Justinian II’s reign stands as one of the most paradoxical episodes in Byzantine history, a period of artistic brilliance and political decay.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: The Emperor and His Vision of Divine Kingship

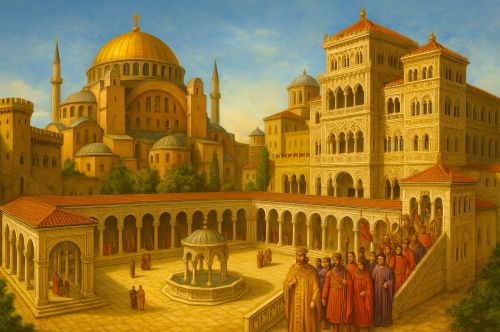

When Justinian II Rhinotmetos ascended the Byzantine throne in 685 CE, he inherited an empire battered by decades of war, plague, and loss. Yet he imagined himself as a second Justinian the Great, an emperor destined to restore the radiance of the Christian imperium through monumental architecture and imperial spectacle. His rule became a deliberate echo of the sixth century: grand projects, gilded churches, and a Great Palace refashioned to display divine favor. To Justinian II, the empire’s recovery would be seen not merely in territory or treasury, but in marble, mosaic, and gold. Architecture was theology made visible; his palaces and sanctuaries proclaimed the cosmic sovereignty of the basileus, an emperor ruling by God’s mandate.1

But what had once served as propaganda for his illustrious namesake became, under him, the engine of ruin. To sustain his lavish ambitions, Justinian II imposed crushing taxation on an already exhausted populace. His fiscal demands fell most heavily upon the provinces of Anatolia and the Balkans, which had only recently begun to recover from Arab and Slavic incursions. In the chroniclers’ accounts, his administration degenerated into coercion and extortion, administered by brutal officials such as Stephanus the Persian.2 The emperor’s palatial expansions and golden halls, adorned with Christ enthroned above the imperial image, were funded by an empire growing poorer and angrier with each new decree.3

What began as a vision of sacred kingship soon corroded into tyranny. By the late 690s, the splendor of Constantinople’s rebuilt palaces had become symbols of imperial excess, and the emperor’s obsession with magnificence estranged soldiers, clergy, and citizens alike. When the revolt of 695 CE erupted, it was not merely a political coup but a moral judgment against imperial arrogance.4 His mutilation and exile reflected a populace that had come to view its sovereign not as God’s chosen ruler but as a despot enthralled by his own reflection.

What follows examines Justinian II’s architectural program as a mirror of his political character, how palaces, churches, and ceremonial halls intended to embody divine authority instead revealed the moral and administrative fissures of the late seventh-century empire. It traces the intersection of aesthetics and autocracy, from the ideological symbolism of his buildings to the economic and social costs that destabilized his reign. In doing so, it argues that Justinian II’s mania for construction transformed Byzantine architecture into an instrument of domination whose brilliance could not conceal the decay beneath. His fall in 695 CE, and again in 711 CE after a vengeful return, demonstrates how imperial grandeur, when divorced from justice and restraint, becomes a monument to decline rather than glory.5

The Architectural Program: Palaces, Churches, and Imperial Imagery

Justinian II’s architectural program was conceived as a theater of divine kingship, where every marble wall and gilded dome became part of an imperial performance. The emperor’s building campaigns in Constantinople and beyond were meant not only to glorify God but to equate his rule with divine order. The Great Palace, already an intricate complex of ceremonial and administrative spaces, was expanded with new halls and sanctuaries that redefined the city’s imperial topography. Theophanes the Confessor records that Justinian II built or renovated several chambers, including the Triklinos of Justinian II and the Hall of the Augusteus, where golden mosaics depicted Christ enthroned above the emperor, an unmistakable image of celestial endorsement.6 The emperor’s architectural efforts, though steeped in theological symbolism, carried a political message: to remind the elite and the populace alike that imperial authority was sacrosanct and inseparable from divine will.

The emperor’s religious architecture reflected a similar fusion of piety and propaganda. Contemporary chroniclers and later architectural historians describe his dedication of churches to Christ and the Virgin, following the tradition of his sixth-century namesake. Among these were expansions of sanctuaries within the palace precinct and new foundations in suburban districts such as Blachernae and Daphni.7 These projects employed rich materials (porphyry columns, marble revetments, and shimmering gold tesserae) meant to evoke heavenly splendor on earth. As Cyril Mango observed, the decorative program of the period emphasized transcendence and imperial mediation between God and humankind, positioning the emperor as the axis between heaven and empire.8

Art historians have noted that Justinian II’s iconographic choices marked a significant evolution in Byzantine imperial imagery. Mosaics depicting Christ Pantokrator, now shown holding a Gospel rather than bestowing a blessing, began to appear in imperial contexts during his reign, a shift some scholars attribute to Justinian’s emphasis on divine law as the foundation of imperial legitimacy.9 The visual rhetoric of his palaces and churches thus paralleled his political aspirations: order, obedience, and hierarchy radiating outward from the emperor’s person.

Yet beneath the opulence lay anxiety. Architectural magnificence could project stability, but it could not conceal the fractures within the empire’s administration. By anchoring his legitimacy in visible splendor, Justinian II created an aesthetic of autocracy that demanded constant performance. Each new hall, church, and mosaic required more gold, more labor, more tribute. The glittering façades of Constantinople became a mirror of imperial insecurity, a ruler seeking permanence in stone while his subjects grew restless under the weight of his ambition.10

The Financial Machinery: Taxation and Extortion Under the Building Regime

The splendor of Justinian II’s architectural projects was sustained by a fiscal apparatus that pressed the empire’s economy to its limits. His ambitions demanded resources on a scale unmatched since the sixth century, yet the geopolitical and demographic conditions of the late seventh century were far less favorable. Arab conquests had stripped the empire of its richest provinces in Egypt and Syria, and the loss of these territories deprived Constantinople of essential revenues in grain, gold, and trade.11 To compensate, Justinian II and his administration imposed heavy levies on the remaining provinces, particularly in Asia Minor and the Balkans, where landowners and peasants alike bore the brunt of new taxes. Theophanes the Confessor describes how the emperor’s collectors enforced payment with brutality, extracting tribute under threat of imprisonment, mutilation, or death.12

Fiscal coercion was not new to the Byzantine system, but under Justinian II it acquired an intensity that contemporaries likened to tyranny. The emperor’s inner circle, including the notorious official Stephanus the Persian, became synonymous with corruption and violence. Theophanes recounts that Stephanus not only extorted money from the population but also plundered church properties, claiming divine sanction from the emperor himself.13 This blurred the boundary between imperial necessity and personal enrichment, undermining both the moral authority of the state and the legitimacy of its ruler. The ecclesiastical hierarchy, already uneasy with Justinian’s authoritarian tendencies, began to view his fiscal policies as sacrilege. The confiscation of church wealth, once a temporary measure during crises, became a standing practice to support construction and luxury at court.

Economic historians have traced how these policies disrupted local economies and strained the thematic system, the administrative and military structure that had been the backbone of Byzantine resilience since the Heraclian reforms. John Haldon notes that by overtaxing productive regions to fund his grandiose works, Justinian II weakened the very institutions that defended his empire.14 Peasants fled their lands to escape fiscal oppression, and soldiers, often paid in kind through grants of land, faced shortages that undermined their loyalty. As tax revenues fell despite higher rates, the emperor’s response was to demand even more, creating a spiral of exaction and resentment.

This fiscal crisis extended into the heart of the capital. In Constantinople, merchants and artisans were compelled to contribute to imperial projects, sometimes through forced labor. The city’s economy, dependent on imported grain and artisanal production, suffered under compulsory requisitions and declining trade confidence.15 Even the splendor of the Great Palace (its mosaics, marbles, and gilded vaults) became visible reminders of inequity, monuments built from the exhaustion of the populace. As the emperor’s architectural rhetoric exalted divine kingship, his subjects saw only extravagance purchased by suffering.

In the end, Justinian II’s financial policies eroded the social compact that had long bound ruler and ruled. The empire’s fiscal machine, once a pragmatic balance between state need and popular endurance, became a tool of imperial vanity. The emperor’s pursuit of eternal monuments produced only ephemeral power. His vision of architectural immortality demanded sacrifices his people could no longer bear, and the resulting discontent would soon ignite rebellion.16

Public Reaction and the Revolt of 695 CE

By the late 690s, the Byzantine capital had become a paradox of splendor and suffering. The newly adorned halls of the Great Palace glittered with gold mosaics and marble revetments, while the city beyond its walls sank under the weight of imperial taxation. Theophanes the Confessor describes how resentment spread across every class: soldiers unpaid, merchants overtaxed, and peasants dispossessed.17 Even the clergy, once stalwart defenders of imperial sanctity, began murmuring against the emperor’s impiety. The visual and ceremonial grandeur that had once awed the populace now provoked outrage. To the common citizens of Constantinople, Justinian II’s architectural opulence no longer symbolized divine kingship but divine mockery: a ruler cloaked in piety, yet deaf to the cries of his people.

Among the most alienated were the army and the administrative bureaucracy, the very pillars of imperial survival. Justinian II’s reforms, designed to centralize authority, weakened the autonomy of the provincial themes and alienated their commanders.18 Soldiers in the Anatolic and Thracesian themes, burdened by forced contributions and declining stipends, began to question their loyalty. The emperor’s insistence on collecting arrears even during military campaigns created a climate of quiet mutiny. According to Nikephoros’ Breviarium, units stationed near the capital were especially aggrieved by the emperor’s favoritism toward his palace guard, whose luxurious pay and exemptions became public scandal.19 The army’s disaffection would prove decisive when rebellion finally erupted.

The court itself reflected the corruption and fear pervading the empire. Stephanus the Persian, once tasked with fiscal administration, now acted as an enforcer of terror. Theophanes recounts episodes of torture, confiscation, and forced confessions orchestrated within the palace precincts.20 Even members of the imperial household and senate were subject to his cruelty, their wealth siphoned into the emperor’s endless projects. The palace, the architectural heart of Byzantine legitimacy, had become an instrument of intimidation. Ceremonies meant to glorify the emperor, such as the imperial adventus processions through the city, were met with uneasy silence rather than cheers. The gilded grandeur of the capital masked a polity on the verge of implosion.

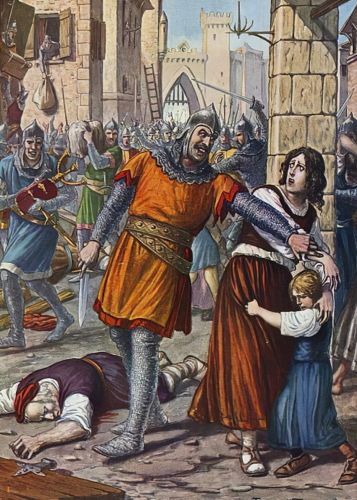

Public unrest reached a breaking point in 695 CE. A revolt led by Leontios, the strategos of the Theme of Hellas, capitalized on the widespread hatred of the emperor’s fiscal excesses and cruelty.21 The populace, driven by both hunger and humiliation, joined with the army in open insurrection. The rebels stormed the palace, and the emperor was seized, deposed, and subjected to the ritual mutilation that would mark him forever, nose cut off to render him unfit for rule. His epithet Rhinotmetos became the enduring symbol of a ruler undone by his own hubris. Theophanes notes that the people rejoiced at his downfall, viewing it not merely as a political act but as divine retribution for his sins against both God and man.22

The deposition of Justinian II revealed the fragility of autocracy when severed from moral legitimacy. His subjects’ hatred was not born of rebellion against empire itself but against its distortion, against an emperor who demanded worship but offered only oppression.23 The revolt reflected an ancient Byzantine understanding that the emperor ruled conditionally, sustained by a covenant of justice. When that covenant was broken, the divine mandate was believed to pass to another. The spectacle of Justinian’s fall, enacted within the very palace he had adorned with gold and Christological imagery, was therefore as symbolic as it was violent: the divine presence he had claimed to embody was now withdrawn.

In the aftermath, the empire entered a brief interlude of relief and introspection. Leontios, though himself later deposed, curtailed the extravagant projects and promised a return to moderation.24 Yet the memory of Justinian II’s first reign lingered in the public imagination, a cautionary tale of grandeur without governance. The walls of his unfinished palaces stood as mute witnesses to his overreach, monuments to a theology of power that had consumed its own maker.

The Return and Second Reign (705–711 CE): Tyranny Renewed

When Justinian II returned to the throne in 705 CE, aided by the Bulgar Khan Tervel, his restoration was heralded by a spectacle as grand as his earlier downfall had been brutal. Emerging from exile and disfigurement, he styled himself a ruler chosen anew by divine providence, parading through Constantinople in triumph beside his foreign ally.25 Yet beneath the gilded ceremony lay an emperor consumed by vengeance. The palaces and churches that had once symbolized renewal now became instruments of fear. Chroniclers record that Justinian ordered the execution or mutilation of all those implicated in his earlier deposition (senators, generals, and even common citizens) turning the capital into a theater of retribution.26 His second reign began not with reconstruction but with punishment, as the emperor sought to rebuild his authority on terror rather than consensus.

Once again, architecture became a medium of self-assertion. Justinian II resumed his building programs, restoring and expanding the Great Palace complex and commissioning further gilded halls to outshine the splendor of his first reign. Theophanes the Confessor notes that the emperor “raised new golden roofs and silver doors” within the palace precincts, embellishing his throne room with images of Christ in majesty, a calculated statement that divine sanction had returned.27 Yet these works, more ostentatious than before, drained the treasury and reignited resentment among the tax-paying classes. The emperor’s megalomania, reinforced by his obsession with sacred imagery, blurred the boundary between piety and delusion. His architecture of revenge, built upon the bones of his enemies, represented not renewal but regression, a grotesque echo of the glory he had once sought.

The brutality of his governance deepened the rift between the palace and the people. As fiscal burdens returned, so did the cycle of coercion and rebellion. Theophanes recounts that officials who hesitated to enforce the emperor’s commands were tortured or executed, while the countryside again suffered confiscations and forced levies to fund his extravagance.28 Even the church, briefly reconciled after his restoration, recoiled at his renewed tyranny. His persecution of clergy suspected of disloyalty and his arrogance toward the patriarchate alienated the spiritual legitimacy that had once underpinned imperial rule. The image of Christ enthroned above the emperor in mosaic now appeared, to contemporaries, less as a sign of divine favor than as an indictment of impiety.

By 711 CE, the empire’s tolerance for tyranny had reached its end. A revolt led by Philippikos Bardanes gathered support from disaffected soldiers and officials, echoing the uprising of 695 CE.29 The second fall of Justinian II unfolded with grim symmetry: the same opulence that had proclaimed his glory now framed his destruction. He was captured and executed, along with his wife and son, bringing a bloody end to the Heraclian dynasty. The palaces he had adorned with gold and marble stood silent, monuments to ambition unrestrained by reason. In the chronicles of Byzantine history, Justinian II remains a figure of tragic duality, an emperor whose vision of divine kingship dissolved into tyranny, and whose architectural grandeur became both his signature and his undoing.30

Fall and Execution: Architecture as a Mirror of Hubris

The final downfall of Justinian II in 711 CE was both political and symbolic. His capture and execution at the hands of the rebel forces under Bardanes marked more than the end of a dynasty; it represented the collapse of a vision of empire built on spectacle and coercion. Theophanes the Confessor, describing the event with grim precision, notes how the emperor who had once ruled from halls of gold was dragged from his sanctuary and beheaded without ceremony.31 The imagery is unmistakable: the ruler who sought immortality in marble and mosaic found only silence in the ruins of his ambition. His head, displayed in the Hippodrome, became the ultimate reversal of imperial iconography, a grotesque counter-image to the enthroned Christ that once hovered above his palace throne.

In the aftermath of his execution, the empire entered a period of introspection and instability. The architectural legacy of Justinian II endured as a cautionary landscape across Constantinople: unfinished palaces, abandoned workshops, and empty treasuries testified to the destructive cost of his grandeur.32 Chroniclers and theologians alike interpreted his fate as divine justice. Theophanes framed his demise as the judgment of God against pride, while later Byzantine writers invoked his reign as a warning of imperial hubris.33 In their accounts, architecture had ceased to be a vehicle of piety and become instead a monument to sin, the moment when sacred art was subverted by self-worship.

Yet historians such as George Ostrogorsky and John Haldon have emphasized that Justinian II’s failure was not merely moral but structural. His vast building schemes and punitive taxation exposed the fragility of the Byzantine fiscal system in the post-Heraclian age.34 By overcentralizing power and diverting resources to ceremonial display, he undermined the balance that had sustained the state after decades of military contraction. The very apparatus that had secured his father’s survival against the Arabs became an instrument of economic depletion and political isolation. When his legitimacy collapsed, no institution (neither army, church, nor senate) remained willing to defend him.

The ruins of Justinian II’s works, though largely erased or reabsorbed by later emperors, lingered in memory as emblems of folly.35 The Great Palace, stripped of its former glory, would continue to serve as the ceremonial core of Byzantine power for centuries, yet its mosaics and chapels bore traces of his excess. Later emperors such as Leo III and Constantine V learned a harsh lesson from his fall: that magnificence could not replace prudence, and that the divine right of kingship demanded restraint as well as radiance. The architectural remains of Justinian II thus formed an unspoken moral archive, a silent dialogue between stone and empire on the perils of absolute ambition.

Conclusion: The Architecture of Decline

Justinian II’s reign stands as one of the most paradoxical episodes in Byzantine history, a period of artistic brilliance and political decay. His architectural vision was born from an earnest, if distorted, conviction that the emperor embodied divine authority on earth. The palaces, chapels, and mosaics he commissioned sought to manifest this theology in tangible form, binding heaven to empire through marble and gold.36 Yet, as Theophanes the Confessor and later historians attest, the same monuments that proclaimed his sacred kingship also revealed his detachment from human suffering. The visual splendor of his empire was inseparable from its moral corrosion: the emperor who sought to build paradise in Constantinople instead constructed the stage for his own undoing.

In retrospect, the tragedy of Justinian II lies not merely in his cruelty or extravagance, but in his failure to understand the limits of empire itself. Byzantine power had always rested upon a delicate equilibrium, between ruler and ruled, between faith and pragmatism, between the material and the divine.37 Justinian’s unrestrained pursuit of monumental glory shattered that balance. His architecture transformed from a language of devotion into one of domination, alienating the very subjects whose labor sustained his reign. The collapse of his rule thus revealed a fundamental truth about the Byzantine world: imperial magnificence, when untempered by humility and justice, could no longer sustain belief in the emperor’s divine mandate.

The legacy of Justinian II endured long after his death, etched not only in chronicles but in the architectural memory of Byzantium. Later emperors approached construction with greater caution, mindful that even sacred beauty could become an idol of pride.38 His fate echoed across the centuries as a warning, an emperor who mistook grandeur for legitimacy, and who found in the ruins of his palaces the measure of his failure. In the long arc of Byzantine history, Justinian II remains both creator and cautionary figure: a ruler whose vision of eternity collapsed under the weight of its own splendor.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Theophanes the Confessor, Chronographia, ed. C. de Boor (Leipzig: Teubner, 1883–85).

- Nikephoros, Breviarium Historicum, ed. C. de Boer (Leiden: Brill, 1880).

- Cyril Mango, The Art of the Byzantine Empire, 312–1453 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1972).

- John Haldon, Byzantium in the Seventh Century: The Transformation of a Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990).

- George Ostrogorsky, History of the Byzantine State (Oxford: Blackwell, 1969).

- Theophanes the Confessor, Chronographia, 372–374.

- Nikephoros, Breviarium Historicum, 56–58.

- Mango, The Art of the Byzantine Empire, 89–92.

- Jonathan Bardill, Brickstamps of Constantinople (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 154–157.

- Haldon, Byzantium in the Seventh Century, 217–220.

- Ostrogorsky, History of the Byzantine State, 119–123.

- Theophanes the Confessor, Chronographia, 374–375.

- Nikephoros, Breviarium Historicum, 59.

- Haldon, Byzantium in the Seventh Century, 228–231.

- Jonathan Shepard and Simon Franklin, Byzantine Diplomacy (Aldershot: Variorum, 1990), 94–96.

- Mango, The Art of the Byzantine Empire, 101–103.

- Theophanes the Confessor, Chronographia, 376–377.

- Haldon, Byzantium in the Seventh Century, 236–239.

- Nikephoros, Breviarium Historicum, 62–63.

- Theophanes the Confessor, Chronographia, 378–379.

- Ostrogorsky, History of the Byzantine State, 126–128.

- Theophanes the Confessor, Chronographia, 380.

- Mango, The Art of the Byzantine Empire, 106–108.

- Bardill, Brickstamps of Constantinople, 160–162.

- Ostrogorsky, History of the Byzantine State, 128–131.

- Nikephoros, Breviarium Historicum, 64–65.

- Theophanes the Confessor, Chronographia, 382–384.

- Haldon, Byzantium in the Seventh Century, 241–244.

- Theophanes the Confessor, Chronographia, 385–386.

- Bardill, Brickstamps of Constantinople, 164–166.

- Theophanes the Confessor, Chronographia, 386–387.

- Mango, The Art of the Byzantine Empire, 110–112.

- Theophanes the Confessor, Chronographia, 388; see also Ostrogorsky, History of the Byzantine State, 132.

- Haldon, Byzantium in the Seventh Century, 246–249.

- Bardill, Brickstamps of Constantinople, 167–169.

- Theophanes the Confessor, Chronographia, 389–390.

- Haldon, Byzantium in the Seventh Century, 250–252.

- Mango, The Art of the Byzantine Empire, 113–115.

Bibliography

- Bardill, Jonathan. Brickstamps of Constantinople. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Haldon, John. Byzantium in the Seventh Century: The Transformation of a Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

- Mango, Cyril. The Art of the Byzantine Empire, 312–1453. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1972.

- Nikephoros. Breviarium Historicum. Edited by C. de Boer. Leiden: Brill, 1880.

- Ostrogorsky, George. History of the Byzantine State. Oxford: Blackwell, 1969.

- Shepard, Jonathan, and Simon Franklin. Byzantine Diplomacy. Aldershot: Variorum, 1990.

- Theophanes the Confessor. Chronographia. Edited by C. de Boor. Leipzig: Teubner, 1883–85.

Originally published by Brewminate, 11.04.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.