Individual penance was simply not enough, some collective and common forms were called on.

By Dr. Jussi Hanska

Professor of History

Tampere University

Introduction

Despite all the spiritual and practical precautions taken, disasters could still not be avoided. What, then was done in the midst of disaster; how did people try to cope with the situation? More important still, how did they try to stop it? Studying human reactions and behaviour during catastrophes is difficult, not in the least because of the hectic nature of the phenomena. Some catastrophes, such as earthquakes, happened so quickly that there was hardly time to do anything, at least anything planned and rational. In the case of long-term disasters such as droughts, it is difficult to decide whether we are actually dealing with post-disaster activities or with measures taken during the catastrophe. The best results are achieved with the sources that discuss longer lasting disasters, such as famines and floods. In the evaluation of these sources it is important to distinguish between individual and community responses to disasters.

It has been emphasised that common expressions of penance were the most important spiritual means of fighting natural disasters. Individual penance was simply not enough, some collective and common forms were called on to impress and placate God with the continuity of the prayers and chants and the numbers of participants. Jean Delumeau has rightly labelled catastrophe liturgy as quantitative religion.95 If we take a look into these collective religious responses in front of natural disasters, we find that there were basically three important spiritual means of dealing with the catastrophes: sermons, processions, and votive Masses.

With these instruments the community turned towards God and the saints to seek protection in the moment of danger. Sometimes it is difficult to distinguish between these measures, since processions were actually part of some Masses, and sermons usually took place after Mass, and occasionally also in connection with processions. There are numerous examples of sermons held at some stage of a procession. Hence, bishop Federico Pisano Visconti addressed his fellow citizens in his second Rogation Day sermon as follows:

‘Yesterday we preached on the first loaf, that is, the faith. Today we have to speak shortly of the second, that is hope. The reason for this is that we are somewhat tired having walked the long way to be here at St. Peter the Apostle ad Gradum. Nevertheless, let us pray to blessed Peter to whom God gave specific grace of preaching, so that he might intercede on behalf of us with our Lord Jesus Christ.’96

From this passage it is obvious that Federico was preaching in a station church where the procession ended. Similar passages can be found in other sermons. Thus we have established that sermons, masses and processions were all part of the liturgical setting of a catastrophe situation. They were all parts of a greater whole that could be called catastrophe liturgy. Nevertheless, for the sake of clarity all these measures are treated in separate chapters.

Processions

Processions are among the most fascinating phenomena in medieval history, for they provide us with a glimpse of medieval popular religion as it really was. Masses and sermons were essentially clerical matters, although they are interesting and can be informative about public opinions and practices. Processions, though led by the clergy, were open to anyone. In fact, the presence of the public was required. Without participation of the populace there could not have been a procession. Thus, ordinary Christians were encouraged to express their religious feelings, and to actively participate in a religious ceremony. In sermons and masses their function was to participate only passively.

In the previous chapter we have seen that processions were organised on a yearly basis to obtain protection from God and, most of all, to secure the growing of crops. In addition to Rogation Days, processions and litanies were performed in cases of natural disasters in line with the examples set by Mamertus and Gregory the Great.97

Let us now look at some of the other early descriptions of these processiones causa necessitatis. In his book about miracles in medieval France, Pierre-André Segal has included a description of an early twelfth-century procession. Sometime in the 1120’s an epidemic ravished the area of Soissons. Seeing that the epidemic was taking a very nasty turn, and remembering how Gregory the Great had managed to save the inhabitants of Rome from the plague, the bishop of Soissons decided to organise a procession. He sent messengers to the nearby abbey of Saint-Médard, where the relics of saint Gregory were stored.

These and other relics from the nearby churches were brought to the cathedral, which served as a starting place of the procession. People were exhorted to do penance through fasting, praying and almsgiving. Then the bishop celebrated mass and held a sermon, after which the procession was ready to get started. The participants were required to walk barefooted. The procession circulated the town, forming a sphere of protection, and then moved on to the abbey. If we can believe the chronicler the processions indeed had positive effects. Several of the people that had been affected by the epidemic were miraculously cured, and after the procession, no one died in Soissons while the epidemic lasted.98

Catastrophe processions have not only left traces in medieval chronicles, they can also be found in contemporary liturgical Sources. Studying these, one gets a clearer picture of the frequency of such processions. Terence Bailey has analysed the distribution of rogation antiphons in twenty of the oldest French, Aquitanian, German, and Italian gradual manuscripts as well as in the concordances of Visigothic, Milanese, and Old Roman books. These sources are dated between the eighth and the twelfth centuries. Nearly all of these contain special antiphons for asking for rain or for delivery from floods or other natural disasters. The sole exception is found in the oldest of these manuscripts, the Mont-Blandin (near Ghent) Gradual.99

On the basis of his analysis, we may conclude that from the ninth century on processions with special prayers against drought, floods, and other natural disasters, were so common that it was customary to add special antiphons for such occasions to graduals. Indeed, Pierre-André Sigal claims that by the early eleventh century the custom of organising catastrophe processions with relics had become well established in the whole of western Christianity.100

During the High Middle Ages, the flow of sources describing catastrophe processions is continuous. Interesting examples are the processions organised in Paris in response to the flooding of the Seine and other catastrophes. In 1129–1130, there was an epidemic disease that killed masses of Parisians. The epidemic of 1129–1130 was ended with a procession and the intervention of saint Geneviève. Thereafter it became customary in Paris to carry her relics in procession from the monastery where they were normally kept across the river to the Notre-Dame.101

This was not the last of saint Geneviève’s successive interventions. We know that her relics were again carried processionaliter in connection with the serious floods of 1206. After the relics had been brought into the Notre-Dame, and obligatory celebrations had been held the flood ceased. Then the relics of saint Geneviève were carried back to the abbey. Half an hour after the procession had crossed the bridge called le Petit-Pont, it collapsed into the river. Miraculously no one was on the bridge when it collapsed. This was perceived as another example of saint Geneviève’s protection of the Parisians.102

Eudes de Châteauroux described Parisian processions in his sermon In processione facta propter inundationem aquarum. He re-told to his audience the biblical story of how the ark of the covenant was carried across the river Jordan (Joshua 3), and claimed that: ‘Similarly, in a time of flood, the bodies of the saints are carried. Unless they refuse to move because of our sins, their merits will cause the flooding to cease when their bodies are carried to the scene.’ From the prayer that finished the sermon we learn that the relics carried in this particular procession included those of saint Geneviève.103

By the thirteenth century, the carrying of relics in processions to obtain protection and help in times of disaster was already an age-old custom. We even know that in Italy it was customary to leave some part of the saint’s relics outside the main reliquary so that they could be more easily used in processions. When the bones of Saint Ansanus were transferred to Siena in 1107, one of his arms was reserved to be used as a portable relic against fire and lightning.104

In addition to the relics proper, miracle working holy pictures were also carried in catastrophe processions. The earliest known and one of the most important protective sacred images was the Hodegetria icon of the Virgin and Child in the church of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome. According to tradition Saint Luke painted it. Gregory the Great had it carried in the plague procession of 590. After the plague of 590 it was always carried in Roman catastrophe processions, and it became known as Salus populi Romani.105

Matthew Paris tells in his Chronica Maiora that in late July and early August of 1258 there was a great famine and high-level mortality in England. The previous crop had been a bad one, and the current year’s one was late due to continuous bad weather and rains. The poor were dying in numbers and even the rich would have died had not food been brought in from the continent. Having set the scene, Matthew went on to say that in the absence of any human help, people turned to divine aid. The chapter of Saint Albans abbey decided that all the people were to fast and organise a procession. They were to walk devotedly and barefooted to the parish church of Saint Mary. This procession was arranged on the feast of Saint Oswin (20 August) to ensure the help of the Saint. The example of Saint Albans was followed in London. Matthew ends his story by telling that, with the help of St. Mary (‘advocata nostra potentissima’), the protomartyr Saint Alban, and other saints, the rains soon stopped, or at least became less severe.106

Here we have an example of a careful plan for maximising the effects of the procession. The population of the town was exhorted to fast and perform other penitential activities before the actual procession. The time of the procession was fixed on to the feast of Saint Oswin to secure this saint’s help. And finally, the procession ended in the church of Saint Mary – mater misericordiae and the ultimate intercessor.

The most important point in this case was the timing. Matthew lets us know that it was still early August at latest (‘in confinio Julii et Augusti’) when the famine and rains were harassing people. Then the chapter of Saint Albans decided to arrange a procession. Alas, we do not know the exact date of this decision. However, it is quite likely that it happened sometime in the first half of August. Instead of acting as fast as possible, the chapter decided to opt for a more convenient day, i.e. Saint Oswin’s feast. This is a significant detail when one bears in mind that every single day of delay could mean further loss of life. This suggests that the procession was not just a religious formality that was carried out more or less automatically in time of disaster. The monks of Saint Albans believed genuinely in the usefulness of the procession and wanted to make sure that everything was done under the best possible circumstances.

The next example is from late medieval Sweden, to bring some variety in period and geographical area. Here it is not a question of an actual procession, but rather of instructions how one should be arranged. The anonymous writer gave instructions how the realm can be saved from Divine wrath. Unfortunately, we do not know the exact nature of the disaster in question, but judging from the circumstances a plausible guess would be the plague. After an introduction about the sins of the people and the inevitable divine participants of the Masses were to walk barefooted around their churches and cemeteries, singing hymns and praying. People were also urged to stay in the church until the end of the celebration if it was only possible without great inconvenience. Furthermore, they were to give alms to the poor according to their economic means. In addition to these measures, the preacher declared that a general fast with bread and water should be observed for seven consecutive Fridays. Those unable to fast were expected to give alms and say prayers instead.108

Here we see again that the procession as such was not considered to be sufficient action to placate God. In addition, there had to be other penitential measures to secure a positive outcome. People were to confess their sins and, more interestingly, they were also required to make satisfaction for them. This was done in the form of fasting, almsgiving, and prayers. All these measures are mentioned in any medieval summa de penitentia. As visible signs of humility, devotion, and penance the participants of the procession went barefooted.109

All these penitential activities were known customs in Sweden from the time of the Black Death. There is a 1349 letter from King Magnus Eriksson. It was addressed to the clergy and the laity of the diocese of Linköping. The letter opens with stating that God has sent great pain and sudden death to Sweden to punish the people for their grave sins. It is important to try to placate God and remove His wrath. This can be done, if every Friday all people come to their parish churches barefooted, make a procession around the church with the host, hear mass, and give offerings. Furthermore, everyone was supposed to fast with bread and water on Fridays.110 Interestingly, there is no sign to prove any awareness of the dangers involved with public meetings in times of plague, though we do not know whether this was due to a lack of knowledge, or to king Magnus’ belief that the protective power of processions was great enough to risk further contagions.

King Magnus’ letter can be compared with various surviving exhortations to engage in public penance, prayers, and processions from England on the advent of the Black Death. Among others, Bishop Edington of Winchester ordered the cathedral chapter to recite special prayers, most notably ‘the long litany instituted against pestilences of this kind by the holy fathers.’111

Giovanni Boccaccio describes in the Introduzione to the Giornata prima of his Decamerone the precautions taken by the Florentines against the Black Death. He writes:

‘And there against no wisdom availing nor human foresight…nor yet humble supplications, not once but many times both in ordered processions (in processioni ordinate) and on other wise made unto God by devout persons, – about the coming in of the Spring of the aforesaid year, it began on horrible and miraculous wise to show forth its dolorous effects.’112

On the basis of the examples presented above we may safely conclude that processions were used as a means of combating natural disasters from the Early Middle Ages through the Early Modern Age. Furthermore, they were known in all Christendom. There were regional variations, but the basic liturgy remained the same.

There were clear theoretical models for the organisation of the processions, and allowing for small regional variations these models were on the whole carefully respected. Now that we have gone through some examples of actual processions, and established the continuity of this practise, it is time to analyse these processions more closely. The above-presented descriptions are often rather sparse on details. Consequently we shall have to look at other sources to obtain a more precise picture of what exactly happened during a procession.

How was a procession arranged? Sicardus Cremonensis gives a detailed description of processions in his late twelfth-century liturgical guidebook Mitrale. At the end of the thirteenth century Guillaume Durand incorporated its passage concerning processions into the enormously popular Rationale divinorum officiorum. Durand’s book has survived in numerous manuscripts, as well as in numerous early printed editions. Hence Sicardus’ procession description found its way all over Europe. Sicardus writes that the marching order was as follows: first came the clergy, then in a determined order the religious, nuns, novices, laymen, widows, and finally married women. He also presents a slightly alternative order. Both these orders however hav eone thing in common; the members of the clerical stand were always ahead of the lay people.113

We have seen that the participants of processions were expected to follow a dress code and certain behavioural habits. These are also mentioned in theoretical works devoted to such matters. Guillaume Durand wrote:

‘Litanies are also held because of various other reasons, whence Pope Liberius instituted that in the case of war, famine, pestilence or any other such adversities are imminent there should always be litanies so that we can escape such adversities with the aid of supplications, prayers and fasting.’114

Here we are made to understand that the participants of processions were supposed to have the right religious mentality, and that they were also supposed to fast. Nothing is said about going barefooted, but Sicardus Cremonensis noted that, in addition to fasting participants should wear penitential and mourning clothes (‘in poenitentiali et flebili habitu’), which obviously included going barefooted. Sicardus emphasised also the importance of the participation of all members of the community. He wrote that all people; men, women, and servants should abstain from servile labou rand participate in the processions until they were all over. As everyone had sinned, they should all do penance together.115 It is uncertain if laypeople were always expected to participate. Noël Coulet has proposed that, at least in southern France, the processions were originally a clerical rite, but that there was a progressive growth of lay participation as the processions became a civic issue and were de-clericalised during the fourteenth century.116 However, most of the evidence seems to confirm that lay participation was indeed ruling custom.

We have seen that relics were often carried in processions. Liturgical books confirm this. Guillaume Durand wrote that the crucifix and reliquaries of saints should be at the head of the procession, so that the war banner of the cross and the prayers of saints might expel demons from the way. In addition to the crucifix, there was supposed to be a banner carried to commemorate the victory of resurrection and the ascension of Christ.117

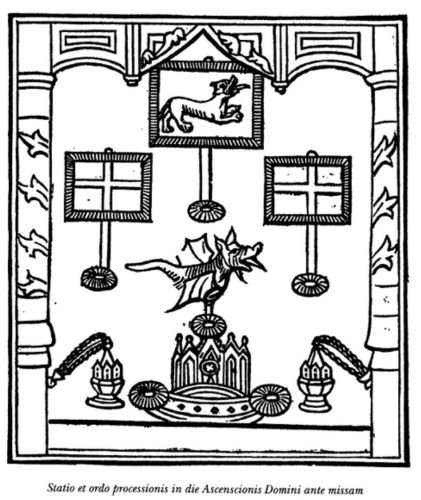

In some areas, it was also customary to carry a banner or statue presentinga dragon. Both Sicardus Cremonensis and Guillaume Durand explained that this dragon symbolised the devil. It was carried before the crucifix and banner of Christ’s victory during the two first Rogation Days. During the last day it was carried behind them. The two first rogation days stood for the first two periods of world history, that is, the time before and during the law, whereas the last day stood for the last period, the time of grace. During the first two periods the devil was the ruler of this world, hence his banner was carried first in the procession. Yet in the time of grace Christ had defeated him. After his defeat, the devil no longer was able to harm Christians openly. He could only try to seduce them to fall trough suggestions, and thus his banner was also kept behind the insignia of Christ and saints.118 The early fifteenth century German preacher Johannes von Werden confirmed these details concerning the carrying of a dragon image as told by Sicardus and Guillaume, and specified that in his time this custom was mainly used in France.119

Diana Webb suggests that this curious presentation of a dragon may have signified also the plague that Gregory the Great had hoped to avert from Rome with the original Major Litanies.120 Some folklorists and historians have proposed that the mocking parade of the dragon the city commemorated its own foundation in a region now purged of all traces of rurality and wild beasts. For those historians Rogation Day processions were essentially an urban phenomenon. According to André Vauchez ‘clerical interpretation of the monsters in the procession precluded any other reading, particularly the obvious one which would establish a relationship between the attention paid to the tail of the monster, the organ in which its potency was concentrated, and fertility rites.’121 As interesting as these hypothesis are, in lack of confirming evidence it seems to be safer to believe the explanation put forward by Sicardus Cremonensis and Guillaume Durand.

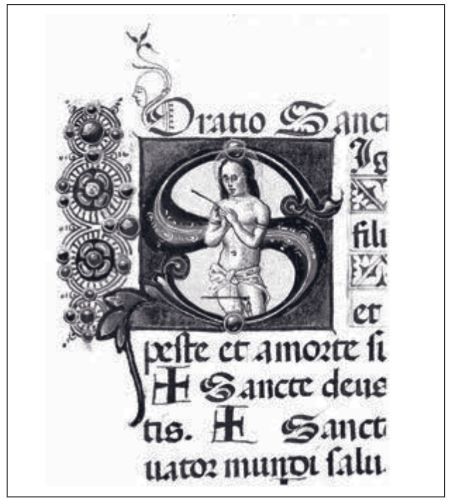

Gary Dickson emphasises that the flagellant movement of 1260 in Perugia was originally a religious revival well within the limits of catholic orthodoxy. In it the old monastic habit of penitential flagellation was fused to penitential processions of the Church.122 And indeed, the best sources that allow us to understand the real character of orthodox medieval penitential processions are those illuminated manuscripts that present scenes with participants of flagellant movements. Leaving aside the actual flagellation, we may observe that such pictures present all the features of penitential processions described by Guillaume Durand and Sicardus Cremonensis. There are barefooted penitents, crucifixes, and presentations of the dragon.123

We know from the ordinary Rogation Day processions that they either went around the church from where the procession started and returned there, or that they headed to some other church (known as the station church). In both cases, at the final destiny a Mass was eventually celebrated at the final destination.124

It seems that processions pro causa necessitatis, might occasionally have ended up at the place where the actual problem was situated, for instance the riverbank in the case of a flood. Nevertheless, in most cases the processions either returned to the place from where they originally started, or ended up in some station church, perhaps a church dedicated to a saint whose aid was summoned.

Sometimes the procession did not move from place A straight to place B, but rather went around the village or town in question “beating the boundaries of the parish”. Walking around the walls of town made sense, because all the people of the community were living inside the walls. Thus the procession formed a sphere of protection against the plague, which unlike a flooding river, was something that men could not localise. Choosing a circular route was a common custom in processions performed because of epidemics.125 The circular route was also used to mark the confines of the community, for a procession was seen as a collective act that defined the identity of the community over against that of neighbouring parishes.126

While the procession was on the move, antiphons were sung as well as the litany of the saints, and the seven penitential psalms were (according to the length of the passage). The lay participants were expected to show their contrition in other ways.127 Here it is not possible to go into details about the exact psalms, hymns and prayers that were used, for even though the general outlook of religious processions remained very much the same in different parts of Europe, there were differences in local customs. Some prayers also differed according to the problem in question.

To underline this variety of possibilities we can take an example. In the processions organised according to the Salisbury use there were different antiphons for different kinds of situations. For instance,

For rain:

Aridaverunt montes, siccaverunt

flumina, terra fructum negavit;

dona nobis pluviam: non peccavit

terra nec radices montium, sed nos

peccavimus; parce nobis, Domine,

dona nobis pluviam.

For the end of rain:

Inundaverunt aque, Domine, super

capita nostra; invocavimus nomen

tuum de lacu novissimo ne avertas

faciem tuam a singultu nostro.128

These antiphons and numerous others which have survived are yet another concrete example of the penitential mood of the processions. The first one emphasises the role of sin as a reason for the drought: ‘It is not the land which has sinned, not the mountain valleys; it is we who have sinned; spare us, Lord, grant us rain.’ The second antiphon does not mention sin and penance explicitly, but their presence is obvious, for it says: ‘do not avert your face from out tears.’129 Tears were considered to be the evident sign of contrition,130 which was the first step in the penitential process. It was followed by confession and, lastly, satisfaction.

On the basis of the theoretical instructions and actual cases described above we may now present a general picture of medieval catastrophe processions. First of all, it is significant to note that none of the cases presented above were spontaneous actions taken in a state of great religious fervour, but rather well-planned and carefully coordinated operations, generally orchestrated by the ecclesiastical authorities. Sometimes the initiative of organising processions came from lay authorities, as was the case in the above-described case of Swedish King Magnus’ letter.

Let us look more carefully at who were the people on whose initiative these processions were held. According to Nicole Hermann-Mascard, processions, both ordinary feast day and processiones causa necessitatis, always needed to have the authorisation of the local bishop.131 The role and acceptance of the bishop seems to have been important in many processions. In the case of Soissons, we find that the procession was inaugurated by the bishop with the co-operation of the abbot of Saint Médard abbey.

The organisation of the flood processions in Paris was rather similar. High town officials (prévôt des marchands and councillors) turned to the bishop and expressed their wish that the relics of saint Geneviève should be carried processionaliter to Notre-Dame. Then the issue was discussed in the parliament of Paris. If the decision was taken to arrange a procession, it was up to the bishop to ask the permission of taking out the relics from the abbey of Saint Geneviève. The abbey could, at least theoretically, deny it. In practice, the abbot asked the bishop whether it was a question of extreme necessity. After the bishop had confirmed this, the permission was given. Once all was clear and a time was set, a public sermon was held in the church of Saint-Étienne to inform the Parisians of the approaching event, and how they should prepare themselves for it.132 The role of bishops was obvious also in above-mentioned processions, and in the public prayers organised in context of the Black Death. Not only were the bishops summoning people to participate in processions, but they also encouraged them with special indulgences.133 The bishop’s role in organising catastrophe processions was also decisive in the late fifteenth-century Angers.134

In several cases, however, bishops are not mentioned. Matthew Paris provides a good example with the procession organised by the monks of Saint Albans to stop continuous rains. The chapter carried out the planning and organisation, and no doubt, also by the abbot of Saint Albans monastery, though we do not know that for sure. This, of course, does not necessarily mean that the monastery did not ask the permission of the bishop.

In the two mentioned cases from late medieval Sweden, the instructions come from King Magnus Eriksson and the anonymous preacher of the Uppsala manuscript. The king gave orders to arrange penitential processions on his own right. In the case of the anonymous preacher there is no mention of Episcopal permission. The preacher merely said what needed to be done. As we do not know his identity, we can only speculate with what authority he did so. We only know that the manuscript was quite likely written in the Vadstena monastery in the beginning of the fifteenth century, probably by an anonymous Bridgettine monk. We do not know whether the text itself was written by that monk or was he merely copying another, older text.

When locusts attacked the city of Marseille and its surroundings threatening to cause major damage to crops, the elders of different guilds decided that there should be ‘processiones ecclesiarum et intercessiones apud Deum et etiam per universum populum huius civitatis processiones sequentes cum omni contritione.’ Thus the initiative came from the part of the temporal authorities and participation was considered to be duty of every citizen.135

Were there any instances of processions held on the popular initiative or as expressions of popular devotion and religious commitment? It has been argued that the 1260 penitential processions of the flagellants in Perugia were inspired by a certain Raniero Fasani a layman and frate della penanza.136 Whether the originator was Raniero Fasani, someone else, or just the public spirit does not really matter. The important thing is that despite the participation by some members of the clergy, the flagellant processions seem to have been essentially a lay movement. Nevertheless, one has to remember that the flagellants were an anomaly, not a common occurrence. Therefore, it is open to discussion whether these flagellant processions can be called processions in the proper sense of the word.

Occasionally, the initiative for organising penitential processions came from the mendicant preachers who saw catastrophes as a signs of God’s wrath. A fine example is the pestilence sermon of Franciscan Bernardino de Busti, which is included in his model sermon collection Rosarium sermonum. Bernardino asked what a sinner ought to do in the face of pestilence, and said that taking flight was no protection against God’s wrath, for His punishment follows sinners everywhere. After dismissing other possibilities, he provided the real solution: ‘Go then, and reconcile you with God, and pray to the Blessed Virgin, so that she might intervene on behalf of you and this city.’

Bernardino described in detail how reconciliation with God is possible, and presented the processions of Gregory the Great as an example to follow. Interestingly in Bernardino’s version, Rome was not saved solely because of the penitential activities ordered by Pope Pelagius and carried out by his more famous successor Gregory the Great, but also because of the intervention of Holy Virgin.137 Perhaps he felt it impossible to leave aside the Mater misericordiae, when preaching about such mercy. This Mariological emphasis is, of course, something one would expect from fifteenth-century Franciscan. Whether such exhortations, which no doubt were common during catastrophes, played any significant role in deciding the course of action, we cannot know.

Other questions which ought to be asked are whether people actually took an active part in these processions and did they believe in their efficiency. We have already discussed the problems connected with the possibilities of knowing the actual level of participation and the motives of the participants. As said, there are numerous chronicles and other sources, which do not hesitate to describe the multitudes of people who took to the streets with religious fervour. In the Parisian processions of 1412 there were tens of thousands of people. Frequently, the sources neglect to give absolute figures and use only expressions such as ‘trés grande people’, ‘tant de peuple quesans nombre’ or ‘grant multitude’.138 One is tempted to think that either the sources are exaggerating or that people were not participating of their own free will, but were rather manipulated or forced to participate. Indeed, we know that during the Parisian processions of 1412 there were instances when attendance was compulsory.139

We do not know how typical the processions of 1412 were, yet there seems to have been far more processions than in an average year. However, even if participation was not normally obligatory, it was rather difficult to stay out if the majority joined in. It would have meant turning one’s back to one’s own community at the moment of danger, and in general, those not participating in the collective religious activities of the parish were perceived as bad neighbours.140

When it comes to the real motives and behaviour of participants, there is some fragmentary evidence that they did not always take processions very seriously, at least from the point of view of the clergy. In his Rogation Day sermon Johannes von Werden complained that in his time many people turned processions into a laughing matter and jokes, and that therefore God was punishing the world.141

In his second Rogation Day sermon Federico Pisano Visconti refers to the long walk the participants had already gone through, and adds that he is therefore going to preach only briefly. He also exhorts his audience to pray to Saint Peter so that he might intervene on behalf of them in such a manner that the preacher may preach as planned in advance, and that the congregation will listen to him.142 Apparently Federico was not totally convinced of his audience’s stamina and good will in listening to a long sermon after the prolonged procession. This implies that not everyone was overtaken by fervent devotion when it came time to go processionaliter.

Johannes von Werden and Federico Pisano Visconti both referred to ordinary Rogation Day processions, not to processiones causa necessitatis. It is very likely that at the time of danger, the attitudes of the congregations were more appreciative and pious. When the procession was organised to remove an acute problem at hand people were bound to have been better motivated and to have been in the right mood for it.

This can be illustrated by the surviving descriptions of flagellant processions and other late medieval sources. The Journal d’un bourgeois de Paris describes processions organised because of the flood and cold weather in June 1427. According to the diary, it was so cold that there was not a single grapevine with flowers. This was, of course, was exceptional for June. The diary states that around that time there were pious processions in Paris and in the neighbouring villages. Men, women, children, young, and old attended these processions, and nearly everyone went barefooted. There were crosses and banners, and the participants were singing hymns and praises for the Lord.143 This description seems to convey a genuine sense of piety and devotion.

Processions were nearly always organised in line with instructions from ready-made liturgical manuals. They closely followed the liturgy of Rogation days. Usually the initiative came from the higher clergy. Thus, catastrophe processions were not ad hoc expressions of popular religious fervour in times of need, but rather carefully planned and organised collective actions performed during a longer lasting catastrophe situation.

Sermons144

Larissa Taylor, who has studied preaching in late medieval and reformation France, writes about catastrophe sermons:

‘Procession sermons and those given at the condemnation of a heretic were also common. But another “occasion” for preaching had largely disappeared by the end of the Middle Ages—that of charismatic, prophetically preaching during times of catastrophe.’145

However, part of the difficulty with this comment is that it is neither easy nor advisable to draw a rigid distinction between ‘procession’ sermons and ‘catastrophe’ sermons. Moreover, while there is much evidence from England of bishop’s mandates calling for prayers and processions at times of national or local emergency, the evidence for the sermons that were associated with the processions is much more vague and it is not clear to what extent these sermons always took place.146 Nevertheless from surviving mandates it is clear that there was a considerable overlap between what is here called the ‘catastrophe’ sermon and the ‘procession’ sermon: a sermon about an earthquake is clearly a ‘catastrophe’ sermon, and a mandate for prayers and processions for the health of the king would clearly generate a ‘procession’ sermon, but a sermon against a prevailing plague may be a ‘catastrophe’ and ‘procession’ sermon combined. This potential confusion makes it even more important to emphasise that catastrophe sermons, as they will be called from here on, were simply a part of the catastrophe liturgy, which was developed on the basis of normal penitential liturgy.

The aim of this chapter is to establish the fact that catastrophe sermons had not disappeared by the end of the Middle Ages, not even in France. On the contrary, it was a fairly common custom to preach in connection with different catastrophes. This is confirmed by two arguments. The first one is that the rather small number of surviving catastrophe sermons does not actually prove that such sermons were uncommon. The second argument is that there are considerably more surviving catastrophe sermons than has previously been thought. They were simply not always written down under that name.

Actual Catastrophe Sermons

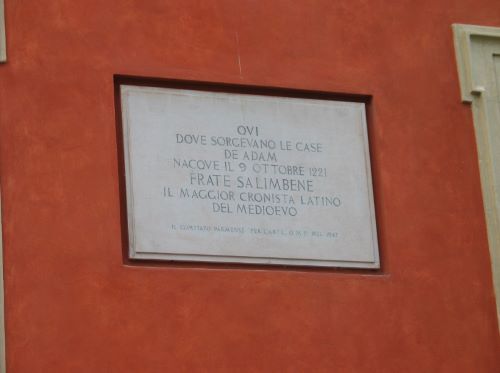

We can gather information about catastrophe sermons in two different ways, that is, going through all kinds of secondary evidence, and reading the surviving sermons themselves. There is some research on secondary evidence for catastrophe sermons. Oliver Guyotjeannin, who has analysed the chronicle of Brother Salimbene de Adam, states that Salimbene’s descriptions of natural catastrophes are in most cases also meant to serve as material for his fellow preachers. Salimbene gives them suitable themae to be used when preaching on such occasions.147 Even if Salimbene’s chronicle does not prove that these themae were ever used, it is obvious that Salimbene knew that his fellow Franciscans did indeed preach on such occasions. Otherwise, it would have been pointless to provide them with suitable themae.

In this context, it is also important to acknowledge the work of Herve Martin on preaching in late Medieval Northern France. He uses vast numbers of chronicles, as well as fiscal sources concerning payments to preachers. From these sources, he has managed to find information about 1147 sermons between the years 1350 and 1520 (i.e. roughly the period studied by Larissa Taylor). For 262 of these sermons he has been able to identify the context of preaching. Nine of these sermons were held in connection with some natural disaster (calamités, épidémies). On the basis of this evidence he concludes that sermons as a part of “religion panique” were fairly common in late medieval France.148

It should be remembered that absolute figures are always open to different interpretations, and it is rather hazardous to judge whether these sermons were fairly common or not. However, I am willing to postulate that Martin’s evaluation is correct. There are even indications that catastrophe sermons were underrepresented in Martin’s sources.

There are similar indirect sources from England. For example, in a study of the registers from the diocese of Lincoln, Alison McHardy has shown that there were fifty-one occasions during the period of the Hundred Years War (1337–1453) when special prayers were requested. Although most of these – thirty-four in total – concerned the war with France, some were against natural disasters such as repeated outbreaks of plague.149

It can be argued that catastrophe sermons were different compared to other sermons, because they were held in times of acute crisis. This may sound obvious and trivial, but it is not really. In times of acute disaster, it was not normally a question of hiring a famous preacher to deliver sermons to the people. Catastrophe sermons were meant to urge audiences into immediate contrition and penance, to avert the disaster. Hence, there was no time to seek out the most popular and famous preacher. It was more important to act fast. After all, what might have been lacking in the skill of the preacher was probably compensated for by heat of the moment. Under such dire circumstances, the audience was normally receptive and less interested in ridiculing a clumsy preacher or seeking aesthetic contemplation from the sermon.

This leads us to assume that members of the local clergy most likely delivered catastrophe sermons, unless some famous preacher happened to be conveniently present. It is highly questionable whether local priests or friars were paid for delivering catastrophe sermons. If they were not, then there were no fiscal records produced to tell modern scholars about these sermons.

There are also problems with using chronicles as sources for catastrophe sermons. Many chronicles usually report disasters and other unusual natural phenomena, but, only rarely do they allow us to know what was actually done about the situation. It was quite exceptional for a chronicler to write down that a sermon was given. The absence of such information does not really prove that such a sermon was not delivered. The very fact that such sermons occur at all in chronicles makes it very probable that they were actually fairly common.

It will suffice to present just one concrete example of a late medieval catastrophe sermon described in secondary sources. There was a major flood in Paris in 1426, and the so-called Journal d’un Bourgeois de Paris describes that this threat was dealt with by organising a traditional procession to Notre-Dame. A mass was held in honour of the Holy Virgin, and afterwards the Franciscan Friar Jacques de Touraine delivered a very pious sermon to the congregation.150 Of course, we do not know what frere Jacques exactly preached, but it is sensible to assume that his sermon had something to do with the reason of the whole procession.

If we turn to the primary evidence, that is, the surviving medieval catastrophe sermons, we find that the corpus is not particularly large.151 The corpus of surviving catastrophe sermons appears even smaller, if one compares it to the number of all surviving medieval sermons.152 This would seem to imply that catastrophe preaching was indeed a vanishing art. However, several questions need to be addressed before any rational conclusion can be drawn concerning the real numbers of catastrophe sermons and their importance. First of all, one might ask whether the number of catastrophe sermons is really as small as it seems.

The surviving medieval sermons have not come down to us according to a random selection taken from all the sermons that once existed, but according to a certain mechanism that preferred certain types of sermons to survive toothers. The huge majority of surviving medieval sermons are contained in model sermon collections. These were in most cases organised according to the liturgical calendar. There are four important categories of such model sermon collections, namely sermones de tempore/dominicales, sermones quadragesimales, sermones de sanctis and sermones de communi sanctorum.153

It was difficult to fit catastrophe sermons into these collections, because floods, earthquakes and other such natural disasters obstinately refused to follow the liturgical cycle. Those rare exceptions that we find in these collections are often found in sermones de communi sanctorum collections, which frequently included sermons for different occasions, such as visitations, chapters, and the consecration of new churches.

All these arguments taken together make it obvious that the possibility for catastrophe sermons to make it into a model sermon collection, or to be recorded in fiscal sources and chronicles was rather small. Therefore one cannot argue that since very few medieval catastrophe sermons survive, such sermons were preached only rarely. In fact, all things considered, it seems reasonable to assume that such sermons were in reality rather common.

Two additional facts support this conclusion. The first one is that the few surviving sermons come from different centuries and from different regions of Europe. Eudes de Châteauroux preached in thirteenth-century France and Italy, whereas Bernardino da Busti wrote his sermons in Italy during the last quarter of the fifteenth century. We have even one example from late fourteenth- or early fifteenth-century Sweden. This seems to point to a custom that was spread throughout Christendom.

Secondly, we know that the habit of delivering catastrophe sermons outlived the Middle Ages. They are mentioned in sources concerning the Great Lisbon earthquake of 1755 and on many other occasions.154 If the custom of holding catastrophe sermons had vanished, or become very uncommon during the later Middle Ages, it must have been re-invented at the beginning of the early modern period. I do not find this very plausible. It is far more logical to assume that the custom never died out.

Now that we have established that the surviving evidence does not allow us to measure the frequency of catastrophe preaching, we may move on to another argument; one that supports the theory that catastrophe preaching was common.

Rogation Day Sermons

It has been argued that there is only a very small number of surviving catastrophe sermons. This is correct only if we count the sermons that are clearly titled as catastrophe sermons. However, this situation changes dramatically if we take into account other sermons that could have been used as catastrophe sermons. My hypothesis is that Rogation Day sermons were often written in such a manner, so that in case of an emergency they could easily be converted into catastrophe sermons. Systematic comparison between Rogation Day sermons and catastrophe sermons points in this direction.155 Before examining this evidence in some detail, it is worthwhile to take a look at Rogation Day sermons on a more general level, for they are interesting to this study in their own right.

These sermons were meant to be delivered during the three Rogation Days before Ascension Day. Generally speaking, most of these sermons concentrated on two major issues, namely prayer and confession. People were instructed how to pray, where and when they were to do it and, most of all, what constituted the righteous and suitable subjects of prayer. A good example is Konrad Holtnicker’s second Rogation Day sermon. It has a threefold division that is built around praying. The first part focuses on the true needs of the people as opposed to those things they falsely imagine to be their needs, such as temporal goods. The second part of the division is about how one should pray. The final part deals with the generosity of God who will surely concede anything to those who pray righteously.156 This pattern in treating prayer is repeated with minor changes in numerous Rogation Day sermons.

Sometimes these sermons deal in a very detailed manner with the matter of confession. A good example is Konrad Holtnicker’s seventh sermon in rogationibus. It very closely resembles a manual for penitents. It has a four-fold division. The first part tells audiences that they are supposed to confess to learned priests, who have the necessary skill to handle the sacrament. Konrad does not forget to say that in case of extreme necessity, that is, mortal danger, it is also possible to confess to a layman or, if there is not even a layman available, directly to the supreme penitentiary, that is, God.

In the second part of the division, Konrad tells his audience that they should confess their own sins, not those of others. Furthermore, they should confess all their sins, even the venial ones. This must be done either according to the sins against the Ten Commandments, or according to the Seven Capital Sins and their progenies. The third part of the division informs audiences that they must confess while they are still in this world, for in the other world it will be too late. Conrad exhorts them to confess four times in a year. Echoing the famous 21st canon of the IV Lateran Council, he also reminds his audiences, that even if they are not willing to confess four times a year, they are nevertheless obliged to do so at least once a year. The fourth part of the sermon is about how one should confess, and there Conrad refers his readers to another sermon where he already had considered this subject.157

In many sermons, the topic of confession was neatly bridged together with the topic of praying by stating that God overlooks the prayers of sinners. The secret of effective prayer therefore lies in confessing ones sins before praying. In fact, confession can be seen as part of the proper praying process. Bertrand de Tour wrote in his sermon:

‘Sins are impediments to a worthy prayer. God rejects the prayers of the sinner for they are not worthy of being heard. Hence God says to sinners in Isaiah 1: “And when you stretch forth your hands, I will turn away my eyes from you: and when you multiply prayer, I will not hear. For your hands are full of blood”, that is, sin.’

He gave the solution in the next passage:

‘If a sinner wants to pray to God in a worthy manner he has to leave behind his sins and turn to God. No one can leave sins and turn to God unless through sacramental penance, one part of which is true conversion, which comes after true contrition and before real satisfaction of one’s sins. Such a confessions therefore comes before worthy prayer, and if it does not, then the prayer is not worthy to be heard. Therefore let us confess one to another, as it is presented in above quoted epistle.’158

This way of connecting prayer and confession with the passage from the first chapter of Isaiah seems to be one of the common topoi of Rogation Day sermons. It can also be found in sermons of Conrad’s fellow Franciscan Jean Rigaud,159 and in the late medieval sermon collection of Johannes Herolt.160

Unlike that of Konrad Holtnicker, Bertrand de Tour’s sermon does not read like a manual for sinners going to confession. Nevertheless, he does not fail to mention the three parts of the confessional process, namely contrition, confession and satisfaction. The emphasis on the sacrament was probably meant to encourage the audience to confess more often and more willingly, at least that is the impression one gets when reading large numbers of Rogation Day sermons.

Now that we have given a short description of the nature and functions of Rogation Day sermons, it is time to proceed with the stated hypothesis, namely that Rogation Day sermons were easily converted into catastrophe sermons. In fact, I am willing to hazard a guess that this was not just a theoretical possibility, but also the prevailing practise. This hypothesis is nearly impossible to prove categorically, but there are six arguments to justify such an assumption.

First of all, we may notice that the processions that were organised during the Rogation time were originally intended to protect people against natural disasters. As we have seen, these same litanies and processions were often adapted and used in connection with some major catastrophe. If the liturgy of Rogation time was easily converted to be used in case of natural cataclysms, then why not also Rogation time sermons, which, as we have seen, were often an integral part of that liturgy. Even if the sermons were not necessarily part of the liturgy, they nevertheless reflected and reinforced the same theological ideas as Rogation time liturgy.

The second argument is that in Rogation Day sermons preachers often dealt with natural disasters when reminding their audiences of the origins of the Litanies. It was customary to tell stories of the plague in Gregory the Great’s Rome and different catastrophes in Mamertus’ Vienne. Normally this was done at the beginning of the sermon to establish the historical background and the theological justification for the Litanies. When doing this, the preachers, accidentally or intentionally, influenced their audiences to deduce that what they were actually praying for God’s protection against catastrophes, such as the Plague in Rome in Gregory’s time or the earthquakes in Mamertus’ time.

A good example of sermons expounding the history of the Litanies is the first Rogation Day sermon by Federico Visconti Pisano, archbishop of Florence. It was delivered in vernacular sometime during his episcopate (1254–1277). Federico explains carefully all the details connected with the invention of Rogation Days by Gregory the Great and Mamertus of Vienne. Federico Visconti’s sermon is very rare as it is one of the few Rogation Day sermons which we know for sure were actually delivered, not only written to serve asa model sermons.161

Federico was by no means the only preacher to tell the history of the Rogation Day Litanies. The nearly contemporary Franciscan preacher and theologian Bertrand de Tour expounded the same history in his first sermon In rogationibus.162 Johannes Herolt explained in his sermon’s introductory part why Rogation Days were celebrated by the Church, and what should be prayed for. He explained that there are three things that people ought to ask from God and His saints. Firstly, that God would end wars, which were especially common during spring, that is, at the time of the Rogation Days. Secondly, that He protects and multiplies the crops. Thirdly that He makes people ready and able to receive the Holy Spirit.163 Here we can reason that protecting the fields would imply keeping floods, draughts and storms away. With another fifteenth century preacher known as Meffreth we get even more explicit information. He wrote that on Rogation Days the Church asks protection against epidemics, conservation of crops and rains to help them grow.164

Johannes von Werden wrote that on Rogation Days we ought to pray for four things: remissions of our sins, divine grace, an eternal home in heaven, and lastly liberation from our tribulations. According to Johannes, these tribulations are hunger, pestilence, and wars. Then he continued with a very detailed description of the origins of the Litanies.165 These specifications of just what people were actually supposed to pray for during the Litanies make it rather difficult to draw a line between Rogation Day sermons and catastrophe sermons. Both seem to be first and foremost concerned with natural disasters.

The third argument is that both sermon types use occasionally the same biblical passages as themae. This is significant because the themae for different liturgical times and different occasions overlapped rarely if ever. When we find that the same themae were used for both types of sermons, we can safely assume that these sermons were essentially interchangeable.

The themae for preaching were normally taken from the Gospel or Epistle readings of that particular Sunday. Gospel readings were often preferred over Epistle readings and the Rogation Day sermons are no exception to this rule. However, the choice of the themae in Rogation Day sermons is somewhat exceptional. Most preachers used the thema ‘Petite et accipietis’ (John 16:24), whereas the actual reading of the day would have been Luke’s version of the same speech of Jesus (Luke 11:5–13). The probable reason for this change is that John’s laconic quotation was rhetorically more efficient than Luke’s reading ‘Petite et dabitur vobis’. Even if the ‘Petite et accipietis’ was by far the most common choice, there were also other possible themae. Some preachers, for instance, chose to use the theme ‘Amice accomoda mihi tres panes’.

In the case of Rogation Day sermons, we have a fairly large corpus of sermons using the Epistle reading as a source for the thema. The Epistle of the day was James 5:16–21 and the themae most frequently taken from it were ‘Confitemini alterutrum peccata vestra’ and ‘Elias oravit et caelum dedit pluviam’.

If we look at the themae used in the few surviving catastrophe sermons, we find that some of the Rogation Day sermon themae were also used for catastrophe sermons. The Epistle text ‘Elias oravit et caelum dedit pluviam’ is used in three out of thirty surviving catastrophe sermons. These are Nicolas de Gorran’s sermon Ad impetrandam pluviam, Jacques de Lausanne’s sermon Ad impetrandam pluviam, and Giovanni Regina da Napoli’s sermon In processione pro pluvia impetranda.

Furthermore, two other catastrophe sermons use a variation of this themae taken from the same Epistle text, that is, sermons of Guillelmus de Sequavilla and Nicolas de Gorran’s sermon Ad impetrandam serenitatem. If one looks at these five sermons there are two interesting things to notice. The first is that Dominican friars wrote them all. Whether this is just a coincidence or has some significance is impossible to establish here. It is, nevertheless, interesting. Another striking feature, far more relevant for the present purpose, is that all these sermons deal with the problems posed by drought or heavy rains.

This connection with only one category of natural disasters, that is, those involving water, leads one to wonder whether the fact that these sermons use common themae with Rogation Day sermons could be merely a coincidence. James’ letter simply happens to be a very good passage for anyone hunting for a suitable thema when preaching on floods or droughts. This passage would inevitably come up if a preacher were looking for the word pluvia in a biblical concordance. Even if we reject the possibility of mereco-incidence, it is only reasonable to point out that five sermons is hardly conclusive evidence.

The fourth argument to support the hypothesis that the Rogation Day sermons could have been used as catastrophe sermons is that the most important issues dealt with in these two genres of sermons are the same. Both strongly emphasise the meaning of penance and prayer. Sometimes the similarities are so striking that without seeing the title of the sermon it would be very hard to tell which sermon is which.

In his first sermon Ad impetrandam pluviam, the Dominican preacher Nicolas de Gorran writes that drought is a punishment from God brought upon us by our sins. Nicolas quotes Jeremiah to emphasise this relationship between sin and drought: ‘Our sins have withholden good things from us.’166 The only way to find liberation from this punishment is to reject sin and beg God for mercy. This is achieved through penance and prayer. Even the thema of the sermon (‘If heaven shall be shut up, and there shall be no rain, because of their sins, and they, praying in this place, shall do penance to thy name, and shall be converted from their sins, by occasion of their afflictions, 3 Kings 8:35’) reflects this emphasis on penance and prayer.

Another Dominican, Giovanni Regina da Napoli, wrote that the roots of trees and plants could not draw water from dry soil. Therefore they cannot flourish if the earth is not irrigated. Such is also the case with sinners. They lack the humidity of Divine grace, and therefore, as an external sign of this, God will not let the rains fall upon them. The solution to the problem of drought was penance. Once the people have purified themselves from their sins, they are recommended to turn to God, to pray humbly for rain, and they will surely receive it. Giovanni rounds up his argument by quoting Mark 11:24: ‘Therefore I say to you, all things, whatsoever you ask when ye pray, believe that you shall receive; and they shall come unto you.’167

These two sermons follow the typical pattern of Rogation Day sermons. Proof of this similarity can be obtained by comparing these two sermons with the Sermo in rogationibus by the contemporary fellow Dominican Aldobrandino da Toscanella. He used the theme Confitemini alterutrum peccata vestra, and divided it as follows:

‘The most important reason for the deprivation of spiritual and temporal goods is sin. Jeremiah 5: “Our sins have withholden good things”, the good in its spiritual category, and the good in the sense of abundance of temporal goods. Take heed that saint James with these words exhorts us principally to three things. Firstly to the hatred of sin through confession: “Confess your sins one to another.”…. Secondly he exhorts us to gain good things through prayer: “Pray one for another, that you may be saved.”….Thirdly he exhorts us to accumulate merits…’168

The similarities in approach between these three sermons are obvious. In fact, the only significant difference between Nicolas de Gorran’s or Giovanni Regina da Napoli’s sermons and that of Aldobrandino da Toscanella, or of any other typical Rogation Day sermon, is that in catastrophe sermons the threat is named (the lack of rain). It would have been easy to use Aldobrandino da Toscanella’s sermon with slight modifications as a catastrophe sermon.

The fifth argument is that in addition to the central issues of prayer and penance, there are also similarities in numerous less important details, such as biblical quotations used as arguments and other literary topoi. Indeed, one such similarity can be seen in the above presented examples. Both Nicolas de Gorran’s sermon Ad impetrandam pluviam and Aldobrandino da Toscanella’s Rogation Day sermon quote the same passage of Jeremiah (5:25) when they argue that sin is the cause of temporal misfortunes. Pelbartus of Themes war repeats this quotation in his Rogation Day sermon as well.169

Another example of such a common topos is the use of Jeremiah 3:2–3: ‘And thou hast polluted the land with thy fornications and with thy wickedness. Therefore, the showers were withholden, and there was no lateward rain.’ Bertrand de Tour uses it in his second Rogation Day sermon when underlining the importance of penance to avoid earthly punishments from God.170 Giovanni Regina da Napoli uses the very same passage in his sermon In processione pro pluuia impetran-da.171 The only difference is that where Bertrand is discussing temporal misfortunes brought about by sin in general, Giovanni is concentrating on one specific form of catastrophe – hard rains.

A third example is the anonymous sermon Pro serenitate uel sanitate in MS Vat. Burghes. 138. The preacher is expounding the three conditions that need to be fulfilled so that people can ask favours from God without fear. The first condition is that the petitioner should be worthy to pray to God, for ‘God is not in the habit of listening to others, John 9: “We knoth that God doth not hear sinners.”’172 The Franciscan friar Nicolaus de Aquaevilla refers to the same passage in John in his Rogation Day sermon. Nicolaus is dealing with exactly the same subject. He presents three reasons why God does not always hear our prayers:

‘It should be noted that God does not always listen to us nor does He always give to us what we ask. There are three reasons for this. The first is the indignity of the petitioner, because man in mortal sin does not deserve that God hears his prayers, hence John 20 says about the blind man whom the Lord gave sight and who, having got his sight back said angrily [that is, being angry to the Pharisees who were interrogating him] about Jesus: “We knoth that God doth not hear sinners.”’173

Nicolaus and the anonymous preacher of the Pro serenitate uel sanitate were both writing of what could be called The three obstacles of prayer topos. It was very common in Rogation Day sermons. In thirteenth-century sermons, this topos is normally repeated in its original form, whereas in late medieval sermons one finds that the number of obstacles to prayer varies from one sermon to another, yet the original three were always included. The quotation of John 9:31 seems to have been an essential part of this topos. In addition to the sermon of Nicolaus de Aquaevilla, we find it included in Rogation Day sermons of Johannes Herolt and Pelbartus of Themes war.174

Finally, there is a quotation from Isaiah. Bernardino Tomitano da Feltre writes in his sermon De flagellis Dei et que sunt signa that God allows some time for sinners to mend their ways, but once they have become evil enough, He does not want to listen to them anymore. Here Bernardino quotes Isaiah 1:15: ‘And when you multiply prayer, I will not hear.’175 The same passage can be found in numerous Rogation Day sermons.176

The sixth, and final, argument is based upon two interesting sermons that establish direct and explicit connections between Rogation Day sermons and catastrophe sermons. The first one is the third Rogation Day sermon of the friar minor Jean Rigaud. It has the following title description: ‘Theme from the same day of saint Mark during Rogation time. It can be applied whenever there is a procession for obtaining rain, or serenity, or because of any other tribulation.’177

The other sermon is the exact mirror image of Jean Rigaud’s sermon. It is a catastrophe sermon delivered on Saint Mark’s Day, that is, in connection with Rogation time. The Observant Franciscan friar Bernardino Tomitanoda Feltre preached this sermon in the city of Pavia in 1493. The title of this sermon is Feria quinta post secundam dominicam post pasca in die sancti Marci. De peste. It was probably preached in connection with the Major Litany processions, for the first lines of the sermon include the common explanation why Litanies are organised in that time of the year.178

One must remember that thus far these two sermons are the only known cases that explicitly makes the connection between these two genres of sermons, although, there may very well be more in the numerous uncharted medieval sermon manuscripts. Therefore, considering all the evidence presented, it is plausible to assume that it was customary to use model sermons for Rogation Days also for natural disasters.

This would mean that the alleged disappearance of catastrophe sermons during the Late Middle Ages cannot be taken at face value. Some sources do provide information about catastrophe sermons that were actually held, and some catastrophe sermons have survived in written form. More importantly, however, in the form of Rogation Day sermons there was a nearly endless store of potential catastrophe sermons to be used in case of need. One might object that all this does not prove that these sermons were actually used for this purpose. There is not any positive evidence to prove the opposite. Considering the fact that other traditional means of reacting to catastrophes (i.e. specific masses, processions and prayers to saints) were used all the time, it seems more than plausible to assume that so were Rogation Day sermons. This becomes even more plausible if one takes into account that catastrophe sermons were widely used during the early modern age. It would be more than odd, if they had disappeared for two hundred years only to reappear with the dawn of the modern period.

Putting together the actual surviving catastrophe sermons and Rogation Day sermons in de tempore collections, we get a complete picture of the character of catastrophe sermons, and how often they were used. According to David d’Avray, there were two kinds of preaching. First of all there was revivalist preaching, designed to have an immediate effect on feelings and action. The actual message of these sermons was not the most important point; it was to produce desirable effect on the audience. Then there were the model sermons that were repeated year in year out. They had a long-term impact on the listeners. The same or similar topoi were repeated time after time until they were transformed into popular assumptions.179

In a certain sense catastrophe sermons were an overlapping genre – they belonged to both of these groups of sermons. One might think that both Rogation Day sermons and actual catastrophe sermons were in fact all catastrophe sermons. The difference is in their timing. When preached in their original context, Rogation Day sermons were preventive measures against disasters. They circulated in model sermon collections in a standardised form. As such, they were routinely preached every year in connection with the Rogationes. One Rogation Day sermon did not differ very much from others. Furthermore, the contents of these sermons fitted in very well with the general teachings of the Church concerning sin and penance. Repeated every year at the same time, they produced a cumulative effect on the ideas and mentalities of the audience.

The actual catastrophe sermons, on the other hand, were reactions to something that had already happened. When preached in the hectic situation of a natural disaster they were most certainly intended to have an immediate effect on their listeners. Immediate conversion and penance were required to placate the wrath of God. Surviving a cataclysm demanded something very close to a religious revival, or even a true and proper revival such as the flagellant movements.

The Setting of Catastrophe Sermons

The surviving catastrophe sermons offer us some important insights into the role of sermons in catastrophe situations. They let us know what kinds of disasters provided an occasion for preaching, and they also provide us with some information on where, when, and how catastrophe sermons were delivered. The sermons used in this study can be divided into three categories.

The first category consists of sermons that were preached before any other spiritual activities were undertaken. Their function was to inform the people what was going to happen and why. We have already mentioned such sermons, when dealing with the Parisian processions. It was said that a public sermon was held in the church of Saint-Étienne to inform the Parisians about the impending religious event.

A good example of such an informative public sermon is Nicolas de Gorran’s second sermon Ad impetrandam serenitatem. The thema of the sermon is taken from 3 Kings 18:44 ‘Prepare thy chariot and go down, lest the rain prevent thee.’ Nicolas starts by saying that these are the words of Elias to Achab, but they might as well be the words of Christ to the Church. He explains that these words stand for the three things that give prayer its efficiency, namely, unanimity, humility, and utility. The Church prepares its chariot when it comes together in an unanimous congregation.180 By this Nicolas presumably means Mass.

With the words go down, the Lord means that the Church must act with humility. This is done by forming a devote procession. The sermon closes with Nicolas’ exhortation that the people ought to prepare the chariot by coming unanimously together to go down by making a procession. All this is done ‘lest the rain prevent thee.’ The rain preventing them was of course the flood, which prevented people from living a normal life and caused all kinds of inconveniences.181 The length of the sermon is less than half of a modern printed page and does not provide many details. However, we can deduce from the sermon that it was preached, or was meant to be preached, to inform the audiences what had happened, and what kind of measures the Church was about to take. Most importantly, it informed them what was to be the role of the lay congregation in the upcoming liturgical activities. The people were informed about votive masses and processions.

Another rather curious sermon, if indeed it is a sermon at all, leads us to believe that, at least occasionally, a sermon was held before other measures to handle catastrophes comes from late medieval Sweden. It was probably written by a Brigettine monk from Vadstena Abbey.182 The sermon was written in answer to some major catastrophe that affected the whole kingdom. Unfortunately, the preacher does not tell us the exact nature of the catastrophe. However, judging from the context, the most plausible candidate is that it was a plague epidemic.

This curious sermon starts with God punishing the kingdom of Sweden because of the sins of its inhabitants. Then the preacher relates what penitential action ought to be taken to ensure that God’s punishment will cease. The preacher is merely stating the situation, that is, the imminence of the catastrophe, and then he proceeds to discuss what ought to be done.183 The bottom line is that in this particular case the role of the sermon was to say what would be done, and thus it certainly preceded processions, alms, masses, and other concrete forms of action.

If one puts proper catastrophe sermons aside and turns to Rogation Day sermons, one finds that, in many cases, they seem to have been delivered before the processions commenced. As seen above, many of these sermons placed a lot of emphasis on explaining the history and importance of such processions. If one considers the first Rogation Day sermon of Federico Pisano Visconti, which was certainly preached to a live audience (‘In letaniis ante ascensionem quam idem dominus fecit in uulgari’), one gets the impression that he is preaching about a procession that has not yet occurred.184

The second category consists of sermons, which were preached during the processions, either at the final destination, or in some station church along the road. The Salisbury processionale says that, once the procession had arrived at the stationary church, a mass was celebrated and in connection with it ‘fiat sermo ad populum, si placuerit.’185 These words do not allow us to conclude that sermons were always held in connection with processions, as a matter of fact; they seem to have been delivered only when the clergy felt it was needed. Furthermore, they do not reveal the custom outside Salisbury. Yet there is further evidence in the form of surviving catastrophe sermons that were originally delivered in connection with catastrophe processions.

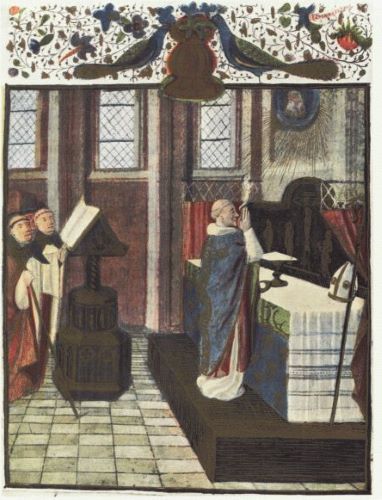

Eudes de Châteauroux, preached one such surviving catastrophe sermon probably in 1233, 1240 or 1242. It has come down to us in one single manuscript, in which the sermon carries the title in processione facta propter inundationem aquarum. As the title of the sermon indicates, it was delivered during a procession organised to stop flooding. The internal evidence confirms this. The concluding prayer mentions the relics of saint Genevieve and those of other saints that had been carried to the place where Eudes was preaching. This must either have been some station church during the procession or, more likely, the ultimate destination of the procession, that is, the cathedral of Notre-Dame.186 The latter possibility seems to be the most likely. In any case, the sermon was delivered well after the procession had started.

This is also the case with the early fourteenth-century sermon, In processione pro pluvia impetranda, from Dominican Giovanni Regina da Napoli. Again we can detect from the title given in the manuscript that the sermon was actually preached during a procession, not before. This is confirmed by the actual text of the sermon. Giovanni writes: ‘We are all gathered here to ask God to give us rain. To achieve this we have organised a procession and sung Mass.’187 Obviously, Giovanni was preaching in a church where the procession had ended. One might also speculate that the sermon was delivered right after the Mass following the procession.

The topics dealt with in the sermon also indicate that the procession and the Mass had already taken place. Giovanni does not say anything about the procession. We have seen that, in the case of the sermons delivered before the processions, it was common to reflect on the procession, its meaning, and its proper performance. Giovanni’s sermon is divided into three parts. The first one deals with the sinfulness of the congregation, the second is on the effects of prayer, whereas the third one contemplates the outcome of the process, when God has heard the prayers of the congregation.188 Hence the prayers of the individual members of the congregation that are the actual subject of the sermon. This is hardly surprising, since all the possible collective actions had already been taken.

The last category of catastrophe sermons consists of those that took place after the actual catastrophe and after the immediate activities in response. Such sermons are Eudes de Châteauroux’s Propter timorem terremotu and his Sermo quando timetur de terremotu. The latter one explicitly refers to an earthquake that had taken place recently (‘nuper’). Judging from their contents, both of these sermons were delivered a few days after the actual catastrophe.189 These sermons do not tell their audiences what they should do to save themselves and to bring the catastrophe to an end. They were merely explaining what had happened, and most of all why it had happened.

Votive Masses and Collective Prayers

Votive masses were another means of collective religious activity in times of acute danger. These were normally specific masses for a certain saint or for the Holy Virgin, but they could also designate masses in times of specific danger, such as natural disasters or wars.

The history of votive masses is nearly as old as the history of the Christian Church itself. Votive masses already existed in the early Church. The first written remnants of such masses are to be found in the Sacramentarium Gelasianum, most of which dates from the sixth century. The Old Gelasian sacramentary includes Masses in tribulatione, tempore mortalitatis, pro mortalitate animalium, ad pluviam postulandam, ad poscendum serenitatem, and post tempestatem et fulgura. The sacramentary thus includes most of the votive masses that were used during the late middle ages, and which are still part of the Missale Romanum.190

In medieval handbooks for the Mass, those masses already named in the Old Gelasian are nearly always included, whereas some others with a bearing on specific natural disasters were added. This is not the proper place to go through such sources extensively, but a few random sources will be given. At the time of Charlemagne, Alcuin supervised the revision of the sacramentary of Gallican Church. The new sacramentary included 44 votive masses, some of which are interesting from the point of view of this study: missa de quacunque tribulatione, missa pro peste animalium, missa ad pluviam postulandam, missa ad postulandam serenitatem, and missa ad repellendam tempestatem. In addition, the Archbishop Eudes de Cambrai (d. 1113) presented quite a few masses against natural disasters in his Expositio in canonem missae. Among these, we can, for instance, point to the mass Contra nimiam aeris siccitatem vel tempestatem and contrapestem.191