Puckle’s invention didn’t change warfare in his own era, but it contributed to an ongoing conversation about how societies imagine the relationship between violence and virtue, mechanism and morality.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: A Gun Before Its Time

The year was 1718. In a world teetering between the residual turbulence of the English Civil Wars and the expanding ambitions of global empires, a London inventor named James Puckle introduced something astonishing. It was not a musket, nor quite a cannon, but a contraption that promised to fire multiple rounds rapidly from a rotating chamber. The Puckle Gun, as it came to be known, was perhaps the first true attempt at a rapid-fire firearm designed for land or sea defense. Yet, despite its conceptual novelty, it failed to revolutionize warfare in its own age.

This failure was not technological alone. The Puckle Gun’s story is embedded in the entanglement of Enlightenment ingenuity, commercial interest, and martial pragmatism. It illustrates the perennial gap between invention and adoption, between what a society can build and what it will use. Though often cited as a proto-machine gun, the Puckle Gun was not merely a curiosity or footnote in the history of arms. It was a mirror reflecting the tensions of its time, between old and new, handcraft and mechanism, warfare and moralized violence.

Mechanism and Ambition: The Design of the Puckle Gun

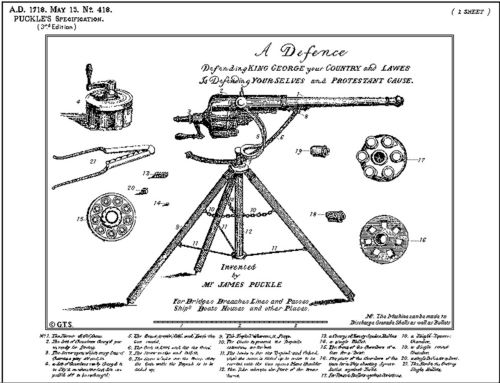

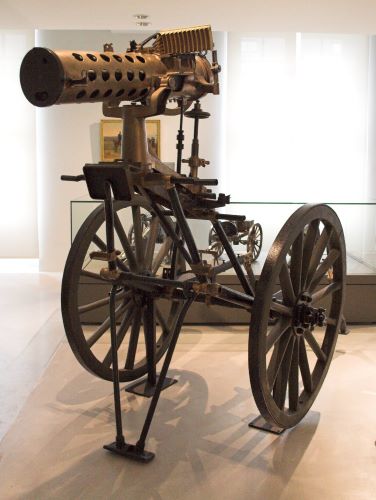

At its core, the Puckle Gun was a flintlock firearm mounted on a tripod, with a manually operated crank that rotated a cylinder containing multiple preloaded chambers.1 Its most basic function was straightforward: deliver rapid, consecutive shots without the need to reload after each one. The gun was intended primarily for naval defense, particularly to repel boarding parties.

The Puckle Gun’s mechanical ambition placed it at the crossroads of pre-industrial craftsmanship and the dreams of automation. It incorporated a cylinder-and-crank design that prefigured later revolver mechanisms, though it lacked the efficiency and reliability of 19th-century metallurgy. Reloading was still slow, requiring the operator to replace the entire cylinder, which meant its “machine gun” classification remains more conceptual than practical.

Still, the very act of inventing such a weapon was a statement of intent. Puckle imagined a world in which fewer men could defend more territory with less effort. His patent claimed the gun would be “useful in defending ships, and other places” and “discharging round bullets” against Christians and “square bullets” against “the Turks and infidels”.2 The gun was, quite literally, cast in moral and theological terms, a tool of salvation as much as slaughter.

Context of Invention: Enlightenment Violence

To understand the Puckle Gun, one must grasp the cultural and political moment that gave rise to it. The early 18th century was a time of ideological ferment and imperial expansion. England was emerging as a naval power with growing commercial interests abroad, from the Caribbean to India. The need for portable, efficient defenses was as practical as it was symbolic. Defending a ship was not merely an act of self-preservation but an assertion of mercantile sovereignty.

At the same time, this was the age of Locke, Newton, and the Royal Society. Puckle himself was embedded in the milieu of London’s inventors and speculative financiers, who saw no contradiction between mechanistic science and imperial conquest.3 The Puckle Gun stands as a revealing artifact of this mindset: rational, mathematical, and yet deeply embedded in the theological and political anxieties of its day.

It was marketed as a “Defence Gun” to investors, not a weapon of aggression. This naming was no accident. In an era when standing armies were still politically suspect in Britain and militias were valorized, a defensive weapon promised moral clarity. Its purpose was to hold borders rather than expand them, to repel rather than to conquer. Yet in practice, the very idea of defense, especially on the high seas, was inseparable from the projection of imperial power.

Commercialization and Failure: A Gun That Didn’t Sell

Despite its mechanical ingenuity and moral marketing, the Puckle Gun did not succeed commercially. It saw few, if any, active deployments. Most records suggest only two were ever built and tested, with trials demonstrating moderate success but highlighting problems with reliability, heat, and cylinder swapping speed.4

The failure was not entirely the gun’s fault. The British Board of Ordnance, skeptical of unproven technologies, declined to commission it. Manufacturing such complex devices remained expensive, slow, and inconsistent in the pre-industrial era. Without mass production or standardized parts, each unit required time-consuming craftsmanship.

In addition, military commanders and naval officers were hesitant to adopt a device that required both mechanical skill and trust in an unorthodox form. Inertia favored the musket and swivel gun. And while inventors like Puckle dreamed of battlefield transformation, those in power remained tethered to what was known, proven, and simple to maintain under fire.

Moreover, the weapon’s very innovation worked against it. Military culture, then as now, is often conservative in its adoption of new tools. The prospect of a rotating gun, unfamiliar to its users and potentially dangerous if mismanaged, presented more risk than reward in the heat of battle. In the Puckle Gun, commanders saw potential but also unpredictability.

Symbol and Myth: The Puckle Gun in Retrospect

What makes the Puckle Gun fascinating is not its technical success but its symbolic afterlife. In many ways, it has become a mythic precursor to the Gatling gun and other nineteenth-century rapid-fire weapons. Modern narratives often cast it as a failed genius project, a lone visionary’s glimpse into a mechanized future.5 This retrospective romanticism obscures the deeply contextual nature of the gun’s development.

James Puckle was not a marginal figure scribbling blueprints in isolation. He was a writer, a notary, and a man of letters with ties to political and financial circles. His invention must be read alongside his 1711 book The Club, which offered Christian moral dialogues framed against the perils of foreign influence.6 The Puckle Gun was, in many ways, the mechanical expression of that text, a technological embodiment of moral vigilance.

The very notion that a gun might shoot “round bullets” at Christians and “square bullets” at Muslims is not just a technical aside; it is a window into the cultural logic of early modern violence. These bullets were never produced en masse, but the distinction reveals a world where form and function were imbued with moral geometry. The Puckle Gun was not simply an instrument of war. It was an ethical machine, designed to kill with precision and with purpose.

Conclusion: A Cautionary Tale of Invention and Ideology

The Puckle Gun reminds us that technological innovation is not a neutral or inevitable process. It arises within ideological frameworks, and its success or failure depends not merely on functionality but on timing, context, and perception. Puckle’s invention may not have changed warfare in his own era, but it contributed to an ongoing conversation about how societies imagine the relationship between violence and virtue, mechanism and morality.

In this light, the Puckle Gun was not ahead of its time. It was entirely of its time. Its failure does not make it irrelevant. On the contrary, its very existence exposes the hesitations of early modern societies confronting the edge of industrial transformation. It forces us to consider what kinds of violence a culture is willing to automate, and under what justifications.

Far from a forgotten footnote, the Puckle Gun belongs at the center of a deeper inquiry: not into how weapons work, but into what they mean.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Howard Ricketts, Firearms (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1962), 77.

- James Puckle, Patent No. 418 (London: Board of Trade Patent Office, 1718).

- Roy Porter, The Creation of the Modern World: The Untold Story of the British Enlightenment (New York: Norton, 2001), 219.

- Harold L. Peterson, Arms and Armor in Colonial America, 1526–1783 (New York: Bramhall House, 2000), 132.

- DK, Firearms: The Illustrated History (New York: DK Publishing, 2014), 89.

- James Puckle, The Club; or, A Dialogue Between Father and Son (London: J. Roberts, 1711).

Bibliography

- DK. Firearms: The Illustrated History. New York: DK Publishing, 2014.

- Puckle, James. Patent No. 418. London: Board of Trade Patent Office, 1718.

- ———. The Club; or, A Dialogue Between Father and Son. London: J. Roberts, 1711.

- Peterson, Harold L. Arms and Armor in Colonial America, 1526–1783. New York: Bramhall House, 2000.

- Porter, Roy. The Creation of the Modern World: The Untold Story of the British Enlightenment. New York: Norton, 2001.

- Ricketts, Howard. Firearms. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1962.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.29.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.