same epistemological commitment: the refusal to accept claims that could not withstand rational scrutiny. In both domains, authority demanded submission without explanation, while Einstein demanded coherence and evidence. Science offered a disciplined alternative, one that preserved awe without illusion and meaning without commandment. Through scientific inquiry, he found a framework that honored questioning as a moral virtue rather than a transgression.

This convergence of education and belief carries enduring relevance. Einstein’s life challenges contemporary educational models that prioritize standardized performance over conceptual depth and compliance over curiosity. It also unsettles religious frameworks that equate doubt with moral failure. His example suggests that genuine understanding requires environments that tolerate uncertainty and encourage exploration, even when such exploration destabilizes inherited structures.

Ultimately, Einstein’s legacy is not merely scientific but philosophical. He embodies the courage to question institutions that mistake authority for truth and tradition for wisdom. Education, in his life, became a practice of freedom rather than conformity, and spirituality became reverence grounded in understanding rather than belief. His story affirms that the pursuit of knowledge, when guided by intellectual honesty and independence, can serve as both an educational and ethical ideal.

Bibliography

- Einstein, Albert. Ideas and Opinions. New York: Crown Publishers, 1954.

- Ferré, Frederick. “Einstein on Religion and Science.” American Journal of Theology & Philosophy 1:1 (1980): 21-28.

- Fölsing, Albrecht. Albert Einstein: A Biography. New York: Viking, 1997.

- Hayes, Denis. “What Einstein Can Teach Us about Education.” International Journal of Primary, Elementary and Early Years Education 35:2 (2007): 143-154.

- Holton, Gerald. Thematic Origins of Scientific Thought. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1973.

- Isaacson, Walter. Einstein: His Life and Universe. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007.

- Jammer, Max. Einstein and Religion: Physics and Theology. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995.

- Pais, Abraham. Subtle Is the Lord: The Science and the Life of Albert Einstein. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982.

- Pyenson, Lewis. The Young Einstein: The Advent of Relativity. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1985.

- Spinoza, Baruch. Ethics. Various translated editions.

- Stachel, John. Einstein from “B” to “Z”. Boston: Birkhäuser, 2002.

Originally published by Brewminate, 01.14.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.