Tlaxcala as a community and city played an interesting role in Mesoamerican history.

By Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank

Assistant Professor of Art History

Pepperdine University

Introduction

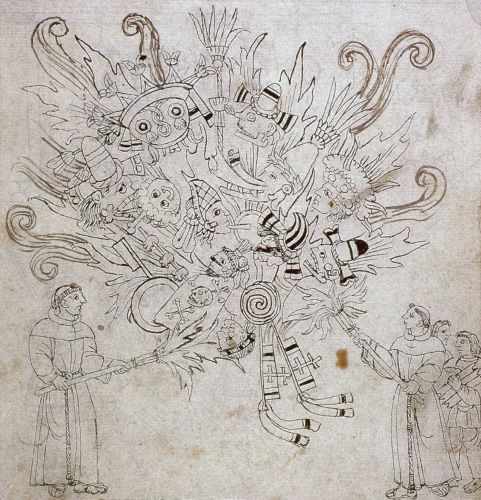

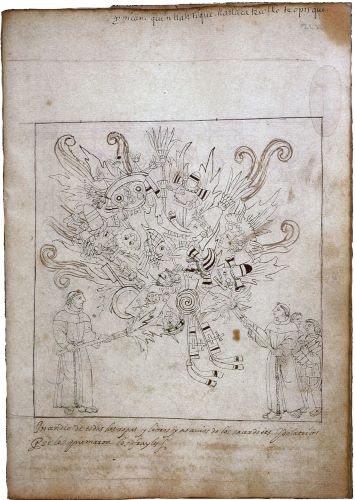

Two men hold long torches, aflame at one end, to a large mass of carefully depicted things that hover in the air, all of it encompassed by more flames curling outwards. Some of the bigger flames have even been emphasized with added brown ink. Looking closely at what these two men burn, we notice numerous heads—some human, others fantastic, as well as banners, shields, and other ornaments. The two men engaged in the act of burning are not the main focus of this drawing’s composition however—what they seek to destroy is. Less noticeable are two slightly smaller figures wedged into the right side.

The artist clearly wanted anyone looking at this drawing to focus on what is being burned: here, objects and materials associated with Mesoamerican divinities from Central Mexico, divinities who were worshipped prior to the Spanish invasion that began in 1519. We can make out one figure with a long, protruding bill or snout—this is the wind god, Ehecatl-Quetzalcoatl. A skeletal figure with an open mouth likely represents Mictlantecuhtli, Lord of the Underworld (Mictlan). A large figure at the top with goggle eyes is Tlaloc, the god of rain.

This drawing in ink is from the late 16th-century colonial era manuscript known as the Description of the City and Province of Tlaxcala, an important source for its discussion of the Spanish conquest of Mexico in 1521. The Description is composed of three “sections.”1 The initial section of more than 200 pages of text was written between 1581–84 by Diego Muñoz Camargo, a mestizo born in the region of Tlaxcala to a Spanish conquistador father and Indigenous mother (likely a noble Tlaxcalan woman). Two other sections are composed of more than 150 images drawn by unknown Indigenous artists who worked with Muñoz Camargo.

This scene of the bonfire has become the most reproduced image from Muñoz Camargo’s manuscript because it relates to what some art historians have called the war on images that occurred after the Spanish conquest. [2] In the drawing, two Franciscan missionaries—who were one of several groups directly responsible for the conversion of the Indigenous population to Christianity—are the ones who actively destroy the material culture of Indigenous peoples that they believed threatened their attempts at evangelization. They are identifiable as Franciscans by the outer garment (habit) they wear, complete with a knotted belt, and their haircut that involved shaving a bald spot at the top (tonsure).

Also of interest in this scene are the two young men behind one of the Franciscan friars: these are Tlaxcalan boys who have brought kindling for the fire. The artist shows them as active participants in the destruction of their own cultural heritage. Whether or not this was accurate, the image conveys that some Indigenous peoples willingly sided with missionaries to bring Christianity to the peoples of Mesoamerica, now part of the viceroyalty of New Spain controlled by the Spanish Crown. In fact, the Tlaxcalteca (the people of Tlaxcala) had sided with Spanish conquistadors against the Mexica—their arch enemies—and were the first Indigenous community to publicly embrace Christianity. This religious transformation and the acceptance of the conquerors’ religion is signaled here by the aid of the two young men in the destruction of the “old ways.”

Like the image visualizes, many objects associated with Indigenous religion and knowledge were burned or destroyed in what have been called “extirpation campaigns.” If you’ve ever wondered why so few prehispanic manuscripts survive today, it is because many of them ended up on bonfires. One Franciscan friar, Diego de Landa, in the Yucatán noted that Maya books were thought to contain nothing but “superstitions and falsehoods of the devil” and so he had them burned; he is estimated to have destroyed more than 5,000 objects (books among them) in a single bonfire.3 And he was not alone; these acts of iconoclasm are among the biggest in history.

The scene of the bonfire relates to power, conversion, and conquest—from one point of view—and trauma, resiliency, and identity from a very different perspective. Indigenous communities were resilient in the face of such destruction (often accompanied by waves of epidemics that decimated entire communities). Sometimes objects were hidden away for safeguarding. Others were buried beneath new Christian things erected atop. For some, the knowledge remained and was funneled into new visual expressions—radically transformed in appearance perhaps, but harnessing new media or technologies to encode Indigenous knowledge (such as sculptures using European visual modes). Some types of images even continued to flourish after the conquest, such as featherworking and mural painting.

Tlaxcala and Diego Muñoz Camargo’s Account

Tlaxcala as a community and city played an interesting role in Mesoamerican history and during the events of the conquest. The Tlaxcalteca had long managed to ward off Mexica (Aztec) imperial forces in the years before 1519. When Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés traveled from Veracruz inland to Tenochtitlan in 1519, he encountered the Tlaxcalteca, and described their city in his letters to the King of Spain as one of plentiful food, good buildings, and large in size. The Tlaxcalteca would decide to ally with Cortés and his men to defeat the Mexica, and were a major reason as to why the Spanish conquest was successful. Also, because Tlaxcala became one of the initial centers of Christian conversion by the Franciscans (who were the first group of Christian missionaries to arrive in New Spain), the Tlaxcalteca adopted Christianity early. As a result of their alliance with Spain, Tlaxcalan nobles intermarried with Spanish conquistadors.

Diego Muñoz Camargo was born of these two worlds as a mestizo, and he found ways to navigate his place and his communities’ places within these worlds. His noble status in both groups (the son of a conquistador and Tlaxcalan noble) afforded him privileges that other Indigenous peoples did not have. He was born into the first generation of mestizos after the conquest, and because of his parentage and position was given an education at a mission school in Mexico City, before returning to Tlaxcala and playing an important civic role. At one point, he even traveled to Spain to meet King Philip II and hand deliver him documents, including the Description. He wrote it in response to the 1577 Spanish royal survey, Instrucción y memoria, that asked different regions of Spain’s vast territories to describe the land and its resources, the cities and major buildings, and the makeup of its inhabitants. It is important to keep this context in mind when we look at the Description because it was mainly created for a Spanish courtly audience—not for the Tlaxcalteca.

The Description and the accompanying images sought to identify Tlaxcala’s important role in the conquest and conversion, and to champion the importance of the Tlaxcalteca’s place within colonial society. It traced the history of Tlaxcala until its establishment as a colonial city, and documented the Tlaxcalteca’s conversion process. In most of the images found in the Description, Tlaxcalteca appear with Spaniards, such as the two young Tlaxcalteca accompanying the Franciscan friars who burn the idols. He likely did this as an attempt to remind anyone reading the text of their alliance. It was undoubtedly important to Muñoz Camargo to maintain the noble privileges he had as a result of this union.

Idolatry

Christianity is also important in Muñoz Camargo’s text and the accompanying images. Besides the image of the burning of the idols, we see images of baptism, the cross, and missionary friars. One shows the first twelve Franciscans kneeling before a cross that is threatened by flying demons who have the faces of Mesoamerican deities, reinforcing the idea that the Mesoamerican divine was evil and worship of these deities was idolatrous. Just as he wanted to remind readers of the Spanish-Tlaxcalan alliance, Muñoz Camargo also wanted to convey that the Tlaxcalans were good Christians. Not long after the conquest, new buildings, such as the missionary complex of San Francisco de la Asunción de Nuestra Señora shown earlier, began to be built to serve as spaces for conversion and education. Muñoz Camargo describes the city in great detail in his account, both as a way to demonstrate its beauty and civic virtue, as well as to note the many Christian spaces and the activities that occur within them.

In both text and images, it is clear that Muñoz Camargo also wanted to demonstrate that the Tlaxcalteca had rid themselves of pagan worship of “idols.” Extirpation campaigns heavily targeted “idols” in Tlaxcala, which is indicated not only in the bonfire image in the Description but others that show the Franciscans in Tlaxcala hanging idolaters (people who worship idols).

The Spanish inscription that accompanies the image even describes idolatrous priests (“los sacerdotes idolátricos”) as the individuals who used the items being burned.

The text written in Nahuatl at the top of the page also states that here we are seeing the burning of teopixque or “caretakers of the gods,” further reinforcing the idea of these as idols and justifying the mass destruction of Mesoamerican religious materials. Both inscriptions further suggest that Muñoz Camargo wanted to clearly communicate to his Spanish audience that worship of Mesoamerican deities was unorthodox (here understood to mean non-Christian) and so needed to be rooted out and destroyed.

Between Worlds

Even though Muñoz Camargo described in detail Tlaxcala’s important role in the conquest and the Tlaxcalteca’s conversion to Christianity to demonstrate how they are both good allies and Christians, he was critical in his text of the Spanish destruction of Tlaxcala’s cultural heritage and the mistreatment of the Tlaxcalteca. His manuscript was an attempt to inform the Spanish King of these issues with the hope that the ruler could address these problems and hopefully gain additional privileges for the Tlaxcalteca from the Spanish Crown. While he was likely successful in the short term, eventually the Spanish Crown would reverse course and remove exemptions it had made for Tlaxcala in an attempt to increase profits for the Spanish Crown.4

Appendix

Endnotes

- Muñoz Camargo’s manuscript is sometimes referred to as the History of Tlaxcala (Historia de Tlaxcala), and the written part solely as the Description, and the two parts with images as Tlaxcala Calendar and Tlaxcala Codex. The Glasgow University Library has a useful discussion.

- See, for instance, Serge Gruzinski, Images at War: Mexico From Columbus to Blade Runner (1492–2019) (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2001).

- Diego de Landa, Yucatan before and after the Conquest (New York: Dover, 1978), p. 169.

- The Description remained in Spain until the later 18th century, and was eventually purchased by Dr. William Hunter and made its way to Scotland and eventually into the Glasgow University collections, where it remained largely unnoticed for a long time until the later 20th century.

Additional Resources

- Charles Gibson, Tlaxcala in the Sixteenth Century (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1967).

- Byron Hamann, “Producing Idols,” Latin American and Latinx Visual Culture 1, no. 1 (2019): pp. 19–43.

- Travis Barton Kranz, “Visual Persuasion: Sixteenth-Century Tlaxcalan Pictorials in Response to the Conquest of Mexico,” in The Conquest All Over Again: Nahuas and Zapotecs, Thinking, Writing, and Painting Spanish Colonialism, ed. Susan Schroeder (Eastbourne, UK, and Portland, OR: Sussex Academic Press, 2010).

- Diego de Landa, Yucatan before and after the Conquest (New York: Dover, 1978).

- Marilyn Miller, “Covert Mestizaje and the strategy of ‘passing’ in Diego Muñoz Camargo’s Historia de Tlaxcala,” Colonial Latin American Review 6 (June 1997): pp. 41–59.

- Barbara E. Mundy, “Extirpation of Idolatry and Sensory Experience in Sixteenth-Century Mexico,” in Sensational Religion: Sensory Cultures in Material Practice, ed. Sally M. Promey (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), pp. 515–35.

- Justyna Olko, Agnieszka Brylak, “Defending Local Autonomy and Facing Cultural Trauma: A Nahua Order against Idolatry, Tlaxcala, 1543,” Hispanic American Historical Review 1, 98 (4) (November 2018): pp. 573–604.

- David Tavarez, The Invisible War: Indigenous Devotions, Discipline, and Dissent in Colonial Mexico (Redwood City, CA, 2011).

- Eleanor Wake, “Codex Tlaxcala: new insights and new questions,” Estudios de Cultura Náhuatl 33 (2002): pp. 91–140.

Originally published by Smarthistory, 01.12.2023, under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license.