Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

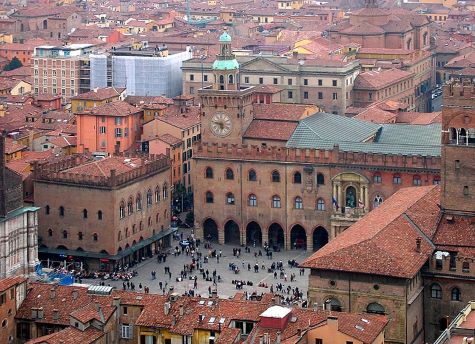

The University of Bologna is a research university in Bologna, Italy. Founded in 1088 by an organised guild of students (hence studiorum), it is the oldest university in continuous operation in the world, and the first university in the sense of a higher-learning and degree-awarding institute, as the word universitas was coined at its foundation.[3][4][5][6]

It is one of the most prestigious Italian universities, commonly ranking in the first places of national, European and international rankings both as a whole and for individual subjects.[7][8] Since its foundation, it has attracted numerous scholars, intellectuals and students from all over Italy and the world, establishing itself as one of the main international centers of learning.[9]

It was the first place of study to use the term universitas for the corporations of students and masters, which came to define the institution (especially its famous law school) located in Bologna. The university’s emblem carries the motto Alma mater studiorum (“Nourishing mother of studies”) and the date A.D. 1088, and it has about 86,500 students in its 11 schools.[10] It has campuses in Cesena, Forlì, Ravenna and Rimini and a branch center abroad in Buenos Aires, Argentina.[11] It also has a school of excellence named Collegio Superiore di Bologna. An associate publisher of the University of Bologna is the Bononia University Press.

The University of Bologna saw the first woman to earn a university degree and teach at a university, Bettisia Gozzadini, and the first woman to earn both a doctorate in science and a salaried position as a university professor, Laura Bassi.

History

The date of the University of Bologna’s founding is uncertain, but believed by most accounts to have been 1088.[12] The university was granted a charter (Authentica habita) by Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa in 1158, but in the 19th century, a committee of historians led by Giosuè Carducci traced the founding of the University back to 1088, which would make it the oldest continuously-operating university in the world.[13][14][15] However, the development of the institution at Bologna into a university was a gradual process. Paul Grendler writes that “it is not likely that enough instruction and organization existed to merit the term university before the 1150s, and it might not have happened before the 1180s.”[16]

The university arose around mutual aid societies (known as universitates scholarium) of foreign students called “nations” (as they were grouped by nationality) for protection against city laws which imposed collective punishment on foreigners for the crimes and debts of their countrymen. These students then hired scholars from the city’s pre-existing lay and ecclesiastical schools to teach them subjects such as liberal arts, notarial law, theology, and ars dictaminis (scrivenery).[17] The lectures were given in informal schools called scholae. In time the various universitates scholarium decided to form a larger association, or Studium—thus, the university. The Studium grew to have a strong position of collective bargaining with the city, since by then it derived significant revenue through visiting foreign students, who would depart if they were not well treated. The foreign students in Bologna received greater rights, and collective punishment was ended. There was also collective bargaining with the scholars who served as professors at the university. By the initiation or threat of a student strike, the students could enforce their demands as to the content of courses and the pay professors would receive.

University professors were hired, fired, and had their pay determined by an elected council of two representatives from every student “nation” which governed the institution, with the most important decisions requiring a majority vote from all the students to ratify. The professors could also be fined if they failed to finish classes on time, or complete course material by the end of the semester. A student committee, the “Denouncers of Professors”, kept tabs on them and reported any misbehavior. Professors themselves were not powerless, however, forming collegia doctorum (professors’ committees) in each faculty, and securing the rights to set examination fees and degree requirements. Eventually, the city ended this arrangement, paying professors from tax revenues and making it a chartered public university.[18]

The university is historically notable for its teaching of canon and civil law;[19] indeed, it was set up in large part with the aim of studying the Digest,[20] a central text in Roman law, which had been rediscovered in Italy in 1070, and the university was central in the development of medieval Roman law.[21] Until modern times, the only degree granted at that university was the doctorate.

Bettisia Gozzadini earned a law degree in 1237, being one of the first women in history to obtain a university degree.[22] She taught law from her own home for two years, and in 1239 she taught at the university, becoming the first woman in history to teach at a university.[23]

In 1477, when Pope Sixtus IV issued a papal bull, authorizing the creation of Uppsala University in Sweden, the bull specified that the new university would have the same freedoms and privileges as the University of Bologna – a highly desirable situation for the Swedish scholars. This included the right of Uppsala to establish the four traditional faculties of theology, law (Canon Law and Roman law), medicine, and philosophy, and to award the bachelor’s, master’s, licentiate, and doctoral degrees.

Laura Bassi was born into a prosperous family of Bologna and was privately educated from the age of five.[24] Bassi’s education and intellect was noticed by Prospero Lorenzini Lambertini, who became the Archbishop of Bologna in 1731 (later Pope Benedict XIV). Lambertini became the official patron of Bassi. He arranged for a public debate between Bassi and four professors from the University of Bologna on 17 April 1732.[25] In 1732, Bassi, aged twenty, publicly defended her forty-nine theses on Philosophica Studia[26] at the Sala degli Anziani of the Palazzo Pubblico. The University of Bologna awarded her a doctorate degree on 12 May.[27] She became the first woman to receive a doctorate in science, and the second woman in the world to earn a philosophy doctorate after Elena Cornaro Piscopia in 1678, fifty-four years prior. She was by then popularly known as Bolognese Minerva.[28][24] On 29 October 1732, the Senate and the University of Bologna granted Bassi’s candidature, and in December she was appointed professor of natural philosophy to teach physics.[29][30] She became the first salaried woman lecturer in the world,[31] thus beginning her academic career. She was also the first woman member of any scientific establishment, when she was elected to the Academy of Sciences of the Institute of Bologna in 1732.[32][33] Bassi became the most important populariser of Newtonian mechanics in Italy.[34]

Organization

Higher education processes are being harmonised across the European Community. Nowadays the university offers 101 different “Laurea” or “Laurea breve” first-level degrees (three years of courses), followed by 108 “Laurea specialistica” or “Laurea magistrale” second-level degrees (two years). However, other 11 courses have maintained preceding rules of “Laurea specialistica a ciclo unico” or “Laurea magistrale a ciclo unico“, with only one cycle of study of five years, except for medicine and dentistry which requires six years of courses. After the “Laurea” one may attain 1st level Master (one-year diploma, similar to a Postgraduate diploma). After second-level degrees are attained, one may proceed to 2nd level Master, specialisation schools (residency), or doctorates of research (PhD).

The 11 Schools (which replace the preexisting 23 faculties) are:

- School of Agriculture and Veterinary Medicine

- School of Economics, Management and Statistics

- School of Engineering and Architecture

- School of Foreign Languages and Literature, Interpretation and Translation

- School of Law

- School of Arts, Humanities, and Cultural Heritage

- School of Medicine and Surgery

- School of Pharmacy, Biotechnologies and Sport Sciences

- School of Political Sciences

- School of Psychology and Education Sciences

- School of Sciences

The university is structured in 33 departments[35] (there were 66 until 2012), organized by homogeneous research domains that integrate activities related to one or more faculty. A new department of Latin history was added in 2015.

The 33 departments are:

- Architecture – DA

- Cultural Heritage – DBC

- Chemistry “Giacomo Ciamician” – CHIM

- Industrial Chemistry “Toso Montanari” – CHIMIND

- Arts – DARvipem

- Pharmacy and Biotechnology – FaBiT

- Classical Philology and Italian Studies – FICLIT

- Philosophy and Communication Studies – FILCOM

- Physics and Astronomy – DIFA

- Computer Science and Engineering – DISI

- Civil, Chemical, Environmental, and Materials Engineering – DICAM

- Electrical, Electronic, and Information Engineering “Guglielmo Marconi” – DEI

- Industrial Engineering – DIN

- Interpreting and Translation – DIT

- Modern Languages, Literatures, and Cultures – LILEC

- Mathematics – MAT

- Experimental Medicine, Diagnostic Medicine and Specialty Medicine – DIMES

- Psychology – PSI

- Agricultural Sciences – DipSA

- Management – DiSA

- Biological, Geological, and Environmental Sciences – BiGeA

- Biomedical and Neuromotor Sciences – DIBINEM

- Education Studies “Giovanni Maria Bertin” – EDU

- Agricultural and Food Sciences – DISTAL

- Economics – DSE

- Legal Studies – DSG

- Medical and Surgical Sciences – DIMEC

- Veterinary Medical Sciences – DIMEVET

- Department for Life Quality Studies – QUVI

- Political and Social Sciences – SPS

- Statistical Sciences “Paolo Fortunati” – STAT

- Sociology and Business Law – SDE

- History and Cultures – DiSCi

Affiliates and Other Institutions

Il Mulino

In the early 1950s, some students of the University of Bologna were among the founders of the review “il Mulino”. On 25 April 1951 the first issue of the review was published in Bologna.[36] In a short time, “il Mulino” became one of the most interesting reference points in Italy for the political and cultural debate, and established important editorial relationships in Italy and abroad. Editorial activities evolved along with the review. In 1954, the il Mulino publishing house (Società editrice il Mulino) was founded, which today represents one of the most relevant Italian publishers. In addition to this were initiated research projects (focusing mostly on the educational institutions and the political system in Italy), that eventually led, in 1964, to the establishment of the Istituto Carlo Cattaneo.

Collegio Superiore

The Collegio Superiore is an excellence institution inside the University of Bologna, aimed at promoting students’ merit through dedicated learning programmes.

The institution was founded in 1998 as Collegio d’Eccellenza. Together with the Institute for Advanced Study it is part of the Institute for Higher Study.

The Collegio Superiore offers an additional educational path to students enrolled in a degree programme at the University of Bologna, providing specialized courses as part of an interdisciplinary framework.

All students of the Collegio Superiore are granted a full-ride scholarship and additional benefits such as the assistance of a personal tutor and free accommodation at the Residence for Higher Study. In order to remain members of the Collegio Superiore students are required to maintain high marks in both their degree programme and the additional courses.

Beatrice Fraboni, professor of Physics of Matter, has been head of Collegio Superiore since 2019.[37]

Endnotes

- Charters of foundation and early documents of the universities of the Coimbra Group, Hermans, Jos. M. M.

- “The University today: numbers and innovation”

- Top Universities Archived 17 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine World University Rankings Retrieved 6 January 2010

- Paul L. Gaston (2010). The Challenge of Bologna. p. 18.

- Hunt Janin: “The university in medieval life, 1179–1499”, McFarland, 2008, p. 55f.

- de Ridder-Symoens, Hilde: A History of the University in Europe: Volume 1, Universities in the Middle Ages, Cambridge University Press, 1992, pp. 47–55

- Dieci volte prima: l’Università di Bologna ancora al top in Italia tra i mega atenei.

- “Europe – Ranking Web of Universities”. www.webometrics.info.

- “Most international universities in the world”. Times Higher Education (THE). 2020-01-28. Retrieved 2020-12-17.

- “Schools”. University of Bologna. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- “Campuses and Structures”. University of Bologna. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- Università di Bologna

- Top Universities Archived 2008-01-15 at the Wayback Machine World University Rankings Retrieved 2010-1-6

- Our History – Università di Bologna

- Paul L. Gaston (2012). The Challenge of Bologna: What United States Higher Education Has to Learn from Europe, and Why It Matters That We Learn It. Stylus Publishing, LLC. p. 18.

- Paul F. Grendler, The Universities of the Italian Renaissance (JHU Press, 2002), 6.

- David A. Lines, “The University and the City: Cultural Interactions”, in A Companion to Medieval and Renaissance Bologna, ed. Sarah Rubin Blanshei (Leiden: Brill, 2017), 437–8.

- A University Built by the Invisible Hand, by Roderick T. Long. This article was published in the Spring 1994 issue of Formulations, by the Free Nation Foundation.

- “University of Bologna | History & Development”. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2017-08-21.

- Berman, Law and Revolution, ch. 3; Stein, Roman Law in European History, part 3.

- See Corpus Juris Civilis: Recovery in the West

- Murphy, Caroline P. (1999). “‘In praise of the ladies of Bologna’: the image and identity of the sixteenth-century Bolognese female patriciate”. Renaissance Studies. 13 (4): 440–454. doi:10.1111/j.1477-4658.1999.tb00090.x. ISSN 0269-1213. JSTOR 24412719. PMID 22106487.

- Bonafede, Carolina (1845). Cenni biografici e ritratti d’insigni donne bolognesi: raccolti dagli storici più accreditati (in Italian). Sassi.

- Laura Bassi at Encyclopedia.com

- “Laura Bassi (1711 – 1778)”. mathshistory.st-andrews.ac.uk. Retrieved 2020-05-20.

- “Women In The History Of Philosophy”. www.encyclopedia.com. 2020. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- Elena, Alberto (1991). “”In lode della filosofessa di Bologna”: An Introduction to Laura Bassi”. Isis. 82 (3): 510–518. doi:10.1086/355839. S2CID 144763731.

- Frize, Monique (2013), “Famous Women in Science in Laura Bassi’s Epoch”, Laura Bassi and Science in 18th Century Europe, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 137–162

- Monique Frize, Laura Bassi and Science in 18th Century Europe: The Extraordinary Life and Role of Italy’s Pioneering Female Professor, Springer, p. 174.

- Findlen, Paula (2013-08-29). “Laura Bassi and the city of learning”. Physics World. Retrieved 2020-05-20.

- Frize, Monique (2013). “Epilogue”. Laura Bassi and Science in 18th Century Europe. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 173–181.

- “Laura Bassi | Italian scientist”. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-08-30.

- “Laura BASSI”. scientificwomen.net. Retrieved 2020-08-30.

- Findlen, Paula (1993). “Science as a career in Enlightenment Italy: The strategies of Laura Bassi”. Isis. 84 (3): 441–469. doi:10.1086/356547. JSTOR 235642. S2CID 144024298.

- List of the Departments of the University of Bologna

- “La Società editrice”. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- “Beatrice Fraboni è la nuova direttrice del Collegio Superiore”. 2019-07-08. Retrieved 2020-02-06.

Originally published by Wikipedia, 07.08.2003, under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.