Codes and Ciphers

Overview

From the beginning of recorded history, codes and ciphers have been used to carry secret messages in times of war and unrest, protecting military and political information should documents fall into the hands of the enemy.

The National Archives holds many secret documents. These span the centuries that mark the development of codes and ciphers – from the simple encrypted messages used in plots against Elizabeth I to the sophisticated system used by the Enigma machine during the Second World War. The race to design ever more complicated codes, and the parallel efforts to break them, continues as computers create ‘unbreakable’ complex encryptions of sensitive data today.

Sometimes codes and ciphers have been broken when the codebook or key was captured or the message contained errors. Sometimes they have been broken through patient examination of mathematical frequencies and an understanding of linguistic patterns. Once a code is broken, all secret communication is revealed – plots are uncovered, plans are thwarted. Codebreakers have sealed the fate of queens and of wars.

16th Century: Mary, Queen of Scots

Cryptography was widely used by political rulers in 16th century Europe. Monarchs, ministers and ambassadors often established cipher offices and employed cipher secretaries to encrypt diplomatic or military information. Mary, Queen of Scots, had a cipher secretary handle her ‘secret’ correspondence in an attempt to communicate with her supporters while she was imprisoned in England. However, the encrypted messages were not as secure as she hoped.

In England the safety of Queen Elizabeth I was constantly under threat from enemies at home and abroad. Anti-Catholic laws created a climate of fear. Mass was banned, those who would not attend Church of England services were fined or imprisoned, lands were confiscated, and to harbour priests was deemed treasonable. Elizabeth’s Secretary of State, Sir Francis Walsingham created a school for espionage in London in the 1570s, recruiting spies from Oxford and Cambridge and developing an unrivalled network of agents and informants throughout Europe. The State Papers are full of letters from informers and accounts of interrogations and searches.

Conspiracies to overthrow Elizabeth were uncovered by Walsingham’s men throughout her reign. From 1571 to 1586 the discovery of a series of plots to establish Mary, Queen of Scots, on the throne led to the trial and execution of Mary and many of her friends and allies.

In 1586 Mary, Queen of Scots, was held prisoner at Chartley under the watchful eye of Sir Amias Paulet, a Protestant loyal to Elizabeth I. In Paulet’s custody Mary’s contact with the outside world was limited to correspondence encrypted by her cipher secretary, Gilbert Curle, and smuggled out in casks of ale. Every letter was intercepted by a Catholic double agent, Gilbert Gifford, who had offered his services to Walsingham in 1585.

‘I have heard of the work you do and I want to serve you. I have no scruples and no fear of danger. Whatever you order me to do I will accomplish.’

(Gilbert Gifford to Sir Francis Walsingham)

Letters between Mary and her allies in England and abroad were painstakingly deciphered and copied by Walsingham’s master forger and cipher secretary, Thomas Phelippes. Letters were then carefully re-sealed and sent on to their intended recipients, who blithely continued with their scheme to establish Mary on the throne.

Different ciphers using unique combinations of symbols, letters, words and nulls were used for different recipients. This document illustrates some of the ciphers used by Mary during her imprisonment at Chartley.

‘There be many means in hand to remove the beast that troubles the world.’

(Thomas Morgan to Gilbert Curle, referring to Elizabeth I)

Encouraged by her supporters abroad (Gifford, Paget, Mendoza, Morgan and Ballard), Anthony Babington wrote a long letter to Mary, Queen of Scots on 6 July 1586. This letter revealed the details of what has become known as the Babington Plot. Babington asked for Mary’s approval and advice to ensure ‘the dispatch of the usurping Competitor’ – the assassination of Elizabeth I.

Mary’s reply on 17 July sealed her fate. It fell into the hands of Thomas Phelippes, who copied the letter, added the gallows sign, and forged a short postscript asking Babington for the names of those involved. This is the postscript and cipher kept by Walsingham and used as evidence against the conspirators and the Queen of Scots.

Within days Babington and his colleagues were arrested and taken to the Tower. Mary’s secretaries were interrogated and her belongings were seized and searched. Seven of the conspirators were dragged to St. Giles’ Fields and brutally executed on 20 September 1586.

Mary was taken to Fotheringay Castle and put on trial in October. Throughout the proceedings she protested her innocence and denied all knowledge of the plot, but the letters were produced as evidence of her guilt. After months of delays Elizabeth signed Mary’s death warrant on 1 February 1587. Seven days later Mary was beheaded in the Great Hall at Fotheringay. Bonfires were lit and bells were rung throughout the country in celebration.

In 1571 a plot was discovered involving Philip II of Spain, Pope Pius V and the Duke of Norfolk, as well as Mary’s advisor, the Bishop of Ross, and Mary herself. At its heart was Roberto Ridolfi, a Florentine banker based in London. Ridolfi traveled to Rome and Madrid to raise support for an invasion of eastern England and an uprising of Catholics, which would be followed by the marriage of the Duke of Norfolk to Mary, Queen of Scots, who would seize the English throne. When Ridolfi’s messenger was arrested at Dover, incriminating letters were seized and Norfolk was arrested, tried for high treason and found guilty. He was executed on Tower Hill on 2 June 1572. Ridolfi was abroad when the plot was uncovered and escaped this fate. Elizabeth was reluctant to authorise the execution of a fellow queen, but Mary was kept under ever-tighter surveillance.

Francis Throckmorton was arrested in November 1583 by Sir Francis Walsingham’s agents. Under torture he revealed a plot to invade England and place Mary on the throne, naming several allies in his confession. Throckmorton was executed and Bernardino de Mendoza, the Spanish ambassador, was sent back to Spain. This conspiracy was one of the reasons the symbolic Bond of Association was devised in 1584 to protect Elizabeth’s life against all threats from enemies within the realm and without. Again, Parliament and Council believed the Queen of Scots should be executed. Again, Elizabeth refused to admit that Mary had been plotting against her.

19th Century: General George Scovell

George Scovell was chief codebreaker for the Duke of Wellington. During the Peninsular War of 1808-1814 he developed a system of military communications and intelligence gathering for the British that intercepted French letters and dispatches to and from the battlefield, and cracked their codes.

The wars that followed the French Revolution and the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte ushered in a new era of intrigue and bloodshed. Most of Europe fell before Napoleon’s Grand Armée. In 1808 Napoleon turned his attention to Portugal and Spain, occupying Lisbon and Madrid and placing his brother Joseph on the Spanish throne. The Portuguese and Spanish resisted and sought British aid. The first British troops set foot on Portuguese soil in the summer of 1808. For the next six years Spanish and Portuguese fought alongside the British army and waged a guerilla war on the occupying French forces.

Under Wellington’s command, codebreaking and intelligence gathering played an important role in British victories such as Oporto (1809), Salamanca (1812) and Vittoria (1813), and Scovell was a key part of these activities.

George Scovell served as an officer in the Intelligence Branch of the Quartermaster-General’s department. A gifted linguist, he was placed in charge of a motley group of Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, Swiss and Irish soldiers and deserters recruited for their local knowledge and language skills, and called the Army Guides. They began to develop a system for intercepting and deciphering encoded French communications.

The French encrypted communications in 1811 using simple ciphers known as petits chiffres. These were designed to be written and deciphered in haste on the battlefield and were generally short notes of instruction or orders, based on 50 numbers. In the spring of 1811 they began to write letters with a more robust code based on a combination of 150 numbers, known as the Army of Portugal Code. George Scovell cracked it within two days.

At the end of 1811 new cipher tables were sent from Paris to all French military leaders. Based on 1400 numbers and derived from a mid-18th century diplomatic code, the tables were sent with cunning guidelines to trick the enemy, such as adding meaningless figures to the end of letters (codebreakers would often try to tackle the end of a letter first, looking for the standard phrases which close formal correspondence).

For the next year Scovell pored over intercepted documents. He made gradual progress using letters that contained uncoded words and phrases, so that the meaning of coded sections could be inferred from the context. The information on troop movements gathered by Scovell’s Army Guides was also crucial when making informed guesses about the identity of a person or place mentioned in coded letters, solving one more piece of the puzzle.

When a letter from Joseph to Napoleon was intercepted in December 1812, Scovell had cracked enough of the code to decipher most of Joseph’s explicit account of French operations and plans. This information allowed Wellington to prepare for the final battle for control in Spain (Vittoria) on 21 June 1813. That night British troops seized Joseph Bonaparte’s coaches and discovered his copy of the Great Paris Cipher table. The code was broken.

In 1811 George Scovell was given a book: ‘Cryptographia, or The Art of Decyphering’ by David Arnold Conradus. It contains a series of rules and principles for creating and breaking codes and ciphers. It also provides sample problems and instructions for dealing with ciphers in English, German, Dutch, Latin, French and Italian.

Scovell experimented with different encryption methods based on the principles in ‘Cryptographia ‘. He devised a method of ensuring that the British had a common cipher to protect their dispatches by sending copies of the same dictionary to each headquarters. By his system, 56C2 would direct the reader to page 56, column C and the second word down. Although simple, this was a strong and successful code.

This is one of the many simple ciphers that George Scovell solved. Once he had passed the deciphered versions of letters to the Duke of Wellington, he was apparently allowed to keep many of the original encrypted letters, which have survived together with his own calculations in his papers held at the Public Record Office.

20th Century: Enigma

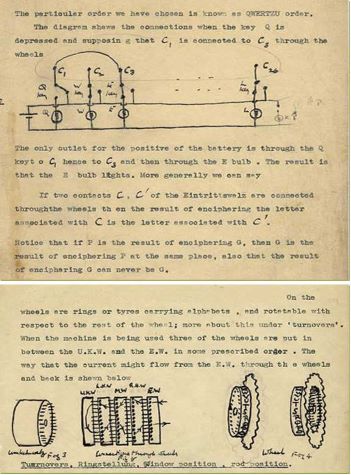

During the Second World War German officials and military forces used an innovative electro-mechanical device known as the Enigma machine to protect their top-secret radio traffic. Though the historical documents (held at the Public Record Office) remained classified until the 1970s, the story of the breaking of the Enigma cipher is now one of the most celebrated of the war.

The Enigma machine was invented by Arthur Scherbius and produced commercially for the banking industry in 1918. The German Navy saw its potential for military use and adapted the system of rotors, keyboard and electrical wires. Resembling a typewriter, the machine was portable and ideally suited to use in combat, and was quickly adopted by all branches of the German armed forces.

Polish cryptanalysts made great strides in understanding the design of the military Enigmas and even constructed several versions of the machine. In 1939 the Germans began strengthening their system by changing the cipher every day. The German Navy equipped their Enigma machines with extra rotors and separate codebooks to create ever more complex encryptions. Enigma protected German radio communications, allowing U-boats to inflict massive losses on commercial and military shipping around Britain and the Luftwaffe to strike suddenly with devastating effect.

Throughout the war a team of British and Polish mathematicians and cryptanalysts were based at Bletchley Park (codenamed Station X), working round the clock to unscramble the streams of intercepted information. Enigma created a new form of encryption based on mathematics, not language. An understanding of letter frequency and linguistic patterns would not crack enigma encoded messages. The capture of an Enigma machine and codebooks from a German U-boat on 9 May 1941 and other more conventional acts of espionage led to significant breakthroughs.

A basic flaw in the design of Enigma was that no letter of the alphabet could ever be represented by itself once enciphered – a could never be a, z could never be z. Together with errors in sent messages and the German habit of using standard phrases at the start of each communication, this allowed cryptanalysts to establish informed ‘guesses’. Nevertheless, without a swift mechanical deciphering system, Enigma’s 150,000,000,000,000,000,000 combinations were practically unbreakable.

Alan Turing (1912-54) was the leading mathematician at Bletchley Park. He’d been recruited from Cambridge University where he had created the pioneering Turing Machine, a forerunner of the modern computer able to perform calculations at astonishing speed.

Turing and Gordon Welchman, a fellow Cambridge mathematician, set to work improving a Polish machine, Bomba, which was built before the war to crack earlier versions of Enigma. The new Turing-Welchman Bombe was perfected in 1940 and they began deciphering Luftwaffe communications. Once set in motion, it would search through all possible Enigma rotor variations until the right combination was found. The complex Enigma methods used in German Naval communications were cracked in 1941, then again in 1943 (after the Navy had introduced extra components to the system).

In January 1943 Tommy Flowers, a Royal Post Office engineer, was sent to Bletchley Park to build an electronic machine to decipher the Lorenz cipher, a complex encryption system used by Hitler and the German High Command.

Over the next nine months, along with a few dozen technicians, he built the first large, high-speed, electronic valve programmable logic calculator. It measured 5 metres long, 3 metres deep and 2.5 metres high, and was assembled from telephone exchange parts.

Colossus could process 5,000 letters per second. It enabled the Allies to eavesdrop on the German High Command before D-Day. The deciphered high-grade signals intelligence was known as ULTRA and it provided critical information on troop positions in Normandy before the Allied invasion began on 6 June 1944.

Spies

Overview

Think of spies and you might picture a suave James Bond-like gentleman working for a rich and mysterious organisation with all the characteristics of a traditional British public school. In fact, it is only very recently that official intelligence organisations were founded and spying was established as a profession. Britain’s permanent secret service was founded in the twentieth century. It was then that spying started to lose its stigma as a dishonest and disreputable way of making a living and started to become seen as a legitimate way of collecting military intelligence.

However, even before spying became a professional business, spies played an important part in British history. There is no better place to find out about these shadowy figures than in the files of the National Archives.

Here are the stories of three spies and the nature of espionage in their time. There is the Elizabethan spy, whose loyalties and responsibilities were sometimes ambiguous; there is the nineteenth century spy, who would have denied being a spy at all; and the Second World War spy, who operated in a complex network of agencies and alliances.

16th Century: Anthony Standen

Antony Standen passed information from Europe to Elizabeth I’s ‘spymaster’ Sir Francis Walsingham. His intelligence reports on the Spanish Armada made him a key figure in the Elizabethan secret service. Yet for almost thirty years Standen was a Roman Catholic refugee from Protestant England. Despite a knighthood from Elizabeth, he was never able to reconcile loyalty to his religion with service for his country.

Walsingham’s duty was to protect the Queen, her sovereignty and her religion, not only from plots inside England, but also from the danger of invasion. Philip II, King of Spain, had once been a suitor of Elizabeth’s but wanted to remove her from the throne and replace her with a Catholic monarch. While England remained isolated in Europe, Spain under Philip grew and prospered. By 1585 the two countries were at war – and Spain’s navy was as big as England’s and the Netherlands’ combined.

Walsingham wanted to find out if and when Spain was going to invade. One of his spies in Europe was Standen, a restless and adventurous Catholic who had left England for Scotland in 1556 with Lord Darnley. In 1565 Standen went to France and in the early 1580s he seems to have settled in Tuscany. In Florence Standen used the pseudonym ‘Pompeo Pellegrini’. He made friends with Giovanni Figliazzi, Tuscan ambassador to Madrid and an excellent source of information about developments in Spain. Although Walsingham was probably in contact with Standen from about 1582, it was not until the spring of 1587 that a regular correspondence began and Standen started to receive £100 a year from the Queen for his service as a spy.

In this letter, partly in code, Standen reports that he has found out from Figliazzi, the Tuscan ambassador, that four Genoese galleys have been sent to Spain. Standen also notes that Walsingham mentioned his ‘desire [of] diligence in intelligence of Spanish matters’ in a previous letter.

Standen realised that he could get even closer than this to Spanish sources and in the final paragraph he writes that he has borrowed 100 crowns to send an unnamed Flemish man to Lisbon. There the Fleming, ‘a proper fellow’ who ‘writeth well’, will make contact with his brother, a secretary to the Marquis of Santa Cruz, the Spanish Grand Admiral, and send back more information about the Armada.

Through Standen, this spy sent vital intelligence to England about the coming Armada for the next two years. For example, he was almost certainly the source of a list of all the ships, men and supplies in the Spanish navy, which came into Walsingham’s hands sometime in 1587. This information proved that the Armada would not, as England had feared, be ready to sail that year.

This is Sir Francis Walsingham’s copy of a letter to Antony Standen, whom he refers to as ‘AB’. He confirms that Sir Francis Drake was able to use Standen’s intelligence to attack the Spanish fleet at Cadiz, seriously damaging Spain’s readiness for invasion. Walsingham says Drake ‘fired thirty of great ships and sunk two galleys’. He also discusses the possibility of a French alliance with Spain and asks Standen to go to Rome to find out more about Italian intentions. Standen was always concerned that Queen Elizabeth should not doubt his loyalty and he must have been relieved to read Walsingham’s comment that she is grateful for his work and hopes he will continue to serve her well.

There are many similar letters in the State Papers, showing how close a spy like Standen allowed Walsingham, hundreds of miles away in England, to get to the secret councils of his enemies in Europe. In 1588 Standen moved to Madrid and he continued to send information, not only about the Armada, but also about illegal trade.

In 1593 Standen finally ended his exile and returned to England. By then Walsingham had died and Standen did not receive much of a welcome. Little is known about his later life, but it seems that in one of his last missions to Italy, under James I, Standen’s desire to reconcile his two loves, England and the Roman Catholic church, got him into trouble with his employers. On his return to England Standen was imprisoned in the Tower of London.

19th Century: Colquhoun Grant

Colquhoun Grant was one of the Duke of Wellington’s most famous intelligence officers, but he never thought of himself as a spy. In the nineteenth century spying was still considered an underhand and dishonest way of warfare. To brand Grant a spy would have been to cast doubt on his status as an officer and a gentleman.

Grant was born in 1780 in Morayshire, the youngest of eight brothers. He became an infantry soldier before he was fifteen and his army life was dominated by the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte in Europe and the threat of cross-Channel invasion. In 1808 he followed Wellington to Spain and Portugal for the Peninsular War.

Wellington soon realised that the French outnumbered his forces. He therefore needed to have as much advance information as possible and he developed a network of intelligence officers and local spies. He valued both strategic information, gathered by the interception of enemy letters, and tactical intelligence, gathered by men in the field such as ‘exploring officers’.

Colquhoun Grant was one of Wellington’s most trusted and experienced exploring officers. He had a reputation as a fearless, intelligent man and a good linguist. On 16 April 1812 Grant and his local guide, Leon, found themselves surrounded by French soldiers near the Spanish-Portuguese border. Grant prided himself on always wearing uniform, even behind enemy lines, because this distinguished him from a spy who would use ‘ungentlemanly’ methods such as disguise and deception. He was conspicuous in his scarlet jacket and was captured. Leon, not in uniform, was shot.

Grant was treated by his French captors as a fellow officer and gentleman and was invited to dine with Napoleon’s trusted commander Marshal Marmont. The Marshal was eager to learn more about the great Wellington, but he became angry when Grant would give nothing away. The next day Marmont gave Grant the chance to sign his parole. Believing that this would allow him more rights than an ordinary prisoner and possibly the chance to continue to send messages to Wellington, Grant agreed.

Marmont and his Chief of Staff, General de la Martinière, remained suspicious of Grant and wanted to get him as far away from the front as possible. They were right to be suspicious, as Grant used the leniency of his French guards to continue to send and receive messages.

While the French held Colquhoun Grant captive, Wellington received word that Marshall Marmont was willing to make an exchange of prisoners. He did not believe the French offer because of this letter, intercepted by Spanish guerrillas. The letter and an attached parole document were written en clair (in plain script rather than code or cipher).

The letter is from General de la Martinière to General Clarke, French Minister of War, saying that Grant is not to be released, but must be accompanied as far as Bayonne. De la Martinière superficially adheres to the ‘gentlemanly’ conduct of war by saying Grant is to be treated as an officer. In fact, everyone would have understood the significance of the final sentence: ‘His Excellency thinks that he should be watched and brought to the notice of the police’. The French considered Grant to be dangerous and, to all intents and purposes, a spy to be dealt with by the police, not the army.

Grant saw a copy of this letter and decided that it made his agreement to parole worthless. He escaped and passed himself off as an American officer, travelling to Paris with a French general. In Paris, still in the guise of an American and now even closer to Napoleon, he sent many messages to Wellington in Spain. He returned to England and eventually rejoined Wellington at the front, continuing to serve as a senior intelligence officer for many years.

20th Century: Nathalie Sergueiew, alias “Treasure”

Sergueiew was one of many agents who double-crossed the German secret service during the Second World War. Between 1943 and 1945 Sergueiew’s contacts in the Abwehr believed her to be a loyal German spy. In reality, she was sending them deliberately misleading messages composed by the British secret service. As ‘Treasure’, Sergueiew did valuable work for MI5 yet her British spymasters began to suspect that she lacked discretion and commitment.

Nathalie Sergueiew was born in Russia in 1912. After studying in Paris she traveled around Europe, improving her mastery of several languages including German, French and English. In the mid-1930s she worked as a journalist in Germany, once interviewing Hermann Goering. At this time she began to admire Nazi ideology and personalities. However, when a journalist friend first approached her to work for the German intelligence service in 1937, she refused. By the time the war had started and she agreed to work for the Abwehr, she had already decided that her real loyalties lay with the Allies and she would do all she could to help them from within the German intelligence system.

Sergueiew met her Abwehr boss, Emil Kliemann, in Berlin and began to learn espionage skills such as secret ink writing, ciphers, radio telegraphy and how to identify different Allied uniforms and equipment. She hinted to her German employers that they should send her to England. At the same time she told the British authorities that she intended to double-cross. In 1943 she arrived in England and was immediately interrogated by MI5, who gave her the alias Treasure.

As soon as German agents were recruited to the British double-cross system they were quizzed about German espionage methods. In her interview Nathalie Sergueiew recounted the story of her life, described the appearance, character and relationships of her Abwehr contacts, and explained the unique cipher she was taught, which was based on the pages of a certain edition of a French novel. In this extract Sergueiew describes the methods of secret ink writing she learnt in Germany.

It was vital to MI5 to make the communications sent by double agents to Germany as convincing as possible. At first Treasure sent messages to Kliemann in secret ink or encoded letters, but later she used a radio transmitter set. She passed to him false information concocted by MI5 as part of an elaborate and successful deception plan to keep D-Day secret. Treasure led Kliemann to believe that there were very few troops in South West England and that she had a boyfriend in the 14th Army (a non-existent unit invented by the Allies). This information fitted in with messages from other double agents and supported the Germans’ false belief that the Allies would land at Calais rather than in Normandy. In this letter the deputy head of the Government Code and Cypher School thanks Sergueiew and her colleagues for helping to break codes and deceive the enemy.

Treasure was an effective double agent, but according to Masterman, the architect of the double-cross system, she was also ‘exceptionally temperamental and troublesome’. In conversations with her MI5 handler, Mary Sherer, Treasure revealed that she had let slip her double identity to an American soldier with whom she had an affair. She also threatened to stop working for MI5 unless they arranged for her beloved pet dog left in Spain to join her.

One month before D-Day, Treasure admitted she had agreed a secret signal with her Abwehr contact, Kliemann, so he would know if her transmissions were genuine. This meant that if another agent took over her transmissions, her cover would be blown, possibly putting at risk the whole network of double agents. In this document, Colonel Robertson, Sherer’s boss, records the angry meeting he had with Treasure in which he told her that her services were no longer required because her behaviour endangered the Allies.

The next day Sherer met with an upset Sergueiew, who suddenly said she would give Sherer the secret code agreed with Kliemann. She quickly wrote it down. This is that original note.

Sergueiew returned to France, but this was not the end of MI5’s troubles. In 1944 Robertson discovered that she intended to publish her memoirs, in which she referred to her MI5 handlers as ‘gangsters’ and refused to hide their identities. Robertson tried to talk Sergueiew into giving up the manuscript, but it was eventually published in 1968, with the title ‘Secret Service Rendered’.

Originally published by The UK National Archives under Crown CopyrightOpen Government Licensing.