Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Coffee culture is the set of traditions and social behaviors that surround the consumption of coffee, particularly as a social lubricant. The term also refers to the cultural diffusion and adoption of coffee as a widely consumed stimulant. In the late 20th century, espresso became an increasingly dominant drink contributing to coffee culture,[1] particularly in the Western world and other urbanized centers around the globe.

The culture surrounding coffee and coffeehouses dates back to 16th century Turkey.[2] Coffeehouses in Western Europe and the Eastern Mediterranean were not only social hubs but also artistic and intellectual centres. Les Deux Magots in Paris, now a popular tourist attraction, was once associated with the intellectuals Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir.[3] In the late 17th and 18th centuries, coffeehouses in London became popular meeting places for artists, writers, and socialites, as well as centres for political and commercial activity. In the 19th century a special coffee house culture developed in Vienna, the Viennese coffee house, which then spread throughout Central Europe.

Elements of modern coffeehouses include slow-paced gourmet service, alternative brewing techniques, and inviting decor.

In the United States, coffee culture is often used to describe the ubiquitous presence of espresso stands and coffee shops in metropolitan areas, along with the spread of massive, international franchises such as Starbucks. Many coffee shops offer access to free wireless internet for customers, encouraging business or personal work at these locations. Coffee culture varies by country, state, and city. For example, the strength of existing café-style coffee culture in Australia explains Starbucks’s negative impact on the continent.[4]

In urban centres around the world, it is not unusual to see several espresso shops and stands within walking distance of one another, or on opposite corners of the same intersection. The term coffee culture is also used in popular business media to describe the deep impact of the market penetration of coffee-serving establishments.[5]

Coffeehouses

A coffeehouse or café is an establishment that primarily serves coffee, as well as other beverages. Historically, cafés have been important social gathering places in Europe, and continue to be venues of social interaction today. During the 16th century, coffeehouses were temporarily banned in Mecca due to a fear that they attracted political uprising.[6]

In 2016, Albania surpassed Spain as the country with the most coffeehouses per capita in the world. In fact, there are 654 coffeehouses per 100,000 inhabitants in Albania; a country with only 2.5 million inhabitants.[7]

Café culture in China has multiplied over the years: Shanghai alone has an estimated 6,500 coffeehouses, including small chains and larger corporations like Starbucks.[8]

In addition to coffee, many cafés also serve tea, sandwiches, pastries, and other light refreshments. Some cafés provide other services, such as wired or wireless internet access (the name, internet café, has carried over to stores that provide internet service without any coffee) for their customers. This has also spread to a type of café known as the LAN Café, which allows users to have access to computers that already have computer games installed.[9]

Social Aspects

Many social aspects of coffee can be seen in the modern-day lifestyle. By absolute volume, the United States is the largest market for coffee, followed by Germany and Japan. Canada, Australia, Sweden and New Zealand are also large coffee-consuming countries. The Nordic countries consume the most coffee per capita, with Finland typically occupying the top spot with a per-capita consumption of 12 kg per year, followed by Norway, Iceland, Denmark, and Sweden.[10][11] Consumption has vastly increased in recent years in the traditionally tea-drinking United Kingdom, but is still below 5 kg per person per year as of 2005. Turkish coffee is popular in Turkey, the Eastern Mediterranean, and southeastern Europe.

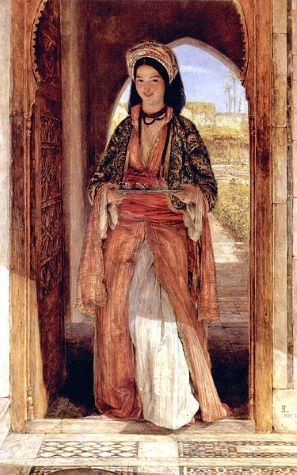

Coffeehouse culture had a strong cultural penetration in much of the former Ottoman Empire, where Turkish coffee remains the dominant style of preparation. The coffee enjoyed in the Ottoman Middle East was produced in Yemen/Ethiopia, despite multiple attempts to ban the substance for its stimulating qualities. By 1600, coffee and coffeehouses were a prominent feature of Ottoman life.[12] There are various scholarly perspectives on the functions of the Ottoman coffeehouse. Many of these argue that Ottoman coffeehouses were centres of important social ritual, making them as, or more important than, the coffee itself.[13]

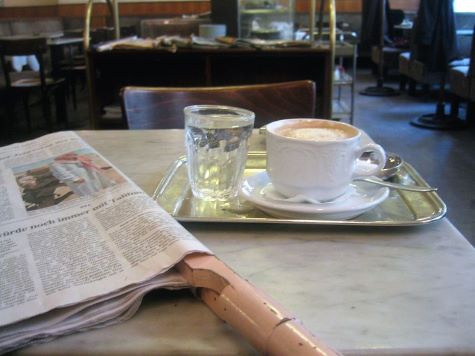

Coffee has been important in Austrian and French culture since the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Vienna’s coffeehouses are prominent in Viennese culture and known internationally, while Paris was instrumental in the development of “café society” in the first half of the 20th century.

The Viennese coffee house culture then spread across Central Europe. Scientists and artists met in the special microcosm of the Viennese coffee houses of the Habsburg Empire. The artists, musicians, intellectuals, bon vivants and their financiers met in the coffee house and discussed new projects, theories and worldviews. A lot of information was also obtained in the coffee house, because local and foreign newspapers were freely available to all guests. This multicultural atmosphere and culture was largely destroyed by the later National Socialism and Communism and only persisted in individual places that remained in the slipstream of history, such as Vienna or Trieste. Trieste in particular was and is an important point of reference in terms of coffee culture, because it is the most important port and processing location for coffee in Central Europe and Italy. In this diverse coffee house culture of the multicultural Habsburg Empire, various types of coffee preparation also developed. This is how the world-famous cappuccino developed from the Viennese Kapuziner coffee via the Italian-speaking parts of the empire in northern Italy.[14]

In France, coffee consumption is also often viewed as a social activity and exists largely within the café culture.[15] Espresso based drinks, including but not limited to café au lait and caffè crema, are most popular within modern French coffee culture.

Notably in Northern Europe, coffee parties are a popular form of entertainment. The host or hostess of the coffee party also serves cake and pastries, which are sometimes homemade. In Germany, Netherlands, Austria, and the Nordic countries, strong black coffee is also regularly consumed during or immediately after main meals such as lunch and dinner and several times a day at work or school. In these countries, especially Germany and Sweden, restaurants and cafés will often provide free refills of black coffee, especially if customers purchase a sweet treat or pastry with their drink. In the United States, coffee shops are typically used as meeting spots for business, and are frequented as dating spots for young adults.

Coffee has played a large role in history and literature because of the effects of the industry on cultures where it is produced and consumed. Coffee is often regarded as one of the primary economic goods used in imperial control of trade. The colonised trade patterns in goods, such as slaves, coffee, and sugar, defined Brazilian trade for centuries. Coffee in culture or trade is a central theme and prominently referenced in poetry, fiction, and regional history.

The Coffee Break

A coffee break is a routine social gathering for a snack or short downtime by employees in various work industries. Allegedly originating in the late 19th century by the wives of Norwegian immigrants, in Stoughton, Wisconsin, it is celebrated there every year with the Stoughton Coffee Break Festival.[16] In 1951, Time Magazine noted that “since the war, the coffee break has been written into union contracts”.[17] The term subsequently became popular through a 1952 ad campaign of the Pan-American Coffee Bureau which urged consumers to “give yourself a Coffee-Break — and Get What Coffee Gives to You.”[18] John B. Watson, a behavioural psychologist who worked with Maxwell House later in his career, helped popularise coffee breaks within American culture.[19]

By Country

Albania

In 2016, Albania surpassed Spain by becoming the country with the most coffeehouses per capita in the world.[20] There are 654 coffeehouses per 100,000 inhabitants in Albania, a country with only 2.5 million inhabitants. This is due to coffeehouses closing down in Spain because of the economic crisis, whereas Albania had an equal amount of cafés opening and closing. Also, the fact that it is one of the easiest ways to make a living after the fall of communism in Albania, together with the country’s Ottoman legacy, further reinforces the strong dominance of the nation’s coffee culture.

Esperantujo

In Esperanto culture, a gufujo (plural gufujoj) is a non-alcoholic, non-smoking, makeshift European-style café that opens in the evening. Esperanto speakers meet at a specified location, either a rented space or someone’s house, and enjoy live music or readings with tea, coffee, pastries, etc. There may be a cash payment required as expected in an actual café. It is a calm atmosphere in direct contrast to the wild parties that other Esperanto speakers might be having elsewhere.

Italy

In Italy, locals drink coffee at the counter, as opposed to taking it to-go. Italians serve espresso as the default coffee, don’t flavor espresso, and traditionally never drink cappuccinos after 11 a.m.[21] In fact, dairy-based espresso drinks are usually only enjoyed in the morning.[22] The oldest cafe in Italy is Caffe Florian in Venice.[23]

In terms of coffee consumption, the city of Trieste is a specialty, because typical people from Trieste drink an average of 1500 cups of coffee a year. That is about twice the amount that is usually drunk in Italy.[24]

Japan

In 1888, the first coffeehouse opened in Japan, known as Kahiichakan. Kahiichakan means a café that provides coffee and tea.[25]

In the 1970s, many kissaten (coffee-tea shop) appeared around the Tokyo area such as Shinjuku, Ginza, and in the popular student areas such as Kanda. These kissaten were centralized in estate areas around railway stations with around 200 stores in Shinjuku alone. Globalization made the coffee chain stores start appearing in the 1980s.[25] In 1982, the All Japan Coffee Association (AJCA) stated that there were 162,000 stores in Japan. The import volume doubled from 1970 to 1980 from 89,456 to 194,294 tons.[26]

Sweden

Swedes have fika (pronounced [ˈfîːka] (listen)), often with pastries,[27] although coffee can be replaced by tea, juice, lemonade, hot chocolate, or squash for children. The tradition has spread throughout Swedish businesses around the world.[28] Fika is a social institution in Sweden and the practice of taking a break with a beverage and snack is widely accepted as central to Swedish life.[29] As a common mid-morning and mid-afternoon practice at workplaces in Sweden, fika may also function partially as an informal meeting between co-workers and management people, and it may even be considered impolite not to join in.[30][31] Fika often takes place in a meeting room or a designated fika room. A sandwich, fruit or a small meal may be called fika as the English concept of afternoon tea.[32]

Hong Kong

In the 1920s, mostly wealthy people or those with higher socioeconomic status could afford to drink coffee whereas ordinary people were rarely able to afford the drink, which was more expensive than traditional beverages.[33]

Yuenyeung (coffee with tea) was invented in Hong Kong in 1936.[34]

Endnotes

- “Coffee culture: A history”. Gourmet Traveller. Retrieved 2019-04-01.

- “The Tradition Of Coffee And Coffeehouses Among Turks”. www.turkishculture.org. Retrieved 2019-04-01.

- Smith, Hazel (2018-03-26). “Deux Cafés, S’il Vous Plaît: Les Deux Magots & Café de Flore in Paris”. France Today. Retrieved 2019-04-01.

- Berg, Chris (2008-08-03). “Memo Starbucks: next time try selling ice to Eskimos”. The Age. Melbourne.

- “Coffee Market Analysis, Share, Size, Value | Outlook (2018-2023)”. www.mordorintelligence.com. Retrieved 2019-04-01.

- Nguyen, Clinton. “The history of coffee shows people have been arguing about the drink for over 500 years”. Business Insider. Retrieved 2019-06-27.

- “Rekordi, Shqipëria kalon e para në botë për numrin e lartë të bar-kafeve për banor -“. 19 February 2018.

- Jourdan, Adam; Baertlein, Lisa. “China’s budding coffee culture propels Starbucks, attracts rivals”. Reuters. Reuters. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- Jourdan, Adam; D’Anastasio, Cecilia. “The LAN Cafe Is Making A Comeback”. Reuters. Reuters. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- “Coffee Consumption Per Capita Worldwide”. IndexMundi Blog. Retrieved 2010-05-13.

- “International Coffee Organization – Historical Data”. Ico.org. Retrieved 2011-10-09.

- Baram, Uzi (1999). “Clay tobacco pipes and coffee cup sherds in the archaeology of the Middle East: Artifacts of social tensions from the Ottoman past”. International Journal of Historical Archaeology. 3 (3): 137–151. doi:10.1023/A:1021905918886.

- Mikhail, Alan (2014). The heart’s desire: Gender, urban space, and the Ottoman coffee house. Ottoman Tulips, Ottoman Coffee: Leisure and Lifestyle in the Eighteenth Century ed. Dana Sajdi. London: Tauris Academic Studies. pp. 133–170.

- Helmut Luther “Warum Kaffeetrinken in Triest anspruchsvoll ist” In: Die Welt, 16 February 2015.

- Daniel (2012-05-12). “The café culture in France”. Café de Flore. Retrieved 2019-03-10.

- “Stoughton, WI – Where the Coffee Break Originated”. www.stoughtonwi.com. Stoughton, Wisconsin Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on 2009-05-20. Retrieved 2009-06-11.

Mr Osmund Gunderson decided to ask the Norwegian wives, who lived just up the hill from his warehouse, if they would come and help him sort the tobacco. The women agreed, as long as they could have a break in the morning and another in the afternoon, to go home and tend to their chores. Of course, this also meant they were free to have a cup of coffee from the pot that was always hot on the stove. Mr Gunderson agreed, and with this simple habit, the coffee break was born.

- “MANNERS & MORALS: The Coffee Hour”. Time. Vol. LVII no. 10. March 5, 1951. Retrieved 2019-08-10.

- “The Coffee break”. npr.org. 2002-12-02. Archived from the original on 2009-05-28. Retrieved 2009-06-10.

Wherever the coffee break originated, Stamberg says, it may not actually have been called a coffee break until 1952. That year, a Pan-American Coffee Bureau ad campaign urged consumers, ‘Give yourself a Coffee-Break — and Get What Coffee Gives to You.’

- Hunt, Morton M. (1993). The story of psychology (1st ed.). New York: Doubleday. p. 260.

[work] for Maxwell House that helped make the ‘coffee break’ an American custom in offices, factories, and homes.

- “Albania ranked first in the World for the number of Bars and Restaurants per inhabitant”.

- Santoro, Paola (22 April 2016). “Your Cheat Sheet To Italian Coffee Culture”. Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 27 June 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- “Why You Shouldn’t Even Think About Ordering An Afternoon Latte In Italy”. HuffPost. 2017-08-08. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- “Italy’s Coffee Culture Brims With Rituals And Mysterious Rules”. NPR.org. Retrieved 2020-06-13.

- Gisela Hopfmüller, Franz Hlavac “Triest: Die Kaffeehauptstadt” In: Falstaff, 28 June 2020.

- White, Merry (2012). Coffee Life in Japan. University of California Press; First edition (May 1, 2012).

- “Coffee Market in Japan” (PDF). All Japan Coffee Association (AJCA). July 2012.

- Henderson, Helene (2005). The Swedish Table. U of Minnesota P. p. xxiii-xxv

- Hotson, Elizabeth. “Is this the sweet secret to Swedish success?”. BBC. Retrieved 2017-02-02.

- “Fika |sweden.se”. sweden.se. 2014-05-08. Retrieved 2016-05-21.

- Paulsen, Roland (2014) Empty Labor: Idleness and Workplace Resistance. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge; p. 90 [1]

- Goldstein, Darra; Merkle, Kathrin (2005). Culinary cultures of Europe: identity, diversity and dialogue. Council of Europe. pp. 428–29.

- Johansson Robinowitz, Christina; Lisa Werner Carr (2001). Modern-day Vikings: a practical guide to interacting with the Swedes. Intercultural Press. p. 149.

- coffeeDeAmour (2015-10-28). “【香港歷史】 八十六年老字號 榮陽咖啡”. 香港咖啡文化促進會. Retrieved 2019-03-03.

- Observer staff (October 2006). “New York World 66”.

Originally published by Wikipedia, 10.30.2006, under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.