Examining Roman death rituals including funerals, cremations, and graves.

By Dr. Mario Erasmo

Cultural Historian

Professor and Head Undergraduate Coordinator

University of Georgia

Introduction

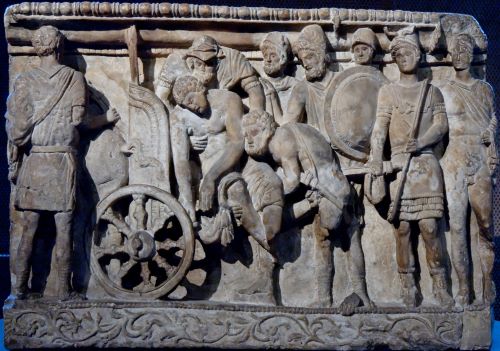

Following the Battle of Cannae, Hannibal cremates the defeated Roman general Paullus, in Silius Italicus’ Punica (10.560–77):

sublimem eduxere pyram mollisque virenti

stramine composuere toros. superaddita dona,

funereum decus: expertis invisus et ensis

et clipeus, terrorque modo atque insigne superbum,

tum laceri fasces captaeque in Marte secures.

Non coniunx native aderant, non iuncta propinquo

sanguine turba virum, aut celsis de more feretris

praecedens prisca exsequias decorabat imago.

Omnibus exuviis nudo iamque Hannibal unus

sat decoris laudator erat. Fulgentia pingui

murice suspirans inicit velamina et auro

intextam chlamydem ac supremo affatur honore:

‘I, decus Ausoniae, quo fas est ire superbas

virtute et factis animas. Tibi gloria leto

iam parta insigni: nostros Fortuna labores

versat adhuc casusque iubet nescire futuros.’

Haec Libys atque repens, crepitantibus undique flammis,

aetherias anima exsultans evasit in auras.1They raised a tall pyre and built soft couches

with green grass. Gifts were piled on top,

funeral offerings: the sword hated by those who felt it

and his shield, once the cause of terror and a proud symbol,

the broken rods and axes captured in battle.

No wife nor sons were there, nor a crowd of men joined

by common blood, nor according to custom, was there

an ancient mask, preceding the tall bier, to honor the funeral.

It was bare of all spoils but Hannibal alone, as eulogizer, was

glory enough. Sighing, he placed on him a covering shining with

rich purple and a cloak woven with gold and spoke a final tribute:

“Go, glory of Ausonia, where it is right for spirits proud in courage

and deeds to go. Glory has already come to you in your

distinguished death: but Fortune directs my labors and

orders me to be ignorant of future events.” So the Libyan spoke

and suddenly, as the flames crackled all around, Paullus’

soul leaping, rose up to the sky.

After a brief description of the bier and funeral offerings of weapons, the narrative emphasizes Paullus’ isolation from his wife, family, and funeral rituals, such as a procession with the imagines of ancestors, as it focuses on Hannibal (Hannibal unus) who is the sole cremator, witness, eulogy deliverer (laudator) and mourner of Paullus’ cremation.2 A cloth shielding Paullus’ corpse from the sun and a woven tunic cover the corpse as Hannibal delivers a brief eulogy. Hannibal addresses Paullus in elevated terms (decus Ausoniae) and speaks with modesty (fas est) as he expresses a commonplace that Fortune determines the fates of humans. His words are for Paullus and they reverse the dialogic direction of epitaphs addressed to passersby who are ordered to leave the gravesite after reading the inscription. The tone of the farewell is dignified and reminiscent of Ennius’ Pyrrhus (Annales, Book 6), who treats the enemy with respect. The pyre is quickly consumed by fire and Paullus’ soul ascends to the sky as the reader realizes that Paullus’ corpse was not described by Silius since the narrative focus was on Hannibal.

Silius’ text alludes to earlier epics, but the narrative makes it clear that Paullus is not receiving a traditional Roman funeral; therefore, it is at once similar and dissimilar to both actual funerals and literary descriptions of funerals familiar to readers. Vergil is the main intertext (cremations of Misenus and Pallas in the Aeneid); but Silius also alludes to pre-Vergilian (Homer; Ennius) and post-Vergilian (Ovid; Lucan; Statius) epic in his handling of the epic funeral trope, in both narrative approach and cremation details.3 By using Vergil’s description of Pallas’ cremation as my starting point, which is itself the mid-point of the epic funeral trope tradition, I explore the connection between death ritual and Latin epic, in particular, death ritual as text and intertext: how Vergil and Ovid use allusions to funerary ritual to pursue various authorial agendas and how they relate to both the literary and ritual experience of the reader. I examine the correspondence between the literary and cultural intertexts in the epic to funerary practices, in particular how varying descriptions of cremations highlight the themes of Aeneas’ relationship with Pallas and his mission to establish a Trojan colony in Italy. I analyzed the Troades of Seneca, which covers similar thematic material from the point of view of funeral ritual as drama and playing dead, but here, I examine cremations as metamorphoses in the Metamorphoses: how Ovid uses cremation as a vehicle for transformation against his Vergilian models and within and between stories to link his Greek and Roman mythological narratives, and to anticipate the apotheosis of Julius Caesar and his own as an immortal poet. Through the associative reading process, the reader becomes a sympathetic participant in a fictive ritual, in the case of Pallas’ cremation, or speechless witness to Hecuba’s tragedy in the Metamorphoses or the apotheoses of both Julius Caesar and Ovid through funerary ritual.4

Cremating Pallas

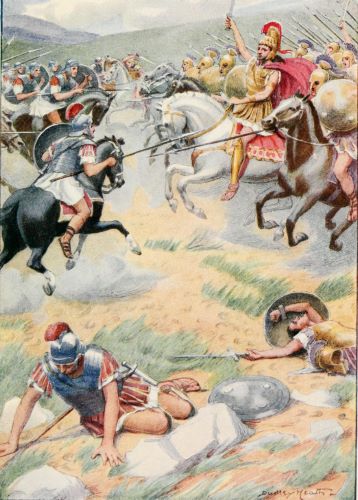

In Vergil, Aeneid 11, Pallas, the young son of Evander, is killed in battle by the Rutulian warrior Turnus and after Evander’s lamentation for his son Pallas’ death, Aeneas directs Pallas’ cremation:

Haec ubi deflevit, tolli miserabile corpus

imperat, et toto lectos ex agmine mittit

mille viros qui supremum comitentur honorem

intersintque patris lacrimis, solacia luctus

exigua ingentis, misero sed debita patri.

haud segnes alii cratis et molle feretrum

arbuteis texunt virgis et vimine querno

exstructosque toros obtentu frondis inumbrant.

hic iuvenem agresti sublimem stramine ponunt:

qualem virgineo demessum pollice florem

seu mollis violae seu languentis hyacinthi,

cui neque fulgor adhuc nec dum sua forma recessit,

non iam mater alit tellus virisque ministrat.

tum geminas vestis auroque ostroque rigentis

extulit Aeneas, quas illi laeta laborum

ipsa suis quondam manibus Sidonia Dido

fecerat et tenui telas discreverat auro.

harum unam iuveni supremum maestus honorem

induit arsurasque comas obnubit amictu,

multaque praeterea Laurentis praemia pugnae

aggerat et longo praedam iubet ordine duci;

addit equos et tela quibus spoliaverat hostem.

vinxerat et post terga manus, quos mitteret umbris

inferias, caeso sparsurus sanguine flammas,

indutosque iubet truncos hostilibus armis

ipsos ferre duces inimicaque nomina figi.

ducitur infelix aevo confectus Acoetes,

pectora nunc foedans pugnis, nunc unguibus ora,

sternitur et toto proiectus corpore terrae;

ducunt et Rutulo perfusos sanguine currus.

post bellator equus positis insignibus Aethon

it lacrimans guttisque umectat grandibus ora.

hastam alii galeamque ferunt, nam cetera Turnus

victor habet. tum maesta phalanx Teucrique sequuntur

Tyrrhenique omnes et versis Arcades armis.

postquam omnis longe comitum praecesserat ordo,

substitit Aeneas gemituque haec addidit alto:

‘nos alias hinc ad lacrimas eadem horrida belli

fata vocant: salve aeternum mihi, maxime Palla,

aeternumque vale.’ nec plura effatus ad altos

tendebat muros gressumque in castra ferebat.After he lamented these things, he orders

the pitiable corpse to be carried and he sends

a thousand men selected from his whole army

to accompany this last honor and to share in

his father’s tears, small solace for a great sorrow,

but owed to a sorrowful father. Others were

quick to weave a soft wicker bier with arbutus

shoots and oak twigs and they shade the raised

couch with a canopy of foliage.

Here they place the youth high on his rustic bed:

just as a flower plucked by the thumbnail of a young girl,

a soft violet or drooping hyacinth, that has

not yet lost its shine or its shape, although

Mother Earth no longer nourishes or gives it strength.

Then Aeneas brought out two cloaks woven with

gold and purple thread, which Sidonian Dido herself

had once made for him, the work a joy to her, and

interweaving the web with fine gold.

Grieving, he put one of these cloaks on the youth

as a final honor, and covered in a fold of it

his hair that would soon burn. Next, he collected

the considerable spoils of the Laurentine battlefield

and ordered them to be brought in a long procession;

he added the horses and weapons that he took as spoils

from the enemy. He even tied the hands behind the backs

of those hostages whom he was sending to the shades of the

dead, about to sprinkle the flames with their sacrificed blood,

and he ordered the army leaders themselves to carry tree trunks

covered with the enemy’s weapons and labeled with their

hateful names. Wretched Acoetes, worn out with age,

was escorted in the procession, now beating his breast

with his fists, now his face with his nails, and collapsed

and his whole body lay stretched out on the ground;

chariots were brought sprinkled with Rutulian blood.

Next, came Aethon, Pallas’ warhorse, without his gear,

crying and he drenched his face with large teardrops.

Others carried Pallas’ spear and helmet, for the other things

Turnus the victor possessed. Then the mourning phalanx

of Trojans followed, and all of the Etruscans and Arcadians

with their arms reversed. After the whole procession of

Pallas’ comrades had advanced some distance, Aeneas

stood and said with a deep groan: “the same grim fates

of war calls me away from here to other tears:

Hail for ever, Great Pallas, for ever farewell.”

He spoke nothing more but turned toward the high walls

of his camp and went inside. (11. 59–99)5

A summary of the cremation preparations, stripped of the description of Pallas’ bier and the epic simile that compares him to a flower, gives the impression that Pallas receives a traditional cremation: he is laid on a bier, Aeneas covers his face with a robe once woven by Dido, as spoils including hostages who will be sacrificed are heaped onto the bier. Aeneas then orders a procession of trophies (tree trunks inscribed with name of the enemy), which is followed by Pallas’ armor, horse and chariot, and a throng of mourners (with weapons reversed) away from the camp. The armor does not include the baldric among other things (cetera, line 91), taken by Turnus; therefore, details of the funeral foreshadow Book 12 where the sight of Pallas’ baldric worn by Turnus prevents Aeneas from sparing him. After the procession departs, Aeneas says farewell to Pallas and returns to camp.

A closer look at the passage, however, with the description of the bier and the epic simile restored reveals a narrative focus that places the cremation of Pallas in a wider literary context: it alludes intratextually to the cremation preparations of Dido and the cremation of Aeneas’ helmsman Misenus and intertextually to the cremation of Patroklos in Book 23 of Homer’s Iliad. As the companion of the epic’s hero, Aeneas, Pallas receives a cremation that at once alludes to earlier literary intertexts and Roman funerary ritual but with departures that situate Pallas’ cremation in a bucolic setting.

In Book 4, Aeneas cuts short his relationship with Dido who commits suicide on a funeral pyre which she had ostensibly constructed to burn Aeneas’ possessions and symbolically mark the end of their relationship. The pyre of piled timber on which Dido places Aeneas’ bed, clothing, and most importantly a wax effigy of the hero is constructed in the courtyard of the palace.6 Dido stabs herself after lighting the pyre and is found too late by her sister, Anna, who tries to staunch the wounds. The reader does not witness the cremation further but like the departing Aeneas, only sees the smoke from a distance.7 Whereas Dido cremates herself with objects that she had given to Aeneas, Pallas is given as funeral honors sacrifices and armor by his fellow Arcadians and Trojan allies and farewell words from Aeneas. Significantly, Pallas is burned in a robe woven by Dido that connects the relationships of these doomed characters to Aeneas. While not an actual description of Dido’s cremation, the passage is important as an intratextual link with the cremation of Pallas in Book 11 which is also connected with the cremation of Misenus in Book 6 and the mass cremations of Trojans and Latins in Book 11.

In Book 6, as the Trojan fleet nears Italy, Misenus jumps overboard under mysterious circumstances and the location of his disappearance is commemorated by being named the Cape of Misenum. Misenus is given a cremation that contains references to Roman practice:

Nec minus interea Misenum in litore Teucri

flebant et cineri ingrato suprema ferebant.

principio pinguem taedis et robore secto

ingentem struxere pyram, cui frondibus atris

intexunt latera et feralis ante cupressos

constituunt, decorantque super fulgentibus armis.

pars calidos latices et aëna undantia flammis

expediunt, corpusque lavant frigentis et unguunt.

fit gemitus. tum membra toro defleta reponunt

purpureasque super vestis, velamina nota,

coniciunt. pars ingenti subiere feretro,

triste ministerium, et subiectam more parentum

aversi tenuere facem. congesta cremantur

turea dona, dapes fuso crateres olivo.

postquam conlapsi cineres et flamma quievit,

reliquias vino et bibulam lavere favillam,

ossaque lecta cado texit Corynaeus aëno.

idem ter socios pura circumtulit unda

spargens rore levi et ramo felicis olivae,

lustravitque viros dixitque novissima verba.

at pius Aeneas ingenti mole sepulcrum

imponit suaque arma viro remumque tubamque

monte sub aërio, qui nunc Misenus ab illo

dicitur aeternumque tenet per saecula nomen.Meanwhile, the Trojans were mourning Misenus

on the shore and paying their last respects to his

ungrateful ashes. First they built a huge pyre loaded

with pine and cut oak and into the sides they wove

dark foliage. In front of it, they set up funereal cypresses

and decorated the top with his gleaming armor.

Some prepared hot water, boiling in bronze pots over the flames,

then washed and anointed his cold body as they groaned in lament.

Next they placed his mourned body on the bier and dressed him in

purple robes, clothing familiar to all. Others undertook the sad duty

of carrying the huge bier, then looking away, applied a torch

under it in the tradition of their ancestors. The offerings, piled high,

burned: incense, ritual meal and bowls filled with olive oil.

After the ashes collapsed and the flames subsided, they

washed his remains, the thirsty ashes, with wine and

Corynaeus placed his collected bones into a bronze casket.

Three times he carried it around his comrades, sprinkling pure water

over them with the branch of a fertile olive tree,

and after he purified the men he spoke his final words.

But dutiful Aeneas placed on the huge mound, his tomb,

the warrior’s armor, his oar, and horn, under that tall

peak, which is now called Mount Misenus after him

and bears his immortal name through the ages. (6.212–35)

The narrative of the cremation is more concise than Pallas’ and we find Roman elements that depict the cremation in conventional terms: a pyre is built with pine and oak (215); surrounded by cypress trees, funereal symbols, (215–17)8; washing of the corpse (218–20)9; dressing of the corpse (220–22); Misenus is placed on a bier (feretrum, 222), as onlookers light the pyre with faces averted from the corpse (223–24)10; cremation with gifts, ritual feast, and containers of olive oil (224–25); quenching of flames and the collection of remains into an urn (ossilegium described at 226–28)11; lustration of the cremation site with the sprinkling of liquids and olive branches12 and the speaking of novissima verba / “final words” (229–30), which according to Varro was ire licet: “it is time to depart.”13 Aeneas then builds a grave mound and piles onto it Misenus’ weapons, oar, and trumpet (232–34). The narrative follows the ceremony from mourning to burial, including the collecting of Misenus’ ashes which goes beyond the ceremony that is described for Pallas. Aeneas will soon see Misenus in the Underworld, which adds an unexpected finality to the funeral rituals since it is due to the funeral which he receives that Misenus is allowed to enter Hades. Vergil connects the cremation with the etymological origins of the name of Cape Misenum.

The narrative of Misenus’ cremation, while seemingly straightforward in its evocation of Roman funeral ritual, is interesting for the narrative emphasis that it receives, in particular, for the description of the cutting of wood for his pyre that introduces the cremation narrative:

itur in antiquam silvam, stabula alta ferarum;

procumbunt piceae, sonat icta securibus ilex

fraxineaeque trabes cuneis et fissile robur

scinditur, advoluunt ingentis montibus ornos.They go into the ancient forest, the deep shelter of wild beasts;

the pine comes down, the ilex struck by the axe resounds,

ash beams and the oak are split with wedges,

and they roll giant ashes from the mountain. (6.179–82)

This passage is part of an epic trope discussed above from Homer for the cremation of Patroklos14 to Ennius for the mass cremation following the Battle of Heraclea.15 Vergil varies the list of trees and active and passive verbs of cutting and falling, but its relationship to the earlier texts is clear. Since Misenus is a relatively minor character in the epic, it is odd that the intertextual allusion to the trope is not used for Pallas instead, who occupies an important narrative role like Patroklos in the Iliad, or even for the mass cremation of Trojan and Latin dead in Book 11, the narrative of which resembles the context of mass cremations in Ennius’ Annales. Aeneid 11.135–38 is preceded by a description of wood gathering for the construction of a pyre, but its formulation is not as tightly alligned with the Homeric and Ennian passages:

fero sonat alta bipenni

fraxinus, evertunt actas ad sidera pinus,

robora nec cuneis et olentem scindere cedrum

nec plaustris cessant vectare gementibus ornos.The tall ash resounds from the two-bladed axe,

pines aiming for the sky are overturned, nor did they

rest from cutting the oak and scented cedar with wedges

nor carrying mountain ash tress on groaning carts.

The absence of the trope in connection with Pallas’ cremation leaves Pallas without an epic intertext for the construction of his pyre, but Vergil fills the intertextual void with a cremation that is grounded in a bucolic rather than an epic landscape. Before turning to the bucolic features and evocations of Pallas’ cremation, however, a closer look at the trope of cremations will illustrate the uniqueness of his cremation.

In Homer’s Iliad, Patroklos, as the companion of Achilles, receives a special funeral that occupies the whole of Book 23. Homer describes the anointing of Patroklos’ body (18.343 ff.); lamentation (18.354–55 and 23.12ff.); the cutting of trees to make a pyre (23.114 ff.); the covering of his corpse with shorn hair (23.135–36 and when Achilles cuts a lock of his own hair); the gift of jars of honey and oil (23.170–71); the sacrifice of horses, dogs, and captured Trojans on the pyre (23.171 ff.); the lighting of the pyre which does not take the first time (23.192); the second successful attempt at night to light the pyre after Achilles prays for favorable winds to fan the flames (23.212 ff.); the cremation (23.217–18); the quenching of flames with wine (23.250 ff.); the collecting of bone fragments and their placement in an urn (23.252 ff.); the construction of a grave mound at the site of the cremation (23.255 ff.); and funeral games (23.262 ff.). In many ways the cremation of Patroklos (and that of Hector at the epic’s end) prefigures the funeral honors that await Achilles since his death occurs outside the narrative of the Iliad. It also interrupts the narrative of the death of Hector, who is killed by Achilles in Book 22 but does not receive his own cremation, described in the barest of terms, until the end of Book 24.16

Perhaps because of the close relationship between Aeneas and Pallas, Vergil raises the expectation that the cremations of Patroklos and Pallas would be similar. Both cremations receive a narrative emphasis that breaks the dramatic action of the war in the second to last books of both epics and the details of the gifts and sacrifices, while differing in particulars, highlight the important social status of the deceased and their relation to their heroic counterparts. But there are important differences that become apparent when other literary intertexts and the mass cremation of Trojans and Latins that occurs later in Book 11 and which includes details closer to the cremation of Misenus in Book 6 are considered. Pallas appears to receive a plausible cremation, but Vergil alters aspects of the Roman custom and departs from his Homeric model in favor of bucolic and lyric intertexts to emphasize the close relationship between Aeneas and Pallas without stating the nature of their relationship overtly. Pallas’ cremation emerges as a metaphor for this key relationship in the poem.

Unlike the pyres of Misenus and Patroklos, Pallas is placed on a bier composed of tender shoots and twigs that resembles a rustic bed (11.64–71). The description of Pallas’ cremation is described in tender terms and takes place amidst a pastoral setting, and here we are aided in our interpretation of the passage by Servius, the ancient commentator on Vergil’s Aeneid. Looking first at Pallas’ bier, the word feretrum is a Greek word, perhaps emphasizing Pallas’ Arcadian ancestry, which Servius contrasts with the Latin capulus.17 The feretrum is soft (molle) and composed of arbutus twigs and Pallas lies on a torus, which can refer to a couch or bed, made of shoots of oak saplings that is described as a rustic bed (agresti . . . stramine). It is significant that the word stramen does not seem to have been used before Vergil to denote a bier and is used only here.18 Absent are trees specifically associated with death ritual, such as cypress trees that were present in the description of Misenus’ cremation (6. 215).

Technical terms to describe the pyre (pyras; rogos; busta) and traditional elements of a Roman cremation are absent, but are used earlier in description of Misenus’ cremation and again later in the description of the mass cremations of Trojan and Latin dead.19 In his description of Pallas’ bier, Vergil emphasizes young shoots as a metaphor, perhaps, of the young Pallas and his untimely death, but they are hardly practical: young shoots or sprigs would not burn as effectively as mature or dried wood, and it would take too many over a long period of time to burn since even with mature wood, cremations took several hours to days.20 The description of the pyre does not mention nor does it preclude the possibility that the young shoots would be supplemented by mature wood, but Vergil gives the impression that the pyre could burn and therefore would emerge discordant with nature: nature would grudgingly acquiesce in the burning of the twigs for the cremation but only with great effort over a long period of time.

The description of Pallas’ still handsome corpse amidst the pastoral setting contributes to an underlying erotic tone.21 Servius, for example, describes the setting of Pallas’ bier as a “room” due to the interweaving of branches that shades his couch.22 The unexpressed purpose may be to protect the corpse from the sun, but the bower-like structure under which Pallas lies contributes to the pastoral setting and is reminiscent of the overhanging trees under which shepherds in Vergil’s Eclogues gather and exchange verse.23 An erotic tone is further encouraged by the simile that compares the dead youth to a flower plucked by a young girl (68–71), a violet or hyacinth, which has lyric antecedents in the poetry of Sappho and Catullus (11.21–24; 62.39–44) where the rejected poet compares his love to a flower in a field which a plough has unwittingly cut (the simile is used intratextually by Vergil of the dying Euryalus at Aeneid 9.433–37).24 Servius links the hyacinth in the simile to Eclogue 3.62–63 where Menalcas claims Apollo loves him and that his gifts, the laurel and hyacinth, are always with him, thus connecting Apollo’s love for him with Apollo’s love for Daphne and Hyacinthus.25 Does Servius, in turn, detect an amorous connection between Aeneas and Pallas? Like Vergil, Servius does not say, although the bucolic and lyric intertexts encourage the connection.

While details of the narrative allude to features of bucolic poetry, an allusion to a specific funeral in Bucolic poetry is difficult due to conventions of the genre in which death does not intrude upon the idyllic landscape of Arcadia. In Idyll 7 of Theocritus, the character Simichidas (meeting Lycidas) is never able to see a tomb just off in the distance, whereas Vergil in Eclogue 9, in imitation of this passage, allows Moeris (meeting Lycidas) to see a tomb in the distance.26 Vergil gives his characters and readers a view of death, but he goes further than his Theocritean model in Eclogue 5 by introducing death and death ritual, more specifically the death of Daphnis, to the genre of bucolic poetry.27 In Eclogue 5, the shepherd Mopsus points out a cave to Menalcas that is bucolic in appearance with wild vines growing within, but which emerges as a metaphorical tomb as the shepherds sing about the death of Daphnis and his apotheosis (aspice, ut antrum / silvestris raris sparsit labrusca racemis, 6–7).28 Allusion to death ritual intrudes upon the narrative as Daphnis himself has left directions for his own funeral: he orders leaves to be sprinkled on the ground, shade to cover fountains, and a tomb containing an epitaph (carmen, 42) that he composed himself:

spargite humum foliis, inducite fontibus umbras,

pastores (mandat fieri sibi talia Daphnis),

et tumulum facite, et tumulo superaddite carmen:

‘Daphnis ego in silvis, hinc usque ad sidera notus,

formosi pecoris custos, formosior ipse.’Sprinkle the ground with leaves, draw shade over the fountains,

shepherds (Daphnis orders such things be done for himself),

and make a mound, and add this epitaph to his tomb:

“I was Daphnis in the woods, famous here and to the stars,

the guardian of beautiful cattle, but I was more beautiful.” (40–44)

The landscape, affected by his death, has exchanged violets and hyacinth for prickly flowers.29 The narrative makes no mention of his cremation but the omission keeps Daphnis timeless: the actual time in the narrative in which he is dead is brief since he “lives again” almost immediately in heaven (56–57) as a golden age returns to world of the shepherds.30

Somewhat overshadowed by the pastoral setting and the allusive referents of Vergil’s narrative of Pallas’ cremation is Pallas’ actual corpse. Like bucolic shepherds who only get a glimpse of tombs from a distance, it is difficult for the reader to distinguish Pallas from the landscape setting. The reader is not a spectator to the cremation as he or she is in the cremation of Misenus in Book 6 and the mass cremations of Trojans and Latins in Book 11.31 Since Aeneas follows the funeral cortege for a short distance before turning back to his camp, he does not witness the cremation either. Rather, before Aeneas loses sight of Pallas, he utters farewell words (11.96–98). The model for this speech is Iliad 23.179–83: Achilles’ farewell to Patroklos which is full of expressions of revenge that Vergil removes, but the wording at the beginning of the speech comes from Aen. 3.493–94: Aeneas’ farewell to Andromache, the widow of Hector, whom he encounters on his voyage to Italy: nos alia ex aliis in fata vocamur. The wording at the speech’s close echoes Catullus’ farewell to his brother in a poem that commemorates his visit to his grave in Asia which he will never see again: 101.10: in perpetuum . . . ave atque vale. Lost in the sentimentality is the fact that Aeneas is not speaking these words close to Pallas’ corpse, but rather utters them as the cortege is some distance away. The words do provide a sort of epitaph that gives Aeneas and the reader closure to the cremation. Aeneas’ impromptu epitaph, however, spoken at a distance from the site of Pallas’ pyre and furthermore not recorded on Pallas’ grave marker, must remain elusive since it is fixed in neither time nor place. We follow Aeneas as the epic hero, and we lose sight of Pallas on his bier since the collection of his ashes and his burial are not explicitly stated.32 The diachronic narrative, therefore, that allows the cremation to take place while Aeneas returns to camp and away from the eyes of the reader, keeps Pallas in his flower-like, ever youthful state in a bucolic setting.

Bucolic echoes of the narrative of Pallas’ cremation are more marked when one compares it intratextually to the mass cremations of Trojans and Latins following the cremation of Pallas which, like the cremation of Misenus, more closely follow literary intertexts and Roman funerary ritual. The narratives of the cremations appear successively after wood is cut for the pyre:

Aurora interea miseris mortalibus almam

extulerat lucem referens opera atque labores:

iam pater Aeneas, iam curvo in litore Tarchon

constituere pyras. huc corpora quisque suorum

more tulere patrum, subiectisque ignibus atris

conditur in tenebras altum caligine caelum.

ter circum accensos cincti fulgentibus armis d

ecurrere rogos, ter maestum funeris ignem

lustravere in equis ululatusque ore dedere.

spargitur et tellus lacrimis, sparguntur et arma,

it caelo clamorque virum clangorque tubarum.

hic alii spolia occisis derepta Latinis

coniciunt igni, galeas ensisque decoros

frenaque ferventisque rotas; pars munera nota,

ipsorum clipeos et non felicia tela.

multa boum circa mactantur corpora Morti,

saetigerosque sues raptasque ex omnibus agris

in flammam iugulant pecudes. tum litore toto

ardentis spectant socios semustaque servant

busta, neque avelli possunt, nox umida donec

invertit caelum stellis ardentibus aptum.

Nec minus et miseri diversa in parte Latini

innumeras struxere pyras, et corpora partim

multa virum terrae infodiunt, avectaque partim

finitimos tollunt in agros urbique remittunt

cetera confusaeque ingentem caedis acervum

nec numero nec honore cremant; tunc undique vasti

certatim crebris conlucent ignibus agri.

tertia lux gelidam caelo dimoverat umbram:

maerentes altum cinerem et confusa ruebant

ossa focis tepidoque onerabant aggere terrae.

iam vero in tectis, praedivitis urbe Latini,

praecipuus fragor et longi pars maxima luctus.

hic matres miseraeque nurus, hic cara sororum

pectora maerentum puerique parentibus orbi

dirum exsecrantur bellum Turnique hymenaeos;

ipsum armis ipsumque iubent decernere ferro,

qui regnum Italiae et primos sibi poscat honores.

ingravat haec saevus Drances solumque vocari

testatur, solum posci in certamina Turnum.

multa simul contra variis sententia dictis

pro Turno, et magnum reginae nomen obrumbrat,

multa virum meritis sustentat fama tropaeis.Meanwhile, Aurora had lifted her nurturing light

for miserable mortals, restoring light for their labor and toil:

Both father Aeneas and Tarchon built pyres along the

curving shore. Here, each carried the corpses in the

tradition of their own ancestors, and once the black torches

were applied to the fires, the sky was buried deep in smoke

and shadows. Three times they ran around the burning pyres

in gleaming armor, three times they purified the mournful fire

of the funeral on horseback with the wail of lamentation on their lips.

The earth was sprinkled by their tears, even their armor,

as the clamor of men and the sound of trumpets went up to heaven.

Here some toss the spoils stripped from dead Latins onto the fire,

helmets, ornamental swords, bridles and wheels still warm;

while others tossed items familiar to the dead as offerings: their own

shields and unlucky spear. All around, many oxen were sacrificed

to the god of Death and bristly boars and herds taken from all of

the fields were slaughtered over the fire. Along the whole shore

they watched their comrades’ cremations and tended to the burning

pyres, nor could they be drawn away until the humid night

returned a sky adorned with burning stars.

On another part of the shore, the grieving Latins also

built countless pyres, some men’s bodies they buried in the earth,

some they picked up and carried to the field’s borders or

returned them to the city. They cremated the others uncounted

and unhonored, a massive heap of entangled bodies; then the

broad fields vied with each other as they glowed from the crowding

flames.

When the third day had removed the cool darkness from

the sky, the mourners collapsed the piled ash and the bones mixed in with

the pyre which they weighed down with a warm mound of earth.

Then within the homes in the city of wealthy Latinus, was the clamor

distinct, the greatest concentration of a common grief.

Here mothers and wretched daughters-in-law, here the

tender affection of grieving sisters and children now

without fathers cursed the fatal war and Turnus’ marriage

and demanded that he alone, with his armor and sword,

should settle the war since he was seeking the kingdom

of Italy and the highest honors for himself.

The cruel Drances aggravated things by claiming

Turnus alone was singled out, that Turnus alone was

being demanded to fight. At the same time, though,

many contrary views and arguments were expressed in

favor of Turnus—the great name of the queen gave him

protection and the great fame he enjoyed, earned from his spoils.

(11.182–224)

Turning first to the description of the Trojan cremation, Vergil signals pathetic fallacy from the start by using the verb extulerat, from effero/ecfero, a verb associated with the carrying out of the dead, to describe the arrival of day and at the end with the appearance of burning stars at night.33 Whereas the time of day was not specified in the cremations of Misenus and Pallas, the mass cremation of Trojans takes place at dawn. This contrasts with the mass cremations, in Ennius’ Annales, following the Battle of Heraclea in which Pyrrhus cremates the Roman dead with his own.34 Ennius places the cremation at night for dramatic effect in imitation of the cremation of Patroklos in the Iliad, whose pyre did not light successfully in the daytime (24.785ff.), but did burn during the second attempt at night. Vergil’s cremation of the Trojans takes place at dawn and ends at nightfall, but the smoke from the flames create an artificial night.35

In contrast to the description of Pallas’ cremation, the passage contains technical language for cremations. Servius remarks that words reflecting the three stages of cremation are given: pyras (185) signifies the stack of wood that comprises the pyre; rogos (189) refers to the pyre once it has begun to burn; and busta (201) the burned-out pyre.36 Further references to funeral rituals echo Misenus’ cremation and include a lustratio—a procession around the pyre (188–90); symbolic purification of the cremation site with the tears of onlookers (191); dedication of spoils; and animal sacrifices to Morta (197) the Roman goddess of death. The narrative emphasis is on the performance of the mass cremation and the observance of Roman custom. Friend cremates friend and caringly tends to the flame throughout the day.

The cremation of Trojans serves as a prelude to the cremation of Latins as descriptions of death ritual carry over and connect the disposal of the dead by the two camps. A separate but shared narrative is fitting since these two peoples will eventually, that is historically, unite and become the forefathers of the future Roman race. The focus of the Latin cremation is on the collection of the remains and the relation of the dead to the living. Although the narrative implies a sequential order of events, it is not clear whether the Latin cremation is actually contemporaneous with the Trojan cremations. After some bodies are removed from the battlefield, the remaining corpses are heaped up indiscriminately together (confusaeque ingentem caedis acervum, 207), and given a mass cremation, significantly without any funeral honors (nec honore cremant, 208).37 We are given no explanation why these men were not claimed for a private burial or cremation earlier or why they must suffer an anonymous funeral. The bones are collected and buried after three days and again the emphasis is on anonymity of the deceased and the confusion of body parts.38 Mourning takes place in homes away from the pyres, in particular the town of King Latinus. The emphasis is on the familial relationships between the mourners and the deceased, but nowhere does the text explicitly state that they mourn for any of the soldiers who received a mass cremation (11.215–19).

The mourners use the occasion of their grief to express their anger against Turnus and implicitly make the connection between the deaths of their loved ones and his political aims to obtain Lavinia in marriage, the daughter of King Latinus, who is now promised to Aeneas, in order to secure an alliance between Rutulians and Latins. The mourners’ call for a duel between Turnus and Aeneas over the hand of Lavinia makes the reader aware for the first time in the narrative of the mass cremations of Latins that Turnus is not present as was Aeneas at the cremations of Misenus, Pallas, and the Trojan dead. The nameless Latin dead have been abandoned for a second time, the first time on the battlefield unclaimed by any of the living, but this time by their leader.39

Thus, Vergil presents his readers with two cremation narrative models based on epic and bucolic intertexts. The cremation of Pallas alludes at once to these earlier intertexts and to Roman funerary ritual. Points of departure, however, highlight the unique funeral given to Pallas in which bucolic and lyric intertexts evoke a pastoral setting. Erotic elements offer variations of Roman funerary practices that distinguish Pallas’ cremation from those of Misenus and the mass cremations of Trojan and Latin dead which more closely follow epic precedents and Roman ritual. Unlike the Iliad which ends with the funeral of Hector and the imminent death of Achilles, the poem does not end with the funeral of Turnus that would provide narrative closure to both character and epic and thus avoid turning the poem into an episode of Aeneas’ epic cycle with a fixed ending. Lack of closure, however, reflects the future of Aeneas’ fictional reality beyond Vergil’s text: Evander’s bucolic Arcadia has vanished with the death of Pallas and Aeneas’ young bride must bury her mother Amata and her former fiancé Turnus as Aeneas begins to integrate his Trojans with Latins. The reader must anticipate the hardships that Aeneas will face, but without the sense of closure that accompanies burial and funeral ritual that put the past into context and provide hope for the future.

Ovid: Cremations as Metamorphoses

Overview

Ovid’s Metamorphoses is filled throughout with references to Roman death ritual from funerals, cremations, graves, to epitaphs. From a death ritual perspective, cremations provide closure, but Ovid, as poet, asserts narrative control through his manipulation of death and death ritual and uses cremations to link stories and to continue the narrative flow, often functioning as vehicles for further metamorphoses. Apollo, for example, after performing Coronis’ cremation rites, rescues their son as she burns on her pyre (2.619–30); thus cremation is a source of life (and further narrative material). The cremation of Hercules (9.229–72), in which he constructs his own pyre, is used as a vehicle for further metamorphosis and his deification: Jupiter rescues the divine part of Hercules as his human part is cremated and remains on earth, in a foreshadowing of Julius Caesar’s cremation and deification in Book 15. A variation on the theme is given in the description of Narcissus’ cremation: just before his pyre is lit, his body has been replaced by a flower (3.508–10), therefore metamorphoses prior to cremation rather than as a consequence of it. In a few stories, however, cremations provide narrative detail and closure. Pyramus and Thisbe are cremated and their remains are placed in the same urn (4.166); Niobe’s sons are placed on a bier and mourned by her daughters before they too are slain (6.288–89); the cremation of Aigina plague victims (7.606–13) is used to show the worst side of humanity as plague survivors ignore decency and death ritual customs; and Chione’s father tries to reach her body several times as she burns on her pyre until he is turned into a hawk (11.332–45).

The greatest number of references to cremations, however, comes in Book 13 following the destruction of Troy. Thematically, the narrative of Troy’s fall divides the Greek myths from the Roman myths and legends, as the burned Troy is resurrected in Italy, and introduces Ovid’s mini-Aeneid followed by the teleological focus of the epic, the metamorphosis of Julius Caesar. I would like to focus on the narrative of Hecuba’s sorrows which Ovid presents as a tragedy within his epic.

Ovid’s Hecuba

The narrative of Hecuba’s sorrows resembles a tragedy in format and theme as the epic reader becomes a tragedy spectator.40 The Trojan women are on shore following the destruction of Troy and waiting to be conveyed to their new masters. Following the death of Astyanax, Hecuba is faced with the further tragedies of the slaughter of Polyxena on Achilles’ tomb and the discovery of Polydorus’ corpse. Her tragedy takes place on the shores of Troy and the shores of Thessaly. Ovid’s linking of the two events in his narrative anticipates Seneca’s linking of the death of Astyanax and the sacrifice of Polyxena in his Troades. Ovid centers his double tragedy around funeral ritual/cremation; however, unlike metamorphoses that result from cremation, it is Hecuba who undergoes a physical transformation at the height of her anger and despair.

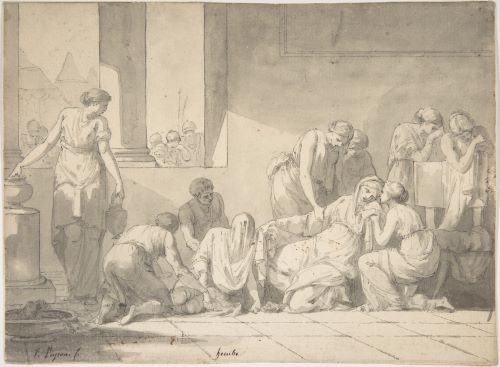

The reader first encounters Hecuba in Troy among the tombs of her children and clinging to Hector’s grave as she is pried away to be taken to Ithaca as Ulysses’ slave:

in mediis Hecabe natorum inventa sepulcris:

prensantem tumulos atque ossibus oscula dantem

Dulichiae traxere manus, tamen unius hausit

inque sinu cineres secum tulit Hectoris haustos;

Hectoris in tumulo canum de vertice crinem,

inferias inopes, crinem lacrimas reliquit. . . .Hecuba was found among the tombs of her sons:

The hands of the Dulichian dragged her away

as she was clinging to their tombs and giving

kisses to their bones, and in her lap she carried

off the gathered ashes of Hector;

on the top of Hector’s tomb she left a lock of her white hair,

poor offering for the dead, a lock and tears. (13.423–29)

The scene arouses pathos as Hecuba kisses the bones of her children as a farewell gesture (of her departure from Troy, unlike their funeral which was her farewell gesture to their deaths). But if they were cremated before burial, the reader wonders how she can kiss their bones (just fingers from the ossilegium and removed from cremation urns implied?). Hecuba carrying off Hector’s ashes and his urn becomes a symbol of her futility to save her children and her future inability to pay her respects at their tombs. The physical disconnect between place of burial and place of funeral ritual has already begun: Hecuba leaves a lock of her hair as a funeral offering to Hector on his tomb, but since she is carrying his ashes, he is no longer buried there. Is Hector’s tomb, which is a symbol for him, also a symbol of the fallen Troy for Hecuba which she will never see again? If so, what should the reader make of her removal of Hector’s ashes from his tomb so that she can bring them to Ithaca as a constant reminder of Troy’s fall and the death of her children? When Hecuba turns into a dog, the text does not say what happens to Hector’s ashes; but if they were re-buried in Thessaly, then Hector would have two tombs, one in Troy and one in Thessaly, which would, presumably, also house the tombs of Polyxena and Polydorus.

The scene quickly shifts to the shore of Thessaly where Hecuba and the Trojan women face the double tragedies of the sacrifice of Polyxena and the discovery of Polydorus’ corpse which is washed on shore at the very moment that Hecuba approaches the sea to fill an urn with water to wash Polyxena’s corpse. The horrors of Troy’s destruction have accompanied Hecuba to another shore, but the narrative of Hecuba’s grief is tragicomic in the unbelievable and consecutive disasters that she meets. Hecuba, therefore, emerges as the thematic link to the double tragedy, as both the recipient and audience of the horrors she experiences, leaving the reader almost breathless as the spectators of her improbably swift suffering.

The narrative of Polyxena’s sacrifice is the main thematic focus of Hecuba’s sorrows. Almost as soon as the ghost of Achilles appears to demand the sacrifice of Polyxena on his grave (13.441–48), she is torn from Hecuba’s arms, in a gesture recalling Hecuba’s embrace of her children’s tombs and sacrificed by Achilles’ son Neoptolemus: . . . fortis et infelix et plus quam femina virgo / ducitur ad tumulum diroque fit hostia busto. / “ . . . brave, doomed and more than a woman, the virgin is led to his grave and becomes a sacrifice over the hated tomb,” 13.451–52. Ovid refers to Achilles’ grave as tumulus and bustum, but the terms are not synonymous, they are sequential: remains of a pyre (bustum) would have been covered by piled earth (tumulus). Polyxena faces death bravely (and in a masculine way); she also gives a final speech to her murderers in which she wishes that Hecuba not learn of her death and asks the Greeks to respect her social status and not to abuse her corpse, but to return it to her mother for burial (13.457–73). Neoptolemus and an audience of onlookers weep as, even in death, Polyxena protects her modesty: tunc quoque cura fuit partes velare tegendas, / cum caderet, castique decus servare pudoris. (even then, while she was falling, she cared to cover her body and to protect the honor of her chaste modesty, 13.479–80). The enjambment of cum caderet imitates the falling of Polyxena’s corpse.

Trojan women collect Polyxena’s body and mourn for her, as the latest victim of Priam’s doomed family, and they reflect on Hecuba’s changed fortunes as the recent queen of Troy and the former mother of many children. Hecuba embraces her daughter’s corpse and pours tears into her daughter’s wounds: . . . huic quoque dat lacrimas: lacrimas in vulnera fundit / “to her she gives even tears: she pours her tears into her wounds,” 13.490. A scene of pathos takes on a grotesque and absurd tone by this detail of tears pouring into Polyxena’s wounds since it focuses the reader’s attention onto and into the holes in her body (the text earlier, however, only specified a single stab wound to the chest at 13.476), rather than the grief of a mother embracing her dead child. Polyxena’s wound is also the focus of Hecuba’s address to her daughter’s corpse that links mother to her daughter’s wound and killer. Hecuba uses language that turns her lament into an impromptu epitaph for her daughter and for Troy, which she starts and then interrupts:

nata, tuae—quid enim superest?—dolor ultime matris,

nata, iaces, videoque tuum, mea vulnera, vulnus:

en, ne perdiderim quemquam sine caede meorum,

tu quoque vulnus habes; at te, quia femina, rebar

a ferro tutam: cecidisti et femina ferro,

totque tuos idem fratres, te perdidit idem,

exitium Troiae nostrique orbator, Achilles;

at postquam cecidit Paridis Phoebique sagittis,

nunc certe, dixi, non est metuendus Achilles:

nunc quoque mi metuendus erat; cinis ipse sepulti

in genus hoc saevit, tumulo quoque sensimus hostem:

Aeacidae fecunda fui! iacet Ilion ingens,

eventuque gravi finita est publica clades,

sed finita tamen; soli mihi Pergama restant.Daughter,—what else do I have?—a final misery for your mother,

daughter, you lie dead and I see your wound, my wound:

so that I would not lose any of my children without slaughter,

you, too, have a wound; but I thought you would be safe from

the sword, being a woman: but you have died by the sword even

as a woman, and that same Achilles, the ruin of Troy and depriver of my

childen,

killed so many of your brothers, has killed even you; but after he fell

from the arrows of Paris and Phoebus, “Now, for certain,” I said, “Achilles

is

no longer to be feared.” Even now, though, I should have feared him;

his ashes in his grave rage against our race, even in his tomb we felt he

was our enemy: I was fertile for the descendants of Aeacus!

Great Troy lies dead, the public disaster was ended by a tragic outcome,

and even though it was ended, for me alone Pergamum still stands.

(13.494–507)

Hecuba self-identifies with the dead Polyxena as mother and fellow victim of Achilles and his son. Her epitaph for Polyxena becomes an impromptu epitaph for herself as she mockingly lists her main life’s accomplishment as having supplied children for Achilles and his son to murder: Aeacidae fecunda fui! By referring to them as descendants of Aeacus, Hecuba frames the loss of her own family within the context of a genealogical animosity. Hecuba also gives an epitaph for Troy: iacet Ilion ingens, and thus she links herself to daughter and fallen city. When Hecuba imagines Penelope pointing her out as her slave, the deictic also imitates the language of epitaphs as though Hecuba sees her fate as Ulysses’ slave synonymous with her death: ‘haec Hectoris illa est / clara parens, haec est’ dicet ‘Priami coniunx’ / “‘here she is, that famous mother of Hector,’ she will say, ‘here is the wife of Priam,’” 13.512–13.

It is only in Hecuba’s lament that she connects the sacrifice of Polyxena with her marriage to Achilles that turns her funeral into her wedding and her burial into her wedding gift:

at, puto, funeribus dotabere, regia virgo,

condeturque tuum monumentis corpus avitis!

non haec est fortuna domus: tibi munera matris

contingent fletus peregrinaeque haustus harenae!but, I think, you will be given a funeral as your dowry, royal virgin,

and your body laid to rest in your ancestors’ tomb!

this is not our house’s fortune: the tears of your mother

will reach you as your gift seeped down by foreign sand! (13.523–26)

The reference to the sand on the shore connects almost immediately with Hecuba’s wish to wash her daughter’s corpse. As she approaches the water’s edge, however, she sees the corpse of her son Polydorus and is struck dumb with grief (13.540–44):

[ . . . ] duroque simillima saxo

torpet et adversa figit modo lumina terra,

interdum torvos sustollit ad aethera vultus,

nunc positi spectat vultum, nunc

vulnera nati, vulnera praecipue, seque armat et instruit ira.[ . . . ] she stood like a hard rock

and held her eyes fixed to the ground,

meanwhile, she raised her grim face to the sky,

now looking at the face of the corpse, now the

wounds of her son, especially his wounds, she

steeled herself and her anger mounted.

Again, wounds are the focus of her and the reader’s gaze. Hecuba is compared to a rock in her grief and recalls Niobe who was turned to stone following the deaths of her children.41 Just as Niobe becomes a tombstone to her children and husband, so too, does Hecuba resemble a tombstone as she marks the place of her son’s death. Grief over Polydorus’ death turns into revenge as she plots the death of his murderer, Polymestor. Her revenge is a digression that interrupts her funeral of Polyxena and which postpones her funeral of Polydorus since she is turned into a dog before either can be completed (13.567–71). Therefore, we witness her grief as metamorphosis as Hecuba changes from mother to childless widow to stone to a dog.

Ovid uses the grief of Hecuba over the loss of her children to connect the story of Aurora’s grieving for her son Memnon (13.576–622). Two mothers, connected to Troy by marriage, are further connected by loss and ritual mourning and yet they mourn differently: whereas Hecuba and the reader gazed on the corpses of Polyxena and Polydorus, Aurora is not able to look at her son’s corpse lying on the pyre (at non inpositos supremis ignibus artus / sustinuit spectare parens, sed crine soluto / . . . / “but his mother was not able to look at his limbs placed on the pyre, but with loosened hair . . . ,” 13.583). Like Thetis, who mourned the death of Patroklos and the impending death of Achilles by wearing a black veil (Iliad 24), thus bridging or, alternately, even separating further, the world of immortals and immortals, Aurora, in ritual mourning for Memnon, loosens her hair which she keeps unbound as she asks Jupiter to honor her son (13.584 ff.). Jupiter grants her request and gives a portent once Memnon’s body begins to burn on the pyre: the smoke that rises takes on the appearance of birds which fight each other until their ashen bodies collapse back onto the pyre as a funeral offering to Memnon (inferiaeque cadunt cineri cognata sepulto / corpora seque viro forti meminere creatas / “their bodies related to the buried ashes fell as a funeral offering and they remembered that they themselves sprang from that brave man,” 13.615–16). The birds reappear each year to mark the death of their parent Memnon. Therefore, cremation as metamorphosis keeps Ovid’s narrative flowing.

Aurora’s connection to the house of Priam, through Tithonus, provides a genealogical link to the fall of Troy and Aeneas’ arrival in Italy. Aurora’s mourning for Memnon further connects the numerous references to cremation that connect the fall of the Troy with the rise of Rome and, ultimately, the comet symbolizing Julius Caesar’s deification. Ovid emphasizes the theme of regeneration through cremation and allusions to rebirth after civil war. On his way to Italy, Aeneas visits Anius, priest of Apollo, on the island of Delos. Anius gives Aeneas a cup on which is depicted Thebes and various funeral scenes that followed the civil war between Polynices and Eteocles, including the death and disposal of Orion’s daughters (13.685–99):

urbs erat, et septem posses ostendere portas:

hae pro nomine erant, et quae foret illa, docebant;

ante urbem exequiae tumulique ignesque rogique

effusaeque comas et apertae pectora matres

significant luctum; nymphae quoque flere videntur

siccatosque queri fontes: sine frondibus arbor

nuda riget, rodunt arentia saxa capellae.

ecce non femineum iugulo dare vulnus aperto,

illac demisso per fortia pectora telo

pro populo cecidisse suo pulchrisque per urbem

funeribus ferri celebrique in parte cremari.

tum de virginea geminos exire favilla,

ne genus intereat, iuvenes, quos fama Coronas

nominat, et cineri materno ducere pompam.There was a city, and you could see seven gates:

this is where the city’s name came from, and told which one it was;

in front of the city were funerals, graves, fires, pyres, and

mothers with disheveled hair and breasts bared for beating

that signified grief; nymphs seemed to cry and lament their

dried-up pools; a tree stood naked without leaves, goats

chewed on the parched rocks. See Orion’s daughters, revealing

masculine wounds to their bared throats and a sword sent through

their brave chests, who died for the sake of their own people,

carried in beautiful processions throughout the city

and cremated before a large crowd.

Then so that their line would not perish, from

the virgin ashes arise two young men whom fame

calls the Coronae, who lead the procession for their

maternal ashes.

The cup focuses on the aftermath of civil war and contrasts its effect on urban and rural life: goats out to pasture are unaffected by human drama. The number of tombs and pyres are not specified, but the narrative focus is on the daughters of Orion who give birth through cremation to two men named the Coronae who immediately assist in the cremation rites of their mothers. While there are echoes of fallen Troy, also important is the theme of regeneration through metamorphosis that foreshadows the rebirth of Rome following the apotheosis of Caesar and the principate of Augustus. The participation of Nymphs in the funeral rituals foreshadows Venus’ mourning for Caesar. Aeneas exchanges gifts for the cup; Ovid gives no indications, however, that he interprets the cup’s images in relation to his own experiences or anticipated future.

The wanderings of Aeneas continue in Book 13 and extend into Book 14 as he approaches Latium. At Caieta, named after Aeneas’ nurse, Aeneas encounters Achaemenides who recounts Ulysses’ adventure with the Cyclops and Macareus who describes the evils of Circe. After these extended stories, the narrative suddenly shifts to the funeral urn of Caieta. Her death and cremation presumably occurred after Aeneas’ arrival, but at no time during the speeches of Achaemenides and Macareus were they described. Caieta is given an epitaph on her tomb (14.441–44):

[ . . . ] urnaque Aeneia nutrix

condita marmorea tumulo breve carmen habebat

HIC ME CAIETAM NOTAE PIETATIS ALUMNUS

EREPTAM ARGOLICO QUO DEBUIT IGNE CREMAVIT[ . . . ] and Aeneas’ nurse, placed in a

marble urn, had this brief epitaph on her tomb:

HERE HE WHOM I NURSED, FAMOUS FOR HIS PIETY, PROPERLY CREMATED

ME, CAIETA, WHO WAS SNATCHED FROM GREEK FIRE.

The epitaph emphasizes the moral virtues of Aeneas (famous for piety before her death for which his pious execution of her funeral rituals is yet another example and also noted), rather than the virtues of the deceased. Aeneas receives mention in the nominative case as Caieta refers to herself in the accusative case, thus showing deference to her ward even in death. The irony of her survival from Greek fire only to be consumed by the fire of her cremation is emphasized through the side-by-side placement of igne and cremavit. Following the quotation of the epitaph, no further mention is made of Caieta and the Trojans leave and quickly arrive in Latium, where Aeneas is given Latinus’ daughter Lavinia in marriage and must fight the rejected Turnus.42 In Vergil’s Aeneid, Anchises dies under mysterious circumstances and his remains are later buried in Sicily.43 Ovid makes no reference to Anchises’ death, and Caieta’s death and burial seem to serve as a substitution. Aeneas arrives in Latium without his father and Nurse in the Metamorphoses and thus emerges as a hero outside of their protective shadows.

Caieta’s cremation is followed by the cremation of Iphis, who hanged him- self after being rejected by Anaxarete. Iphis’ mother embraces the body of her son in a gesture reminiscent of Hecuba’s embrace of Polyxena’s corpse. The emphasis on the dual roles of deceased father and mother which Iphis’ mother must play at his funeral draws attention to her solitude (14.743–47):

accipit illa sinu conplexaque frigida nati

membra sui postquam miserorum verba parentum

edidit et matrum miserarum facta peregit,

funera ducebat mediam lacrimosa per urbem

luridaque arsuro portabat membra feretro.She took her son into her arms and embraced his

cold limbs and, after she spoke the words which wretched fathers say

and carried out the deeds which wretched mothers do,

tearful, she led the funeral throughout the city

and carried his pale limbs on a bier that would soon burn.

Iphis’ bier is carried past Anaxarete’s house and when she sees him lying dead, she turns to stone. The same sentence that informs the reader that the statue of the transformed Anaxarete is displayed on the island of Salamis also makes reference to a temple in honor of Venus: neve ea ficta putes, dominae sub imagine signum / servat adhuc Salamis, Veneris quoque nomine templum / Prospicientis habet. / “so that you do not think that this story is fiction, even now Salamis preserves a statue in the form of the mistress, and has a temple by the name of Venus Gazing,” 14. 759–61. The emphatic, and somewhat forced, connection between the statue of Anaxarete and the temple of Venus links the goddess to a story of unrequited love, but the association also connects the goddess to Iphis’ mother as the narrative anticipates, again, Venus’ own grief over the death of Caesar. The cremation of Iphis is the last one described in the Metamorphoses; yet it, with others, provides an intratextual link with mourning over Caesar’s death and the comet that signals his apotheosis.44

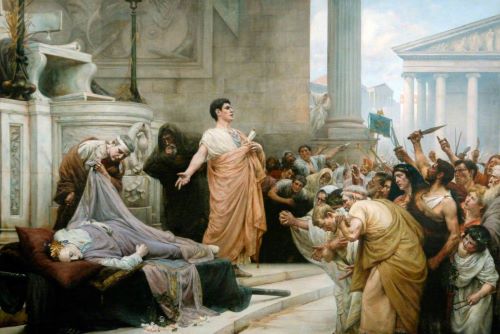

Julius Caesar’s Apotheosis as Cremation

The apotheosis of Julius Caesar is the teleological focus of the poem, but it is not the final metamorphosis which Ovid reserves for himself. Ovid focuses on the assassination of Caesar and the roles played by Venus and Augustus in securing his apotheosis, but not his funeral and cremation. Considering the preceding number and detailed descriptions of cremations that led to further metamorphoses, a reader might expect a description of Caesar’s cremation on the model of Hercules’ cremation in Book 9 (229–72) since it, too, served as a vehicle for his apotheosis. Ovid also deemphasizes the apotheosis of Romulus, the only historical Roman deified before Julius Caesar, and makes no connection between Romulus’ apotheosis and Caesar’s.45 Caesar had assimilated himself with Romulus, but an association with Romulus was also cultivated by Augustus and this may explain Ovid’s reluctance to make explicit any connection between Romulus and Caesar, despite elements for reading Caesar’s funeral as apotheosis through funerary ritual.46 Ovid also downplays historical details of Caesar’s funeral with the result that the comet that signals Caesar’s apotheosis in the Metamorphoses serves as both an apotheosis symbol and a substitution for a description of his actual cremation in order to signal Augustus’ own metamorphosis into the son of a god. Ovid also uses the narrative of Caesar’s apotheosis to emphasize his own role in immortalizing both Caesar and Augustus in the poem.

The narrative of Caesar’s apotheosis is preceded by the introduction of Aesculapius’ cult to Rome (15.622–44). Ovid contrasts Aesculapius’ arrival at Rome, as a foreign god in snake form, with Caesar’s divinity in the city of Rome (15.745–51):

Caesar in urbe sua deus est; quem Marte togaque

praecipium non bella magis finita triumphis

resque domi gestae properataque gloria rerum

in sidus vertere novum stellamque comantem,

quam sua progenies; neque enim de Caesaris actis

ullam maius opus, quam quod pater exstitit huius [ . . . ]He, however, arrived at our shrines as a foreigner.

Caesar is a god in his own city; he, conspicuous in war and peace,

was changed into a new heavenly body, a flaming star, not so

much for wars that ended in triumphs or the accomplishment of civic

deeds or his hastened glory as much as his own offspring; for

there is no greater achievement from Caesar’s deeds, than that

he became the father of him [ . . . ]

The deification of Caesar is stated explicitly before his apotheosis is described in the narrative, as is the role played by Augustus in furthering the deification along. Caesar’s metamorphosis into a star and comet (in sidus vertere novum stellamque comantem) is listed among other res gestae and furthermore it ensured that Augustus would be born the son of a god: ne foret hic igitur mortali semine cretus, / ille deus faciendus erat [ . . . ] / “so that he would not be created, therefore, from mortal seed, Caesar needed to be made into a god [ . . . ],” 15. 760–61.

Caesar’s assassination is then seen from a god’s eye view on Olympus: Venus asks other gods to intervene; however, they cannot contradict rules of fate that separate mortals from immortals. Portents of light and darkness foreshadow the murder of Caesar which serves to contrast with the eventual fire of his comet (15.785–90):

[ . . . ]; solis quoque tristis imago

lurida sollicitis praebebat lumina terris;

saepe faces visae mediis ardere sub astris,

saepe inter nimbos guttae cecidere cruentae;

caerulus et vultum ferrugine Lucifer atra

sparsus erat, sparsi lunares sanguine currus.[ . . . ] also the sad face of the sun

shone a pale light over lands filled with apprehension;

often torches seemed to burn under the stars,

often drops of blood to fall from the clouds;

and the Morning Star was bluish and his face

covered with a metallic darkness, and the Moon’s

chariot seemed stained with blood.

Among other signs of heavenly despair are funereal imagery: the sun’s face is compared to an ancestor mask (imago), and the facial discoloring of Lucifer, the morning star, evokes a diseased and deathlike appearance; therefore gods associated with light go into mourning before the actual murder. The assassination occurs in the narrative gap between the mention of weapons used to kill Caesar and Venus’ mourning (15.799–806):

non tamen insidias venturaque vincere fata

praemonitus potuere deum, strictique feruntur

in templum gladii: neque enim locus ullus in urbe

ad facinus diramque placet nisi curia caedem.

tum vero Cytherea manu percussit utraque

pectus et Aeneaden molitur condere nube,

qua prius infesto Paris est eruptus Atridae,

et Diomedeos Aeneas fugerat enses.Nonetheless, the warnings of the gods were

unable to overcome plots and the coming fates.

Drawn swords are carried into the sacred curia:

for no other place in the city than the curia would

suit the crime and ill-omened murder.

Then truly did Cytherea strike her breast with

both hands and tried to hide her Aenean offspring in a

cloud—the one in which she had rescued Paris from the

dangerous son of Atreus and in which Aeneas

had eluded Diomedes’ sword.

Ovid initially designates the place of murder as templum (801) and then as curia (802), to emphasize Caesar’s divine status and the religious sacrilege of his assassination (pontifex maximus). The sequence and shift in designation from temple to curia also highlights the criminality of the act from a human and civic perspective. Venus beats her breasts in mourning, in a gesture reminiscent of Aurora’s mourning for Memnon in Book 13, but Jupiter predicts Caesar’s imminent deification through her agency and the agency of Caesar’s (adopted) son Augustus (15.818–819).47 Jupiter then prophesies Augustus’ struggles against Caesar’s murderers and Antony and Cleopatra as well as his civic reforms, and instructs Venus to assist in Caesar’ apotheosis:

‘hanc animam interea caeso de corpore raptam

fac iubar, ut semper Captolia nostra forumque

divus ab excelsa prospectet Iulius aede!’“Meanwhile, make his soul, snatched from his murdered

body, into a star, so that as the divine Julius he will always

gaze over our Capitol and forum from his lofty temple!” (15. 840–42)

Venus immediately releases Caesar’s comet unseen in the senate house (but Ovid knows of her role; therefore, he narrates from a privileged position). From a narrative perspective, the speed with which Caesar’s apotheosis occurs is almost as quick as the narrative of his murder. Venus’ unseen participation allows Ovid (and other contemporaries) to postulate divine intervention in Caesar’s apotheosis, although, according to Suetonius, divine honors were voted for Caesar by senators (Divus Iulius, 84.2).48

Ovid is more concerned with the apotheosis of Caesar than with the historical details of his funeral and the disposal of his remains.49 In fact, Ovid’s narrative glosses over and modifies actual events of Caesar’s apotheosis and funeral, but according to the ancient sources, details surrounding Caesar’s funeral were unusual. Ovid’s narrative does not compete with the theatricality of Caesar’s funeral, but rather, it poeticizes Caesar’s metamorphosis and apotheosis by means of Venus’ release of the comet. The narrative of Caesar’s altered form and divine status, however, does reflect a change that had already taken place in Caesar’s portraits. Following the appearance of the comet that signaled Caesar’s apotheosis, a star was added to the heads of his portraits:

Periit sexto et quinquagensimo aetatis anno atque in deorum numerum relatus est, non ore modo decernentium sed et persuasione volgi. Siquidem ludis, quos primos consecrato ei heres Augustus edebat, stella crinita per septem continuos dies fulsit exoriens circa undecimam horam, creditumque est animam esse Caesaris in caelum recepti; et hac de causa simulacro eius in vertice additur stella.50

He died in his fifty-sixth year and was registered among the number of gods, not only by formal decree but by popular conviction. At the games which his heir Augustus first gave in honor of his apotheosis, a comet shone for seven straight days, rising around the eleventh hour, and was believed to be the soul of Caesar received into heaven; for this reason a star is added on top of the head of his statue. (Suetonius, Divus Iulius, 88)

Suetonius links the changes in portraits in the same paragraph as Caesar’s death notice and the appearance of the comet that was linked to his apotheosis. To Romans unfamiliar with the symbolism of the star on Caesar’s portraits, Ovid’s text would serve an aitiological function. Suetonius’ passage lends itself to an iconic or visual reading: the narrative placement of Augustus’ name between Caesar’s death, and his apotheosis reflects the central role played by Augustus in exploiting the comet as a symbol of Caesar’s deification.

If Caesar became a god, then Augustus became the son of a god (Ovid, Met. 15. 745–51, quoted above, actually reverses the priority of Caesar’s apotheosis: he became a god in order for Augustus to become the son of a god). Just as Caesar’s portraits reflected his divine status, Augustus’ portraits also underwent a similar metamorphosis. Statues, such as the portrait of Augustus Primaporta, exploit the emperor’s divine links to Venus, through Caesar, to suggest that Augustus, as the son of a god, is himself a living god on earth. Portraits that depict the emperor as perennially young further suggest the ongoing process of apotheosis during his lifetime.51

Ovid uses the narrative of Julius Caesar’s assassination and apotheosis to link the final lines of the poem to a final metamorphosis: the future apotheosis of himself through his poetry (15.871–79):

Iamque opus exegi, quod nec Iovis ira

nec ignis nec poterit ferrum nec edax abolere vetustas.

cum volet, illa dies, quae nil nisi corporis huius

ius habet, incerti spatium mihi finiat aevi:

parte tamen meliore mei super alta perennis

astra ferar, nomenque erit indelebile nostrum,

quaque patet domitis Romana potentia terris,

ore legar populi, perque omnia saecula fama,

siquid habent veri vatum praesagia, vivam.I completed a work, which neither the anger of Jove

nor fire, nor sword, nor devouring time will be able to destroy.

When it will, let that day, which has control only of this body,

end the span of my uncertain years: nevertheless, in the

better part of myself, I will be carried, immortal, above the lofty stars,

and my name will be everlasting. Wherever Roman power

covers the conquered world, I will be spoken on the lips of men,

throughout all the centuries, if the predictions of poets are true,

and in fame live on.

The framing of poetic achievement in architectural terms evokes Horace’s declaration of immortality at Ode 3.30 (exegi monumentum), but other intertexts that emphasize the flight of the poet to survey the extent of his fame include Theognis, Ennius, Vergil, and Horace (Ode 2.20).52 The listing of the wrath of Jove as a possible factor in diminishing the immortality of Ovid’s poem, however, is unique. The reference to Jupiter’s anger follows Jupiter’s prophecy to Venus that includes Augustus’ future political achievements, among which is the deification of Julius Caesar. Multiple meanings to the reference to Jupiter are possible, including a thematic one: Ovid connects the narrative of Julius Caesar’s apotheosis, through the reference to Jupiter, to his own metamorphosis into an immortal poet. Through fire imagery, Ovid transfers the image of the potential burning of his poem to the future cremation of his own body. Flames, however, will destroy neither poem nor poet. Thus, Ovid anticipates and actualizes, through his verse, his own cremation and apotheosis which will take him beyond the imperium of Caesars and the limits of the stars.

Ovid’s sphragis expresses his own poetic success through a celestial boundary without end (supra astra) that extends beyond the terrestrial imperium destined for Augustus (across the earth and extra sidera) outlined in Vergil’s Aeneid (6.791–97):

hic vir, hic est, tibi quem promitti saepius audis,

Augustus Caesar, divi genus, aurea condet

saecula qui rursus Latio regnata per arva

Saturno quondam, super et Garamantas et Indos

proferet imperium; iacet extra sidera tellus,

extra anni solisque vias, ubi caelifer Atlas

axem umero torquet stellis ardentibus aptum.53Here is the man, here he is, whom you often hear is promised to you,

Augustus Caesar, son of a god, who will found a golden age again

over the fields of Latium once ruled by Saturn and extend the

empire beyond the Garamantes and Indians; beyond the stars

lies a land, beyond the annual path of the sun, where Atlas the

skybearer, on his shoulder, turns the axis adorned with burning stars.

Here, Anchises points out the future Augustus to Aeneas, both of whom will conquer geography and time to achieve immortality. Anchises uses the language of epitaphs to describe Augustus and the limits of his imperium (hic vir, hic est . . . iacet) and the allusion to funeral ritual plays on the conceit that future Roman heroes who are not yet born are already in Elysium in the Underworld, but the epitaph commemorates only Augustus and his achievements. From a narrative perspective, Vergil’s allusion to funeral ritual in introducing the future princeps to his readers and in describing the boundaries of Augustus’ imperium provides closure and nonclosure: descriptions of death or a funeral give authorial control to a poet and Vergil, as epitaph writer, limits Augustus’ fame by marking the passing of its existence before its boundaries are actually demarcated.

From a semiotic perspective, however, Vergil’s epitaph does not mark the physical location of Augustus, who is not in Elysium (at time of composition), despite Anchises’ pointing gesture, and since the future deification of Augustus is anticipated in the text, Augustus will be (however temporary until his reincarnation/birth into the real world) in Elysium and not Tartarus, implying that a favorable judgment has already been passed on him. Vergil’s epitaph, which should mark death, actually allows Augustus to cheat death and make his imperium his final resting place and achievement for fame. The reading process actualizes what is a temporal conceit in the poem (the future fame of Augustus) since it is Vergil’s text that immortalizes both emperor and poet.

Ovid evokes the Vergilian formulation of using death ritual to anticipate the future fame of Augustus which he connects with the deification of Julius Caesar, but it is also tied to and surpassed by his own fame as a poet. The architects of metamorphosis and immortality are themselves transformed and immortalized. Ovid’s sphragis becomes a figurative epitaph that represents a teleology of the poet’s life and literary work that both marks and does not mark a limitless and timeless final resting place for his poetry.

In his exile, however, Ovid wrote an epitaph in the Tristia (3.3.73–76) for himself that wittingly plays on the epitaphic tradition as it refocuses the claim of immortality through his poetry to a declaration of his mortality through his poetry:

HIC EGO QUI IACEO TENERORUM LUSOR AMORUM

INGENIO PERII NASO POETA MEO

AT TIBI QUI TRANSIS NE SIT GRAVE QUISQUIS AMASTI

DICERE NASONIS MOLLITER OSSA CUBENT54HERE I LIE, HE WHO WAS THE PLAYER OF TENDER LOVES

BY MY TALENT, I, THE POET NASO DIED

BUT YOU, WHOEVER YOU ARE WHO HAVE LOVED, AS YOU WALK

BY, PLEASE

SAY, “MAY THE BONES OF NASO LIE LIGHTLY.”

The epitaph qualifies and undercuts the sphragis and its placement in the Tristia literally marks Ovid’s life and career as a poet even though he considers the poems themselves as a greater monument (monimenta 3.3.78) than his epitaph.55 Ovid’s actual burial at Tomis, rather than Rome, further demarcates the boundary of Augustus’ empire beyond which his earlier poetry soared.