Portrait of Benjamin Franklin at 79 years of age, by Joseph Duplessis, 1785 / National Portrait Gallery, Washington

Curated and Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh / 01.30.2017

Brewminate Editor-in-Chief

Introduction

Left: Deborah Read Rogers Franklin, by Benjamin Wilson, 1758 / American Philosophical Society Museum

Right: William Franklin, by Mather Brown, 1790 / Collection of David A Schorsch and Eileen M. Smiles

Born in Boston on January 17, 1706, the tenth son of Josiah, a candle purveyor, and Abiah Folger. Educated at Boston Grammar School, Benjamin apprenticed with his father, and then his half-brother, Peter, a controversial printer in Boston. Young Franklin struck out on his own in 1723, eventually finding employment as a journeyman printer in Philadelphia. By 1730, he owned his own printing shop and had fathered a son, William, and married Deborah Read Rogers. Franklin’s newspaper The Pennsylvania Gazette, his Poor Richard’s Almanack, and work as an inventor and scientist propelled him to the front ranks of Philadelphia society and made him a well-known figure throughout the American provinces and England.

In 1757, at age fifty-one Franklin, began his career as a diplomat and statesman in London where he essentially remained until the outbreak of the American Revolution. When Franklin returned to Philadelphia in 1775, he served as a delegate to the Continental Congress, where he was instrumental in drafting the Declaration of Independence and the Articles of Confederation. Because of his international experience, Franklin was chosen as one the first ministers to France. In Paris Franklin reached his peak of fame, becoming the focal point for a cultural Franklin-mania among the French intellectual elite. Franklin ultimately helped negotiate a cessation of hostilities and a peace treaty that officially ended the Revolutionary War.

Even after his death in 1790, Franklin remained an American celebrity. Shortly after his death, his now famous autobiography was published in France and was followed two years later by British and American editions. Perhaps, the last, best summary should be the simple words of James Madison taken from his notes on Franklin: “I never passed half an hour in his company without hearing some observations or anecdote worth remembering.”

A Cause for Revolution

“Join or Die”

Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790). “Join, or Die.” Page 2. Woodcut from the Pennsylvania Gazette, Philadelphia, May 9, 1754. / Library of Congress

Benjamin Franklin published this woodcut in the Pennsylvania Gazette, which represents America as a snake severed into various provinces. Prior to the outbreak of the French and Indian War, Franklin hoped to persuade the American colonies to unite their governments to protect themselves from the French and their Native American allies under a plan later known as “The Albany Plan,” which was ultimately rejected. The image, the first to address unification of the colonies, would later be used as a symbol of the American Revolution with the motto: “Don’t Tread On Me.”

Magna Britannia

MAGNA Britannia, her Colonies REDUC’d. [Philadelphia, ca. 1766]. Photostat copy. / Rare Book & Special Collections Division, Library of Congress

This vivid allegorical cartoon, which illustrates the fatal effects on the empire that would result from taxing the colonies, was designed by Franklin in 1766. Franklin printed the image on cards that he distributed to Parliament during the debate over the repeal of the Stamp Act. This broadside carries a text that reads: “The Moral is, that the Colonies may be ruined, but that Britain would thereby be maimed.” Both the card and the broadside version, with the explanation and moral, are extremely rare.

Subverting the Stamp Act

No Stamped Paper To Be Had. [Philadelphia: Printed by Hall & Franklin, November 7, 1765]. / Rare Book & Special Collections Division, Library of Congress

On October 31, 1765, the publishers announced the suspension of the Pennsylvania Gazette in protest of the provisions of the Stamp Act, which required that newspapers be printed on imported, stamped paper that required payment of a duty. Between November 7 and December 26, Franklin’s partner David Hall issued news sheets on unstamped paper without a masthead, thus avoiding legal repercussions while satisfying the subscribers.

Franklin Supports the 1765 Stamp Act

An Act for granting and applying certain Stamp Duties… London: Mark Baskett, Printer to the King, 1765. Printed pamphlet. / Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

Benjamin Franklin, Pennsylvania agent and deputy postmaster general in North America, initially supported the Stamp Act of 1765, by which Parliament levied a new tax on British colonies. Although the tax would not raise much money, the British chancellor of the Exchequer Sir George Grenville wanted a declaration of Parliament’s sovereign right to tax the colonists. Franklin became an opponent when he learned of the fervent colonial opposition.

Stamp Act Repeal in 1766

Benjamin Franklin to Charles Thomson, September 27, 1766. Page 2. Manuscript letter. / Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

In this letter sent from London, Franklin thanks his old friend and Philadelphia neighbor for endorsing his conduct in regard to the repeal of the Stamp Act. Although Franklin, as Pennsylvania’s agent in London, had briefly supported the new tax on America, he quickly switched to opposition after hearing of the angry response in Pennsylvania. Franklin attributed America’s success in obtaining the repeal “to what the Profane would call Luck & the Pious Providence.”

Franklin and the King and Queen of France

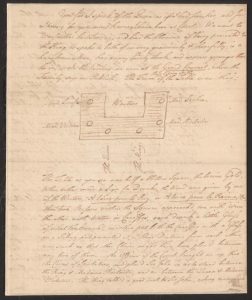

Benjamin Franklin to Mary Stevenson (1739–1795), September 14, 1767. Manuscript letter. / Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

Benjamin Franklin was visiting France in 1767 when he wrote this letter to Mary (Polly) Stevenson, the intellectually curious daughter of his British landlady, Margaret Stevenson (ca. 1706–1783), describing in words and a drawing his experience at a public supper with the French King Louis XV and Queen Marie, who spoke to Franklin “Very graciously and cheerfully.”

Break with Britain

“You are Now My Enemy”

Benjamin Franklin to William Strahan (1715–1785), July 5, 1775. Manuscript letter. / Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

Willliam Strahan, an English printer and publisher, who was Franklin’s friend and correspondent for many years, voted with the majority of Parliament to proclaim the Americans as rebels. Franklin drafted but never sent this well-publicized letter to Strahan to sever their friendship.

Response to the Hutchinson Affair

“Tract Relative to the Affair of Hutchinson’s Letters written by Dr. Franklin.” [1774]. Manuscript document. / Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

Benjamin Franklin wrote this tract after Alexander Wedderburn, British Solicitor-General, sharply attacked Franklin. Wedderburn asserted that Franklin was a “true incendiary” before the Privy Council on January 29, 1774, and accused him of being the “prime conductor” in the agitation against the British government largely for illegally obtaining copies of Massachusetts Governor Thomas Hutchinson’s letters filled with advice on how to subdue America by restricting its liberties. The tract was not published until after Franklin’s death.

Franklin before the Lords in Council

Robert Whitechurch (1814–ca. 1880), engraver. Franklin before the Lord’s Council, Whitehall Chapel, London, 1774. Hand-colored engraving, 1859. / Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress

This engraving captures the abusive hour-long attack waged by the British Solicitor-General Alexander Wedderburn against Franklin before the Privy Council in January 1774. Franklin remained silent throughout the attack. He would later write of the incident: “Spots of Dirt thrown upon my Character, I suffered while fresh remain; I . . . rely’d on the vulgar Adage, that they would all rub off when they were dry.”

“It is impossible we should think of Submission”

Benjamin Franklin to Lord Richard Howe (1726–1799), July 20, 1776. Page 2. Manuscript letter. / Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

Just days after the adoption of the Declaration of Independence by Congress, Benjamin Franklin wrote this stinging rebuke to the commander of British naval forces in North America and peace commissioner, Lord Richard Howe, who had offered pardons to American political leaders. The offer was rejected. Franklin replied that “It is impossible we should think of Submission to a Government” that has inflicted “atrocious Injuries” on Americans.

The Assumed Plan

Artist unknown. The Plan, or a Scene in the French Cabinet. [London: September 1779]. Etching. / Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress

This 1779 British political cartoon shows a laughing Franklin, at center, holding a copy of his “Plan” an invasion by French troops. In his other hand are strings connected to the noses of the French King and members of the French Court.

Continental Congress

City of Philadelphia

A plan of the city and environs of Philadelphia, survey’d by N. Scull and G. Heap. London: Will Faden, 1777. Engraved map. / Geography & Map Division, Library of Congress

Philadelphia, site of both Continental Congresses, was one of the most urban, advanced cities in America in the eighteenth century. Drawn by George Heap, a surveyor and city coroner of Philadelphia, and Nicolas Scull, Surveyor General of the Province of Pennsylvania and a friend to Franklin, this map shows streams, roads, and names of the landowners in the vicinity of Philadelphia. The bottom of the map contains an illustration of the State-House or Independence Hall, home of the Federal Convention of 1787.

Plan of the Confederation, 1775

Benjamin Franklin. Plan for a Confederation, July 21, 1775. Annotated document. / Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

Benjamin Franklin returned from London in May, 1775, and was quickly drafted as one of the Pennsylvania delegates to the second Continental Congress. Franklin’s plan for a government for a united colonial confederation was read in Congress on July 21, 1775, but was not acted upon at that time. Thomas Jefferson, a fellow delegate, annotated this copy of Franklin’s plan.

Benjamin Franklin Deliver a Petition

Petition of the Continental Congress to King George III, October 26, 1774. Page 2. Manuscript document in the hand of Timothy Matlack. / Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

Benjamin Franklin delivered this Petition of the Continental Congress, dated October 26, 1774 and signed by fifty-one delegates to the Congress, to Britain’s King George III. The petition, one of two copies sent to Franklin, stated the grievances of the American provinces and asked for the King’s help in seeking solutions.

The Edge of the Precipice

Charles Thomson (1729-1824) to Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790), November 1, 1774. Manuscript letter. / Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

Charles Thomson, secretary of the First Continental Congress, sent the petition of Congress to the British King, George III, with this cover letter to Benjamin Franklin, one of America’s agents in London. Thomson wrote that although there was still hope for peace, the colonies were on the “very edge of the precipice.” The petition, which outlined a peaceful redress of grievances, was summarily rejected by the British government.

To the Continental Congress

In Congress, July 19, 1776. Resolved, That it be earnestly recommended to the Convention of Pennsylvania, to hasten, with all possible Expedition, the March of the Associators into New-Jersey. Page 2. [Philadelphia: John Dunlap, 1776]. / Rare Book & Special Collections Division, Library of Congress

In anticipation of an imminent attack by enemy forces gathering on Staten Island, Congress had ordered the formation of a flying camp of militiamen from Delaware, Maryland, and Pennsylvania to defend New Jersey. Franklin was appointed to a Congressional committee charged with conferring with political and military authorities on the best means of defense. This broadside signed by Franklin as president of the Pennsylvania Convention, urges the provincial militia to march with expedition, disregarding any reports to the contrary.

Treaty of Paris

At the French Court

Anton Hohenstein (ca. 1823–?). Franklin’s Reception at the Court of France, 1778. Philadelphia: John Smith, n.d. Hand-colored lithograph. / Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress

In this idealized version of Franklin’s appearance at the Court in Versailles on March 20, 1778, King Louis XVI avowed the treaty of alliance between France and the United States by formally receiving the American commissioners. Franklin played the part of the rustic sage, as he shrewdly calculated the sophisticated courtiers would want to see him—wigless, bespectacled, and donning his “Quaker” suit of sober brown. He appeared again at the French court one year later as the U.S. Minister to France.

Negotiating the Treaty of Paris

Declaration of the Cessation of Arms and Treaty of Paris (in French), 1783. Page 2. Manuscript copy book. / Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

Benjamin Franklin was one of the American Commissioners in France who negotiated the Treaty of Paris with Great Britain ending the American Revolutionary War and securing the United States ownership of a vast territory between the Atlantic coast and the Mississippi River. The Declaration of the Cessation of Arms followed the Preliminary Treaty of Peace, which appears in Franklin’s copy book in French.

Constitutions of the Thirteen States of America

Louis-Alexandre, duc de La Rochefoucauld d’Enville, translator. Constitutions des Treize Etats-Unis de L’Amerique. Paris, Ph.-D. Pierres, 1783. / Rare Book & Special Collections Division, Library of Congress

Several weeks before the Treaty of Paris, Franklin arranged for the translation and publication of the thirteen state constitutions along with other founding documents and treaties of commerce and alliance. Believing the publication would be influential in supporting recognition of the new country by European powers, he had sumptuously bound copies presented to the French king and queen and all the French foreign ministers. The Great Seal of the United States, approved by Congress in June 1782, made its first printed appearance here. This copy is personally inscribed by Franklin to the translator.

Benjamin Franklin Parodied

Thomas Colley, engraver. A Political Concert; the vocal parts by 1. Miss America, 2. Franklin, 3. F-x, 4. Kepp-ll, 5. Mrs. Britannia, 6. Shelb-n, 7. Dun-i-g, 8. Benidick Rattle Snake. London: W. Richardson, February 18, 1783. Engraving. / Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress

This British cartoon appeared in London early in 1783 just after the preliminary treaty of peace ending the American Revolution became known in Great Britain. Allegorical figures of Britain and America support a pole crowned with a liberty cap. Benjamin Franklin leads a chorus that includes the Whig ministers Charles James Fox and Lord Shelburne, who made peace with the United States. The American traitor Benedict Arnold appears as a serpent, with a noose over his head.

The New Republic

“The Hypocrisy of this Country”

Benjamin Franklin to Anthony Benezet (1713–1784), August 22, 1772. Manuscript letter. / Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

Benjamin Franklin, despite having brought two Black slaves to England in 1757, became an eager supporter and correspondent of Anthony Benezet, the Philadelphia abolitionist and educator, who had written important anti-slavery pamphlets, books, and newspaper articles. As president of the Pennsylvania anti-slavery society, Franklin appealed for public support of a humanitarian plan to not only emancipate slaves, but to educate free blacks and their children and to facilitate their progress toward good citizenship.

Restoring Harmony

Benjamin Franklin. Draft speech, [June 11, 1787]. Manuscript document. / Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

When delegates became heated over the issue of proportional representation at the Federal Constitutional Convention in 1787 at Philadelphia, Benjamin Franklin urged “great Coolness and Temper,” telling the delegates “we are sent here to consult, not to contend, with each other.” As the eldest delegate at the Convention, Franklin acted on several occasions to restore harmony.

President of Pennsylvania

Bill of Sale, August 1787, signed by Benjamin Franklin. Manuscript document with seal. / Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

Benjamin Franklin was chosen president of Pennsylvania shortly after his 1785 return from France. The bulk of Franklin’s presidential duties included signing land grants, such as this 1787 bill of sale, and performing ceremonial functions.

A Copy of the Federal Constitution

Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790) to Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826), October 14, 1787. Manuscript letter. / Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

Benjamin Franklin enclosed a copy of the new federal constitution with this letter to Thomas Jefferson, the American minister to France, and thanked him for the receipt of a box of books.

“A Much More Respectable Bird”

Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790) to Sarah Bache (1743–1808), January 26, 1784. Manuscript letter. / Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

Benjamin Franklin criticized the new American hereditary military order of the Society of Cincinnati in this long letter to his daughter, Sarah Franklin Bache. He was particularly critical of the Society’s symbol, featuring “a Bald Eagle, but looks more like a Turk’ y. For in Truth, the Turk’y is in comparison a much more respectable Bird.”

The “growing strength” of the United States

Benjamin Franklin to George Washington, September 16, 1789. Page 2. Manuscript letter. / Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

In his eighty-fourth year, seven months before his death, an ailing Franklin writes to the nation’s first president George Washington: “For my own personal case, I should have died two years ago; but tho’ those years have been spent in excruciating pain, I am pleased that I have lived them since they brought me to see our present situation.”

Scientist and Inventor

Franklin with Apparatus

Edward Fisher (1730–ca. 1785), after Mason Chamberlin (d. 1787). Benjamin Franklin of Philadelphia, 1763. Mezzotint. / Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress

This portrait, which depicts Franklin as a learned scientist and inventor, was one of his favorites. Pictured on the left is the signal-bell apparatus Franklin devised to detect the presence of electrically-charged clouds. The bolt of lightning , seen through the open window, became an attribute closely identified with Franklin. At Franklin’s death French philosopher/scientist Jacques Turgot wrote: “He seized the lightning from the sky and the scepter from the hand of tyrants.”

The Franklin Stove

Benjamin Franklin. An Account of the New Invented Pennsylvanian Fire-Places. Page 2. Philadelphia: Printed and Sold by B. Franklin, 1744. / Rare Book & Special Collections Division, Library of Congress

Franklin wrote this description of the stove he had invented to promote sales of a model being manufactured by his friend Robert Grace. A series of partitioned iron plates permits a continuous supply of fresh warm air, separated from the smoke, to be distributed equally throughout the room. By controlling the airflow, less heat is lost, and much less wood is needed. Franklin’s stove became so popular in England and Europe that this essay was frequently reprinted and translated into several foreign languages.

Franklin’s Design for Bifocals

Benjamin Franklin to George Whatley (ca. 1709–1791), May 23, 1785. Letterpress manuscript. / Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

Benjamin Franklin is credited with the invention of bifocal glasses, which he sketched here for his friend George Whatley, a London merchant and pamphleteer. Franklin told Whately he found them particularly useful at dinner in France, where he could see the food he was eating and watch the facial expressions of those seated at the table with him, which helped interpret the words being said. He wrote: “I understand French better by the help of my Spectacles.”

Experiments in Electricity

Benjamin Franklin. Experiments and Observations on Electricity, made at Philadelphia in America, By Benjamin Franklin. Page 2. London, Printed for David Henry, 1769. / Rare Book & Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (37A)

In 1751, Peter Collinson, President of the Royal Society, arranged for the publication of a series of letters from Benjamin Franklin, 1747 to 1750, describing his experiments on electricity. Franklin demonstrated his new theory of positive and negative charges, suggested the electrical nature of lightning, and proposed a tall, grounded rod as a protection against lightning. These experiments established Franklin’s reputation as a scientist, and in 1753 he received the Copley Medal of the Royal Society for his contributions to the knowledge of lightning and electricity.

On Electricity

Benjamin Franklin. “Queries from Dr. Ingenhousz, with my Answers, B.F.”. Page 2. Page 3. Holograph report with annotations, [1777]. / Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

Benjamin Franklin’s formulation of a general theory of electrical “action” won him an international reputation in pure science in his own day. Writing to Dutch physician and scientist Jan Ingenhousz, Franklin responds to a number of his friend’s questions about electricity and the Leyden jar, an early form of electrical condenser. In this draft scientific report, it appears that Franklin wrote his answers first using dark ink, leaving room for the questions, which he wrote in red ink.

Franklin Explain the Effects of Lightning

Benjamin Franklin to Jan Ingenhousz, 1777. Manuscript essay. / Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

In this lengthy essay intended for his fellow scientist Jan Ingenhousz, Benjamin Franklin attempted to explain the effects of lightning on a church steeple in Cremona, Italy, by describing the effects of electricity on various metals. He based his hypothesis on other written accounts, and used this sketch of a tube of tin foil to aid in his explanation.

Mapping the Gulf Stream

Benjamin Franklin. “Maritime Observations and A Chart of the Gulph Stream.” in Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. Philadelphia: 1796. Engraved map. Geography & Map Division, Library of Congress

Although Spanish explorers had described the Gulf Stream, Franklin, fascinated by the fact that the sea journey from North America to England was shorter than the return trip, asked his cousin, Nantucket sea captain Timothy Folger, to map its dimensions and course. Franklin published this map and his directions for avoiding it in the Transactions of the American Philosophical Society in 1786. Systematic research, conducted by the U.S. Coast Survey, of the Gulf Stream did not occur until 1845.

Franklin Battles the Common Cold

Benjamin Franklin. “Hints concerning what is called Catching a Cold,” [1773]. Page 2. Manuscript document. Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

Despite his eminence in scientific circles, Benjamin Franklin remained concerned with the more practical applications of scientific study. This sheet entitled “Definition of a Cold” is one of a series bearing Franklin’s notes for a paper he intended to write on the subject. Exercise, bathing, and moderation in food and drink consumption were just some of his steps to avoid the common cold.

The Aurora Borealis

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790). “Suppositions and Conjectures on the Aurora Borealis,” [ca. December 1778]. Page 2. Page 3. Page 4. Manuscript essay. / Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

Benjamin Franklin’s interest in the mystery of the “Northern Lights” is said to have begun on his voyages across the North Atlantic to England. He ascribed the shifting lights to a concentration of electrical charges in the polar regions intensified by the snow and other moisture. He reasoned that this overcharging caused a release of electrical illumination into the air. In this essay, which he wrote in English and French, Franklin analyzed the causes of the Aurora Borealis. It was read at the French Académie des Sciences on April 14, 1779.

Franklin’s Armonica

L’Armonica: Lettera del Signor Beniamino Franklin al Padre Giambatista Beccaria, Regio Professore di Fisica nell’ Univ. di Torino. Page 2. [Milano?:1776?]. Rare Book & Special Collections Division, Library of Congress

Before leaving London in July 1762, Franklin wrote to the Italian philosopher Giambatista Beccaria. Not having anything new to report on their shared interest in electricity, Franklin described the improvements he had made to the musical glasses invented by Richard Puckeridge. By fitting a series of graduated glass discs on a spindle laid horizontal in a case and revolving the spindle by a foot treadle, Franklin could create bell-like tones by touching his wet fingers to the revolving glasses. Franklin’s armonica became popular in Europe, with Mozart and Beethoven composing music for it.

Printer and Writer

A Masterwork of Printing

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106–43 B.C.). M. T. Cicero’s Cato Major, or, his Discourse of Old-Age. Translated by James Logan. Philadelphia: Printed and Sold by B. Franklin, 1744. / Rare Book & Special Collections Division, Library of Congress

M.T. Cicero’s Cato Major, Franklin’s personal favorite from his press, is considered to be the finest example of the printing art in colonial America. Furthermore, this work by the Roman philosopher statesman Cicero is the first classic work translated and printed in North America.

In his “Printer to the Reader,” Franklin explains that he has printed this piece “in a large and fair Character, that those who begin to think on the Subject of old-age, . . . may not, in Reading by the Pain small Letters give the Eyes, feel the Pleasure of the Mind in the least allayed.”

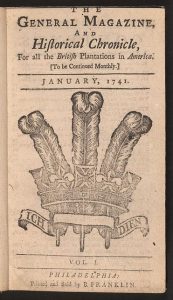

One of America’s First Magazines

The General Magazine, and Historical Chronicle, for all the British Plantations in America. Printed and Sold by B. Franklin, January 1741. Rare Book & Special Collections Division, Library of Congress

Franklin was the first to propose a monthly magazine for the American colonies. John Webb, whom Franklin had hoped to engage as editor, shared these plans with Franklin’s rival, Andrew Bradford, and those two decided to publish a magazine. Both printers issued their first number in February 1741. Bradford’s American Magazine, which may have beaten Franklin’s General Magazine by a few days, lasted only three issues, while Franklin’s magazine survived for six.

Promoting Useful Knowledge

[Benjamin Franklin]. A Proposal for Promoting Useful Knowledge among the British Plantations in America. Page 2. Philadelphia, 1743. Rare Book & Special Collections Division, Library of Congress

This rare broadsheet is the founding document of the American Philosophical Society, the oldest scientific society in America. Franklin proposed that Philadelphia members would exchange information and ideas regarding all fields of natural and applied science and correspond with members in other colonies and countries about practical matters to benefit their lives and improve mankind. Franklin served as society secretary during the early years, and later as president, when regular correspondence was established with the Royal Societies of London and Dublin. Franklin encouraged communication between the learned societies to continue even during the Revolution.

Benjamin Franklin’s Personal Liturgy

Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790). “Articles of Belief and Acts of Religion,” November 20, 1728. Manuscript document. / Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

Benjamin Franklin asserted in his autobiography that he had quickly tired of formal religious services, but that early in life he had written his own private articles of religious belief and a simple liturgy to be read on Sundays.

Ephrata Community Songbook

Ephrata Community. Die bittre Gute, oder Das Gesäng der einsamen Turtel-Taube… Page 2. / Manuscript hymnal, 1746. Music Division, Library of Congress

Founder of the German Seventh-Day Baptists Johann Conrad Beissel immigrated with the community to Ephrata, Pennsylvania, in 1732. Beissel served as the spiritual director of the group as well as its composer, devising his own system of composition. The group’s illuminated musical manuscripts were hand-lettered in Fraktur and are among the earliest original music composed in the British colonies. This illustrated hymnal was once in the possession of Benjamin Franklin. The rare second compilation of Beissel’s hymns was printed in roman type without music by Benjamin Franklin in 1732.

Printed Currency

Franklin and Hall [shillings]; Hall and Sellers [dollars]. Reverse of bill. Paper currency, various amounts and dates. / Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

Soon after establishing himself as an independent printer, Benjamin Franklin was awarded the “very profitable Jobb” of printing Pennsylvania bills of credit, partly because he had written and published a pamphlet on the need for paper currency in 1729. He was similarly employed by New Jersey and Delaware. Aware of the threat from counterfeiters, Franklin devised the use of mica in the paper and leaf imprints as ways to foil counterfeiters—both of these methods can be seen in these samples of currency printed by Franklin and his partner David Hall and later by the firm of Hall and William Sellers.

The Art of Making Money

The Art of Making Money Plenty in Every Man’s Pocket by Doctor Franklin. New York: P. Maverick, 1817. / Rare Book & Special Collections Division, Library of Congress

This humorous rendition of Franklin’s teaching that honesty, industry, and frugality are the keys to full pockets has continued to be a popular souvenir since it was first printed as a rebus in 1791. Here the familiar image of Franklin in a fur cap is one that introduced Franklin to France in 1777.

Franklin’s First Book

Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790). A Dissertation on Liberty and Necessity, Pleasure and Pain. London, 1725. Rare Book & Special Collections Division, Library of Congress

While working as a printer in London, Franklin published his first pamphlet at nineteen. In this metaphysical piece, a reply to William Wollaston’s The Religion of Nature Delineated, Franklin argued that if God was infinite wisdom and goodness, vice and virtue were empty distinctions. After distributing a few copies to his friends, Franklin became disenchanted with his reasoning and destroyed all remaining copies but one.

Poor Richard’s Almanack

[Benjamin Franklin]. Poor Richard, 1739. An Almanack for the Year of Christ 1739. Philadelphia: Printed and Sold by B. Franklin, 1738. Rare Book & Special Collections Division, Library of Congress

As a writer, Franklin was best known for the wit and wisdom he shared with the readers of his popular almanac, Poor Richard, under the pseudonym “Richard Saunders.” In his autobiography, Franklin notes that he began publishing his almanac in 1732 and continued for twenty-five years: “I endeavour’d to make it both entertaining and useful, and it accordingly came to be in such Demand that I reap’d considerable Profit from it, vending annually near ten Thousand.”

The Way to Wealth

Richard Saunders [Benjamin Franklin]. The Way to Wealth, and a Plan by which Every Man may pay his Taxes. Philadelphia: Printed by Daniel Humphreys, 1785. / Rare Book & Special Collections Division, Library of Congress

For his twenty-fifth almanac, for the year 1758, Franklin created a clever preface that reprised a number of proverbs from the almanac, framed as an event reported by Richard Saunders, in which Father Abraham advises a crowd attending a country auction that those seeking prosperity and virtue should diligently practice frugality and industry. Reprinted as Father Abraham’s Speech and The Way to Wealth, this piece has been translated into many languages and is the most extensively reprinted of all of Franklin’s writings. This is the first broadside edition, a popular format that allowed it to be tacked up on walls and distributed by clergy and gentry.

“Public Education for Our Youth”

Benjamin Franklin. “Observations Relative to the Intentions of the Original Founders of the Academy in Philadelphia,” June, 1789. Page 2. Manuscript essay. / Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

Throughout his life Benjamin Franklin had worked to educate the youth and citizens of Philadelphia. In this essay, he discussed his efforts to found a public subscription library in 1732, while seeking improvements in the governing of the Philadelphia Academy in 1789. When he died, Franklin left substantial bequests to fund public education in Philadelphia and Boston. By 1990, the remaining funds, totally more than seven million dollars, were distributed to schools and scholarship funds.

Franklin’s Autobiography

[Benjamin Franklin]. The Private Life of the Late Benjamin Franklin, LL.D. Late Minister Plenipotentiary from the United States of America to France, &c. London, Printed for J. Parsons, 1793. / Rare Book & Special Collections Division, Library of Congress

Franklin was sixty-five when he wrote the first part of his autobiography that focused on his early life to 1730. During the 1780s he added three briefer parts that advanced his story to his fiftieth year (1756) and revised the first part. In the summer of 1790, shortly after his death, extracts of Franklin’s memoirs appeared in two Philadelphia magazines, but the first book-length edition, based on a French translation, was published in 1791. The first English edition was published in London in 1793. Although William Temple Franklin’s 1818 edition became the standard version, John Bigelow’s 1858 edition was the first complete publication of all four parts taken directly from Franklin’s own manuscript.

Epitaph

A Letter to His Wife

Benjamin Franklin to Deborah Franklin (1705?–1774), January 6, 1773. Page 2. Manuscript letter. / Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

On the occasion of his birthday, January 6, 1773 (old-style, according to the Julian calendar) Benjamin Franklin reflects on earlier years with his wife, Deborah Read Rogers Franklin. Franklin recalls that “It seems but t’other Day since you and I were rank’d among the Boys and Girls, so swiftly does Time fly!” But Franklin still looked forward to “so great a Share of Health and Strength… as to render Life yet comfortable.”

Jefferson Eulogizes Benjamin Franklin

Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826) to William Smith (1727–1803), February 19, 1791. Page 2. Manuscript letter. / Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

After Benjamin Franklin’s death in 1790, Thomas Jefferson, then Secretary of State, wrote to the Reverend William Smith, who had been recruited by Franklin to head the new Philadelphia Academy, recalling that there was “more respect and veneration attached to the character of Doctor Franklin in France than to that of any other person in the same country.”

Philadelphia Accepts Legacy from Franklin

Report of the Committee “to whom was referrd the consideration of the Legacy left by Doct. B. Franklin to the Corporation,” June 18, 1790. Manuscript document. / Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

Benjamin Franklin, who like George Washington believed that public officials should work without a salary, stipulated in his will that his salary as president of the Executive Council of Pennsylvania should be given to the cities of Boston and Philadelphia. Trusts were established to manage the funds and to loan money at interest to apprentices seeking to establish their own business. Two trade schools, the Franklin Union in Boston and the Franklin Institute were later established with these funds and in 1990, as devised by Franklin, the funds, then worth more than seven million dollars, were distributed to schools and scholarship funds.

Praise for Franklin from James Madison

James Madison’s (1751–1836) notes on Benjamin Franklin. Manuscript document, post 1817. / Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

James Madison had high praise for Benjamin Franklin’s intellect and personality in his notes for a biographical memorandum on Franklin: “I never passed half an hour in his company without hearing some observation or anecdote worth remembering.”

The Senate Rejects Efforts to Honor Franklin

William Maclay’s diary April 23, 1790. Manuscript diary. / Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

After Benjamin Franklin’s death on April 17, 1790, the United States House of Representatives voted to wear black crepe as “a mark of the veneration due to his memory,” but the United States Senate, as reported by Pennsylvania Senator William Maclay, refused to wear “crape on their arms for a Month” and did not publicly acknowledge Franklin’s death until 1791.

Franklin’s Epitaph

Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790). Epitaph, 1728. Manuscript verse. / Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

A young Benjamin Franklin wrote this doggerel verse in 1728 to serve as his epitaph. Franklin, who loved to write humorous and satirical verses as well as essays, made copies of this verse for friends at various times in his life. This version, not in Franklin’s hand, was among the papers owned by Franklin’s grandson, William Temple Franklin.

Originally published by the Library of Congress, 06.17.2006, to the public domain.