Viewed within its historical moment, The Great Gatsby reveals how the dream of equality and opportunity had already collapsed beneath the weight of corporate capitalism.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

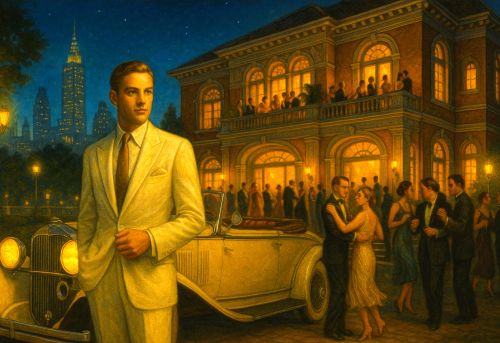

When F. Scott Fitzgerald published The Great Gatsby in 1925, the United States was basking in the glow of what seemed like limitless prosperity. The “Roaring Twenties” were defined by technological innovation, easy credit, and the dizzying expansion of consumer culture. Mass advertising transformed wants into perceived needs, and corporations marketed the promise of happiness through commodities. Against this glittering backdrop, Fitzgerald’s novel emerged as both a portrait and a critique of the age, a literary mirror held up to a society intoxicated by its own reflection.

At its core, The Great Gatsby interrogates the corruption of the American Dream, that once-idealistic belief in self-made success and moral integrity that had guided national identity since the republic’s founding. In Fitzgerald’s 1920s, that dream has been hollowed out, replaced by the pursuit of wealth, status, and fleeting pleasure. Jay Gatsby’s rise from obscurity to opulence seems, at first glance, to embody the dream of reinvention. Yet the moral vacuum of his world (one of bootleg fortunes, lavish parties, and careless aristocrats) reveals the rot beneath the glitter. Fitzgerald’s critique, rooted in the actual historical realities of his time, exposes a society where materialism masquerades as meaning and where the promise of equality dissolves into class entrenchment.

What follows examines The Great Gatsby within its true historical context: the economic boom and consumer revolution of the 1920s, the rigid hierarchies of old and new money, and the pervasive sense of moral disorientation following World War I. It will analyze how Fitzgerald transforms these realities into literary symbols (the green light, the valley of ashes, the geography of East and West Egg) to portray the American Dream as an illusion corrupted by greed and desire. Through this lens, the novel stands not merely as a personal tragedy but as a national elegy, mourning a dream sold for profit and a generation lost to its own consumption.

Historical Context: The 1920s United States

The world of The Great Gatsby could not have existed apart from the economic and cultural upheavals of the 1920s. After World War I, the United States experienced an unprecedented surge in industrial output and consumer spending. Between 1922 and 1929, the nation’s gross national product grew by nearly 40 percent, fueled by mass production, technological innovation, and expanding urban markets.1 Automobiles, radios, and household appliances became ubiquitous symbols of modernity and success. Advertising, an industry that had matured during the war, now promised not only utility but happiness, suggesting that one’s identity could be purchased. By 1929, American businesses were spending more than three billion dollars annually on advertising, an astonishing figure that reflected how deeply consumption had been woven into the fabric of everyday life.2

This transformation also reshaped social values. Historian Warren Susman described the 1920s as a shift from a “culture of character” to a “culture of personality,” where appearance, charm, and consumer display replaced moral virtue as measures of worth.3 The prosperity of the decade widened class divisions even as it seemed to dissolve them. The old-money elite of places like East Egg clung to inherited privilege, while self-made entrepreneurs, often enriched through new industries or illicit enterprises, constructed their own fantasies of grandeur. Prohibition, enacted in 1920, intensified this divide by criminalizing alcohol and inadvertently creating a vast underground economy that rewarded cunning over conscience. Figures like Jay Gatsby, whose wealth derives from shadowy ventures, reflected a real social phenomenon: the rise of men who appeared to embody the American Dream but were tainted by the very system that made them rich.4

The spiritual costs of this economic triumph were evident. Urbanization and modern technology fractured traditional communities, while a pervasive sense of moral drift haunted the age. Religious attendance declined, and public discourse increasingly celebrated pleasure and novelty over restraint and duty.5 Advertising magnified these trends by conflating virtue with consumption, persuading Americans that buying the right car, home, or wardrobe could restore meaning in a rapidly changing world.6 In this way, the 1920s were not merely prosperous; they were performative. The decade’s vitality concealed an anxiety about authenticity that Fitzgerald would crystallize in The Great Gatsby, where glittering surfaces mask emptiness and dreams are defined by what can be bought.

Literary Analysis: The Great Gatsby and the Corrupted American Dream

Jay Gatsby stands at the heart of Fitzgerald’s moral diagnosis of the 1920s. To his contemporaries, Gatsby represents the promise of reinvention, a man who rose from poverty to fabulous wealth, a self-made figure of charisma and mystery. Yet Fitzgerald renders this ascent as tragic rather than triumphant. Gatsby’s fortune, born of dubious enterprises, embodies the decade’s worship of wealth stripped of moral foundation.7 His dream is not to build a better future but to reclaim a lost past, his love for Daisy Buchanan, believing that money can buy what time has taken. The futility of this belief exposes the spiritual bankruptcy of a society where economic success has replaced ethical striving. Gatsby’s mansion, parties, and opulent lifestyle, all symbols of achievement, are revealed as hollow performances masking loneliness and longing.

The material excess of the novel mirrors the indulgent consumerism of the decade. Fitzgerald’s detailed descriptions of Gatsby’s parties (the orchestras, champagne, glittering dresses, and reckless guests) function as social commentary on a culture intoxicated by its own display. The guests, many of whom never meet Gatsby, use his home as a playground for escapism, much like consumers in the 1920s used products to fill emotional voids.8 The spectacle of wealth replaces community, and moral coherence dissolves into amusement. In this context, Gatsby’s pursuit of Daisy becomes an allegory for the American Dream itself: seductive, illusory, and corrupted by the belief that happiness can be purchased.

Tom and Daisy Buchanan represent the moral rot at the top of the social hierarchy. As “old money,” they occupy a realm of inherited privilege and moral carelessness that Gatsby’s nouveau riche world can never penetrate. Their indifference to the damage they cause (Tom’s cruelty, Daisy’s emotional shallowness, their shared retreat into wealth after Myrtle’s death) reveals the moral immunity of the upper class.9 Fitzgerald portrays them as the natural aristocracy of capitalism: powerful, insulated, and unaccountable. The tragedy of Gatsby is that he believes he can cross this divide through wealth alone. His death at the novel’s end exposes the falsity of that hope, suggesting that class mobility in America remains more myth than reality.

The novel’s geography reinforces these social hierarchies and the moral boundaries they conceal. East Egg and West Egg symbolize the divide between inherited and newly acquired wealth; the “valley of ashes,” situated between them, embodies the spiritual and environmental decay produced by unrestrained capitalism.10 The billboard eyes of Dr. T. J. Eckleburg, looming over this wasteland, serve as an unblinking reminder of judgment in a godless world, an emblem of conscience in a society that has replaced divine oversight with market spectacle.11 Through these symbols, Fitzgerald transforms landscape into moral topography, mapping a nation in which moral decay festers beneath the glittering surface of prosperity.

Time itself becomes an instrument of critique. Gatsby’s insistence that one can “repeat the past” epitomizes both personal delusion and cultural nostalgia.12 The postwar generation longed for innocence and stability, but instead found itself adrift in materialism and excess. Gatsby’s desperate attempt to recreate his love for Daisy mirrors America’s attempt to recover an imagined moral purity that no longer exists. Fitzgerald thereby links individual desire to national myth, suggesting that both are built upon denial. In trying to collapse time, Gatsby destroys himself, just as the Jazz Age, with its heedless optimism, was hurtling toward the crash of 1929.

Ultimately, The Great Gatsby transforms personal tragedy into a moral parable about America itself. Gatsby’s failure is not merely romantic but systemic: his dream collapses because it rests on illusions perpetuated by a capitalist culture that prizes wealth over virtue and image over integrity. The final vision of the green light, once a symbol of aspiration, becomes a haunting image of endless yearning. Fitzgerald’s language, elegiac and precise, mourns a national ideal undone by its own success. The American Dream, he suggests, did not die in poverty but drowned in affluence.

Linking the Historical Context and Fitzgerald’s Critique

Fitzgerald’s critique of the American Dream cannot be separated from the consumer culture that defined the 1920s. The novel’s obsession with surfaces (the glitter of parties, the gleam of cars, the shimmer of Daisy’s voice) mirrors the era’s fixation on appearance and possession. Advertising in the 1920s taught Americans that identity could be manufactured through commodities, and Gatsby’s persona is precisely that: a self constructed through style, spectacle, and rumor.13 His carefully curated image (his mansion, his tailored suits, his Rolls-Royce) embodies the seductive logic of consumer capitalism, which promises transcendence through purchase but delivers only emptiness. Fitzgerald transforms the machinery of advertising into metaphor: Gatsby sells himself the same dream America has been selling its citizens.

The novel also reflects the darker underside of the decade’s prosperity; its criminal economies and moral evasions. Prohibition, intended to purify American life, instead created a lucrative black market that blurred the line between enterprise and crime.14 Gatsby’s fortune, earned through bootlegging and speculation, symbolizes how wealth in the 1920s was often inseparable from corruption. This blending of legality and immorality reveals the hypocrisy at the heart of the Dream: success was still revered, even when achieved through deceit. Fitzgerald’s portrayal of Meyer Wolfsheim, the gambler rumored to have fixed the 1919 World Series, anchors this moral confusion in historical reality.15 The Jazz Age, like Gatsby’s world, rewarded audacity and performance rather than integrity.

Class remains the unbreachable wall that gives the novel its tragedy. Despite his immense wealth, Gatsby cannot cross into the sanctified world of the Buchanans. Fitzgerald exposes the illusion of social mobility in the 1920s, a decade that celebrated opportunity while preserving inherited hierarchies. The historian Frederick Lewis Allen observed that even amid apparent prosperity, class divisions deepened as old elites maintained control of culture and capital.16 Gatsby’s yearning to “pass” into Daisy’s world dramatizes this contradiction: in a nation that preached equality, lineage still trumped labor. His death at the hands of George Wilson, a working-class victim of both deception and despair, closes the circle of disillusionment.

In this context, Fitzgerald’s symbols resonate as both personal and historical commentary. The green light, shimmering across the bay, becomes the visual emblem of America’s restless longing, for success, for recognition, for a perfection always just beyond reach.17 The eyes of Dr. T. J. Eckleburg, looming over the valley of ashes, reflect a society that has replaced God with consumption, faith with spectacle. The moral gaze they represent no longer judges; it merely observes. The physical spaces of the novel (East Egg, West Egg, and the gray wasteland between) compose a map of the 1920s United States: a nation divided by class and united by appetite.

By embedding his narrative in the real tensions of his time, Fitzgerald transforms The Great Gatsby into a cultural autopsy of the American Dream. The novel’s critique is not nostalgic but diagnostic, exposing how postwar affluence eroded the ethical foundation of national identity. In portraying a world where dreams are commodified and desire is endless, Fitzgerald anticipates the broader collapse that would follow, the crash of 1929 and the Great Depression.18 His vision endures because it is historical as well as moral: a mirror of an age that mistook glitter for gold, and a warning to every era that follows.

Conclusion

Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby endures because it captures the moral paradox at the heart of the American Dream. The novel’s beauty lies in its disillusionment: it neither condemns ambition outright nor glorifies it, but rather shows how ambition becomes corrupted when detached from ethics. In the postwar prosperity of the 1920s, material wealth became the new measure of virtue, and social status replaced moral standing. Gatsby’s life dramatizes this reversal. His dream is rooted in the quintessentially American faith that reinvention and effort can overcome origin, but his pursuit transforms that ideal into spectacle and deceit. Fitzgerald’s tragedy lies not only in Gatsby’s fall but in the society that made such a fall inevitable.19

Viewed within its historical moment, The Great Gatsby reveals how the dream of equality and opportunity had already collapsed beneath the weight of corporate capitalism. By the mid-1920s, the United States had become a consumer republic, where identity and aspiration were dictated by markets and advertising rather than conscience or community.20 The novel’s world of mansions, motorcars, and moral vacancy reflects this cultural redefinition. Its characters chase pleasure and possession because those are the only currencies left to measure success. Fitzgerald’s critique is therefore both social and spiritual: America’s economic triumph conceals a profound emptiness, a loss of purpose that wealth cannot fill. The green light, once a beacon of hope, becomes the faint glow of a civilization blinded by its own glitter.21

Fitzgerald also offers a warning about history itself. The novel’s final lines, Nick Carraway’s meditation on the past that “beats us back” even as we strive forward, resonate as prophecy.22 The Jazz Age’s heedless optimism ended in the collapse of 1929, but the dream it embodied continues to haunt American consciousness. Each generation reimagines the promise of success, believing it can finally reconcile material achievement with moral worth. Fitzgerald’s insight is that such reconciliation may be impossible as long as the dream’s foundation rests on illusion. The tension between aspiration and corruption, between idealism and greed, defines not just Gatsby’s tragedy but the American story itself.23

Ultimately, The Great Gatsby stands as both product and critique of its time, a glittering elegy for a nation enthralled by its own mythology. Fitzgerald translates the pulse of the 1920s into a timeless reflection on ambition, loss, and moral decay. His novel exposes the dream’s transformation from hope to hustle, from virtue to vanity. Nearly a century later, its relevance endures because the questions it poses remain unresolved: Can a society built on consumption sustain meaning? Can success coexist with conscience? Fitzgerald leaves us, like Gatsby, staring across the dark water toward a light that recedes the closer we approach.24

Appendix

Footnotes

- “America in the 1920s,” Digital History, University of Houston, accessed November 2, 2025.

- “1920s Consumption,” Khan Academy, accessed November 2, 2025.

- Warren I. Susman, Culture as History: The Transformation of American Society in the Twentieth Century (New York: Pantheon, 1984), 273–285.

- “8 Ways ‘The Great Gatsby’ Captured the Roaring Twenties—and Its Dark Side,” History.com, updated April 25, 2024.

- David M. Kennedy, Over Here: The First World War and American Society (New York: Oxford University Press, 1980), 234–240.

- “Advertising in the 1920s,” The Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, accessed November 2, 2025.

- F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1925), 65–68.

- “The Roaring Twenties,” History.com, updated March 6, 2024.

- “The Tragic Consequences of Excessive Wealth in The Great Gatsby,” Ariel Chart, September 2023.

- “The Great Gatsby Themes,” SparkNotes, accessed November 2, 2025.

- “The Great Gatsby: Symbols,” LitCharts, accessed November 2, 2025.

- Garbiñe Maruri Pérez, The Great Gatsby: An Analysis of the American Dream (University of the Basque Country, 2019), 42–46.

- Roland Marchand, Advertising the American Dream: Making Way for Modernity, 1920–1940 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985), 7–10.

- “Prohibition,” National Archives, accessed November 2, 2025.

- “Meyer Wolfsheim and the Real Underworld of The Great Gatsby,” Library of Congress Blog, accessed November 2, 2025.

- Frederick Lewis Allen, Only Yesterday: An Informal History of the 1920s (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1931), 219–223.

- “The Great Gatsby: Symbols,” LitCharts, accessed November 2, 2025.

- Sarah Churchwell, Careless People: Murder, Mayhem, and the Invention of The Great Gatsby (New York: Penguin, 2013), 356–359.

- Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby, 172–180.

- Lizabeth Cohen, A Consumers’ Republic: The Politics of Mass Consumption in Postwar America (New York: Knopf, 2003), 21–24.

- Sarah Churchwell, “Why The Great Gatsby Endures,” BBC Culture, April 10, 2020.

- Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby, 180.

- James Truslow Adams, The Epic of America (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1931), 404–406.

- Alan Brinkley, The Unfinished Nation: A Concise History of the American People, 9th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2015), 723–725.

Bibliography

- Allen, Frederick Lewis. Only Yesterday: An Informal History of the 1920s. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1931.

- Adams, James Truslow. The Epic of America. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1931.

- Brinkley, Alan. The Unfinished Nation: A Concise History of the American People. 9th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2015.

- Churchwell, Sarah. Careless People: Murder, Mayhem, and the Invention of The Great Gatsby. New York: Penguin, 2013.

- ———. “Why The Great Gatsby Endures.” BBC Culture, April 10, 2020.

- Cohen, Lizabeth. A Consumers’ Republic: The Politics of Mass Consumption in Postwar America. New York: Knopf, 2003.

- Fitzgerald, F. Scott. The Great Gatsby. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1925.

- Kennedy, David M. Over Here: The First World War and American Society. New York: Oxford University Press, 1980.

- Marchand, Roland. Advertising the American Dream: Making Way for Modernity, 1920–1940. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985.

- Maruri Pérez, Garbiñe. The Great Gatsby: An Analysis of the American Dream. University of the Basque Country, 2019.

- Susman, Warren I. Culture as History: The Transformation of American Society in the Twentieth Century. New York: Pantheon, 1984.

- “1920s Consumption.” Khan Academy. Accessed November 2, 2025.

- “Advertising in the 1920s.” The Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. Accessed November 2, 2025.

- “America in the 1920s.” Digital History. University of Houston. Accessed November 2, 2025.

- “8 Ways ‘The Great Gatsby’ Captured the Roaring Twenties—and Its Dark Side.” History.com. Updated April 25, 2024.

- “Meyer Wolfsheim and the Real Underworld of The Great Gatsby.” Library of Congress Blog. Accessed November 2, 2025.

- “Prohibition.” National Archives. Accessed November 2, 2025.

- “The Great Gatsby: Symbols.” LitCharts. Accessed November 2, 2025.

- “The Great Gatsby Themes.” SparkNotes. Accessed November 2, 2025.

- “The Roaring Twenties.” History.com. Updated March 6, 2024.

- “The Tragic Consequences of Excessive Wealth in The Great Gatsby.” Ariel Chart. September 2023.

Originally published by Brewminate, 11.04.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.