Reasons given throughout our history for protesting the authority of the federal government and perceiving the State as a threat.

Introduction

The United States came into being through a colonial revolt against the British monarchy and, ever since, Americans have remained uneasy about the power of the State, or centralized, national government. From the eighteenth century on, American intellectual and political life has included a strong current of anti-statism, hostility toward centralized authority. The nation’s founding documents lay out a vision of limited, federal power: The Declaration of Independence asserts that government exists in order to ensure the rights that people naturally and inherently possess. A just government depends on “the consent of the governed” and “whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government.” These two claims have been extraordinarily important in shaping American political thought: individual liberty takes precedence over government authority and people have the right to overthrow a government that violates their rights to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

However, anti-statism is, of course, not the only influence within American thought. The Founders could not just reject a government; they also had to create a new one. Initially, under the Articles of Confederation, they designed a very weak national authority and granted each of the 13 states considerable power to independently manage its own affairs. But just five years after the end of the Revolution, a group of citizens called Federalists concluded that this weak national government was a failure. They argued that the country required a stronger federal authority with the power to raise taxes, to regulate interstate commerce, and to conduct relations with foreign countries, among other things. The Federalists supported the ratification of the Constitution, which would establish a stronger central government. Throughout U.S. history, anti-statist currents have regularly come into conflict with demands such as these for the State to play a more active role in managing the nation and its citizens.

The following collection of documents explores conflicts over the exercise of State power at three important junctures in U.S. history: the Revolution and national founding, the Civil War, and World War II. At each of these formative moments in national history, some Americans challenged—while others defended—the authority of the federal government over individual citizens and states. It is important to note that, in these documents, anti-statism does not emerge as a coherent ideology. Rather it includes many different forms of opposition to centralized authority, from reasoned debate to organized rebellion to mob violence. What does emerge is a long and varied history of American anti-statist thought and sentiment.

Resistance to British Government

John Dickinson’s “Liberty Song” is considered America’s first significant political song. It was inspired by the Massachusetts Legislature’s “Circular Letter,” published in February 1768. This letter was written by Samuel Adams to protest the Townshend Acts, laws passed by the British Parliament which taxed colonists for goods such as paper, paint, glass, and tea. The taxes were part of a series of laws, including the Stamp Act and the Sugar Act, designed both to raise revenue and to assert tighter political control over the colonies. When Boston residents resisted paying the taxes, the British government sent troops to occupy the city. The conflict resulted in the Boston Massacre of 1770 and set the stage for the Revolution six years later.

The Debates over the Constitution

During the years 1787 and 1788, Americans hotly debated the merits of the proposed Constitution in newspapers and state legislatures. The essays published under the pseudonym Federal Farmer present some of the more moderate and most influential arguments against the proposed Constitution. Scholars believe the essays were probably written not by a farmer, but by a New York merchant, Melancton Smith, who spoke against the Constitution at New York’s ratification convention. Some Anti-Federalists advocated direct democracy, or the popular participation in government that is only possible when government is local and the population is small, as in rural areas. Others, including Federal Farmer, did not promote populism or agrarianism, but believed in the importance of state legislatures to act as the people’s representatives. Both Anti-Federalist groups expressed concern that the proposed Constitution did not specifically identify the rights held by individuals that the government must respect. They feared that the consolidation of power in the national government would undermine individual liberties and empower a small political elite.

In the excerpt above, Federal Farmer warns of the dangers of a large republic. James Madison famously challenged these arguments in Federalist 10, arguing that only a large republic could limit the power of factions. The September 1789 article included here from New York’s Gazette of the United-States suggests how, even after the Constitution’s ratification, Americans continued to debate its merits and, specifically, to address the issue of the republic’s size and regional differences. The article opens with the quote: “The diversity of interests in the United States, under a wise government, will prove the Cement of the Union.”

The Gazette also presents the first twelve proposed amendments to the Constitution. Ten of these amendments would be ratified by state legislatures over the coming years and would become known as the Bill of Rights. These amendments won over a number of Antifederalists who had previously opposed the Constitution.

Southern Secession

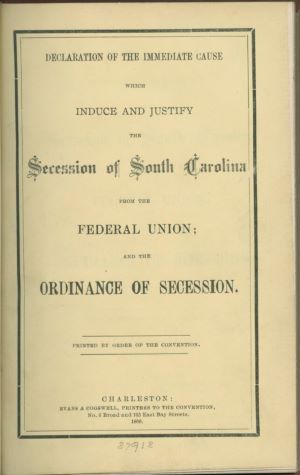

The most profound challenge to the authority of the federal government occurred when Southern states attempted to leave the Union and form an independent country, the Confederate States of America, in the 1860s. Regional tensions had been rising for decades over the question of whether slavery would extend into the new territories west of the Mississippi. Abraham Lincoln’s election as president in the fall of 1860 prompted Southern secessionists to act. Lincoln insisted that he did not intend to interfere with the institution of slavery in the southeastern states where it already existed. However, he was firmly opposed to allowing slavery in the new territories and openly declared his personal belief that slavery was wrong. South Carolina led the movement and declared its secession on December 20, 1860. Six other states joined South Carolina before Lincoln’s inauguration in March 1861. A total of 11 states would eventually attempt to secede.

Declaration of Causes of Secession Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union, 8-9 (1860). / Photos courtesy Internet Archive, Public Domain

The documents in this section include a portrait of the South Carolina Congressional delegation, an excerpt from a pamphlet explaining their decision to secede, and excerpts from Lincoln’s first inaugural address in which he provided his first full public defense of federal authority in the face of the Southern secession.

Anti-Statism in the North

Southern secessionists were not the only Americans to challenge the authority of the federal government during the Civil War. During the first two years of the war, each state had been responsible for recruiting soldiers for its regiments. In March 1863, after a series of losses on the battlefield, Lincoln concluded that the army needed more soldiers. He signed into effect the Union’s first military draft, which required every male citizen between the ages of 20 and 45 to enroll. Men were expected to serve if called, or pay a commutation fee, or hire a substitute. Many poor and working-class men could not afford such payments and resented seeing the wealthy avoid service. These working-class whites also expressed fear of job competition from slaves freed by the Emancipation Proclamation issued earlier that year. Protests erupted in cities and towns throughout the North. T

he most violent occurred in New York City, where mobs, consisting largely of Irish immigrants, rioted for five days. They attacked the provost marshal’s office, where the draft was taking place, then vented much of their rage on the city’s African American community. Over the course of the week, the rioters lynched 11 black men, burned an orphanage for black children, looted and destroyed numerous black-owned businesses, and forced hundreds of African Americans out of the city. The New York–based magazine, Harper’s Weekly, provided extensive coverage of the draft riots, including the illustrations above.

Opposition to U.S. Involvement in World War II

The United States public had been strongly isolationist, or opposed to U.S. involvement in international conflicts, since World War I. The pamphlet and editorial cartoons included here offer powerful expressions of that opposition. The America First Committee was among the most prominent anti-war organizations. It drew support from politicians and others on both the left and the right, though its most visible spokesman was the aviator Charles Lindbergh, a longtime critic of the Roosevelt administration.

The group disbanded after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. The Chicago Tribune cartoonist John T. McCutcheon maintained his opposition throughout the war, as demonstrated by these illustrations.

Supporting the War Effort

As Britain came under assault by Germany, Roosevelt tried to engage the United States in the war and to work around isolationist sentiment by devising the Lend-Lease Act. This law authorized the president to sell, lend, lease, exchange, or transfer war materials to any country whose defense he deemed essential to U.S. interests.

In January 1941, Roosevelt presented his most compelling argument for U.S. involvement in World War II in his “Four Freedoms” speech in which he insisted that American democracy depended upon the survival of democracies in Europe.

These advertisements, which appeared in Life magazine in 1942 and 1944, present unofficial arguments in support of the war effort. They indicate the extent to which private corporations and individuals embraced—or were expected to embrace—the war effort following Pearl Harbor.

Originally published by Newberry Digital Collections for the Classroom, Newberry Library, 06.26.2012, under the terms of a Creative Commons Public Domain license.