An informed understanding of The Federalist’s references to ancient Rome.

By Louis J. Sirico, Jr., J.D.1

Professor of Law

Charles Widger School of Law

Villanova University

Introduction

In The Federalist, John Jay, Alexander Hamilton, and James Madison wrote to persuade their readers to support ratification of the proposed Constitution.2 In their eighty-five newspaper essays, they attempted to explain the wisdom of every provision of the Constitution and defend the document against every criticism. In the first of these papers, Hamilton, sets out their purpose:

I propose in a series of papers to discuss the following interesting particulars–The utility of the UNION to your political prosperity–The inefficiency of the present Confederation to preserve that Union–The necessity of a government at least equally energetic with the one proposed to the attainment of this object–The conformity of the proposed constitution to the true principles of republican government–Its analogy to your own state constitution–and lastly, The additional security, which its adoption will afford to the preservation of that species of government, to liberty and to prosperity.3

In making the argument, Publius, the collective pen name of the three coauthors, draws lessons from experiences of other countries, including the classical civilizations. For example, a glance at an index to The Federalist would disclose 14 references to Rome and 11 to Greece.4 Newspaper readers of that day apparently would easily understand these references.5 However, the modern reader would find most of them quite obscure. Except for classicists, few modern readers, for example, would know about the dictatorship of the Roman decemvirs or the popular assemblies of republican Roman, such as the comitia centuriata and comitia tributa.

Since the time of the Constitution’s framing and ratification, our intellectual canon has changed. In that earlier era, for example, readers would have understood why the authors of The Federalist would have chosen the pseudonym of Publius. The pen name was a reference to Publius Valerius, known to the Roman people as “Publicola” (lover of the people) who helped found the Roman republic after the overthrow of the Tarquinian line of kings.6 Today, few readers would appreciate the reference. Ancient history is no longer central to American. education and culture.7

The shift in the American canon may impede our understanding of the Framers and their work. A lack of information may result in more than failing to grasp an analogy buried in an essay. To understand a historical analogy fully, the reader needs historical context. Otherwise, the reader may discern the essence of the analogy, but fail to appreciate its full meaning. For example, in reading Federalist No. 70, the reader might puzzle over this sentence: “The Decemvirs of Rome, whose name denotes their number, were more to be dreaded in their usurpation than any ONE of them would have been.”8 By reflecting on the surrounding sentences, the reader might determine that Hamilton is arguing in favor of having a single executive, rather than several executives sharing power, because he believes that a multiple executive is more likely to be enticed into tyranny than a single executive. If the reader knows nothing of Roman history, he or she may surmise that the decemvirs were a group of leaders similar to a multiple executive. However, if the reader enjoyed a deeper understanding of history, he or she would know that in the fifth century, B.C.E., the patricians capitulated to the plebeians’ demand for a codified law that would rein in the discretion of the patricians in administering law.9 The patricians appointed ten men, the decemvirs, to draft the laws and to have complete power over the state for one year. However, after one year, the decemvirs succeeded in gaining another year in which to complete the project. After the second year, the decemvirs still did not relinquish their power. Eventually a scandal forced them out. A reader who has the knowledge or, better yet, knows an even more complete version of this story could fully understand Hamilton’s argument: Even officials appointed to assume civic responsibility for an important task can be tempted into becoming tyrants.

As another example, a modern reader of Federalist No. 41 would encounter this statement: “No less true is it that the liberties of Rome proved final victim to her military triumphs . . . .”10 From these words, the reader might discern that Madison fears the interference of the military in civic affairs. The surrounding sentences might disclose that the particular issue is whether the proposed Constitution was prudent in authorizing a standing army.11 As a proponent of the Constitution, Madison has to argue that despite the dangers of a standing army, it is necessary for self defense and that the Constitution provides a check on military power by providing that Congress can appropriate revenues to support the army for a term of no longer than two years.12 However, only with knowledge of Roman history can the reader understand why Madison’s contemporaries would view a standing army with great trepidation: Rome’s standing army became such a powerful force that it installed and murdered emperors with some regularity.13

This Article seeks to assist today’s reader in gaining the historical context necessary for an informed understanding of The Federalist’s references to ancient Rome. The Article explains each significant reference to Rome with a somewhat simplified, but nonetheless richly textured historical background for the reference.

The Article begins with a brief outline of the history of republican Rome, the era to which Publius makes most of his Roman references. The outline gives the reader enough history to follow the discussion that follows. The Article then organizes the Roman references under four arguments that Publius makes: the need for a national government, the need for a single executive, the best way to structure a government, and the need for a standing army. The Article concludes with brief reflections on the extent to which these classical references were persuasive to Publius’ readers, what the references tell us about how the Framers viewed Roman history, and, in light of our fading familiarity with classical Rome, on what political references do modern commentators rely.

The Roman Republic: A Historical Outline

As might be expected, the history of Rome’s early years depends more on legend than on verifiable fact.14 Rome’s story begins on the Latium plain along the Tiber river. In ancient times, the city of Alba Longa boasted a line of kings that extended back to Anaeas, the Trojan hero. In the eighth century, B.C.E., Amulius usurped the throne of his elder brother Numitor. However, Rhea Silva, Numitor’s daughter, then had twins, fathered by Mars. The twins, Romulus and Remus were placed on a raft, which eventually landed on shore. The twins were then raised by a she-wolf. When they came of age, they killed Amulius, restored Numitor to the throne, and set out to found their own city.

In 753, Romulus quarreled with his brother and killed him. He then proceeded to build the city of Rome. After Romulus’ death in 717, the city was ruled by a series of kings, ending with the line of Tarquinian kings. The line ended when Lucius Tarquinius (Surperbus) turned the kingship into an absolute monarchy and consequently was deposed by the patricians, led by Lucius Junius Brutus.

With the end of the Tarquinian line in 509, the republican era began, and its political structure gradually took shape. In addition to the patrician senate, all Romans belonged to another assembly, the patrician-dominated comitia centuriata; however, the senators effectively exercised a veto power over its decisions. Among its other functions, this assembly appointed two consuls to head the state and the army. Each consul could veto the proposals of the other. Not until 367 could a plebeian hold this office.

After several class conflicts between the patricians and plebeians, the plebeians gained permission to elect tribunes who would represent them before the senate and consuls and who would have the power to veto any law that the consuls proposed.

The plebeians also demanded the security of a written code of laws, and, in 451, ten men, the decemviri were chosen to write the code. While completing the project, they would enjoy absolute political power. The decemviri codified Roman customary law on twelve tablets. However, when they finished their work, they refused to relinquish their political power until they were forced to resign. Still, during the life of the republic, conflicts between patricians and plebeians continued with the patricians generally continuing their domination.

During the ensuing centuries, Rome conquered Italy and many foreign lands. Perhaps the most notable military events were the three Punic Wars against Carthage, the African city and Mediterranean trading empire (264-241, 218-202, 149-146). At the end of the third war, the Romans demolished Carthage and ploughed salt into the ground to prevent it from rising again.

Intertwined with the Second Punic War was Rome’s struggle with the Hellenistic Empires. Philip V of Macedon had allied himself with Carthage. Afterward, he refused to agree to stop seizing Greek territories, and, in 196, the Romans quickly defeated him. Meanwhile, Antiochus III of the Seleneid Empire continued his aggressions against the Greek cities until, in 189, he also met defeat at the hands of the Romans. However, Philip’s successor, Perseus then became active in Greece, only to meet the same feat as Antiochus.

Particularly after the second Punic War and the Macedonian wars, the divide between rich and poor increased dramatically. The growing conflict came to a head in 133 when Tiberius Gracchus became a tribune and proposed massive land reform. His efforts led to political conflict and ultimately to a riot in which a group of senators clubbed him to death. In 124, his brother Gaius was elected tribune and also attempted to implement reforms. Although he met with some success, the resulting conflicts ended in bloodshed and Gaius’ death .

The ensuing years brought a war in Africa, an attempted invasion by German tribes, and civil war in Italy. Marius and Sulla, two popular generals, became political rivals and, with their military forces backing them, took turns controlling Rome and slaughtering those who opposed them. Rome was left with a corrupt government.

The republic was to end with the rise of Julius Caesar. In the early years of his political career, Caesar joined forces with Pompey, another military hero, and Crassus, also a military leader and an extremely wealthy man. While Caesar was away from Rome, conquering the Gauls and Germans, Pompey remained in the city consolidating political power. Meanwhile, Crassus was killed while fighting the Parthians in Spain.

Pompey and Caesar were now rivals. When Caesar returned from Gaul, Pompey had withdrawn to mobilize his troops. After compelling the senate to declare him dictator, Caesar pursued and defeated Pompey. When Caesar eventually returned, he restored order and, in 44, became dictator for life. Yet, within five months, he was assassinated by senators who hoped for a return to the republic and patrician power.

By 29, Caesar Augustus (formerly named Octavian), the grandson of Caesar’s sister and Caesar’s adopted son, had conquered all rivals. Although he retained the republican governmental institutions, at least nominally, he had initiated the era of the Roman Empire.

The Need for a National Government

Overview

In arguing against continuing a loose confederation of states and establishing a vital national government, Jay, Hamilton, and Madison looked to Roman history for examples of the dangers of a confederacy. They argued that (1) confederation members inevitably end up in conflict; (2) these conflicts can result in anarchy; and (3) confederations increase the risk of individual members forging foreign alliances that could lead to foreign domination.

The Inevitability of Internal Disputes: Rome’s Conflicts With Its Neighbors

To look for a continuation of harmony between a number of independent unconnected sovereignties, situated in the same neighbourhood, would be to disregard the uniform course of human events, and to set at defiance the accumulated experience of the ages.

The genius of republics (say they) is pacific; the spirit of commerce has a tendency to soften the manners of men, and to extinguish those flammable humors which have so often kindled into wars. Commercial republics, like ours, will never be disposed to waste themselves in ruinous contentions with each other. They will be governed by mutual interest, and will cultivate a spirit of mutual amity and concord.

Sparta, Athens, Rome, and Carthage were all Republics; two of them, Athens and Carthage, of the commercial kind. Yet were they as often engaged in wars, offensive and defensive, as the neighboring monarchies of the same times. Sparta was little better than a well-regulated camp; and Rome was never sated of carnage and conquest.

Carthage, though a commercial Republic, was the aggressor in the very war that ended in her destruction. Hannibal had carried her arms into the heart of Italy and to the gates of Rome, before Scipio, in turn, gave him an overthrow in the territories of Carthage and made a conquest of the Commonwealth.

From this summary of what has taken place in other countries, whose situations have borne the nearest resemblance to our own, what reason can we have to confide in those reveries, which would seduce us into an expectation of separation? – Alexander Hamilton, Federalist No. 615

Here, Alexander Hamilton argues for a unified government, and expresses his skepticism about the pacific instincts of the current confederation of states. According to Hamilton, a nation (or state) is inevitably drawn into conflict with its neighbors. Moreover, even though states are not ruled by monarchs, their current governmental structures will not lessen the chances of hostility among them. As history shows, even republics are prone to falling into conflict with their neighbors. A united American republic, on the other hand, will encourage peace among the states far better than would the present confederation.

Ancient Rome could chronicle a long history of conflict with its neighbors.16 Shortly after the destruction of the monarchy in 509 B.C.E., Rome concentrated not only on creating the new republic, but also on conquering its Italian neighbors. In fact, during the first one hundred years of the republic, almost every summer witnessed a Roman military campaign against its Italian neighbors. For instance, in 396, Rome laid siege to the Etruscan city of Veii. This struggle between the Romans and Etruscans was constant in Rome’s first centuries. By 275, the Romans exercised control over the entire Italian peninsula, with its northern border at the Po Valley. Moreover, this Roman expansion was achieved more by its military resources than its diplomatic efforts.

Yet Rome itself did not remain unscathed in the early years of the republic. For years, Gallic barbarians were moving out of their homelands in central Europe and into areas like France, Spain and Britain. When they reached the Po Valley, they began to raid Italian lands, traveling as far as central Italy. Rome sent out an army to quell this threat; however, the force faced annihilation at the Allia river. The Gauls continued their march south and, in 392, sieged and sacked Rome. The city itself was almost completely destroyed, and the Gauls left only after being pushed out by Camillus, a Roman patrician who was elected emergency dictator by the curiate assembly.

This near disaster, however, failed to deter Roman bellicosity. Instead, warfare became a part of Roman culture, and it was rare for a year to go by without Rome engaging in a war. The doors of the temple of Janus, erected by Numa Pompilius, were to be closed whenever Rome was at peace. However, those doors were closed for only two short periods during the republican era: in 24, after the consulship of Manlius following the First Punic War, and, in 29, under the reign of Caesar Augustus at the end of the republican era.

As Rome’s domination over Italy became unassailable, Rome began to look abroad for new foes. During the age of the republic, Rome would engage in military campaigns against virtually every civilization bordering on the Mediterranean Sea. By 54, Roman military ambition had reached as far north as Southern Britain.

Among the most famous of Rome’s many military campaigns were its wars against its neighbor Carthage in North Africa, in present-day Tunisia. Over the course of one hundred and twenty years, Rome and Carthage would engage in three costly wars known as the Punic Wars. The First Punic War was sparked in 264, when the Mamertines, a group of Italian mercenaries, invaded the island of Sicily. The Sicilian authorities requested aid from both Carthage and Rome. Carthage agreed to come to the rescue of the Sicilians; however, the Romans felt that their loyalties rested with the Mamertines and supported them. Inevitably, Rome came to blows with the Carthaginians, and, in 241, Roman naval forces decisively defeated Carthaginian forces at the Aegates Islands.

By 226, Carthage had attempted to expand its empire by establishing a strong foothold in Spain. In that year, Rome imposed a limitation on Carthaginian eastward expansion in Spain by setting the boundary of Carthage’s expansion at the Ebro River. Hannibal, the Carthaginian general in Spain, was angered by this Roman imposition. In 219, he attacked the city of Saguntum, which was an ally of Rome. Despite pleas from Saguntum, Rome did not come to its aid, and after an eight-month siege, the city fell to the Carthaginians. After the fall of Saguntum, Rome sent ambassadors to Spain demanding the surrender of Hannibal. However, Carthage would not acquiesce to this demand, and, in 218, the Second Punic War officially commenced.

The early stages of the war went very badly for Rome, as Hannibal brought his army and elephants through the Alps and into Italy in their famous march. However, in 216, the war would reach its most devastating point for Rome when Hannibal annihilated the Roman army at Cannae in Eastern Italy. In the course of the battle, 25,000 Romans would be killed, and 10,000 would be captured, including one Roman consul, Terentius Varro. The other Roman consul, Aemilius Paullus, was among the dead at Cannae. Thus, in the course of this one battle, Rome lost both its high magistrates and the army on which it depended to defend the Italian peninsula. However, Carthaginian fortunes soon turned around however, as the young Roman general Scipio Africanus, launched a campaign on Carthage itself and, in 202, defeated Hannibal at Zama. This Roman victory forced Carthage to once again surrender to Rome and pay the reparations of 10,000 gold talents as well as surrender all their war elephants and disassemble their navy.

The Roman-Carthaginian hostilities, however, did not end in 202. Many Romans maintained that insuring a lasting peace required the destruction of Carthage. The most notable advocate of this position was Cato the Elder, who after every speech before the Senate proclaimed, “Carthage must be destroyed.” This view gained popular acceptance in Rome, and the Romans began to seek armed conflict with Carthage and its African neighbors. In 149, the two republics commenced their third war, and, after the city of Carthage fell, Roman forces razed the city to the ground and salted the earth to make the land uninhabitable.

Rome’s conflicts were not limited to conquest or self-defense; through bouts of civil war, the republic also suffered carnage. The Roman Social War (91-88) and the conflicts that followed serve as excellent examples of the Roman penchant for civil war. The Social War was a result of years of non-Roman Italians being dissatisfied with their statue as quasi-citizens of Rome. The various inhabitants of Italy were granted some of the benefits of Roman citizenship, but not complete citizenship with full benefits. In 91, Livius Drusus, a Roman demagogue, suggested that all Italians should receive Roman citizenship. As a result, he was assassinated, and his proposal was rejected by the Senate. These events sparked a revolt amongst the Italian tribes of the Samnites and the Marsi, and Cornelius Sulla and Gaius Marius set out with Roman legions to pacify the rebels.

Although these two generals were able to quell the insurrection, they nevertheless would do more harm than good for the republic through their competition with one another. In 88, Sulla was elected consul and received the command of a Roman army to fight Mithradates in Asia. While Sulla was away on campaign, Marius seized control of Rome and had some of Sulla’s allies killed. Marius then died, leaving his supporters in power. In 83, Sulla returned from the east and set about placing Rome back under his rule. Sulla took his army and marched on Rome, where, in a vicious battle outside the Colline Gate of Rome, Sulla defeated the forces of Marius’ followers and regained control of the city. Sulla then proclaimed himself dictator of Rome and compiled a list of names of those who were disloyal to him during his absence. These lists, known as proscriptions, awarded monetary sums to those who presented Sulla with the heads of those who had been proscribed. In 78, Sulla died, and the republic briefly returned, to the governmental form it possessed prior to 88.

Very shortly afterward, Gaius Julius Caesar, a young general and politician, would once again plunge Rome into civil war. After a political falling out with his one time friend and coruler, Pompey the Great (Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus), Pompey secured a decree of martial law and had himself declared sole-consul. Meanwhile, Caesar was stationed in Gaul in charge of an army and aware that he would be subject to prosecution in Rome for the illegal passage of legislation when he was consul in 59. In order to avoid this fate, Caesar instead mobilized his army and led them across the Rubicon River, which separated Cisalpine Gaul from Italy. With this move, Caesar had declared war on the government by bringing his armed soldiers out of Gaul and into Italy without permission. Caesar quickly destroyed the opposition he met in Italy and forced Pompey to flee to Greece. In 48, at Pharsalus in Thessaly, Caesar defeated Pompey’s forces in battle and caused Pompey to flee to Egypt. Pompey was subsequently assassinated by agents of King Ptolemy XIII of Egypt, an ally of Caesar’s.

The civil war, however, did not end with the death of Pompey and the appointment of Caesar as dictator. Caesar then began chasing the children of Pompey and their armies across the Mediterranean basin. In 46, Caesar took his army to North Africa, where some of Pompey’s followers remained and defeated them on the battlefield at Thapsus. The survivors fled to Spain where Caesar won a decisive victory against the Pompeians at the battle of Munda, effectively ending the civil war and allowing Caesar to return to Rome and rule until his assassination in 44.

In Federalist No. 6, Hamilton warns that neighboring states tend to enter into conflict. He suggests that in order to avoid such disaster in the new nation, the states should not continue as a confederacy, but should form a union, effectively subjecting all the States to one government and decreasing the chances of war among them. As Hamilton argues, such conflicts were common with Rome and its neighbors. Nonetheless, Hamilton ignores the Roman republic’s propensity to fall into civil wars as well as external wars. This problem of civil war would come to divide the United States less than a century later.

The Threat of Anarchy Among Confederation Members: The Macedonian War

Had Greece, says a judicious observer on her fate, been united by a stricter confederation, and persevered in her Union, she would never have worn the chains of Macedon; and might have proved a barrier to the vast projects of Rome.

Philip, who was now on the throne of Macedon, soon provoked by his tyrannies, fresh combinations among the Greeks. The Achaeans, though weakened by internal dissensions and by the revolt of Messene one of its members, being joined by the Etolians and Athenians, erected the standard of opposition. Finding themselves, though thus supported, unequal to the undertaking, they once more had recourse to the dangerous expedient of introducing to the succour of foreign arms. The Romans to whom the invitation was made, eagerly embraced it. Philip was conquered; Macedon subdued. A new crisis ensued to the league. Dissentions broke out among its members. These the Romans fostered. Callicrates and other popular leaders, became mercenary instruments for inveigling their countrymen. The more effectually to nourish discord and disorder, the Romans had, to the astonishment of those who confided in their sincerity, already proclaimed universal liberty throughout Greece. With the same insidious views, they now seduced the members from the league, by representing to their pride the violation it committed on their sovereignty. By these arts this Union, the last hope of Greece, the last hope of antient liberty, was torn to pieces; and such imbecility and distraction introduced, that the arms of Rome found little difficulty in completing the ruin which their arms had commenced. The Achaeans were cut to pieces; and Achaia loaded with chains, under which it is groaning at this hour.

I have thought it not superfluous to give the outlines of this important portion of history, both because it teaches more than one lesson and because, as a supplement to the outlines of the Achaean constitution, it emphatically illustrates the tendency of federal bodies rather to anarchy among members than to tyranny in the head. – James Madison, Federalist No. 1817

In this paper, Madison recounts events occurring in Greece in the third and second centuries B.C.E.18 His purpose is to demonstrate that confederations of states more commonly slip into anarchy than fall under the rule of a tyrannical government. Madison uses the Achaean example in order to show his readers the dangers of a loose confederation of states and argue that the most secure form is a unified government under a constitution.

In 281, a group of four city-states banded together to revive the long since dissolved Achaean League. The number of cities within this confederation of states grew over the years until its membership included Dyme, Patrae, Tritraea, Pherae, Aegion, Bura, Ceryrea, Argos, Megalopolis, Corinth, Pellene, Olenos and Sparta. The religious center of the Achaean League rested at the temple of Zeus Amarios in Aegion. Here the assembly of the League gathered four times each year to hold meetings (Synodoi). At the head of this assembly were the eleven members of the executive board (Synarchiae), who were the true rulers of the confederation. Because this small group of men held almost exclusive power, the Achaean League can best be described as an oligopoly.

Before the end of the Second Punic War in 201, Rome had little fear of the Greek citystates or leagues. However, Hannibal’s near-conquest of Rome after his crushing defeat of the Romans at Cannae in 216, opened the Senate’s eyes to the need to defend Rome from the threat of outside invasion. As a result, Rome began to adopt a strategy of defensive imperialism, which called for Roman control over any regions that could potentially pose a threat to Rome.

After Attalus I, the king of Pergamum, and a delegation from the trading center of Rhodes warned Rome of a secret pact between Philip V of Macedon and Antiochus III of Syria and asked for Rome’s assistance, Rome began to take a considerable interest in Greek affairs. The Roman Senate saw a possible threat to Roman soil if this alliance were allowed to gain power. Thus, in 200, Rome followed its newly emerging strategy of defensive imperialism and turned its attention to Philip.

Rome first gave Philip an ultimatum to restrain himself from attacking Greek or Egyptian cities or else face war. Philip refused, and the Second Macedonian War officially commenced. At the same time, Rome sent envoys to Antiochus assuring him that it did not intend to begin any aggression against him in Syria. This statement was designed to prevent Antiochus from having any reason to join forces with Philip in Macedon.

With Antiochus out of the way, Rome was free to engage Philip and ultimately defeat him in 197 in Thessaly at the battle of Cynoscephalae. Philip then fled to Macedon and sought peace with Rome. Strangely, in the wake of the Greek campaign, Rome did not occupy or annex any Greek land.

Rome had other plans for Greece. In 196, T. Quinctius Flamininus, the Roman consul and Roman general at Cynoscephalae, proclaimed that regions once under Macedonia’s domination were now independent; he thus freed the Corinthians, Phocidians, Locrians, Euboeans, Phthiot Achaeans, Magnesians, Thessalians and Perrhaebians. Naturally, this decree caused excitement among the liberated Greeks.

The Romans had an ulterior motive in giving the Greeks their independence. The Greeks would not be free at all. Instead, Rome intended Greece to be a client state of Rome and serve three functions: (1) become a post for Roman surveillance of the East, (2) serve as a buffer state, and (3) act as a main road for any future Roman operations in the east.

During this period, anarchy began to emerge among the confederated city-states in the Achaean League. Many of the cities had been forced to join the League against their will and strived to regain independent status. Their efforts, in turn, led to internal strife within the League, and Rome was called in to pacify the situation.

The Achaean League also was facing internal division with respect to whether the League wanted Rome’s intervention in its affairs. The controlling powers in the Confederacy supported Roman policies, while their rivals argued that the League should be able to operate independently of any intervention of Rome. Naturally, Rome agreed with the controlling powers, and, as a result, the dissenters sought an alliance with Macedon.

Macedon was by no means neutralized as a result of Philip’s defeat in the Second Macedonian War. When Philip died in 179, his son Perseus inherited an army of 40,000 men. Perseus, like his father, harbored a disdain for Rome, and soon after he assumed power he began making contacts with those in Greece who shared his anti-Roman sentiments. Rome, however, was kept aware of this growing Macedonian threat through its espionage efforts and with the help of King Eumenes II of Pergamum. In 197, Eumenes II had succeeded Attalus I as king of Pergamum. In 171, Rome forced Macedon into the Third Macedonian War. In 168, Perseus met defeat at Pydna, and the war officially ended the following year.

Rome now set out to punish certain Greek factions such as the Rhodians, Epireans and Achaeans for their perfidy in supporting Macedon. After seizing territory from Rhodes and devastating Epirus, Rome turned its attention to Achaea. Rome deported to Italy 1000 Achaean men who were reported to have been part of the anti-Roman faction. Among them was the famous historian Polybius. The Romans learned about these men from Callicrates, a traitor to their cause. For seventeen years, these men were held as hostages, thus assuring Greek compliance with Roman policies.

The Achaean League would later fall under the rule of a factional government that was completely dependent on Rome for the maintenance of its power. However, this government would end in the aftermath of the conflict between the Achaean cities of Sparta and Corinth. In 146, an insignificant territorial dispute resulted in Corinth attacking Sparta. Following the attack, a delegation from Sparta traveled to Rome to ask for Roman intervention in this conflict within the Achaean League. As a result, a Roman delegation went to Achaea and demanded that the Achaean League release control of Sparta, Corinth, Argos and some other members of the League. At this point, the League’s leadership consisted of nothing more than unsupported demagogues. They refused to comply with the demand and encouraged an open revolt in order to attain independence from Roman policy. However, this ragtag group was no match for the disciplined Roman legions, and the rebellion quickly faltered. In 146, Rome exacted revenge by the sacking of the City of Corinth and selling its inhabitants into slavery. Rome declared that Achaia was to no longer enjoy independence, but would become a Roman province with Roman rulers.

In Federalist 18, Madison warns that anarchy is a common occurrence in confederations. As he makes clear with the example of the Achaean League, if the United States were to remain a simple confederation, it could meet with disaster. Instead, Madison argues that a unified government acting under a constitution would be the most stable governmental structure for the new nation.

The Risk of Foreign Influence: Roman Alliances

They who well consider the history of similar divisions and confederacies, will find abundant reason to apprehend, that those in contemplation would in no other sense be neighbors than as they would be borderers; that they would neither love nor trust one another, but on the contrary would be a prey to discord, jealousy and mutual injuries; in short, that they would place us exactly in the situations in which some nations doubtless wish to see us, viz., formidable only to each other.

Nay, it is far more probable that in America, as in Europe, neighboring nations, acting under the impulse of opposite interests and unfriendly passions, would frequently be found taking different sides. Considering our distance from Europe, it would be more natural for these confederacies to apprehend danger from one another than from distant nations, and therefore that each of them should be more desirous to guard against the others by the aid of foreign alliances, than to guard against foreign dangers by alliances between themselves. And here let us not forget how much more easy it is to receive foreign fleets in our ports, and foreign armies in our country, than it is to persuade or compel them to depart. How many conquests did the Romans and others make in the characters of allies, and what innovations did they under the same character introduce into the governments of those whom they pretended to protect. – John Jay, Federalist No. 519

In this paper, John Jay rejects the proposal that the states should divide into three or four regional confederacies that enter into alliances with one another. According to Jay, the natural differences in the northern and southern economies and uneven strengths of the states could lead to jealousies between the confederacies. Conflicts among these confederacies could lead an individual confederacy to increase its might by forging alliances with foreign nations. Jay then argues that a foreign ally can manipulate an alliance to conquer a confederacy. As one example, he notes that ancient Rome would act as a friend to a confederacy and slowly take it over.

In Federalist No. 18, James Madison illustrates Jay’s point with his account of the Macedonian Wars and the fall of the Achaean confederacy of Greek city-states.20 Rome initially served as a protector and defender of the Achaean League, ostensibly to keep it stable and independent. However, Rome had its own self interest at heart and, in 146, declared the region to be a Roman province under Roman rule.

In Federalist No. 5, John Jay warns his readers that establishing several interrelated confederations of states would open the door to internal controversies and perhaps even foreign usurpation. This foreign usurpation, Jay suggests, could happen in a way similar to the way that Rome gained dominance over allies like the Achaean League. A foreign nation could join with a confederacy under the guise of friendship, but then, slowly make changes to the confederacy and finally gain power over its former ally.

The Need for a Single Executive

Overview

At the Constitutional Convention, Edmund Randolph of Virginia proposed a three member executive and declared that the single executive would be “the foetus of monarchy.”21 In elaborating on his opposition, Randolph offered four arguments:

1. that the permanent temper of the people was adverse to the very semblance of Monarchy. 2. That a unity was unnecessary a plurality being equally competent to all the objects of the department. 3. That the necessary confidence would never be reposed in a single Magistrate. 4. That the appointments would generally be in favor of some inhabitant near the center of the Community, and consequently the remote parts would not be on an equal footing.22

In Federalist No. 70, Alexander Hamilton points to classical Rome to argue that having multiple executives can lead to destructive rivalries among the officials and even increase the risk of tyranny. To illustrate, he employs the examples of the consuls and military tribunes and the decemvirs.

A Multiple Executive Risks Destructive Rivalries: Consuls and Military Tribunes

Energy in the executive is a leading character in the definition of good government. It is essential to the protection of the community against foreign attacks; It is not less essential to the steady administration of the laws, to the protection of property against those irregular and high handed combinations which sometimes interrupt the ordinary course of justice, to the security of liberty against the enterprises and assaults of ambition, of faction and of anarchy. Every man the least conversant in Roman history knows how often that republic was obliged to take refuge in the absolute power of a single man, under the formidable title of dictator, as well against the intrigues of ambitious individuals, who aspired to the tyranny, and the seditions of whole classes of the community, whose conduct threatened the existence of all government, as against the invasions of external enemies, who menaced the conquest and destruction of Rome.

That unity is conducive to energy will not be disputed. Decision, activity, secrecy, and dispatch will generally characterize the proceedings of one man, in a much more eminent degree, than the proceedings of any greater number; and in proportion as the number is increased, these qualities will be diminished.

This unity may be destroyed in two ways; either by vesting the power in two or more magistrates of equal dignity and authority; or by vesting it ostensibly in one man, subject in whole or in part to the controul and cooperation of others, in the capacity of counselors to him. Of the first, the two consuls of Rome may serve as an example; of the last, we shall find examples in the constitutions of several of the states. New York and New-Jersey, if I recollect right, are the only states, which have intrusted the executive authority wholly to single men. Both these methods of destroying the unity of the executive have their partisans; but the votaries of an executive council are the most numerous. They are both liable, if not to equal, to similar objections; and may in most lights be examined in conjunction.

The experience of other nations will afford little instruction in this head. As far however as it teaches any thing, it teaches us not to be inamoured of plurality in the executive. . . . The Roman history records many instances of mischiefs to the republic from the dissensions between the consuls, and between the military tribunes, who were at times substituted for the consuls. But it gives us no specimens of any peculiar advantages derived to the state,from the circumstance of the plurality of those magistrates. That the dissentions between them were not more frequent, or more fatal, is a matter of astonishment; until we advert to the singular position in which the republic was almost continually placed and to the prudent policy pointed out by the circumstances of the states, and pursued by the consuls, of making a division of the government between them. The Patricians engaged in a perpetual struggle with the Plebeians for the preservation of their antient authorities and dignities; the consuls, who were generally chosen out of the former body, were commonly united by the personal interest they had in the defense of the privileges of their order. In addition to this motive of union, after the arms of the republic had considerably expanded the bounds of its empire, it became an established custom with the consuls to divide the administration between themselves by lot;one of them remaining at Rome to govern the city and its environs; the other taking command in the more distant provinces. This expedient must no doubt have had great influence in preventing those collisions and rivalships, which might otherwise have embroiled the peace of the republic. – Alexander Hamilton, Federalist No. 7023

Here, Alexander Hamilton stresses the importance of having an energetic executive and further argues that the ideal executive should consist of a single officer. Hamilton supports his position, in part, by looking to lessons from classical Rome.24 For Hamilton, this history demonstrates that having multiple executives leads to destructive disunity. However, for the most part, the historical record demonstrates that having multiple executives was not problematic to the stability of the republic. Yet, during the nearly five centuries of the republic, conflicts between consuls caused serious problems.

In 509 B.C.E., with the fall of the monarchy, Rome instituted a new republican government that included two chief magistrates, known as consuls. Originally, the consulship was filled only by men of patrician ancestry, that is, descendants of the original senatorial families of the previous regal regime. However, as Hamilton failed to note, in 367, one of the two consular positions was opened to the Roman plebeian class.

The Roman consuls were annually elected by the patrician-dominated comitia centuriata, After completing one year of service, an ex-consul could seek election again only after a ten-year interval. In the republic, the consuls held imperium, meaning that they would possess both military and civil power. However, any legislation proposed by the consul was subject to the approval of another assembly, the Tribunes of the Plebeians, who could veto any proposals. Further, the consuls would listen to advice given to them by the Senate. Any judicial decree of a consul was subject to appeal to the people if the decree ordered capital punishment. Further, any action taken by one consul was subject to the veto of the co-consul. This dual executive thus had an internal check, that prevented any one consul from becoming a tyrant. When a military campaign began, one or even both consuls commonly left Rome and commanded the army. Of course, this tradition carried a risk, because one or both consuls could die in battle, leaving Rome without one or both executives.

As one might expect, the two consuls sometimes did not agree on an issue. Although the mutual agreement of the consuls served as a critical check on consular power, disagreement between the consuls occasionally did not prevent one consul from pursuing his desired course. For example, in 59, both Gaius Julius Caesar and Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus were co-consuls; however, the conservative Bibulus often opposed Caesar’s proposals. As a result, Gnaeus Pompeius (Pompey the Great), Marcus Licinius Crassus and Caesar, the members of the political alliance known as the Triumvirate, employed their loyal military veterans to harass Bibulus whenever he left his house. Accordingly, Bibulus confined himself to his home, allowing Caesar to run the state without opposition from his co-consul, illegally passing any proposals he wished.

When Rome faced a particularly menacing threat, the government occasionally would resort to a single ruler, known as a dictator, who would be charged with quelling the threat. The dictatorship usually was to last no longer than six months or no longer than needed to complete the dictator’s primary task. A dictator was appointed by the two consuls with the consent of the Senate. Unlike a consul, however, a dictator did not exercise control over military matters. Instead, the dictator would appoint a master of the cavalry, to look after military affairs. With respect to political decision making, a dictator enjoyed greater power than a consul; the tribune of the Plebeians had no veto power against the acts of a dictator.

Although historical records are unclear, the first dictator is believed to have been appointed around the year 500. The Romans frequently resorted to dictators in the fifth century, but less often in the fourth century. For instance, when the Vosci, a neighboring tribe, invaded Roman territory in 407, Publius Cornelius was appointed to eliminate the threat. In the third century, the use of dictators had all but died out except for during brief periods during the Punic Wars. The dictatorship fell into disuse as Roman affairs became more stable at home. However, in the first century, the dictatorship would be revived.

Following years of civil war, in 82, former consul Lucius Cornelius Sulla defeated military forces that had supported the deceased Roman general Marius. That very same year, with the ambitious opposition eliminated and with the support of his army, Sulla had himself appointed dictator. However, Sulla created a new type of dictatorship. Employing military threats, Sulla pressured the Senate into appointing him dictator for life. He ruled absolutely until he voluntarily retired in 79.

Like Sulla, Gaius Julius Caesar was able to gain the dictatorship and hold it longer than the traditional six-month period. In 49, after Caesar illegally crossed the Rubicon River and entered Italy with his army, Rome was once again thrown into civil war. This civil war matched the forces of Caesar against those of his former friend, Pompey the Great who had recently become sole consul. In 48, Caesar defeated Pompey in battle at Pharsalus in Thessaly. Following this victory, and the subsequent assassination of Pompey in Egypt, Caesar was free to rule Italy unopposed. In 46, Caesar made himself dictator for ten years and, in 44, made himself dictator for life.

In Federalist No. 10, Hamilton neglects to mention that dictators such as Caesar and Sulla were not simply checking the ambitious behavior of fellow Roman demagogues, but were pursuing their own ambitious goal of seizing power. Thus, the people of Rome did not seek refuge behind these dictators. Rather, the dictators forced themselves upon Rome.

Another powerful magistracy in Rome was the military tribune. In frenzied times, when conflict was taking place on multiple fronts, two consuls could not to meet the demands of the situation. In these periods, the patrician-dominated assembly, called the comitia centuriata, would elect from the military chiefs a board of men, military tribunes, who would hold. By 366, however, Rome had ceased to use these military tribunes.

When military tribunes failed to back each other, the results could be disastrous. In 402, for example, Rome was at war with several tribes from neighboring territories. In a coordinated attack, the Veii, Capanetes and the Falisci all attacked a Roman fortification under the command of the military tribune Manius Sergius. The situation was desperate for Sergius, and his only hope was support from the main army group, which was camped to his rear. The main army group, however, was commanded by a fellow military tribune named Lucius Verginius. Unfortunately for Sergius’ soldiers, Verginius and Sergius shared a mutual enmity for one another. As a result, Verginius would do nothing until Sergius asked him for his help. Further, Sergius, was too proud to ask his political enemy for assistance. Sergius’ troops suffered massive losses, and the survivors were forced to flee the fort and return to Rome in defeat.

In Federalist No. 70, Alexander Hamilton argues that in order to achieve maximum efficiency in the American executive, no more than one person should serve as the chief executive officer. Hamilton points to the executive rivalries that occurred in Rome in instances such as the conflict between Sergius and Verginius. However, Rome’s difficulties require some perspective. The republic survived for almost five-hundred years. Practically every year saw the election of a new college of chief magistrates in one form or another, be it military tribune or consul. Yet, the instances of internal consular or tribunal dissent were relatively rare.

A Multiple Executive Increases the Risk of Tyranny: The Decemvirs

When power therefore, is placed in the hands of so small a number of men, as to admit of their interests and views being easily combined into a common enterprise, by an artful leader, it becomes more liable to abuse and more dangerous when abused, than if it be lodged in the hands of one man; who from the very circumstance of his being alone, will be more narrowly watched and more readily suspected, and who cannot unite so great a mass of influence as when he is associated with others. The Decemvirs of Rome, whose name denotes their number, were more to be dreaded in their usurpation than any ONE of them could have been. – Alexander Hamilton, Federalist No. 7025

In Federalist No. 70, Hamilton argues the risk of tyranny is greater with a multiple executive than with a single executive officer. In order to prove his point, Hamilton directs his readers to the decemvirs, a group of rulers who despotically dominated Rome in the mid-fifth century B.C.E.26

The Roman republic witnessed a continuing power struggle between the patricians, the wealthy ruling class who enjoyed complete control, and the plebeians, the commoners who comprised the majority of the city of Rome. One of the major sources of tension between the two social classes in ancient Rome was the judicial system, which employed a system of common law. As common law, the laws were not codified, and the patrician magistrates exercised complete discretion in judicial matters.

In 462, Gaius Terentilius Harsa, a Tribune of the Plebeians, challenged this discretionary authority. Harsa insisted that the laws of Rome be codified. With codification, the magistrates would know what the law was and presumably would apply it even-handedly to both patricians and plebeians. Initially, this proposal did not garner support from the patricians. However, after a group of commoners stormed and seized the Capitol, they submitted to the plebian demand.

The patricians first sent a group of commissioners to Greece to observe the methods used to codify laws in the East. After this research was complete, Rome interrupted its normal magistracy elections and instead appointed the college of decemvirs, ten men to rule the state, and to draft the laws over the period of one year. Each of the ten men had ultimate power over the state, and rotated their command on a daily basis. Further, each man was assigned twelve lictors, the traditional guards and agents of the Roman consuls who carried fasces, long axes bundled with rods, which were the traditional symbol of royalty in ancient Rome.

In March, 451, the first college of the decemvirs assumed power and set to work drafting the law as well as administering to the needs of the state. At the end of their year in power, the decemvirs had completed ten tables of laws, written on large flat sheets of wood. However, the task of codifying the laws was incomplete, and so a second college of decemvirs was authorized to finish the task over the next year.

In May, 450, the second college of decemvirs began its work under the leadership of Appius Claudius, a patrician who served with the first college of decemvirs. During its time in power, the second decemvirate would complete a further two tables of laws, making a total of twelve tables of laws. However, during this second college, the decemvirs began to exercise a tyrannical hold of Rome. In 450, the decemvirs entered the Forum, each surrounded by his twelve lictors. Previously, only the one decemvir who was in charge of the state for the day would be surrounded by his lictors. Naturally, this display served as an overwhelming demonstration of power and served to intimidate those who would normally stand up to their actions.

The decemvirs then allowed the patricians to take advantage of the plebeians without any legal recourse. Young patricians would crowd around the decemvirs as escorts, stealing whatever property they wished from the plebeians and generally mistreating them. The patricians also resorted to violence against the plebeians, scourging some and beheading others.

In May 449, the decemvirs were supposed to relinquish their power. However, they called no elections, and no one was appointed in their places. As a result, the people feared that these men comprised a new and unstoppable dictatorship. Meanwhile, the Sabines and the Aequi, both tribes from the areas surrounding Rome, attacked Roman territory, and the Roman Army was ordered to engage them. However, even when a crisis faced the state from an external source, the decemvirs would not stop their tyrannical ways. While out on campaign against the Sabines, one Roman, Lucius Siccius, held secret meetings with his comrades in which they discussed the possibility of renaming plebeian Tribunes and caused the Roman plebeians to refuse to military service and secede by migrating to the Aventine Hill. News of these meetings found its way to the decemvirs, who then promptly arranged for Siccius’ assassination.

However, the greatest outrage of the decemvirs, and ultimately the source of their downfall, was the attempted enslavement of a plebeian girl named Verginia. Decemvir Appius Claudius had become infatuated with Verginia despite her betrothal to a plebeian. In a scheme to have his way with the girl, Appius created the false charge that Verginia was actually a daughter of a slave, and, moreover that she was born at one of his agent’s estate. If true, Verginia would have been the property of Appius’ agent, who would naturally give Appius access to her. Verginia’s father, Verginius, went to the Forum and appealed to Appius Claudius to drop his false accusation. When Appius refused to listen to his pleas, Verginius grabbed a butcher’s knife and thrust it into Verginia.

Vergenius’ defiance of the decemvirs was well received by the plebeians. Verginius then rushed to the legions, which were still on campaign, and successfully urged them to come to Rome and occupy the Aventine Hill as a demonstration of revolt. Powerless, the decemvirs were forced to relinquish their positions. Shortly thereafter, a new government was elected which was identical to the government preceding the two colleges of decemvirs. Justice was restored; the twelve tables of law would be equally administered to plebeian and patrician alike. Appius Claudius and another decemvir committed suicide after being taken into custody by the new Roman government. The other eight decemvirs would flee Rome forever, and, in 449, the state seized their property.

In Federalist Paper No. 70, Hamilton warns of the dangers of having multiple executives ruling a country. By using the example of the decemvirs, Hamilton argues a that a body of multiple official with common interests can become oppressive. Hamilton asserts that a better system is the single Executive who will be less prone to act on any tyrannical impulses than would be a group of men.

Structuring Government

Overview

In constructing a new governmental system, the Framers had to face such questions as how the new national government would interact with the existing state governments and what sorts of internal checks would prevent tyranny. Although Madison believed that he was moving beyond the political science of the past, he still sought to learn from history.27 In classical Rome, he found assistance in the stories of Rome’s early leaders, in its assemblies with overlapping jurisdictions, in the senate as an internal governmental check, and in the employment of tribunes as a popular check on the patrician senate.

Creating a Constitution by Assembly: Rome’s Early Lawgivers

It is not a little remarkable that in every case reported by antient history, in which government has been established with deliberation and consent, the task of framing it has not been committed to an assembly of men, but has been performed by some individual citizen of preeminent wisdom and approved integrity. . . . The foundation of the original government of Rome was laid by Romulus; and the work completed by two of his elective successors, Numa and Tullius Hostilius. On the abolition of Royalty the Consular administration was substituted by Brutus, who stepped forward with a project for such reform, which he alledged had been prepared by Servius Tullius, and to which his address obtained the assent and ratification of the Senate and the people. History informs us likewise of the difficulties with which these celebrated reformers had to contend; as well as of the expedients which they were obliged to employ, in order to carry their reforms into effect. – James Madison, Federalist No. 3828

In Federalist No. 38, James Madison notes a succession of Roman heroes who enjoy the reputation of single-handedly making drastic improvements in the City of Rome.29 In doing so, he notes that a prevalent theme among the ancient civilizations was that of the lone-ruler singlehandedly building the state. These individual heroes stand in contrast to the large number of delegates from several states who together shaped America’s Constitution. Madison only subtly suggests that a better way to construct a government is to employ a delegation of thoughtful individuals of good will.

The first Roman lawgiver to whom Madison refers is Romulus. According to one legend, Aeneas, the Trojan hero, was blown off course by the Juno and landed in Italy. Aeneas married a member of the powerful Laurentes royal clan and ruled over their territory until he drowned in the brook Numicius. His son, Ascanius, then founded the city of Alba Longa, where Aeneas’ descendants remained as leaders. However, after 300 years had passed, Numitor and Amulius, both brothers and members of Aeneas’ royal lineage, became rivals, and the evil Amulius ousted Numitor from the throne. Amulius then learned that his niece, Rhea Silva, had given birth to twins who were fathered by the God Mars.

Upon realizing that the twins, Romulus and Remus, stood to inherit the throne of Alba Amulius ordered them thrown in the Tiber River. With Romulus and Remus out of the way, Amulius was then secure in his rule. However, the two infants did not perish, but instead floated downstream and landed on the riverbank. There, they were rescued and fed by a she-wolf. Following their rescue, Romulus and Remus were discovered by Faustulus, a shepherd, who took in the two boys and raised them. When they were old enough, Romulus and Remus returned to Alba and exacted revenge on their great uncle by killing him. Leaving their grandfather to run Alba, they then set out on their own to found a new city.

When the twins arrived at the site where the shepherd had raised them, Remus saw six vultures, which he took as a sign that he would rule the new city. However, Romulus later saw vultures as well, but double in number. Romulus interpreted the greater number to mean that he was to rule the new city. Each brother was proclaimed king by his respective followers, and Romulus and Remus each selected one of the nearby seven hills on which to start his kingdom. However, according to one legend, Romulus would later kill his brother Remus after Remus tauntingly jumped over the wall of Romulus’ fledgling fortifications. After the murder of Remus, Romulus remarked, “so shall perish all who attempt to pass over our walls,” and, after 753 B.C., he was ruler of the city.

This city on the Tiber River would later be named Rome to honor its founder, Romulus. While king, Romulus took many steps to ensure the stability of the city. To build up the population, he declared the areas of the Palatine and Capitoline Hills to be places of refuge, which attracted diverse settlers from the surrounding regions. In order to maintain the population, he needed an influx of women to mate with his predominantly male subject. As a solution, Romulus arranged to have a festival honoring the God Consus with a neighboring tribe called the Sabines. After the Sabines were too intoxicated to resist, the men of Rome grabbed the Sabine women and carried them back to the fortified city of Rome. This incident became known as the rape of the Sabines.

Naturally, conflict opened up between the Romans and the Sabines, but, when Rome was on the verge of defeat, Romulus prayed to the God Jupiter and promised to construct a temple in his honor if he would deliver the Romans from peril. Jupiter answered the prayer and the Romans were able to turn the tide of the battle. It was at this point that the Sabine women, who had been captured by the Romans, intervened on the battlefield and were able to make a peace between the men. After this, Romulus and the Sabine king, Titus Tatius, would co-rule Rome in harmony. Thus, Romulus’ plan to ensure the growth of the Roman population was a success. Rome now had an influx of much needed women, and Rome achieved peace with the neighboring Sabine tribe.

Romulus ruled over Rome for a total of thirty-seven years. During his long rule, Romulus is credited with creating Rome’s governmental structures. To assist in ruling the state, he chose one hundred people and assigned them positions in the senate. These early Senators were known as patres. Their descendants would also achieve positions of power in Rome as the hereditary ruling class known as the patricii (patricians). Further, he permitted the commoners to create an assembly and gave it a code of law. In 716, Romulus mysteriously disappeared, leaving the city of Rome without a ruler.

Following a year without a king, Numa Pompilius assumed control of Rome. Of Sabine descent and of a highly religious nature, he established Rome’s religious foundation. Because he saw how destructive military life was to morality, he endorsed a peaceful way of life. To this end he commissioned the construction of the Temple of Janus. The doors on this temple were to be closed whenever Rome was at peace. The doors remained closed for Pompilius’ entire reign. However, as an indicator of Roman military policy and the rareness of peace, the gates of Janus were shut for only two short periods afterwards, once after Manlius’ consulship at the end of the First Punic war in 241and once again during the reign of Caesar Augustus in 29.

In his creation of Rome’s religion, Pompilius set up a religious hierarchy of priests. He established priest positions (flamines) to honor Jupiter, Mars and Quirinus., and the pontifex maximus, the position of high priest. Through the efforts of Pompilius, the Alban cult of Vesta was transferred to Rome. Pompilius also developed the Roman calendar.

After Pompilius’ death in 673, the Senate ratified the choice of Tullus Hostilius as the new king. Hostilius, a warlike leader, stood in stark contrast to Pompilius and his peaceful ways. Hostilius would bring power to Rome by subjecting the tribes surrounding the city to war and defeat. However, Hostilius also was committed to construction projects, such as his construction of the Curia Hostilia, built as the Senate House at the base of the Capitoline Hill.

In 641, following the disappearance of Tullus Hostilius, Ancus Marcius reigned over Rome. With Marcius’ death came an end the line of kings from the Sabine tribe. In their place, the Senate elected the first in a line of three kings of Etruscan origin, Tarquinius Priscus. In 578, the sons of Ancus Marcius assassinated Tarquinius Priscus. In the wake of the murder, Priscus’ wife, Tanaquil installed their adopted son, Servius Tullius as the king of Rome.

Servius Tullius enjoys the reputation as one of the most important statesmen in Roman history. During his rule, he took considerable measures to improve the infrastructure of Rome. Among his most important accomplishments was the division of the classes in Rome. Tullius established five classes, each divided into centuries, and created the comitia centuriata, which made various political decisions.

Tullius also extended the physical borders of Rome by expanding the city to the Viminal and Quirinal Hills. He then constructed a wall that surrounded all seven hills of Rome. He thus marked the boundary of Rome as it would stand throughout the republican era.

As with many rulers of Rome, Servius Tullius’ life was cut short by murder. Tullius’ daughter, Tullia, had married an equally ambitious man named Lucius Tarquinius. Upon learning that Servius Tullius intended to hand the power of Rome over to the Senate, Lucius fell upon Tullius and threw him down a flight of stairs. Afterward, Tullia, Tullius’ own daughter, ran him over with a chariot. Despite the boldness of these acts, the Senate acquiesced to the argument that this was a legitimate usurpation and not murder. As a result, Lucius Tarquinius became the ruler of Rome.

The Tarquin line of kings would end after the acts by Lucius’ son Sextus Tarquinius caused a revolution. After he raped the wife of a wealthy patrician, a group of patricians staged a revolt in order to gain liberty from the king and his family. In the wake of the revolt led by Junius Brutus in 509, the Tarquin royal family was exiled from Rome. The expulsion of the king marked the end of Roman monarchies and the beginning of the republican period.

The Senate created the position of consul to lead the governing of the state and Lucius Junius Brutus and Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus became the first consuls. Brutus set out a new model of government, which was said to be the model designed by former king Servius Tullius. Brutus and Collatinus returned the Senate to its original number; it had been drastically reduced by Lucius Tarquinius. The two consuls also helped the plebeians by re-establishing many of the rights that Lucius Tarquinius had revoked. The plebeians were allowed to have their own judges and the right to appeal to their own respective tribes. In a show of dramatic devotion to the newly emerging republic, Brutus ordered the execution of two of his own sons when he learned that they were participating in a plot to restore Lucius Tarquinius to power. Brutus’ consulship ended when he died in battle resisting an army raised by the Tarquin royal family.

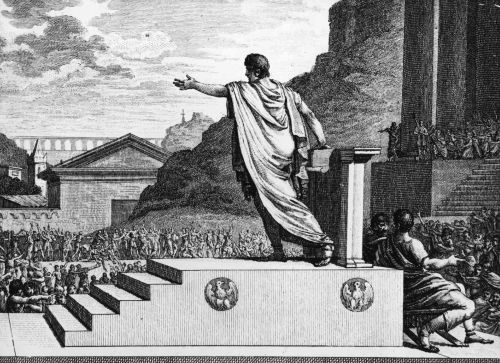

Interestingly, it was not Brutus who was responsible for the ban on royalty in Rome. Rather it was a consul, named Publius Valerius, who pronounced that there would be no more kings ruling Rome. As an honor, the people called Valerius “Publicola,” meaning “peoplelover,” because of his work in founding the republican government. The authors of The Federalist chose his name, “Publius.” as the pen name with which they would sign their contributions to the debate over ratification.

In Federalist No. 38, Madison notes how the foundations of Roman government were laid by individuals acting single-handedly. This method is in contrast to the method that the United States adopted in drafting its Constitution. Madison argues it is safer in the planning of a new government to use a number of framers, as opposed to one man. One man, he argues, can be easily corrupted and infringe upon the liberties of the people. Thus, a group, like the gathering in Philadelphia in 1787, is the safest way to create a government and protect the liberties of the citizens.

Multiple Legislatures: The Comitia Centuriata and the Comitia Tributa

I flatter myself it has been clearly shewn in my last number, that the particular States, under the proposed Constitution, would have COEQUAL authority with the Union in the article of revenue, except as to duties on imports.

It is well known, that in the Roman Republic the Legislative authority in the last resort, resided for ages in two different political bodies; not as branches of the same Legislature, but as distinct and independent Legislatures, in each of which an opposite interest prevailed; in one, the Patrician–in the other, the Plebeian. Many arguments have been made adduced to prove the unfitness of two such seemingly contradictory authorities, each having power to annul or repeal the acts of the other. But a man would have been regarded as frantic who should have In the case particularly under consideration, there is no such contradiction as appears in the example cited; there is no power on either side to annul the acts of the other. And in practice there is little reason to apprehend any inconvenience; because, in a short course of time, the wants of the States will naturally reduce themselves within a very narrow compass; and in the interim, the United States will in all probability, find it convenient to abstain wholly from those objects to which the particular States would be inclined to resort. – attempted at Rome, to disprove their existence. It will already be understood that I allude to the COMITIA CENTURIATA, and COMITIA TRIBUTA. The former, in which the people voted by Centuries, was so arranged as to give a superiority to the Patrician interest: in the latter, in which numbers prevailed, the Plebeian interest had an entire predominancy. And yet the two Legislatures coexisted for ages, and the Roman Republic attained to the pinnacle of human greatness.

In the case particularly under consideration, there is no such contradiction as appears in the example cited; there is no power on either side to annul the acts of the other. And in practice there is little reason to apprehend any inconvenience; because, in a short course of time, the wants of the States will naturally reduce themselves within a very narrow compass; and in the interim, the United States will in all probability, find it convenient to abstain wholly from those objects to which the particular States would be inclined to resort. – Alexander Hamilton, Federalist No. 3430

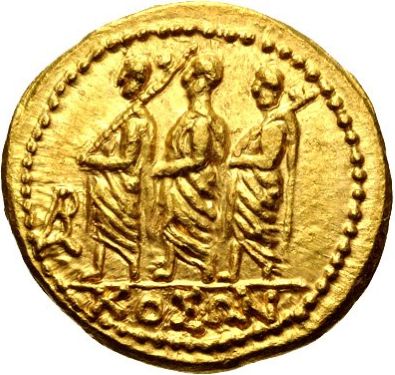

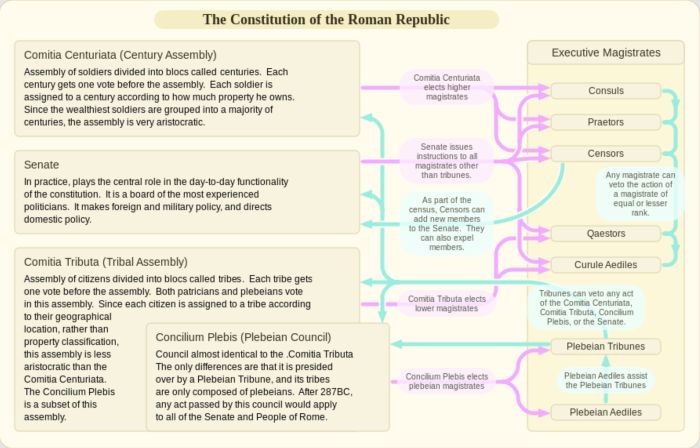

In this paper, Alexander Hamilton argues in favor of permitting both the individual states and the federal government to impose taxes. In order to counter any criticism that there would be conflicts between these dual systems, Hamilton draws an analogy to the legislative assemblies of classical Rome and their overlapping jurisdictions.31 In the republican era, the Roman institutions of the comitia centuriata and the comitia tributa had similar responsibilities and powers; however, their interests were biased towards different classes of society, and they followed different operating procedures.

According to legend, after Servius Tullius assumed the throne in 578 B.C.E., he made many improvements to the Roman infrastructure, including establishing the comitia centuriata. Previously, there had been only the comitia curiata, which was based on a clan system, in which the Roman populous was divided into three tribes and then subdivided into ten groups (curiae) per tribe. Under the earlier system, members of the comitia curiae could vote on such matters as declaring war and appointing priests to various religious positions.

Underlying the creation of the comitia centuriata was a new system of political organization. The government took a census of every free person within Roman territory and recorded his or her wealth. The people were then organized into one of 5 classes, which were divided into a total of 193 centuries. The first class encompassed the wealthiest portions of Roman society, including 80 centuries of wealthy citizens and 18 centuries of the knightly class, known as equestrians. The classes were arranged such that the wealthiest Romans fell into the first class and the members were progressively poorer from class one to class five. When it came time to vote on an issue, the voting started with the first class and then proceeded onto the second class and so forth until a majority was reached. However, because 98 of the 193 centuries were in the first class, there was usually a majority as soon as the first class voted. Thus, the political power in Rome remained firmly in the hands of the patricians, who comprised the first voting class.

Although the comitia centuriata did lose some of its importance as time passed, the comitia nonetheless retained many of its duties throughout the republican era. The comitia centuriata remained responsible for selecting military leaders, censors, consuls, and other senior magistrates. However, because its size made it cumbersome, the comitia centuriata, it was rarely convened to make decisions on the day-to-day operations of the republic. Instead, the much smaller and therefore more practical Senate oversaw the general matters of the state.

In stark contrast to the patrician-dominated comitia centuriata was the comitia tributa (tribal assembly). This assembly was organized in 312 by Appius Claudius and was based on a tribal system similar to that of the comitia curiata. The assembly consisted of thirty-five tribes, with each Roman citizen assigned to one of the tribes.

When voting on an issue, the comitia tributa favored the masses of Roman plebeians while the comitia centuriata favored the patrician class. The strong plebeian control of the comitia tributa stemmed from the equality in the voting scheme of the assembly. Instead of reserving the majority of voting units for patricians, it provided a system for representing Roman society in proportion to Rome’s actual class composition. Thus, the small number of patricians was dwarfed by the significantly larger number of free Romans plebeians. A tribe’s vote was simply determined by counting the number of people from that tribe in attendance on the day of the vote. Because the plebeians could muster a much larger number of votes than the patricians, they held sway. However, the patricians exercised a check on this system. As with the comitia centuriata, the comitia tributa could vote on only those legislative proposals that the Senate had promulgated.

The duties of the comitia tributa were of less significance than those of the comitia centuriata. It would elect minor magistrates such as tribunes, aediles and quaestors. However, by 287, both the comitia centuriata and the comitia tributa had the power to legislate. Further, because of the relative ease of holding a vote in the comitia tributa, consuls would increasingly take their legislative proposals to that assembly in order to avoid convening the larger and more complex comitia centuriata. Therefore, it became increasingly more common for legislation, called plebiscites, to come from the comitia tributa.

In Federalist No. 34, Hamilton argues that governmental bodies with overlapping duties can exist contemporaneously. In classical Rome, there were two such legislative assemblies with overlapping duties. The long life of the republic indicates that establishing redundant legislatures will not necessarily cripple the state. Hamilton extends this argument, to declare that the United States can have a dual system of taxation, with both individual States and the federal government possessing the power to levy taxes to suit their needs. However, Hamilton writes as an advocate and does not discuss differences between the Roman and proposed American systems, in particular, the domination of the Roman Senate over both assemblies and Rome’s unitary government as opposed to the dual federal-state governmental system in the United States. Such an analysis would require addressing many questions about whether these differences make the historical analogy apposite, a task perhaps not appropriate for a newspaper column.

The Senate as an Internal Governmental Check

It adds no small weight to all these considerations, to recollect, that history informs us of no longlived republic which had not a senate. Sparta, Rome and Carthage are in fact the only states to whom that character can be applied. . . .These examples, though unfit for the imitation, as they are repugnant to the genius of America, are notwithstanding, when compared to the fugitive and turbulent existence of other antient republics, very instructive proofs of the necessity of some institution that will blend stability with liberty. . . . The people can never wilfully betray their own interests: but they may possibly be betrayed by the representatives of the people; and the danger will be evidently greater where the whole legislative trust is lodged in the hands of one body of men than where the concurrence of separate and dissimilar bodies is required in every public act. – James Madison, Federalist No. 6332

In Federalist No. 63, James Madison stresses the importance of a senatorial body in the proposed national government and supports his position with examples from Carthage, Rome and Sparta. With these examples, Madison argues that an important part of a long-lived republic is a senate that serves in conjunction with the lower legislative body and the executive in a system of checks and balances.33

The foundations of the Roman senate date back to the time of Romulus, the founder of ancient Rome. In 753 B.C.E., Romulus, established a council of elders that became known as the senate. This body of one hundred men served as his advisory council. Romulus elevated the members of the senate to the status of patres (fathers of Roman society). As a result, their descendants would inherit the privileged noble status of patricii (patricians).

With the fall of the Roman monarchy in 509, the senate took on new duties. Now composed of 300 men, the senate served as an advisory board and convened when summoned by one of the two consuls or a praetor, the magistrate responsible for the administration of justice and sometimes the governor of a Roman province. In addition to its advisory role, the senate exercised control over public finances and oversaw public works projects. It also had a major voice in foreign policy and oversaw the administration of the ever-growing number of Roman provinces.