Children were overused, paid less, and forced to work in unhealthy environments.

By Zuzana Lukáčová

PhD Candidate in English Language and Anglophonic Cultures

University of Presov

Abstract

The Victorian era is a major area of interest within the field of history. The main objective of the paper is to investigate this period as a key part of the history of Great Britain. The aim of this investigation is to develop an understanding and clarify several aspects of culture and everyday life in the Victorian period. The paper is divided into two chapters which map the Victorian Era from the onset of Queen Victoria in the fields of education, school system and child labour. In addition, the paper intends to determine the extent to which child labour affected everyday life of Victorian children and to point out the influence of social classes upon education.

Introduction

The Victorian era plays an important role in the history of Great Britain. This historical period is increasingly recognised as a serious, worldwide public historical concern and it is a major area of interest within the field of history in general. This period is characterized by progression and innovation which had a significant impact on the following growth of the country.

The paper aims to extend our knowledge of the period. It offers some important insights into different aspect of the period, especially education, school system and the problem of child labour. Furthermore, it attempts to show the authentic picture of the period supported by the use of contemporary documents and literature, e.g. In Darkest England and the Way Out by William Booth, Sibyl, or The Two Nations by Benjamin Disraeli.

A considerable amount of literature (as well as electronic sources) has been published on this topic by many researchers and authors using historical sources (documents, letters, authentic diaries, et cetera), such as Paxton Price, Warren C. Robinson, Emma Griffin, Liza Picard and many others. In the literature on this topic, the relative importance of child labour has been subject to considerable debate. Questions have been raised about the safety of child labour in the Victorian period. The paper points out the extend to which child labour affected everyday life of Victorian children as well as the influence of different social classes upon education

The paper has been organised in the following way. The overall structure takes the form of two chapters. Chapter one begins by laying out the concept of education and school system in the Victorian period. The second chapter is concerned with everyday life, especially child labour and its impact on everyday life of Victorian children.

Education and the School System

The spirit of the British Empire was noticeable not only at political and economical level, but also in the area of culture. In 1851, Queen Victoria opened “the Great Exhibition of the Industry of all Nations” in the Crystal Palace in London which reflected progression, innovation and development of the country. In addition, McDowall (1989) demonstrates in his book An Illustrated History of Britain that no other nation at that time managed to produce as much as Great Britain. By the year 1850, Britain had produced more iron than all other nations together. This suggests that Great Britain had undergone changes in different areas.

With Queen Victoria on the throne the situation in education was about to change. During her reign the school system was undergoing many reforms. West (1996) investigated the rate of school attendance along with the rate of population growth. His chart (table 1) describes the growth in public schooling. The average annual growth rate of population was about double the growth rate of population between 1818 and 1858. The evidence from this study shows that education became more accessible among Victorian children.

Boys from middle class attended charged public schools. The purpose of these schools was not only to provide a quality education, but also to teach young boys independence. Later on, most of the former students became officers of colonial administration, military and government management (McDowall 1989). Apart from public schools, children also attended church schools, jewish schools and schools for girls.

One of the schools that provided education for the poorest children was Central London District school for Pauper Children known as the “Monster School” because of the number of the students attending the school (around 1,000). Picard (2015) draws our attention to church schools that followed so-called “Lancaster system” according to which the smartest student was supposed to teach his peers. In 1846, the system was changed when only trained teachers were allowed to teach. The Jewish school in London was established in 1817. In 1822, there were 600 students attending the school. Later on, in 1870 it was 2,400 students and with high probability it was the largest school in the world.

Requirements for education differed. How important education was considered to be also dependend on gender. Furthermore, boys and girls had different opportunities for studying, especially at universities.

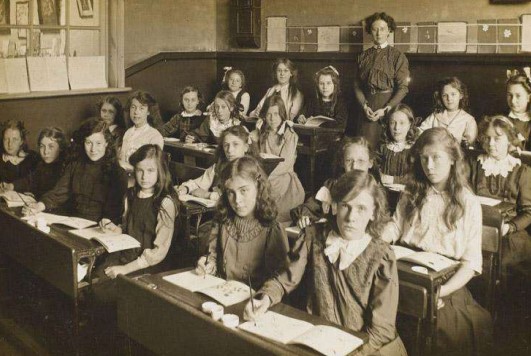

In comparison to a man, the higher class did not consider education to be important for a woman. After a marriage, a woman was expected to take care of her family, give birth, entertain her husband’s guests and look presentable. Flower arranging, singing and playing the piano were beneficial. If a woman could not find a man, her objective was to take care of her parents or children of her siblings. Sometimes she had to work, most of the time as a teacher or governess. An increased interest in educating women was going hand in hand with an effort to grant the right of women to vote. In 1848, Queen’s College in Harley Street in London was established. Ten years later another Cheltenham Ladie’s College was founded. Later on, other public schools for girls were founded (figure 1). In 1898, there were already ninety schools for girls (Picard, 2015). The increased number of schools for girls suggests that the situation was about to change.

Some of the children were apprentices that were taught by their master. According to Picard (2015), the master provided the apprentices with accommodation and clothes. The apprenticeship lasted usually seven years during which the apprentices were not given any money, however, some of them were paid right before they finished the apprenticeship. On the other hand, most of the children taken from parish workhouses were overused for the profit and not treated well. The evidence of this can be seen in a case of flogging an apprentice published in Reynold’s Newspaper on 20th September 1896 (figure 2).

The way schools were being established was about to change. Since 1870 local authorities were obliged to establish schools at the financial expense of local taxpayers. These organs expected the children to have regular school attendance. In the next twenty years, other schools were founded. Between 1870 and 1891, two education acts came into effect. The result was the compulsory school attendance up to the age of thirteen (McDowall, 1989).

Despite the compulsory school attendance, children who were smart and achieved the stated learning standard could finish the school earlier. According to statistics taken in 1900, illiteracy decreased to only five percent in comparison to thirty percent illiteracy of men and forty percent illiteracy of women in 1850. In fact, for the first time the government took control over spreading education. Until then the government only provided religious societies with financial grants for school provision. Robert Lowe, a liberal politician declared: “From the moment you entrust the masses with power, their education becomes an imperative necessity.” (Morgan, 2006, p. 325). Furthermore, the importance of education was comfired by a member of the parliament who was behind many school reforms, W.E. Forster. In February 1870, he pointed to other reasons why the parliament should intervene to the field of education and school system:

We must not delay… Upon the speedy provision of elementary education depends our industrial prosperity. It is of no use trying to give technical teaching to our artisans without elementary education… if we leave our workfolk any longer unskilled… they will become over-matched in the competition of the world (Morgan, 2006, p. 325)

Therefore, it is possible to conclude that the government as well as the parliament were aware of the importance of education and undertook measures needed for its evolvement. This can be also seen in Morgan’s (2006) conclusion that by the year 1900, there were 2,500 new schools in England and Wales. One of the principals announced that between 1882 and 1900 boys had become “much more docile; insubordination, then endemic, now almost unknown… Truancy almost extinct. Personal cleanliness greatly improved; verminous cases among boys rare, but among girls almost universal, due to their long hair.” (p. 325)

Additionally, according to Price (n.d.), minimal truancy and strict discipline were, to a certain extend, a result of physical punishment. Teachers used a birch cane with which boys were beaten on their back and girls on their legs or hands. The reason of the punishment was laziness, disobedience, truancy. Even the younger children from the age of five to ten years were often physically punished. Children who had some difficulties with learning and were slower than the rest had to wear “the shameful dunce hats” and had to sit in the corner of the classroom for more than one hour. This “method” was humiliating and did not help children to catch up. Children with learning disabilities were often considered to be lazy or non-strenuous. Children were made to write with right hand only, otherwise they were punished. A typical school day started with an introductory meeting. A lesson started at nine o’clock in the morning and finished at twelve o’clock. During lunchtime children went back home to eat, so did their fathers. The first lesson in the afternoon started at two o’clock and finished at five o’clock.

School equipment in the Victorian era was different from the one available nowadays. Due to financial expenses a slate was preferred to be written on over paper which was much more expensive. For writing they used special pencils. After being checked by the teacher, students erased the slate and started to write again. Students were expected to remember everything important. The youngest children (from five to six years) practised writing in sand trays. The older children used a dip pen with black ink for writing in a book. For Mathematics teachers used an Abacus which was an older version of a calculator (Price, n.d.).

Without doubt, universities were also of great importance. So-called “redbrick” universities were built in the new industrial centres. The older universities were built of stone (like Cambridge and Oxford). In these new “redbrick” universities students studied science and technology as they could work later in the British industry (McDowall, 1989). In general, studying at a university followed strict rules. Cambridge and Oxford Universities required the following: an applicant had to be a single man and a member of an Anglican church. In 1832, the University of Durham was established. In 1836, some of the smaller colleges were grouped together and created London University. In 1851, Owens College in Manchester and in 1900 Birmingham University were founded. Since 1878 London University allowed women to study (only in Bedford College and The Royal Holloway College). Hovewer, women had been rejected by Cambridge and Oxford up to the 20th century (Picard, 2016).

As for the school system in Scotland, McDowall (1989) notes that since the Reformation there had been a state school system in Scotland. Four universities were founded, three of which had been rooted in medieval times. On the contrary, education in Wales began to spread mostly since the mid-19th century partially because of the patriotic reasons. By mid-century, in Wales there was a university in Lampeter (1822) and a smaller university college Trinity (1848).

It is possible to conclude that Victorian education and school system were undergoing many changes and reforms during the Victorian period as a result of attention being paid to the school system.

Child Labor

Poverty was part of life for many Victorian people. It was reflected in everyday life. Since industrialisation called for cheap labour, children were forced to work from very young age in working environmnent that negatively influenced their health. People viewed poverty differently. On one hand, there were those who were empathetic and sympathised with the poor, on the other hand those who considered poverty to be a sin.

One of those who pointed out the struggle of the poorest and criticised social conditions was a politician and a writer Benjamin Disraeli. In his novel Sybil, published in 1845, he criticised British society which was, according to him, divided into two nations – the nation of the poor and the nation of the rich (Morgan, 2006). In this novel Benjamin Disraeli shows symphaty for the poor which can be seen in the passage: “Well, for my part,” said Mr. Berners, ”I do not like your suburban dinners. You always get something you can’t eat, and cursed bad wine.” “I rather like bad wine,” said Mr. Mountchesney; “one gets bored with good vine.” (Disraeli, 1845, p. 5). Another author who showed great concern for the poverty was William Booth. He was a founder of a movement “Salvation Army” which was created to fight against poverty. In his book In Darkest England and the Way Out he emphasised the fact that while British called Africa “dark continent”, much “darker areas” were situated in their home towns (McDowall, 1989).

In comparison to those who sympathised with the poor were those who considered poverty to be a sin, for instance Presbyterians and Methodists. Their opinions were vindicated by claiming that prosperity, wealth and success were the proof that an individual was chosen by God. On the contrary, poverty was the evidence of the opposite (Robinson, 2002).

Since the poor families needed every penny, children coming from these families (but also orphans) had to work from very young age. Therefore, child labour became the reality of the period and affected everyday life, including education.

According to statistics taken in 1840, only twenty percent of children in London were educated. This percentage increased by 1860 when around half of children from five to fifteen years were attending a school. The rest of the children were working. Those working as apprentices in the field of trade (such as construction industry) worked sixty-four hours per week in summer and fifty-two hours per week in winter. Some children were employed as servants in rich househoulds. In the middle of the 19th century 120, 000 London children worked as servants eighty hours per week for half a penny per hour (Cody, 2008).

As for the concrete areas, children worked, for instance, in factories, textile factories, shipyards, farms, rich households, coal mines, making hats, cleaning chimneys, scaring birds out of the fields, catching rats, washing, they also worked as street sellers and pickpockets. In those days, steam was a serious energy source. It was mainly used as power drive for ships, trains, but also as energy that drove machinery in factories. In order to produce steam, both water and heat were crucial. The heat was gained by burning large amount of coal which was necessary to extract. Mining companies used children for this work. One of the reason was their short stature which enabled them to maneuver in mines with limited space and accessibility. The second reason was money. These children were paid considerably less than adults. One of the worst conditions children had to work in were coal mines. They had to work in dark which led to serious health issues. The standard ventilation was not available most of the time and coal dust was thick, therefore, it was difficult to breathe normally. Children worked from twelve to eighteen hours per day and their respiratory problems were getting worse. There was a constant noise and plenty of rats. Moreover, children often suffered backed pain since they had to work stooped. Cave-ins and explosions were on a daily basis. There were no safety measures and death was a constant danger (Price 2013).

Griffin (2015) notes that boys in towns were usually employed as chimney sweepers. The age of children starting work differed, most of the time they were around eleven years old. On the other hand, in the industrial areas children started to work earlier. In general, children were forced to work in dangerous and dirty environment for low pay.

Life of children working as chimney sweeps was arduous. Some of the children were only three years old. Their physique enabled them to get inside the narrow chimneys. This work was one of the most onerous for children. Their first climb down the chimney was painful with scrapes and scratches on their elbows and legs. Despite all this, they were mercilessly sent back to work after having their wounds washed in salt water by the master. Later on, children had many calluses which made this work a bit more bearable. The greatest danger at work was falling from roof or getting stuck in a chimney. Constant inhalation of soot caused children lung damage. Many cases of being trapped in a chimney followed by death were recorded in those days. Generally, orphans were used as chimney sweepers and after they grew up they were thrown into the streets. Even more, some children were kidnapped to work as chimney sweepers. Employers often let children starve in order to be thin enough to clean the narrowest chimneys. Children from nine to ten were “too big” to do the work. Unfortunately, children were used for this work even though the chimneys could have been cleaned safer by using a chimney cleaning brush (Price, 2013).

As mentioned earlier, children started to work from very young age. According to Cody (1988), boys and girls started to work in coal mines from the age of five. They died very young, often before they turned twenty-five. In 1833, it was proposed that children from eleven to eighteen could work for maximum twelve hours per day. Children from nine to eleven could work for eight hours per day and children younger than nine years could not work at all. However, these laws concerned only textile factories where children often started working when they were five years old.

However, birth, death and marriage registration established in 1836 enabled to control the age of children accepted to work in factories. The first report of commissioners for children labour in coal mines was published in 1842 written by Lord Ashley (later Shaftesbury, Price, 2013).

In addition, Griffin (2015) mentions that in 1833 the Factory Act came into effect. Since then it was prohibited to employ children younger than nine years. Moreover, the act restrained employers from continuous employment of the youngest.

The Chimney Sweepers and Chimneys Regulation Act adopted in 1840 forbade anyone younger than twenty-one years from climbing on a chimney or getting inside of it for the purpose of cleansing. Mines Act which came into effect in 1842 forbade all girls and women and boys younger than ten years to work in mines. No one younger than fifteen years could operate machines. The Ten Hour Act adopted in 1847 set the working time to ten hours per day and fifty-eight hours per week for women and people younger than eighteen. Another law came into effect in 1875 when a twelve-years boy George Brewster died after his master made him climb on the chimney of Fulbourn Hospital in order to clean it. Lord Shaftesbury who was indignant about this accident initiated a new act which required every chimney sweeper to be registrated at the police station. This Chimney Sweepers Act came into effect in 1875 (Price, 2013). Later on, The Factory Act of 1878 restrained children from working before the age of ten. In addition, this act applied to all kinds of trades. It was followed by the second Education Act mentioned in the previous section (Griffin, 2015). Such conditions had a great impact upon the problem of child labour.

Another step was taken towards the issue of child labour in New York, 1881, when a Liverpool businessman Thomas Agnew arranged a meeting with The National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (SPCC). He was so impressed by the society that after he returned to England he started to work on the same project in Liverpool. This society was officially established in 1891. Paradoxically, it came into existence sixty-seven years after The Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. For Victorian Britain and Europe child labour was nothing exceptional. For centuries, children had been used for work. They were expected to support their families. Over time the laws that slightly improved working conditions of children had been adopted (Price, 2013).

Griffin (2015) draws our attention to the fact that though children had been used for work before industrialisation began, the emergence of new factories led to increased demand for cheap labour. As a result, Victorian society had to face and deal with the problem of child labour.

Children often worked in factories since they represented cheap source of human labour. They worked from Monday to Saturday from six in the morning to eight in the evening. They worked for the minimum of what the adults earned. Compared to boys, girls earned less. Some of the tasks children performed likewise or even better than adults. At times, there were more children working in factories than adults. Children’s rights were undermined. In addition, they generally did the secondary work. Many times, they had to clean under the machines still in motion. Precautions were minimal, therefore, health injuries or even death were nothing unusual. If some of them overslept and did not come to work on time, they were beaten or fined (Price, 2013).

Poverty was a problem that had to be dealt with. Victorian society was aware of the severity of poverty and child labour. Therefore, certain steps were taken in order to improve working conditions.

Conclusion

The Victorian era (1837-1901), as part of history of Great Britain, represents the period of significant changes made in various areas, such as culture, education, working conditions, et cetera. Life of children coming from poorer families was marked by child labour. As a consequence, certain steps had to be taken.

Victorian society was fully aware of the importance of education. This awareness was reflected in education acts which came into effect between 1870 and 1891. As a result, a compulsory school attendance was established. The way schools were being established was about to change. Since 1870 local authorities were obliged to establish schools at the financial expense of local taxpayers.

Industrialisation brought not only innovation and progression, but also called for the increased demand for cheap labour. Thus, children were overused, paid less and forced to work in unhealthy environment. However, new laws established in the field of child labour had a great influence upon the improvement of their working conditions and everyday life.

Bibliography

- Booth, W. (1890) In Darkest England and the Way Out. New York, NY: Funk & Wagnalls. Retrieved from https://archive.org/stream/indarkestenglan00bootgoog#page/n8/mode/2up

- Cody, D. (2016). Child Labor. Retrieved from http://www.victorianweb.org/history/hist8.html

- Disraeli, B. (1845). Sybil, or The Two Nations. London, ENG: Henry Colburn. Retrieved from https://archive.org/stream/sybilortwonation01disr#page/n0/mode/2up

- Griffin, E. (2015) Child Labour. Retrieved from https://www.bl.uk/romantics-andvictorians/articles/child labour

- McDowall, D. (1989). An Illustrated history of Britain. Harlow, ESX: Longman group UK Limited

- Morgan, K.O. (2006). The History of Britain and Ireland. Oxford, OFE: Oxford University Press.

- Picard, L. (2015). Education in Victorian England. Retrieved from http://www.bl.uk/victorianbritain/articles/education-in-victorian-britain

- Price, P. (2013). Victorian Child Labor and the Conditions They Worked. Retrieved from http://www.victorianchildren.org/victorian-child-labor/

- Price, P. (n.d.). Victorian Schools Facts for Children. Retrieved from http://www.victorianchildren.org/victorian-houses-how-victorians-lived/

- Robinson, W.C. 2002. Population policy in Early Victorian England. European Journal of Population, vol. 18, no. 2 (ISSN 0168-6577), p. 153-173. Retrieved from http://www.cesruc.org/uploads/soft/130306/1-130306151Q1.pdf

Originally published by Univerzitná Knižnica under an Open Access license.