Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

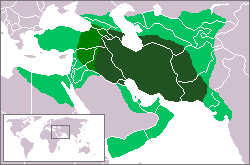

Sassanid Empire or Sassanian Dynasty is the name used for the third Iranian dynasty and the second Empire. The dynasty was founded by Ardashir I after defeating the last Parthian (Arsacid) king, Artabanus IV Ardavan). It ended when the last Sassanid Shahanshah (King of Kings), Yazdegerd III (632-651), lost a 14-year struggle to drive out the expanding Islamic empires. The Empire’s territory encompassed all of what is now Iran, Iraq, Armenia, Afghanistan, eastern parts of Turkey, and parts of Syria, Pakistan, Caucasia, Central Asia and Arabia. The Sassanids called their empire Eranshahr “Empire of the Aryans (Persians)”. The Sassanid era is considered to be one of Iran’s most important and influential historical periods. In many ways the Sassanid period witnessed the highest achievement of Persian civilization, constituting the last great Iranian Empire before the Muslim conquest. Persia influenced Roman civilization considerably during the Sassanids’ times, and the Romans reserved for the Sassanid Persians alone the status of equals.

Often tolerant of religious minorities, Jewish life flourished during the Sassanid period, producing the Babylonian Talmud. Their cultural influence extended far beyond the empire’s territorial borders, reaching Western Europe, Africa, China and India and played a prominent role in the formation of European and Asiatic medieval art. This influence carried forward to the early Islamic world with the Muslim conquest of Iran, including the idea of a paid, professional army. Although often engaged in conquest, the Sassanids also entered into peace treaties and engaged in widespread trade. They served humanity as cultural catalysts, helping to create a more interconnected and inter-dependent world.

History

Origins and Early History (205-310 CE)

Scanty and conflicting stories obscure the end of the Arsacids and the rise of the Sassanids.[1] The Sassanid Dynasty was established by Ardashir I, a descendant of a line of the priests of goddess Anahita in Istakhr, who was governor of Persis at the start of the third century. However, his ancestry is a little vague, since it is unclear whether he was a natural or adopted son of Papag, and whether Sasan was the eponymous founder of the dynasty or Ardashir’s real father or father-in-law. In general, sources are not consistent about the relationships between the early Sassanids, Sassan, Papag, Ardashir and Shapur.[2]

Papag was originally the ruler of a small town called Kheir, but by 200 C.E. had deposed Gocihr, the last king of the Bazrangids (the local rulers of Persis as a client of the Arsacids) and appointed himself as ruler. His mother, Rodhagh, was the daughter of the provincial governor of Persis. Papag and his eldest son Shapur expanded their power over all of Persis. The subsequent events are unclear, due to the sketchy nature of the sources. It is certain, though, that following the death of Pabag, Ardashir who was then governor of Darabgird, became involved in a power struggle of his own with his elder brother Shapur. The sources tell us that Shapur, leaving for a meeting with his brother, was killed when the roof of a building collapsed on him. By 208 over the protests of his other brothers, who were put to death, Ardashir declared himself ruler of Persis.[3]

Moving his capital further to the south of Persis, Ardashir founded Ardashir-Khwarrah (formerly Gur, modern day Firouzabad). The city, well supported by high mountains and east to defend through narrow passes, became the center of Ardashir’s efforts to gain more power. The city was surrounded by a high, circular wall, probably copied from Darabgird’s; on the north-side was a large palace, remains of which still survive. After establishing his rule over Persis, Ardashir I rapidly extended his territory, demanding fealty from the local princes and gaining control over the neighboring provinces of Kerman, Isfahan, Susiana, and Mesene. When this expansion came to the attention of Artabanus IV, the Parthian king, he ordered the governor of Khuzestan to march against Ardashir in 224. This resulted in a major victory for Ardashir. Artabanus himself marched against Ardashir I in 224. Their armies clashed at Hormozgan, where Artabanus was killed and Ardashir I went on to invade the western provinces of the now defunct Parthian Empire.

A dynastic struggle for the Parthian throne at the time helped Ardashir consolidate his authority in the south with little or no interference. This was also assisted by the geography of the Fars province, which was separate from the rest of Iran,[4] Crowned in 224 at Ctesiphon as the sole ruler of Persia, Ardashir took the title Shahanshah, or “King of Kings” (the inscriptions mention Adhur-Anahid as his “Queen of Queens,” but her relationship with Ardashir is not established). Thus 400-years of Parthian rule ended and four centuries of Sassanid rule began.[5]

Over the next few years, following local rebellions around the empire, Ardashir I further expanded his empire to the east and northwest, conquering the provinces of Sistan, Gorgan, Khorasan, Margiana (in modern Turkmenistan), Balkh, and Chorasmia. He also added Bahrain and Mosul to Sassanid possessions. Later Sassanid inscriptions also claim the submission of the Kings of Kushan, Turan, and Mekran to Ardashir, although based on numismatic evidence, it is more likely that these actually submitted to Ardashir’s son, the future Shapur I. In the west, assaults against Hatra, Kingdom of Armenia, and Adiabene met with less success. In 230 he raided deep into Roman territory, and a Roman counter-offensive two years later ended inconclusively, although the Roman emperor, Alexander Severus, celebrated a triumph in Rome.[6]

Ardashir I’s son Shapur I continued to expand the empire, conquering Bactria and the western portion of the Kushan Empire and led several campaigns against Rome. Invading Roman Mesopotamia, Shapur I captured Carrhae and Nisibis, but in 243 the Roman general Timesitheus defeated the Persians at Rhesaina and regained the lost territories.[7] The emperor Gordian III’s (238-244) subsequent advance down the Euphrates was defeated at Meshike (244), leading to Gordian’s murder by his own troops and enabling Shapur to conclude a highly advantageous peace treaty with the new emperor Philip the Arab, by which he secured the immediate payment of 500,000 denari and further annual payments. Shapur soon resumed the war, defeated the Romans at Barbalissos (252), and then probably took and plundered Antioch.[7] Roman counter-attacks under the emperor Valerian ended in disaster when the Roman army was defeated and besieged at Edessa and Valerian was captured by Shapur, remaining his prisoner for the rest of his life. Shapur celebrated his victory by carving the impressive rock reliefs in Naqsh-e Rostam and Bishapur, as well as a monumental inscription in Persian and Greek in the vicinity of Persepolis. He exploited his success by advancing into Anatolia (260), but withdrew in disarray after defeats at the hands of the Romans and their Palmyrene ally Odaenathus, suffering the capture of his harem and the loss of all the Roman territories he had occupied.[8]

Shapur had intensive development plans; he founded many cities, some settled in part by emigrants from the Roman territories, including Christians who could exercise their faith freely under Sassanid rule. Two cities, Bishapur and Nishapur, are named after him. He particularly favored Manichaeism, protected Mani (who dedicated one of his books, the “Shabuhragan,” to him) and sent many Manichaean missionaries abroad. He also befriended a Babylonian rabbi called Shmuel. This friendship was advantageous for the Jewish community and gave them a respite from the oppressive laws enacted against them. Later kings reversed Shapur’s policy of religious tolerance. Under pressure from Zoroastrian Magi and influenced by the high-priest Kartir, Bahram I killed Mani and persecuted his followers. Bahram II was, like his father, amenable to the wishes of the Zoroastrian priesthood.[9] During his reign the Sassanid capital Ctesiphon was sacked by the Romans under emperor Carus, and most of Armenia, after half a century of Persian rule, was ceded to Diocletian.[10]

Succeeding Bahram III (who ruled briefly in 293), Narseh embarked on another war with the Romans. After an early success against the Emperor Galerius near Callinicum on the Euphrates in 296, Narseh was decisively defeated in an ambush while he was with his harem in Armenia in 298. In the treaty that concluded this war, the Sassanids ceded five provinces east of the Tigris and agreed not to interfere in the affairs of Armenia and Georgia.[11] Following this crushing defeat, Narseh resigned in 301 and died in grief a year later. Narseh’s son Hormizd II suppressed revolts in Sistan and Kushan, but was unable to control the nobles; he was killed by Bedouins while hunting in 309.

First Golden Era (309-379 CE)

Following Hormizd II’s death, Arabs from the south started to ravage and plunder the southern cities of the empire, even attacking the province of Fars, the birthplace of the Sassanid kings. Meanwhile, Persian nobles killed Hormizd II’s eldest son, blinded the second, and imprisoned the third (who later escaped to Roman territory). The throne was reserved for Shapur II, the unborn child of one of Hormizd II’s wives, who was crowned in utero: the crown was placed upon his mother’s stomach. Until Shapur II came of age, the empire was controlled by his mother and the nobles. Once he assumed power, he quickly proved to be an active and effective ruler.

Shapur II first led his small but disciplined army south against the Arabs, whom he defeated, securing the southern areas of the empire.[12] He then started his first campaign against the Romans in the west, where Persian forces won a series of battles but were unable to make territorial gains due to the failure of repeated sieges of the key frontier city of Nisibis and Roman success in retaking the cities of Singara and Amida after they fell to the Persians. These campaigns were halted by nomadic raids along the eastern borders of the empire, which threatened Transoxiana, a strategically critical area for control of the Silk Road. Shapur therefore marched east toward Transoxiana to meet the eastern nomads, leaving his local commanders to mount nuisance raids on the Romans. He crushed the Central Asian tribes, and annexed the area as a new province. He completed the conquest of the area now known as Afghanistan. Cultural flourished followed this victory, and Sassanid art penetrated Turkistan, reaching as far as China. Shapur, along with the nomad King Grumbates, started his second campaign against the Romans in 359, and soon succeeded in taking Singara and Amida again. In response to this, the Roman emperor Julian struck deep into Persian territory, and defeated Shapur’s forces at Ctesiphon. However, having failed to take the capital, he was killed while trying to retreat back to Roman territory. His successor Jovian, trapped on the east bank of the Tigris, had to agree to hand over all the provinces which the Persians had ceded to Rome in 298 as well as Nisibis and Singara, in order to secure safe conduct for his army out of Persia.

Shapur II pursued a harsh religious policy. Under his reign the collection of the Avesta, the sacred texts of Zoroastrianism, was completed, heresy and apostasy were punished, and Christians were persecuted. The latter was a reaction against the Christianization of the Roman Empire by Constantine the Great. Shapur II, like Shapur I, was amicable towards Jews, who lived in relative freedom and gained many advantages in his period. At the time of Shapur’s death, the Persian Empire was stronger than ever, with its enemies to the east pacified and Armenia under Persian control.

Intermediate Era (379–498 CE)

From Shapur II’s death until Kavadh I’s first coronation was a largely peaceful period with the Romans, interrupted only by two brief wars, the first in 421–422 and the second in 440.[13] Throughout this era Sassanid religious policy differed dramatically from king to king. Despite a series of weak leaders, the administrative system established during Shapur II’s reign remained strong, and the empire continued to function effectively.

Shapur II died in 379, leaving a powerful empire to his half-brother Ardashir II (379-383; son of Vahram of Kushan) and his son Shapur III (383-388). Neither demonstrated their predecessor’s talent. Bahram IV (388 – 399), although not as inactive as his father, still failed to achieve anything of significance for the empire. During this time Armenia was divided by treaty between the Roman and Sassanid empires, the Sassanids reestablished their rule over Greater Armenia, with the Byzantine Empire holding a small portion of western Armenia.

Bahram IV’s son Yazdegerd I (399-421) is often compared to Constantine I. Like him, he was physically and diplomatically powerful and an opportunist. Like Constantine the Great, Yazdgerd I practiced religious tolerance and provided freedom for the rise of religious minorities. He stopped the persecution of Christians and even punished nobles and priests who persecuted them. His reign marked a relatively peaceful era. He made lasting peace with the Romans and even took the young Theodosius II (408-450) under his guardianship. He also married a Jewish princess who bore him a son called Narsi.

Yazdegerd I’s successor was his son Bahram V (421-438), one of the most well-known Sassanid kings and the hero of many myths which persisted even after the destruction of the Sassanid empire. Bahram V, better known as Bahram-e Gur, gained the crown after Yazdgerd I’s sudden death (or assassination) against the opposition of the grandees with the help of al-Mundhir, the Arabic dynast of al-Hirah. Bahram V’s mother was Soshandukht, the daughter of the Jewish Exilarch. In 427 he crushed an invasion in the east by the nomadic Hephthalites, extending his influence into Central Asia, where his portrait survived for centuries on the coinage of Bukhara (in modern Uzbekistan). Bahram V deposed the vassal King of the Persian part of Armenia and made it a province.

Persian tradition relates many stories of Bahram V’s valor, beauty, of his victories over the Romans, Turks, Indians and Africans, and of his adventures in hunting and in love. He is called Bahram-e Gur, Gur meaning Onager (an Asiatic wild ass), on account of his love for hunting and, in particular, hunting onagers. He symbolized a king in the height of a golden age. He had won his crown by competing with his brother and spent time fighting foreign enemies, but mostly kept himself amused by hunting and court parties with his famous band of ladies and courtiers. He embodied royal prosperity. During his time the best pieces of Sassanid literature were written, notable pieces of Sassanid music were composed, and sports such as polo became royal pastimes.

Bahram V’s son Yazdegerd II (438 – 457) was a just, moderate ruler but, in contrast to Yazdegerd I, practiced a harsh policy towards minority religions, particularly Christianity.[14] At the beginning of his reign, Yazdegerd II gathered a mixed army of various nations, including his Indian allies, and attacked the Eastern Roman Empire in 441, but peace was soon restored after small-scale fighting. He then gathered his forces in Neishabur in 443 and launched a prolonged campaign against the Kidarites. Finally after a number of battles, he crushed the Kidarites and drove them out beyond Oxus river in 450.[15]

During his eastern campaign, Yazdegerd II grew suspicious of the Christians in the army and expelled them all from the governing body and army. He then persecuted the Christians and, to a much lesser extent, the Jews.[16] In order to reestablish Zoroastrianism in Armenia, he crushed an uprising of Armenian Christians at the Battle of Vartanantz in 451. The Armenians, however, remained primarily Christian. In his later years, he was engaged yet again with Kidarites until his death in 457. Hormizd III (457 – 459), younger son of Yazdegerd II, ascended to the throne. During his short rule, he continually fought with his elder brother Peroz, who had the support of nobility[16] and with the Hephthalites in Bactria. Peroz killed him in 459.

In the beginning of the fifth century, the Hephthalites (White Huns), along with other nomadic groups, attacked Persia. At first Bahram V and Yazdegerd II inflicted decisive defeats against them and drove them back eastward. The Huns returned at the end of fifth century and defeated Peroz I (457-484) in 483. Following this victory the Huns invaded and plundered parts of eastern Persia for two years, exacting tribute for several years.

These attacks brought instability and chaos to the kingdom. Peroz I tried again to drive out the Hephthalites, but on the way to Herat, he and his army were trapped by the Huns in the desert. Peroz I was killed and his army wiped out. After this victory the Hephthalites advanced to the city of Herat, throwing the empire into chaos. Eventually, a noble Persian from the old family of Karen, Zarmihr (or Sokhra), restored some degree of order. He raised Balash, one of Peroz I’s brothers, to the throne, although the Hunnic threat persisted until the reign of Khosrau I. Balash (484-488) was a mild and generous monarch, who made concessions to the Christians; however, he took no action against the empire’s enemies, particularly, the White Huns. Balash, after a reign of four years, was blinded and deposed (attributed to magnates), and his nephew Kavadh I became emperor.

Kavadh I (488–531) was an energetic and reformist ruler. Kavadh I gave his support to the communistic sect founded by Mazdak, son of Bamdad, who demanded that the rich should divide their wives and their wealth with the poor. His intention evidently was, by adopting the doctrine of the Mazdakites, to break the influence of the magnates and the growing aristocracy. These reforms led to his deposition and imprisonment in the “Castle of Oblivion” (Lethe) in Susa, and his younger brother Jamasp (Zamaspes) was raised to the throne in 496. Kavadh I, however, escaped in 498 and was given refuge by the White Hun king.

Djamasp (496-498) was installed on the Sassanid throne after Kavadh I was deposed by members of the nobility. Djamasp reduced taxes to relieve the peasants and the poor. Unlike Kavadh I, he supported the mainstream Mazdean religion. His reign soon ended when Kavadh I, at the head of a large army loaned by the Hephthalite king, returned to the empire’s capital. Djamasp stepped down from his position and restored the throne to his brother. Although Djamasp disappears from the records, it is widely believed that he was treated favorably at the court of his brother.

Second Golden Era (498–622 CE)

The second golden era began after the second reign of Kavadh I. With the support of the Hephtalites, Kavadh I launched a campaign against the Romans. In 502, he took Theodosiopolis (Erzurum) in Modern Turkey, but lost it soon afterwards. In 503 he took Amida (Diarbekr) on the Tigris. In 504, an invasion of Armenia by the western Huns from the Caucasus led to an armistice, the return of Amida to Roman control and a peace treaty in 506. In 521/2 Kavadh lost control of Lazica, whose rulers switched their allegiance to the Romans; an attempt by the Iberians in 524/5 to do likewise triggered a war between Rome and Persia. In 527 a Roman offensive against Nisibis was repulsed and Roman efforts to fortify positions near the frontier were thwarted. In 530, Kavadh sent an army under Firouz the Mirranes to attack the important Roman frontier city of Dara. The army was met by the Roman general Belisarius, and though superior in numbers, was defeated at the Battle of Dara. In the same year, a second Persian army under Mihr-Mihroe was defeated at Satala by Roman forces under Sittas and Dorotheus, but in 531 a Persian army accompanied by a Lakhmid contingent under al-Mundhir IV defeated Belisarius at the Battle of Callinicum, and in 532 an “eternal” peace was concluded.[17] Although he could not free himself from the yoke of the Ephthalites, Kavadh succeeded in restoring order in the interior and fought with general success against the Eastern Romans. He founded several cities, some of which were named after him and began to regulate the taxation and internal administration.

Kavadh I was succeeded by his son Khosrau I (531–579) also known as Anushirvan (“with the immortal soul”). One of the most celebrated Sassanid ruler, he is famous for reforming the aging Sassanid governing body by rationalizing taxation, based on a survey of landed possessions, which his father had begun. He also tried to increase the welfare and the revenues of his empire. Previous great feudal lords fielded their own military equipment, followers and retainers. Khosrau I developed a new force of dehkans or “knights” paid and equipped by the central government and the bureaucracy, tying the army and bureaucracy more closely to the central government than to local lords.

Although the Emperor Justinian I (527-565) had paid him a bribe of 440,000 pieces of gold to keep the peace, in 540 Khosrau I broke the “eternal peace” of 532 and invaded Syria, sacking the city of Antioch and extorting large sums of money from a number of other cities. Further successes followed: in 541 Lazica defected to the Persian side, and in 542 a major Byzantine offensive in Armenia was defeated at Anglon. A five-year truce agreed in 545 was interrupted in 547 when Lazica again switched sides and eventually expelled its Persian garrison with Byzantine help; the war resumed, but remained confined to Lazica, which was retained by the Byzantines when peace was concluded in 562.

In 565, Justinian I died and was succeeded by Justin II (565-578), who resolved to stop subsidies to Arab chieftains to restrain them from raiding Byzantine territory in Syria. A year earlier the Sassanid governor of Armenia built a fire temple at Dvin near modern Yerevan, and he put to death an influential member of the Mamikonian family, touching off a revolt which led to the massacre of the Persian governor and his guard in 571, while rebellion also broke out in Iberia]. Justin II took advantage of the Armenian revolt to stop his yearly payments to Khosrau I for the defense of the Caucasus passes. The Armenians were welcomed as allies, and an army was sent into Sassanid territory to besiege Nisibis in 573. However, dissension among the Byzantine generals not only led to the siege’s abandonment, but they in turn were besieged in the city of Dara, which was taken by the Persians. They then ravaged Syria, causing Justin II to agree to make annual payments in exchange for a five-year truce on the Mesopotamian front, although the war continued elsewhere. In 576 Khosrau I led his last campaign, an offensive into Anatolia which sacked Sebasteia and Melitene, but ended in disaster: defeated outside Melitene, the Persians suffered heavy losses as they fled across the Euphrates under Byzantine attack. Taking advantage of Persian disarray, the Byzantines raided deep into Khosrau’s territory, even mounting amphibious attacks across the Caspian Sea. Khosrau sued for peace, but he decided to continue the war after a victory by his general Tamkhosrau in Armenia in 577 and fighting resumed in Mesopotamia. The Armenian revolt came to an end with a general amnesty, which brought Armenia back into the Sassanid Empire.

Around 570 “Ma ‘d-Karib,” half-brother of the King of Yemen, requested Khosrau I’s intervention. Khosrau I sent a fleet and a small army under a commander called Vahriz to the area near present Aden, and they marched against the capital San’a’l, which was occupied. Saif, son of Mard-Karib, who had accompanied the expedition, became King sometime between 575 and 577. Thus the Sassanids were able to establish a base in south Arabia to control the sea trade with the east. Later the south Arabian kingdom renounced Sassanid overlordship, and another Persian expedition was sent in 598 that successfully annexed southern Arabia as a Sassanid province, which lasted until the time of troubles after Khosrau II.

Khosrau I’s reign witnessed the rise of the dihqans (literally, village lords), the petty landholding nobility who were the backbone of later Sassanid provincial administration and the tax collection system. Khosrau I was a great builder, embellishing his capital, founding new towns, and constructing new buildings. He rebuilt the canals and restocked the farms destroyed in the wars. He built strong fortifications at the passes and placed subject tribes in carefully chosen towns on the frontiers to act as guardians against invaders. He was tolerant of all religions, though he decreed that Zoroastrianism should be the official state religion, and was not unduly disturbed when one of his sons became a Christian.

After Khosrau I, Hormizd IV (579-590) took the throne. War with the Byzantines continued to rage intensely but inconclusively until the general Bahram Chobin, dismissed and humiliated by Hormizd, rose in revolt in 589. The following year Hormizd was overthrown by a palace coup and his son Khosrau II (590-628) placed on the throne, but this change of ruler failed to placate Bahram, who defeated Khosrau, forcing him to flee to Byzantine territory, and seized the throne for himself as Bahram VI. With the aid of troops provided by the Byzantine emperor Maurice (582-602), Khosrau II raised a new rebellion against Bahram, and the combined armies of Khosrau and the Byzantine generals Narses and John Mystacon won a decisive victory over Bahram at Ganzak (591), restoring Khosrau to power. In return for Maurice’s help, Khosrau was obliged to return all Byzantine territory occupied during the war and to hand over control of the western parts of Armenia and Iberia.

When Maurice was overthrown and killed by Phocas (602-610) in 602, Khosrau II used his benefactor’s murder as a pretext to begin a new invasion, which benefited from continuing civil war in the Byzantine Empire and met little effective resistance. Khosrau’s generals systematically subdued the heavily fortified frontier cities of Byzantine Mesopotamia and Armenia, laying the foundations for unprecedented expansion. The Persians overran Syria and captured Antioch in 611. In 613, outside Antioch, the Persian generals Shahrbaraz and Shahin decisively defeated a major counter-attack led in person by the Byzantine emperor Heraclius. After this, the Persian advance continued unchecked. Jerusalem fell in 614, Alexandria in 619 and the rest of Egypt by 621. The Sassanid dream of restoring the Achaemenid boundaries was close to completion. A blossoming of art, music and architecture accompanied this peak of expansion. The Byzantine Empire was on the verge of collapse while the borders of the Achaemenid Empire were close to being restored on all fronts.

Decline and Fall (622-651 CE)

Although hugely successful at first glance, Khosrau II’s campaign had overextended the Persian army and overtaxed the people. The Byzantine emperor Heraclius (610 – 641) drew on all his diminished and devastated empire’s remaining resources, reorganized his armies and mounted a remarkable counter-offensive. Between 622 and 627 he campaigned against the Persians in Anatolia and the Caucasus, winning a string of victories against Persian forces under Khosrau, Shahrbaraz, Shahin and Shahraplakan, sacking the great Zoroastrian temple at Ganzak and securing assistance from the Khazars and Western Turkic Khaganate. In 626 Slavic and Avar forces sieged Constantinople supported by a Persian army under Shahrbaraz on the far side of the Bosphorus. However, the Byzantinen fleet blocked attempts to ferry the Persians across and the siege ended in failure. In 627-628 Heraclius mounted a winter invasion of Mesopotamia and, despite the departure of his Khazar allies, defeated a Persian army commanded by Rhahzadh in the Battle of Nineveh. Marching down the Tigris, he devastated the country and sacked Khosrau’s palace of Dastagerd. He was prevented from attacking Ctesiphon by the destruction of the bridges on the Nahrawan Canal but conducted further raids before withdrawing up the Diyala river into north-western Iran.[18]

Heraclius’ victories, the devastation of the richest territories of the Sassanid Empire and the humiliating destruction of high-profile targets such as Ganzak and Dastagerd fatally undermined Khosrau’s prestige. Early in 628 he was overthrown and murdered by his son Kavadh II (628), who immediately brought an end to the war, agreeing to withdraw from all occupied territories. In 629 C.E. Heraclius restored the True Cross to Jerusalem in a majestic ceremony. Kavadh died within months and chaos and civil war followed. Over a period of four years and five successive kings, including a daughters of Khosrau II (Purandokht, queen 629-331), the Sassanid Empire weakened considerably as power passed into the hands of the generals. Purandokht renewed peace with Byzantium, lowered taxes but was unable to prevent the outbreak of civil war.[19] It would take several years for a strong king to emerge from a series of coups, and the Sassanids never had time to recover fully.

In the spring of 632, a grandson of Khosrau I who had lived in hiding, Yazdegerd III, ascended the throne. That year, the first raiders from the Arab tribes, newly united by Islam, arrived in Persian territory. Years of warfare had exhausted both the Byzantines and the Persians. Economic decline, heavy taxation, religious unrest, rigid social stratification, the increasing power of provincial landowners and a rapid turnover of ruler all further weakened the Sassanids as they faced the new threat.

The Sassanids never mounted a truly effective resistance to the pressure applied by the initial Arab armies. Yazdegerd, a boy at the mercy of his advisers, was incapable of uniting a vast country crumbling into small feudal kingdoms, despite the fact that the Byzantines, under similar pressure from the newly expansive Arabs, no longer threatened. The first encounter between Sassanids and Muslim Arabs was in the Battle of the Bridge in 634 and led to a Sassanid victory. The Arab threat, however, did not stop there, reappearing shortly from the disciplined armies of Khalid ibn Walid, once one of Muhammad’s chosen companions-in-arms and leader of the Arab army. Under the Caliph Umar, a Muslim army defeated a larger Persian force lead by general Rostam Farrokhzad at the plains of al-Qādisiyyah in 637 and besieged Ctesiphon. Ctesiphon fell after a prolonged siege. Yazdgerd fled eastward from Ctesiphon, leaving behind him most of the Empire’s vast treasury. The Arabs soon captured Ctesiphon, leaving the Sassanid government strapped for funds and acquiring a powerful financial resource for their own use. A number of Sassanid governors attempted to combine their forces to throw back the invaders, but the effort was crippled by lack of strong central authority, and the governors were defeated at the Battle of Nihawānd. Faced by the invaders, the empire, with its military command structure non-existent, its non-noble troop levies decimated, its financial resources effectively destroyed, and the Asawaran (Azatan) knightly caste destroyed piecemeal, was now utterly helpless.

Hearing of the defeat in Nihawānd, Yazdgerd along with most of Persian nobilities fled further inland to the eastern province of Khorasan. He was assassinated in late 651. The rest of the nobles settled in central Asia, where they contributed greatly in spreading Persian culture and language in those regions and the establishment of the first native Iranian Islamic dynasty, the Samanid dynasty, which sought to revive and resuscitate Sassanid traditions and culture after the invasion of Islam.

The abrupt fall of Sassanid Empire was completed in a period of five years, with most of its territory being absorbed into the Islamic caliphate. However, many Iranian cities resisted, including Rayy, Isfahan and Hamadan which were exterminated thrice by Islamic caliphates in order to suppress revolts.[20] The local population either willingly accepted Islam, or stayed as dhimmi subjects of the Muslim state and paid a poll tax (jizya). Invaders destroyed the Academy of Gundishapur and its library, burning piles of books. Most Sassanid records and literary works were destroyed. A few that escaped this fate were later translated into Arabic and later to Modern Persian. During the Islamic invasion many Iranian cities were destroyed or deserted, palaces and bridges were ruined and many magnificent imperial Persian gardens were burned to the ground.[21]

Government

Overview

The Sassanids established an empire roughly within the frontiers achieved by the Achaemenids, with the capital at Ctesiphon in the Khvarvaran province. In administering this empire, Sassanid rulers, took the title of Shāhanshāh (King of Kings), became the central overlords and also assumed guardianship of the sacred fire, the symbol of the national religion. This symbol is explicit on Sassanid coins where the reigning monarch, with his crown and regalia of office, appears on the obverse, backed by the sacred fire, the symbol of the national religion, on the coin’s reverse. Sassanid queens had the title of Banebshenan banebshen (the Queen of Queens).

On smaller scale the territory might also be ruled by a number of petty rulers from Sassanid royal family, known as Shahrdar overseen directly by Shahanshah. Considerable centralization, ambitious urban planning, agricultural development and technological improvements characterized Sassanid rule. Below the king a powerful bureaucracy carried out much of the affairs of government; the head of the bureaucracy and Vice-Chancellor, was the “Vuzorg (Bozorg) Farmadar“. Within this bureaucracy the Zoroastrian priesthood was immensely powerful. The head of the Magi priestly class, the Mobadan, along with the commander in chief, the Iran (Eran) Spahbod, the head of traders and merchants syndicate “Ho Tokhshan Bod” and minister of agriculture “Vastrioshansalar” who was also head of farmers, were below the emperor the most powerful men of the Sassanid state.[22]

In normal times the monarchical office was hereditary, but might be transmitted by the king to a younger son; in two instances queens held the supreme power. When no direct heir was available, the nobles and prelates chose a ruler, but their choice was restricted to members of the royal family.

The Sassanid nobility was a mixture of old Parthian clans, Persian aristocratic families, and noble families from subjected territories. Many new noble families had risen after the dissolution of the Parthian dynasty, while several of the once-dominant Seven Parthian clans remained of high importance. At the court of Ardashir I, the old Arsacid families of the House of Karen and the House of Suren, along with several Persian families, the Varazes and Andigans, held positions of great honor. Alongside these Iranian and non-Iranian noble families, the kings of Merv, Abarshahr, Carmania, Sakastan, Iberia, and Adiabene, who are mentioned as holding positions of honor amongst the nobles, appeared at the court of the Shahanshah. Indeed, the extensive domains of the Surens, Karens, and Varazes had become part of the original Sassanid state as semi-independent states. Thus, the noble families that attended at the court of the Sassanid empire continued to be ruling lines in their own right, although subordinate to the Shahanshah.

In general, Bozorgan from Persian families held the most powerful positions in the imperial administration, including governorships of border provinces (Marzban). Most of these positions were patrimonial, and many were passed down through a single family for generations. Those Marzbans of greatest seniority were permitted a silver throne, while Marzbans of the most strategic border provinces, such as the Caucasus province, were allowed a golden throne.[23] In military campaigns the regional Marzbans could be regarded as field marshals, while lesser spahbods could command a field army.[24]

Culturally, the Sassanids implemented a system of social stratification. This system was supported by Zoroastrianism, which was established as the state religion. Other religions appear to have been largely tolerated (although this claim is the subject of heated discussion. Sassanid emperors consciously sought to resuscitate Persian traditions and to obliterate Greek cultural influence.

Sassanid Army

The backbone of the Persian army (Spah) in the Sassanid era was composed of two types of heavy cavalry units: Clibanarii and Cataphracts. This cavalry force was composed of elite noblemen trained since youth for military service and was supported by light cavalry, infantry, and archers. Sassanid tactics centered on disrupting the enemy with archers, war elephants, and other troops, thus opening up gaps the cavalry forces could exploit.

Unlike their predecessors the Parthians, the Sassanids developed advanced siege engines. This development served the empire well in conflicts with Rome, in which success hinged upon the ability to seize cities and other fortified points; conversely, the Sassanids also developed a number of techniques for defending their own cities from attack. The Sassanid army was famous for its heavy cavalry, which was much like the preceding Parthian army, albeit only some of the Sassanid heavy cavalry were equipped with lances.

The Byzantine emperor Maurikios also emphasizes in his sixth century military treatise Strategikon that many of the Sassanid heavy cavalry did not carry spears, relying on their bows as their primary weapons.

The amount of money involved in maintaining a warrior of the knightly caste required a small estate, and the knightly caste received that from the throne, and in return, were the throne’s most notable defenders in time of war.

Relations with China

Like their predecessors the Parthians, the Sassanid Empire carried out active foreign relations with China, and ambassadors from Persia frequently traveled to China. Chinese documents report on thirteen Sassanid embassies to China. Commercially, land and sea trade with China was important to both the Sassanid and Chinese Empires. Large numbers of Sassanid coins have been found in southern China, confirming maritime trade.

On different occasions Sassanid kings sent their most talented Persian musicians and dancers to the Chinese imperial court at Luoyang during the Jin Dynasty (265-420) and Northern Wei dynasties and to Chang’an during the Sui and Tang dynasties. Both empires benefited from trade along the Silk Road, and shared a common interest in preserving and protecting that trade. They cooperated in guarding the trade routes through central Asia, and both built outposts in border areas to keep caravans safe from nomadic tribes and bandits.

Politically, we hear of several Sassanid and Chinese efforts in forging alliances against the common enemy who were the Hephthalites. Upon the rise of the nomadic Gokturk Empire in Inner Asia, we also see what looks like a collaboration between China and the Sassanid to defuse the Turkic advances. Documents from Mount Mogh also talk about the presence of a Chinese general in the service of the king of Sogdiana at the time of the Arab invasions.

Following the invasion of Iran by Muslim Arabs, Pirooz, son of Yazdegerd III, escaped along with a few Persian nobles and took refuge in the Chinese imperial court. Both Piroz and his son Narseh (Chinese neh-shie) were given high titles at the Chinese court. At least in two occasions, the last possibly in 670, Chinese troops were sent with Peroz in order to restore him to the Sassanid throne with mixed results, one possibly ending up in a short rule of Peroz in Sistan (Sakestan) from which we have a few remaining numismatic evidences. Narseh later attained the position of commander of the Chinese imperial guards and his descendants lived in China as respected princes.

Expansion to India

After the Sassanids had secured Iran and its neighboring regions under Ardashir I, the second emperor, Shapur I (240–270), extended his authority eastwards into what is today Pakistan and northwestern India. The previously autonomous Kushans were obliged to accept his suzerainty. Although the Kushan empire declined at the end of the third century, to be replaced by the northern Indian Gupta Empire in the fourth century, it is clear that Sassanid influence remained relevant in India’s northwest throughout this period.

Persia and northwestern India engaged in cultural as well as political intercourse during this period, as certain Sassanid practices spread into the Kushan territories. In particular, the Kushan’s were influenced by the Sassanid conception of kingship, which spread through the trade of Sassanid silverware and textiles depicting emperors hunting or dispensing justice.

This cultural interchange did not, however, spread Sassanid religious practices or attitudes to the Kushans. While the Sassanids always adhered to a stated policy of religious proselytization, and sporadically engaged in persecution or forced conversion of minority religions, the Kushans preferred to adopt a policy of religious tolerance.

Lower-level cultural interchanges also took place between India and Persia during this period. For example, Persians imported chess from India and changed the game’s name from chaturanga to chatrang. In exchange, Persians introduced Backgammon to India.

During Khosrau I’s reign many books were brought from India and translated into Pahlavi, the language of the Sassanid Empire. Some of these later found their way into the literature of the Islamic world. A notable example of this was the translation of the Indian Panchatantra by one of Khosrau’s ministers, Burzoe; this translation, known as the Kelileh va Demneh, later made its way into Arabia and Europe.[25] The details of Burzoe’s legendary journey to India and his daring acquirement of Panchatantra is written in full details in Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh[26].

Iranian society under the Sassanids

Overview

In the region at the time, only the Byzantines could rival Sassanid society and civilization. The amount of scientific and intellectual exchange between the two empires is witness to the competition and cooperation of these cradles of civilization.

The most striking difference between Parthian and Sassanid society was renewed emphasis on charismatic and centralized government. In Sassanid theory, the ideal society was one which could maintain stability and justice and the necessary instrument for this was a strong monarch.[27] Sassanid society was immensely complex, with separate systems of social organization governing numerous different groups within the empire.[28] Historians believe that society was divided into four classes: Priests (Atorbanan in Persian), Warriors (Arteshtaran in Persian), Secretaries (Dabiran in Persian: دبيران), and Commoners (Vasteryoshan-Hootkheshan in Persian). At the center of the Sassanid caste system was the Shahanshah, ruling over all the nobles.[29] The royal princes, petty rulers, great landlords, and priests together constituted a privileged stratum, and were identified as Bozorgan, or nobles. This social system appears to have been fairly rigid. The Sassanid caste system outlived the empire, continuing in the early Islamic period.[29]

Membership in a class was based on birth, although it was possible for an exceptional individual to move to another class on the basis of merit. The function of the king was to ensure that each class remained within its proper boundaries, so that the strong did not oppress the weak, nor the weak the strong. To maintain this social equilibrium was the essence of royal justice, and its effective functioning depended on the glorification of the monarchy above all other classes.[27]

On a lower level, Sassanid society was divided into Azatan (Azadan), (freemen), who jealously guarded their status as descendants of ancient Aryan conquerors, and the mass of originally non-Aryan peasantry. The Azatan formed a large low-aristocracy of low-level administrators, mostly living on small estates. The Azatan provided the cavalry backbone of the army.[28]

Art, Science, and Literature

The Sassanid kings were enlightened patrons of letters and philosophy. Khosrau I had the works of Plato and Aristotle translated into Pahlavi taught at Gundishapur, and even read them himself. During his reign many historical annals were compiled, of which the sole survivor is the “Karnamak-i Artaxshir-i Papakan” (Deeds of Ardashir), a mixture of history and romance that served as the basis of the Iranian national epic, the “Shahnama.” When Justinian I closed the schools of Athens, seven of their professors fled to Persia and found refuge at Khosrau’s court. In time they grew homesick, and in his treaty of 533 with Justinian, the Sassanid king stipulated that the Greek sages should be allowed to return and be free from persecution.

Under Khosrau I the college of Gundishapur, which had been founded in the fourth century, became “the greatest intellectual center of the time,” drawing students and teachers from every quarter of the world. Nestorian Christians were received there, and brought Syriac translations of Greek works in medicine and philosophy. Neoplatonists, too, came to Gundishapur, where they planted the seeds of Sufi mysticism; the medical lore of India, Persia, Syria, and Greece mingled there to produce a flourishing school of therapy.

Artistically, the Sassanid period witnessed some of the highest achievements of Persian civilization. Much of what later became known as Muslim culture, including architecture and writing, was originally drawn from Persian culture. At its peak the Sassanid Empire stretched from Syria to northwest India, but its influence was felt far beyond these political boundaries. Sassanid motifs found their way into the art of Central Asia and China, the Byzantine Empire, and even Merovingian France. Islamic art however, was the true heir to Sassanid art, whose concepts it was to assimilate while, at the same time instilling fresh life and renewed vigor into it.

Sassanid carvings at Taq-e Bostan and Naqsh-e Rustam were colored; so were many features of the palaces; but only traces of such painting remain. The literature, however, makes it clear that the art of painting flourished in Sasanian times; the prophet Mani is reported to have founded a school of painting; Firdowsi speaks of Persian magnates adorning their mansions with pictures of Iranian heroes; and the poet al-Buhturidescribes the murals in the palace at Ctesiphon. When a Sasanian king died, the best painter of the time was called upon to make a portrait of him for a collection kept in the royal treasury.

Painting, sculpture, pottery, and other forms of decoration shared their designs with Sasanian textile art. Silks, embroideries, brocades, damasks, tapestries, chair covers, canopies, tents, and rugs were woven with patience and masterly skill, and were dyed in warm tints of yellow, blue, and green. Every Persian but the peasant and the priest aspired to dress above his class; presents often took the form of sumptuous garments; and great colorful carpets had been an appendage of wealth in the East since Assyrian days. The two dozen Sasanian textiles that have survived are among the most highly valued fabrics in existence. Even in their own day, Sasanian textiles were admired and imitated from Egypt to the Far East; and during the Middle Ages they were favored for clothing the relics of Christian saints. When Heraclius captured the palace of Khosru Parvez at Dastagird, delicate embroideries and an immense rug were among his most precious spoils. Famous was the “Winter Carpet,” also known as “Khosro’s Spring” (Spring Season Carpet) of Khosru Anushirvan, designed to make him forget winter in its spring and summer scenes: flowers and fruits made of inwoven rubies and diamonds grew, in this carpet, beside walks of silver and brooks of pearls traced on a ground of gold. Harun al-Rashid prided himself on a spacious Sasanian rug thickly studded with jewelry. Persians wrote love poems about their rugs.

Studies on Sassanid remains show over 100 types of crowns being worn by Sassanid kings. The various Sassanid crowns demonstrate the cultural, economic, social, and historical situation in each period. The crowns also show the character traits of each king in this era. Different symbols and signs on the crowns, the moon, stars, eagle, and palm, each illustrate the wearer’s religious faith and beliefs.

The Sassanid Dynasty, like the Achaemenid, originated in the province of Persis (Fars). The Sassanids saw themselves as successors of the Achaemenids, after the Hellenistic and Parthian interlude, and believed that it was their destiny to restore the greatness of Persia.

In reviving the glories of the Achaemenid past, the Sassanids were no mere imitators. The art of this period reveals an astonishing virility, in certain respects anticipating key features of Islamic art. Sassanid art combined elements of traditional Persian art with Hellenistic elements and influences. The conquest of Persia by Alexander the Great had inaugurated the spread of Hellenistic art into Western Asia. Though the East accepted the outward form of this art, it never really assimilated its spirit. Already in the Parthian period, Hellenistic art was being interpreted freely by the peoples of the Near East. Throughout the Sassanid period there was reaction against it. Sassanid art revived forms and traditions native to Persia, and in the Islamic period, these reached the shores of the Mediterranean.[30]

Surviving palaces illustrate the splendor in which the Sassanid monarchs lived. Examples include palaces at Firouzabad and Bishapur in Fars and the capital city of Ctesiphon in Khvarvaran province, Iraq. In addition to local traditions, Parthian architecture influenced Sassanid architectural characteristics such as the barrel-vaulted arches, introduced in the Parthian period. During the Sassanid period, these reached massive proportions, particularly at Ctesiphon. There, the arch of the great vaulted hall, attributed to the reign of Shapur I (241–272), has a span of more than 80 feet (24 m) and reaches a height of 118 feet (36 m). This magnificent structure fascinated architects in the centuries that followed and has been considered one of the most important examples of Persian architecture. Many of the palaces contain an inner audience hall consisting, as at Firuzabad, of a chamber surmounted by a dome. The Persians solved the problem of constructing a circular dome on a square building by employing squinches, or arches built across each corner of the square, thereby converting it into an octagon on which it is simple to place the dome. The dome chamber in the palace of Firouzabad is the earliest surviving example of the use of the squinch, suggesting that this architectural technique was probably invented in Persia.

The unique characteristic of Sassanid architecture was its distinctive use of space. The Sassanid architect conceived his building in terms of masses and surfaces; hence the use of massive walls of brick decorated with molded or carved stucco. Stucco wall decorations appear at Bishapur, but better examples are preserved from Chal Tarkhan near Rayy (late Sassanid or early Islamic in date), and from Ctesiphon and Kish in Mesopotamia. The panels show animal figures set in roundels, human busts, and geometric and floral motifs.

At Bishapur some of the floors were decorated with mosaics showing scenes of banqueting. The Roman influence here is clear, and the mosaics may have been laid by Roman prisoners. Buildings were decorated with wall paintings. Particularly fine examples have been found on Mount Khajeh in Sistan (Baluchistan).

Industry and Trade

Persian industry under the Sassanids developed from domestic to urban forms. Guilds were numerous, and some towns had a revolutionary proletariat. Silk weaving was introduced from China; Sassanid silks were sought after everywhere, and served as models for the textile art in Byzantium, China, and Japan. Chinese merchants came to thriving Iranian ports such as Siraf to sell raw silk and buy rugs, jewels, rouge; Armenians, Syrians, and Jews connected Persia, Byzantium, and Rome in slow exchange. Good roads and bridges, well patrolled, enabled state post and merchant caravans to link Ctesiphon with all provinces; and harbors were built in the Persian Gulf to quicken trade with India. Sassanid merchants ranged far and wide and gradually ousted Romans from lucrative Indian Ocean trade routes.[31] The recent Archeological discovery has shown an interesting fact that Sassanids used special labels (commercial labels) on goods as a way of promoting their brands and distinguish between different qualities.

Khosrau I further extended the already vast trade network. The Sassanid state now tended toward monopolistic control of trade, with luxury goods assuming a far greater role in the trade than heretofore, and the great activity in building of ports, caravanserais, bridges, and the like was linked to trade and urbanization. The Persians dominated international trade, both in the Indian Ocean and in Central Asia and South Russia in the time of Khosrau, although competition with the Byzantines was at times intense. Sassanian settlements in Oman and Yemen testify to the importance of trade with India, but the silk trade with China was mainly in the hands of Sassanid vassals and the Iranian people, the Sogdians.

The main exports of the Sassanids were silk, woolen and golden textile, carpets and rugs, skin, leather and pearls from the Persian Gulf. Also there were goods in transit from China (paper, silk) and India (spices) which Sassanid customs imposed taxes upon and which were re-exported from the Empire to Europe.[32]

It was also a time of increased metallurgical production, so Iran earned a reputation as the “armory of Asia.” Most of the Sassanid mining centers were at the fringes of the Empire, in Armenia, the Caucasus and above all Transoxania. The extraordinary mineral wealth of the Pamir Mountains on the eastern horizon of the Sassanid Empire led to a legend among the Tajiks, an Iranian people living there, which is still told today.

“It said when God was creating the world, he tripped over Pamirs, dropping his jar of minerals which spread across the region.”[31]

Religion

The religion of the Sassanid state was Zoroastrianism, but Sassanid Zoroastrianism had clear distinctions from the practices laid out in the Avesta, the holy books of Zoroastrianism, first written in the Avesta language, and later in Pahlavi. Sassanid Zoroastrian clergy modified the religion in a way to serve themselves, causing substantial religious uneasiness. Sassanid religious policies contributed to the flourishing of numerous religious reform movements, the most important of these being the Mani and Mazdak religions. Alongside Zoroastrianism other religions, primarily Judaism, Christianity and Buddhism existed in Sassanid society, and were largely free to practice and preach their beliefs. A very large Jewish community flourished under Sassanid rule, with thriving centers at Isfahan, Babylon and Khorasan, and with its own semiautonomous Exilarchate leadership based in Mesopotamia. This community would, in fact, continue to flourish until the advent of Zionism.[24] Jewish communities suffered only occasional persecution. They enjoyed a relative freedom of religion, and were granted privileges denied to other religious minorities.[33] Shapur I (Shabur Malka in Aramaic) was a particular friend to the Jews. His friendship with Shmuel produced many advantages for the Jewish community.[34] Shapur II, whose mother was Jewish, had a similar friendship with a Babylonian rabbi named Raba. Raba’s friendship with Shapur II enabled him to secure a relaxation of the oppressive laws enacted against the Jews in the Persian Empire. In the eastern portion of the empire, various Buddhist places of worship, notably in Bamiyan were active as Buddhism gradually became more popular in that region.

Christians in Iran at this time belonged mainly to the Nestorian and Jacobite branches of Christianity, also known as respectively the Assyrian Church of the East and the Syriac Orthodox Church. Although these churches originally maintained ties with the Christian churches in the Roman Empire, they were indeed quite different from them. One of the most important reasons for this, is that the Church language of the Nestorian and Jacobite churches was the Aramaic language, which is also the language spoken by the Jews in Judea and Galilee at the time of Jesus. This language was not used by the vast majority of the Christians in the Roman Empire, who mainly spoke Latin, Koine Greek, or Coptic.

Another reason that the churches within the Persian Empire did not maintain such close ties with their counterparts in the Roman Empire, was the continuous rivalry between these two great empires. Christians in Persia were often falsely accused of sympathizing with the Romans, especially when the Roman emperor Theodosius I declared Christianity the state religion of the Roman Empire.

It was after the Council of Ephesus in 431 that the vast majority of Christians in Persia broke their ties with the churches in the Roman Empire. At this council, Nestorius, a theologian of Cilician/Kilikian origin and the patriarch of Constantinople, taught a different view of the Christology that was rejected and regarded as heretical by the majority of Greek, Roman and Coptic Christians. Nestorius refused to call Mary (mother of Jesus)Mary the mother of Jesus Christ “Theotokos” meaning literally “Mother of God”. The Assyrian Church refused to condemn Nestorius’ teachings. Nestorius, however, who was condemned by the majority of Christians, was deposed as patriarch and fled into the Sassanid Empire, where he was allowed to settle. He and his followers were welcomed into the Assyrian Church in Mesopotamia. Several Persian emperors also used this opportunity to strengthen Nestorius’ position within the Assyrian Church (which made up the vast majority of the Christians in the Persian Empire) by eliminating the most important pro-catholic clergymen in Persia and making sure that their places were taken by Nestorians. This was to assure that the only loyalty these Christians would have would be to the Persian Empire.

Legacy and Importance

The great strength of Sassanid culture was that it openly drew on, and inter-acted with, the cultures with which it enjoyed contact, creating a synthesis.

In Europe

The character of the Roman army was affected by the methods of Persian warfare. In a modified form, the Roman Imperial autocracy imitated the royal ceremonies of the Sassanid court. These, in turn, had an influence on the ceremonial traditions of the courts of modern Europe. The origin of the formalities of European diplomacy is attributed to the diplomatic relations between the Persian and Roman Empires.[35]

Through the late Roman Empire’s adoption of Cataphract cavalry, the principles of the European knighthood (heavily armored cavalry) of the Middle Ages can be traced to the Sassanid knightly caste with whom it also shares a number of similarities.

In Jewish History

After the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 C.E. the Jews of the Sassanid Empire played a leading role in the development of Jewish thought, including the making of the Babylonian Talmud, when the great Talmudic Academies in Babylonia flourished during the Rabbinic era of the Amoraim.

In India

Following the collapse of the Sassanid Empire, when Islam supplanted Zoroastrianism, Zoroastrians became a persecuted minority. A number of them chose to emigrate. According to the Qissa-i Sanjan, which tells of the emigration of Zoroastrians from Iran to India, one group of those refugees landed in what is now Gujarat, India, where they were allowed greater freedom to observe their old customs and to preserve their faith. The descendants of those Zoroastrians, now known as the Parsis, would play a significant role in the development of India. Today there are around 70,000 Parsis in India.

The Parsis still use a variant of the religious calendar instituted under the Sassanids. That calendar still marks the number of years since the accession of Yazdegerd III, just as it did in 632.

Islam

Zarinkoob even goes to the extent of claiming that much of what later became known as Islamic culture, architecture, writing and other skills was borrowed mainly from the Sassanid Persians and propagated throughout the broader Muslim world, although this assertion has not been corroborated by other scholars.[36] The Abbasids were especially influenced by the Sassanid legacy, adopting their court etiquette as well as their paid military, in which Persians “played a major role.” The Caliphs adopted the “Persian-inspired title, Shadow of God on Earth” and required to bow and kiss the ground before them.[37]

Appendix

Notes

- Richard Nelson Frye, 2005. “The Sassanians.” 461-480. in Alan Bowman, Averil Cameron, and Peter Garnsey, (eds.) The Cambridge Ancient History – XII – The Crisis of Empire. (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press), 461

- Frye, 2005, 464-465.

- Abdolhossein Zarinkoob. 1999. Ruzgaran: tarikh-i Iran az aghz ta saqut saltnat Pahlvi. (Tehrān, IR: Mahārat), 194–198. (in Arabic)

- Frye, 2005, 465-466.

- Frye, 2005, 466-467.

- Richard Nelson Frye, 1993. “The Political History of Iran under the Sassanians.” 116-180 in William Bayne Fisher, et al. (eds.) 1993. The Cambridge History of Iran. (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press), 124.

- Frye, 1993, 125.

- Frye, 1993, 126.

- Zarinkoob, 1999, 197.

- Zarinkoob, 1999, 199.

- Zarinkoob, 1999, 200.

- Zarinkoob, 1999, 206.

- Frye, 1993, 145.

- Zarinkoob, 1999, 218.

- Zarinkoob, 1999, 217.

- Zarinkoob, 1999, 219.

- Zarinkoob. 1999. page 229.

- John Haldon. 1997. Byzantium in the Seventh Century: the Transformation of a Culture. (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press), 46.

- Purandokht. Nation Master. Retrieved September 12, 2008.

- Zarinkoob, 1999, 305–317.

- Zarinkoob, 1999, 307.

- Sarfaraz and Firuzmandi, 1996, 344.

- David Nicolle. 1996. Sassanian Armies: the Iranian Empire Early 3rd to Mid-7th Centuries AD. (Stockport, UK: Montvert), 10.

- Nicolle, 1996, 14.

- Zarinkoob, 1999, 239.

- The Epic of Shahnameh Ferdowsi. Retrieved January 22, 2009.

- Elton L. Daniel. 2001. The History of Iran. (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press), 57.

- Nicolle, 1996, 11.

- Zarinkoob, 1999, 201.

- K. Kianush, 1999, Iransaga: The art of Sassanians. Art Arena. Retrieved September 12, 2008.

- Nicolle, 1996, 6.

- Sarfaraz and Firuzmandi, 1996, 353.

- Zarinkoob, 1999, 272.

- Zarinkoob, 1999, 207.

- J.B.(John Bagnell) Bury. 1923. History Of The Later Roman Empire. (London, UK: Macmillan), 109.

- Zarinkoob, 1999, 305.

- John L. Esposito. 1998. Islam: The Straight Path. (New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 51.

References

- Aurelius Victor. Liber de Caesaribus.The Latin Library. Retrieved September 12, 2008.

- Bury, J.B. (John Bagnell) 1923. History Of The Later Roman Empire. London, UK: Macmillan. online, History Of The Later Roman Empire. Univ. of Chicago. Retrieved January 22, 2009.

- Daniel, Elton L. 2001. The History of Iran. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

- Esposito, John L. 1998. Islam: The Straight Path. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Frye, Richard Nelson. 1993. “The Political History of Iran under the Sassanians.” 116-180 in William Bayne Fisher, Ilya Gershevitch, Ehsan Yarshater, R. N. Frye, J. A. Boyle, Peter Jackson, Laurence Lockhart, Peter Avery, Gavin Hambly and Charles Melville, eds. 1993. The Cambridge History of Iran. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Frye, Richard Nelson. 2005. “The Sassanians.” 461-480 in Alan Bowman, Averil Cameron, and Peter Garnsey, eds. The Cambridge Ancient History – XII – The Crisis of Empire. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Haldon, John. 1997. Byzantium in the Seventh Century: the Transformation of a Culture. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Herodian. 1961. Herodian of Antioch’s History of the Roman Empire. Book VI. Translated by Edward C. Echols. Berkeley, CA: California University Press. Retrieved September 12, 2008.

- Nicolle, David. 1996. Sassanian Armies: the Iranian Empire Early 3rd to Mid-7th Centuries AD. Stockport, UK: Montvert.

- Sarfaraz, Ali Akbar, and Bahman Firuzmandi. 1996. Mad, Hakhamanishi, Ashkani, Sasani. Tihrān, IR: Intishārāt-i ʻAfāf.Sibylline Oracles. 1899. Book XIII. sacred-texts.com. Translated by Milton S. Terry. New York, NY: Eaton & Mains ; Cincinnati, OH: Curts & Jennings. Retrieved September 12, 2008.

- Zarinkoob, Abdolhossein. 1999. Ruzgaran: tarikh-i Iran az aghz ta saqut saltnat Pahlvi. Tehrān, IR: Mahārat.

Originally published by New World Encyclopedia, 11.02.2019, under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.