By Mark Cartwright

Historian

Introduction

A censor was one of two senior magistrates in the city of ancient Rome who supervised public morals, maintained the list of citizens and their tax obligations known as the census, and gave out lucrative public contracts and tax collecting rights. The title is the origin of the modern related terms ‘censor’ and ‘censorship’ as censors could mark down and remove people from the citizen list. The office was terminated c. 22 BCE, with its powers going to the emperor or redistributed to other officials.

Position and Evolution

The position of censor was, according to Livy, established in 443 BCE. They were elected every four or five years by the comitia centuriata, the assembly of Rome with a wealth qualification for members. They held a term of 18 months. In 339 BCE, after a century of tradition where only those of the aristocratic patrician class could hold the office, the legesPubliliaedecreed that one of the two censors must be of the lower plebian class. In 131 BCE two plebeians held both offices for the first time. Following Sulla’s reforms, in 81 BCE, the importance of the position was reduced and their election became less regular. In the Imperial period, the emperor largely took over the powers which had been in the hands of the censors and no censor was elected after 22 BCE.

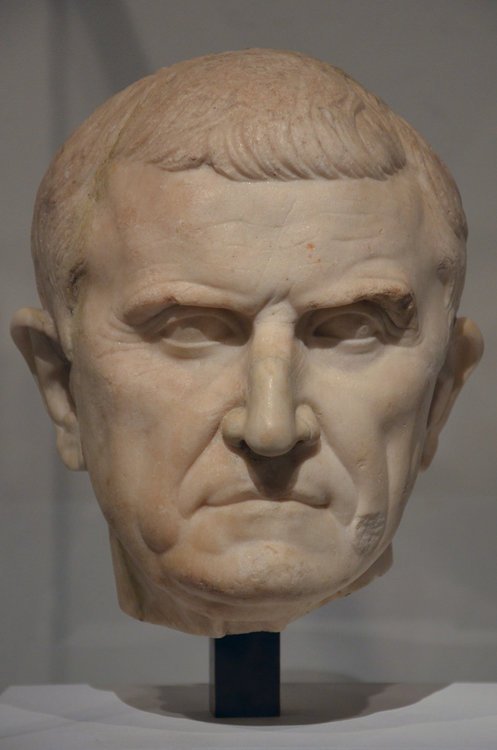

Although the political power of the censors as defined by law was actually limited – they were not granted imperium (the right to interpret and execute law or to command in war) – and they did not have an escort of lictors carrying the symbolic fasces as with other magistrates, their views and actions often carried weight due to the experience of the office holder and the prestige attached to the office itself. Indeed, the title of censor was regarded as the highest in the cursushonorum or Roman public career path. A convention developed whereby only former consuls were eligible for the office. As an example of the powerful figures who held the position, Cato the Elder was censor in 184 BCE, and Marcus Licinius Crassus, probably Rome’s richest ever man, was made censor in 65 BCE between his two stints as consul.

The Census

The censors were responsible for carrying out, every four or five years, the national census which was a list of all the citizens in Rome and the provincial towns, what their tax obligations were, and what their liability for military service was. Previously this had been the duty of the tribunes. The census included an individual’s full name, age, father’s name, where they lived, their job, and how much property they had. Women and children were not included except as dependents. The censors organised the names into tribes and centuries according to five different classes based on the equites knight class, levels of property or no property.

The censor could mark (with a nota) any name on the list which would exclude that person from their tribe and prohibit them from voting, i.e: censor them. An individual marked down in such a way became an aerariusand still had to pay taxes even if they could not now vote. One of the reasons a censor might do this is because a citizen had done something immoral in their public or private life and so the office came to be associated with maintaining the moral standards or rRegimen morum within the community.

When the census was complete, one of the censors (chosen by lot) performed a religious ceremony known as thelustratio on the Campus Martius of Rome. Here prayers, animal sacrifices and a purification by fire kept away evil and ensured success for the coming year.

Other Duties

It was also the censor’s job to ensure the membership of the Roman Senate was in order. Besides selecting senators they could also exclude individuals, again for reprehensible behaviour. With Sulla’s reforms, the selection process for the Senate was changed and any citizen holding quaestor rank automatically qualified. Another similar function of a censor was to record who of the equites held the public horse, and once again, for anyone they deemed unsuitable, their horse could be confiscated and the individual barred.

Other duties of the censors included leasing public property, including mines, forests, and rivers which could generate revenue; supervision of public works projects such as road building, libraries, and Roman baths; and forming contracts with the public contractors (publicani) who collected provincial and harbour taxes (portoria) and any revenue from public property (vectigal). There were sometimes problems with this system as censors had tremendous fiscal power to sell contracts to the highest bidder, sometimes even auctioning off the right to collect taxes for entire provinces. This led to conflicts of interest, competition between censors, and a general abuse of office.

There were also less defined powers such as the granting of citizenship to foreigners. In an example of the latter case, we know that Crassus, while censor, granted citizenship to the Transpadanes in Cisalpine Gaul, an unpopular move and one of the reasons for his removal from office. Cato the Elder, who actually became widely known as ‘Cato the Censor,’ famously introduced a tax on luxury in order to quell the decline in morality he saw in 2nd-century BCE Republican Rome.

Legacy

Although the office of censor was suppressed in the imperial period, the taking of the census continued well after. Augustus carried out three during his long reign, and the last known census in Italy was conducted c. 80 CE, after which statistics for tax and voting rights were no longer relevant as the former came from the provinces where governors became responsible for updating them. Roman Egypt was noted for its regular 14-year census, and several examples of censuses carried out across the empire are preserved on papyri. As the historian Peter Fibiger Bang notes, ‘it was far from a negligible instrument of state power and continued to provoke resistance down the ages’ (Barchieis, 676). The practice of control through statistics also outlasted the Romans themselves as many modern states continue to conduct a census at regular intervals to gather figures on their ever-changing populations.

Bibliography

- Bagnall, R.S. The Encyclopedia of Ancient History. (Wiley-Blackwell, 2012)

- Barchiesi, A. The Oxford Handbook of Roman Studies. (Oxford University Press, 2010).

- Grant, M. The History of Rome. (Faber, 1997)

- Hornblower, S. The Oxford Classical Dictionary. (Oxford University Press, 2012).

Originally published by the Ancient History Encyclopedia, 03.15.2017, under a Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.