The buccaneers were largely English, Dutch, and French united by a hatred of Spain and a desire for plunder.

By Mark Cartwright

Historian

Introduction

The buccaneers were privateers who attacked enemies of their state, namely Spain, in the Caribbean and on the American coast (the Spanish Main) throughout the 17th century. Initially hunters and then seamen and soldiers, the buccaneers successfully attacked Spanish ports like Portobelo, Panama, and Veracruz, but they only very rarely captured treasure ships at sea.

The buccaneers were largely English, Dutch, and French united by a hatred of Spain and a desire for plunder. Buccaneers like Sir Henry Morgan (c. 1635-1688), operated with Letters of Marque or commissions issued by colonial authorities, and so they could attack Spanish ships with impunity and even raid ports in the Spanish Empire from the early 1620s to the late 1690s. As all of the colonial powers in the Americas began to invest more in the defence of their colonies, so the opportunities for buccaneers to gain official employment declined, and they turned instead to out-and-out piracy where any ship or port of whatever nationality was regarded as a target worth pursuing.

Name and Origins

The name ‘buccaneer‘ comes from the French terms boucan and boucanier (“barbecuer”) which were themselves derived from the Arawak Indian word bukan. All of these terms were first applied to those European hunters who, from 1620, had camped illegally in the western part of Hispaniola (modern Haiti) and who smoked their meat using a grill and a smoky fire of animal dung and green twigs. This slow cooking method was used as a way to preserve the meat for future use and for sale to passing ships, along with the cured hides. The sale of meat and hides was the boucaniers’ main source of income.

A notable client was the smugglers who sold contraband, particularly manufactured goods, to colonists throughout the Caribbean and Spanish Main, taking away with them crops like tobacco. The English then used the term ‘buccaneer’ to refer to any pirate operating in that part of the Caribbean, even if the hunters were not necessarily pirates. The term gained much wider attention following the publication in English in 1684 of a popular history, The Buccaneers of America by the Dutchman Alexandre Olivier Exquemelin, himself a one-time buccaneer. French buccaneers called themselves filibusters while the Dutch called themselves zee-roovers (sea rovers).

The New World

Spain had been busy colonising and exploiting the New World throughout the 16th century, but rival European countries were soon eyeing this part of the world with envy. Spain was seen as the common enemy of other European powers for several reasons. It was a Catholic country, and the other great maritime nations were Protestant (with the exception of Portugal which concentrated on South America). Spain had a vast new empire and was shipping back a fortune in every treasure ship that sailed from the Americas back to Europe. Thirdly, Spain was refusing to allow other European traders to operate in the Americas. Crucially, Spain had been at war with both France, the Netherlands, and England for much of the first six decades of the 17th century, and the tremendous costs the Spanish Crown had had to bear were reflected in the neglect of its colonies in the Americas.

The New World

Spain had been busy colonising and exploiting the New World throughout the 16th century, but rival European countries were soon eyeing this part of the world with envy. Spain was seen as the common enemy of other European powers for several reasons. It was a Catholic country, and the other great maritime nations were Protestant (with the exception of Portugal which concentrated on South America). Spain had a vast new empire and was shipping back a fortune in every treasure ship that sailed from the Americas back to Europe. Thirdly, Spain was refusing to allow other European traders to operate in the Americas. Crucially, Spain had been at war with both France, the Netherlands, and England for much of the first six decades of the 17th century, and the tremendous costs the Spanish Crown had had to bear were reflected in the neglect of its colonies in the Americas.

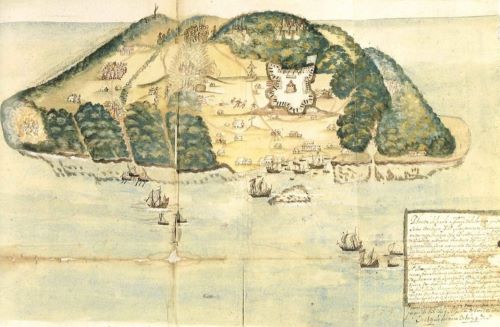

In 1642 the French engineer Jean Le Vasseur built a fortress on Tortuga that bristled with more than 40 cannons. The French officially took over the island in 1665 and, realising the buccaneers were an excellent deterrent to the ever-present threat from Spanish ships, left Tortuga pretty much as it was, concentrating instead on colonising the other side of Hispaniola, Saint Domingue. The French buccaneer François L’Olonais (1630-1668) famously used Tortuga as a base from which to attack Venezuela in 1667. Tortuga was repeatedly attacked by French and Spanish forces in the 1670s and so many privateers moved on to Petit Goâve.

The most notorious of the havens was Port Royal. Jamaica was a British possession from 1655, but the withdrawal of the Royal Navy left it exposed to Spanish warships. Consequently, from 1657, Governor Edward D’Oyley encouraged buccaneers of several nationalities to make the harbour their base and concentrate their plundering activities on Spanish ships. This strategy continued, albeit more covertly, even after 1660 when England and Spain were no longer at war. Subsequent governors were wont to encourage piracy since the presence of many well-armed ships in the harbour significantly lessened the threat from Spain, the Netherlands, and France. In addition, the Caribbean had become a magnet for mariners and soldiers who were no longer required by their countries after the end of the European-wide Thirty Years’ War in 1648. These migrants became an essential tool for the colonial authorities.

Port Royal at its height was awash with people, goods, and riches, so much so that one contemporary author described it as having more cash than London. By 1680, the haven’s prosperity is evidenced by the presence of over 100 taverns. There were, too, so many gaming houses and brothels that a visiting clergyman described Port Royal as “the Sodom of the New World” (Breverton, 260) in reference to the biblical city infamous for its debauchery.

The Scourge of the Spanish Main

Buccaneers were, then, privateers rather than out-and-out pirates since they did not generally attack ships of their home country and many carried official Letters of Marque (aka Letters of Reprisal) or commissions issued by British, French, and Dutch colonial authorities to pursue and attack forces of an enemy state. A colonial governor noted for giving out such commissions was Thomas Modyford, governor of Jamaica. There were, though, many buccaneers who operated without any official backing or with out-of-date or forged Letters of Marque. In any case, the Spanish certainly considered all of them to be no better than pirates and so executed captured buccaneers whether they carried papers or not. It is also true that most buccaneers were out to get what riches they could for themselves, and any assistance to their home country in weakening an enemy state was an entirely secondary consideration.

The buccaneers attacked Spanish ships in the Caribbean and Spanish colonial outposts on the American mainland (the Spanish Main), particularly those situated on what is today the eastern coast of Mexico. In addition, after crossing the isthmus of Panama, they caused havoc on the Pacific coast, too, starting with the raids of Bartholomew Sharp (d. 1688) in 1680 and then Edward Davis from 1684 to 1688.

The early buccaneers often used small, single-masted ships or even canoes to attack their targets. The great strength of the buccaneers was their ability to fire muskets with great accuracy, picking off the enemy onboard larger ships before they could fire their cannons. Buccaneers frequently attacked a ship from astern where there were fewer cannons. Steadily, their success against Spanish shipping swelled their numbers and brought them larger and larger vessels with which to make more attacks. Surprise was a key strategy, and when they became powerful enough to attack land targets, they often attacked Spanish fortifications from the land side rather than the better-defended coastal side. This method was repeatedly used with great effect by the English buccaneer Sir Christopher Mings. Buccaneers were armed with cannons, muskets, swords, daggers, pistols, and grenades.

A peculiarity of the buccaneers, which perhaps contributed to their military success, was the habit of forming partnerships so that a pair of men ate, slept, and fought together. Some members of these pairings even inherited the possessions of their fallen comrade. Certainly, there was a feeling of togetherness amongst the buccaneers as they pursued a common enemy. So, too, booty was scrupulously shared out amongst the men after a raid or capture. All of these factors led to buccaneers being referred to as “Brethren of the Coast”, even if this term is likely a posthumous one given to them by later writers.

To the Spanish, it must have seemed that the whole of Europe was now conspiring against them. Buccaneers could be of all nationalities but were mostly British, French, and Dutch, the principal enemies of Spain (although some disloyal Spaniards were also buccaneers). Besides Europeans, there were, too, a number of former African slaves and indigenous peoples from the Americas. Single groups of buccaneers (the word army may be unsuitable for such an unprofessional and unruly bunch) were often composed of several nationalities, although the French and English generally (but not always) operated independently. The non-Spanish European colonies now had their fighting forces, but what they needed most of all was military leadership. They would find it in such charismatic figures as Henry Morgan.

Sir Henry Morgan

The most infamous of the buccaneers was Captain Henry Morgan. In 1668, buccaneer warfare had developed to such an extent that commanders now led large amphibious “armies”. Morgan led one such multinational force which attacked the Spanish treasure port of Portobelo in Panama. The port was one of the three main Spanish treasure ports and through it went tremendous quantities of silver from Peruvian mines. It was a tempting prize, even if Spain and England had previously agreed not to attack each others’ possessions. Morgan’s commission from the governor of Jamaica was to attack Spanish ships, not ports, but buccaneers rarely bothered with such distinctions, and in any case, loot taken from a ship had to be split with the authorities, loot from raids on ports did not since it was, technically, illegally gained.

Morgan’s base for his series of attacks on Panama was Providence Island, aka Isla de Providencia off the coast of Central America. Providence Island had a good harbour, which was easily defended from its high cliffs. Morgan’s buccaneer force was impressive: 700 men in 12 ships. He began by attacking Puerto Principe on Cuba, but the booty was disappointing. Morgan then turned his attentions to Portobelo which was well-fortified but woefully undermanned and had out-of-date cannons and limited ammunition.

In 1668 Morgan attacked and captured Portobelo. Prisoners, who included women, were tortured to reveal their valuables, a common practice in the world of buccaneers. The town was then ransomed back into Spanish hands, the local population even contributed 100,000 silver pesos to the pot. Morgan rolled on further up the coast, and Panama port was burned to the ground in 1671. The locals did later rebuild their port a little way down the coast, a site which eventually became Panama City. This area of the Spanish Main had long been in decline, and the buccaneers, missing the annual treasure ships, did not get much in return for their efforts. Morgan cheated his men out of what little booty there was, and many were left to nearly starve.

In response to Morgan’s raids, the Spanish demanded action from the British government. Morgan was arrested and sent to London in 1672, but many in positions of power, even if their public voice was different, privately considered Morgan a true patriot whose actions might force Spain to open up their empire to British traders. When the diplomatic dust settled in 1674, Morgan was knighted and sent back to the Caribbean where he was appointed Lieutenant-governor of Port Royal in 1675.

The European buccaneers, wary of the heavily-armed convoys that protected the annual Spanish treasure ships continued to attack the Spanish at their weakest point: the ports. Havana and Cartagena boasted formidable fortifications, but ports like Veracruz, Portobelo, and Panama continued to be attacked as the 17th century entered its final quarter.

The End of the Buccaneers

From the 1670s, Spain finally began to see the value of investing more heavily in the defence of its empire. Morgan’s attack on Portobelo was followed by other large-scale raids like Laurens De Graaf’s attack on Veracruz in 1683. Consequently, the Spanish ensured their fortresses were renovated, soldiers were sent from Spain to man them, and the local militia forces finally received the training and equipment they needed to successfully fight the buccaneers. There was, too, an end of the idea that Spain was the common enemy, as in the latter part of the 17th century, England, France, and the Netherlands began to fight each other for the choicest pieces of the colonial pie. This situation was reflected in the buccaneers who also began to fight each other as the Caribbean became increasingly lawless.

In 1681 the Jamaican authorities finally outlawed piracy, but elsewhere, many buccaneers, particularly the French operating from Saint Domingue, were loath to give up their careers of crime. Many English buccaneers simply moved to new havens such as New Providence in the Bahamas. When the Nine Years’ War (1688-1697) broke out, a significant number of British and French buccaneers found new employment from their respective governments as a valuable addition to their official navies. The last great buccaneer raid was the 1697 French attack and capture of Cartagena. Then the end of the Nine Years’ War and the Peace of Ryswick in 1697 between France, Spain, England, and the Netherlands meant that buccaneers could no longer obtain either official or semi-official employment in the Caribbean and so they decided to use their skills to pursue a life of outright piracy attacking any place or ship they fancied. Thus began the Golden Age of Piracy (1690-1730).

Bibliography

- Breverton, Terry. Breverton’s Nautical Curiosities. Lyons Press, 2010.

- Chartrand, René & Spedaliere, Donato. The Spanish Main 1492–1800. Osprey Publishing, 2006.

- Cordingly, David & Falconer, John. Pirates. Royal Museums Greenwich, 2021.

- Cordingly, David. Under the Black Flag. Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2006.

- Downie, Robert. Way of the Pirate. Ibooks, Inc., 2006.

- Konstam, Angus & McBride, Angus. Buccaneers 1620–1700. Osprey Publishing, 2000.

- Rogozinski, Jan. Pirates! Facts on File, 1995.

- Wood, Peter. The Spanish Main. Time-Life books, 1979.

Originally published by the World History Encyclopedia, 10.19.2021, under a Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.