People shifted between certain partly parallel patterns of religious experience, beliefs, and behaviour.

By Dr. Andreas Nordberg

Professor of History of Religions

Stockholm University

Introduction

Over the last two or three decades, chronological, spatial and social religious variation has been an increasingly significant area of study in the research into pre-Christian Scandinavia among archaeologists, historians of religion, folklorists and researchers in sacred place-names. One important aspect of religious variation, which however has rarely been emphasized in Old Norse studies, is that even individual people usually lack a uniform system of religious beliefs and practices, alternating instead between certain more or less incongruent or even inconsistent subsystems or configurations of religious thought, behaviour and references of experience. Such forms of personal alternation between complexes of religious beliefs and behaviour usually occur spontaneously and instinctively. Often, the parallel frames of experience are closely associated with corresponding socio-cultural spheres in the person’s own life world, relating, for example, to varying types of subsistence and cultural-ecological milieus, or memberships and activities within different social groups.

Anthropological researchers of religion have for a long time emphasized such forms of individual alternation between different religious identities. For students of Old Norse religion, however, observing similar variations is much more difficult. While anthropologists may gain detailed personal data from their informants by a variety of means and methods, the researcher into Old Norse religion lacks such possibilities. Does this mean that this aspect of religious variation is in fact impossible to study for the researcher into Old Norse religion? Maybe not. In the present paper, I suggest that existing sources on Old Norse religion may actually indicate that people shifted between certain partly parallel patterns of religious experience, beliefs and behaviour. Below, I refer to these patterns as religious configurations.

Religious Configurations – A Suggested Framework

I understand a socio-cultural configuration to be a relative and functionally dynamic arrangement of socio-cultural parts or elements that make up a whole. It is a pattern of thought, behaviour, emotions, and sometimes spatial movement, which reflects cultural values, norms and perception of reality, and as such defines a framework for action. By religious configurations then, I mean concurrent complexes of religious beliefs, religious practices and frames of experience which are related to certain corresponding socio-cultural settings, forms of subsistence and spatial cultural-ecological milieus.

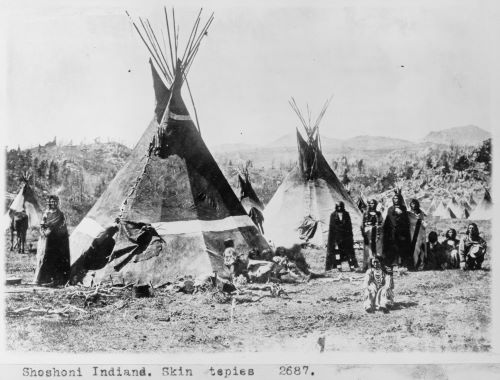

As far as I know, the first researcher to study this phenomenon focusing particularly on religion was Åke Hultkrantz, who identified three parallel “coherent systems of religious elements”, or “configurations of religious beliefs”, in the lived religion of the Wind River Shoshoni in Wyoming, USA. These configurations were related to the hunter’s vision quest, the Sun dance, and the telling of myth. When one of these concurrent configurations dominated over the other two, it momentarily displaced these in the area of active belief. The decisive factor triggering this domination was each configuration’s functional association with a dominant social situation.2 Since Hultkrantz was particularly interested in the cognitive and intellectual attitude among the Shoshoni to the incoherent relationship between their in a strictly logical sense incompatible religious configurations, it might be worth relating his study in some detail.

The Shoshoni were fundamentally a hunting community, and, as in so many other hunting cultures, the individualism of the hunter was a prominent feature. The core of the hunter’s configuration of religious belief consisted of the vision quest, associated with a category of nature and animal spirits called puha. The most significant of these were Lightning, Thunderbird and Eagle. The vision quest took place in isolated locations that were often associated with mythical stories and decorated with rock carvings of animals, in whose forms the spirits could make themselves known. During the visionary trance, the spirits transferred their powers to the hunter and guaranteed him hunting luck. As the Shoshoni increasingly became a warrior community that lived off hunting buffalo on the prairies, their needs for cohesion and social organisation grew. This was manifested in the Sun Dance, which took place within the community and actualised a different configuration of religious belief. At its centre stood the Supreme Being Tam Apö, who was identified with both the sky and a power behind the sky. Tam Apö was the creator of the universe, the upholder of cosmic order and a guarantor of the prosperity of the tribe. The Sun Dance also involved Mother Earth, the personification of the living earth itself, and the Buffalo, which presided over the buffalo herds of the prairies and provided people with food and hides for clothes.

The Sun Dance and the vision quest brought two religious configurations to the fore that were largely logically incongruent. In the hunter configuration, Lightning and Thunderbird were ranked the highest in the hierarchy of spirits. In the Sun Dance configuration, the highest in rank was the Supreme Being Tam Apö. The Sun Dance did not concern the puha spirits, while the Supreme Being and Mother Earth played no part in the vision quest. According to Hultkrantz, there appears to have been no attempt to relate or compare the highest beings from each religious configuration to each other.

Mythical storytelling further increased this incoherence. The mythical configuration was brought to the fore mainly during the winter months when the Shoshoni spent a large part of their time together indoors. Although the mythical stories were often entertaining and full of humour and epic embellishment adapted to the audience at the time, most storytellers maintained that the myths were, as they called them, “true stories”. These stories were set long ago in a legendary time, when a series of supernatural beings, the foremost of which were Wolf and Coyote, inhabited the world. Assisted by Coyote, Wolf was the creator of animals and humans, the order of nature and the prerequisites for life, but he was also the instigator of death. However, even in this case there were no established ideas about, for example, how Wolf in the mythical configuration related to Tam Apö of the Sun Dance configuration, or Lightning and Thunderbird of the hunter configuration. The Shoshoni people perceived these three parallel belief complexes separately as equally true and logically cohesive, as they were related to different social and cultural-ecological settings.

Analogous phenomena have also been observed elsewhere. For example, Stanley Tambiah has emphasized that villagers in rural Thailand switch between what he viewed as four distinct “ritual complexes” of both Buddhist and indigenous traditions, which are nevertheless linked together in “a single total field”.3 An example from closer to home is given by Matti Sarmela, who claims that Finnish pre-Modern popular culture and popular religion consisted of three major tradition-ecological segments or “cultural systems”, historically linked to hunting, slash-and-burn cultivation and agricultural farming.4 Similarly, during his anthropological fieldwork among the Bambara and Mandinka in Mali, the historian of religion Tord Olsson observed that the lived religion of these peoples is structured into three overall “ritual and mythical fields”, linked to farming, hunting and spirit possession, and that “people, in many cases the same individuals, are moving between these fields”. The ritual field related to farming is centred on the village and its surrounding arable land and is characterised by ancestor worship, secret societies and a complex cosmological tradition linked to the farmer’s activities, life cycles, marriage, as well as a body of conceptions about the Supreme Being and Creator, and other beings created by him. The hunter’s ritual field, by contrast, primarily uses the bush as its arena. Here the cult is mainly focused on certain spirits called Djinns, believed to live in the bush and roam around near villages and farmland, as well as a pantheon of deities that has no direct significance in the ritual field of farming. The Djinns, finally, are also at the centre of the third ritual field related to spirit possession.5

The concepts religious configuration, complex, system, and field used in the referred studies,are semantically synonymous. The limited scope of this paper restrains me from referring to further parallels from around the world (although it should be noted that such phenomena are by no means exceptional). Instead, on the basis of the examples already given, it is possible to outline the contours of a more general framework of the alternation between religious configurations, for example:

- That religion is not a uniform or homogeneous system, either in a society as a whole, or in the arrangement of religious beliefs and behaviour of individual people or groups.

- That the lived religion is an integrated part of everyday life, and is consequently formed (and transformed) by people’s day-to-day livelihoods, subsistence and affiliation to social groups.6

- That religious beliefs and behaviour relating to correspond-ing forms of subsistence and social and cultural-ecological milieus, may form into parallel religious configurations.

- That people, both individually and as social groups, may alternate between these different religious configurations, and that a decisive factor in these alternations is the person’s or the group’s movement between the corresponding social and cultural-ecological settings.

- That the beliefs and practices of the religious configuration that temporarily dominate a person’s active belief, may momentarily displace the beliefs and behaviour of other religious configurations.

Religious Configurations in Late Iron Age and Viking Age Scandinavia

Can the general framework of religious configurations, as outlined above, be applied as a form of lens or raster through which we may study Old Norse religion? And if so, may this lens reveal some sort of parallel religious configurations even in Late Iron Age and Viking Age Scandinavia? In my opinion, it can and it does. I suggest that there existed at least three major religious configurations in Scandinavia during this period: the religious configuration of the farmstead community, the religious configuration of the hunting and fishing grounds, and the religious configuration of the warband institution. In addition to this, one could argue for the existence of a fourth mythological configuration as well, although this would partly coincide with the religious configurations of the farmer and of the warrior.

There is, of course, an obvious chronological layering between these suggested religious configurations. Hunting and fishing are much older livelihoods than farming, which in turn spread to Scandinavia several thousands of years before the rise of the aristocratic warband institution during the Early Iron Age. However, since this cultural historical development involves an unmanageably large timescale,7 I will settle for the observation that the suggested three or four religious configurations existed in parallel in Scandinavia during the Late Iron Age and the Viking Age.

Furthermore, Scandinavia constitutes a very large geographical area, and encompasses natural environments which vary from region to region. Since these shifting ecological conditions affected people’s day-to-day subsistence, and since religion was an integrated part of everyday life, obviously Scandinavia’s shifting cultural-ecological milieus indirectly allowed considerable reli-gious variation. Hence, although I maintain that the suggested religious configurations were common throughout the Germanic parts of Scandinavia, there must have existed extensive regional variations, both within each religious configuration, and in the significance of one religious configuration in proportion to the other.

Finally, each of the religious configurations encompassed numerous beliefs and traditions of varying origin, and any effort to summarize all of their aspects and characteristics in only a few pages will inevitably lead to an all too simplified result. However, since the primary objective and motivation of this paper is to introduce an alternative theoretical and methodological perspective of religious variation into the research of Old Norse religion, and since I for the sake of this argument nevertheless need to present such summaries below, I will focus only on the core or seman-tic centre of each of the religious configurations.

The Religious Configuration of the Farmstead Community

The most basic social foundations in Late Iron Age society in Scandinavia were the communities of the family and lineage, the farmstead, and the local settlement area. The households of both the aristocracy and the peasants were fundamentally self-sufficient through farming, animal husbandry, hunting and fishing. Livelihoods and the annual agricultural cycles constituted a shared dominating interest8 for the whole community, and this common ground was also reinforced by the fact that many peasants lived directly adjacent to the large aristocrats’ farms and were linked to them through work and possibly tenancies, etc.

The religious configuration of the farmstead community involved more or less all people, i.e. women and men of all ages and social classes. It encompassed much of what in a broad sense related to the maintenance of a good life, such as cosmic order and regeneration, societal stability and peace, agriculture and stock raising, prosperity, pregnancy and birth, puberty rituals, marriage, and other phases of the life-cycle, health, illness and remedies, death and burial, the relationship to the dead, as well as all of the religious beliefs and daily ritual behaviour associated with the many aspects of the domestic household, the farmstead and its infields. Unfortunately, due to the lack of sources our knowledge of the domestic side of the configuration of the farmer is rather scant. But it should be noticed that the evidence that we do have on the domestic religion for the most part does relate to the areas just mentioned.9

Fortunately, there is more information about the public dimension of the religious configuration of the farmstead community. The hope and aspiration for cosmic order, prosperity and the regeneration of the crop and animal stock, as well as the well-being of land and people, obviously comprised the semantic centre of this religious configuration. This is apparent for example in the common pre-Christian ritual formula til árs ok friðar. The word friðr primarily refers to ‘peace, unity’, but the term also had certain sexual connotations that strengthened the ritual for-mula’s associations with regeneration and fertility. The term ár means ‘year, annual yield/harvest, yield from crops and livestock’. Semantically ár ok friðr therefore expresses the hope of a new year, annual yield/harvest, fertility and peace.10 This was also an explicit purpose of the seasonal festivals of the agricultural year, which according to several sources were celebrated til árs ‘for the harvest, annual yield,’ til árbótar ‘for better annual yield’, til gróðrar ‘for the crops’, etc.11

In addition to a variety of local deities12 and spirits related to the household, the farmstead and the arable lands (which might actually have played a more prominent part in everyday religion than did the higher gods), it is evident from both theophoric place names and literary depictions, that the public cult relating to the religious configuration of the farmstead community was above all devoted to uranic and chthonic gods such as, for example, Þórr, Ullr, Freyr, Freyja and Njǫrðr.13 The worship of Þórr and Freyr may have partly overlapped, although, judging from the distribution of the theophoric place names, at least in some areas of Scandinavia the significance of one over the other may also have varied regionally.14 In the Norse mythological sources, Þórr appears to have a special position as the protector of the cosmos and the people,15 whereas Freyr and Freyja in particular were assumed to guarantee regeneration and fertility.16 Freyr was therefore called inn fróði‘the prolific one’,17 and bore epithets such as árguð ‘god of the year’s crop’, and fégjafi ‘the bestower of fé [= cattle or riches]’.18 According to Adam of Bremen, Thor (ON. Þórr) reigned in the air and controlled thunder, lightning, wind, rain, sunshine and crops, while Fricco (i.e. OSw. Frø, ON. Freyr) “bestows peace and pleasure on mortals” (pacem voluptatemque largiens mortalibus).19 Adam’s choice of words may allude to the formula til árs ok friðar, which according to some scholars appears to have been particularly linked to the worship of Freyr and Njǫrðr.20

The fact that prosperity and regeneration constituted a dominating interest within the religious configuration of the farmstead community is also indicated by terms such as ármaðr, árguð and ársæll. The ármaðr ‘the year man, the harvest man’, was according to an Icelandic family saga a ruling spirit who ensured good yields from grain fields and livestock.21 The name árguð was, as already mentioned, an epithet for Freyr. The adjective ársæll described certain kings and noblemen, who through their inherent luck and good relationship with the gods guaranteed good years of prosperity for the land and its people.22 In this role, the ársæll ruler and Freyr the árguð carried similar functions.23 The latter is related to the fact that aristocrats were expected to manage the public sanctuaries and uphold the public worship on behalf of the people and the land. Several Old Norse sources even state that the gods were deemed able to turn against the people and punish them with bad years and crop failure if the nobles did not fulfil their duties.24

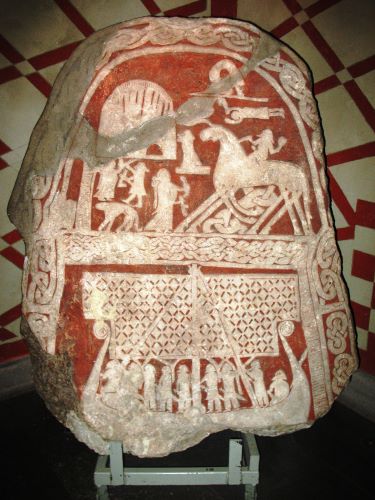

Probably, the inscription on a 7th-century rune stone in Stentoften in Blekinge province, Sweden, relates to this cultic task of the aristocracy. An extract from the text reads:

niuhAborumRniuhagestumRhAþuwolAfRgafj

niu habrumR, niu hangistumR, HaþuwulfR gaf j

[With] nine goats, nine stallions, HaþuwulfR gave year [= a good annual yield].25

The final rune j in the quotation is an ideograph, referring to the word Proto-Norse jára = ON. ár ‘year, annual yield, harvest’. Thus, at some point in the 7th century, a man HaþuwulfR in Blekinge ensured a new year with a good annual yield for the land and people by sacrificing nine goats and nine horses.

The rune stone from Stentoften is, however, interesting for additional reasons. Alongside HaþuwulfR, the inscription also mentions the name HariwulfR. It is highly likely that the men carrying these names were úlfheðnar, elite warriors dedicated to the god Óðinn. The names thus remind us of a different religious configuration in Late Iron Age and Viking Age Scandinavia.

The Religious Configuration of the Warband Institution

The aristocratic warband or comitatus is very prominent in archaeological, literary and onomastic sources about Scandinavia during the Late Iron Age and the Viking Age. The embryo of this institution appears to have developed as early as in the Late European Bronze Age. Subsequently it was affected by the Celtic culture and by Roman civilisation. A central arena of the warband was the aristocratic hall, which was introduced in Scandinavia onto certain large farms in the 4th and 5th centuries AD, while in the 7th century grander halls started to appear in central-place complexes, consisting of, for example, assembly sites, marketplaces, craft sites, public sanctuaries and monumental burial mounds. In the European Migration Period the warband was a central institution among all Germanic peoples, and in Scandinavia it retained this position during the Viking Age.26

Ideologically, the most prominent arena for the warband community was the hall, where the warlord and his wife convened their retinue with feasts and rewarded the men with exchanges of gifts, in return for their promises to fight and possibly die for their lord and lady. In this respect, the ceremonial gathering in the hall constituted a social foundation of the retinue, although it was also a highly formalised religious communion, which appears to have been expressed most strongly during the fellowships of the ritual meal and especially of drinking.27

When a warrior was admitted into a warlord’s retinue, he entered into a relationship with his lord and lady that resembled adoption.28 This relationship is even reflected in the complex of myths and heroic sagas about Óðinn, who in several semi-mythical heroic poems and fornaldar sagas is portrayed as an adviser, companion or foster-father to his chosen warriors. When his warriors die, Óðinn brings them to Valhǫll, where he acknowledges them as his óskasynir ‘wish-sons’, i.e. foster-sons,29 and invites them to endless feasting and drinking in the company of his female valkyries. These epic motifs thus fundamentally reflect the communion in the aristocratic hall between the warlord, his wife, and the “adopted” men of the retinue.30

But actually the motifs may even hint at a deeper religious relationship between the warrior god and the members of the warband community. Ideally, young men had to undergo certain initiation rites before they were admitted into the warband. Even though such rites are often secret, it is evident from several sources that a vital part of the warrior initiation centred on a ritual drama during which the initiate assumed the shape of a wolf or bear, and received a new name that alluded to this therianthropic transformation.31 It is, for example, in this cultural historical context that the names HaþuwulfR and HariwulfR on the Stentoften Stone must be viewed. These two names also appear on a contemporary rune stone in Istaby, Blekinge, together with yet a third analogous name HeruwulfR. The three names correspond to a broader group of similar names testified to in a range of sources from different parts of the Germanic area, all have the final element PN. -wulfR, ON. m. úlfr ‘wolf’. The first element PN. haþu- in HaþuwulfR corresponds to ON. hǫð f. ‘battle’, and the name therefore means ‘Battle Wolf’. In HariwulfR, the first element is PN. hari-, ON. herr m. ‘war-host’, and the name therefore means ‘War-Host Wolf’. Lastly, HeruwulfR means ‘Sword Wolf’, as the first element is PN. heru-, ON. hiǫrr m. ‘sword’. Most likely these men were given their names when undergoing initiations to become úlfheðnar and admitted into a warband.32 The úlfheðnar ‘wolf-skins’ along with the berserkir ‘bear-shirts’ were the elite warriors with strong personal relations to Óðinn.

Óðinn, of course, was the god par preference of the royal and aristocratic warband institution, and he represented all the characteristics of the at times capricious life in the warband community. On the one hand, he personified all the abilities that were regarded as virtuous and coveted within the warrior aristocratic hall culture. For example, Óðinn was the god of wisdom and the god of death, because he acquired his in-depth knowledge by voluntarily dying in order to be initiated into the mysteries of the Other World, conquering the finality of death and thus being able to consult the dead for advice. He was the god of poetry, which was a highly respected art form in the aristocratic hall culture. Ideally, each warlord had at least one skald in his retinue. He was the god of the mead, the most preferable beverage in the ceremonial drinking in the hall.33 On the other hand, he was also the terrifying, erratic and deceitful god of war and as such he personified the unpredictability of violence and battle, as well as the warrior’s ecstatic rage. The latter is even reflected in his name, ON. Óðinn > PrGmc *Wōðanaz, from Óð-, *Wōð– ‘rage, fury’.34 Adam of Bremen, who in 1076 described an idol of Óðinn in the central holy place in (Old) Uppsala, emphasised this central aspect of Óðinn, relating that “Wodan, that is fury” (Wodan, id est furor).35

According to the Eddic poem Vǫluspá, Óðinn initiated the first war in the world between the two tribes of gods: the Æsir and the Vanir. From a mythical perspective this was a prototypical action.36 When battles between aristocratic warlords are depicted in Old Norse skaldic poetry, the fallen, bloodied warriors on the battlefields are often described using concepts that also occur in religious sacrificial terminology, indicating a religious aspect of the violence.37 On the one hand, slaying enemies on the battle-field could be conceived of as making sacrificial offerings to the god of war. On the other hand, death on the battlefield could be perceived as the warrior’s final reward. Through a violent death in battle, Óðinn’s initiated warriors ultimately achieved complete communion with their god.

Spatial and Mental Alternation between the Religious Configurations of the Farmstead Community and of the Warband Institution

In my opinion, the most prominent aspects of the cult of Óðinn mainly belonged to the religious configuration of the royal and aristocratic warband institution, while the cult of gods such as Þórr, Freyr, Freyja and Njǫrðr instead belonged to the religious configuration of the farmstead community, which was of major importance for everyone. Even the kings’ and the warlords’ residences were basically large farmsteads, and kings, warlords and warriors were in this sense, if not farmers themselves, at least directly dependent on the agricultural and pastoral community’s prosperity and good fortune. Cosmic and societal order, the cohesion of the family and lineage, general prosperity, regeneration and a good annual yield from crops and livestock – all these things were dominating interests for all members of the community. It was with such hopes that the kings and aristocrats represented the entire community and all its inhabitants to the gods, as they bore the cost of and even led the public cult til árs ok friðar at the communities’ common sanctuaries. And it was probably because of these social and religious functions that certain royal dynasties such as the Ynglingar of central Sweden (and later of southern Norway) claimed to be descendants of the fertility god Freyr.

The religious configuration of the farmstead community was thus of major importance for all people. But the warlords and their warriors also shifted to the religious configuration of the warband institution, which differed radically, both socially and religiously, from the farmstead’s religious configuration. Unfortunately, we know little about the attitudes of common people to the religious configuration of the warband, since the preserved Norse literary sources primarily originate from the royal and aristocratic socio-cultural milieus. Probably the set of religious traditions that constituted the semantic centre of the warband institution was of little interest outside this exclusive social stratum. Óðinn was the god of war par preference in the skaldic and mythic poetry, yet it is still possible (or even probable) that commoners also, or even rather, invoked Þórr and maybe Freyr even in case of occasional personal violent conflicts.38 When ordinary people did invoke Óðinn, they still lacked any profound personal ties to the god equivalent to those between Óðinn and the elite warriors of the aristocratic retinues. The socio-cultural centre of the most prominent aspects of the cult of Óðinn was certainly the warband institution, from which most people were excluded.

A decisive factor for the aristocrats’ and the elite warriors’ alternation between the religious configurations of the farmstead community and of the warband institution, was the functional association of each religious configuration with a corresponding dominant socio-cultural context. But these social situations did not only determine which of the religious configurations dominated and momentarily displaced the other in the area of active religious belief,39 it seems as if the alternation also activated two partly parallel social and even existential configurations of values.

For example, while the farmstead community depended on the cohesion of the family, lineage, local district and region, the aristocratic warband institution was based on the social foundations of an exclusive, initiated society which was built not on biological family ties, but instead on a pact between the warlord and lady and the warriors of the retinue. Within the religious configuration of this exclusive social framework, the members of the aristocratic warbands seem to have revered Óðinn as the only god of significance, or at least as the highest god of the pantheon, as Hávi ‘the High One’,40 Hár ‘High’,41 and Alfaðir ‘All-Father’,42 etc. Yet, in parallel with this, within the religious configuration of the farmstead community the aristocrats also led the common worship of life-affirming deities such as Þórr, Freyr, Freyja and Njǫrðr at the public sanctuaries, and in this context they honoured not Óðinn but rather Þórr or Freyr as the foremost of the gods,43 in the latter case for example as Veraldar goð ‘god of the world’,44 fólkvaldi goða ‘ruler of the gods’,45 and ása iaðarr ‘protector of the Æsir’.46 And while the worship of the gods within the religious configuration of the farmstead community was based on a need and desire for cosmic order, peace, regeneration, good health, and prosperity in this life, the semantic centre of the religious configuration of the warband institution was instead related to the constantly ongoing small-scale endemic warfare – sometimes within the warrior aristocrats’ own lineages – which ideally would end in an honourable death in battle, subsequently rewarded by a glorious existence in the afterlife.

Yet, despite these sharp contrasts – which strictly logically speaking are conflicting and inconsistent – there is no indication that these two parallel sets of religious beliefs and behaviour appear to have been perceived as contradictory, either by the warrior aristocrats themselves, or among other people of the peasant communities (to the extent that the latter were familiar with the religious configuration of the warband institution). This, I argue, was because the decisive factor for the alternation between the two parallel religious configurations was the functional association of each configuration to its corresponding social situation and socio-cultural milieu.

The Religious Configuration of the Hunting and Fishing Grounds

As suggested above, the religious configuration of the warband institution mainly belonged to the religious life of those within the higher strata of society. Most people in Late Iron Age and Viking Age Scandinavia did not usually shift to this religious configuration, since they were not a part of the warband institution’s corresponding socio-cultural milieu. I do suggest, however, that most peasants could alternate between the religious configuration of the farmstead and that of the hunting and fishing grounds.

It is not totally clear who were engaged in hunting and fishing. Probably it concerned most people in one way or the other. Some Norse sagas mention men involved in big-game hunting and deep-sea fishing in Norway and Iceland, but it is quite probable that also women and even children were engaged in small-game hunting and freshwater fishing. Admittedly, textual and archaeological sources especially relating to religious traditions associated with hunting and fishing in pre-Christian times are actually on the whole so few,47 so that the suggestion of a particular pre- Christian religious configuration associated with hunting and fishing of course is but a hypothesis. Yet, it is still absolutely reasonable to assume that a wealth of such pre-Christian religious traditions did exist. The lived religion in pre-Christian Scandinavia was an integrated part of everyday life and as such strongly associated with day-to-day sustenance. Since most people were partly dependent on the hunting and fishing economy (in the coastal regions more so than in the inland areas), this livelihood may well have been a dominating interest that could trigger a certain configuration of beliefs and practices in the lived religion. At least, this would certainly have uncountable ethnographic parallels, both in for example the religious traditions among neighbouring Baltic, Finno-Ugrian and Sámi peoples,48 and in later Scandinavian folklore and popular customs.

In all of these contexts we meet complexes of religious beliefs and ritualistic behaviour associated with hunting and fishing, that centred around ideas of, for example, omens, forewarnings and taboos, traditions concerning envy and limited goods, magical practices and ritual regulations on how to handle weapons and hunting tools, how to kill and cut up the game, and so forth. Of greatest importance is the hunter’s or fisherman’s good relationship with the supernatural lord, ruler or owner of the fish and prey of the hunting grounds and fishing waters. Corresponding notions are well documented in later Scandinavian folklore and folk customs,49 not least regarding the complex of traditions relating to the owner of nature,50 who is known in Scandinavian folklore for example as the Swedish skogsrå ‘ruler of the woods’ and sjörå ‘ruler of the lake, or fishing waters’, or havsfrun ‘the mermaid’, etc.,51 and the Norwegian huldra ‘hulder’ (ie. huld-ra ‘hidden ruler’).52 In Nordic traditions lucky hunters and fishermen were often believed to be blessed with a good relationship with the rå or the huldra. Even impersonal collectives of supernatural beings are mentioned in similar contexts,53 corresponding with the information in the Icelandic Landnámabók, from the early 13th century, that people who were blessed with hunting and fishing luck had a good relationship with the landvættir (the spirits of the land) that ruled over the hunting and fishing grounds.54

Thus, what is almost completely missing in the early sources on Old Norse religion is, interestingly enough, instead common in mediaeval and later Scandinavian folk traditions. Whatever the explanation for this might be,55 the most urgent question relating to the scope of this paper is what relevance the late evidences may have for our understanding of earlier cultural historical periods. In my view, at least it should not be totally dismissed. In his outline of a tradition-ecological and tradition-historical perspective on folk traditions, the Finnish folklorist Lauri Honko stresses that stabile social institutions, group identities, and economic utilization of the cultural-ecological milieu are of fundamental importance for the continuity of cultural traditions.56 This actually corresponds fairly well with the relative stable social and culture-ecological settings associated with hunting and fishing activities during the last millennium before the major urbanization process in the 19th and 20th centuries in Scandinavia. Thus, without in any way dis-regarding the many complex problems concerning the relation between pre-Christian religion and Mediaeval and pre-Modern folk customs, it seems more likely in my view that the later popular traditions associated with hunting and fishing at least to some extent are related to an earlier complex of ideas, rather than solely being a product of cultural inventions and influx during Catholic or Protestant times. This certainly does not mean that these late folk traditions constituted some sort of frozen, stagnated cultural survivals from pre-Christian times, in the sense early evolutionistic scholars may have understood them. Rather, I suggest that it opens up for the possibility of the existence of a similar configuration also in pre-Christian times, as this form of tradition complex was an adaptable part of the lived religion even in the medieval and late pre-Modern eras.

The latter is emphasized for example by the Swedish ethnologist Orvar Löfgren in a study of local fishing communities in Sweden and Norway in the 19th and early 20th centuries. According to Löfgren, these communities constituted “a milieu in which belief in supernatural powers associated with fishing was a living reality, and where the learning of ritual techniques and magical rules formed part of the natural socialisation process in the fishing profession”.57 The fishing milieus and fishing activities thus were related to a corresponding cognitive belief system, parallel with the Christian worldview. Löfgren continues:

Our cultural world of experience can therefore be full of inner contradictions and inconsistencies, and in addition, individuals can switch between different cultural repertoires or value systems depending on their current situation. This is the type of problem that we have encountered in the earlier discussion of how fishermen were able to be converted from sceptics to active believers following an appalling fishing season, or how Jesus and the mermaid [Sw. havsfrun] could exist side by side in the lives of fishing communities. For most fishermen, their belief in supernatural powers probably constituted a religious system that was clearly separated from the Christian worldview. These two cosmologies existed side by side as autonomous and largely contradictory moral systems, although some integration (syncretism) did occur between them.58

What Löfgren refers to as a separate, autonomous religious system relating to the fishing milieu, existing in parallel with the Christian worldview is actually more or less identical with what I am conceptualizing as parallel religious configurations. Of course, this autonomous system associated with fishing in late pre-Modern Scandinavia is not evidence of far earlier conditions. It does not prove a religious configuration associated with hunting and fishing in the Viking Age. Yet, I do propose that it does at least strengthen the possibility of a corresponding religious configuration even in pre-Christian Scandinavia. And again, what triggered this religious configuration relating to hunting and fishing in active belief – in late pre-Modern times as well as in pre-Christian periods – was its functional association with the corresponding cultural-ecological milieus of the hunting and fishing grounds, and the social situations of the lone hunter/fisher or the small hunting/fishing party.

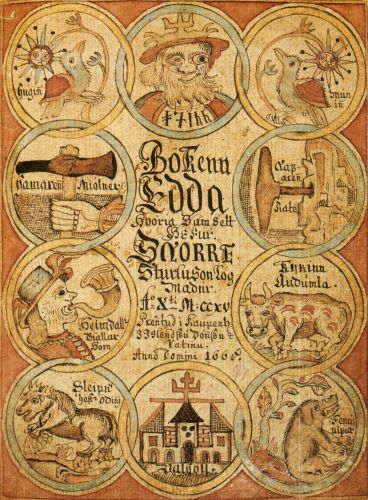

A Mythological Configuration?

It is paradoxical that so much of our knowledge of Old Norse religion is based on mythical sources at the same time as we remain largely in the dark about who the narrators of the myths were and in what context the myths were narrated.59 We do know, however, that sagas were told at major official events, feasts and in the aristocratic hall assemblies,60 and probably also in more private everyday contexts, although the latter is much more difficult to demonstrate due to the nature of the sources. Mythical storytelling probably followed roughly the same pattern. There are many indications that the mythical traditions were well known among both commoners and the elite.61 Myths were probably retold in many different contexts, in public and in the private sphere of the family, in poetic and prose forms, by professional storytellers and lay people (such as the tradition bearers of the Finnish Kalevala poetry). Through mythical associations, poetic allusions and kennings, prominent storytellers and poets linked mythical tales together in a way that in some contexts almost resembled an independent mythical dimension.

Could this be apprehended as a separate mythological configuration? Admittedly, there are many relevant objections to such a suggestion. Mythical storytelling was important in the religious configurations of the farmstead community and of the warband institution (but apparently not in that of the hunting and fishing grounds). A mythical configuration would therefore partly coincide with these. Conversely, mythology does display important aspects that are not expressed in the other religious configurations, and there is intrinsic value in highlighting these distinctive characteristics in their own right. For consistency, although there may possibly be better ways of conceptualising this, I am therefore opting to talk of a loosely formed and partly overlapping mythological configuration, with boundaries that admittedly are difficult to define.

The Old Norse myths display all the characteristics of the mythical genre in general. Through a combination of religious notions and epic motifs, a mythical universe emerges which partly resembles human society, but is also part of a totally different world. The pre-Christian gods appear in anthropomorphic form, with human traits, characteristics and emotions. In certain myths, the deities’ adventures are set in an unspecified ancient age, before humans walked the earth. In others, the gods instead interact with humans, often with the intention of confirming social norms or affecting humans’ existence in certain ways. Here the Old Norse myths are also sometimes interwoven with certain motifs from the Scandinavian-Germanic heroic tradition, in which human heroes interact with gods (usually Óðinn) and other supernatural beings in a partly mythical and partly semi-historical context. Many myths recount stories that had no or few parallels in religious practice, the central aspect instead being the actual consequences of what happened in the myth, as these occurrences shaped the world and therefore were continuously affecting people’s life worlds. Furthermore, many of the gods and supernatural beings occurring in the myths were not the subject of actual worship. These included some probably purely epic figures, such as Loki,62 as well as gods and other beings that were deemed to exist but without being the subject of active veneration. For example, the enigmatic god Heimdallr may be a representative of the latter.

Common to the world of myth is further that the gods are organised into family systems and internal relationships that are not expressed in the corresponding cult. The Greek deities, to make a comparative analogy, were systematised in mythology into a joint Olympic family pantheon, led by Zeus. But, in the lived religion of ancient Greece, the gods were generally worshipped separately, usually in separate sanctuaries and within the framework of separate feasts led by separate ritual specialists. Admittedly, some-times several deities were worshiped collectively, but in general, neither the myths’ epic dramas nor their systematised family pantheons had parallels in actual cult. The same pattern is also seen in pre-Christian Scandinavia. Although a great variety of gods, lesser deities and other beings appear in the myths, only some of them seem to have been objects of actual worship.63

Additionally, in the Old Norse myths the gods are characterised by their degree of anthropomorphic concretion, features that probably become even more accentuated by the narrators’ use of, for example, enactments, gestures, facial expressions and masks.64 Such epic motifs with the gods must not, however, be confused with a general conception (or even perception) of the gods’ essential nature. While the epic anthropomorphic form is a distinctive characteristic of the mythic genre (which was also reproduced in iconography), the same conceptions of the gods may have been expressed differently in, for example, prayers and hymns, and to an even greater extent in everyday speech, in which the gods sometimes seem to have been spoken of as an impersonal ruling collective (compare for example designations such as regin pl. ‘the rulers, leaders’, bǫnd pl. and hǫpt pl. ‘the obligators, decision makers’, etc.).65 Yet another distinctive characteristic of the mythical genre appears to be that some beings were given a higher status in the mythical world than in daily religion. One example of this is that elves and giants were portrayed in a much more elaborated and elevated manner in the myths than in medieval and later folklore. There might be several reasons for this, but in my view, the differences could be old and dependent on the various genres of lore.66

The conceptualisation of the mythical dimension of religion as an overlapping and loosely formed mythical configuration does not preclude mythical storytelling, poetry and pictorial art from featuring in other parts of religion (which also contributed to making the mythology more varied and superficially contradictory). But it does accentuate the mythical dimension’s many specific and uniting characteristics, which often differentiated mythology and mythical storytelling from other aspects of the lived religion. It also highlights the considerable significance of the situational and contextual framing of the mythical storytelling as such.

Configurations of Religion in Late Iron Age and Viking Age Scandinavia – A Conclusion

As stated in the introduction to this paper, the aim of this study is to contribute an additional theoretical perspective to the ongoing discussion about religious variation, in research into Old Norse religion. My suggestion is, that the polytheistic lived religion in Late Iron Age and Viking Age Scandinavia was not a uniform or homogeneous system, either in the society as a whole or in the individual people’s cognitive arrangement of religious beliefs and behaviour. Rather, religion was an integrated part of people’s daily life, and thus to a great extent formed (and transformed) by their day-to-day livelihoods, subsistence and affiliation to social groups. Since these fundamental social and cultural-ecological conditions were not homogeneous, the religious beliefs and behaviour formed parallel religious configurations corresponding with these variations. Above, I have proposed three such major reli-gious configurations, that of the farmstead community, that of the warband institution, and that of the hunting and fishing grounds. In addition, I have suggested that even mythic storytelling might in part have formed a similar mythological configuration.

When people moved between different social and cultural-ecological milieus, they also alternated between the correspond-ing religious configurations. The decisive factor in this alternation was the functional association between the social situation and the corresponding religious beliefs and behaviour. Consequently, most people did alternate between the religious configurations of the farmstead community and those of the hunting and fishing grounds, since both of these religious configurations related to two parallel cultural ecological milieus with major importance for their day-to-day subsistence. However, while the religious config-uration of the warband institution was of central importance to the aristocratic warrior elite, it did not usually engage ordinary people, because they were not a part of this social institution. The warrior aristocrats, for their part, probably alternated between all of the religious configurations.

Of course, structuring the lived religion in accordance with this theoretical framework is but a tentative approach to gain a deeper understanding of people and life ways in pre-Christian Scandinavia. Yet, I believe that the model has its advantages. It makes our view of the polytheistic lived religion more strongly contextualised and situated, and in addition it even helps us identify areas of the lived religion which for various reasons we still know little about.

The model of “religious configurations” offers an additional way of understanding socio-religious variation in Late Iron Age and Viking Age Scandinavia. What have sometimes been emphasised as signs of incoherence and contradictions in the preserved sources of Old Norse religion gain a logical explanation in this context. They exemplify the polytheistic lived religion’s expected natural variations.

Appendix

Endnotes

- This study is sponsored by Riksbankens Jubileumsfond / The Swedish Foundation for Humanities and Social Sciences.

- Hultkrantz 1956.

- Tambiah 1970, especially p. 370.

- Sarmela 2009; similarly Honko 1993.

- Olsson 2000, quote p. 29, translated from Swedish: “I själva verket illustrerar det religiösa livet […] tre rituella och mytiska fält […] och att människor, i flera fall samma individer, rör sig mellan dessa fält.”

- Compare the tradition-ecological and tradition-historical perspectives advocated for by for example Lauri Honko 1993:51–60.

- Compare Sarmela 2009, who does weight in a time scale of several millennia.

- The concept of dominant or dominating interests was first coined by the ethnologist Albert Eskeröd, who defined it as “the foundation for the growth of ideas of the supernatural relationships between the different needs of human beings grouped together and the environment” (1964:85).

- Compare for example DuBois 1999; Steinsland 2005:327–356; Carlie 2004; Murphy 2018.

- Hultgård 2003; Nordberg 2006:84–86.

- Cf. Beck 1967:48–57, 89–90; Nordberg 2006:76–77 with references.

- Cf. Hultgård 2001.

- Vikstrand 2001; Brink 2007. For simplicity I use the Old Icelandic forms of the gods’ names for the entire Nordic region.

- Sundqvist 2016:516–519.

- Bertell 2003.

- Steinsland 2005:143–164, 195–207.

- Skírnismál st. 1, in Neckel/Kuhn 1983:69.

- Skáldskaparmál Ch. 7, in Faulkes 1998:18.

- Gesta Hammaburgensis IV, 26, in Schmeidler 1917.

- Wessén 1924:126–130, 177–183.

- Krístni saga Ch. 2, in Guðni Jónsson 1968.

- Sundqvist 2016:462–464.

- Sundqvist 2014.

- Sundqvist 2016:241–258.

- Interpretation and translation following Santesson 1989, supported by e.g. McKinnell & Simek & Düwel 2004:54–56; Schulte 2006.

- Enright 1996; Herschend 1998:14–49; Brink 1999.

- Brady 1983; Enright 1996:69–96; Nordberg 2004:177–198.

- Brady 1983:215–216; Enright 1996:74–77.

- Gylfaginning Ch. 20, in Faulkes 1988:21.

- Nordberg 2004:153–223.

- Blaney 1972:64–129.

- Sundqvist & Hultgård 2004.

- For surveys of Óðinn’s many aspects, cf. Turville-Petre 1964:35–74; Steinsland 2005:165–194. For the significant connection between Óðinn and the ruler ideology among kings and aristocrats, cf. Schjødt 2007.

- de Vries 1962:416.

- Gesta Hammaburgensis IV, 26, in Schmeidler 1917.

- Nordberg 2004:92–120.

- Beck 1967:117–177.

- Compare Schjødt 2012; Sundqvist 2014.

- Compare Hultkrantz 1956:211.

- Hávamál st. 109, 111, 164, in Neckel/Kuhn 1983:34, 44.

- Vǫluspá st. 21, in Neckel/Kuhn 1983:5.

- Grímnismál st. 48, in Neckel/Kuhn 1983:67.

- Many researchers into Old Norse religion have emphasized this foremost position of especially the god Þórr, and to some extent Freyr (for example Turville-Petre 1964). It is also indicated in the Scandinavian theophoric place names. Although the name Óðinndoes occur in some place names, it is virtually never found in the names of central places, which instead include gods’ names such as Freyr/Frø, Þórr and Njǫrðr/*Niærdh– (Vikstrand 2001:412–414 with references). In my opinion the most reasonable explanation for this pattern is that the cult of Óðinn, and that of Þórr, Freyr, Freyja and Njǫrðr, above all belonged to two different religious configurations that were related to different social contexts. This is also supported by the fact that the worship of Þórr, Freyr and Freyja, but not Óðinn, played prominent parts in the religion of the Icelanders during the Viking Age. According to Gabriel Turville-Petre (1972) this was because Óðinn was above all revered by a Scandinavian warrior aristocracy, which was not represented among those who immigrated to Iceland.

- Ynglinga saga Ch. 10, in Aðalbjarnarson 1979:25.

- Skírnismál 3, in Neckel/Kuhn 1983:69.

- Lokasenna 35, in Neckel/Kuhn 1983:103.

- Snorri states in Gylfaginning Ch. 23 (Faulkes 1988:23), that Njǫrðr could calm the sea, give good wind for navigation, and was invoked for a good catch when fishing (til veiða). Snorri, however, is the only source of this brief information. Again in Skáldskaparmál Ch. 14 (Faulkes 1998:19), Snorri claims that Ullr was characterized as veiði-áss‘hunting/fishing god’. However, this kenning does not prove that Ullr was invoked by hunters and fishermen. It may just as well be associated with a lost myth, in which Ullr himself went hunting or fishing (Nordberg 2006:406–407). Similarly, the myth that relates Þórr’s fishing expedition and the Midgarðr’s serpent primarily had a cosmologic function, and cannot in my view be regarded as evidence that fishermen generally invoked Þórr for a good catch.

- Cf. Hultkrantz (ed.) 1961a; Honko 1993:63–71,117–189; Sarmela 2009.

- Joensen 1975, 1981; Löfgren 1981; Tillhagen 1985; Hodne 1997.

- In the introduction to the anthology The Supernatural Owners of Nature, Åke Hultkrantz (1961b:7) sententiously summarizes the tradition complex of the Owner: “One of the key conceptions in primitive hunting ideology is precisely the notion of the ‘owner’ of Nature. The owner – or, as he may also be called, the master, lord, ruler, guardian – rules over a certain region or over a certain animal species. As soon as man sets foot upon and exploits this region or hunts these animals, he risks feuding with the owner unless contact with the latter is established before or after the encroachment. This contact finds expression in rites calculated to secure the owner’s permission or to conciliate him for an action already performed. The owner is also frequently the subject of legends and, where he is identified with higher divine beings, as is the case in e.g. South America, also in myths.”

- Cf. Granberg 1935; Gambo 1965; Häll 2013.

- Georges Dumézil (1973:213–230) has suggested that Njǫrðr might be identified with the ruler of the sea (Sw. havsrå and sjörå) in later folk traditions. This hypothesis has not gained support from other scholars, yet we should not rule out the possibility that some of Njǫrðr’s functions may have locally coincided with those of the havsrå and sjörå in communities that were particularly dependent on marine livelihoods.

- Joensen 1975.

- Landnámabók Ch. S329, in Benediktsson 1986:330.

- Possibly, these ethnographic and folkloric analogies may hint at why information about religious traditions linked to hunting and fishing is missing in the earliest sources. These types of traditions were often expressed in folk beliefs, folk legends, and immaterial rit-ualistic behaviours, while the sources on Late Iron Age and Viking Age religion in Scandinavia are mostly of other genres and types, comprising for example written and pictorial mythological material, religious place names, ancient monuments and archaeological finds.

- Honko 1993:51–60.

- Löfgren 1981:80, my translation “… en miljö, där tron på över-naturliga krafter i fisket var en levande realitet och där inlärningen av rituella tekniker och magiska regler ingick som en naturlig del av socialisationen till fiskaryrket”.

- Löfgren 1981:82, my translation “Vår kulturella erfarenhetsvärld kan alltså vara fylld av inre motsättningar och inkonsistenser, och till detta kommer att individer kan växla mellan olika kulturella repertoarer eller värdesystem beroende på den handlingssituation de befinner sig i. Det är denna typ av problem vi mött i den tidigare diskussionen av hur fiskare kunde förvandlas från skeptiker till trosutövare efter en usel fiskesäsong, eller hur Jesus och havsfrun kunde existera sida vid sida i fiskarbefolkningens liv. För de flesta fiskare var säkerligen tron på övernaturliga krafter ett religiöst system som klart avgränsades från den kristna världsbilden. Dessa två kosmologier existerade sida vid sida som autonoma och till stor del motstridiga moralsystem, även om det förekom en viss integration (synkretism) dem emellan.”

- Although cf. e.g. Gunnell 1995; 2011.

- Cf. Andersson 2006.

- At least judging, for instance, by the mythical allusions in West Norse skaldic poetry and the religious iconography from all over Scandinavia.

- Drobin 1968.

- This is, for example, implied by Scandinavia’s theophoric place names, which mainly indicate public cult sites dedicated to Óðinn, Þórr, Freyr, Ullr/Ullinn, Njǫrðr, Týr and probably Freyja. To quote Stefan Brink, the toponymic sources “does not indicate that there was an actual cult of all the gods and goddesses in the pantheon mentioned in Snorra Edda, the Poetic Edda, skaldic poetry, and by Saxo” (Brink 2007:124–125).

- Cf. Gunnell 1995; 2011.

- Compare Olsson 1985; Nordberg 2004:60–65, 121–151.

- Compare for example how the tomte or nisse was portrayed in much different ways in folk legends and folk beliefs in pre-Modern Scandinavia (Ejdestam 1943).

Bibliography

- Adam of Bremen. Schmeidler, Bernhard. 1917. Hamburgische Kirchengeschichte. Scriptores Rerum Germanicarum in usum scholarum ex monumentis germaniae historicis separatim editi. Magistri Adam Bremensis Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum. Hannover: Hahnsche Buchhandlung.

- Andersson, Theodore M. 2006. The Growth of the Medieval Icelandic Sagas (1180–1280). London: Cornell University Press.

- Beck, Inge. 1967. Studien zur Erscheinungsform des heidnischen Opfers nach altnordischen Quellen. München. (Diss).

- Bertell, Maths. 2003. Tor och den nordiska åskan. Föreställningar kring världsaxeln. Stockholm: Stockholms universitet. (Diss).

- Blaney, Benjamin. 1972. The Berserker. His Origin and Development in Old Norse Literature. (Unprinted Diss). University of Colorado: Department of Languages and Literature.

- Brady, Caroline. 1983. Warriors’ in Beowulf. An Analysis of the Nominal Compounds and an Evaluation of the Poet’s Use of Them. In Anglo-Saxon England II, 199–246.

- Brink, Stefan. 1999. Social Order in Early Scandinavian Landscape. In Settlement and Landscape. Proceedings of a Conference in Århus, Denmark, May 4–7 1998. C. Fabech, J. Ringtved (eds.). Høbjerg. Jysk Arkæologisk Selskabs skrifter, 423–439.

- Brink, Stefan. 2007. How Uniform was the Old Norse Religion? In Learning and Understanding in the Old Norse World. Essays in Honour of Margaret Clunies Ross. J. Quinn & K. Heslop & T. Wills (eds.). Turnhout: Brepols Publishers. 105–136.

- Carlie, Anne. 2004. Forntida byggnadskult. Tradition och regionalitet i södra Skandinavien. Stockholm: Riksantikvarieämbetets förlag.

- Drobin, Ulf. 1968. Myth and Epical Motifs in the Loki-Research. In Temenos 3, 19–39.

- DuBois, Thomas. 1999. Nordic Religions in the Viking Age. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Dumézil, Georges. 1973. Njörðr, Nerthus and the Scandinavian Folklore of Sea Spirits. In From Myth to Fiction. The saga of Hadingus. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 213–230.

- Edda. Neckel, Gustav & Kuhn, Hans (eds.). 1983. Edda. Die Lieder des Codex Regius nebst verwandten Denkmälern. 5. verbesserte Auflage. Vol. I. Text. Heidelberg: Carl Winter Universitätsverlag.

- Edda Snorri Sturlusonar. Faulkes, Anthony (ed.). 1988. Snorri Sturluson. Edda. Prologue and Gylfaginning. London: Viking Society for Northern Research

- Ejdestam, Julius. 1943. Är tomten ett dragväsen? In Folkminnen och folktankar 30, 8–17.

- Enright, Michael. 1996. Lady with a Mead Cup. Ritual, Prophecy and Lordship in the European Warband from La Tène to the Viking Age. Portland: Four Courts Press.

- Eskeröd, Albert. 1964. Needs, Interests, Values, and the Supernatural. In Lapponica. Studia Ethnographica Upsaliensia XXI, 81–98.

- Faulkes, Anthony. 1998. Snorri Sturluson. Edda. Skáldskaparmál 1. Introduction, Text and Notes. London: Viking Society for Northern Research.

- Gambo, Ronald. 1965. The Lord of Forest and Mountain Game in the More Recent Folk Traditions of Norway. In Fabula 7:1, 33–52.

- Granberg, Gunnar. 1935. Skogsrået i yngre nordisk folk tradition. Skrifter utg. av Kungl. Gustav Adolfs Akademien för folklivs forskning, 3. Uppsala.

- Gunnell, Terry. 1995. The Origins of Drama in Scandinavia. Cambridge: Brewer.

- Gunnell, Terry. 2011. The Drama of the Poetic Edda. Performance as a Means of Transformation. In Pogranicza teatral nosci. Poetzja, poetyka, praktyka. A. Dąbrówski (ed.). Institut Badán literackich polskiej akademii nauk, 13–40.

- Heimskringla. Bjarni Aðalbjarnarson (ed.). 1979. Heimskringla I. Íslenzk fornrit 26. Reykjavík: Hið íslenzka Fornritafélag.

- Herschend, Frands. 1998. The Idea of the Good in Late Iron Age Society. Uppsala: OPIA 15.

- Hodne, Ørnulf. 1997. Fiske og jakt. Norske folke traditioner. J. W. Cappelens forlag.

- Honko, Lauri. 1993. The Great Bear. A Thematic Anthology of Oral Poetry in the Finno-Ugrian Languages. Helsinki: Suomalaisen kirjallisuuden seura.

- Hultgård, Anders. 2001. Lokalgottheiten. In Reallexikonder germanischen Altertumskunde 18. Berlin & New York: De Gruyter, 476−479.

- Hultgård, Anders. 2003. Ár – ”gutes Jahr und Ernteglück” – ein Motivkomplex in der altnordischen Literatur und sein religions-geschichtlicher Hintergrund. In Runica – Germanica – Mediaevalia. W. Heizmann, A. van Nahl (eds.). Berlin/New York. 282–308.

- Hultgård, Anders. 2007. Wotan-Odin. In Reallexikon der Germanische Altertumskunde 35. Berlin & New York: De Gruyter, 750–785.

- Hultkrantz, Åke. 1956 Configurations of Religious Belief among the Wind River Shoshoni. In Ethnos 1956:3–4, 194–215.

- Hultkrantz, Åke. (ed.) 1961a. The Supernatural Owners of Nature. Nordic Symposium on the Religious Conceptions of Ruling Spirits (genii loci, genii speciei) and allied Concepts. Stockholm Studies in Comparative Religion 1. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell.

- Hultkrantz, Åke. 1961b. Preface. In Hultkrantz 1961a, 7–8.

- Häll, Mikael. 2013. Skogsrået, näcken och djävulen. Erotiska naturväsen och demonisk sexualitet i 1600- och 1700-talens Sverige. Stockholm: Malört.

- Íslendingabók, Landnámabók. Jacob Benediktsson (ed.). 1986. Íslendingabók Landnámabók. Íslenzk fornrit 1. Reykjavík: Hið íslenzka Fornritafélag.

- Joensen, Jóan Pauli. 1975. Færøske sluppfiskere. Etnologisk undersøgelse af en erhvervsgruppes liv. Skrifter från Folklivsarkivet i Lund nr 17. Lund: Liber Läromedel.

- Joensen, Jóan Pauli. 1981. Tradition och miljö i färöiskt fiske. In Tradition och miljö. Ett kulturekologiskt perspektiv. L. Honko & o. Löfgren (eds). Lund: Liber läromedel. 95–134.

- Krístni saga. Guðni Jónsson (ed.). 1968. Íslendinga sögur I. Reykjavík: Íslendingasagnaútgáfan.

- Löfgren, Orvar. 1981 De vidskepliga fångstmännen – magi, ekologi och ekonomi i svenska fiskarmiljöer. In Tradition och miljö. Ett kulturekologiskt perspektiv. L. Honko, O. Löfgren (eds.). Lund: Liber läromedel, 64–94.

- McKinnell, John & Simek, Rudolf & Düwel, Klaus. 2004. Runes, Magic and Religion. A Sourcebook. Studia Medievalia Septentrionalia 10. Wien: Fassbender.

- Murphy, John Luke. 2018. Paganism at Home: Pre-Christian Private Praxis and Household Religion in the Iron-Age North. In Scripta Islandica 2018.

- Nordberg, Andreas. 2004. Krigarna i Odins sal. Dödsföreställningar och krigarkult i fornnordisk religion. Stockholm: Stockholms universitet (Diss. 2003).

- Nordberg, Andreas. 2006 Jul, disting och förkyrklig tideräkning. Kalendrar och kalendariska riter i det förkristna Norden. Acta Academiae Regiae Gustavi Adolphi 91. Uppsala: Swedish Science Press.

- Nordberg, Andreas. 2006. Ull und Ullin. In Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde 31. Berlin & New York: De Gruyter, 406–407.

- Olsson, Tord. 1985. Gudsbildens gestaltning. Litterära kategorier och religiös tro. In Svensk religionshistorisk årsskrift 1, 42–63.

- Olsson, Tord. 2000 De rituella fälten i Gwanyebugu. In Svensk religions historisk årsskrift 9, 9–63.

- Santesson, Lillemor. 1989. En blekings blotinskrift. En nytolkning av inledningsraderna på Stentoftenstenen. In Fornvännen 84, 221–229.

- Sarmela, Matti. 2009. Finnish Folklore Atlas. Ethnic Culture of Finland 2. Helsinki: Matti Sarmela.

- Schjødt, Jens Peter. 2007. Óðinn, Warriors, and Death. In Learning and Understanding in the Old Norse World. Essays in Honour of Margaret Clunies Ross. J. Quinn et al. (eds.). Turnhout: Brepols, 137–152.

- Schjødt, Jens Peter. 2012. Óðinn, Þórr and Freyr. Functions and Relations. In News from the Other World. Studies in Nordic Folklore, Mythology and Culture. In Honor of John F. Lindow. M. Kaplan & T. R. Tangherlini (eds.). Berkley: North Pinehurst Press, 61–91.

- Schulte, Michael. 2006. Ein kritischer Kommentar zum Erkenntnisstand der Blekinger Inschriften. In Zeitschrift für deutsches Altertum und deutsches Literatur 135, 399–412.

- Steinsland, Gro. 2005. Norrøn religion. myter, riter, samfunn. Oslo: Pax forlag A/S.

- Sundqvist, Olof. 2014. Frömer än en fruktbarhetsgud? Saga och sed 2014, 43–67.

- Sundqvist, Olof. 2016. An Arena for Higher Powers. Ceremonial Buildings and Religious Strategies for Rulership in Late Iron Age Scandinavia. Leiden: Brill.

- Sundqvist, Olof & Hultgård, Anders. 2004. The Lycophoric Names of the 6th to 7th Century Blekinge Rune Stones and the Problem of their Ideological Background. In Namenwelten. Ortsund Per-sonennamen in historischer Sicht. Berlin & New York: de Gruyter, 583–602.

- Tambiah, Stanley J. 1970. Buddhism and the Spirit Cults in North-East Thailand. London: Cambridge University Press.

- Tillhagen, Carl-Herman. 1985. Jaktskrock. Stockholm: LTs förlag.

- Turville-Petre, Gabriel. 1964. Myth and Religion of the North. The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

- Turville-Petre, Gabriel. 1972. The Cult of Óðinn in Iceland. In Nine Norse Studies. London: Viking Society for Northern Research, 1–19.

- Vikstrand, Per. 2001. Gudarnas platser. Förkristna sakrala ortnamn i Mälarlandskapen. Acta Academiae Regiae Gustavi Adolphi, 77. Uppsala.

- de Vries, Jan. 1962. Altnordisches Etymologisches Wörterbuch. Leiden: Brill.

- Wessén, Elias. 1924. Studier till Sveriges hedna mytologi och fornhistoria. Uppsala universitets årsskrift 1924. Uppsala: A.-B. Lundequistska bokhandeln.

Contribution (339-370) from Myth, Materiality, and Lived Religion: In Merovingian and Viking Scandinavia, edited by Klas Wikström af Edholm, Peter Jackson Rova, Andreas Nordberg, Olof Sundqvist, and Torun Zachrisson (2019, Stockholm University Press), published by OAPEN under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.