Roman “news” was always more than information—it was power.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The Roman Empire, spanning centuries and continents, required a robust system of information dissemination to sustain its political, military, and social infrastructure. In an age without printing presses, radios, or digital media, the communication of news was nevertheless a crucial component of governance and public life. From elite correspondence and military dispatches to public announcements and imperial propaganda, the Romans developed a multi-tiered, sophisticated set of mechanisms for spreading news. This essay explores the methods, media, and purposes of news communication in ancient Rome, highlighting the interplay between information control, social hierarchy, and administrative necessity.

The Roman Concept of “News”

Ancient Roman ideas of “news” were markedly different from the modern idea of a centralized and impartial dissemination of information. In Rome, news was primarily a social and political instrument, transmitted through various informal and formal channels to serve the interests of elites. The most structured form of Roman news was the acta diurna (daily acts), which began under Julius Caesar around 59 BCE. These were daily public notices posted in the Forum, chronicling events ranging from legal proceedings and public decrees to gladiatorial games and births and deaths among the elite. Though intended to be a public record, the acta also served as a vehicle for state propaganda, as the state controlled what was included and how it was presented. These postings represented a Roman understanding of news as inherently tied to state authority and civic identity, not merely a mechanism for sharing facts.1 Read more about this in the next section.

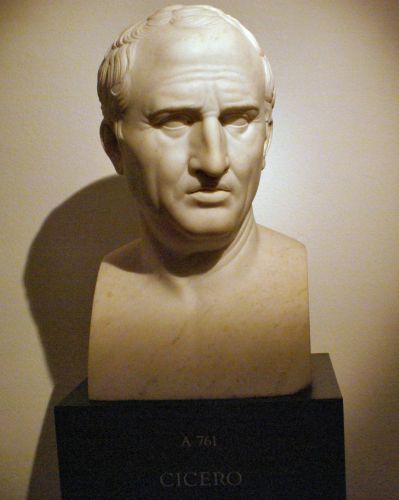

Personal networks also played a critical role in the transmission of news throughout the Roman Republic and Empire. In the absence of a professional journalistic class, senators, governors, and equestrians relied on letters, envoys, and messengers to relay critical information. Cicero’s extensive correspondence provides insight into how news circulated among the elite; he often received political updates from allies stationed in other parts of the empire and sent his own observations in return. These letters served both as personal communication and political intelligence, shaped by the interests and biases of the sender. News was not a neutral good but a curated narrative, tailored to inform allies and persuade others. The reliance on letters and messengers also meant that information was often delayed or distorted, and rumors played a central role in shaping perceptions before official news arrived.2

The concept of nuntius (messenger) and rumor in Roman culture was steeped in political connotation. Romans recognized the strategic use of rumor (fama) as both a threat and a tool, a sentiment echoed in Virgil’s description of Rumor in the Aeneid as a monstrous, winged figure that spreads half-truths with dangerous speed.3 Roman authors, such as Tacitus and Suetonius, frequently noted the power of rumor in the shaping of imperial reputations and the outcome of public opinion. The emperors themselves often manipulated these channels, understanding that controlling perception could legitimize rule or undermine enemies. As such, “news” in Rome included not only factual reports but also carefully disseminated rumors, literary tropes, and official declarations designed to elicit specific reactions from specific audiences.4

Roman news culture was also visually performative. Public spectacles, imperial processions, and military triumphs served as choreographed messages to communicate imperial strength, divine favor, and political legitimacy. These events were not only entertainment but also propaganda, rich with symbolism and tailored to reinforce specific narratives. The construction of monuments and inscriptions, such as Trajan’s Column or the Res Gestae Divi Augusti, served a similar purpose. They acted as enduring forms of “news” that reported the emperor’s deeds to the public, even in the absence of literacy. These visual “texts” were highly curated, often omitting failures and magnifying successes, effectively shaping public memory and current perception simultaneously.5

The Roman concept of news cannot be separated from the broader mechanisms of power and communication in ancient society. News was not an institution or a public service in the modern sense, but a fluid, multifaceted tool embedded in elite networks, state apparatus, and public performance. The fact that the Roman state eventually formalized news dissemination through the acta diurna suggests a growing recognition of its importance in shaping civic life and political order. Yet even this system remained fundamentally partisan, reflecting the interests of those who held power. The Roman experience thus illustrates how news, far from being a neutral carrier of information, has historically functioned as a cultural construct rooted in authority, literacy, and spectacle.6

The ‘Acta Diurna’: Rome’s “Daily Acts”

The Acta Diurna, often translated as “Daily Acts” or “Daily Public Records,” constituted one of the earliest forms of regular, state-controlled public information in Western history. Established under Julius Caesar around 59 BCE, the Acta Diurna served as a rudimentary gazette, posted publicly on whitewashed boards (album) in the Forum for citizens to read. These postings recorded senatorial decrees, legal proceedings, public appointments, trials, and even social announcements like births, deaths, and marriages. The inception of the Acta was part of Caesar’s broader political reforms aimed at increasing transparency—though on his terms—and asserting his authority through a regularized flow of curated information. The Acta’s establishment marks an important moment in the history of state communication, representing a deliberate attempt to formalize and centralize what had previously been conveyed through rumor and elite correspondence.7

Though the Acta Diurna appeared to serve a democratic function by making information publicly accessible, it was deeply embedded in the mechanisms of imperial power and control. The content was carefully curated and subject to censorship, ensuring that the image of the state, and particularly the emperor, remained favorable. News unfavorable to the regime was omitted, and major military victories, decrees, and civic donations were emphasized. In this sense, the Acta functioned less as journalism and more as a tool of imperial propaganda. This selective reporting illustrates the Roman understanding of public knowledge not as an open right but as something to be managed in service of social order and loyalty to the state.8 The very existence of such a medium underscores the central Roman principle that appearances and public perception were vital components of political power.

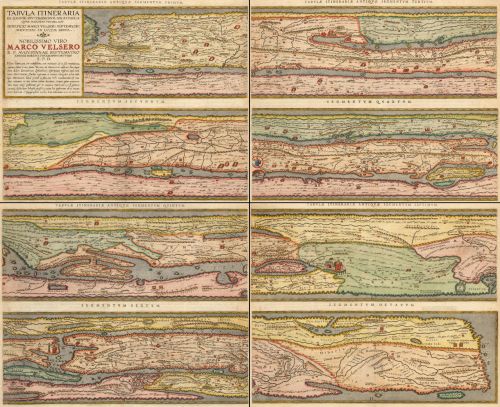

The production and distribution of the Acta Diurna reveal much about the infrastructure of Roman bureaucracy. The scribes who compiled the entries, known as actuarii or diurnarii, gathered reports from various public institutions and officials. Once composed, the daily record was inscribed on the album, read by those in the Forum, and often copied by others to be carried across the empire by merchants, messengers, and provincial administrators. Pliny the Elder mentions that copies of the Acta were sent to provincial governors, demonstrating that even distant officials relied on these documents to remain informed about affairs in Rome.9 In an empire of such vast territorial reach, the Acta Diurna played a central role in creating a shared, if curated, informational reality, binding provincial elites to the rhythms and narratives of Rome.

The reach and influence of the Acta Diurna were not limited to political and legal matters. Social and cultural content was also included, such as reports of gladiatorial games, religious festivals, public works, and significant omens or prodigies. This inclusion reflects the Roman tendency to merge public, religious, and entertainment life within a unified civic framework. These elements served both to inform and to entertain, reinforcing shared Roman values and identities. While literacy was not universal in Rome, the performative nature of the Forum—where literate individuals might read aloud to crowds—ensured that the Acta’s contents reached beyond the literate elite. It thus played an important civic role in shaping public knowledge and behavior, contributing to the cultural cohesion of the Roman populace.10

The Acta Diurna remained a fixture of Roman life well into the imperial period, though it likely declined in importance as centralized imperial administration evolved more complex methods of communication. By the third century CE, references to the Acta become scarce, and it is believed that the practice eventually ceased altogether. Nevertheless, the Acta Diurna stands as a precursor to modern newspapers, embodying the Roman ambition to shape and disseminate information on a daily basis. Its influence is evident not only in its direct administrative function but in its symbolic role as an instrument of authority, discipline, and identity. The Roman use of daily public records reminds us that news—far from being a modern innovation—has long been a site where power, narrative, and public life intersect.11

Private Correspondence and Elite Networks

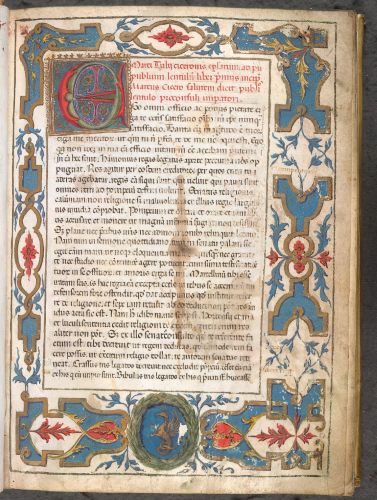

In ancient Rome, private correspondence was a vital mechanism for the transmission of information, the maintenance of political alliances, and the reinforcement of social status. Particularly among the senatorial and equestrian classes, letters were more than casual communications—they were tools of influence and instruments of public life disguised as private exchanges. Roman aristocrats such as Cicero, Pliny the Younger, and Seneca maintained expansive networks through letter writing, often dictating messages to secretaries (amanuenses) who would then dispatch them via messengers. These correspondences could cover legal matters, political developments, military campaigns, or philosophical reflection, and they often doubled as rhetorical performances meant to project the sender’s virtue, intellect, and political acumen.12 The act of writing and receiving letters was not merely utilitarian but served as a social ritual reinforcing bonds of amicitia (friendship) and clientela (patronage).

The letters of Cicero offer one of the most revealing windows into how elite networks functioned during the late Republic. His correspondence with Atticus, Brutus, and various provincial governors reveals how political news traveled faster through personal relationships than through official channels. These letters were also vehicles for Cicero to offer or request favors, to build consensus, or to negotiate alliances. Trust and reliability were essential in these exchanges; a well-placed correspondent could provide critical updates on the moods of the Senate or the loyalties of provincial commanders. As such, elite letters often had the feel of informal intelligence reports. Cicero’s exchanges illustrate that even in a vast and sophisticated empire, personal reputation and trust remained the currency of power.13

Private correspondence also served as a medium through which Roman elites participated in collective memory and literary culture. The practice of archiving letters and sometimes editing them for future publication was common, especially when a writer hoped to influence posterity. Pliny the Younger, for instance, curated his letters into books, which he sent to friends for circulation. His letters describe everything from the eruption of Vesuvius to Senate debates under Trajan, but they are also highly stylized and self-conscious, reflecting the author’s desire to model Roman virtues and civic responsibility.14 These edited letters became public artifacts, allowing elites to shape their legacy and contribute to the ideological production of the Roman ruling class. In this way, epistolary culture blurred the lines between private intimacy and public display.

The physical logistics of private correspondence in Rome were equally significant. There was no state-run postal system for private citizens; instead, letters were carried by trusted slaves, freedmen, or business associates, often with oral messages attached to clarify or supplement the written text. The success of a correspondence network depended on access to reliable couriers and a well-connected web of households and villas stretching across the empire on the Cursus Publicus. This infrastructure ensured that elite families remained informed and interconnected, regardless of distance. For instance, senators in Rome could communicate regularly with relatives and allies stationed in Gaul or Asia Minor, coordinating actions and opinions long before formal decrees or official envoys arrived.15 The ability to maintain such communication was both a marker of elite status and a practical necessity for managing estates, influence, and reputation.

Private correspondence among Roman elites was not an ancillary feature of political life but one of its essential underpinnings. Through letters, aristocrats exercised soft power, maintained loyalty, gathered intelligence, and curated their identities. The fluidity between private communication and public consequence is a hallmark of Roman elite culture, emphasizing how information in antiquity was managed through relationships rather than institutions. Far from being isolated missives, these letters formed a living web of influence that spanned cities, provinces, and generations.16 They underscore the Roman conviction that effective rule—and indeed, personal survival in the volatile world of Roman politics—depended as much on interpersonal networks as on legal authority or military might.

Oratory and Public Speech

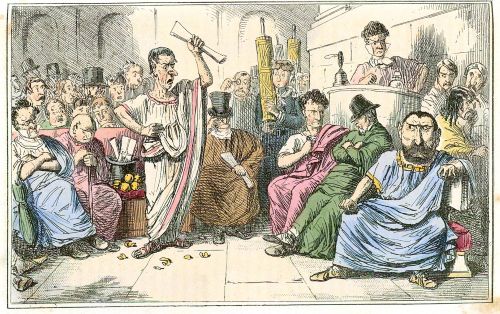

In the public and political life of ancient Rome, oratory was not merely a means of communication—it was the very lifeblood of civic engagement and elite competition. The Roman Republic was a society where spoken persuasion held supreme value, especially in institutions like the Senate, the law courts, and the contiones (popular assemblies). Mastery of oratory was a prerequisite for any ambitious Roman aristocrat, and rhetorical prowess could make or break a political career. From the early Republic through the imperial period, public speaking remained central to the performance of Roman identity and the projection of authority. The art of oratory was not an abstract skill but a lived practice tied intimately to social status, education, and public visibility.17

The most celebrated example of Roman oratory is Marcus Tullius Cicero, whose career was both made and immortalized by his rhetorical skill. As a novus homo (new man) without noble ancestry, Cicero relied on his forensic eloquence to climb the cursus honorum and gain a foothold in Rome’s elite circles. His speeches—whether defending clients in court, prosecuting political enemies, or debating in the Senate—demonstrate a fusion of Greek rhetorical theory with Roman political pragmatism. In his orations, Cicero appealed not only to logic (logos) and emotion (pathos), but also to Roman ideals such as virtus, pietas, and auctoritas. His surviving speeches, like the Catilinarians and the Philippics, are carefully constructed works of political theater, meant both to sway immediate audiences and to resonate with posterity.18

Oratory served not only as a political tool but as a form of civic education. Young Roman elites were trained in rhetoric through rigorous study of declamation and imitation of Greek masters such as Demosthenes and Isocrates. Rhetorical training began in the ludus and continued through study with grammatici and rhetoricians, culminating in public performance. Schools emphasized the suasoriae (deliberative speeches) and controversiae (mock legal arguments), which prepared future statesmen for real-world speaking engagements. Quintilian’s Institutio Oratoria, a foundational text on rhetorical education, underscores the moral and civic dimensions of oratory, urging teachers to cultivate not only skilled speakers but good men.19 In this way, Roman oratory was as much about ethics and persona as it was about persuasion.

Public speech extended beyond the courtroom or Senate chamber into the Roman Forum, the stage for political life. During Republican elections and legislative debates, magistrates and candidates addressed the populus Romanus in open-air gatherings. These speeches were crucial for rallying support, shaping public opinion, and contesting policy. Even after the establishment of the Principate, emperors understood the importance of public address. Though the Senate’s influence waned and oratory became increasingly ceremonial, emperors like Augustus and Trajan still used speeches to legitimize their rule, announce military victories, or promote moral legislation.20 Inscriptions and panegyrics from the imperial period reflect the continued symbolic power of public speech, even as its practical function declined.

Despite its high status, Roman oratory was not without critics. Tacitus lamented the decline of authentic rhetorical engagement under the empire, arguing that fear and imperial censorship had stifled free expression. By the second century CE, oratory had become more performative and stylized, exemplified by the so-called “Second Sophistic” movement. Figures like Fronto and Aelius Aristides gave elaborate declamations more for aesthetic effect than political purpose. Nevertheless, the legacy of Roman oratory endured in both its texts and ideals. It remained a core element of Roman education and continued to shape political discourse in the West for centuries to come.21 The Roman valorization of public speech as a medium of civic action and personal distinction left an indelible imprint on the history of political communication.

Heralds, Town Criers, and Public Notices

The dissemination of information in ancient Rome was not confined to the written word. In a society with varying levels of literacy and a vast, dispersed population, oral announcements played a crucial role in communicating official decrees, legal rulings, and civic news. Heralds (praecones) and town criers were employed by magistrates and civic institutions to announce events such as auctions, games, legal proceedings, and new laws. These figures served as an essential component of Rome’s public information system. Their presence in marketplaces, forums, and other public venues meant that news could reach a broad segment of the population, regardless of literacy status.22 Unlike the Acta Diurna or posted edicts that required physical presence and reading ability, the proclamations of heralds were mobile and accessible, carried by the human voice through the crowded streets and squares of Rome.

The praeco had a formal role in Roman society and was often attached to a magistrate’s staff or a public office. Their duties were multifaceted: beyond announcements, they summoned citizens to assemblies, declared the names of candidates during elections, and read out judicial sentences. In courtrooms, they called litigants and witnesses, functioning much like modern court clerks. They were also employed in public auctions (auctio publica), where their clear enunciation of items for sale and bidding rules was crucial. Though the office of praeco was considered a low-status profession—Cicero, for instance, used it derogatorily—it was nonetheless indispensable to the functioning of Rome’s administrative and legal apparatus.23 Their voices carried authority delegated from the state, and their public role enabled the projection of state power into everyday civic life.

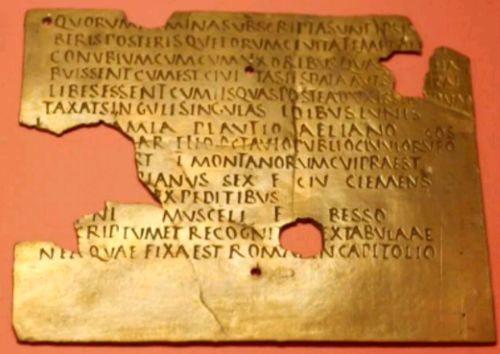

Closely associated with heralds were the postings of written public notices on tablets (tabulae) in frequented spaces like the Forum Romanum, basilicas, or other civic buildings. These notices were often read aloud by criers, especially when addressed to large audiences or when the content required explanation. The combination of oral and visual mediums helped ensure comprehension. Topics included notices of public assemblies, gladiatorial games, grain distributions, and edicts by local magistrates or the emperor. In provincial towns, praecones often functioned under the supervision of local curiae or town councils, extending this Roman mode of communication throughout the empire.24 Such practices demonstrated the Roman commitment to visibility and performativity in governance, ensuring that rule was not only enacted but seen and heard by the governed.

The Roman state also utilized heralds in military and religious contexts. Military heralds relayed commands on the battlefield and delivered declarations such as truces or surrenders. In religious ceremonies, praecones announced the beginnings of sacred rituals, processions, or public sacrifices. During major festivals like the Ludi Romani, criers informed the public of schedules, seating arrangements, and changes in venue, highlighting the logistical complexity of Rome’s public events. The auditory experience of Roman life—punctuated by the voices of heralds echoing across forums and amphitheaters—formed a constant backdrop to civic engagement.25 The praeco became a symbolic voice of the state, binding the citizenry through a shared rhythm of announcements and proclamations that marked the public calendar.

Despite the shift toward written administration under the Empire, heralds and town criers remained vital for broadcasting imperial messages. Emperors issued rescripts and edicts that were read publicly to ensure obedience and awareness across far-flung provinces. The fusion of imperial authority with local performance was key to Roman rule. Inscriptions from places like Pompeii suggest that even municipal election campaigns relied on criers to amplify candidates’ names and slogans.26 Far from being archaic holdovers, heralds adapted to the needs of a bureaucratic empire by continuing to serve as an essential conduit between the governing and the governed. Their enduring presence reflects the pragmatic Roman understanding that effective communication must be multimodal—heard as well as seen.

Coinage and Iconography as News

Roman coinage was more than a medium of economic exchange—it served as a portable form of propaganda and a dynamic vehicle for disseminating official narratives across the empire. The ubiquity of coins, their durability, and their circulation among all social strata made them uniquely suited for transmitting messages of power, legitimacy, and achievement. Roman officials, particularly emperors and magistrates, harnessed coin iconography to announce military victories, succession plans, divine favor, and public works. Every coin bore the authority of the state, and its imagery was carefully curated to shape public perception, reinforcing the ideals and accomplishments of those in power.27 In an empire where direct access to the emperor was limited, coins functioned as miniature monuments, ensuring the ruler’s presence and message were constantly visible.

Emperors frequently used coinage to publicize military conquests and foreign diplomacy. A coin minted under Vespasian, for instance, commemorates the Judean campaign with the inscription Iudaea Capta and the image of a mourning Jewish woman beneath a Roman trophy.28 This visual message conveyed Roman supremacy to both domestic and provincial audiences. Similarly, coins issued by Trajan proclaimed his Dacian victories, often depicting the conquered peoples in stereotypical submissive poses. These designs were not mere ornamentation; they served as visual bulletins of imperial triumphs. The fact that such announcements were made through coinage illustrates the Roman state’s strategic understanding of media as a means of broadcasting “news” across diverse and dispersed populations.

Coinage also offered a mechanism for shaping imperial succession narratives. Emperors often minted coins featuring their designated heirs, sometimes with joint portraits or the titles Caesar and Augustus, to communicate continuity and dynastic stability. This was particularly critical in periods of transition or political uncertainty. For example, coins of Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus jointly presenting themselves as co-rulers were part of a broader campaign to legitimize their dual rule after Antoninus Pius’ death.29 Even when emperors faced opposition or civil strife, coins projected images of unity and divine sanction. By standardizing these depictions across the empire, the state was able to assert a consistent political message regardless of local conditions.

Religious iconography on coins also played a vital role in shaping Roman civic and cultural values. Deities like Jupiter, Mars, Roma, and Victory were commonly featured, reinforcing the sacred foundations of imperial authority. Augustus famously used coins to promote the restoration of traditional Roman religion, including images of temples, priestly regalia, and symbols like the lituus (augural staff). Through such motifs, the emperor tied his reign to divine favor and ancestral traditions.30 In a world where visual cues were more immediate than textual decrees, this use of sacred imagery helped elevate imperial acts to the level of myth, making governance appear not just political but cosmic in scope.

The regular issue of coins with changing reverse types served a quasi-journalistic function. By updating coin designs to reflect current events—be it a new road project, a grain dole, or a civic celebration—Rome could keep its citizens informed in a manner that was both efficient and ideologically charged. Unlike written proclamations or spoken announcements, coins were mobile, durable, and required no intermediary. Their messages endured long after the events they commemorated. In this way, Roman coinage functioned as a form of state-sponsored “news,” visually broadcasting developments from the capital to the furthest provinces and embedding them in daily economic transactions.31 The Roman mint thus served not only fiscal needs but communicative ones, enabling the imperial voice to echo in the hands of every subject.

Imperial Control and Censorship

The Roman Empire maintained its stability through an intricate balance of authority, spectacle, and information control. As the imperial system matured, especially under Augustus and his successors, censorship became a central instrument in shaping public discourse and preserving the emperor’s image. While the Republic had mechanisms for regulating speech through laws like maiestas (treason), the Principate expanded these into tools of suppression against dissent, criticism, or even satire. Writers, orators, and politicians were acutely aware of the boundaries imposed upon free expression. Tacitus, for instance, famously lamented the dangers of speaking truth under despotism, reflecting a widespread recognition of imperial surveillance over intellectual life.32 In a society where honor and reputation were paramount, such control was not only physical but deeply psychological.

One key mechanism of imperial censorship was the expansion of the law of maiestas, or treason. Initially intended to protect the Roman state, it evolved under emperors like Tiberius into a legal catch-all used to prosecute offenses against the emperor’s dignity. This broad interpretation enabled the state to suppress a wide range of behavior, from overt conspiracies to seditious remarks or unflattering literature. Historians such as Suetonius and Cassius Dio recount the chilling effect this law had on Roman elites, with informants (delatores) flourishing under imperial favor. Writers like Cremutius Cordus, whose historical works praised the assassins of Caesar, were accused under maiestas and forced to commit suicide, while their works were publicly burned.33 The fate of Cordus exemplifies how tightly the boundaries of historical narrative were patrolled by imperial authority.

Control over literature extended into the very institutions that preserved Roman cultural memory. Imperial libraries, particularly under Augustus and later Hadrian, became not only repositories of knowledge but instruments for curating acceptable histories. While Augustus famously collected the works of poets and historians, he also expunged or suppressed writings that challenged his political narrative. The poet Ovid’s exile by Augustus, allegedly for carmen et error (a poem and a mistake), remains one of the most evocative examples of this censorship. Though the exact cause is debated, Ovid’s Ars Amatoria—a poetic guide to seduction—was clearly at odds with Augustus’ moral legislation and ideological program of mos maiorum (ancestral customs).34 Censorship, then, was often exercised through omission and exile, as much as through force or law.

The emperor also exercised control over public monuments, inscriptions, and coinage—domains that merged censorship with propaganda. Damning of memory (damnatio memoriae), the posthumous erasure of disgraced figures from public record, was among the most visible and symbolic forms of censorship. Statues were defaced, inscriptions chiseled out, and names removed from official documents. While not universally enforced, this practice signaled an attempt to edit collective memory. The Senate’s condemnation of emperors like Domitian and Commodus led to widespread iconoclasm sanctioned by the state.35 This form of control illustrates how censorship in Rome was not limited to suppressing the present but extended into rewriting the past to secure the legitimacy of successors and uphold imperial ideals.

Despite the oppressive potential of imperial censorship, it also provoked subtle forms of resistance and adaptation. Writers developed rhetorical strategies—such as irony, ambiguity, and coded language—to express dissent while avoiding punishment. Tacitus’ oblique criticisms and Suetonius’ gossipy style allowed them to comment on tyranny without direct confrontation. Pliny the Younger’s letters similarly reflect a careful negotiation between loyalty and independence. These adaptive tactics attest to a dynamic relationship between power and expression in Rome: censorship was not a static imposition but a dialogue between ruler and subject, with each seeking to control or subvert the public record.36 The result was a literary culture deeply attuned to the politics of speech and silence—one where information was not only shared, but shaped, sanctioned, and sometimes silenced.

Conclusion

The Roman world developed a multifaceted system of news communication that balanced oral, written, visual, and symbolic methods. Far from being a passive process, the communication of news in ancient Rome was active, strategic, and deeply embedded in the social and political fabric of the empire. Whether carved on stone, whispered in the Forum, or stamped on a silver denarius, Roman “news” was always more than information—it was power. In studying the Roman mechanisms of communication, we not only gain insight into their administrative sophistication but also into the enduring human need to know—and to control what others know.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, Rome’s Cultural Revolution (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 182–184.

- Cicero, Letters to Atticus, trans. D. R. Shackleton Bailey (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999), 1.5–1.6.

- Virgil, Aeneid, trans. Robert Fagles (New York: Viking Penguin, 2006), 4.173–183.

- Tacitus, Annals, trans. A. J. Woodman (Indianapolis: Hackett, 2004), 1.5–1.6; Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, trans. Robert Graves (London: Penguin Books, 2007), 6.19.

- Mary Beard, The Roman Triumph (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007), 23–28.

- Clifford Ando, Imperial Ideology and Provincial Loyalty in the Roman Empire (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000), 112–119.

- Ronald Syme, The Roman Revolution (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1939), 283–284.

- Wallace-Hadrill, 178–180.

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History, trans. H. Rackham, vol. 2 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1938), 13.84.

- Harold B. Mattingly, “The Acta Diurna and the Public in Ancient Rome,” Journal of Roman Studies 78 (1988): 3–16.

- Clifford Ando, Imperial Ideology and Provincial Loyalty in the Roman Empire (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000), 97–100.

- Peter White, Cicero in Letters: Epistolary Relations of the Late Republic (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 3–5.

- Cicero, Letters to Atticus, 2.1–2.4.

- Pliny the Younger, Letters, trans. Betty Radice (London: Penguin Books, 1969), 1.6; 6.16.

- Paul Veyne, Roman Empire (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1987), 76–78.

- Mary Beard and Michael Crawford, Rome in the Late Republic (London: Duckworth, 1999), 46–49.

- Catherine Steel, Roman Oratory (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 1–3.

- Marcus Tullius Cicero, Selected Political Speeches, trans. Michael Grant (London: Penguin Books, 1969), 89–92.

- Quintilian, Institutio Oratoria, trans. Donald A. Russell (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001), 2.1.1–2.1.25.

- Fergus Millar, The Emperor in the Roman World (31 BC – AD 337) (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1977), 144–147.

- Tacitus, Dialogus de Oratoribus, trans. Michael Winterbottom (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001), 36–38.

- Wallace-Hadrill, 167–170.

- Marcus Tullius Cicero, Pro Cluentio, trans. H. Grose Hodge (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1927), 64–65.

- Robert Knapp, Invisible Romans (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2011), 92–94.

- Harriet I. Flower, The Art of Forgetting: Disgrace and Oblivion in Roman Political Culture (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 104–106.

- E. S. Ramage, Urbanitas: Ancient Sophistication and Refinement (New York: Garland Publishing, 1991), 211–213.

- Harold Mattingly, Roman Coins from the Earliest Times to the Fall of the Western Empire (London: Methuen, 1928), 145–147.

- Richard Abdy, Roman Imperial Coinage, Volume II: Vespasian to Hadrian (London: Spink, 2012), 23–26.

- Andrew Burnett, Coinage in the Roman World (London: Seaby, 1987), 74–76.

- Zanker, Paul. The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus, trans. Alan Shapiro (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1988), 65–69.

- Erika Manders, Coining Images of Power: Patterns in the Representation of Roman Emperors on Imperial Coinage, AD 193–284 (Leiden: Brill, 2012), 51–56.

- Tacitus, Annals, 3–5.

- Suetonius, Tiberius, 61; Cassius Dio, Roman History, 57.24.

- Ovid, Tristia 2.1–2, trans. A. D. Melville (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990); Galinsky, Augustan Culture, 232–237.

- Flower, 88–93.

- A. J. Woodman, Tacitus Reviewed (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 121–128.

Bibliography

- Abdy, Richard. Roman Imperial Coinage, Volume II: Vespasian to Hadrian. London: Spink, 2012.

- Ando, Clifford. Imperial Ideology and Provincial Loyalty in the Roman Empire. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

- Beard, Mary. The Roman Triumph. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007.

- Beard, Mary, and Michael Crawford. Rome in the Late Republic. London: Duckworth, 1999.

- Burnett, Andrew. Coinage in the Roman World. London: Seaby, 1987.

- Cassius Dio. Roman History. Translated by Earnest Cary. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1914.

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius. Letters to Atticus. Translated by D. R. Shackleton Bailey. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999.

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius. Pro Cluentio. Translated by H. Grose Hodge. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1927.

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius. Selected Political Speeches. Translated by Michael Grant. London: Penguin Books, 1969.

- Flower, Harriet I. The Art of Forgetting: Disgrace and Oblivion in Roman Political Culture. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006.

- Galinsky, Karl. Augustan Culture: An Interpretive Introduction. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996.

- Knapp, Robert. Invisible Romans. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2011.

- Manders, Erika. Coining Images of Power: Patterns in the Representation of Roman Emperors on Imperial Coinage, AD 193–284. Leiden: Brill, 2012.

- Mattingly, Harold B. “The Acta Diurna and the Public in Ancient Rome.” Journal of Roman Studies 78 (1988): 3–16.

- Mattingly, Harold. Roman Coins from the Earliest Times to the Fall of the Western Empire. London: Methuen, 1928.

- Millar, Fergus. The Emperor in the Roman World (31 BC – AD 337). Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1977.

- Ovid. Tristia. Translated by A. D. Melville. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990.

- Pliny the Elder. Natural History. Translated by H. Rackham. Vol. 2. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1938.

- Pliny the Younger. Letters. Translated by Betty Radice. London: Penguin Books, 1969.

- Quintilian. Institutio Oratoria. Translated by Donald A. Russell. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001.

- Ramage, E. S. Urbanitas: Ancient Sophistication and Refinement. New York: Garland Publishing, 1991.

- Steel, Catherine. Roman Oratory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- Suetonius. The Twelve Caesars. Translated by Robert Graves. London: Penguin Books, 2007.

- Syme, Ronald. The Roman Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1939.

- Tacitus. Annals. Translated by A. J. Woodman. Indianapolis: Hackett, 2004.

- Tacitus. Dialogus de Oratoribus. Translated by Michael Winterbottom. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001.

- Veyne, Paul. Roman Empire. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1987.

- Virgil. Aeneid. Translated by Robert Fagles. New York: Viking Penguin, 2006.

- Wallace-Hadrill, Andrew. Rome’s Cultural Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- White, Peter. Cicero in Letters: Epistolary Relations of the Late Republic. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Woodman, A. J. Tacitus Reviewed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

- Zanker, Paul. The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus. Translated by Alan Shapiro. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1988.

Originally published by Brewminate, 05.21.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.