The investigation of coitus interruptus in the Middle Ages forces historians to navigate a terrain defined as much by silence and condemnation as by explicit record.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

In recent decades, historians of sexuality, medicine, and the body have increasingly challenged the once-widespread assumption that premodern societies lacked any notion or practice of fertility regulation. Rather than seeing contraception as a modern innovation, scholars have begun to probe how people in earlier periods, especially in the medieval world, might have harnessed behavioral, herbal, mechanical, or ritual techniques to influence reproduction. Among these, coitus interruptus (withdrawal) holds a special place: it is simple, concealable, and plausibly within lay awareness even in contexts of limited medical technology. Here I seek to recover how this practice (and its tolerances, prohibitions, and debates) was understood, deployed, and contested in the medieval West (and, by comparison, in parts of the medieval Islamic world).

The central question is: to what extent was coitus interruptus known, accepted, debated, or clandestinely practiced in the Middle Ages, and how did it sit within the broader constellation of medieval ideas about fertility, sin, health, and social constraint? To address this, one must navigate a difficult terrain of partial evidence, layered silences, moral discourse, and technical medical lore. Yet the effort is worthwhile: understanding withdrawal in the medieval imagination helps us rethink how medieval people conceived of sexual agency, bodily control, and the boundaries of pastoral and medical authority.

The historiographical stakes are significant. For much of the twentieth century, the dominant model in demographic and social history was a version of “contraceptive ignorance,” which assumed that until the modern era, people had no effective means or thought of limiting births except through abstinence, infanticide, or abortion. But scholars like John M. Riddle have challenged this view by mining medical and pharmacological texts for evidence of premodern contraceptive knowledge, suggesting instead a “hidden tradition” of fertility control.¹ More recently, articles and edited volumes on medieval sexuality, women’s health, and demography have advanced more nuanced, critical analyses of how and why medieval people may or may not have controlled fertility.² Nonetheless, many historians remain cautious: the fragmentary nature of the evidence invites overreach or excessive speculation, and the moral discourse of medieval Christian theologians often discourages direct acknowledgment of such practices.

Because of the nature of the sources, this essay necessarily proceeds by triangulation: reading between the lines of medical texts, penitentials, theological and canonical writings, vernacular lore, and demographic patterns. It is attentive to both what is said (explicit prohibitions, moral disapprobation, confessional queries) and what is left unsaid (silences, omissions, pragmatic counsel in medical handbooks). It also takes seriously the tensions between male-centered discourse and women’s embodied experience, recognizing that many fertility practices likely circulated in female social networks or among midwives, and therefore avoid explicit clerical records.

In what follows, I begin by clarifying the conceptual and theological frameworks in which coitus interruptus was understood in the medieval Christian world. I then turn to the medical and vernacular evidence for contraceptive practice or advice, probing how withdrawal might have been embedded within a broader repertoire of fertility regulation. After that, I examine the moral, theological, and pastoral debates around contriving sterility or preventing conception, focusing on how the “wasting of seed” was treated in canonical, penitential, and theological sources. I then place these practices in social and demographic context, exploring motivations (economic, familial, health) for limiting fertility and how coitus interruptus may have served (or failed as) a practical tool. Moving forward, I broaden the lens by comparing Christian medieval Europe with the medieval Islamic world and other cultural zones, showing contrasts in both acceptance and technique. Finally I reflect on the interpretive challenges posed by silence, bias, and the limits of inference, and suggests how a disciplined methodology might avoid speculative overreach. The conclusion draws together what we can reasonably conclude about the place of coitus interruptus in medieval culture, and offers directions for further research.

I do not claim to reconstruct a fully known “practice” of withdrawal in the Middle Ages (that would be impossible). But it does aim to map the conceptual, moral, and epistemic contours surrounding coitus interruptus, to show how medieval people thought about interventional refusal, bodily control, and the porous boundary between nature and contrivance. Such a reconstruction does more than illuminate an obscure corner of sexual history: it confronts how medieval actors navigated reproduction in an era without modern contraception, and offers a more capacious view of medieval sexual agency.

Conceptual and Theological Frameworks

Defining Coitus Interruptus

In modern usage, coitus interruptus refers to withdrawal of the penis prior to ejaculation in order to prevent semen from entering the vagina and thereby reduce the likelihood of conception.³ The practice, while physiologically simple, occupies a complex position in historical discourse because it simultaneously presupposes an understanding of semen’s generative role and elicits moral judgments about intentional interruption of the procreative act. In medieval sources, the practice was not consistently named, but it was widely recognized as a possible form of sexual misconduct. In Latin texts, it was sometimes described obliquely as semine effuso extra vas debitum, “seed spilled outside the proper vessel.”⁴ Such phrasing reveals not only awareness of the technique but also a theological valuation of its perceived violation of the divinely ordained purpose of intercourse.

Biblical Antecedent: The Case of Onan

The most influential biblical precedent was the story of Onan in Genesis 38, who, commanded to perform levirate marriage and raise offspring for his deceased brother, “spilled his seed on the ground” rather than impregnate Tamar.⁵ Patristic and medieval exegetes consistently interpreted this act not merely as disobedience to a specific commandment, but as a paradigmatic case of “wasting seed.”⁶ Augustine of Hippo condemned Onan’s act as both unnatural and sinful, placing it in the broader category of sexual acts that thwarted procreation.⁷ By the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, theologians like Peter Lombard and Thomas Aquinas canonized this interpretation within scholastic theology. Aquinas, for instance, argued that coitus interruptus fell under the peccata contra naturam (sins against nature) because it frustrated the divinely intended end of sexual activity to be generation.⁸

Canon Law and Penitential Tradition

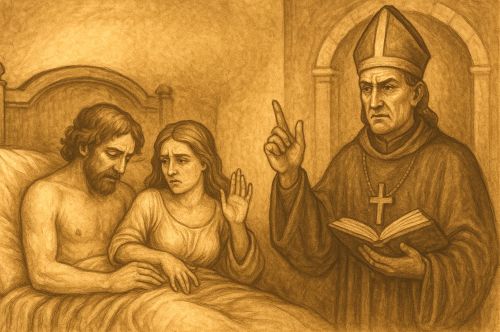

The penitential literature of the early Middle Ages, with its detailed catalogues of sins and penances, provides scattered but telling references to withdrawal. Burchard of Worms’ Corrector sive Medicus (early eleventh century) prescribed penances for men who “pollute themselves” by withdrawing or engaging in non-procreative intercourse.⁹ While the penitentials rarely employed precise physiological language, they reveal pastoral concern with acts deliberately performed “against conception.” These handbooks shaped clerical attitudes and guided confessors in interrogating penitents about sexual practices within marriage.

Gratian’s Decretum (c. 1140) and its later commentaries further systematized canonical prohibitions, drawing from both patristic authority and penitential precedent. The Decretists and later the Decretalists interpreted coitus interruptus as grounds for serious penance, though typically not equated with fornication or adultery.¹⁰ Instead, it occupied a distinct moral category: a sin internal to marital intercourse, corrupting the act’s natural end.

Scholastic Elaboration: Thomas Aquinas and Beyond

In the thirteenth century, scholastic theologians refined these categories. Aquinas distinguished between sins against chastity (such as fornication and adultery) and sins “contra naturam,” among which he included both homosexual acts and coitus interruptus.¹¹ He argued that the latter was especially grave because it involved the deliberate frustration of procreation, the telos of sexual union as ordained by natural law.¹² Later theologians, including Duns Scotus and William of Ockham, nuanced these discussions by debating intentionality, culpability, and circumstances, but they did not deviate from the broad consensus that withdrawal constituted a moral transgression.

Evidence for Practice: Medical and Vernacular Texts

Learned Medicine and Contraceptive Recipes

Beyond the pulpit and canon law, medical literature circulating in Latin and in translation provides striking, if fragmentary, evidence that contraception, including withdrawal, was part of the medieval reproductive landscape. The most prominent example is Avicenna’s Canon of Medicine, translated into Latin in the twelfth century and widely read in European universities.¹³ Avicenna enumerated various substances—plant-based pessaries, vaginal applications, and oral compounds, thought to impede conception or induce abortion.¹⁴ While withdrawal is not listed as a “recipe” in such texts, the juxtaposition of behavioral advice with pharmacological methods in the broader medical tradition suggests that educated physicians were not ignorant of its use. Moreover, later scholastic commentators sometimes referred to retractio or interruption of the sexual act in discussions of preventing conception, situating withdrawal within the medical lexicon of fertility regulation.¹⁵

Similar references appear in the Salernitan tradition. The Trotula, a composite text on women’s medicine assembled in southern Italy, offers remedies for regulating menstruation, treating infertility, and in some manuscripts, preventing conception.¹⁶ Although the Trotula does not explicitly describe coitus interruptus, its inclusion of contraceptive potions implies a cultural milieu in which methods of family limitation were known and circulated.¹⁷ Medical compendia in vernacular languages, such as Middle English translations of herbal manuals, also transmitted contraceptive lore.¹⁸ These texts make clear that medieval readers were exposed to a spectrum of reproductive interventions, even if withdrawal was rarely described outright.

Confessional Literature and Penitentials

If medical texts tend to list herbal or mechanical interventions, pastoral manuals and penitentials point more directly to the practice of withdrawal. For example, certain Anglo-Saxon penitentials admonish those who deliberately avoid conception by “spilling seed” and assign corresponding penances.¹⁹ The Carolingian-era penitentials of Halitgar and others contain similar injunctions.²⁰ Later manuals, designed to assist parish priests in hearing confession, warned against husbands who withdrew to avoid fatherhood.²¹ Such texts reveal that confessors expected to encounter penitents who had attempted withdrawal, proof that the practice was sufficiently common to require regulation.

A vivid late medieval example comes from the Florentine preacher Cherubino da Spoleto (d. 1484), who likened contraception to “cutting the branch that bears fruit.”²² Though he did not describe withdrawal in technical terms, his analogy condemned deliberate interruption of fertility. Such sermons, while rhetorical, presuppose a pastoral concern with practices recognizable to audiences, likely including coitus interruptus.

Vernacular Knowledge and Midwifery Lore

Women’s networks of knowledge also played a crucial role in transmitting contraceptive practices. While written records are scarce, owing to literacy barriers and clerical control of texts, some vernacular medical handbooks and recipe collections include remedies attributed to midwives.²³ John Riddle has argued that many seemingly “magical” charms or herbal prescriptions may in fact represent coded contraceptive knowledge, veiled in allegorical or non-explicit language to avoid censure.²⁴ In this context, withdrawal would have required no esoteric knowledge at all, making it one of the most accessible methods of limiting conception. Its very simplicity may explain why it left fewer textual traces compared to complex herbal formulas.

Silence and Implication

The relative paucity of explicit references to withdrawal in medical handbooks does not necessarily indicate ignorance. As P. P. A. Biller has noted, historians must reckon with “the silence of the sources,” recognizing that omission may result from assumed common knowledge rather than absence of practice.²⁵ Indeed, medical writers often focused on remedies requiring specialized expertise (herbal preparations, surgical interventions, regulated regimens of diet) precisely because these required codification. Withdrawal, needing only the cooperation of the male partner, could be practiced without textual mediation. Its appearance in confessional contexts, however, indicates that it was sufficiently widespread to merit pastoral concern.

Theological and Moral Debate

Sin and the Wasting of Seed

Among medieval theologians, the condemnation of withdrawal centered on the notion of the “wasting of seed.” Drawing on both biblical precedent and patristic authority, scholastics treated semen not as a mere bodily fluid but as the divinely endowed medium of human generation.²⁶ Augustine had already declared that marital intercourse was licit only when open to procreation, and that acts designed to avoid conception violated the order of creation.²⁷ For later theologians, withdrawal epitomized the deliberate frustration of God’s plan for sexuality. Peter Lombard’s Sentences categorized such acts as mortal sins, and his text became the foundation for subsequent scholastic commentary.²⁸

Thomas Aquinas elaborated further: in the Summa Theologiae, he argued that withdrawal was a sin against nature itself, ranking it alongside sodomy and bestiality as grave offenses.²⁹ Unlike fornication, which violated chastity, or adultery, which violated marital fidelity, withdrawal perverted the very end of intercourse by divorcing pleasure from procreation.³⁰ This hierarchical framing reinforced the pastoral insistence that intentional contraceptive acts, even within marriage, were more grievous than some extra-marital sins.

Confession and Pastoral Practice

Confessional manuals reveal how such theological judgments were translated into pastoral practice. Priests were instructed to inquire whether penitents had “corrupted the marriage act” by withdrawing or otherwise preventing conception.³¹ Penances could be severe, sometimes equal to those imposed for adultery.³² Yet variation abounded: some manuals distinguished between deliberate intent to avoid conception and accidental emission, indicating a pastoral sensitivity to circumstances.³³ These distinctions suggest that confessors recognized withdrawal as a real, recurring practice requiring nuanced guidance.

Popular Preaching and Moral Rhetoric

Beyond the learned schools, preachers disseminated theological judgments in vivid rhetoric. Bernardino of Siena, a celebrated fifteenth-century Franciscan preacher, castigated husbands who “strike at the root of the tree so that no fruit may grow,” equating contraceptive acts with homicide.³⁴ Such sermons brought the abstract condemnations of scholastic theology into the lived moral universe of ordinary Christians, shaping how laypeople understood the sinfulness of withdrawal. The vehemence of such preaching underscores the assumption that audiences would recognize and perhaps practice the condemned behavior.

Contrasts within the Christian Tradition

Despite the broad consensus, some dissenting voices or nuances appeared. Certain canonists questioned whether all instances of withdrawal merited the same severity of judgment, particularly in cases where health or economic necessity might motivate fertility limitation.³⁵ Others admitted that intent mattered: if intercourse was completed but ejaculation occurred too late to ensure conception, culpability might be mitigated.³⁶ These debates reflect the pastoral struggle to reconcile rigid theological categories with the complexities of lived marital life.

Social and Demographic Context

Motivations for Fertility Control

To understand why withdrawal might have been practiced despite moral prohibitions, one must situate it within the social and demographic realities of medieval Europe. Families faced chronic economic pressures, recurrent famine, epidemic disease, and high infant mortality.³⁷ For peasants and artisans alike, the ability to regulate family size could mean the difference between survival and destitution. In urban centers, where guild membership and inheritance often limited opportunities, too many children strained household resources.³⁸ These conditions created incentives for couples to seek practical ways of limiting births.

Medical and pastoral sources, though hostile, implicitly acknowledge these pressures. Theologians condemned withdrawal precisely because it was tempting: an accessible, low-cost, and discreet method of regulating fertility.³⁹ For many households, the alternative of abstinence was unrealistic, while abortion carried greater dangers and moral stigma. Withdrawal, by contrast, required no special knowledge or materials, only cooperation between partners.

Demographic Indicators

While direct evidence of contraceptive practice is scarce, some demographic studies suggest patterns consistent with deliberate fertility limitation. Richard Smith has argued that variations in family size and spacing in late medieval England may indicate strategies of birth control beyond delayed marriage.⁴⁰ Similarly, in parts of Italy and southern France, records of notarial contracts and household structures suggest an awareness of limiting offspring.⁴¹ Though one must be cautious, demography cannot conclusively prove practice, the circumstantial evidence aligns with the pastoral concern reflected in confessional literature.

Gendered Dynamics

The practice of withdrawal also illuminates gender relations within marriage. Because it placed control in the hands of the husband, it reflected and reinforced patriarchal authority.⁴² Women may have encouraged or resisted its use, but ultimately the act required male decision at the crucial moment. This imbalance contrasts with herbal contraceptives, which may have circulated more readily among women’s networks and placed agency in their hands.⁴³ The prevalence of sermons and confessional inquiries directed at men underscores the perception that withdrawal was primarily a male responsibility, even as its consequences directly affected women’s lives.

Risks and Limitations

Coitus interruptus was, of course, unreliable as a contraceptive method. Medieval couples would not have known the modern biology of pre-ejaculate fluid, but they could observe that the practice sometimes failed.⁴⁴ Theological writers exploited this unreliability to argue that divine providence would thwart human attempts at controlling fertility.⁴⁵ Yet its persistence in confessional discourse suggests that many couples nevertheless relied upon it. For them, the risk of occasional failure may have been outweighed by the benefits of reducing the probability of conception.

Comparative Perspectives: Christian Europe and the Islamic World

Islamic Jurisprudence on Withdrawal (‘Azl)

In the medieval Islamic world, withdrawal (‘azl) was openly discussed by jurists, physicians, and theologians. Unlike the near-universal condemnation in Latin Christendom, Islamic jurisprudence revealed a more pragmatic stance. The Hadith literature records debates about whether ‘azl was permissible, with some traditions reporting that the Prophet Muhammad’s companions practiced it and that the Prophet did not forbid it outright.⁴⁶ Jurists across the major Sunni schools generally permitted withdrawal with the wife’s consent, though they debated its ethical desirability.⁴⁷

This relative permissiveness reflected Islamic law’s concern with marital rights and intentions. If both partners agreed, and if withdrawal was not used to evade procreation entirely, it could be tolerated.⁴⁸ Such positions highlight a striking divergence from medieval Christian theology, in which any deliberate interruption of procreation was classed as a sin against nature.

Medical Literature in Arabic Traditions

Arabic medical texts paralleled jurisprudential openness. Writers like Avicenna and al-Razi mentioned withdrawal among methods of fertility control, alongside pessaries and herbal concoctions.⁴⁹ These references suggest that the practice was not only acknowledged but incorporated into the spectrum of legitimate medical advice. Translation of these works into Latin brought knowledge of withdrawal into European learned culture, though Christian theologians reframed it negatively.⁵⁰

Jewish Perspectives

Medieval Jewish authorities, particularly within rabbinic responsa literature, also addressed coitus interruptus. Influenced by biblical injunctions and Talmudic precedent, most authorities condemned the deliberate wasting of seed, echoing the Onan story.⁵¹ Yet practical debates emerged around specific circumstances, such as protecting a wife’s health, in which some leniency was considered.⁵² Here again, the evidence reveals a spectrum of toleration shaped by communal and contextual concerns.

Cross-Cultural Implications

Placing Christian Europe in comparative perspective underscores the intensity of its moral condemnation. Whereas Islamic and, in limited cases, Jewish traditions permitted withdrawal under negotiated conditions, Latin Christendom consistently classified it as gravely sinful. This divergence highlights how theology, rather than medical knowledge, drove the strict prohibition in the Christian West. It also suggests that cross-cultural exchanges in medicine did not erase fundamental differences in moral reasoning about sexuality.

Methodological Challenges

The Problem of Silence

One of the greatest challenges in reconstructing the history of coitus interruptus in the Middle Ages is the scarcity of explicit references. Unlike herbal recipes or mechanical devices, withdrawal required no material culture to leave behind.⁵³ Consequently, it appears mainly in the negative spaces of texts: penitential condemnations, theological prohibitions, or rhetorical preaching. Historians must resist the temptation to read silence as ignorance. As Peter Biller has emphasized, omission often signals assumed familiarity rather than absence of practice.⁵⁴

Bias of Surviving Sources

The sources that do survive are overwhelmingly clerical, theological, or medical, shaped by male elites whose priorities often diverged from the lived realities of lay couples. Women’s voices are largely absent, except indirectly through midwifery lore or vernacular recipe books.⁵⁵ The normative judgments of clerics and physicians obscure how couples themselves understood or experienced withdrawal. This imbalance challenges historians to read against the grain, attentive to what is suppressed as much as what is articulated.

Risks of Overinterpretation

Scholars such as John Riddle have argued for a widespread “hidden tradition” of contraception in the medieval West, preserved in recipe literature and women’s knowledge networks.⁵⁶ While provocative, this thesis has been criticized for overextending thin evidence and for reading every ambiguous reference as contraceptive in intent.⁵⁷ A disciplined methodology must acknowledge both the likelihood of widespread practice and the limits of textual proof. Otherwise, historiography risks collapsing into speculation.

Interdisciplinary Approaches

To navigate these problems, historians increasingly adopt interdisciplinary methods, drawing on demography, anthropology, and the history of medicine. Household structures, inheritance patterns, and mortality rates provide circumstantial evidence for fertility control.⁵⁸ Comparative anthropology reminds us that withdrawal is a nearly universal practice, observed across cultures and epochs, which increases the probability of its medieval use.⁵⁹ The task is not to “prove” prevalence beyond doubt but to reconstruct plausible contexts, mechanisms, and meanings within the available evidence.

Conclusion

The investigation of coitus interruptus in the Middle Ages forces historians to navigate a terrain defined as much by silence and condemnation as by explicit record. From Augustine’s forceful denunciations to Aquinas’s scholastic classification of withdrawal as a peccatum contra naturam, the theological consensus was unwavering: to deliberately thwart procreation was to sin against both divine command and natural law.⁶⁰ Penitentials, canon law, and pastoral sermons reinforced this view, embedding it deeply in the moral vocabulary of Latin Christendom. Yet the very persistence of these condemnations across centuries betrays the reality they sought to suppress. A sin repeated is a sin practiced, and coitus interruptus was evidently common enough to haunt the conscience of confessors and preachers alike.⁶¹

Outside the ecclesiastical lens, the medical and vernacular traditions complicate the picture. Avicenna, al-Rāzī, and the Trotula testify to a medical culture that recognized contraception as both conceivable and achievable, whether through herbs, pessaries, or behavioral regulation.⁶² Midwives and women’s oral networks likely disseminated practical knowledge, even if such voices remain largely invisible in the surviving record. The simplicity of withdrawal ensured that it required no textual prescription, yet confessional literature confirms that it was practiced, precisely because it needed no physician.

The demographic and social context provides powerful incentives for its use. Households burdened by poverty, women endangered by repeated pregnancies, and couples anxious about dowries or inheritance had practical reasons to limit births.⁶³ Withdrawal, immediate and costless, offered an obvious strategy, one that may have been practiced quietly across Europe despite the weight of ecclesiastical prohibitions. Comparative perspectives sharpen this contrast: in Islam, ʿazl was broadly tolerated with conditions of consent, while Jewish halakhic authorities sometimes allowed withdrawal to preserve a woman’s health.⁶⁴ The rigidity of Latin Christianity thus appears not inevitable, but historically contingent, reflecting particular theological priorities rather than universal moral intuitions.

At the same time, methodological humility is necessary. The evidence for coitus interruptus is largely indirect, mediated through the condemnations of clerics and theologians. Unlike herbal abortifacients or contraceptive devices, it leaves no archaeological trace and little textual detail. Historians must balance recognition of its likely use with caution against projecting modern contraceptive cultures backward too confidently. As Michael Sheehan cautioned, the lived experience of medieval marriage often eludes the categories of law and doctrine.⁶⁵

What emerges, then, is a nuanced portrait. Coitus interruptus was widely condemned yet persistently practiced, hidden in the interstices of pastoral anxiety, household negotiation, and demographic necessity. It belonged to what John Riddle has called the “shadow tradition” of fertility control, a repertoire of practices never fully recorded but never entirely absent.⁶⁶ To trace its outlines is to glimpse the tensions between doctrine and desire, sin and survival, that structured medieval life.

Far from being an obscure footnote, the history of withdrawal illuminates broader themes in medieval society: the interplay of theology and practice, the gendered politics of reproduction, and the comparative contingency of moral frameworks across cultures. It reminds us that medieval men and women were neither wholly passive before nature nor wholly obedient to doctrine. They navigated the uncertainties of fertility with the tools (pharmacological, behavioral, and spiritual) available to them. To study coitus interruptus in the Middle Ages is therefore to recover an essential dimension of human agency: the perennial negotiation between body, belief, and necessity.

Appendix

Footnotes

- John M. Riddle, Contraception and Abortion from the Ancient World to the Renaissance (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1992), 3–7.

- Danielle Jacquart and Claude Thomasset, Sexuality and Medicine in the Middle Ages (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988), 121–24.

- Angus McLaren, A History of Contraception: From Antiquity to the Present Day (Oxford: Blackwell, 1990), 22–24.

- Pierre J. Payer, Sex and the Penitentials: The Development of a Sexual Code, 550–1150 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1984), 93.

- Genesis 38:9.

- John T. Noonan Jr., Contraception: A History of Its Treatment by the Catholic Theologians and Canonists (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1965), 44–46.

- Augustine, De coniugiis adulterinis II.12, in Noonan, Contraception, 47–48.

- Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae II–II, q.154, a.11.

- Burchard of Worms, Corrector sive Medicus, in Corpus Christianorum, Continuatio Mediaeualis 21, ed. D. Wasserschleben (Leipzig, 1851), 392.

- Noonan, Contraception, 149–56.

- Aquinas, Summa Theologiae II–II, q.154, a.11.

- Ibid.

- Avicenna, Canon of Medicine, trans. Gerard of Cremona (12th c.); Nancy Siraisi, Avicenna in Renaissance Italy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987), 23–27.

- Riddle, Contraception and Abortion, 96–102.

- Jacquart and Thomasset, Sexuality and Medicine, 127–29.

- Monica H. Green, ed. and trans., The Trotula (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001), 103–07.

- Green, The Trotula, 118–20.

- Worcester Cathedral Library and Archive, “A Middle English Herbal” (2018).

- Payer, Sex and the Penitentials, 92–94.

- James A. Brundage, Law, Sex, and Christian Society in Medieval Europe (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), 227–29.

- Pierre J. Payer, The Bridling of Desire (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1993), 81–83.

- P. P. A. Biller, “Birth Control in the West in the Thirteenth and Early Fourteenth Centuries,” Past & Present, no. 94 (1982): 25.

- Monica H. Green, Making Women’s Medicine Masculine (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 167–72.

- Riddle, Contraception and Abortion, 131–34.

- Biller, “Birth Control in the West,” 5.

- Brundage, Law, Sex, and Christian Society, 224–27.

- Augustine, De bono coniugali 4.4, in The Works of Saint Augustine, ed. John E. Rotelle, trans. Ray Kearney (Hyde Park, N.Y.: New City Press, 1999), 33.

- Peter Lombard, Sententiae IV, dist. 31, c.1, in Magistri Petri Lombardi Sententiae in IV Libris Distinctae, ed. Ignatius C. Brady (Grottaferrata: Collegium S. Bonaventurae, 1971).

- Aquinas, Summa Theologiae II–II, q.154, a.11.

- Ibid.

- Payer, The Bridling of Desire, 84–85.

- Payer, Sex and the Penitentials, 95.

- Brundage, Law, Sex, and Christian Society, 231–32.

- Bernardino of Siena, Prediche volgari, ed. C. Cannarozzi (Florence: Olschki, 1940), 112–13.

- Noonan, Contraception, 157–61.

- Ibid., 164–66.

- Barbara A. Hanawalt, The Ties That Bound: Peasant Families in Medieval England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), 77–82.

- David Herlihy, Medieval Households (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1985), 123–27.

- Brundage, Law, Sex, and Christian Society, 234–35.

- Smith, Richard M., “Fertility, Economy, and Household Formation in England over Three Centuries,” Population and Development Review, 7:4 (1981).

- Christiane Klapisch-Zuber, Women, Family, and Ritual in Renaissance Italy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985), 119–23.

- Jacqueline Murray, “Gendered Souls in Sexed Bodies,” in Handling Sin: Confession in the Middle Ages, ed. Peter Biller and A. J. Minnis (York: York Medieval Press, 1998), 97–99.

- Monica H. Green, Women’s Healthcare in the Medieval West (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2000), 201–04.

- McLaren, A History of Contraception, 27.

- Aquinas, Summa Theologiae II–II, q.154, a.11.

- Sahih Muslim 1438, in The Translation of the Meanings of Sahih Muslim, trans. Abdul Hamid Siddiqi (Lahore: Sh. Muhammad Ashraf, 1976), 483–84.

- Fazlur Rahman, Health and Medicine in the Islamic Tradition (New York: Crossroad, 1987), 56–59.

- Michael Dols, Medieval Islamic Medicine (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1984), 141–43.

- Avicenna, Canon of Medicine, bk. III, fen. 20; al-Razi, Kitab al-Hawi (Hyderabad: Dairat al-Ma’arif, 1955), 212–14.

- Siraisi, Avicenna in Renaissance Italy, 31–33.

- Noonan, Contraception, 90–95.

- Judith Hauptman, Rereading the Rabbis: A Woman’s Voice (Boulder: Westview Press, 1998), 144–47.

- Brundage, Law, Sex, and Christian Society, 233.

- Biller, “Birth Control in the West,” 5.

- Green, Making Women’s Medicine Masculine, 171–75.

- Riddle, Contraception and Abortion, 125–34.

- Monica H. Green, “Flowers, Poisons, and Men: Menstruation in Medieval Texts,” Speculum 84, no. 4 (2009): 944–46.

- Smith, “Fertility, Economy, and Household Formation in Medieval England,” 31–32.

- McLaren, A History of Contraception, 15.

- Augustine, De coniugiis adulterinis II.12; Aquinas, Summa Theologiae II–II, q.154, a.11.

- Payer, Sex and the Penitentials, 92–95.

- Avicenna, Canon of Medicine; al-Rāzī, Kitab al-Hawi; Green, The Trotula, 118–20.

- Hanawalt, The Ties That Bound, 77–82.

- Rahman, Health and Medicine in the Islamic Tradition, 56–59; Hauptman, Rereading the Rabbis, 144–47.

- Michael Sheehan, Marriage, Family, and Law in Medieval Europe (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1996), 103–05.

- Riddle, Contraception and Abortion, 125–34.

Bibliography

- Avicenna. Canon of Medicine. Translated by Gerard of Cremona, 12th c.

- Bernardino of Siena. Prediche volgari. Edited by C. Cannarozzi. Florence: Olschki, 1940.

- Biller, P. P. A. “Birth Control in the West in the Thirteenth and Early Fourteenth Centuries.” Past & Present, no. 94 (1982): 3–26.

- Brundage, James A. Law, Sex, and Christian Society in Medieval Europe. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987.

- Worcester Cathedral Library and Archive. “A Middle English Herbal.” (July 30, 2018). https://worcestercathedrallibrary.wordpress.com/2018/07/30/a-middle-english-herbal/.

- Green, Monica H. Making Women’s Medicine Masculine: The Rise of Male Authority in Pre-Modern Gynaecology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- ———. Women’s Healthcare in the Medieval West. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2000.

- ———, ed. and trans. The Trotula: An English Translation of the Medieval Compendium of Women’s Medicine. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001.

- Hanawalt, Barbara A. The Ties That Bound: Peasant Families in Medieval England. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986.

- Hauptman, Judith. Rereading the Rabbis: A Woman’s Voice. Boulder: Westview Press, 1998.

- Herlihy, David. Medieval Households. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1985.

- Jacquart, Danielle, and Claude Thomasset. Sexuality and Medicine in the Middle Ages. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988.

- Klapisch-Zuber, Christiane. Women, Family, and Ritual in Renaissance Italy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985.

- McLaren, Angus. A History of Contraception: From Antiquity to the Present Day. Oxford: Blackwell, 1990.

- Noonan, John T. Jr. Contraception: A History of Its Treatment by the Catholic Theologians and Canonists. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1965.

- Payer, Pierre J. Sex and the Penitentials: The Development of a Sexual Code, 550–1150. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1984.

- ———. The Bridling of Desire: Views of Sex in the Later Middle Ages. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1993.

- Rahman, Fazlur. Health and Medicine in the Islamic Tradition. New York: Crossroad, 1987.

- Razi, al-. Kitab al-Hawi. Translated as Comprehensive Book on Medicine. Hyderabad: Dairat al-Ma’arif, 1955.

- Riddle, John M. Contraception and Abortion from the Ancient World to the Renaissance. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1992.

- Sahih Muslim. In The Translation of the Meanings of Sahih Muslim. Translated by Abdul Hamid Siddiqi. Lahore: Sh. Muhammad Ashraf, 1976.

- Sheehan, Michael. Marriage, Family, and Law in Medieval Europe. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1996.

- Siraisi, Nancy. Avicenna in Renaissance Italy: The Canon and Medical Teaching in Italian Universities after 1500. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987.

- Smith, Richard M. “Fertility, Economy, and Household Formation in England over Three Centuries.” Population and Development Review, 7:4 (1981): 595-622.

Originally published by Brewminate, 09.30.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.