By Dr. Megan Lewis

Associate Professor, Theater History and Performance Studies

University of Massachusetts Amherst

By Dr. Marian Feldman

W.H. Collins Vickers Chair in Archaeology

Johns Hopkins University

Introduction

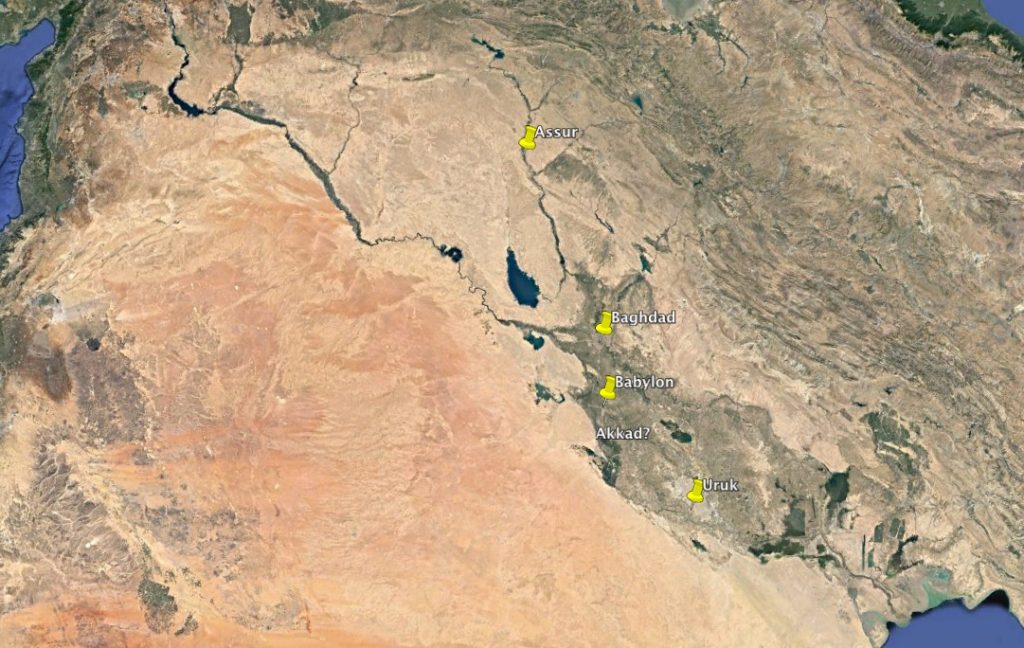

In order to understand the place of myth in Mesopotamian culture, it is first necessary to give a general introduction to Mesopotamian religion. First, there is no single Mesopotamian ‘religion.’ The region known by scholars as Mesopotamia covers a vast geographical area, and the evidence used to understand the cultures of that region come from over 4,000 years of human activity (fig. 1). Some general statements can be made, however. Religion in Mesopotamia was a highly localized and politicized phenomenon. Each city had its own patron deity, and the role of that deity was renegotiated depending on the political status of its city. For example, when Babylon rose to power during the second millennium BCE, the pantheon was rearranged so that Marduk, patron god of Babylon, was superior to all other deities (Lambert 2013: 255-56).

Second, Mesopotamian religion was not a matter of belief, in the manner of modern religions. Rather, the existence of the gods was a matter of fact, and they were considered to have their own place at the top of the social order. They also had their own hierarchy, though there were local variations. The temples were viewed as the gods’ household, with associated land and attendants who cared for the gods and their property. This included dressing and feeding the cult statues. Mythology, therefore, was not an article of faith but instead stories about the activities of the gods. These include cosmology (relating to the creation of the world and ordering of the universe) and etiological myths (myths that explain the origin of cultural activities and natural phenomena).

Cosmological Mythology

There are several myths that deal with Mesopotamian cosmology. Perhaps the most well-known is the myth Enuma Elish. ‘Enuma Elish’ is translated as ‘When on high,’ and are the first two words of the text, used as a title for the composition. This is the only systematic account of Mesopotamian cosmology, though other compositions deal with individual aspects of the creation of the world (Lambert 2013: 169). The most famous example of the text was found in the library of king Ashurbanipal in Nineveh, and dates to the 7th century BCE (Lambert 2013: 3). Enuma Elish opens with a theogony, detailing how the gods were descended from a pair of primordial deities, Apsu and Tiamat. The young gods are so noisy that they disturb Apsu, who then plots their destruction. Instead, one of the young gods, Ea, kills Apsu. In revenge for her partner’s death, Tiamat creates an army of monsters that terrifies the gods so badly that they search for a hero to save them. Finally, Marduk, the youngest of the gods, agrees to take on Tiamat and the demons in return for being made king of the gods. He is victorious, and then proceeds to create heaven and earth out of Tiamat’s body (fig. 2). Marduk then creates the stars, constellations, and phases of the moon, and from the blood of Tiamat’s defeated general, Marduk also creates humanity in order to work for the gods (fig. 3). The gods build the city of Babylon and temples and shrines within the city, and the text ends with a recitation of the fifty names of Marduk.

This text both explains how the world came into being and mythologizes Babylon’s place as the new political power in Mesopotamia. As stated above, Babylon rose to power during the second millennium BCE. As the patron deity of Babylon, Marduk rose from being just another city deity to the head of the pantheon (Lambert 2013: 277). This same phenomenon can be seen in the later Assyrian version of Enuma Elish, in which the chief god of the city Assur takes Marduk’s place in the myth (Lambert 2013: 4-5). Enuma Elish was recited at the Babyonian New Year’s festival as an important part of the most critical religious festival of the Babylonian calendar. The so-called ‘Babylonian Map of the World’ provides further evidence for the localized nature of Mesopotamian cosmology, placing Babylon firmly at the center of the world (fig. 4).

An alternative cosmology can be seen in the myth known as Atrahasis. In this myth, the lesser gods revolt against Enlil and refuse to continue doing manual labor. In a similar manner to the events in Enuma Elish, humanity is created out of the blood of a sacrificed god in order to perform their work. Other similarities to Enuma Elish include a part in which the newly-created humans make so much noise that the gods plan to destroy them in order to get some peace. Their plans are repeatedly foiled by the god Enki and his human servant, Atrahasis. After a flood similar to the one recounted in the Hebrew Bible book of Genesis, dry land is found, and Atrahasis institutes the practice of giving offerings to the gods. The composition concludes with the gods’ plans to limit human reproduction, including celibate positions in the priesthood, and a demon called Lamashtu to carry off children (fig. 5).

Etiological Mythology

As seen in the origin of offerings to the gods found in Atrahasis, Mesopotamian mythology could provide etiological explanations for cultural practices. One of the best examples is the myth known as Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta, in which king Enmerkar and his rival from Aratta engage in a competition for the affections of the goddess Ishtar. As part of the competition, Enmerkar writes a message on a clay tablet and sends it to Aratta, inventing writing in the process (fig. 6, 7). As the lord of Aratta cannot read the written message, he loses the competition and Enmerkar’s city, Uruk, is declared the goddess’ favorite city.

Another etiological myth is Enki and the World Order, in which the god Enki assigns responsibilities to individual gods, and decrees the fates for temples and cities. For example, the Tigris River is said to be created by the god ejaculating (Enki and the World Order 250-258). The myth known as Inanna’s Descent to the Netherworld can also be understood as an etiological explanation of the seasons. In this myth, the goddess Inanna travels to the netherworld and is captured by her sister and queen of the netherworld, Ereshkigal. The god Enki engineers her escape, but a substitute is demanded in return for Inanna’s freedom. Inanna’s husband, the god Dumuzi, is taken in her place and must stay in the netherworld for half of every year (fig. 8). Dumuzi was a god of vegetation, and his 6-month absence from the world can be understood as an explanation for the dying of crops during the hot summer months (Sladek 1974: 27). As the god of vegetation dies each year and is condemned to the underworld, the crops and vegetation that he commands also die until he returns to the land of the living.

‘Political’ Mythology

As seen from the different variants of Enuma Elish, Mesopotamian mythology also took on a political aspect. The political nature of mythology can be seen even more clearly in myths that feature historical figures as their main characters. These include The Birth Legend of Sargon of Akkad and the Cuthaean Legend of Naram-Sin. The Birth Legend gives a mythologized account of how Sargon of Akkad (c. 2300 BCE) rose from a non-royal background to become king (fig. 9). The composition includes a theme that may be familiar to modern readers – Sargon is described as the son of a high priestess, who put him in a reed basket and left him in a river when he was a baby, a motif that is very similar to the story of Moses. Sargon is then found by a farmer and raised as a commoner, ignorant of his parentage. Though Sargon of Akkad reigned in the 3rd millennium BCE, it is challenging to ascertain a date of composition for The Birth Legend. The extant copies of the text are from a relatively late period in Mesopotamian history, sometime in the 1st millennium BCE, but whether this was also the point at which the text was composed, or if the copies we have are later reproductions of a text originally written sometime in the 2nd millennium is difficult to determine (Foster 2013: 912; Lewis 1980: 97). One suggestion is that The Birth Legend was composed during the reign of Sargon II of Assyria (c. 721-705 BCE; Lewis 1980: 104-107). Lewis notes significant correlations between the historical accomplishments of Sargon II and those attributed to Sargon of Akkad in The Birth Legend, and suggests that the text was intended to celebrate the present king (Sargon II) by showing that he was a suitable successor to Sargon of Akkad, whose empire-building was admired by later Assyrian rulers (Lewis 1980: 102, 106). Sargon II’s accession to the throne also appears to have been irregular – he was the son of the Assyrian king, Tiglath-Pileser III, and probably took the throne from his brother, Shalmaneser V, the rightful heir (Lewis 1980: 103). By providing a legitimate, mythological precedent for usurpation, and by connecting himself to the earlier king through a shared name, Sargon II may also have been trying to give legitimacy to his own rule (Lewis 1980: 103).

Another example of politicized mythology is the Cuthaean Legend of Naram-Sin. This narrative seems to take historical events and mythologize them, turning a series of battles faced by king Naram-Sin, the grandson of Sargon of Akkad, into divine judgment against the king (Foster 2005: 344). This myth is known from three versions from the Old Babylonian period (1894-1595 BCE), the Middle Babylonian period (1595-1155 BCE), and the Late Assyrian period (911-612 BCE). In all versions, Naram-Sin faces an undefeatable enemy that continually decimates the troops he sends out against it (LA 80-90). The later versions describe the enemy force as agents of the gods – Ea (MB 5’-10’) or Enlil (LA 130-135). The Late Assyrian and Middle Babylonian versions also both blame the suffering of Naram-Sin upon his predecessor, Enmerkar, as he did not write an account of his own trials for future kings to read and thereby avoid making the same mistakes. The Late Assyrian version is more explicit about exactly what this mistake is, describing how Naram-Sin ignored the results of seven extispicies – omens taken from the liver of sheep, which were considered instructions from the gods (fig. 10). In ignoring these messages, Naram-Sin showed himself to be arrogant and impious, thus deserving of his fate. This theme of Naram-Sin as an impious king may be a later remembering of religious changes that happened during his reign, including his self-deification and the reduction of gods on public monuments from active figures to astral symbols only (fig. 11).

Incantations and Mythology

As well as explaining the origins of natural phenomena and cultural practices, Mesopotamian myths appear to have had a more practical purpose and were used to cure and prevent various physical ailments. For example, an amulet made to protect the owner against plague displays this purpose, as it was inscribed with a section of the myth Erra and Ishum (fig. 12). Mesopotamian incantations can also contain mythological elements, giving further evidence for the efficacious nature of mythology in Mesopotamian society. One excellent example of this is the Incantation Against Toothache (fig. 13). The incantation gives a truncated cosmogony that starts with the god, An, creating the sky, and ends with the creation of a worm by the marshland. The worm then begs the god Shamash to give him something to eat, requesting that he be placed between a person’s teeth and jaw so he can eat stray food and suck on the blood in the jaw. The worm is seen as the root of the toothache, and the incantation ends with the wish that the god Ea strike the worm, ending the patient’s suffering.

Representing Mythology

Intriguingly, there is a general lack of mythology represented in art for reasons that still elude us. Images of deities are relatively common, though these can be difficult to securely identify, and no cult statues have survived in the archaeological record.

The Queen of the Night plaque is an excellent example of the challenges surrounding the interpretation of mythological artwork (fig. 14). Though the plaque is a mostly-complete piece and the scene it depicts is very clear, scholars are unsure which goddess it depicts. The goddesses Ishtar and Ereshkigal are both possibilities, but the plaque’s iconography does not completely fit with Ishtar, and Ereshkigal’s iconography is unknown (Collon 2005: 42-43, 45). The best that can be said is that the plaque depicts a female deity, as she wears the horned crown characteristic to the gods.

Actual scenes from mythology are comparatively rare, though one of the few that can be securely identified is a motif occasionally found on cylinder seals that is thought to depict a scene from a myth about a king named Etna, who flew to heaven on the back of an eagle in order to try to obtain an heir. The seals generally show a male figure on the back of a flying eagle, with additional figures filling in the space on the seal (fig. 15).

Another possible representation of a mythological figure are the so-called ‘Humbaba masks,’ which may depict the monster Humbaba from the Epic of Gilgamesh (fig. 16). In the myth, the heroes Gilgamesh and Enkidu kill the monster Humbaba and cut off his head. The Humbaba masks seem to depict the severed head, Humbaba’s face frozen in a grimace or composed of coiled entrails. As some examples found are pierced (possibly to be hung on a wall), they have been argued to have apotropaic qualities (fig. 17, Moorey 1975: 88).

In contrast to the infrequency of mythological representations, religious activity is depicted with some regularity in art, as are demons and spirits (figs. 18-20).

Bibliography

- Bottéro, J. 1992. Mesopotamia: Writing, Reasoning, and the Gods. Trans. Z. Bahrani and M. Van de Mieroop. Chicago, IL and London.

- Collon, D. 2005. The Queen of the Night. London.

- Foster, B. 2005. Before the Muses. Third edition. Bethesda, MD.

- Lambert, W. G. 2013. Babylonian Creation Myths. Winona Lake, IN.

- Lewis, B. 1980. The Sargon Legend: A Study of the Akkadian Text and the Tale of the Hero who was Exposed at Birth. Cambridge, MA.

- Moorey, P. R. S. 1975. ‘The Terracotta Plaques from Kish and Hursagkalama, c. 1850-1650 B.C.’, in Iraq, vol. 37, no. 2, pp. 79-99.

- Sladek, W. R. 1974. Inanna’s Descent to the Netherworld. Baltimore, MD.

- Van de Mieroop, M. 2007. A History of the Ancient Near East, ca. 3000-323 BC. Second edition. Chicago, IL and London.

Originally published by Rice University, OpenStax CNX, 09.27.2016,, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 license. Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/382608d7-c0df-4413-897a-06252a785b7c@1.