By the close of the nineteenth century, prosthetics had moved from artisanal oddities to standardized commodities. They embodied the marriage of medicine and industry, of necessity and invention.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

War, Amputation, and the Surge in Demand

The nineteenth century was an age of amputation. War, industrial accident, and disease conspired to produce a scale of bodily loss unseen in earlier eras. The Napoleonic campaigns of the early century left thousands of men dependent on artificial limbs, while the American Civil War alone created more than thirty thousand amputees in the Union Army.1 Such numbers generated not only a human crisis but an institutional one. Governments found themselves compelled to support the production of prosthetic limbs, both as a duty to disabled veterans and as a strategy of reintegration into labor and citizenship.

Unlike earlier centuries, when prosthetics remained artisanal curiosities or individual commissions, the nineteenth century witnessed the rise of a systematic industry. Prosthetic makers received patents, founded workshops, and advertised their devices in catalogues. The missing limb was no longer merely a personal tragedy but a problem of public health and state responsibility.

Wooden Pegs and the “Palmer Leg”

The crude wooden peg leg persisted into the nineteenth century, but it was joined by new inventions that promised mobility with greater naturalism. In 1846, Benjamin Franklin Palmer patented what came to be called the “Palmer Leg.” This device incorporated an articulated knee, concealed steel tendons, and a spring foot that imitated the roll of a natural gait.2 Unlike the stiff peg, it allowed smoother walking and less conspicuous movement.

The United States government recognized its value. Following the Civil War, Congress authorized mass purchases of Palmer Legs for distribution to veterans. For the first time, a prosthetic became both a commodity and a standard issue, transforming the relationship between technology and the state.

Other inventors built on Palmer’s work. In Britain and continental Europe, rival designs competed for recognition, many advertised with testimonials of men who returned to work or even military drill while wearing them. These promotional stories, whether exaggerated or genuine, helped cast prosthetics not simply as replacements but as technologies of restoration, returning the body to its rightful place in society.

Prosthetic Arms: Hooks, Hands, and Labor

Arms presented greater challenges. Walking could be imitated by hinges and springs; grasping required dexterity. For laborers, the solution was pragmatic. Many opted for prosthetic arms terminating in iron hooks or clamps. These were not designed to look human but to perform work: to hold a hammer, lift a saw, or grip a plow. Function took precedence over appearance.

For those of higher means or gentility, artisans developed prosthetic hands fashioned of carved wood, covered in leather, and sometimes fitted with gloves. Certain models incorporated simple springs that allowed fingers to flex when pressed against objects.3 They were not truly functional but gave the illusion of completeness, masking absence in a society sensitive to deformity.

Some inventors experimented with hybrid models, combining utility with cosmetic covering. A hand might be fitted with detachable parts: one glove for social appearances, another tool attachment for labor. These transitional designs reveal how prosthetics were not only medical devices but cultural compromises, negotiating between dignity and productivity.

Materials and Mechanisms

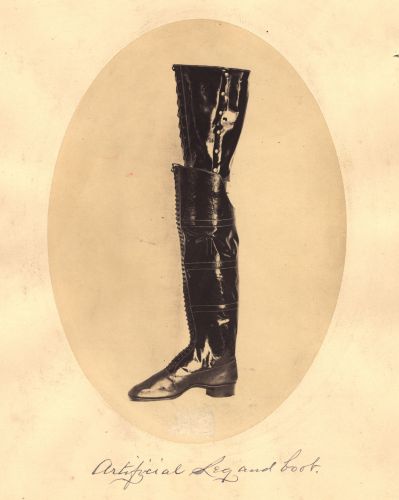

The evolution of materials shaped the evolution of design. Wood remained central, chosen for its lightness and workability. Leather provided flexible harnesses to secure limbs to the body. Metals, particularly iron and steel, were used for joints and supports, lending strength at critical points of articulation.

The introduction of vulcanized rubber in the 1840s added new possibilities. Rubber pads were used for feet and finger tips, softening the contact between prosthetic and ground, or between hand and object. These innovations produced limbs that were both more durable and more lifelike, bridging the divide between appearance and function.

By the later nineteenth century, standardized production techniques meant that parts could be replaced more easily.4 Instead of commissioning an entirely new leg, a veteran might have only a worn spring or strap replaced. This industrial approach to prosthetics paralleled other consumer goods, embedding artificial limbs in the same culture of repair and interchangeability that defined modern machinery.

At the same time, these new materials altered how wearers experienced their bodies. Rubber pads changed not only how a limb looked but how it felt, cushioning the jolt of movement. Steel joints allowed smoother walking but also increased weight. The prosthetic body became a negotiation between sensation and technology, forcing individuals to adapt daily life to the peculiarities of invention.

Aesthetics versus Utility

A social tension pervaded nineteenth-century prosthetics: the divide between aesthetic concealment and functional efficiency. Wealthier amputees commissioned limbs that imitated the look of flesh, complete with gloves, stockings, or boots to disguise their artifice. The goal was to restore the image of wholeness, to avoid the stigma of disability in polite society.

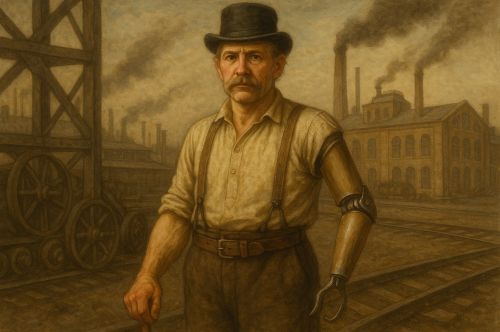

Working men, by contrast, often valued limbs that made no pretense of naturalism. A wooden leg that could bear weight or a hook that could grip a tool was of greater worth than cosmetic likeness. In this way, prosthetics mirrored the class structure of the century: luxury for the affluent, labor utility for the worker.

Prosthetics and the Body Politic

Prosthetics in the nineteenth century were not merely medical devices. They were also political symbols. Governments that provided limbs to veterans affirmed their loyalty to those who had sacrificed. By restoring soldiers to mobility, states restored them to the symbolic body of the nation. In the industrial workplace, prosthetics allowed men injured in factories or mines to return to labor, reinforcing ideals of productivity and masculine self-reliance.5

The prosthetic limb thus functioned as a bridge between body and society, transforming absence into presence. It did not erase disability, but it allowed it to be managed, rendered less disruptive to the demands of citizenship and work.

Conclusion: Mechanized Humanity

By the close of the nineteenth century, prosthetics had moved from artisanal oddities to standardized commodities. They embodied the marriage of medicine and industry, of necessity and invention. Wooden pegs gave way to articulated knees; hooks and clamps sat beside cosmetic hands; rubber, steel, and leather combined in ever more sophisticated forms.

In this hybrid of flesh and mechanism, the century revealed its character. It was an age that sought to overcome loss through technology, to convert the broken body into a productive one. The prosthetic was not only a tool for the individual but a symbol of society’s determination to bind its wounded back into the machinery of modern life.

Appendix

Notes

- Guy R. Hasegawa, Mending Broken Soldiers: The Union and Confederate Programs to Supply Artificial Limbs (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2012), 5–7.

- David Serlin, Replaceable You: Engineering the Body in Postwar America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004), 18–19.

- Katherine Ott, The Sum of Its Parts: An Introduction to Modern Prosthetics (New York: Routledge, 2002), 42–45.

- Julie Anderson, War, Disability and Rehabilitation in Britain: Soul of a Nation (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2011), 13–15.

- James Howland, A History of Orthopedics (Atlanta: Litfire Publishing, 2018), 22–24.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Julie. War, Disability and Rehabilitation in Britain: Soul of a Nation. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2011.

- Hasegawa, Guy R. Mending Broken Soldiers: The Union and Confederate Programs to Supply Artificial Limbs. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2012.

- Howland, James. A History of Orthopedics. Atlanta: Litfire Publishing, 2018.

- Ott, Katherine. The Sum of Its Parts: An Introduction to Modern Prosthetics. New York: Routledge, 2002.

- Serlin, David. Replaceable You: Engineering the Body in Postwar America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004.

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.19.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.