History was not only written but argued, performed, and contested.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

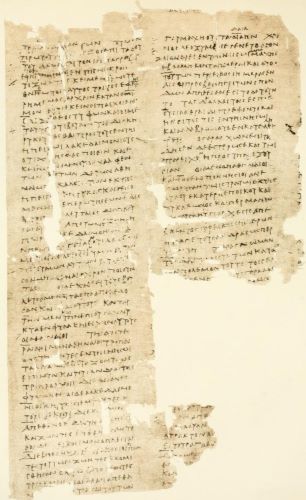

From the earliest inscriptions carved into stone to the scrolls meticulously penned by court-appointed chroniclers, the ancient historiographer played a role both revered and precarious. Tasked with preserving the past, these figures were not mere recorders of events but interpreters of meaning, often blending memory, ideology, and narrative to forge a usable history. The ancient world—rich in political tumult, cultural revolutions, and philosophical reflection—produced historiographers whose works endure not only for their documentary value but for their profound impact on the historiographical tradition itself. Here I explore the historiographical traditions of key ancient civilizations—particularly Greece and Rome, but with reference to Egypt, Mesopotamia, and China—and examine how these early chroniclers understood their task, whom they served, and the legacies they left behind.

The Nature of Ancient Historiography

The practice of historiography in the ancient world diverged sharply from modern historical methodologies in both purpose and form. Ancient historiographers were not passive chroniclers but active shapers of collective memory, constructing narratives that served moral, political, and often theological ends. Rather than aspiring to detached objectivity, they embraced the inherently rhetorical nature of their craft. Herodotus, for example, set out in his Histories not simply to recount past events but to ensure that “the great and marvelous deeds” of Greeks and non-Greeks alike would be remembered, thereby blending ethnography, folklore, and moral reflection into a unified historical tapestry.1 Ancient historiography was thus less a forensic exercise than an art of public discourse—one that reflected as much about the historian’s present as it did about the past being described.

Truth, in this context, was not synonymous with empirical accuracy. It was often equated with moral coherence or divine order. Events were selected, framed, and interpreted according to their perceived significance in a broader cosmic or civic framework. This is perhaps most evident in Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War, where the emphasis on causation, political analysis, and human nature reflects a deliberate attempt to uncover patterns of behavior rather than to catalog every incident. Thucydides famously claimed that his work was intended as “a possession for all time,” signifying a belief that the value of history lay in its ability to instruct future generations through paradigmatic examples.2 Ancient historiography, therefore, operated on the assumption that the past was a reservoir of lessons—moral, strategic, and philosophical—rather than a neutral sequence of occurrences.

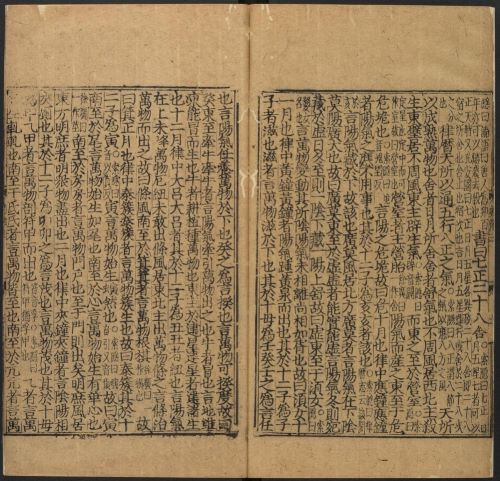

This ethical orientation also meant that the historiographer’s role was often deeply entangled with ideology and power. In Rome, the function of history was inseparable from the task of glorifying the mos maiorum and legitimizing imperial rule. Livy, in his monumental Ab Urbe Condita, sought to recover the spirit of Rome’s early virtue, using historical narrative to contrast the moral fiber of the past with the decadence of his present age.3 Similarly, in the East, Sima Qian’s Shiji exemplified a historiographical approach rooted in Confucian ethics and dynastic legitimacy. Though Sima Qian introduced an analytical rigor and personal voice rarely seen in earlier Chinese annals, his understanding of history was still shaped by the notion of the Mandate of Heaven—the belief that moral virtue determined the rise and fall of dynasties.4 Thus, ancient historiography across cultures was imbued with a teleological structure, often tracing an arc from moral ascent to decline, and occasionally to redemption.

Ancient historiographers were often compelled to navigate competing loyalties: to truth, to audience, and to authority. Many, like Tacitus, masked their critiques of imperial corruption in irony and allusion, crafting narratives that simultaneously recorded and resisted power. Others, like Josephus, wrote under duress or for foreign patrons, leading to charges of partiality and revisionism. The tension between fidelity to fact and service to power was ever-present, and it is this very tension that gives ancient historiography much of its literary and philosophical weight. Far from diminishing their work, the rhetorical and ideological underpinnings of ancient historiography illuminate the historian’s own struggle with memory, allegiance, and interpretation.

The nature of ancient historiography lies not only in what was written but in how and why it was written. It was a conscious act of shaping meaning from the chaos of human affairs, guided by cultural values, philosophical systems, and political exigencies. Modern historians may critique the biases and limitations of ancient works, but these texts remain indispensable precisely because they reveal the intellectual scaffolding upon which civilizations constructed their pasts. They teach us that history is never a passive mirror but always a crafted lens—one that reflects, refracts, and sometimes distorts, but never forgets its duty to speak to the living through the voice of the dead.

Greek Historiography: Between Inquiry and Identity

The historiographical tradition of ancient Greece marked a foundational shift in how human societies conceptualized the past, moving beyond annalistic records or mythopoetic recollections to a sustained inquiry into causation, character, and civic identity. At its core, Greek historiography emerged not only as a means of documenting events but as a vehicle for self-understanding—both individual and communal. The earliest Greek historians framed their work through the lens of historia, or inquiry, suggesting a methodological curiosity about the patterns and principles underlying historical phenomena. Herodotus of Halicarnassus, writing in the fifth century BCE, inaugurated this tradition by seeking to explain the causes of the Greco-Persian Wars. Yet his Histories served not merely as a chronicle of conflict, but as an ethnographic and moral meditation on the behaviors and beliefs of both Greeks and “barbarians.” Through his juxtaposition of cultural practices, Herodotus not only attempted to understand foreign customs but to illuminate the values that defined the Hellenic world in contrast to its others.5

Herodotus’s project was not without tensions. While he professed an intent to preserve the memory of great deeds from both sides of the conflict, his narrative choices betray a deep concern with identity formation. His depiction of Persian hubris and Greek valor, though nuanced at times, often reinforces a binary opposition that reflects the ideological imperatives of postwar Greece. Moreover, Herodotus frequently embeds divine causality and oracular pronouncements into his historiography, signaling an enduring connection between mythic modes of explanation and emerging empirical ones. The result is a hybrid form: part travel narrative, part ethnography, part theological reflection, and part political commentary. This complexity reflects the unstable but fertile ground upon which Greek historiography was born—between oral tradition and literate rationalism, between communal memory and analytical detachment.6 As such, Herodotus’s Histories represent not the culmination of a historiographical form but its experimental genesis, charting the contours of what Greek historical consciousness might become.

It is with Thucydides, writing only a generation later, that Greek historiography took a decisive turn toward analytical rigor and political realism. In his History of the Peloponnesian War, Thucydides rejected the mythic, anecdotal, and theological framework of his predecessor, offering instead a tragic vision of human behavior governed by necessity, power, and fear. His methodology—critical sourcing, eyewitness testimony, and the reconstruction of plausible speeches—sought to elevate historiography to the level of systematic political analysis. For Thucydides, the war between Athens and Sparta was not merely a clash of states but a revelatory moment in the nature of human political life. His work, often bleak and unsparing, exposed the moral ambiguities and strategic miscalculations that drive history forward. Yet even as he eschewed divine causation, Thucydides retained a tragic sensibility—one that viewed the recurrence of certain patterns as almost fated, if not metaphysically ordained.7

Both Herodotus and Thucydides demonstrate that Greek historiography was never merely about recording events; it was an ongoing inquiry into the meaning of polis, ethnos, and the conditions of communal life. The tensions between freedom and tyranny, reason and fate, virtue and expediency—so central to classical Greek thought—are also the philosophical substrata of their historical writings. Indeed, in their differing styles and emphases, Herodotus and Thucydides encapsulate the dual inheritance of Greek historiography: one that seeks to understand the world through interpretive storytelling, and another that aims to dissect it through rational analysis. Subsequent historians like Xenophon and Polybius would elaborate on these traditions in their own ways, but the dialectic between inquiry and identity remained foundational. Polybius, for instance, while writing under Roman dominance, sought to explain the rise of Rome in terms that drew on Greek political theory, thereby grafting Hellenic historiographical categories onto a new imperial reality.8

What ultimately distinguishes ancient Greek historiography from other ancient narrative traditions is its reflexivity. Greek historians were acutely aware of the constructed nature of historical narrative and the stakes involved in shaping it. The incorporation of speeches—whether real or invented—reflected not only a concern with rhetorical verisimilitude but an acknowledgment that history was a contest of interpretations, not merely facts. This historiographical self-consciousness helped solidify history’s place within the Greek intellectual tradition, alongside philosophy, drama, and rhetoric. It also meant that writing history was an act of civic engagement, a way of participating in the polis even from a position of exile or marginality. Whether through Herodotus’s comparative ethnography or Thucydides’ forensic realism, Greek historiographers interrogated the nature of human agency, the fragility of political order, and the paradoxes of power—questions that remain as urgent today as they were in the ancient world.9

Roman Historiography: Exemplarity and Empire

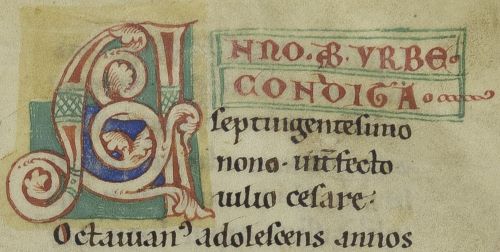

Roman historiography, though indebted to the Greek tradition, developed a distinctive character grounded in Roman moral, political, and legal culture. While Greek historiography centered on inquiry (historia) and the philosophical interpretation of events, Roman historians were deeply concerned with exempla—moral examples meant to instruct future citizens and reaffirm the foundational virtues of the Republic. History, for the Romans, was not merely a record of past events but a mirror of public ethics and civic responsibility. This exemplarity served a didactic purpose, reinforcing ideals such as virtus, fides, gravitas, and pietas—traits believed essential to the preservation of Rome’s greatness. Early annalists like Quintus Fabius Pictor laid the groundwork, but it was Livy who would most fully embody this impulse in his monumental Ab Urbe Condita, which sought to trace Rome’s rise from its mythic origins to the present moment with a moralizing tone rooted in nostalgia for a lost republican virtue.10

Livy’s historical narrative is suffused with reverence for Rome’s foundational heroes, from Romulus and Horatius Cocles to Camillus and Scipio Africanus. In Livy’s hands, history becomes an ethical drama, in which virtuous conduct is extolled and moral decay is subtly condemned. Writing during the Augustan regime, Livy was keenly aware of the tension between Republican ideals and the reality of imperial consolidation. His history does not overtly criticize Augustus, but by elevating figures of the Republican past, he implicitly contrasts their moral rigor with the perceived decadence of contemporary Rome. Livy’s historiography thus serves a dual function: on the one hand, it legitimizes Roman supremacy by narrating its divine and virtuous origins; on the other, it mourns the erosion of civic virtue under autocracy. His invocation of exempla was not merely literary but political—an appeal to Rome’s collective conscience to remember who they once were.11

Sallust, a near contemporary of Livy, took a more explicitly critical tone. His monographs on the Catilinarian Conspiracy and the Jugurthine War are tightly constructed political commentaries on Rome’s moral and institutional collapse. Unlike Livy’s sweeping epic, Sallust’s histories are polemical, bitter, and concise. A former politician disillusioned with the corruption of the late Republic, Sallust saw in history a means of diagnosing civic illness. His works emphasize the rise of avaritia (greed) and ambitio (self-serving ambition) as the vices that destroyed Rome’s traditional order. In his Bellum Catilinae, Sallust describes how internal rot, not external threat, brought the Republic to its knees. His prose is pointed, his analysis stark, and his historiographical vision one of decline—a fall from the virtuous simplicity of earlier generations into decadence and civil strife.12

Tacitus, writing under the early empire, deepened this tragic sensibility. His Annals and Histories portray the Julio-Claudian and Flavian dynasties with caustic irony and psychological acuity. For Tacitus, history is a moral battleground in which truth must be excavated from beneath layers of imperial propaganda. His depiction of emperors like Tiberius, Nero, and Domitian is not only political but philosophical—a meditation on the corrupting effects of absolute power. Tacitus’s style is compressed and elliptical, filled with rhetorical density and dark understatement. Like Sallust, he believed that the loss of liberty under empire entailed not just political subjugation but the degradation of language, memory, and moral agency. Yet unlike Sallust, Tacitus wrote from within the imperial structure, aware of its dangers but also of its permanence. His historical method combines forensic investigation, moral reflection, and literary artistry, offering a vision of Rome’s imperial age that is both profoundly insightful and deeply disillusioned.13

While Greek historians like Thucydides dissected political behavior to uncover general laws of human conduct, Roman historiographers framed history as a vehicle of memory and civic identity—especially in the context of an evolving empire. Even historians like Polybius, a Greek writing in Latinized Rome, adapted their analysis to Roman paradigms. His account of Rome’s constitutional mixed government and military prowess was intended not just to describe but to explain Rome’s ascendancy. Roman historiography thus became a theater of empire: a place where the past was constructed to justify present realities. Whether through Livy’s moral exemplars, Sallust’s political critique, or Tacitus’s somber reflections on power, Roman historians shaped not just how Romans viewed their history, but how they understood themselves as a people. Their works endure not only because of their literary brilliance but because they reveal the profound interdependence of memory, morality, and empire in Roman thought.14

Eastern Historiography: Annals, Cosmology, and Mandate

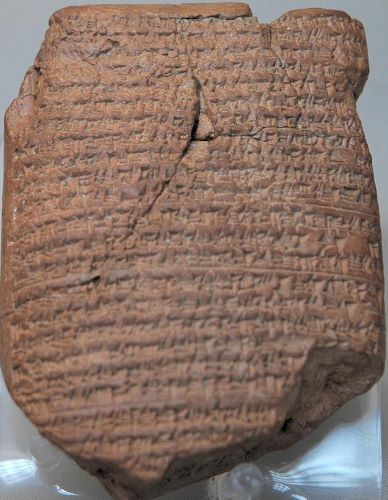

The historiographical traditions of the ancient East—encompassing Mesopotamia, Egypt, Persia, and China—differed in fundamental ways from the Greco-Roman model. While Western historiography emphasized rational inquiry, ethical exemplarity, and political realism, Eastern traditions often framed history within a cosmological and theological structure. In Mesopotamia and Egypt, historical writing was largely inscribed in the service of royal legitimation and divine order. Kings like Sargon of Akkad or Ramses II recorded their military exploits and building campaigns not as mere chronicles, but as manifestations of divine will and cosmic harmony. These early inscriptions, such as the Sumerian King List or Egyptian royal annals, rarely questioned the legitimacy of rule; instead, they reinforced a theocratic worldview in which temporal events mirrored celestial decrees. History in these contexts was not a forum for debate or moral introspection, but a medium for affirming dynastic continuity and sacred authority.15

This intertwining of history and cosmology is especially evident in ancient Egyptian historiography. Pharaohs were not simply rulers but incarnations of divine order (ma’at), tasked with maintaining balance between chaos and harmony. Their deeds—inscribed on temple walls and monumental stelae—were thus framed as sacred acts. The Annals of Thutmose III at Karnak, for example, present the king’s military victories not as empirical campaigns but as ordained triumphs over chaos, authorized by the god Amun. These records lack analytical narrative and offer little in the way of causation or critique. Instead, they function as ritual affirmations of divine favor and royal legitimacy. The past was cyclically structured and morally fixed, with the pharaoh’s role serving to restore order disrupted by rebellion, natural disaster, or foreign incursion.16 Unlike Thucydidean or Tacitean skepticism, ancient Egyptian historiography did not accommodate the notion of political failure—only temporary disorder awaiting cosmic correction.

In Mesopotamia, similar patterns prevailed. The Babylonian Chronicles and the royal inscriptions of Assyrian kings such as Ashurbanipal and Tiglath-Pileser III portrayed history as a sequence of conquests and restorations under divine auspices. These texts often employed formulaic language, boasting of enemy defeats, city destructions, and tribute extractions, all framed as duties fulfilled under the will of gods like Marduk or Ashur. One of the most famous examples is the Behistun Inscription of Darius I of Persia, which blends royal autobiography, political justification, and divine legitimation. Composed in three languages and carved into a mountainside, it narrates Darius’s rise to power through a series of rebellions crushed with the favor of Ahura Mazda. In such texts, the king’s authority is inseparable from cosmic order, and historical memory is shaped not by debate or inquiry, but by theological assertion. These inscriptions, while valuable as historical sources, reflect a historiography that prioritized divine narrative coherence over analytical interpretation.17

China, by contrast, developed a historiographical tradition with greater analytical depth and philosophical reflection, particularly from the late Zhou dynasty onward. The foundational work in Chinese historiography is Sima Qian’s Shiji (Records of the Grand Historian), composed in the second century BCE during the Han dynasty. Sima Qian integrated court records, oral traditions, and personal commentary into a massive narrative that covered over two millennia of Chinese history. While he preserved the annalistic structure of earlier Chinese texts, he infused it with Confucian moral judgment and a proto-sociological interest in patterns of rise and decline. Central to Sima Qian’s framework was the Mandate of Heaven (Tianming), a doctrine that interpreted dynastic succession as contingent upon moral virtue. When rulers failed to uphold virtue, they lost the Mandate, and heaven sanctioned their overthrow. Thus, historical causality was both ethical and metaphysical, combining cosmic order with political legitimacy in a way that gave Chinese historiography its unique moral gravitas.18

What distinguishes ancient Eastern historiography, then, is not the absence of historical consciousness, but its embeddedness within cosmology, ritual, and metaphysics. Rather than constructing history as a field of contested memory and individual agency, Eastern historiographers often conceived it as a record of the moral cosmos in motion. The annals of kings, the chronicles of dynasties, and the cosmic legitimations of power all served to locate human activity within a divine or philosophical framework. Yet even within these constraints, figures like Sima Qian displayed remarkable independence and self-awareness. After defending a disgraced general, Sima Qian was castrated by the emperor, yet he chose to live in shame so he could complete his historical project—a gesture that itself became a moral exemplum. In this tension between duty and critique, between heaven’s order and human suffering, Eastern historiography found its depth. It was not history as dispassionate science, but as ethical cosmology—an inquiry into how the world ought to be, even when it clearly was not.19

Historiographical Ethics and Legacy

The ethics of ancient historiography are inseparable from its rhetorical and philosophical underpinnings. Ancient historians were not passive collectors of facts but engaged moral agents, aware of their responsibility to posterity and often caught between the demands of truth-telling and the exigencies of power. Herodotus, while frequently accused of credulity, defended the inclusion of multiple accounts as a method of honoring memory and recognizing the limits of certainty. His admission that he records what others say—even if he does not always believe it himself—suggests a proto-ethical stance: that the multiplicity of voices is itself a historical good.20 Thucydides, by contrast, pursued a starker realism, asserting that his narrative would be of lasting value precisely because it depicted events not as they ought to be remembered, but as they truly occurred. His commitment to uncovering “the truest cause” of events positions him as the progenitor of a more forensic, even skeptical, historiographical ethos.21 Both approaches, however distinct, affirm that history is a moral act—the selection, arrangement, and interpretation of events involves not just knowledge, but judgment.

Roman historiography deepened the ethical dimensions of historical writing by foregrounding the tension between public virtue and political decline. Livy lamented the loss of traditional Roman values, not as a disinterested observer, but as a moralist using the past to critique the present. His histories were implicitly prescriptive, offering models of civic conduct for a society that had, in his view, strayed from its republican ideals. Similarly, Sallust’s terse narratives cast corruption and greed as the root causes of Rome’s unraveling, using history as an indictment of contemporary decay. Tacitus, perhaps the most ethically fraught of Roman historians, presents an even more anguished view. His Annals expose the psychological cost of tyranny—on both the rulers and the ruled—and dramatize the historian’s burden of writing truth under oppression. Tacitus’s ethic is not the ethic of simple facticity, but of subversive clarity. In an age where speech was policed, he wrote history with layered irony, offering moral insight through ambiguity and allusion.22

In the East, the ethical burden of history was often fused with cosmological obligation. Sima Qian’s Shiji embodies a profound sense of duty—not just to the emperor or the state, but to the dao (the Way) and the moral order it signified. His decision to accept castration rather than execution—so that he might complete his historical work—represents a striking ethical commitment. For Sima Qian, history was not merely a record of past events but a means of preserving moral truth across generations. The doctrine of the Mandate of Heaven gave Chinese historiography a theological framework within which ethical failure had cosmic consequences. Dynasties fell not by accident, but because they failed to uphold virtue. The historian’s role, therefore, was to discern and preserve the moral logic of history, often at great personal cost.23 This confers on Eastern historiography a depth of ethical reflection that is distinct from but parallel to Greco-Roman traditions: not only the chronicling of what happened, but the interpretation of why it ought or ought not to have happened in moral terms.

Across these civilizations, ancient historiographers wrestled with the same fundamental questions that continue to confront historians today: What is the purpose of history? Whom does it serve? What are the moral responsibilities of those who shape collective memory? While their answers varied, what unites them is the belief that history is a public act, not a private indulgence. Whether casting the past in the service of state ideology or resisting that ideology through subversive narration, ancient historians were conscious of their role in shaping the moral and civic fabric of their societies. Their works are not neutral repositories of data but ethical documents—texts that preserve not only events but the values by which those events were judged. This ethical consciousness—however inflected by ideology, theology, or politics—renders ancient historiography not merely a forerunner of modern historical practice, but a perennial touchstone for the responsibilities of historical inquiry.24

The legacy of ancient historiographical ethics lies in their continued influence on later historical writing. Medieval Christian chroniclers inherited the moral paradigms of Roman historiography, framing history as a battle between virtue and vice. Renaissance humanists rediscovered the rhetorical brilliance and civic engagement of Livy and Tacitus, while Enlightenment thinkers admired the critical rationalism of Thucydides and Sima Qian. Even in the modern era, the questions first asked by ancient historians—about truth, power, and memory—continue to animate debates about historical methodology and public responsibility. The ancients did not conceive of history as a science, but as an art of moral discernment. In an age of misinformation and ideological distortion, their insistence that historical writing is inseparable from ethical judgment remains not only relevant but urgently instructive.25

Conclusion

To read the ancient historiographers is to enter a world where history was not only written but argued, performed, and contested. Their narratives were shaped by empire and exile, by triumph and trauma. They wrote with quills of ambition and ink of ideology, and their legacy lies not just in the events they recorded but in the questions they asked—about power, truth, virtue, and memory. Their works endure not simply because they tell us what happened, but because they compel us to ask why—and what it means still.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Herodotus, The Histories, trans. Robin Waterfield (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 3.

- Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, trans. Rex Warner (London: Penguin Classics, 1972), 1.22.

- Livy, The Early History of Rome: Books I–V of The History of Rome from Its Foundation, trans. Aubrey de Sélincourt (London: Penguin Classics, 2002), Preface.

- Sima Qian, Records of the Grand Historian: Han Dynasty I, trans. Burton Watson (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993), 45–47.

- Herodotus, The Histories, 1.1

- Ibid., 2.20–30; 7.139.

- Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, 1.22, 3.82-85.

- Polybius, The Rise of the Roman Empire, trans. Ian Scott-Kilvert (London: Penguin Classics, 1979), 6.1–6.18.

- Xenophon, A History of My Times, trans. Rex Warner (London: Penguin Classics, 1979), Introduction; Thucydides, Peloponnesian War, 2.60–64.

- Livy, The Early History of Rome, Preface.

- Ibid., 1.6–10; 2.1–2.

- Sallust, The Jugurthine War and The Conspiracy of Catiline, trans. S. A. Handford (London: Penguin Classics, 1963), 5–12, 36–37.

- Tacitus, The Annals of Imperial Rome, 1.2, 4.33-35.

- Polybius, The Rise of the Roman Empire, 6.1-18.

- Marc Van De Mieroop, A History of the Ancient Near East ca. 3000–323 BC, 3rd ed. (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2015), 111–113.

- Miriam Lichtheim, Ancient Egyptian Literature, Volume II: The New Kingdom (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1976), 26–32.

- Darius I, The Behistun Inscription, in The Ancient Near East: An Anthology of Texts and Pictures, ed. James B. Pritchard (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011), 200–205.

- Sima Qian, Records of the Grand Historian, 45-47.

- Ibid., 51–54.

- Herodotus, The Histories, 2.123.

- Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, 1.22.

- Tacitus, The Annals of Imperial Rome, 1.1; Sallust, The Jugurthine War and The Conspiracy of Catiline, 3-4.

- Sima Qian, Records of the Grand Historian, 51-54.

- Ibid., 45–47.

- Tacitus, Annals, 3.65; Thucydides, Peloponnesian War, 2.60–64.

Bibliography

- Darius I. The Behistun Inscription. In The Ancient Near East: An Anthology of Texts and Pictures, edited by James B. Pritchard. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011.

- Herodotus. The Histories. Translated by Robin Waterfield. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

- Lichtheim, Miriam. Ancient Egyptian Literature, Volume II: The New Kingdom. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1976.

- Livy. The Early History of Rome: Books I–V of The History of Rome from Its Foundation. Translated by Aubrey de Sélincourt. London: Penguin Classics, 2002.

- Polybius. The Rise of the Roman Empire. Translated by Ian Scott-Kilvert. London: Penguin Classics, 1979.

- Sallust. The Jugurthine War and The Conspiracy of Catiline. Translated by S. A. Handford. London: Penguin Classics, 1963.

- Sima Qian. Records of the Grand Historian: Han Dynasty I. Translated by Burton Watson. New York: Columbia University Press, 1993.

- Tacitus. The Annals of Imperial Rome. Translated by Michael Grant. London: Penguin Classics, 2003.

- Thucydides. History of the Peloponnesian War. Translated by Rex Warner. London: Penguin Classics, 1972.

- Van De Mieroop, Marc. A History of the Ancient Near East ca. 3000–323 BC. 3rd ed. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2015.

- Xenophon. A History of My Times. Translated by Rex Warner. London: Penguin Classics, 1979.

Originally published by Brewminate, 06.18.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.