The postwar monetary system rested not simply on American economic magnitude, but on negotiated rules, shared expectations, and allied consent.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Bretton Woods and the Architecture of Postwar Stability

The Bretton Woods system emerged from the wreckage of interwar economic fragmentation and the geopolitical devastation of the Second World War. Designed in 1944 at the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference in New Hampshire, it sought to prevent a recurrence of the competitive devaluations, tariff escalation, and financial instability that had characterized the 1930s. Policymakers recognized that economic disorder had amplified political nationalism and conflict. The new architecture aimed to embed monetary stability within institutional cooperation. At its center stood the United States, whose industrial capacity, gold reserves, and creditor position gave it unparalleled leverage in shaping the postwar order.

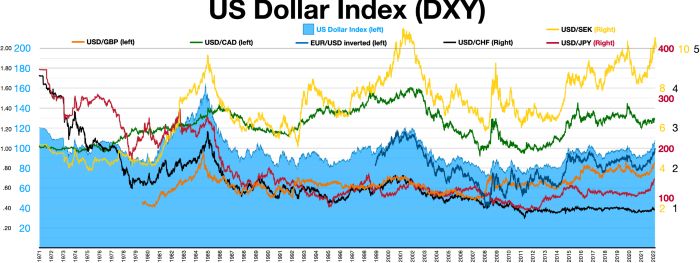

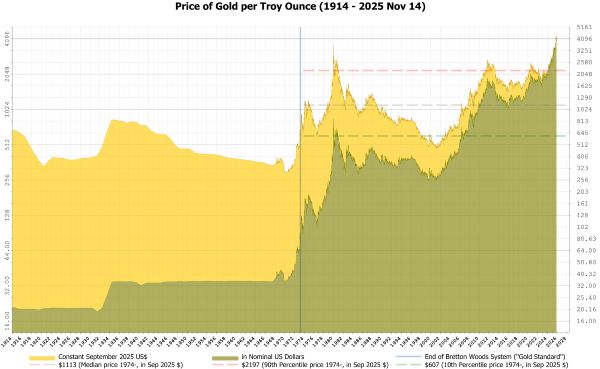

The system rested on a hybrid structure. Currencies were pegged to the U.S. dollar at fixed but adjustable exchange rates, while the dollar itself was convertible into gold at $35 per ounce. This arrangement positioned the dollar as the linchpin of global finance. Nations held dollar reserves to stabilize their own currencies, while the United States committed to maintaining gold convertibility for foreign monetary authorities. Stability depended on confidence in American fiscal discipline and gold backing. The architecture institutionalized interdependence by anchoring global liquidity to a single national currency.

Two new institutions reinforced this structure. The International Monetary Fund provided short-term balance-of-payments support and oversight of exchange rate adjustments. The World Bank financed reconstruction and development, particularly in war-torn Europe and later in the developing world. Together, these bodies aimed to prevent the disorderly monetary nationalism that had undermined the interwar system. Bretton Woods did not eliminate national sovereignty, but it embedded it within cooperative constraints designed to sustain open trade and predictable exchange relationships.

The durability of the system during the 1950s and early 1960s reflected both American dominance and allied consent. The United States supplied global liquidity through trade deficits and overseas investment, while European and Japanese recovery increased demand for stable exchange relations. Dollar centrality was not merely imposed; it was accepted as functional. The architecture of postwar stability rested on a combination of material capacity and institutional legitimacy. Centrality operated through structured cooperation rather than coercive leverage, creating an order that was stable so long as confidence in American stewardship endured.

Structural Strain: Dollar Overhang and the Triffin Dilemma

By the late 1950s and throughout the 1960s, the very success of the Bretton Woods system began to generate internal contradictions that its architects had not fully anticipated. As global trade expanded and European and Japanese economies recovered from wartime devastation, the demand for dollar reserves increased substantially. The dollar had become the principal medium through which international settlements were conducted, and foreign central banks accumulated it as a stabilizing asset. The United States supplied these reserves by running persistent balance-of-payments deficits, allowing dollars to circulate abroad as the lubricant of the international system. American military spending, overseas investment, and foreign aid programs further expanded the global dollar supply. What had initially been a stabilizing mechanism gradually produced tension. Foreign central banks held growing quantities of dollars, yet U.S. gold reserves remained finite and did not expand proportionally. The structural gap between outstanding dollar liabilities and available gold backing widened year by year, raising questions about the long-term credibility of the fixed $35 per ounce conversion commitment.

This imbalance crystallized in what economist Robert Triffin famously described as a structural dilemma inherent in reserve currency systems. For the dollar to function as the world’s reserve currency, the United States had to provide sufficient liquidity to sustain expanding global commerce, which required ongoing deficits and outward capital flows. Yet sustained deficits eroded confidence in the dollar’s convertibility into gold, undermining the credibility that anchored the system. If the United States eliminated deficits to protect gold reserves, global liquidity would contract, threatening deflation and recession in trading partners dependent on dollar reserves. If it continued running deficits, foreign governments might increasingly doubt the United States’ capacity to honor gold convertibility and demand bullion redemption. The paradox was stark: the system required the United States to weaken its gold position in order to sustain global growth, but weakening that position threatened the system itself. The Triffin dilemma revealed that Bretton Woods rested on confidence in American stewardship rather than on mechanical balance.

By the mid-1960s, pressure intensified. Rising U.S. expenditures on the Vietnam War and domestic social programs expanded fiscal deficits. Inflationary pressures grew. European governments, particularly France under President Charles de Gaulle, openly criticized dollar privilege and questioned the sustainability of American monetary leadership. Gold outflows accelerated as foreign central banks converted dollars into bullion. Confidence eroded not through sudden collapse but through incremental doubt. The architecture of stability began to reveal structural strain.

These developments did not immediately dismantle Bretton Woods, but they narrowed the margin for maneuver. The accumulation of dollar liabilities abroad, often referred to as the “dollar overhang,” meant that outstanding claims on U.S. gold far exceeded available reserves. The system depended increasingly on confidence rather than convertibility. As strain mounted, the question was no longer whether reform would occur, but how and under what conditions. The tension between global liquidity provision and domestic stability became the central fault line of the postwar monetary order.

August 15, 1971: The Nixon Shock

On August 15, 1971, President Richard Nixon announced a series of measures that fundamentally altered the structure of the international monetary system and marked a decisive break with the postwar economic order. In a nationally televised address, Nixon declared the temporary suspension of the dollar’s convertibility into gold for foreign monetary authorities, effectively closing the so-called “gold window.” This decision ended the central pillar of Bretton Woods, which had anchored global exchange rates to the dollar and the dollar to gold at $35 per ounce. Although framed as a defensive response to speculative attacks and currency imbalances, the move constituted a unilateral restructuring of the system that had governed international finance since 1944. The gold commitment had symbolized American monetary credibility and stewardship. Its suspension, undertaken without prior consultation with allied governments, signaled that the United States was prepared to redefine the rules of global monetary exchange on its own terms.

The announcement formed part of a broader domestic and international policy package designed to stabilize the American economy and recalibrate trade relations. Nixon imposed wage and price controls in an effort to combat inflationary pressures that had intensified during the late 1960s. Simultaneously, he introduced a temporary 10 percent surcharge on imports, explicitly aimed at pressuring trading partners to revalue their currencies and negotiate more favorable terms for the United States. The surcharge functioned as leverage, linking monetary reform to trade concessions. In his address, Nixon presented these actions as necessary to defend American workers, curb inflation, and ensure fairness in international commerce. The rhetoric emphasized sovereignty, national strength, and decisive leadership. Yet the abruptness of the measures underscored a departure from the consultative processes that had characterized postwar monetary cooperation. Allies were not brought into prior deliberation; they were confronted with a completed decision.

International reaction was immediate and unsettled. European governments expressed frustration at the lack of consultation and concern over the implications for exchange rate stability. Japan, whose export-driven economy depended heavily on access to the American market, faced significant currency pressure. Central banks scrambled to manage exchange markets as speculative flows intensified. The suspension of convertibility disrupted expectations that had governed international settlements for nearly three decades. The shock was not merely economic; it was diplomatic.

In the months that followed, negotiations produced the Smithsonian Agreement of December 1971, which attempted to realign exchange rates and preserve a modified version of the fixed-rate system. Currencies were revalued, and the dollar was officially devalued against gold. Yet these adjustments did not resolve the underlying structural tension. Speculative pressures continued, and confidence in fixed parities eroded further. By 1973, major currencies shifted to generalized floating exchange rates, marking the effective end of Bretton Woods as originally conceived.

The Nixon Shock did not signal American withdrawal from global leadership or immediate collapse of dollar dominance. The United States remained the world’s largest economy, and the dollar continued to serve as the principal reserve currency. American financial markets retained unmatched depth, liquidity, and institutional credibility. Yet the character of centrality changed in subtle but significant ways. The dollar’s dominance was no longer anchored to a gold commitment but to confidence in U.S. economic management and geopolitical power. Convertibility had provided a tangible guarantee; its removal shifted the system toward reliance on trust and market perception. The transition from fixed to floating rates represented not chaos but transformation. Monetary centrality survived, but the institutional architecture that had supported it was permanently altered.

The significance of August 15 lies not only in the technical decision to suspend gold convertibility but in the precedent it established. A dominant economic power had unilaterally redefined the rules of the system upon which its allies depended. The move demonstrated that centrality could be leveraged decisively and without prior coordination. While the United States did not lose its position overnight, the shock encouraged partners to reconsider their exposure to American policy decisions. The architecture of postwar stability had been rewired by executive action.

Immediate Reaction: Europe and Japan Confront Monetary Disruption

The immediate response to the Nixon Shock in Europe and Japan was characterized by a mixture of alarm, frustration, and strategic recalibration. For nearly three decades, these economies had structured monetary policy around the stability of the Bretton Woods framework. The abrupt suspension of gold convertibility and the imposition of an import surcharge introduced uncertainty into exchange markets and trade relations. European leaders viewed the unilateral decision as a breach of the cooperative norms that had underpinned postwar reconstruction. The diplomatic strain was as significant as the monetary disruption, as allied governments confronted the reality that the United States had acted without prior consultation.

Financial markets reacted swiftly. Currency speculation intensified as traders anticipated revaluations and potential breakdown of fixed exchange rate commitments. Several European governments temporarily closed foreign exchange markets to stem volatility. Japan, whose economy depended heavily on export competitiveness, faced intense upward pressure on the yen. Policymakers in Tokyo were forced to intervene in currency markets and consider structural adjustments to maintain stability. The disruption extended beyond exchange rates; it challenged the credibility of long-standing monetary commitments.

In December 1971, negotiations among major industrialized nations produced the Smithsonian Agreement, an attempt to restore order through coordinated realignment. The agreement devalued the dollar and widened permissible exchange rate bands, offering temporary relief. Yet the arrangement exposed the fragility of the system. The new parities required sustained cooperation and confidence that speculative pressures would subside. For European and Japanese policymakers, the experience underscored their vulnerability to American policy decisions. The structural imbalance that had produced the Nixon Shock was not resolved; it had merely been reconfigured.

By 1973, the fixed exchange rate regime unraveled entirely. Repeated currency crises and speculative attacks rendered the Smithsonian framework unsustainable. Major economies shifted toward floating exchange rates, marking the effective end of the Bretton Woods system. For Europe and Japan, this transition required recalibrating monetary policy around market-determined exchange values rather than fixed parities. The move to floating did not eliminate coordination, but it reduced dependence on a single anchor currency in the formal sense.

The longer-term reaction in Europe extended beyond immediate stabilization. European policymakers accelerated discussions about deeper monetary cooperation as a means of reducing exposure to unilateral American action. Early efforts such as the “snake in the tunnel” sought to limit exchange rate fluctuations among European Community members. Although these mechanisms faced their own challenges, they represented a deliberate attempt to institutionalize regional stability independent of direct dollar anchoring. Japan, while remaining closely tied to the American market, also adjusted its policy framework to accommodate greater currency flexibility. The Nixon Shock catalyzed not only short-term disruption but strategic reflection among allies about how to manage monetary interdependence in a system no longer anchored to gold.

From Shock to System: The Collapse of Bretton Woods

The Nixon Shock did not immediately dismantle the Bretton Woods system, but it removed its central guarantee and exposed the fragility beneath its formal structure. The Smithsonian Agreement attempted to restore fixed exchange rates through negotiated realignment, yet the underlying tension between dollar liquidity and confidence in its value remained unresolved. The widening of exchange rate bands provided temporary flexibility, but speculative capital flows continued to test the credibility of official parities. Confidence, once shaken, proved difficult to rebuild.

By 1972 and early 1973, currency markets again experienced instability as inflationary pressures and divergent national economic conditions strained coordinated commitments. The United States continued to face domestic inflation linked to fiscal expansion and loose monetary conditions, while European and Japanese economies pursued their own stabilization strategies. These policy divergences complicated efforts to maintain fixed exchange rate alignments. Several European currencies came under repeated speculative attack, forcing governments to intervene heavily in foreign exchange markets. Defending parities required the use of reserves and often sharp adjustments in interest rates, which carried domestic economic costs. The dollar, though formally devalued, remained the focal point of uncertainty. The structural coherence of Bretton Woods had depended on synchronized discipline among major economies. Once gold convertibility ended, that shared anchor dissolved, leaving coordination dependent on political will rather than institutional constraint.

In March 1973, major industrialized countries effectively abandoned fixed exchange rates and moved toward generalized floating. The shift was less a dramatic proclamation than an accumulation of practical decisions acknowledging that the previous framework could no longer be sustained. Floating rates allowed currencies to adjust according to market supply and demand rather than through negotiated parities. While some economists had advocated greater flexibility as a means of absorbing shocks, the transition represented a profound institutional break from the architecture designed in 1944. The rules governing exchange stability were no longer codified in gold convertibility or narrow bands, but in the management of volatility within increasingly integrated financial markets.

The collapse of Bretton Woods illustrates how unilateral action can catalyze systemic transformation without immediate disorder or geopolitical rupture. The dollar remained central in global finance, and U.S. capital markets continued to provide unmatched depth and liquidity. Yet its role was redefined in subtle but enduring ways. Convertibility had offered a tangible guarantee linking currency value to a physical reserve; floating substituted market confidence, institutional credibility, and geopolitical strength for metallic backing. The international monetary system evolved into a more decentralized, capital-mobile regime in which exchange rate volatility became a structural feature rather than an aberration. What began as an executive decision framed as temporary protection became the foundation of a new monetary order. The shock became a system through cumulative adaptation rather than dramatic collapse.

European Monetary Coordination and the Long Road to the Euro

The end of Bretton Woods did not eliminate Europe’s dependence on the dollar overnight, but it intensified the perceived vulnerability of European economies to American monetary decisions. The Nixon Shock revealed that the United States could unilaterally redefine the rules governing international finance, even when those rules structured allied recovery and integration. European policymakers drew a structural lesson: stability could not rely exclusively on external anchoring. If exchange rate predictability and monetary discipline were to endure, they would need to be institutionalized regionally.

The first effort to construct such insulation emerged in 1972 with the so-called “snake in the tunnel.” The arrangement aimed to limit exchange rate fluctuations among European Community currencies within a narrow band while collectively floating against the dollar. By constraining intra-European currency volatility, policymakers sought to preserve the integrity of the common market and prevent competitive devaluations among member states. The “tunnel” referred to the wider fluctuation margins against the dollar permitted under the Smithsonian Agreement, while the “snake” described the tighter European band within it. Although fragile and frequently tested by divergent inflation rates, fiscal imbalances, and the oil shocks of the 1970s, the mechanism reflected a clear strategic objective. European governments recognized that monetary fragmentation could undermine broader integration efforts. The initiative signaled a decisive shift from reliance on American anchoring toward regional coordination as a structural hedge.

The instability of the 1970s, including inflationary pressures and oil crises, exposed the limits of partial coordination. Several currencies withdrew from the snake, and exchange rate realignments proved frequent. Yet the experience reinforced rather than eliminated the commitment to deeper monetary integration. Policymakers concluded that more structured mechanisms were necessary to sustain stability. The failure of informal coordination encouraged institutionalization.

In 1979, the European Monetary System (EMS) formalized this ambition. Anchored by the Exchange Rate Mechanism and supported by the European Currency Unit as a unit of account, the EMS sought to stabilize currency relationships among participating states through coordinated intervention and policy convergence. The system introduced clearer rules for exchange rate adjustments and created expectations of sustained cooperation. While not immune to speculative attacks or macroeconomic divergence, the EMS represented a qualitative shift toward institutionalized monetary governance. It embedded exchange rate discipline within a framework that encouraged convergence in inflation and fiscal policy. Monetary coordination became intertwined with broader political integration, reinforcing the idea that economic sovereignty could be pooled to enhance collective resilience.

The long arc of this process culminated decades later in the creation of the euro. The Maastricht Treaty of 1992 codified convergence criteria on inflation, deficits, debt levels, and exchange rate stability, laying the groundwork for monetary union. These criteria were not merely technical thresholds but political commitments to shared discipline. By 1999, the euro was introduced as a common currency for participating states, initially in electronic form, with physical notes and coins circulating in 2002. The European Central Bank assumed responsibility for monetary policy across the eurozone, further institutionalizing integration. The euro did not eliminate Europe’s engagement with the dollar or global markets, but it created a regional monetary pole capable of operating independently. What began as defensive coordination evolved into a durable alternative framework within the international system.

The trajectory from the Nixon Shock to the euro illustrates how unilateral action by a dominant power can accelerate institutional hedging among allies. Europe did not seek immediate rupture with the United States, nor did it abandon transatlantic economic ties. Instead, it pursued layered coordination mechanisms that gradually reduced vulnerability to external monetary shifts. Centrality remained American, but European integration introduced structural diversification within the global system. The lesson is not displacement but recalibration. When confidence in a single anchor weakens, partners respond by embedding cooperation within their own institutional architecture, creating resilience without outright confrontation.

Structural Lesson: Centrality Weaponized Encourages Institutional Hedging

The Nixon Shock reveals a structural principle that extends beyond the technical details of gold convertibility and exchange rate regimes. When a dominant economic power leverages its central position abruptly, particularly without consultation, it alters the incentive structure for its partners in durable ways. Centrality confers influence because others depend on access to the dominant actor’s currency, market, or institutional architecture. Yet that same dependency creates latent vulnerability. If the dominant power demonstrates that it can redefine rules unilaterally, interdependent states must reassess their exposure. The immediate objective of unilateral action may be domestic stabilization, bargaining leverage, or political signaling. The systemic consequence, however, is often the institutionalization of alternatives designed to reduce risk. What appears as decisive assertion of sovereignty can function, at the structural level, as a catalyst for diversification.

Weaponized centrality differs fundamentally from cooperative leadership. Under Bretton Woods, dollar dominance was embedded within negotiated rules and sustained by allied consent. American monetary power operated within an institutional framework that reassured partners about predictability and shared benefit. The suspension of convertibility shifted that perception from steward to unilateral actor. Even when the policy was framed as temporary and defensive, the precedent reshaped expectations. Allies recalibrated assumptions about reliability and consultation. Institutional hedging did not require ideological rupture or anti-American alignment. It required prudence in the face of demonstrated vulnerability. European monetary coordination emerged not as rebellion but as strategic insurance. The lesson absorbed by policymakers was subtle but enduring: reliance on a single external anchor carries risk when that anchor can redefine commitments without negotiation.

Institutional hedging operates gradually. It rarely manifests as dramatic rupture. Instead, states build mechanisms that reduce sensitivity to unilateral decisions by a central power. These mechanisms may include regional agreements, shared regulatory frameworks, alternative settlement systems, or coordinated intervention policies. Such structures accumulate. They do not necessarily displace the dominant actor immediately. Rather, they redistribute structural leverage. Centrality becomes less absolute and more conditional.

The broader lesson is that dominance, when exercised without consultation, invites structural diversification. A system anchored to a single node can endure as long as that node is perceived as stable and predictable. When predictability weakens, partners respond by embedding resilience within their own institutions. The dominant power may retain economic magnitude, but its uncontested centrality erodes incrementally. Institutional hedging represents adaptation rather than confrontation. It is the rational response of interdependent actors in a system where leverage has been demonstrated as unilateral.

Contemporary Echoes: Unilateral Economic Policy in the 21st Century

In the twenty-first century, the structural dynamics visible in 1971 reappear in altered form. The United States continues to occupy a central position in global finance through the dominance of the dollar, the depth of its capital markets, and the scale of its consumer economy. Yet centrality today extends beyond monetary anchoring to encompass trade policy, financial sanctions, and regulatory reach. When unilateral economic measures are deployed, whether through tariffs, export controls, or sanctions regimes, they reverberate across interconnected supply chains and financial networks. The logic of leverage remains powerful. So too does the incentive for hedging.

Under President Donald Trump, tariff escalation and the framing of trade relationships as competitive contests have reintroduced unilateral economic pressure into the center of American policy. Tariffs on strategic sectors and broad categories of imports are presented as instruments of correction and national defense. The assumption underlying these measures is that the United States’ economic gravity compels accommodation. Yet partners increasingly respond by diversifying exposure. Regional trade agreements advance without American participation. Currency swap arrangements and alternative settlement mechanisms expand. Supply chains adjust incrementally to reduce vulnerability to sudden policy shifts.

The use of financial sanctions and export controls further illustrates the dual nature of centrality in the contemporary system. Dollar dominance allows the United States to restrict access to global financial networks, including the ability to deny institutions entry into dollar clearing systems or to impose compliance requirements with extraterritorial reach. In the short term, these tools can be highly effective in exerting pressure and signaling resolve. Yet their repeated deployment also communicates the strategic risks associated with dependence on American-controlled financial infrastructure. States that may otherwise accept dollar centrality begin exploring alternative payment channels, regional clearing arrangements, and increased use of local currencies in bilateral trade. Initiatives aimed at reducing exposure to U.S. financial jurisdiction do not necessarily reflect ideological opposition; they reflect risk management. As these mechanisms are tested and refined, they become institutionalized. The cumulative effect is diversification rather than immediate displacement. The pattern echoes earlier historical moments in which the exercise of leverage accelerated structural adaptation among those subject to it.

The contemporary lesson aligns with the historical record. Unilateral economic policy does not necessarily collapse existing hierarchies, nor does it automatically isolate the initiating power. Instead, it reshapes incentives. Allies and competitors alike invest in institutional resilience to buffer against unpredictability. Centrality persists, but it becomes contested and conditional. In a highly interconnected global economy, dominance exercised without consultation encourages gradual realignment. The architecture of dependence evolves, not through dramatic rupture, but through accumulated diversification.

Contemporary Repetition: Trump and the Incentive to Build around the United States

The reassertion of tariff politics and economic threat framing from Trump reflects a renewed confidence in American indispensability. The premise is straightforward: the United States remains the world’s largest consumer market, the issuer of the dominant reserve currency, and a central node in global supply chains. From this vantage point, leverage appears durable. Tariffs, trade investigations, and public pressure campaigns are presented as tools capable of extracting concessions because access to the American market is presumed irreplaceable. Yet structural centrality, as history suggests, is rarely static.

The repeated use of tariffs against both competitors and allies alters the calculus of interdependence in subtle but cumulative ways. Even when measures are framed as temporary, strategic, or corrective, they introduce volatility into long-term economic planning. Firms that rely on predictable cost structures must factor in the possibility of sudden duties or retaliatory measures. Governments that once assumed relative stability in trade relations reassess their exposure to abrupt executive action. As a result, alternative trade agreements that exclude the United States gain institutional momentum, not necessarily as acts of opposition but as mechanisms of risk management. Regional frameworks in Asia and Europe proceed with deeper integration among participating states, often without expecting American reentry. Supply chains diversify geographically, and procurement strategies are recalibrated to reduce concentration risk. The incentive driving these adjustments is predictability. When access to a central market becomes politically contingent, diversification becomes rational.

Financial policy amplifies this dynamic in ways that extend beyond tariffs. Dollar dominance continues to anchor global liquidity, and U.S. capital markets remain unparalleled in depth and resilience. Yet the demonstration that access to dollar clearing systems, financial institutions, or sanctioned markets can be restricted under executive authority encourages incremental diversification efforts. States explore expanded currency swap lines to buffer against liquidity shocks. Bilateral trade agreements increasingly incorporate provisions for settlement in local currencies to reduce transaction exposure. Investment in alternative payment infrastructures receives renewed attention, particularly among major economies seeking greater insulation from external leverage. None of these developments displace the dollar in the near term. They do, however, represent strategic hedging behavior. As mechanisms are tested and normalized, they become part of the structural landscape, gradually reducing the degree to which global finance depends exclusively on a single node.

The pattern parallels earlier episodes in which centrality was asserted abruptly. Allies do not sever ties overnight. They construct layered alternatives. Economic networks, much like maritime trade routes or monetary regimes, reorganize gradually. A dominant power may retain magnitude while losing unquestioned centrality. The critical variable is not size, but predictability. When predictability diminishes, diversification accelerates.

The structural lesson is consistent with the trajectory traced from Bretton Woods to the present. When a dominant economy leverages its position without sustained consultation, partners respond by embedding resilience within their own institutions. President Trump’s current policies illustrate how economic leverage can prompt systemic adaptation. The United States remains central, but centrality exercised as pressure encourages others to reduce exposure. Institutional hedging, once initiated, rarely reverses quickly. It accumulates, reshaping the architecture of interdependence incrementally rather than dramatically.

Conclusion: Dominance Without Consultation and the Architecture of Alternatives

The arc from Bretton Woods to the present demonstrates that dominance alone does not guarantee permanence. The postwar monetary system rested not simply on American economic magnitude, but on negotiated rules, shared expectations, and allied consent that embedded dollar centrality within a cooperative institutional framework. For nearly three decades, that architecture provided stability precisely because it combined asymmetry of power with predictability of process. When President Richard Nixon suspended gold convertibility in 1971, the United States did not forfeit its central role in global finance. It retained the world’s largest economy and the deepest capital markets. Yet it redefined the terms of centrality unilaterally. That redefinition altered incentives across the system. Europe’s gradual move toward monetary coordination and, ultimately, the euro illustrates how unilateral assertion can catalyze institutional adaptation among partners who remain interdependent but no longer wish to remain exclusively exposed.

Centrality functions most effectively when it is perceived as stable, rule-bound, and predictable. Economic dominance creates influence, but influence sustained through consultation reinforces legitimacy. When dominance is exercised abruptly or without coordination, even in pursuit of domestic stabilization or strategic leverage, it introduces uncertainty into networks built on long-term expectations. States embedded in those networks respond not emotionally but structurally. They diversify trade relationships, institutionalize regional cooperation, expand currency arrangements, and invest in financial mechanisms that reduce exposure to sudden policy shifts. These responses do not require antagonism toward the dominant power. They reflect prudence in a system where interdependence carries risk. Institutional hedging becomes a rational strategy for managing vulnerability without severing ties.

The contemporary landscape under President Donald Trump reveals a repetition of this dynamic. Tariffs and economic threats deployed from a position of confidence in American indispensability generate short-term leverage. Yet they also signal volatility. As in earlier eras, allies and competitors alike hedge by deepening intra-regional agreements, diversifying settlement mechanisms, and embedding resilience within their own institutions. The United States remains central, but centrality exercised as pressure encourages the gradual construction of alternatives.

History suggests that systems do not unravel in dramatic moments alone. They evolve through accumulated adjustments to incentives. Dominance without consultation does not immediately dismantle leadership. It encourages the architecture of alternatives. Those alternatives reshape the distribution of leverage within the system. The lesson is structural rather than partisan: power exercised unilaterally invites diversification. In an interconnected global economy, predictability sustains centrality. When predictability weakens, institutional hedging becomes the rational path forward.

Bibliography

- Bordo, Michael D., and Barry Eichengreen, eds. A Retrospective on the Bretton Woods System: Lessons for International Monetary Reform. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993.

- Dyson, Kenneth, and Kevin Featherstone. The Road to Maastricht: Negotiating Economic and Monetary Union. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Eichengreen, Barry, “Bretton Woods After 50.” Review of Political Economy 33:4 (2021), 552-569.

- —-. Globalizing Capital: A History of the International Monetary System. 2nd ed. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1996.

- Gavin, Francis J. Gold, Dollars, and Power: The Politics of International Monetary Relations, 1958–1971. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003.

- Helleiner, Eric. States and the Reemergence of Global Finance. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1994.

- —-.The Status Quo Crisis: Global Financial Governance After the 2008 Meltdown. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Irwin, Douglas A. Clashing over Commerce: A History of US Trade Policy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017.

- James, Harold. International Monetary Cooperation Since Bretton Woods. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund, 1996.

- Maes, Ivo. “On the Origins of the Triffin Dilemma.” The European Journal of the History of Economic Thought 20:6 (2013), 1122-1150.

- McNamara, Kathleen R. The Currency of Ideas: Monetary Politics in the European Union. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1998.

- Triffin, Robert. Gold and the Dollar Crisis: The Future of Convertibility. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1960.

- Zoeller, Christopher J. P. and Nina Bandelj. “Crisis as Opportunity: Nixon’s Announcement to Close the Gold Window.” Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World 5 (2019).

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.16.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.