Interpretation of both the archaeological finds and the descriptions found in the written sources.

By Dr. Cecilie Brøns

Senior Researcher, Ancient Art

Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

Abstract

Golden textiles1 were significant across the ancient Mediterranean from the Archaic period (or perhaps even earlier) to Late Antiquity, i.e. from the 5th century BCE to the 5th century CE. By comparing and contrasting three primary sources – iconography, archaeological material and written sources (both literary and epigraphic)– this paper shows that the use of such extravagant textiles was far more extensive than previously assumed. Furthermore, as this paper will demonstrate, the images, particularly those found in iconography, offer compelling information about how these garments actually looked and were worn (and by whom), leading to a significantly better understanding of ancient garments and their versatility. This enhances the interpretation of both the archaeological finds and the descriptions found in the written sources.

Introduction

Gold is a precious metal. Its chemical symbol, Au, is derived from the Latin aurum, meaning gold. It has been used since antiquity in the production of jewellery, coinage, figurines and vessels as well as for the decoration of buildings, monuments, furniture and statues. It was also used in the ancient Mediterranean for textiles, either woven into garments or for their decoration. Though not uncommon, the practice of using expensive gold thread to embellish textiles was reserved for textiles belonging to people from the highest social strata. The manufacture of gold thread began very early: there is mention of golden textiles in the Old Testament,2 though they appear to have become especially popular during and after the collapse of the Roman Empire in the 5th century CE. Although evidence for these textiles exists in antiquity, there is still little known about them or how they looked. This paper therefore aims for the first time to develop new insights into their use from the 5th century BCE to the 5th century CE. It does so by investigating and collating three primary sources of evidence: iconography; the textiles found in archaeological contexts; and written sources both literary and epigraphic. These three sources offer different insights into the use of gold in textiles. The archaeological record sheds important light on the different techniques used in textile production; the written evidence, particularly from the Roman period, confirms their existence and demonstrates that they were primarily worn by Roman emperors and empresses. However, neither archaeology nor the written word can provide specific information about their use and appearance, and it is here that ancient iconography comes into its own by providing insights unavailable from other sources.

Iconography is, in fact, an overlooked but invaluable source of evidence in the study not only of golden textiles but of coloured textiles in general. Indeed, a closer examination of the polychrome decoration of sculptures, figurines and reliefs can provide unique insights into both the use of gold in textiles and their various colours and decoration. Thus, the many depictions of garments in various media, such as reliefs, figurines, sculpture, wall-paintings and mosaics, sometimes include depictions of what ought to be interpreted as golden textiles. Although the original colours of many of these depictions no longer survive, new advances in polychromy research can provide insights into their original colours and decoration.

Through combining these three sources of evidence, iconography, the textiles from archaeological discoveries and written sources, this paper will argue that golden textiles were not only present in antiquity from around 500 BCE–500 CE, but also formed a more significant aspect of the wardrobe of high-status men and women than hitherto thought. Moreover, this paper reveals how the images found in iconography offer compelling evidence about the way these garments actually looked and were worn, and by whom. This leads to a significantly better understanding of ancient garments and their versatility. Likewise, it will help in the interpretation of both the archaeological finds and the descriptions found in the written sources.

Golden Garments in Art: Ancient Polychromy3

Overview

Ancient iconography is the only source that can provide solid evidence as to the original appearance of these garments. Iconographic sources are of course not without their attendant problems and pitfalls, including the question whether these images illustrate either ‘real’ or ‘imaginary’ dress. How far, for example, do the images of clothed men and women from ancient Greece and Rome truly represent the clothes that men and women wore in real life? Do they instead depict an idealised version of Greco-Roman dress? Furthermore, although plenty of garments exist in both wall-paintings and vase paintings, these depictions seldom reveal whether the decoration shows the use of true gold or ‘simply’ a woven or embroidered decoration in fibres dyed to look like gold. A famous example of this is the wall-painting in the Franҫois tomb at Vulci, where Vel Saties is displayed in a mantle thought to be a toga picta (a ceremonial toga usually worn by triumphant generals after victorious campaigns) with figured decoration. However, although written sources indicate that the toga picta was embroidered with gold, it is impossible to tell from the depiction in question whether this was indeed the case.4

However, depictions in other media can help to establish the true appearance of golden textiles. Thus, ancient art works, such as marble sculptures, can provide important information about the original appearance of ancient garments even though most marble sculptures exhibited in museum collections around the globe appear to be entirely white. These sculptures were, however, originally painted with a bright arrangement of colours to make them appear as life-like as possible. Regrettably, most surviving pieces have lost their colours primarily because of poor preservation conditions, exposure to light and radiation, the fragility of the paint and, not least, the cleaning methods applied before or after the artefacts entered the museum (or private) collection.5 Nevertheless, although traces of the original polychromy are typically microscopic in size and very fragile, more advanced analytical methods, particularly in the natural sciences, can add new knowledge, for example by making it possible to identify pigments, binding agents, painting techniques and provenance. Modern polychromy research has thus become a highly interdisciplinary endeavour, involving archaeologists, conservators, chemists, physicists, geo-chemists and geologists, among others.

An operating microscope6 is a useful tool for identifying the use of even minuscule remains of gold. Microscopy can be supplemented with X-ray fluorescence (XRF), an extremely important analytical method in the research of colour. This can be carried out with a handheld apparatus, is non-invasive and does not damage the objects examined. XRF is also used to identify elements and is particularly suited to the analysis of inorganic pigments as well as metals, including gold.

‘Fake Gold’

Golden textiles were not only made using real gold but also with ‘fake’ gold pigment. Ancient painters, for example, employed the natural pigment orpiment, a canary-yellow sulphide of arsenic (As2S3) containing 60% arsenic, which produced a splendid and brilliant shade of yellow.7 The name ‘orpiment’ is derived from the Latin auripigmentum, literally ‘gold pigment’ from aurum (‘gold’) and pigmentum (‘pigment’), confirming its use as a substitute for gold in ancient polychromy. It is mentioned by ancient authors such as Pliny who records the following:

There is also one other method of procuring gold; by making it from orpiment, a mineral dug from the surface of the earth in Syria and much used by painters. It is just the colour of gold, but brittle, like mirror-stone, in fact. This substance greatly excited the hopes of the Emperor Caius, a prince who was most greedy for gold. He accordingly had a large quantity of it melted, and really did obtain some excellent gold; but then the proportion was so extremely small that he found himself a loser thereby. Such was the result of an experiment prompted solely by avarice: and this too, although the price of the orpiment itself was no more than four denarii per pound. Since his time, the experiment has never been repeated.8

Orpiment had been used since ancient times as a pigment in painting and for polychrome sculpture, even though it was not permanent and was toxic. There is also evidence for its use in polychromy from Middle and New Kingdom Egypt (16th–11th centuries BCE) where it was found in the painted decoration of wooden coffins and stelae.9 Later examples include a marble pyxis10 in the National Archaeological Museum of Athens. The pyxisis dated to the second half of the 5th century BCE and bears a battle scene with two polychrome chariots and charioteers fighting against two armed warriors. Orpiment was identified in its decoration, together with hematite (red) and goethite (yellow), cinnabar and lapis lazuli.11 So far, however, the use of orpiment to represent garments in ancient polychromy has not been identified, a situation which may quickly change as more ancient polychrome artefacts are examined.

Ancient Gilding Techniques

Gilding with gold leaf or foil was used on artefacts made out of different materials, including stone, terracotta, stucco and bronze.12 The earliest form of gilding was fire-gilding, whereby a layer of gold was applied to the surface of a less rare metal, a technique that goes back to the 3rd millennium BCE.13 However, the most common method of gilding during antiquity was the bolus technique (also known as ‘bole’ technique), whereby the gold leaf was usually applied onto a preparatory layer of very refined fine clayish earth pigment (bolus) in different colours (often red, orange or yellow),14 using an adhesive such as an animal or vegetable glue. Since these organic glues have degraded with time, the gilding has often disappeared, leaving only tiny remains on surfaces, particularly in folds and crevices.15 The red or yellow preparatory layers are now often the only surviving evidence (if any) of former gilding.16 Gilding is mentioned by Pliny (NH 33.20) who described how gilding was applied to marble with egg white, and to wood with a glutinous composition known as leucophoron.

The Grave Monument of Phrasikleia

The grave statue of Phrasikleia, dated to 520 BCE, provides an example of the use of gilding in the iconography of ancient textiles.17 This statue shows a standing young woman (a kore)18 dressed in a richly ornamented garment; on the skin and garment are numerous traces of polychromy. Analysis of this polychromy has revealed the use of red and yellow ochres, lead white, brown madder, vine black and orpiment.19 Red and yellow ochre and orpiment were used for her dress, while the rosettes and shining yellow swastikas scattered over the garment were painted with orpiment and yellow ochre. Moreover, gold leaf (and lead tin foil) was applied to her garment and jewellery, as well as possibly her belt.20 The gold leaf and the use of orpiment to create a ‘fake gold’ was meant to imitate gold ornaments sewn onto the garment. Parallels for such textile ornaments, often in the shape of roundels decorated with rosettes, are found in the archaeological record, primarily in burial contexts such as in the tomb of the ‘Lady of Archontiko’ at Pella (c.540–530 BCE). Here three gold rosettes and four plaques shaped like double triangles were recovered on the upper part of the torso, three rosettes on the abdomen and a silver plaque and two gold plaques with vegetal decoration and two small gold rosettes on the thighs. Finally, two small gold rosettes were found near her feet, probably originally intended to adorn her shoes.21 Gold rosettes and decorated plaques were also found in contexts that date from the Hellenistic Period.22

Tanagra Figurines

The Greek Tanagra terracotta figurines provide rich evidence about the colours of ancient dress because their polychromy is often relatively well preserved and sometimes includes gilding.

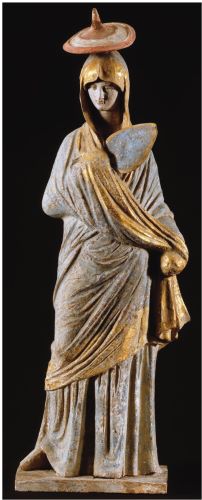

A terracotta figurine discovered in the collections of the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek provides a particularly interesting example of the use of gilding on clothing. This figurine of a standing woman, dated to the 3rd century BCE, is unfortunately of unknown provenance but clearly belongs to the well-known group of figurines from Tanagra (Fig. 9.1).23 It was previously suspected of being a forgery24 but recent analysis of its polychromy has identified the use of ancient pigments, including Egyptian blue, and painting tech-niques, which has ruled out the possibility of a modern manufacture.25

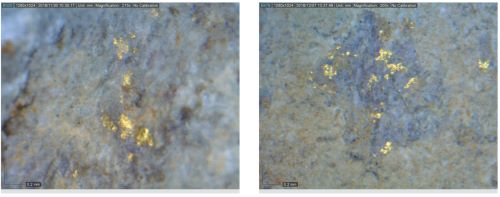

The figurine is shown wearing a chiton (a form of tunic made from two large rectangles sewn up the sides) of various colours. The polychromy is degraded and it is therefore difficult to interpret the decoration. Microscopic examination reveals the use of pink, purple and blue colours superimposed upon each other. In addition, the chiton has white horizontal decoration (in stripes?) in a rectangular area on its front. Lastly, gilding is used for a horizontal gold border at the lower edge of the chiton (Fig. 9.2.a) and perhaps also in other scattered traces of what may originally have been vertical stripes or scattered decoration.

On top of the chiton, the figurine wears a himation26 (a mantle or wrap) with a broad purple border and a narrower gilded border near the garment’s edge (Fig. 9.2.b). The colour of the remaining part of the himation cannot be determined without further analysis.

This figurine illustrates the rich and varied ways that gold might be used for textiles: the borders of himatia and chitones, as well as further decoration (in this case, of the chiton) which might represent gold weaving or embroidery. Furthermore, this example is a reminder that figurines, which at first glance appear to be ‘simply’ painted, could also include gilding, which is sometimes only preserved in the minutest of traces.

Garments embellished with gold have been recovered on other Tanagra figurines of standing women. The most significant example is the so-called ‘Lady in Blue Group’. This group consists of four figurines recovered from a tomb near Tanagra and dated to c. 330–300 BCE. After their discovery, they were divided between the Louvre,27 the British Museum,28 Staatliche Museen Berlin29 and the Hermitage.30 The figurines all wear similar garments in similar colours. Those in the Louvre and in Berlin wear a blue chiton underneath a himation with a broad gilded border (Fig. 9.3. a–b).31 The polychromy of the Hermitage figurine differs in terms of the gilding which covers a large part of the himation instead of being used to emphasise the border. Thus the figurine is represented in a blue chiton with a white rectangle and a gilded himation with a blue border. Except for the figurine in the British Museum, all the ones in this group are embellished with a considerable amount of gilding in contrast to the other Tanagra figurines where the gilding (if deemed to have been present) was often limited to the figurine’s accessories.32

Examinations of Tanagra figurines in the Louvre, including the ‘Lady in Blue’, have shown that the gilding was often carried out with the ‘bolus’ (bole) technique, described above.33 In the case of the ‘Lady in Blue’, this was supplemented by the additional refinement of burnishing. On the wide gilded band decorating the himation, the gold has an extraordinary glow to it, a finish obviously achieved by polishing with a hard stone. The gold leaf has been applied to a ground of fine-grained yellow ochre.34 In all the Tanagra figurines, the gilding method used was gold on bolus, the gold leaf being made from fine gold (99.9%) which was first applied onto a thin layer of yellow ochre containing goethite before being burnished with a tool.35 In no instance was there any trace of orpiment on the figurines studied.36

These examples illustrate the varied ways in which gold could be used for ancient textiles: primarily for borders of himatia and chitones but also for the main part of himatia, as well as for the additional decoration of chitones. It seems that precious materials such as gold leaf could also be used on relatively cheap objects such as terracottas.

Greco-Roman Marble Sculpture

Greco-Roman marble sculpture provides further important information about the iconographic record of gilded garments even though gilding on Roman marble statuary has generally been viewed as a decorative embellishment of limited value.37 The following section shows this not to be the case.38 As with the terracotta figurines, interpreting the use of gold in iconography can be problematic, most importantly because gilding is used in ways that do not reflect reality such as in portraying highlights in hair, accessories and even skin, as well as in representing textiles. Nevertheless, other examples exist where gilding has clearly been used for the embellishment of sculpted garments, thus leaving no doubt that it represents golden textiles.

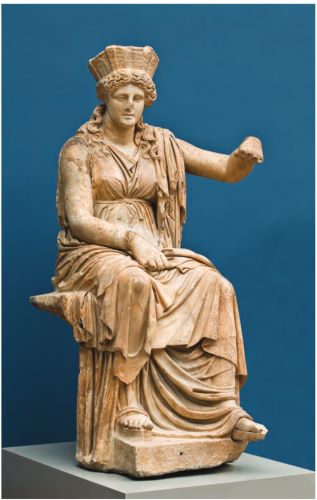

A somewhat surprising example of this practice is the seated statue of the goddess Kybele in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek (Fig. 9.4).39 This statue was recovered in a sanctuary at Formiae, Italy and has been dated to c. 60 BCE.

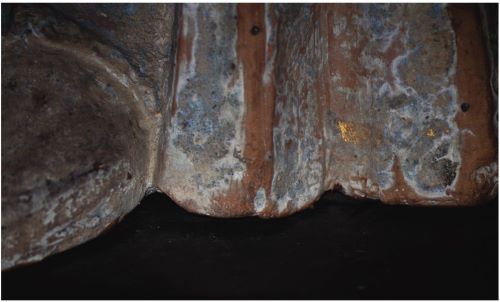

It was recently examined thoroughly and its traces of polychromy were extensively analysed.40 Besides a wealth of polychromy in pinks, purples and blues on her garments, the analyses revealed minute traces of gilding on the border and tassels of her mantle (Fig. 9.5). It has now been established that the statue was originally made wearing a heavily decorated costume with gilded ornamentation.

Another Roman example is a colossal statue of a naked male from the Hadrianic Baths at Aphrodisias who probably represents the hero Achilles. The statue is shown wearing a massive hanging chlamys (a type of ancient Greek cloak) which preserves faint, but extensive, vestiges of the red pigment cinnabar. Furthermore, a fragmentary white calcium carbonate ground on the garment’s border, topped with yellow and red ochre, was presumed to have been gilded.41

There are also several examples of gilding on Delian sculptures, most likely due to the large number of sculptures and figurines examined from this particular site.42 The bole technique is once again encountered on gilding used on the Delian marble and terracotta artefacts. This technique involves sticking very thin gold leaf onto a coloured ground made of ochre which on Delos is usually a fine yellow ochre. Beneath this preparatory layer, a thin foundation layer of fine-grained white compound has been applied onto the marble substrate.43

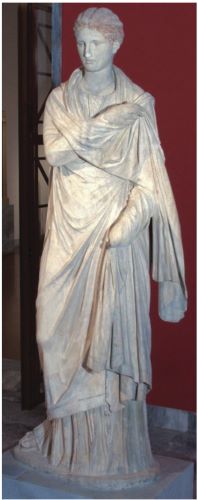

A further example of the use of polychromy and gilding for replicating garments on a marble statue is the so-called ‘Small Herculaneum Woman’, dated to the 2nd century BCE (Fig. 9.6).44 The polychromy of the sculpted garments in this example is exceptionally well preserved, showing rich ornamentation: the chiton has two parallel dark blue bands along the hem and two vertical bands with wavy edges on the left side of the garment. The himation is decorated with a dark blue border with radiating lines.

In addition, the edge of the short side of the himation is bordered by a golden band on top of a violet layer (Fig. 9.7).45 Another Delian example is a statue of Apollo excavated at the House of the Masks.46 The chlamys worn by the statue was embellished with a gilded border on top of a layer of brown ochre.47

A final Delian example is a headless female marble statuette, dated to around the end of the 2nd or the beginning of the 1st century BCE and recovered from the House of the Masks on Delos.48 The entire garments of this piece, and not just the gilded border, were originally gilded. The statue has retained minute traces of shiny fragments of the gold leaf on top of a ground of yellow ochre. The gold leaf is made of purified gold (c. 96%) and is c. 4 to 5 microns thick.49

Furthermore, metal attachments, either in gold, silver or bronze, were used to add dress and accessory details. These have usually now disappeared, but drill holes for their attachment provide evidence of their original existence. There are plenty of examples of sculptures with such drill holes from antiquity.50 One is the marble sculpture of a running Niobid from the Gardens of Sallust, dated to c. 440–30 BCE.51 The sculpture has drill holes in the hair, possibly for the attachment of a hairband (or extra curls), as well as holes for the attachment of a belt – perhaps in gold.

Besides testifying to the ancient skill in painting and gilding marble artefacts, this survey illustrates the portrayal of golden textiles for male as well as female sculptures, primarily in the form of gilded borders but also for entirely gilded mantles. Although factors such as weathering have unfortunately often reduced the gilding to micro-particles which are hardly detectable, even at high magnification, careful analyses of the artefacts and knowledge of ancient polychromy can reveal the original gilding. It is more than likely that future investigations will reveal many more representations of golden garments in the extant record of ancient marble statuary.

Mosaics

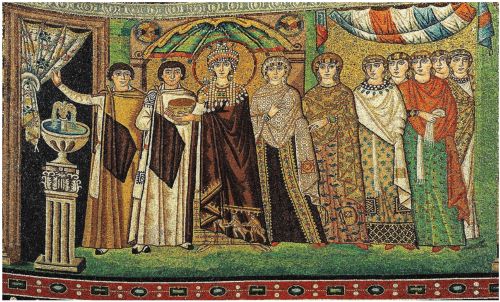

A final art form which should be mentioned in connection with the gilding tradition is mosaic. Mosaics provide a rich source of knowledge about ancient dress. Although it is impossible to tell from most mosaics whether garments are ornamented with gold, there are some exceptions. One is the mosaics of the Emperor Justinian and Empress Theodora at the Church of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy (c. 547 CE), which include tesserae of gold. One of these mosaics shows Empress Theodora draped in a royal purple chlamys over an embroidered gown (Fig. 9.8). The bottom edge of her chlamys features a tapestry-woven depiction of what are probably the three magi bearing gifts. This decoration almost certainly represents an actual tapestry woven with gold thread.

Archaeological Evidence

To what extent, then, are the iconographic representations of golden textiles supported by the archaeological record? Fragments of gold textiles, similar to those depicted in iconography, have been recovered from all over the Mediterranean littoral, often in the form of tiny fragments of gold thread. Although at first glance the archaeological material might seem sparse, a survey published in 2008 by Margarita Gleba showed that golden textiles have been recovered in a wide range of countries, including Spain, France, Italy, Greece, Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Egypt, Ukraine and southern Russia.52 The earliest finds so far from Greece date to the Classical period, while in Italy some fragments of gold thread and textiles date back to around the 7th century BCE.53 Most of these finds are primarily – if not exclusively – from burials,54 which may create a certain bias in that such garments may not necessarily represent the type of garments worn in real life.

The majority of these archaeological finds consist of gold threads which provide little information about the types of garments they belonged to or what they looked like. Nevertheless, they can provide insights into the different ways that gold could be used with textiles.55 The archaeological evidence thus suggests that gold could be: woven alone; interwoven with other material (for example simply woven into or incorporated within the tapestry); or used for embroidery and other types of applied decoration.56 It could also be used by itself to create hairnets using sprang technique (similar to plaiting) or to make cords, fillets or fringes.57

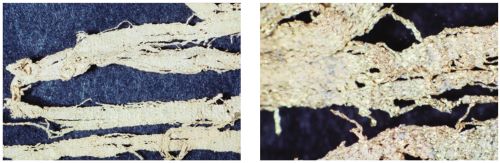

There are several examples of the first type of woven golden textiles in the archaeological record. Examples of golden textiles, woven without other types of material, include the minuscule fragments that were found in a glass urn containing burnt bones recovered in a grave in southern Italy. The urn belongs to a type known to have been popular from the middle of the 1st century CE to the middle of the 2nd century CE, which gives an approximate date for the textile. The fragments are woven. Each thread is c.2mm wide and 17–26 mm long and wound Z-wise around a fibrous core which has now disintegrated. The weave has c. 12–15 threads per mm (Fig. 9.9).58 Other examples, not included in Gleba’s article, are the fragments of gold textiles recovered in a sarcophagus from the 2nd century CE at Paphos, Cyprus. These fragments consist of a very fine flat ribbon of gold twisted around a core thread of purple/reddish silk. Up to ten small sections of woven golden fabric were found still intact, each of which was no more than 15 mm × 10 mm. The threads themselves are tiny, no more than 1 mm long.59

A further hitherto unpublished example is a group of 56 tiny woven gold textile and cord fragments, preserved in the collections of the J. Paul Getty Museum. Most of these fragmented remains consist of small sections of primarily weft-faced tabby60 textile that is fashioned from tiny strip-twisted gold wires (approximately 0.10 mm in diameter). The sturdiest mesh samples (1.4 cm wide) retain selvages on both sides (some with folds and seams). An analysis of its composition has allowed certain fragments to be paired one to another end-to-end to make sections of a fillet, or vitta, originally measuring nearly a metre in length.61 There is no evidence of a fibre core. This is significant, since the gold threads used for such textiles (whether exclusively in gold or interwoven with other material) were usually either made by twisting gold wire or gold strips around a fibre core (silk, wool, vegetal fibre or animal gut),62 or by using so-called lamellae made from hammered gold foil cut into fine strips.63

Many of the preserved gold-woven textiles appear to have been ribbons, fillets, applied borders and the like, which is perhaps not surprising due to their cost, rigidity and heaviness which would have made them a difficult material to use for entire garments. Further examples of such pieces include a large fragment of a ribbon woven with gold thread, recovered in a barrel vault (number 5) of the ancient port of Roman Herculaneum.64 Similarly, strips of golden weft have been found in burials at Taranto which have been dated to the 4th to 1st centuries BCE. Different types of golden textiles, such as ribbons, cords and hairnets, have also been recovered from burials in Rome and its surrounding areas.65

According to Gleba, the second category, that of gold woven into fabric, was more common. Rather than being woven alone, gold was frequently interwoven with other material, primarily purple wool and silk, a practice that became particularly prevalent during the Hellenistic period.66 The most magnificent example of such a textile of gold interwoven with yarn comes from the so-called Tomb of Philip II in Vergina Greece, dated to the 4th century BCE. In a gold larnax (a small closed coffin or urn), two rectangular pieces of textile woven in gold and purple tapestry have been recovered together with the cremated remains of a woman. Unfortunately, the warp threads have disintegrated, making it impossible to determine the structure.67 A further example is the group of textile fragments recovered inside a sarcophagus in the eastern cemetery of Thessaloniki (Greece). The burial contained the remains of a woman and has been dated to the 4th century CE.68 This find consists of six pieces of tapestry-woven textile with plant motifs and with threads consisting of gold strips wrapped around a core of purple silk thread. Two of the pieces are L-shaped and the rest approximately rectangular. According to Tzanavari, the preserved pieces are relatively small and unconnected to each other, which indicates that they are strips sewn onto the garment.69 One final example of interwoven gold textiles given here is that of the remains of fine woollen threads, wrapped in gold foil, which were recovered in the sarcophagus of Philotera from Kerameikos, dated to the 3rd century CE.70

Embroidery and other types of applied decoration provide the third type of golden textiles found in archaeological settings. Embroidered textiles, however, are rare in the Mediterranean area.71 One example is a fragment of a linen balanced tabby (plain weave) preserved in a bronze urn found at Koropi near Athens. It dates to the late 5th century BCE. The embroidery has been done with linen threads wound about with metal foil – probably silver – to create a lozenge-shaped pattern with small lions in the centre, though only the holes are now visible.72 Fragments of gold embroidery have also been recovered in Rome in a tomb at the Via dei Granai di Nerva, dated to the 2nd century CE.73

These examples demonstrate the different uses of, and techniques applied to, golden textiles in antiquity. Their state of preservation, however, is often extremely poor, making it impossible to decipher their original appearance or the type of garment or accessory for which they were used. However, as demonstrated above, many of the archaeological finds appear to have been ribbons or fillets, possibly used as decorative borders on garments or as belts, girdles or hairbands. This supports the iconographic evidence which particularly highlights the use of garments with golden borders. Moreover, the many examples of holes for metal attachments provide evidence for the use of metal belts and hair bands. The presence of tapestry-woven golden textiles is also evident in the iconography, either in woven borders on mantles and tunics or for entire garments, such as the Tanagra figurine with a golden himation. The archaeological source material therefore not only corroborates the evidence from iconographic sources but also adds specific information about how these garments were originally produced.

Written Sources

Overview

Garments made with gold are referred to in a wealth of ancient literary sources from all over the Mediterranean littoral. The Old Testament provides some of the earliest textual evidence for the existence of gold: the ephod (a ceremonial dress) made for Aaron is described as follows (Exodus 39.3):

He made the ephod of gold, and of blue and purple and scarlet material, and fine twisted linen. Then they hammered out gold sheets and cut them into threads to be woven in with the blue and the purple and the scarlet material.

Similarly in Psalm 45.13, the king’s daughter’s clothing is described as being interwoven with gold.

Although written sources provide a wealth of information on ancient textiles, their historical accuracy has sometimes to be questioned because some of the translators had little specialist understanding of ancient garments and their manufacture. During the 19th and 20th centuries, when many of these translations were completed, they were done by men who often lacked a specific knowledge of textile work. Most garment terms are thus simply translated as ‘robe’, ‘cloak’ or ‘tunic’. Descriptions of the decoration and method of production can also become distorted. There is a tendency, it seems, to translate many of these terms as ‘embroidery’ (the Greek chrysopoikilos) or ‘shot with gold’ (the Greek chrysopastos).74 In most instances, it is therefore impossible to tell whether the garments described in these sources were decorated by means of embroidery, tapestry technique or some other form of decoration; or even, in other instances, whether the entire garment was woven in gold or made from a combination of gold and organic fibre thread. Such broad-brush translations obscure the important nuances and meanings reflected by particular choices of terminology and even risk creating a distorted understanding of these tex-tiles.75 Examples of a range of written references to golden textiles are given below.

Greek Epigraphy: Golden Textiles for the Gods

Among the written evidence for golden textiles are the so-called temple inventories which are lists recording votive offerings that were kept in the temple treasuries in certain Greek sanctuaries.76 They generally date from the 5th BCE to the 2nd century CE.77 Golden textiles are hard to detect in the inventories, though they may be represented in garments described as chrysopoikilos. This term is usually translated as ‘gold-embroidered’, but it might equally refer to gold that has been woven into the fabric in question.78 The term is only recorded in an inventory from Miletos where it denotes a strophion79 with a thunderbolt motif designated as chrysopoikilos. Another inventory from Samos records a chitoniskos which is described as chrysoi peripoikilmenos, a variant of peripoikilos which can perhaps be translated as ‘interwoven with gold’ or ‘decorated with gold all over’, possibly reflecting the technique of weaving in gold. The term diachrysos, typically translated as ‘interwoven with gold’,80 is only recorded on Delos where it is used to describe a belt/girdle.

The inventories also record the use of attachments to decorate the textiles. For example, the term pasmatia, interpreted as metal ornaments sewn into garments, provides evidence of this practice.81 Other possible terms include: epichrysos, meaning ‘overlaid/plaited with gold’ or, sometimes, indicative of metal decorations on garments;82 and epitektos, meaning ‘overlaid with gold’ or ‘with gold ornaments’.83 All three terms are used in the Brauron catalogues in relation to garments (poikilen, trichapton, kandys). The inventories from Brauron specify pasmatia overlaid with gold (epitekta)84 and pasmatia of gold (chrysa).85 The former is placed on the garment ‘along the border’.86 The inventory from Miletos records a kalasiris with a gold border (perichrysos), two strophoi and a woollen belt/girdle overlaid or plaited with gold (epichrysos); and at Delos, in the Artemision, the goddess is clothed in a purple garment (estheta porphyran), again overlaid or plaited with gold (epichrysos).87 These particular terms (perichrysos and epichrysos) do not occur in the inventories from Brauron or elsewhere.

It is important to note that the garments recorded in the inventories were donated as votive offerings, primarily to female goddesses; and that they were sometimes even used to dress the cult images. They do not necessarily, therefore, reflect the everyday clothing worn by ‘real’ people; instead, they may represent rather special garments, created for a specific purpose, similar to funerary garments.

Latin Sources

Latin sources have plenty to say about different garments of gold. The Historia Augusta (SHA), written in the 4th century CE, is a particularly rich source for how Roman emperors and empresses wore these textiles. However, it should be noted that the SHA is a highly problematic text rather than a serious biography or history; it uses descriptions of dress to create positive, or negative, images of individual emperors, thereby categorising the characters of the emperors according to what they wore.88 The text is perhaps best used to demonstrate the existence of golden garments (at least from the 4th century CE) and their preciousness, rather than whether or not the emperor in question ever wore them.

The SHA, for example, describes how Marcus Aurelius, regarded as a ‘good’ emperor, ‘held a public sale in the Forum of the Deified Trajan of the imperial furnishings, and sold … his wife’s silken gold-embroidered robes’ (or perhaps ‘garments of silk and gold’).89 Golden garments are also mentioned in relation to Pertinax who held a sale of Commodus’ belongings on his accession, which included robes of silk foundation with gold work of remarkable work-manship;90 and to Elagabalus, who is described as wearing a tunic of gold cloth, or a Persian tunic studded with jewels.91 For the wedding of Maximinus the Younger, the betrothal gifts included garments that were worked with gold.92 As a final example, it is stated that Aurelian intended to forbid the use of gold in ceilings, tunics and leather.93

Other Roman authors also mention the use of golden garments for the Imperial families, for example Tacitus, according to whom Agrippina the Younger, the wife of Claudius, once wore a mantle made entirely of gold while watching a mock naval battle.94 Suetonius describes the burial of Nero who was laid on a bier which was covered with white robes, interwoven with gold, which he had previously worn.95

The high status of golden textiles is also reflected in descriptions found in Latin poetry. Vergil mentions golden textiles several times, for example in the Aeneid, where Andromache brings a garment (vestes) decorated (embroidered or woven) in gold as a present for Ascanius.96 In Book 1, he mentions that gifts saved from the ruins of Troy included a garment (palla) that is stiff with golden decoration;97 and in Book 11, Chloreus, the priest of Cybele, wears precious, yellow garments of gold and linen.98 Golden garments are also mentioned in the Georgics as being a sign of wealth and prosperity.99

Ovid is another Latin author who often describes golden garments. In the story of Pentheus and Bacchus, the god is adorned with ‘embroidered robes of interwoven gold’.100 in his story about Arachne and Minerva he describes textiles of a ‘scintillating beauty to the sight of all who gaze upon it; so the threads, inwoven, mingled in a thousand tints, harmonious and contrasting; shot with gold: and there, depicted in those shining webs, were shown the histories of ancient days’.101 In the story of Aglauros and Mercury, Mercury is dressed in a flowing garment with a fringe of radiant gold.102 Some women also wear golden garments, for example Niobe wears a purple garment, bright with in-woven threads of yellow gold;103 and Procne has a royal robe bordered with the purest gold which she puts away in order to don garments of mourning.104 In Book 9, the poet mentions the Amazonian girdle wrought of gold.105

Although these examples are not exhaustive,106 they give a vivid indication of how familiar golden garments would have been to a Roman audience. However, neither the evidence from poetry nor ‘historic’ sources such as the SHA can provide any real evidence as to how widespread or common these textiles were or what they looked like and how they were made. Instead, poetry and other written sources potentially offer a distorted or biased image of ancient dress that illustrates either the divine or high status of the individual wearing them; or specific moral values or societal ideals. Moreover, the descriptions of these garments are usually vague and limited to the fact that gold is included in their decoration, whether it be interwoven, possibly in tapestry, or applied as decoration. Yet some examples appear specifically to mention garments with gold borders as the ones depicted in art and probably represented in the archaeological record. Moreover, the SHA mentions that Agrippina the Younger wore a mantle made entirely of gold, perhaps similar to the one represented on the Tanagra figurine from the Hermitage, described above.

Roman Epigraphy: The Producers of Golden Textiles

Golden textiles are also referred to in Roman funerary epigraphy. However, the Latin inscriptions refer only to their producers and not to the golden textiles themselves or their appearance. Two funerary inscriptions from Rome mention the women who produced such textiles. The first is found on a marble olla (cooking pot) from the 1st century CE, from the Via Sacra, which commemorates a woman named Sellia Epyre. This woman is described as an aurivestrix,which has been interpreted as a dressmaker in gold.107 The second is on a marble slab, dated to the end of the 3rd or beginning of the 4th century CE, commemorating a young girl named Viccentia who died at the age of 9 years and 9 months. The inscription describes her as aurinetrix – a spinner of gold thread.108 However, both terms are only found once so it is impossible to say how common these job titles might have been.

Other inscriptions mention Attalica, a term which can be translated as gold-cloth either embroidered or woven.109 This interpretation is based on Pliny’s statements. He writes:

‘King Attalus, who also lived in Asia, invented the art of embroidering with gold, from which these garments have been called Attalic’.110

The term is also mentioned by Propertius (3.18) who speaks of Attalicae vestes and by Varro (fr. 68).111 The term is found on two marble bases, dated to c. 18–12 BCE, which were recovered at the Via Ostiense in Rome.112

Furthermore, the term barbaricarius (pl. barbaricarii) is usually understood to refer to a maker of cloth with gold or silver threads or as denoting a gilder.113 Sinnigen thus interprets the barbaricarii as ‘workers who decorated parade armour with gold and silver and who produced brocades and fancy textiles in which those precious metals and gems were woven’.114 The term is mentioned in several inscriptions primarily from the 2nd to the 4th century CE115 and is listed among the textile professions in Diocletian’s price edict.116

These sources say nothing about the appearance or manufacture of golden textiles but they do show that textiles made entirely of gold or with gold were regularly produced during the Roman period, thus indicating a specialised craft. The existence of different designations or titles for the producers of gold textiles may reflect the production of distinct textile types.

It is also likely that producers of other types of textiles could also produce gold textiles alongside their main area of specialisation. As an example, a graffito in the officina coactiliaria of the felter M. Vecilius Verecundus of Pompeii mentions a tunica lintea aurata;117 this might indicate that golden textiles were somehow related to his workshop. Golden textiles might also have been produced by gold-smiths rather than by textile specialists. Thus, according to written sources, Demosthenes is thought to have had a special outfit made for the choregic procession (a procession to celebrate Athenian democracy) which included a gold-embroidered (?) himation prepared by a goldsmith in the agora.118 Finally, golden textiles might have been produced in private households by elite women for their own use. Claudian, for example, describes how the woman Probia makes golden cord by drawing out silk threads of equal length with the threads of gold and intertwining them.

Joy is in the heart of that aged mother whose skilled fingers now make ready gold-embroidered vestment and garments agleam with the thread which the Seres comb out from their delicate plants, gathering the leafy fleece of the wool-bearing trees. These long threads she draws out to an equal length with the threads of gold and by intertwining them makes one golden cord.

Translation: Platnauer 1922119

Furthermore, golden textiles would probably also have been imported from abroad, for instance from Phrygia, Lydia, Alexandria, Tyre or Taranto, and it is plausible that many places of production were active simultaneously.120 However, between the 4th and 6th centuries CE, the production of golden textiles appears to have become a monopoly of the Roman state, thereby excluding their production by private craftsmen or women.121

Conclusion

Golden textiles were clearly significant across the ancient Mediterranean from the Archaic period (or perhaps even earlier) to Late Antiquity, i.e. from the 5th century BCE to the 5th century CE. By comparing and contrasting three primary sources – iconography, archaeological material and written sources (both literary and epigraphic) – it appears that the use of such extravagant textiles was far more extensive than previously assumed. Gold was so often used for garments and accessories such as ribbons, fillets and belts that, notwithstanding its high value, it cannot have been a rare sight among the higher strata of ancient societies. It is furthermore not surprising that all primary sources confirm the high status of these garments; and that they were reserved for men and women of elite status such as divinities and, particularly, for the Roman Imperial family, all portrayed in artistic and written sources. It is noteworthy that there is as yet no evidence that children of high social status wore golden garments, but this may be because all the known iconographic examples with preserved gilding feature adults – and the archaeological material does not as yet include child burials.

Iconography, archaeological material and written sources serve different purposes and provide different data which can potentially supplement each other. Written sources, for example, mention garments that cannot (as yet) be identified in the archaeological record or in imagery. However, it is only iconography that can provide insights into how golden garments might have been assembled, draped and worn. Images can also provide more accurate information about how gilded figures might once have looked. The Tanagra figurines are an excellent example of this since they illustrate the various ways in which gold was used in ancient times, including differences in the golden borders used for both mantles and tunics. These borders could vary in width from narrow borders (the figurine from the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek) to very wide borders (the figurine from Berlin). Gold was not only used for borders, as the figurine from the Hermitage shows: it could also form the body of fabrics used for mantles and the like. Marble sculptures also shed valuable light on the use of gold in textile production since a wealth of information can be found in their polychromy and in the occasional holes made for metal attachments.

The study of ancient polychromy is still relatively new and has yet to be fully integrated into the study of ancient textiles. Archaeological discoveries in the future will no doubt provide new insights and flesh out the information gleaned from the careful examination of ancient art works. With this more nuanced picture will emerge a greater understanding of the fabrics of ancient societies, of dress and clothing in general and of the place within them of golden textiles. Polychromy studies will play a key part in this process, whether the evidence be archaeological, written or, most significantly, iconographic.

Appendix

Endnotes

- The term ‘Golden’ textiles, fabric or decoration is used in this article to signify textiles (or decoration) which have gold either woven by various methods into the fabric or used or added as decoration.

- Gleba (2008, 61); Exodus 39.3.

- The practice of painting sculpture etc. in a variety of colours.

- Livy, Ad Urbe Condita 10.7.9 and 30.15.11–12.

- Bourgeois (2010, 239).

- An operating microscope or surgical microscope is an optical microscope.

- Eastaugh et al. (2004, 285).

- Pliny 33:22; translation Bostock (1855). Orpiment is also mentioned by Vitruvius (7.7.5) who believed it came from Pontus, the ancient name of the north-eastern province of Asia Minor.

- Eastaugh et al. (2004, 285).

- Usually a cylindrical vessel used mainly by women to hold cosmetics, jewellery etc.

- Brecoulaki (2014).

- Zink (2019).

- Oddy (1981, 75).

- Zink (2019).

- Oddy (1981, 76–77).

- Zink (2019). For examples of bole gilding on red pigments on Roman marble statuary, see for example Abbe (2010, 280–284).

- National Archaeological Museum Athens, inv. no. 4889.

- Greek sing. kore, pl. korai.

- Brinkmann et al. (2017, 121).

- Brinkmann et al. (2017, 121).

- Chrysostomou and Chrysostomou (2012, 370, 378).

- Examples include Williams and Ogden (1994, 104); British Museum, inv. nos GR 1877.9–10.15, GR 1876.5–17.11; and Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, inv. nos 06.1217.4–10.

- Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, inv. no. IN 895. According to museum records, it was acquired in 1886 in Paris from the collections of H. Hoffmann. Height 40 cm.

- Nielsen and Østergaard (1997, 98).

- For the use of Egyptian blue as an indication of authenticity, see Brøns et al. (2018).

- Greek sing. himation, pl. himatia.

- Louvre, inv. no. MNB 907. Height 32.5 cm.

- British Museum, inv. no. 1875,1012.15. Height 24.2 cm. Pink himation and no traces of gilding.

- Antikensammlung, Berlin, inv. no. TC 7674. Height 34 cm.

- St Hermitage Museum, inv. no. 435A. Height 31 cm. Gilded himation with a blue border; blue chiton with a white rectangle (?); white shoes with red soles; fan with gilded border.

- Analysis of the polychromy of the Louvre figurine has identified a white preparation layer, covered by a grey layer of kaolin and carbon black, followed by a layer of Egyptian blue for the garments. See Bourgeois (2010) for a discussion.

- Jeammet (2010, 118).

- See also Mactaggart and Mactaggart (2011, 41–48).

- Bourgeois (2010, 240).

- Pagés-Camagna (2010, 251).

- Pagés-Camagna (2010, 250).

- Abbe (2010, 280).

- For entirely gilded sculptures, see Blume (2015, 104–106). An example is the Hellenistic statue group of Artemis and Iphigenia in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek where analysis has shown the entire sculpture of Artemis to have been originally gilded, inv. nos. IN 481–482. Note that there is no evidence gold use in cosmetics during antiquity. Orpiment, a yellow pigment imitating gold, was used only for hair removal. Stewart (2007, 93).

- Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, inv. no. IN 480. Height 172 cm.

- The analyses carried out by the conservator Signe Buccarella Hedegaard in 2018–2019.

- Abbe (2010, 284–285).

- Bourgeois and Jockey (2010).

- Bourgeois and Jockey (2010, 230).

- National Archaeological Museum of Athens, inv. no. 1827. Height 175 cm.

- Blume (2010, 247–250); Blume (2015, cat. 25); Bourgeois and Jockey (2010, 231). The basic colour(s) of the garments cannot be determined, although there are some traces of red on the chiton and pink on the himation. See Blume (2010, 247–250).

- Delos Museum, inv. no. A4135.

- Bourgeois and Jockey (2010, 230).

- Delos Museum, inv. no. A4134. Height 68 cm.

- Bourgeois and Jockey (2010, 230); Blume (2015, 205, cat.30).

- See for example Brøns (2014, 68–71).

- Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, inv. no. IN 520. Height: 140 cm. Ridgway (1981) suggests that the statue is a Roman copy of a Greek original. Vague traces of blue colour in the folds of her garment evident in 1936 are no longer visible.

- Gleba (2008). See also Bedini et al.’s (2004) study of golden textiles from Rome and its surroundings. Their incidence may be much higher since the organic components of the textiles, such as gold thread, are only rarely preserved; and even these may have been misidentified as jewellery, not textiles, in scholarly publications, See also Nosch (2016).

- For example, a funerary urn from Chianciano, dated to the 7th century BCE or earlier, contained fragments of a purple linen fabric mixed with bits of gold. Sebesta (2001, 66); Bonfante (2003, 11). In the Regoloni-Galassi tomb, first half of the 7th century BCE, were found the remnants of a woman’s robe, once heavily decorated with gold. Shams (1987, 12,14); Sebesta (2001, 66).

- Gleba (2008).

- Included here are only the significant examples of golden textiles and reports of new research not found in Gleba (2008).

- Gleba (2008, 68).

- For example Metropolitan Museum of Art, inv. no. 1987.220 (c. 200–150 BCE); Antikensammlung, Berlin, inv. no. 1980.22.

- National Museum of Denmark, inv. no. 848. Pers. comm., Bodil Bundgaard-Rasmussen.

- Garcia and Conroy (2010).

- A weft-faced tabby is a plain weave (tabby) textile with a predominant weft.

- Pers. comm., Mary Louise Hart; research to be published in a forthcoming Getty Research Journal. See also http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/15172/unknown-maker-textile-fragments-roman-100-bc-100-ad/ (accessed June2021).

- Gleba (2008, 68).

- Gold strips such as these, usually dating to the 4th century BCE, have for example been recovered from the Mausoleum at Halikarnassos. The lamellae, dated to the first half of the 4th century BCE, were found together with gold ornaments: appliques, rosettes and similar items. The lamellae, made of a gold foil hammered thin and cut into strips of 0.2 mm to 1mm wide, are preserved in lengths ranging from 0.6 to 7.9cm. Bundgaard-Rasmussen (1998); Jeppesen (2000, 124–140, nos 40, 48, 61, 66, 88).

- D’Orazio and Martuscelli (1999, 177, no. 202); Gleba (2008,65).

- Bedini et al. (2004).

- Gleba (2008, 61, 62).

- Gleba (2008, 65). Another example – a gold and purple linen cloth, decorated with vegetal motifs – was said to have been found in a tomb at Derveni, see Makaronas (1963).

- Tzanavari (2012, 25).

- Tzanavari (2012, 28).

- Touratsoglou (2011).

- Droß-Krüpe and Paetz gen. Schieck (2014, 219).

- Barber (1991, 206); Gleba (2008, 65); Droß-Krüpe and Paetz gen. Schieck (2014, 221).

- Bedini et al. (2004, 84).

- LSJ s.v. chrysopoikilos and chrysopastos.

- Brøns (2016, 15).

- Golden textiles were also donated in Roman sanctuaries: an inscription records a donation at Nemi of a purple linen tunic with gold clavi. CIL 14.2215: lentea purpura cum clavis aurea.

- For a thorough study of Greek temple inventory lists, see Brøns (2016).

- LSJ s.v. chrysopoikilos.

- The strophion is an elusive garment item, interpreted as a band worn by women around the chest or a headband worn by priests. LSJ s.v. strophion.

- LSJ s.v. diachrysos.

- Cleland et al. (2007, 139).

- Cleland et al. (2007, 59. LSJ s.v. epichrysos).

- Cleland et al. (2007, 59. LSJ s.v. epitēktos).

- IG II2 1524B, 178.

- IG II2 1523, 9 = IG II2 1524, 181.

- Linders (1972, 26).

- ID 1442B, 54–56.

- Harlow (2005, 152).

- SHA Marcus Aurelius 17.4: vestem uxoriam sericam et auratam. Translation: Magie (1921).

- SHA Pertinax 8.2–4: vestis subtegmine serico aureis filis insigni opere. Harlow (2005, 149).

- SHA Elag. 23.4. Harlow (2005, 147).

- SHA Maxim. Duo, 27.3–8: vestes auratas.

- SHA, Aur. 46.1. See also Tacitus 11.6, with Harlow (2005, 151).

- Tac. Ann. 12.56: chlamyde aurata, and cf. Sebesta (2001, 71–72).

- Suet. Ner. 6.50.

- Verg. Aen. 3.483: picturatas auri subtemine vestes.

- Verg. Aen. 1.648: pallam signis auroque rigentem.

- Verg. Aen. 11.776: tum croceam chlamydemque sinusque crepantis carbaseos fulvo in nodum collegerat auro pictus acu tunicas et barbara tegmina crurum.

- Verg. Georg. 2.464: auro vestes.

- Ov. Met. 3.509: coronae purpuraque et pictis intextum vestibus aurum.

- Ov. Met. 6.1. Translation: Brookes More (1922).

- Ov. Met. 2.708.

- Ov. Met. 6.146.

- Ov. Met. 6.504.

- Ov. Met. 9.172.

- Other examples include Apuleius (Golden Ass 4.7), Horace (Carm. 4.9.14: aurum vestibus inlitum), and Valerius Flaccus (3.11: muneribus primas coniunx Percosia vestes quas dabat et picto Clitevariaverat auro).

- Museo Nazionale Romano, inv. no. 29316. CIL 6.9214. See Chioffi (2004, 91–92).

- Musei Vaticani, Rome. CIL 6.9213. Chioffi (2004, 94).

- LSJ s.v. Attalicus. Attălĭca, ōrum, n. (sc. vestimenta), garments of inwoven gold.

- Plin. 8.74. Translation: Bostock (1855).

- Varro, fr. 68: From the Attalid legacy came tapestries, cloaks, robes, coverlets, golden vases (ex hereditate Attalica aulaea, clamides, pallae, plagae, vasa aurea).

- Musei Capitolini, Rome, inv. nos NCE 2385, 2386. CIL6.1375.See Chioffi (2004, 89–91).

- Lewis and Short (1879) s.v. barbaricarius.

- Sinnigen (1963, 807).

- For example, CIL 5.785 and CIL 13.1. See also Rey-Coquais (1995, 78–79).

- Gleba (2008, 63).

- Sebesta (2001, 72).

- Demosthenes, 21.22.

- Claudian, Panegyric to Probinus 181.

- Gleba (2008, 69).

- Rey-Coquais (1995, 79); Gleba (2008, 63).

Bibliography

- Abbe, M. (2010) Recent Research on the Painting and Gilding of Roman Marble Statuary at Aphrodisias. In V. Brinkmann, O.Primavesi and M. Hollein (eds), Circumlitio. The Polychromy of Antique and Medieval Sculpture, 277–289. Munich, Hirmer.

- Barber, E. (1991) Prehistoric Textiles: The Development of Cloth in the Neolithic and Bronze Ages with Special Reference to the Aegean. Chichester, Princeton University Press.

- Bedini, A., Rapinesi, I.A. and Ferro, D. (2004) Testimonianze di filati e ornamenti in oro nell’abbigliamento di etá romana. In C. Alfaro Giner, J.-P. Wild and B. Costa (eds), Purpuae vestes: Actas del I Symposium International sobre Textiles y Tines del Mediterraneo en época romana, 77–95. Valencia, Universitat de València.

- Blume, C. (2010) When Colour Tells a Story – The Polychromy of Hellenistic Sculpture and Teracottas. In V. Brinkmann, O.Primavesi and M. Hollein (eds), Circumlitio. The Polychromy of Antique and Medieval Sculpture, 240–257. Munich, Hirmer.

- Blume, C. (2015) Polychromie Hellenistischer Skulptur. Petersberg, Imhof.

- Bonfante, L. (2003) Etruscan Dress. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Bostock, J. (1855) The Natural History. Pliny the Elder. London, Taylor and Francis.

- Bourgeois, B. (2010) Arts and Crafts of Colour on the Louvre Tanagra Figurines. In V. Jeammet (ed.), Tanagras. Figurines for Life and Eternity, 238–243. Valencia, Fundación Bancaja.

- Bourgeois, B. and Jockey, P. (2010) The Polychromy of Hellenistic Marble Sculpture in Delos. In V. Brinkmann, O. Primavesi and M. Hollein (eds), Circumlitio. The Polychromy of Antique and Medieval Sculpture, 225–239. Munich, Hirmer.

- Brecoulaki, H. (2014) Precious Colours in Ancient Greek Polychromy and Painting: Material Aspects and Symbolic Values. Revue archéologique 57, 3–35.

- Brinkmann, V., Dreyfuss, R. and Koch-Brinkmann, U. (eds) (2017) Gods in Color. Polychromy in the Ancient World. Munich, Prestel.

- Brookes More (1922) Ovid. Metamorphoses. Boston, Cornhill Publishing Co.

- Brøns, C. (2014) Representation and Realities: Fibulas and Pins in Greek and Near Eastern Iconography. In M. Harlow and M.-L. Nosch (eds), Greek and Roman Textiles and Dress: An Interdisciplinary Anthology, 60–94. Oxford, Oxbow Books.

- Brøns, C. (2016) Gods and Garments. Textiles in Greek Sanctuaries in the 7th to the 1st Centuries BC. Oxford, Oxbow Books.

- Brøns, C., Hedegaard, S.B. and Rasmussen, K.L. (2018) The Real Thing? Studies of Polychromy and Authenticity of Etruscan Pinakes at the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek. Studi Etruschi 79. 2014, 195–223.

- Bundgaard-Rasmussen, B. (1998) Gold Ornaments from the Mausoleum of Halikarnassos. In D. Williams (ed.), The Art of the Greek Goldsmith, 66–73. London, British Museum.

- Chioffi, L. (2004) Attalica e altre auratae vestes a Roma. In C. Alfaro, J.-P. Wild and B. Costa (eds), Purpurae Vestes. Actas del I Symposium Internacional sobre Textiles y Tintes del Mediterráneo en época romana 2002, 89–96. Valencia, Universitat de València.

- Chrysostomou, P. and Chrysostomou, A. (2012) The Lady of Archontiko. In P. Stampolidis and G. Giannopoulou (eds), Princesses of the Mediterranean in the Dawn of History. Athens, Museum of Cycladic Art.

- Cleland, L., Davies, G. and Llewellyn-Jones, L. (2007) Greek and Roman Dress A to Z. London, Routledge.

- D’Orazio, L. and Martuscelli, E. (1999) Il tessile a Pompeii: tecnologia, industria e commercio. In A. Ciarallo and E. De Carolis (eds), Homo Faber. Natura, scienza e tecnica nell’antica Pompeii, 92–94. Milano, Electa.

- Droß-Krüpe, K. and Paetz gen. Schieck, A. (2014) Unravelling the Tangled Threads of Ancient Embroidery – a Compilation of Written Sources and Archaeologically Preserved Textiles. In M. Harlow and M.-L. Nosch (eds), Greek and Roman Textiles and Dress: An Interdisciplinary Anthology, Ancient Textiles Series 19, 207–236. Oxford, Oxbow Books.

- Eastaugh, N., Walsh, V., Chaplin, T. and Siddall, R. (2004) Pigment Compendium. A Dictionary of Historical Pigments. London–New York, Routledge.

- Garcia, A. and Conroy, D.W. (2010) A Golden Garment? Identifying New Ways of Looking at the Past through a Preliminary Report of Textile Fragments from the Pafos ‘Erotes’ Sarcophagus. In H. Yeatman (ed.), The SInet 2010 eBook, Research Online 2010-10-27T07:00:00Z https://ro.uow.edu.au/scipapers/1023/, 36–46 (accessed July 2021).

- Gleba, M. (2008) Auratae Vestes: Gold Textiles in the Ancient Mediterranean. In C. Alfaro and L. Karali (eds), Purpurae Vestes. Il Symposium Internacional sobre Textiles y Tintes del Mediterráreo en el mundo antiguo, 61–77. Valencia, Universitat de València.

- Harlow, M. (2005) Dress in the Historia Augusta: The Role of Dress in Historical Narrative. In L. Cleland, M. Harlow and L. Llewellyn-Jones (eds), The Clothed Body in the Ancient World, 143–153. Oxford, Oxbow Books.

- Jeammet, V. (2010) Tanagras. Figurines for Life and Eternity. The Musée du Louvre’s Collection of Greek Figurines. Valencia, Fundación Bancaja.

- Jeppesen, K. (2000) The Maussolleion at Halikarnassos. Vol. 4. The Quadrangle. The Foundations of the Maussolleion and its Sepulchral Compartments. Aarhus, Aarhus University Press.

- Lewis, C.T. and Short, C. (1879) A Latin Dictionary. Oxford, Clarendon Press.

- Linders, T. (1972) Studies in the Treasure Records of Artemis Brauronia Found in Athens. Stockholm, P. Åstrøm.

- Mactaggart, P. and Mactaggart, A. (2011) Practical Gilding. London, Archetype Publications.

- Magie, D. (1921) Historia Augusta. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press.

- Makaronas, C. (1963) Τάφοι παρα το Δερβένι Θεσσαλονίκης. ArchDelt 18, 193–196.

- Nielsen, A.M. and Østergaard, J.S. (1997) Catalogue: The Eastern Mediterranean in the Hellenistic Period. Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek. Copenhagen, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek.

- Nosch, M.-L. (2016) Spinning Gold and Casting Textiles. In J. Driessen (ed.), RA-PI-NE-U. Studies on the Mycenaean World Offered to Robert Laffineur for his 70th Birthday, 221–232. Louvain-La-Neuve, UCL Presses Universitaires de Louvain.

- Oddy, A. (1981) Gilding Through the Ages. An Outline History of the Process in the Old World. Gold Bulletin 14.2, 75–79.

- Pagés-Camagna, S. (2010) Terracottas and Colour. In V. Jeammet (ed.), Tanagras. Figurines for Life and Eternity, 250–251. Valencia, Fundación Bancaja.

- Rey-Coquais, J.-P. (1995) Textiles, soie principalement, et artisanat du textile dans les inscriptions grecques du proche Orient. Studies in the History and Archaeology of Jordan V, 77–81. Amman, Department of Antiquities.

- Ridgway, B.S. (1981) Fifth Century Styles in Greek Sculpture. Princeton, Princeton University Press.

- Sebesta, J.L. (2001) Tunica Ralla, Tunica Spissa: The Colors and Textiles of Roman Costume. In J.L. Sebesta and L. Bonfante (eds), The World of Roman Costume, 65–76. Madison, University of Wisconsin Press.

- Shams, G.P. (1987) Some Minor Textiles in Antiquity. Göteborg, Åström.

- Sinnigen, W.G. (1963) Barbaricarii, Barbari and the Notitia Dignitatum. Latomus 22, fasc. 4, 806–815.

- Stewart, S. (2007) Cosmetics and Perfumes in the Roman World. Gloucestershire, The History Press.

- Touratsoglou, I. (2011) Φιλωτέρα Αμυμώνης. Από την κοσμηματοθήκη του Εθνικού Αρχαιολογικού Μουσείου. Το Μουσείον 2, 93–102.

- Tzanavari, K. (2012) An Example of a Gold-Woven Silk Textile in the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki. In I. Tzachili and E.Zimi (eds), Textiles and Dress in Greece and the Roman East: A Technological and Social Approach, 25–34. Athens, Ta Pragmata.

- Williams, D. and Ogden, J. (1994) Greek Gold. Jewellery of the Classical World. London, British Museum Press.

- Zink, S. (2019) Polychromy, Architectural, Greek and Roman. Oxford Classical Dictionary. [online] DOI:10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.818.

Chapter 9 (121-137) from Textiles in Ancient Mediterranean Iconography (Ancient Textiles Series 38), edited by Susanna Harris, Cecilie Brøns AND Marta Zuchowska, (Oxbow Books, 02.03.2022), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.