The evangelical emphasis on biblical authority and personal conversion created a volatile mixture. It could be invoked to sanctify existing hierarchies or to undermine them.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: A Gospel of Liberty, A Theology of Bondage

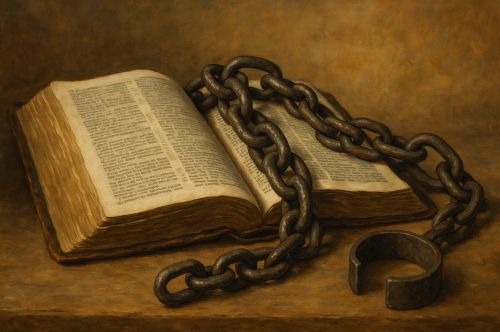

From the sixteenth to the nineteenth century, evangelicalism became one of the most dynamic forces shaping the Atlantic world. Preachers, missionaries, and reformers invoked the authority of Scripture to transform societies and reorder moral life. Yet evangelicalism was never unified in its response to the most pressing moral crisis of the age: human bondage. For some, the Bible sanctified slavery as an institution woven into divine order. For others, the same Bible proclaimed freedom and equality before God, demanding abolition.

The tension was not incidental. Evangelical religion, with its emphasis on the authority of Scripture, the immediacy of conversion, and the moral transformation of society, could be wielded on both sides of the debate. The history of evangelicalism and slavery reveals not a linear path toward freedom but a contested struggle in which theology, culture, and economics intertwined in complex and often contradictory ways.

Early Evangelical Encounters with Slavery

In the sixteenth century, as European powers expanded across the Atlantic, missionaries confronted the realities of colonization and enslavement. Catholic orders such as the Jesuits and Dominicans debated the moral legitimacy of enslaving Indigenous peoples. Bartolomé de las Casas famously condemned the enslavement of Native Americans, though he controversially suggested African labor as an alternative, a position he later repudiated.1

By the seventeenth century, Protestant missionaries entered the Atlantic world. Evangelical movements within Anglicanism began to take root in colonies, particularly in the Caribbean. Some missionaries baptized enslaved Africans and preached that they, too, were souls equal before God. Yet many planters resisted, fearing that Christian baptism might imply manumission. To allay these concerns, missionaries often reassured masters that baptism did not change civil status.2 In this way, early evangelicalism frequently accommodated slavery, even as it proclaimed spiritual equality.

The Evangelical Awakening and Ambiguities of the Eighteenth Century

The evangelical revivals of the eighteenth century, often termed the First Great Awakening, carried religion directly into the lives of ordinary men and women. Itinerant preachers such as George Whitefield and John Wesley electrified audiences with appeals to personal conversion. Their messages, however, diverged sharply on slavery.

Whitefield, despite his rhetoric of spiritual freedom, actively promoted slavery in Georgia, lobbying for the legalization of enslaved labor to sustain his orphanage. His defense of slavery rested on paternalistic grounds: that Africans would receive Christian instruction under bondage.3 Wesley, in contrast, condemned slavery as “the sum of all villainies,” drawing on both scriptural and moral reasoning to denounce the trade and the institution.4 Evangelicalism was therefore a fractured house. Its theology of the new birth could inspire both submission and rebellion, both acquiescence to bondage and its rejection.

African converts often perceived the radicalism within evangelical preaching more clearly than their white counterparts. The message that “in Christ there is neither bond nor free” provided spiritual grounds for resistance. Enslaved preachers in the Americas and the Caribbean infused evangelical language with liberationist meanings, sometimes sparking revivals that unsettled the social order. Evangelicalism could be co-opted by slaveholders, but it could not be contained by them.

Evangelicals and the Abolitionist Movement

By the late eighteenth century, evangelical conviction became one of the driving forces of abolitionism. In Britain, the Clapham Sect, a group of evangelical Anglicans including William Wilberforce, championed the abolition of the slave trade. Their appeals blended biblical morality with humanitarian sentiment, mobilizing popular opinion and influencing Parliament to end the trade in 1807.5

In America, figures such as Jonathan Edwards the Younger and Charles Finney drew upon evangelical theology to call for immediate abolition. Evangelical abolitionists emphasized the personal sinfulness of slaveholding, insisting that true conversion required repentance not only of private vices but also of systemic injustices. Their activism linked revivalism with reform, creating a moral synergy that shaped the antebellum era.

Yet even within abolitionist circles, tensions remained. Evangelical appeals to personal morality sometimes obscured the structural and economic dimensions of slavery. The focus on individual conversion could inadvertently undercut collective political action. Nevertheless, evangelical energy was crucial in sustaining the abolitionist cause, providing both the rhetoric and the moral fervor that fueled campaigns on both sides of the Atlantic.

The Evangelical Defense of Slavery in America

If evangelicalism produced abolitionists, it also armed defenders of slavery with theological arguments. In the American South, proslavery theologians cited both Old and New Testaments, pointing to the patriarchs, the Mosaic law, and the Pauline epistles to claim divine sanction for the institution. Preachers insisted that slavery was not only compatible with Christianity but integral to it, preserving order in a fallen world.6

Evangelical churches became divided along sectional lines. Baptists, Methodists, and Presbyterians all fractured in the 1840s and 1850s over the issue of slaveholding. Southern churches entrenched themselves as defenders of slavery, casting it as part of a providential design. Northern counterparts increasingly aligned with abolition. The schisms revealed that evangelicalism was not a single moral compass but a contested arena where scripture could be read in radically different ways.

Enslaved people themselves, however, often heard a different gospel. In secret “hush harbor” meetings, they drew on evangelical preaching to sustain hope and resist subjugation. The message of spiritual freedom, interpreted through the lens of their suffering, became a source of resilience and quiet defiance. Evangelicalism in the South was thus bifurcated: a theology of control for masters, a theology of liberation for slaves.

Nineteenth-Century Transformations and the End of Slavery

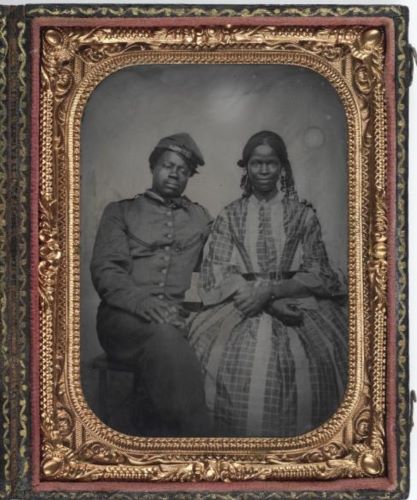

The nineteenth century saw the culmination of evangelical struggles over slavery. In Britain, evangelical abolitionists celebrated the end of slavery in the colonies in 1833 as a triumph of Christian conscience. In America, the Civil War became the crucible in which the evangelical debate reached its violent resolution. Northern preachers portrayed the conflict as divine judgment upon the sin of slavery, while Southern ministers insisted they fought to preserve a godly order.

After emancipation, evangelical churches played crucial roles in shaping Black life in the United States. Freedmen’s churches became centers of community, education, and political organization. Evangelical religion, once complicit in justifying bondage, now provided spiritual infrastructure for freedom. Yet the legacy of division endured. The fractures over slavery left scars in denominational life and revealed the malleability of evangelical theology under the pressures of economics and culture.

Conclusion: Evangelicalism’s Double Legacy

The history of evangelicalism and slavery from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century is not a tale of simple progress from complicity to liberation. It is instead a story of profound ambiguity. Evangelical religion baptized slaves while assuring masters of their rights. It justified bondage even as it inspired abolition. It divided churches, yet sustained enslaved communities with hope.

The evangelical emphasis on biblical authority and personal conversion created a volatile mixture. It could be invoked to sanctify existing hierarchies or to undermine them. The struggle over slavery thus reveals the double legacy of evangelicalism: a gospel of submission and a gospel of freedom, bound together in the same scriptural texts and preached from the same pulpits. To study this history is to confront the enduring capacity of religion to serve both power and resistance, both oppression and liberation.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Bartolomé de las Casas, A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies, trans. Nigel Griffin (London: Penguin, 1992), 43–47.

- Katharine Gerbner, Christian Slavery: Conversion and Race in the Protestant Atlantic World (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018), 64–68.

- Thomas S. Kidd, George Whitefield: America’s Spiritual Founding Father (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 213–217.

- John Wesley, Thoughts upon Slavery (London, 1774), 5.

- John Wolffe, The Expansion of Evangelicalism: The Age of Wilberforce, More, Chalmers and Finney (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 2006), 85–92.

- Mark A. Noll, The Civil War as a Theological Crisis (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 42–48.

Bibliography

- de las Casas, Bartolomé. A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies. Translated by Nigel Griffin. London: Penguin, 1992.

- Gerbner, Katharine. Christian Slavery: Conversion and Race in the Protestant Atlantic World. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018.

- Kidd, Thomas S. George Whitefield: America’s Spiritual Founding Father. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014.

- Noll, Mark A. The Civil War as a Theological Crisis. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006.

- Wesley, John. Thoughts upon Slavery. London, 1774.

- Wolffe, John. The Expansion of Evangelicalism: The Age of Wilberforce, More, Chalmers and Finney. Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 2006.

Originally published by Brewminate, 09.05.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.