To study the demographic composition of the Holy Land in the medieval era is to reject the myth of total transformation. It is instead to enter a realm where people remained even when empires fell.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: A Land at the Crossroads of History

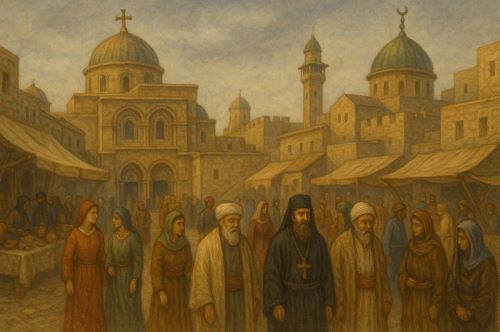

The medieval Holy Land was not merely a geographical designation; it was a crucible of empire, faith, ethnicity, and economic migration. To examine its demographic composition is to encounter the interwoven textures of political dominion and sacred geography. From the waning presence of Byzantine Christians in the early 600s to the shifting populations under the Ayyubids and Mamluks, the region that encompasses modern-day Israel, Palestine, and parts of Jordan and Lebanon bore witness to profound demographic transformation. Yet these shifts were not simple consequences of conquest. They arose from complex interplays among theological power structures, agrarian economies, regional migrations, and changing legal frameworks for coexistence.

Here I explore the demographic composition of the Holy Land across five critical periods: the Late Byzantine (early 600s), Early Islamic (638–1099), Crusader (1099–1291), Ayyubid (1187–1250), and Mamluk (1250–1516). The emphasis here is not only on numerical fluctuation but on the interpretive frameworks through which demography, ethnicity, and religion were lived and regulated. Each regime redrew not just borders but human possibility.

The Last Byzantine Dawn: Christianity and Continuity in the Early 600s

On the eve of the Muslim conquests, the Holy Land was firmly under the control of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire. It was a land profoundly Christian in identity, yet internally plural. Greek Orthodox Christianity dominated official life and ecclesiastical authority, but beneath the imperial liturgy existed a mosaic of linguistic and theological difference. Aramaic-speaking Christian communities, often Monophysite or Nestorian in doctrine, coexisted with the Chalcedonian mainstream.1 Jews, still a significant minority in Galilee and parts of Jerusalem despite Hadrianic expulsions, maintained urban and rural settlements.2

Although the Byzantines sought to maintain a Christian monopoly over religious power, they did not eliminate other groups entirely. Samaritan communities remained active, particularly in the hill country of Samaria, though their numbers declined following a series of revolts against imperial authority in the fifth and sixth centuries.3 Arab tribes such as the Ghassanids, Christian in faith and allied with Byzantium, occupied the frontier zones, marking early signs of the Arabization to come.4

Demographically, the region was largely rural, organized around villages and towns whose economies were tied to local agriculture, pilgrimage traffic, and urban trade. While population estimates are speculative, scholars generally agree that Christians formed a majority, though not a homogenous one. Religious identity overlapped with ethnic, linguistic, and class divisions. The Byzantine Holy Land was not a singular entity but a layered society on the edge of imperial reach.

The Early Islamic Conquests and the Gradual Arabization (638–1099)

The Arab-Muslim conquest of the Levant under the Rashidun Caliphate, beginning in 638 CE with the capture of Jerusalem, marks one of the most significant demographic turning points in the region’s history. Contrary to popular narratives of forced conversion or wholesale population displacement, the early Islamic rulers generally preserved the religious and ethnic composition of the conquered territories.5 Christians and Jews were granted dhimmi status, enabling them to retain their faith in exchange for paying the jizya tax and acknowledging Muslim political authority.6

Arabic rapidly became the lingua franca of administration and eventually daily life, but Arabization outpaced Islamization. For at least two centuries after the conquest, the majority population in the Holy Land likely remained Christian, albeit increasingly Arabic-speaking.7 Conversion to Islam, when it occurred, was gradual and often pragmatic, driven by economic or political incentives rather than coercion.8

The Umayyad period (661–750) saw investment in infrastructure and the consolidation of Muslim urban centers such as Ramla, founded explicitly as a new administrative capital. This contributed to urban demographic shifts, drawing populations from rural hinterlands into growing cities.9 The Abbasid era (750–969) continued these patterns but saw a relative decline in the region’s political prominence, as Baghdad and Egypt became more central to the Islamic world. Still, gradual demographic transformation continued. By the end of the Abbasid period, Muslims likely formed a slim majority in the region, but Christians, Jews, and Samaritans remained numerically significant.10

The Fatimid interlude (969–1099) introduced Shi’a governance, which complicated the religious landscape further. Periods of persecution, particularly under Caliph al-Hakim, disrupted Christian institutions, but the Fatimid period was not uniformly oppressive. Pilgrimage remained active, and Jerusalem was a shared city, an imperfect coexistence that would soon rupture.

Frankish Intrusions: The Crusader Period and the Reimagination of Space (1099–1291)

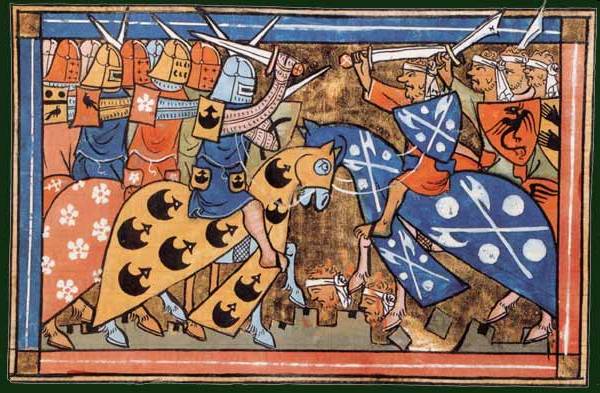

The First Crusade’s conquest of Jerusalem in 1099 marked a radical reordering not just of power but of demography. The siege and subsequent massacre of the city’s inhabitants decimated the Muslim and Jewish population of Jerusalem, though many Christians, particularly those of Eastern denominations, were also displaced or subordinated.11 The Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem imposed a European feudal structure upon an eastern society, privileging Western Christians while marginalizing local religious groups, including Greek Orthodox and Armenian Christians.12

Despite early purges, the Latin rulers could not maintain demographic dominance through force alone. By the mid-twelfth century, a more pragmatic policy emerged. Muslims were allowed to remain in the countryside as peasants, paying taxes and laboring on lands held by Frankish lords. In urban centers, Christian communities persisted, though often under Latin ecclesiastical oversight. The result was a curious demographic stratification: Frankish elites atop a rural Muslim peasantry, alongside indigenous Christians relegated to subordinate ecclesiastical roles.13

Demographic estimates suggest that Franks constituted no more than 15 percent of the population at any point, concentrated in fortified towns and coastal cities.14 Most of the countryside remained demographically Muslim and linguistically Arabic. Thus, while the Crusaders imposed new architectural and legal frameworks, they did not transform the population base. Their impact was cultural, not numerical.

The Ayyubid Restoration and Mamluk Consolidation (1187–1516)

Saladin’s reconquest of Jerusalem in 1187 initiated a demographic reversal. Muslims returned to the city, Latin Christians fled or were expelled, and Eastern Christian communities, particularly Orthodox and Armenian, were reinstated to positions of favor under Islamic rule.15 The Ayyubid period was marked by deliberate efforts to repopulate and Islamize urban centers. Jerusalem, long dominated by Latin architecture and clergy, became a renewed Islamic holy city, centered around the Haram al-Sharif.

Yet, this was not a wholesale reversal of Crusader demographics. Many Muslim and Christian peasants had remained in the countryside throughout Latin rule. What changed was the urban composition and administrative control. The Ayyubids, and later the Mamluks, emphasized patronage networks tied to religious identity, granting endowments (waqf) to Sunni institutions and incentivizing Sunni migration into key cities.16

The Mamluk period (1250–1516) deepened this demographic stratification. Mamluk policy centralized control through military elites and emphasized Islamic orthodoxy. Heterodox sects and non-Muslim communities faced tighter restrictions, though outright expulsion was rare. Jews, notably, experienced a relative renaissance in cities like Safed, which became a center of Kabbalistic learning in the late fifteenth century.17 Christians remained tolerated but constrained, their communities shrinking in urban centers even as they endured in more remote areas.

By the end of the Mamluk period, the Holy Land’s demographic composition had stabilized into a Muslim majority with Christian and Jewish minorities concentrated in specific regions. The rural population remained largely Muslim, while Christian enclaves survived in Galilee and along the coastal margins. The Mamluks did not pursue ethnic cleansing; instead, they curated a religious geography, favoring Islamic identity while preserving minority presence under hierarchical control.

Conclusion: Demography as Palimpsest, Not Tabula Rasa

Across nine centuries of conquest and counter-conquest, the Holy Land never became a blank slate. Each successive regime layered its own demographic preferences upon a complex and resilient population. Arabization did not erase Christianity. Islamization did not obliterate Judaism. The Crusaders imposed a new hierarchy without dismantling the existing social base. The Ayyubids and Mamluks restored Islamic control but retained pluralism within the boundaries of domination.

To study the demographic composition of the Holy Land in the medieval era is to reject the myth of total transformation. It is instead to enter a realm where people remained even when empires fell. Demography was shaped as much by economics, intermarriage, and survival as by religion or politics. The land was contested, yes, but it was also shared, imperfectly, painfully, and persistently.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Peter Brown, The Rise of Western Christendom: Triumph and Diversity, A.D. 200–1000 (Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013), 309.

- Oded Irshai, “The Christianization of the Roman Empire and the Persecution of the Jews,” in The Cambridge History of Judaism, Volume 4, ed. Steven T. Katz (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 123–25.

- Reinhard Pummer, The Samaritans: A Profile (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2016), 102–05.

- Robert G. Hoyland, Arabia and the Arabs: From the Bronze Age to the Coming of Islam (London: Routledge, 2001), 210.

- Fred Donner, The Early Islamic Conquests (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981), 269–71.

- Mark R. Cohen, Under Crescent and Cross: The Jews in the Middle Ages (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994), 35–37.

- Hugh Kennedy, The Great Arab Conquests: How the Spread of Islam Changed the World We Live In (Philadelphia: Da Capo, 2007), 145–48.

- Richard Bulliet, Conversion to Islam in the Medieval Period: An Essay in Quantitative History (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1979), 33–40.

- Gideon Avni, The Byzantine-Islamic Transition in Palestine: An Archaeological Approach (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 188–90.

- Michael Lecker, “Demographic Developments in Palestine Following the Arab Conquest,” Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 10 (1987): 49–60.

- Thomas Asbridge, The First Crusade: A New History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 301–03.

- Christopher MacEvitt, The Crusades and the Christian World of the East: Rough Tolerance (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008), 54–58.

- Ronnie Ellenblum, Frankish Rural Settlement in the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 213–18.

- Benjamin Z. Kedar, “The Subjected Muslims of the Frankish Levant,” in The Crusades: The Essential Readings, ed. Thomas Madden (Oxford: Blackwell, 2002), 233–34.

- Carole Hillenbrand, The Crusades: Islamic Perspectives (New York: Routledge, 2000), 397–99.

- Amalia Levanoni, “Religious Endowments (Waqf) and the Political Economy of the Ayyubid Period,” Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 29 (2004): 369–72.

- Jacob Rader Marcus, The Jew in the Medieval World (Cincinnati: Hebrew Union College Press, 1999), 280–82.

Bibliography

- Asbridge, Thomas. The First Crusade: A New History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Avni, Gideon. The Byzantine-Islamic Transition in Palestine: An Archaeological Approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Brown, Peter. The Rise of Western Christendom: Triumph and Diversity, A.D. 200–1000. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013.

- Bulliet, Richard. Conversion to Islam in the Medieval Period: An Essay in Quantitative History. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1979.

- Cohen, Mark R. Under Crescent and Cross: The Jews in the Middle Ages. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994.

- Donner, Fred. The Early Islamic Conquests. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981.

- Ellenblum, Ronnie. Frankish Rural Settlement in the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Hillenbrand, Carole. The Crusades: Islamic Perspectives. New York: Routledge, 2000.

- Hoyland, Robert G. Arabia and the Arabs: From the Bronze Age to the Coming of Islam. London: Routledge, 2001.

- Irshai, Oded. “The Christianization of the Roman Empire and the Persecution of the Jews.” In The Cambridge History of Judaism, Volume 4, edited by Steven T. Katz, 113–30. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- Kedar, Benjamin Z. “The Subjected Muslims of the Frankish Levant.” In The Crusades: The Essential Readings, edited by Thomas Madden, 233–41. Oxford: Blackwell, 2002.

- Kennedy, Hugh. The Great Arab Conquests: How the Spread of Islam Changed the World We Live In. Philadelphia: Da Capo, 2007.

- Lecker, Michael. “Demographic Developments in Palestine Following the Arab Conquest.” Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 10 (1987): 49–60.

- Levanoni, Amalia. “Religious Endowments (Waqf) and the Political Economy of the Ayyubid Period.” Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 29 (2004): 365–82.

- MacEvitt, Christopher. The Crusades and the Christian World of the East: Rough Tolerance. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008.

- Marcus, Jacob Rader. The Jew in the Medieval World. Cincinnati: Hebrew Union College Press, 1999.

- Pummer, Reinhard. The Samaritans: A Profile. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2016.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.25.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.