Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Achaemenid architecture includes all architectural achievements of the Achaemenid Persians manifesting in construction of spectacular cities used for governance and inhabitation (Persepolis, Susa, Ecbatana), temples made for worship and social gatherings (such as Zoroastrian temples), and mausoleums erected in honor of fallen kings (such as the burial tomb of Cyrus the Great). The quintessential feature of Persian architecture was its eclectic nature with elements of Assyrian, Egyptian, Median and Asiatic Greek all incorporated, yet producing a unique Persian identity seen in the finished product.[1] Achaemenid architecture is academically classified under Persian architecture in terms of its style and design.[2]

Achaemenid architectural heritage, beginning with the expansion of the empire around 550 B.C.E., was a period of artistic growth that left an extraordinary architectural legacy ranging from Cyrus the Great’s solemn tomb in Pasargadae to the splendid structures of the opulent city of Persepolis.[3] With the advent of the second Persian Empire, the Sassanid dynasty (224–624 C.E.), revived Achaemenid tradition by construction of temples dedicated to fire, and monumental palaces.[3]

Perhaps the most striking extant structures to date are the ruins of Persepolis, a once opulent city established by the Achaemenid king, Darius the Great for governmental and ceremonial functions, and also acting as one of the empire’s four capitals. Persepolis, would take 100 years to complete and would finally be ransacked and burnt by the troops of Alexander the Great in 330 B.C.E.[4] Similar architectural infrastructures were also erected at Susa and Ecbatana by Darius the Great, serving similar functions as Persepolis, such as reception of foreign dignitaries and delegates, performance of imperial ceremonies and duties, and also housing the kings.

Mausoleum of Cyrus the Great – Pasargadae

Overview

Despite having ruled over much of the ancient world, Cyrus the Great would design a tomb that depicts extreme simplicity and modesty when compared to those of other ancient kings and rulers. The simplicity of the structure has a powerful effect on the viewer, since aside from a few cyma moldings below the roof and a small rosette above its small entrance, there are no other stylistic distractions.[5]

Structural Details

After his death, Cyrus the Great’s remains were interred in his capital city of Pasargadae, where today his limestone tomb (built around 540–530 B.C.E.[6]) still exists. The translated ancient accounts give a vivid description of the tomb both geometrically and aesthetically; The tomb’s geometric shape has changed little over the years, still maintaining a large stone of quadrangular form at the base (forty five feet by forty two feet[7]), followed by a pyramidal succession of seven, irregular smaller rectangular stones (possibly as a reference to the seven planets[7] of the solar system) reaching a height of eighteen feet, until the structure is curtailed by a rectangularly formed cubical edifice with a small opening or window on the side, where the slenderest man can barely squeeze through.[8] The roof of the edifice and indeed the structure, is an elongated limestone pediment.[7]

The edifice, or the “small house” is a rectangular, elongated cube that lies directly on top of the pyramidal stone steps, and is six and a half feet (2.0 m) in width, six and a half feet (2.0 m) in height, and 10 ft (3.0 m) in length.[9] The inside of the edifice is occupied by a small chamber a few feet in width and height, and around ten feet deep. It was inside this chamber where the bed and coffin of Cyrus the Great would have been situated.[7] The edifice has a pediment roof possessing the same length and width dimensions as the edifice itself. Around the tomb were a series of columns, the original structure which they supported is no longer present.[7] Arrian’s direct testimony indicates that Cyrus the Great was indeed buried in the chamber inside the edifice, as he describes Alexander seeing it during his visit to Pasargadae, but it is also a possibility that the body of Cyrus the Great had been interred below the structure, and that the tomb seen on the top is in fact a cenotaph or a false tomb.

There was originally a golden coffin inside the mausoleum, resting on a table with golden supports, inside of which the body of Cyrus the Great was interred. Upon his resting place, was a covering of tapestry and drapes made from the best available Babylonian materials, using fine Median workmanship; below his bed was a fine red carpet, covering the narrow rectangular base of his tomb.[8]

History

Translated Greek accounts describe the tomb as having been placed in the fertile Pasargadae gardens, surrounded by trees and ornamental shrubs, with a group of Achaemenian protectors (the “Magi”), stationed nearby to protect the edifice from theft or damage.[8][10]

The magi were a group of on-site Zoroastrian observers, located in their separate but attached structure possibly a caravanserai, paid and cared for by the Achaemenid state (by some accounts they received a salary of daily bread and flour, and one sheep payment a day[7]). The magi were placed in charge of maintenance and also prevention of theft. Years later, in the ensuing chaos created by Alexander the Great’s invasion of Persia and loss of a centralized authority directing and caring for the Magi, Cyrus the Great’s tomb was broken into and most of its luxuries were looted. When Alexander reached the tomb, he was horrified by the manner in which the tomb was treated, and questioned the Magi and put them to court.[8] On some accounts, Alexander’s decision to put the Magi on trial was more about his attempt to undermine their influence and his show of power in his newly conquered empire, than a concern for Cyrus’s tomb.[11] Regardless, Alexander the Great ordered Aristobulus of Cassandreia to improve the tomb’s condition and restore its interior.[8]

The tomb was originally ornamented with an inscription that, according to Strabo (and other ancient sources), stated:[9]

O man! I am Cyrus the Great, who gave the Persians an empire and was the king of Asia. Grudge me not therefore this monument.

The edifice has survived the test of time for some 2,500 years. After the Arab invasion into Persia and collapse of the Sassanid Empire, Arab armies wanted to destroy this historical artifact, on the basis that it was not in congruence to their Islamic tenets, but quick thinking on the part of the local Persians prevented this disaster. The Persians renamed the tomb, and presented it to the invading army as the tomb of King Solomon’s mother. It is likely that the inscription was lost at this time.[12]

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi (Shah of Iran), the last official monarch of Persia, during his 2,500 year celebration of the Persian Empire paid significant homage to the Achaemenid kings and specially Cyrus the Great. Just as Alexander the Great before him, the Shah of Iran wanted to appeal to Cyrus’s legacy to legitimize his own rule by extension.[13] Shah of Iran however was generally interested in protection of imperial historical artifacts.

After the Iranian revolution, the tomb of Cyrus the Great survived the initial chaos and vandalism propagated by the Islamic revolutionary hardliners who equated Persian imperial historical artifacts with the late Shah of Iran. There are allegations of the tomb being in danger of damage from the construction of the Sivand Dam on river Polvar (located in the province of Pars) and water related damage, but there is no official acknowledgement of this claim. United Nations recognizes the tomb of Cyrus the Great and Pasargadae as a UNESCO World Heritage site.[6]

Scholars agree that it was Darius the Great who initiated the construction and expansion of the Persepolis project, however German archaeologist Ernst E. Herzfeld, believed that it was Cyrus the Great who chose the site for the construction, although it ultimately came down to Darius the Great to finish the construction and create its impressive buildings. Excavations on behalf of the Oriental Institute of The University of Chicago, headed by Herzfeld in 1931 and later cooperation by Eric F. Schmidt in 1933 led to some of the most impressive uncovering of Achaemenid artifacts, palaces, and structures. Herzfeld felt that the site of Persepolis was made for special ceremonies and was meant to convey the power of the Achaemenid empire to its subject nations.[9]

On some accounts, Persepolis was never officially finished as its existence was cut short by Alexander the Great, who in a fit of anger, ordered the burning of the city in 330 B.C.E. Started originally by Darius the Great a century earlier, the structure was constantly changing, receiving upgrades from subsequent Persian monarchs, and undergoing renovation to maintain its impressive façade. After the burning of the city, Persepolis was deserted and it was relatively lost to history until the excavations of Herzfeld, Schmidt, and the Chicago team uncovered it in the 1930s. This great historical artifact is unfortunately at serious risk of “irreparable damage”[3] from neglect, the elements, and vandalism.

Persepolis was by no means the only large scale Achaemenid project, as Susa also hosted a similar structure initiated by Darius for similar ceremonial purposes. However, that history is able to enjoy the remains of Persepolis as opposed to meager remnants of Susa, owes partly to selection of stone in construction of Persepolis over mud-brick in Susa, and the fact that it had been relatively uninhabited, protecting it from wear and tear of inhabitants. Politically, Persepolis also was a significant find because nearby discovery of Naqsh-e Rustam, the Persian necropolis home to Darius the Great shed light on the significance it has had as one of the major capitals of the empire.[5] Naqsh-e Rustam would not only house Darius the Great, but also his son Xerxes the Great, Artaxerxes I, and Darius II as well. The necropolis complex was looted following invasion of Alexander, and possibly in the Sassanid period and during the Arab invasion.

During the time of Shah of Iran, the structure enjoyed protection and coverage as Mohammad Reza Shah appeased to its royal and national symbolism. During this time period many western politicians, poets, artists, and writers were gravitated to Iran, and Persepolis, either as a function of the political relations with the Iranian monarchy or to report on, or visit the ruins. Such figures include the procession of international dignitaries attending the 2,500 year celebration of the Persian Empire held by Shah, as well as individual visits by such figures as Heinrich Lübke of Germany, and Ralph Graves of Life magazine. In an article in “Life“ in 1971, Graves describes his experience at Persepolis in the following way:

When you see Persepolis for the first time as I did, facing Marvdasht, you are likely to be disappointed but once inside the ruins themselves you are overwhelmed by the still-proud soaring columns, and by the quality and the fresh state of the bas-relief carvings which are certainly among the finest in the history of the world’s art. But mostly you are transfixed by the sudden realization that all this happened 24 centuries ago, and that people from every nation in the known world of the time had stood in the same place and felt the same.[14]

Four-Winged Guardian – Pasargadae

Perhaps one of the most memorable remaining architectural and artistic works is the bas-relief of Cyrus the Great in Pasargadae. This is a bas-relief cut upon a stone slab depicting a figure or a guardian man, most likely a resemblance of Cyrus himself, possessing four wings shown in an Assyrian style, dressed in Elamite traditional clothing, assuming a pose and figure of an Egyptian god, and wearing a crown that has two horns, in what resembles an Ovis longipes palaeoaegyptiacus. The structure originally had an upper stone slab that in three different languages, (Old Persian, Elamite, Babylonian) declared, “I, (am) Cyrus the king, an Achaemenid.”[15] This carved in limestone writing was in place when Sir Robert Ker Poter described the piece in 1818 but, at some point has been lost.

David Stronach has suggested that there were originally four such figures, set against doorways to the Palace of Cyrus in Pasargadae.[15] That this bas-relief has such an eclectic styling with elements of Egyptian, Elamite, and Assyrian, reflects “..’the oecumenical attitude of the Achaemenian kings, who from the time of Cyrus, onward adopted a liberal policy of tolerance and conciliation toward the various religions embraced within their empire’…”[15] It would therefore depict the eclectic nature of Achaemenid life from policies of the kings to their choice of architecture.

Herodotus, recounts that Cyrus saw in his sleep the oldest son of Hystaspes, [Darius the Great] with wings upon his shoulders, shadowing with the one wing Asia, and with the other wing Europe.[15] Noted Iranologist, Ilya Gershevitch explains this statement by Herodotus and its connection with the four winged figure in the following way:[15]

Herodotus, therefore as I surmise, may have known of the close connection, between this type of winged figure, and the image of the Iranian majesty, which he associated with a dream prognosticating, the king’s death, before his last, fatal campaign across the Oxus.

This relief sculpture, in a sense depicts the eclectic inclusion of various art forms by the Achaemenids, yet their ability to create a new synthetic form that is uniquely Persian in style, and heavily dependent on the contributions of their subject states. After all, that is what distinguishes Achaemenid architecture from those of other kingdoms. It is its originality in context of fusion and inclusion of existing styles, in such a way as to create awe-inspiring structures.

Persepolis

Overview

Persepolis is the Latinized version of the Old Persian name, “Parsa” literally meaning the “city of Persians.” Another spectacular achievement of the Achaemenids, Persepolis became one of the four capitals of the empire. Initiated by Darius the Great around 518 B.C.E., it would grow to become a center for ceremonial and cultural festivities, a center for dignitaries and visitors to pay homage to the king, a private residence for the Persian kings, a place for satraps to bring gifts for the king in the Spring during the festival of Nowruz, as well as a place of governance and ordinance.[9] Persepolis’s prestige and grand riches were well known in the ancient world, and it was best described by the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus as “the richest city under the sun”.[5]

Structural Details

Today the archaeological remnants of this once opulent city are about 70 kilometers northeast of the modern Iranian city of Shiraz, in the Pars province, in southwestern Iran. Persepolis is a wide, elevated complex 40 feet high, 100 feet wide, and a third of a mile long,[3] composed of multiple halls, corridors, a wide terrace, and a special, double, symmetrical stairway that would provide access to the top of the terrace.[9] The stairway would delineate relief scenes of various motifs of daily life or nature, including some that were literal as well as metaphorical; Some scenes would show natural acts such as a lion attacking its prey but bear symbolism of spring and the Nowruz festival. Other scenes would depict, subjects from all states of the empire presenting gifts to the king, as well as scenes depicting royal guards, or scenes of social interactions between the guards or the dignitaries.[9] This stairway is sometimes referred to as “All countries.”[4]

The structure was constructed from various halls and complexes that included, hall of Apadana (the largest hall with 36 columns), “Tachar” (the private chamber of Darius the Great), “Hadish” (added later on as a private chamber for king Xerxes the Great), the “Talar-i-Takht” also known as the 100-columned hall serving as the throne hall for general meeting with the king, “Darvazeh-i-Mellal” (the gate of all nations), the “khazaneh” (the royal treasury), a hall/palace complex later on developed by Artaxerxes III, Tripylon (council hall), and the “rock cut tombs of the kings” or Naqsh-e Rustam.[9]

The most impressive hall in the complex is the Apadana hall, occupying an area of about 109 square meters with 36 Persian columns, each more than 19 m tall. Each column is fluted, with a square base (except a few in the porticos), and an elaborate capital with two animals supporting the roof. The structure was originally closed off from the elements by mud-brick walls over 5 meters thick and over 20 meters.[16] The columns have a composite capital depicting addorsed bulls or creatures. Those columns in the porticoes not only would possess a circular base, but would also have an ornate capital after the end of the fluting, only to be curtailed by detailed addorsed bulls, supporting the roof.[16]

Apadana’s relief is also unique in that it delineates the presence and power of the king. Known as “Treasure reliefs” the depicted scenes on Apadana stress the continuity of the kingdom through Darius the Great, and stress his presence throughout the empire, as well as depict his army of Persian immortals. Perhaps this was Darius’s attempt to create a symbol of the assured continuity of his line. Apadana hall and the adjacent structures in the complex are believed to have been designed to host large number of people. In fact, halls of Persepolis could at any one time host some ten thousand visitors easily with the king and the royal staff seated appropriately.[16]

The grandeur of Persepolis is in its architectural details, its impressive, tall, and upright columns, in its skilfully crafted reliefs depicting people from all walks of life, and from all corners of the empire, and most importantly in its historical importance as both a political and a social center of Achaemenid royal life.

Engineering

Overview

Persepolis Fortifications (PF) Tablets, dating to between 509 and 494 B.C.E. are ancient Persian documents that describe many aspects of construction and maintenance of the Persepolis.[17] The tablets are important because they highlight two important aspects of the Achaemenid life and the construction of Persepolis: Firstly, that the structure was created by workers, who were paid rations or wages, and secondly the structure had an intricate system of engineering involving weight bearing and architectural elements, and most notably an irrigation system composed of a system of closed pipes and open aqueducts. The following text from PF 1224, delineates both points:

32 BAN (9.7 litres) of grain…the high priest at Persepolis… received and gave (it as) bonus to post-partum Greek women at Persepolis, irrigation (workers), whose apportionment are set….[17]

Water Technologies

The runoff and sewer network of Persepolis are among the most complex in the ancient world. Persepolis is constructed on the foot of a mountain (Rahmat Mountain), with an elevated terrace that is partially man made and partially part of the mountain complex. As Persepolis was in essence an important cultural center often used by the beginning of the spring during the festival of Nowruz it enjoyed great precipitation and water runoffs from the molten ice and snow. The sewer network assumed great importance at this critical time as it was meant to both handle the water flow downward from higher areas as well as manage the inhabitant’s sewage runoffs, and their water needs.[18]

In order to prevent flooding, the Achaemenids used two engineering techniques to divert snowmelt and mountain runoff: The first strategy was to collect the runoff in a reservoir that was a well with a square opening with dimensions of 4.2 m for the square opening, and a depth of 60 m, allowing a volume of 554 cubic meters, or 554,000 liters, (60 x 4.2 x 4.2) of runoff to be collected. The water would be diverted toward the reservoir via multiple masonry gutters strategically located around the structure. The second strategy was to divert water away from the structure, should the reservoirs be filled to capacity; this system used a 180 m long conduit, with 7 m width, and 2.6 m depth located just west of the site.[18]

The water system however was far more complex than just the reservoirs and the water conduits and involved a very sophisticated ancient system of closed pipes and irrigation. The irrigation was divided into five zones, two serving north part of the structure and three the southern part. Amazingly the irrigation system was designed to be harmonious with the structure so that at places there were central drainage canals in the center of the columns and small draining holes and conduits on each floor that would take the water out of roof, each floor, and the sewage portals into an underground sewage network and away from the structure.[18]

The five zones (I–V) all possessed a runoff capacity of 260 L/s (liter/second) which is certainly more than the amount needed for handling mountain runoff indicating that the system was also used for water supply to the inhabitants, sewage management, and even irrigation of the gardens around the structure.[18]

Structural Technologies

In order for such a massive structure to have functioned properly it meant that the weight of the roof, columns and indeed the terrace had to be distributed evenly. Construction at the base of the mountain offered some structural support. The ceiling material was a composite application of wood and stone decreasing its overall weight. Extensive use of stone in Persepolis, not only guaranteed its structural integrity for the duration of its use but also meant that its remains lasted longer than the mud-bricks of Susa palaces.

History

Scholars agree that it was Darius the Great who initiated the construction and expansion of the Persepolis project, however German archaeologist Ernst E. Herzfeld, believed that it was Cyrus the Great who chose the site for the construction, although it ultimately came down to Darius the Great to finish the construction and create its impressive buildings. Excavations on behalf of the Oriental Institute of Chicago University, headed by Herzfeld in 1931 and later cooperation by Eric F. Schmidt in 1933 led to some of the most impressive uncovering of Achaemenid artifacts, palaces, and structures. Herzfeld felt that the site of Persepolis was made for special ceremonies and was meant to convey the power of the Achaemenid empire to its subject nations.[9]

On some accounts, Persepolis was never officially finished as its existence was cut short by Alexander the Great, who in a fit of anger, ordered the burning of the city in 330 B.C.E. Started originally by Darius the Great a century earlier, the structure was constantly changing, receiving upgrades from subsequent Persian monarchs, and undergoing renovation to maintain its impressive façade. After the burning of the city, Persepolis was deserted and it was relatively lost to history until the excavations of Herzfeld, Schmidt, and the Chicago team uncovered it in the 1930s. This great historical artifact is unfortunately at serious risk of “irreparable damage”[3] from neglect, the elements, and vandalism.

Persepolis was by no means the only large scale Achaemenid project, as Susa also hosted a similar structure initiated by Darius for similar ceremonial purposes. However, that history is able to enjoy the remains of Persepolis as opposed to meager remnants of Susa, owes partly to selection of stone in construction of Persepolis over mud-brick in Susa, and the fact that it had been relatively uninhabited, protecting it from wear and tear of inhabitants. Politically, Persepolis also was a significant find because nearby discovery of Naqsh-e Rustam, the Persian necropolis home to Darius the Great shed light on the significance it has had as one of the major capitals of the empire.[5] Naqsh-e Rustam would not only house Darius the Great, but also his son Xerxes the Great, Artaxerxes I, and Darius II as well. The necropolis complex was looted following invasion of Alexander, and possibly in the Sassanid period and during the Arab invasion.

During the time of Shah of Iran, the structure enjoyed protection and coverage as Mohammad Reza Shah appeased to its royal and national symbolism. During this time period many western politicians, poets, artists, and writers were gravitated to Iran, and Persepolis, either as a function of the political relations with the Iranian monarchy or to report on, or visit the ruins. Such figures include the procession of international dignitaries attending the 2,500 year celebration of the Persian Empire held by Shah, as well as individual visits by such figures as Heinrich Lübke of Germany, and Ralph Graves of Life magazine. In an article in “Life“ in 1971, Graves describes his experience at Persepolis in the following way:

When you see Persepolis for the first time as I did, facing Marvdasht, you are likely to be disappointed but once inside the ruins themselves you are overwhelmed by the still-proud soaring columns, and by the quality and the fresh state of the bas-relief carvings which are certainly among the finest in the history of the world’s art. But mostly you are transfixed by the sudden realization that all this happened 24 centuries ago, and that people from every nation in the known world of the time had stood in the same place and felt the same.[19]

Vandalism

Throughout history there have been instances of neglect or vandalism in Persepolis. The most notable historical figure to vandalize this structure was Alexander the Great, who after entering Persepolis in 330 B.C.E. called it the “most hateful city in Asia” and allowed his Macedonian troops to pillage it.[20] Despite this stern hatred, Alexander also admired the Persians as is obvious through his respect for Cyrus the Great, and his act of giving a dignified burial to Darius III. Years later upon revisiting the city he had burnt, Alexander would regret his action. Plutarch depicts the paradoxical nature of Alexander when he recounts an anecdote in which Alexander pauses and talks to a fallen statue of Xerxes the Great as if it were a live person:

Shall I pass by and leave you lying there because of the expeditions you led against Greece, or shall I set you up again because of your magnanimity and your virtues in other respects?[21]

In retrospect, it must be understood that despite his momentary lapse of judgment and his role as having been the single most significant figure to bring an end to Persepolis, Alexander is not by any means the only. Many individuals in the following centuries would damage Persepolis including thieves and vandals during the Sassanid era. When the Arab armies invaded in the seventh century, they took to causing civil disturbances, religious persecution of Persians, and burning of the books. That no clear record of their vandalism remains to date, is most likely due to their destruction of books and historical records.[22]

During the colonial era, and in WWII, the structure would also suffer vandalism at the hands of the Allies. Natural causes such as earthquakes and winds have also contributed to the overall demise of the structure.[23]

The first French excavation in Susa carried out by the Dieulafoys and the looting and the destruction of Persian antiquities by the so-called archeologists had a deep impact on the site. Jane Dieulafoy writes in her diary:

Yesterday I was gazing at the huge stone cow found recently; it weighs around 12,000 kilos! It is impossible to move such an enormous mass. I couldn’t control my anger. I took a hammer and started striking the stone beast. I gave it some ferocious blows. The head of the pillar burst open like ripe fruit.

Even to date the structure is not safe from destruction and vandalism. After the Iranian revolution, a group of fundamentalists serving Khomeini, including his right-hand man Sadegh Khalkhali, tried to bulldoze both the renown Persian poet, Ferdowsi’s tomb, and Persepolis, but they were stopped by the provisional government.[24]

The pictures above highlights only some of these unfortunate acts of vandalism mostly by foreign visitors from the late 1800s to mid-1900s. Currently the structure is at high risk of “irreparable damage.”[3]

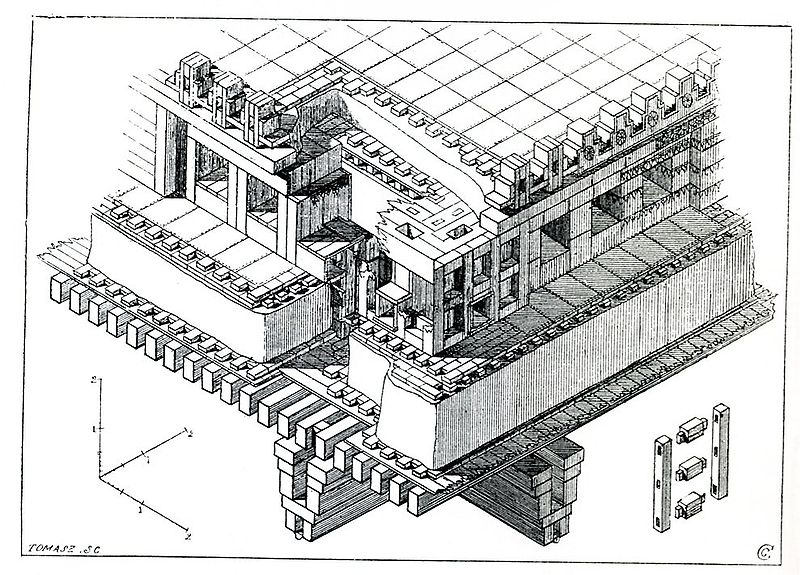

Virtual Reconstruction

French archaeologist, Egyptologist, and historian Charles Chipiez (1835–1901) has created some of the most advanced virtual drawings of what Persepolis would have looked like as a metropolis of the Persian Empire. The following mini-gallery depicts his virtual recreations.[25]

The image above is a view of the “Talar-i-Takht” or the 100 columns hall of Persepolis. Note on the far left portion of the image, the famous “lamassu” (or chimeric man, lion, eagle beast) greeting the visitors (look below for a picture of a lamassu). Chipiez’s drawings delineate his technical prowess and attention to details.

The image above is Chipiez’s drawing of the columns, their capital ornation, and roof structure of the palace of Darius in Persepolis, also known as “Tachar.” Note the adorsed bull details, as well as the use of wood in construction of the roof. This explains why the palace caught fire when Alexander the Great, set it aflame.

The image above is a more detailed, technical drawing of the “Talar-i-Takht” or the 100 column hall. Note the layering of the roof, the detailing on the edges of the roof, the window structures, and the technical detailing of the construction poles.

The image above, is a panoramic view of the outside of the palace of Darius the Great in Persepolis. Details of the Persepolis reliefs are depicted as one can note the symbolic scenes of lions attacking bulls, accompanied by two groups of Persian soldiers protecting (symbolically in this case) the infrastructure above.

Susa

Overview

Susa was an ancient city (5500 B.C.E) even by the time of the Achaemenids. Susa became a part of the Achaemenid Empire in 539 B.C.E., and was expanded upon by Darius the Great with construction of Palace of Darius, and later development of palace of Artaxerxes II. The palace had a unique Apadana, resembling the one in Persepolis, except this hall was much larger than its Persepolis counterpart covering some 9,200 square meters.[26] Cyrus the Great chose Susa as a site for one of his fortifications creating a wall there that was significantly taller than older walls made by the Elamites. This choice might have been to facilitate the trade from Persian Gulf northward.[9] What remains in way of structure from this once active capital, are five archaeological mounds, today located in modern Shush, in southwestern Iran, scattered over 250 hectares.[27]

Structural Details

Darius’s design of his palace in Susa would resemble Persepolis structurally and aesthetically but would incorporate more of a local flair. The structure hosted a large hall of throne or Apadana similar to the Apadana of the Persepolis. This Susa version of Apadana would be composed of three porticoes at right angles to each other, one of which was closed in all three sides by the walls, and only open in its southward direction. The palace was decorated with reliefs in enameled terra-cotta of lions walking.[26]

Intricate scenes depicting archers of king Darius would decorate the walls, as well as motifs of nature such as double-bulls, unicorns, fasciae curling into volutes, and palms disposed as a flower or a bell. The archers in particular depict a unique symbiosis of Persian, Ionian and Greek artistry of the time probably reflecting the origin of the artists who were originally hired by Darius the Great, and their personal reflections on the finished work.[26] Perhaps the most striking terra-cotta relief is that of the griffin, depicting a winged creature resembling a lion with wings of an eagle (picture not shown here). The terra-cotta brick reliefs were decorated with lively dye colorations often giving them a lifelike quality.

History

Architecturally, the palace of Darius in Susa, was the epitome of the Persian architecture at the height of the empire’s growth. Originally erected by Darius, and extensively renovated and modified by Artaxerxes II, it was meant to reflect the same opulence and prestige as Persepolis. This was Darius the Great’s attempt to decorate his summer capital of Susa and to show case its glory. French archaeologist Marcel-Auguste Dieulafoy discovered the remnants of the palace of Darius, among the ruins of Susa producing the artifacts of this once magnificent structure now at display in the Louvre museum, France. He also wrote a series of architectural observations known as “L’Art antique de la Perse” which made a significant impression on the art community as to the intricacy of the Achaemenid architecture.[26] Although Dieulafoy and his wife Jane, made significant contributions in way of excavation, Susa remains were noted by many observers years before and were in fact officially noted by William K. Loftus in 1852.[27]

Susa was a wealthy city by the time Alexander the Great invaded it, and it is said that he required 10,000 camels and 20,000 donkeys to carry away the treasures.[9] For the most part the architectural wealth of Susa lies in its palaces, and ceremonial structures most of which have been eroded away by time or wear and tear. Today the most important remnants of the Achaemenid contribution to the architecture of ancient Susa are found in remnants of the Palace of Darius the Great in the original excavation site, or hosted in foreign nations’ museums as Persian artifacts. Today the archaeological remains of the structure remain exposed to the elements, wear and tear, and human activity, and it seems that remains of Susa would be forever lost to the humankind, except perhaps for few selected pieces on display at the Louvre or foreign nations’ museums.

Naqsh-e Rustam

Overview

Naqsh-e Rustam is an archaeological site located about 6 kilometers to the northwest of Persepolis in Marvdasht region in the Fars province of Iran.[28] Nash-e Rustam acts as a necropolis for the Achaemenid kings, but is a significant historical entity in that it also housed ancient Elamite relief, as well as later relief by the Sassanid kings. Naqsh-e Rustam is not the actual name of this massive structure, but is the New Persian compound word composed of “Naqsh” meaning “face”, or “facade”, and “Rustam” referring to the hero of the Persian epic Shahnameh. The Elamites, Achaemenids, and the Sassanids lived centuries before the drafting of the Shahnameh by the Persian poet Ferdowsi, and therefore the name is a misnomer, the result of the great amnesia of Persians about their ancient past, that settled over them after being conquered by the Arabs.[29]

The name therefore is a retrospective creation, due to lack of historical documents and lack of any inclusive knowledge of its origin. In ancient Persia, this structure would overlook the now long gone city of Istakhr easily accessible from Persepolis. Istakhr had a religious role as it was the place where Achaemenids held their reverence of the water goddess Anahita. The structure is carved into a native limestone rock mountain, and houses the burial chambers of Darius the Great, Xerxes I, Artaxerxes I, and Darius II, all Achaemenid monarchs of Persia. There is also an incomplete tomb, as only its lower cruciform arm is carved out of the rock, while the rest is unfinished. It is speculated to belong to king Darius III.[28][29]

The kings were interred behind a facade and rock relief, that would resemble an accurate depiction of the king’s own palace and its structural details. The accuracy of the facade and its association with the actual structure of the kings’ palaces is so close that they almost produce a view of how the structures would have looked before time reduced them to remains; Tomb of Darius the Great, for instance mirrors his palace in Persepolis, the “Tachar” even in scale and dimensions.[29]

The tombs are carved into the mountain’s side, in form of a cross (Old Persian: chalipa), depressed into the mountain’s limestone background, and elevated from the ground. The relief which is found in the depressed cruciform is that which depicts the respective king’s palace, and also depicts on its roof, the relief figure of the king praying, to Ahuramazda or what most believe is a reference to the Zoroastrian icon, Faravahar.[29]

One of the enigmatic features of the complex is a cubical, stone structure standing 12.5 meters tall, and around 7 meters wide, called the “Ka’ba-ye Zartosht” translating to the “Cube of Zoroaster” believed to have been constructed during the Acahemenid era and modified and changed during the Sassanid era. The structure is cubical in base, with blind impressions on the side resembling windows, and a ruined staircase leading to a small door in the front leading to a completely empty interior.[28][29] There are varied speculations as to its function discussed below.

The structure also once housed an ancient Elamite relief which has been almost entirely replaced by the Sassanid reliefs. Today but a figure of a man remains of the Elamite contribution to this mountain. The later Sassanids, also created their own historical signature on the structure, called the Naqsh-e Rajab. Though numerous and very detailed, the study of the Sassanid architectural achievements sheds light on some of the architectural achievements during the second Persian empire’s reign.

Ka’ba-ye Zartosht

This enigmatic structure stands erect around 12.5 meters tall (~ 35 feet), with a linear, cubical shape and a square base (~ 22 feet in sides),[7] constructed in what is essentially a dug out rectangular depression, having on all but one of its sides, four rectangular depressions resembling blind windows, and multiple minute rectangular depressions in the façade interdispersed among the blind windows as well as the side housing the staircase. The staircase leads to a small door (5 feet by 6 feet in dimensions) opening to an interior apartment of about 12 feet square.[7] The structure’s roof houses a minimal entablature of a repeating square pattern.[7] The entire structure is posited on a raised stone platform that is composed of a few stone slabs, in a sequentially smaller yet in a concentric, pyramidally shaped succession. This structure is enigmatic, both in its aesthetic choice seen in its rather odd design, and façade, as well as its location, and supposed function.

From one perspective, its proximity to the kings’ tombs, and its simple design, is by some scholars thought to indicate that the cube was a Zoroastrian temple, and the Naqsh-e Rustam was more than a mere place for grieving of the deceased kings, but a grand festive center where crowds would gather on festive days to observe the king pray to Ahuramazda, and bask in the structure’s magnitude while praying to Ahuramazda.[29] This would certainly be logical as the city was also adjacent to Istakhr, a major religious and cultural center. The concept of the temple being used as a fire sanctuary, is however not likely because there is no general ventilation for smoke and gasses, and also that it differs so drastically, architecturally and aesthetically from other well known contemporary temple sites in Pars.[30]

Curiously the design although unique, is not the only one of its kind. Located not far away from the Cube of Zoroaster, there exists in Pasargadae, even to date, remnants of a structure that is very similar in its square shape and design to the “Cube of Zoroaster“, called “Zendan-i-Suleiman.”[7] The name “Zendan-i-Suleiman,” is a compound word composed of the words, “Zendan” which is Persian for “jail”, and “Suleiman” which is a local Persian dialect name of the King Solomon, translating to “Jail of Solomon.” Structurally both “Jail of Solomon” and “Cube of Zoroaster” have the same cubic shape, and even resemble each other in the most minute of details, including facade, and dimensions. The name “Jail of Solomon” is of course a misnomer since Solomon never did erect this structure. The term must have come as a result of a Persian tactic advised by local Persians, to protect both Cyrus the Great’s tomb, and the surrounding structures including this temple, from invading Arabs’ destruction, by calling the mausoleum, the “tomb of Solomon’s mother” and the temple in Pasargadae, the “Jail of Solomon.”[12]

Just like the “Cube of Zoroaster”, the function of the “Solomon’s Jail” is not well understood. There are theories about the structures being used as a depository of objects of dynastic or religious importance as well as theories of it being a temple of fire.[7] It should also be noted, that the structures as they exist today are not simply the work of the Achaemenid architects and have been modified, and improved by the Sassanids, who also used them for their festive, and political needs.

Behistun Inscription

Carved high in Mount Behistun of Kermanshah, one can find the Behistun inscription, a text etched into the stone of the mountain describing the manner in which Darius became the king of Persia, after the previous ruler (Cambyses II), and how he overthrew the magus usurper of the throne.[31] In this inscription Darius also details his satraps and delineates his position as the king and emperor of the Persian empire.

Architecturally speaking, the Behistun inscription is a massive project, that entailed cutting into the rough edge of the mountain in order to create bas-relief figures as seen in the pictures above. The Behistun mountain, rises up to some 1700 feet as part of the Zagros mountain chains in Iran. The mountain’s location is ideal being close to both Ecbatana and Babylonia.[32] The bas-relief itself is located some 300 feet above the base of the mountain. The figures represent two of the king’s soldiers, the king himself standing over a fallen usurper and captives of several nations possibly dissidents, or co-conspirators. The inscription itself is written in cuneiform character in Old Persian, Babylonian, and Median.[32]

The inscription is interpreted and deciphered with the help of many intellectuals and scholars, but the Orientalist Sir Henry Rawlinson is credited as being most critical in the process of deciphering the piece.[32] Part of why the understanding of the text is so vivid today is owed to Darius the Great himself, for he wrote the message of the inscription in three language, and so allowed the modern scholars to decipher one language and follow through the other two, since the message was essentially similar in all three forms. In this sense, the Behistun inscription is not only a significant architectural work, but also a significant linguistic tool, as important to the old world understanding of ancient Persia and its languages, as Rosetta Stone is to understanding ancient Egypt and its languages.[33]

Notes

- Charles Henry Caffin (1917). How to study architecture. Dodd, Mead and Company. p. 80.

- Fallah’far, Sa’id (2010). The Dictionary of Iranian Traditional Architectural Terms Kamyab Publications. p. 44. Archived from the original on 2012-07-13.

- Marco Bussagli (2005). Understanding Architecture. I.B.Tauris. p. 211.

- Charles Gates (2003). Ancient cities: the archaeology of urban life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome. Psychology Press. p. 186.

- Ronald W. Ferrier (1989). The Arts of Persia. Yale University Press. pp. 27–8.

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre (2006). “Pasargadae“. Retrieved December 26, 2010.

- James Fergusson (1851). The palaces of Nineveh and Persepolis restored: an essay on ancient Assyrian and Persian architecture, Volume 5. J. Murray. pp. 214–216 & 206–209 (Zoroaster Cube: pp. 206).

- ((Grk.) Lucius Flavius Arrianus) (En.) Arrian – (trans.) Charles Dexter Cleveland (1861). A compendium of classical literature:comprising choice extracts translated from Greek and Roman writers, with biographical sketches. Biddle. p. 313.

- Aedeen Cremin (2007). Archaeologica: The World’s Most Significant Sites and Cultural Treasures. frances lincoln Ltd. pp. 227–29.

- Abraham Valentine Williams Jackson (1906). Persia past and present. The Macmillan Company. p. 278.

- Ralph Griffiths; George Edward Griffiths (1816). The Monthly review. Printers Street, London. p. 509.

- Andrew Burke; Mark Elliot (2008). Iran. Lonely Planet. p. 284.

- James D. Cockcroft (1989). Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, Shah of Iran. Chelsea House Publishers.

- Ralph Graves (October 15, 1971). “A stunning setting for a 2500th anniversary”. Life magazine.

- Ilya Gershevitch (1985). The Cambridge history of Iran: The Median and Achaemenian periods, Volume 2. Cambridge University Press. pp. 392–398.

- R. Schmitt; D. Stronach (December 15, 1986). “APADANA“. Encyclopedia Iranica. Retrieved Jan 23, 2011.

- George Boys-Stones; Barbara Graziosi; Phiroze Vasunia (2009). The Oxford handbook of Hellenic studies. Oxford University Press US. pp. 42–47.

- L. Mays; M. Moradi-Jalal; et al. (2010). Ancient Water Technologies. Springer. pp. 95–100.

- Ralph Graves (October 15, 1971). “A stunning setting for a 2500th anniversary”. Life magazine.

- Laura Foreman (2004). Alexander the conqueror: the epic story of the warrior king, Volume 2003. Da Capo Press. p. 152.

- O’Brien, John Maxwell (1994). Alexander the Great: The Invisible Enemy: A Biography. Psychology Press. p. 104.

- Solomon Alexander Nigosian (1993). The Zoroastrian faith: tradition and modern research. McGill-Queen’s Press. pp. 47–48.

- N. N. Ambraseys; C. P. Melville (2005). A History of Persian Earthquakes. Cambridge University Press. p. 198.

- Reza Aslan (April 30, 2006). “The Epic of Iran”. New York Times. Retrieved Jan 30, 2011.

- Georges Perrot; Charles Chipiez (1892). History of art in Persia. Chapman and Hall, limited. pp. 336–43 & others.

- Giulio Carotti (1908). A History of Art. Duckworth & Co. pp. 94–7.

- David Noel Freedman; Allen C. Myers; Astrid B. Beck (2000). Eerdmans dictionary of the Bible. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 1258.

- Gene Ralph Garthwaite (2005). The Persians. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 51–55.

- Paul Kriwaczek (2004). In Search of Zarathustra: Across Iran and Central Asia to Find the World’s First Prophet. Random House, Inc. pp. 88–90.

- Ali Sami (1956). Pasargadae: the oldest imperial capital. Musavi Printing Office. pp. 90–94.

- John Kitto; Henry Burgess; Benjamin Harris Cowper (1856). The journal of sacred literature and Biblical record, Volume 3. A. Heylin. pp. 183–5.

- Philip Smith (1865). A history of the world from the earliest records to the present time: ancient history, Volume 1. D. Appleton. p. 298.

- J. Poolos (2008). Darius the Great. Infobase Publishing. pp. 38–9.

Originally published by Wikipedia, 01.23.2011, under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.