Babylonian astronomy cannot be fully understood if confined to the history of science. It was, fundamentally, a socio-political technology.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Astronomy Beyond the Heavens

When most people think of ancient astronomy, they imagine a priest or scholar scanning the night sky for omens, tracing constellations in the service of myth or religion. While this image captures part of the truth, it obscures another reality: in ancient Babylonia, astronomical observation was a tool of administrative precision, woven deeply into the economic machinery of the state. The Babylonians did not separate cosmology from governance. Stars, planets, and their cycles provided a temporal framework for agriculture, labor, and taxation. In effect, the heavens became an imperial ledger, where celestial events marked deadlines for earthly obligations.1

This fusion of astronomy and administration was neither incidental nor purely ceremonial. The Babylonian state relied on agricultural surplus to maintain temples, armies, and urban life, and surplus itself depended on accurate seasonal forecasting. The cycles of planting and harvest were vulnerable to climatic shifts, but the regular motions of celestial bodies offered a reliable, repeatable guide. By codifying these observations into standardized tables and omen lists, Babylonian scholars created a system where the appearance of a star could trigger the mobilization of labor or the collection of grain levies.

The Roots of Babylonian Astronomical Practice

From Omens to Prediction

Babylonian astronomy emerged from a much older tradition of celestial divination. As early as the Old Babylonian period (c. 1800 BCE), omen texts such as Enūma Anu Enlil linked the risings and settings of stars, the phases of the moon, and the positions of planets to terrestrial events.2 These associations were framed in the language of divine communication: eclipses might signal the downfall of a king, while unusual planetary alignments could warn of famine.

Over time, however, the scribes of Babylon refined their methods, shifting from qualitative interpretation to quantitative prediction. By the Neo-Babylonian period (626–539 BCE), astronomers had compiled systematic records of planetary motions and star risings over centuries. These records enabled them to anticipate celestial events with increasing accuracy. The act of prediction itself transformed astronomy from a reactive art into a proactive administrative instrument.

The Zodiac as a Tool of Measurement

By the late first millennium BCE, Babylonian scholars had formalized the zodiac into twelve equal divisions along the ecliptic, each associated with a constellation.3 While later Greek and Roman astrology would frame the zodiac primarily as a system of personal horoscopes, its Babylonian antecedent was tied to the calendar and the seasonal cycle. Each zodiacal sign served as a temporal marker, anchoring the timing of agricultural work and state obligations.

Celestial Calendars and Agricultural Planning

The Heliacal Rising of Stars

One of the most important astronomical techniques in Babylonia was the tracking of heliacal risings, the first visible appearance of a star or constellation just before sunrise. The heliacal rising of the star Sirius (known to the Babylonians as Kak-si-di) was associated with the onset of seasonal flooding in some Mesopotamian river systems, though its agricultural significance varied by region.4 More broadly, such risings were used to signal planting or harvesting windows.

For example, the reappearance of certain constellations after a period of invisibility could mark the transition between seasons, prompting farmers to sow barley or prepare irrigation channels. Because these stellar events were unaffected by local weather anomalies, they provided a more stable guide than observation of environmental cues alone.

Agricultural Work and Administrative Deadlines

The same celestial markers that guided planting also determined the timing of tax collection. In temple and palace archives, references survive to grain deliveries or labor corvée obligations tied to specific months or astronomical events.5 A star’s rising might not only indicate when fields should be harvested, but also when tenant farmers were expected to deliver their share to the temple granaries. In this way, astronomy functioned as a binding schedule, aligning agricultural labor with the logistical needs of the state.

Taxation and the Political Uses of Astronomy

The Temple Economy

In Babylonia, temples were not merely places of worship but also economic hubs that controlled large tracts of agricultural land. The temple’s role in storing and redistributing grain made the timing of collections critical. By fixing these moments to celestial events, administrators could synchronize rural production with urban consumption, ensuring a steady flow of resources to support craftsmen, soldiers, and priestly elites.6

Temple astronomers thus had dual responsibilities: to interpret the will of the gods and to keep the machinery of economic redistribution running smoothly. The same priest who recorded the position of Jupiter might also oversee the dispatch of tax collectors into the countryside, armed with a timetable rooted in the heavens.

Astronomy as Imperial Order

The state-level adoption of astronomical timekeeping also served a political function. By embedding administrative practice in the authority of the cosmos, rulers could present their economic demands as extensions of divine law. When tax deadlines coincided with the rising of a sacred star, the obligation carried not only legal weight but also religious sanction. In a society where the king was seen as the earthly representative of the gods, this alignment reinforced the legitimacy of both celestial and terrestrial authority.7

Knowledge, Standardization, and the Scholar’s Role

The Astronomical Diaries

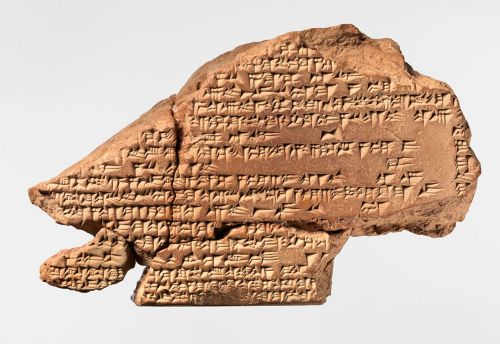

One of the most significant sources for our understanding of Babylonian astronomy is the corpus of Astronomical Diaries, clay tablets that record daily and monthly observations of the moon, planets, weather, and market prices.8 These diaries reveal how deeply intertwined celestial and economic information had become. Market fluctuations in barley or dates are recorded alongside eclipses and planetary conjunctions, suggesting that scholars viewed the economy as part of a broader cosmic system.

Training and Transmission

The scribal tradition that sustained this system was highly specialized. Apprentices learned not only to read and write cuneiform but also to calculate planetary positions and interpret seasonal star movements. This knowledge was transmitted within families and temple schools, creating an elite class of scholar-administrators whose authority rested on their mastery of both celestial mechanics and economic management.9

Conclusion: The Sky as a Mechanism of Governance

Babylonian astronomy cannot be fully understood if confined to the history of science. It was, fundamentally, a socio-political technology, one that allowed the state to regulate time, labor, and resources with remarkable precision. By tying the cycles of the heavens to the cycles of the fields and the treasury, Babylonian rulers created a form of governance that was both practical and symbolic.

This legacy endured. Later cultures, from the Hellenistic kingdoms to Islamic caliphates, inherited Babylonian astronomical methods, adapting them to their own administrative systems. The idea that the movement of the heavens could dictate the rhythms of earthly life persisted long after the fall of the Babylonian empire. In the end, the Babylonians remind us that the stars have never belonged only to poets and dreamers; they have also belonged to accountants, tax collectors, and kings.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Francesca Rochberg, The Heavenly Writing: Divination, Horoscopy, and Astronomy in Mesopotamian Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 6–9.

- Hermann Hunger and David Pingree, Astral Sciences in Mesopotamia (Leiden: Brill, 1999), 13–15.

- Rochberg, The Heavenly Writing, 140–143.

- John M. Steele, Observations and Predictions of Eclipse Times by Early Astronomers (Dordrecht: Springer, 2000), 21–24.

- Marc Van De Mieroop, A History of the Ancient Near East (Oxford: Blackwell, 2015), 210–212.

- Michael Jursa, “The Babylonian Economy in the First Millennium BC,” in The Babylonian World, ed. Gwendolyn Leick (New York: Routledge, 2007), 219–221.

- Rochberg, The Heavenly Writing, 165–167.

- Hermann Hunger, Astronomical Diaries and Related Texts from Babylonia, Vol. I (Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1988), xiii–xvi.

- Hunger and Pingree, Astral Sciences in Mesopotamia, 45–48.

Bibliography

- Hunger, Hermann. Astronomical Diaries and Related Texts from Babylonia. Vol. I. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1988.

- Hunger, Hermann, and David Pingree. Astral Sciences in Mesopotamia. Leiden: Brill, 1999.

- Jursa, Michael. “The Babylonian Economy in the First Millennium BC.” In The Babylonian World, edited by Gwendolyn Leick, 210–227. New York: Routledge, 2007.

- Rochberg, Francesca. The Heavenly Writing: Divination, Horoscopy, and Astronomy in Mesopotamian Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Steele, John M. Observations and Predictions of Eclipse Times by Early Astronomers. Dordrecht: Springer, 2000.

- Van De Mieroop, Marc. A History of the Ancient Near East. Oxford: Blackwell, 2015.

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.13.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.