By Bonnie Calhoun, J.D.

Judicial Clerk

Honorable Stephen K. Bushong

Abstract

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the London coffeehouse and the Parisian salon functioned as what Jürgen Habermas has identified as the public sphere: a place for social interaction outside the private sphere (the home) and the sphere of public authority (the state/court). Although there were many other public sphere institutions—in the form of clubs, theaters, Masonic lodges and the like—coffeehouses were the most important public sphere institutions in London and the same was true for the salons of Paris. Three key characteristics were shared by the coffeehouses and salons as public sphere institutions: sociability, equality and communication. Within the realm of the coffeehouse and salon, a heterogeneous group of people came together to engage in rational debate without regard to rank. Although they shared these three public sphere characteristics, coffeehouses and salons had two important differences. The first is that women were not participants in coffeehouse life, whereas they were the creators and leaders of the salon. Second, coffeehouses were public businesses, open to any man who could afford the penny for coffee. Salons, meanwhile, were firmly in the hands of the salonnières (hostesses), who had the power to choose the guests and deny entry to whomever they saw fit. Through a comparative study of the coffeehouses and salons a better understanding of the public sphere in general and these two institutions in particular can be gained.

Introduction

When the first coffeehouse opened in London in the early 1650s, it was nothing more than a stall in an alley, selling a bitter-tasting exotic drink from the Levant. However, the owner soon found his business lucrative enough to move into a nearby house and from then on coffeehouses began springing up like mushrooms in London, with one pamphleteer proclaiming in 1673 that “the dull Planet Saturn has not finished one Revolution through his Orb [which takes 29 years] since Coffee-houses were first known amongst us, yet ‘tis worth our wonder to observe how numerous they are already grown.”[1] During the coffeehouses’ peak in the eighteenth-century, estimates put their number as high as 2-3,000 in London, although the true number is likely closer to around 500, which is still quite significant for its time.[2]

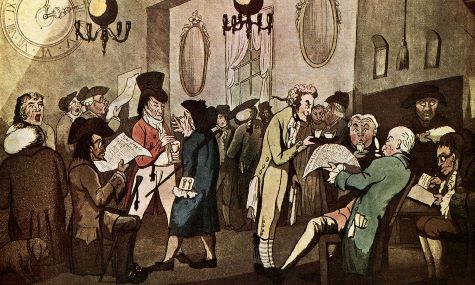

It was not for the taste of coffee that people flocked to these establishments. Indeed, one irate pamphleteer defined coffee, which was at this time without cream or sugar and usually watered down, as “puddle-water, and so ugly in colour and tast [sic].”[3] It was, in fact, the nature of the institution itself that caused its popularity to skyrocket during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. For coffeehouses were not just businesses that dispensed coffee, but were also meeting places, discussion forums, news centers, institutions of literary criticism, auction houses and, in some cases, stock markets, insurance company offices and post boxes. The coffeehouses’ many functions served as what Jürgen Habermas has identified as the public sphere: a place for social interaction outside the court and home. In the public sphere of the coffeehouse, patrons were able to find a space that encouraged sociability, equality and communication. Although the reality of the coffeehouses did not always match the ideal of genteel sociability and true equality was not possible in a hierarchical society, the image of the coffeehouse, as expressed through contemporary pamphlets and newspapers, was one where men were encouraged to engage in both verbal and written discourse with regard for wit over rank. Through this free exchange of ideas, expressed in the coffeehouses and spread throughout society by newspapers and discourse, public opinion was formed. Of course, coffeehouses were not the sole pillars of the public sphere. Many places were emerging that served as a space between the court and the home, but in Britain it was the coffeehouses that made the largest impact.

Across the Channel, France, too, was witnessing the emergence of an Enlightenment public sphere. Like in Britain, theaters, cafés and co-fraternities were spaces where the public sphere was taking shape. However, in France it was the Parisian salons, not the cafés, which were the closest parallel to the British coffeehouse. Although there had been small social gatherings earlier, the salons truly began with the establishment of Madame Rambouillet’s salon, known as “le Chambre Bleu” (the Blue Room), in 1618.[4] This salon, created as an escape from the shallow and rigid court life, was dedicated to refined entertainment such as singing, reciting, and, of course, talking. In order to create an enjoyable and social atmosphere, the salon welcomed men and women possessing great lineage or great wit. Madame Rambouillet’s model was quickly copied and she was followed by a line of great hostesses that held increasingly serious and intellectual salons.

This paper explores how these two institutions—the coffeehouse and the salon—differently expressed the three principles of the public sphere: sociability, equality and communication. Although both salons and coffeehouses had these characteristics, key differences were in place. Coffeehouses were public businesses, open to any man who could afford a cup of coffee. Salons, on the other hand, were private affairs, with doors closed to anyone that the hostess did not want to enter. This led to salons being more egalitarian in one sense, as women played an important role while they were nonexistent as patrons in coffeehouses, but also caused attendance to be more restricted, as participation required an invitation. After explaining the historiography, this paper will look at the place of women in coffeehouses and salons, since their role created an important difference in how these two institutions functioned. It will then progress to exploring the way the three public sphere characteristics of sociability, egalitarianism and communication—both spoken and written—were expressed. Afterwards, the importance and uniqueness of coffeehouses and salons will be shown by describing their less prominent counterparts: Parisian cafés and London bluestocking gatherings. Through exploring the important similarities and differences between the coffeehouses and the salons a better understanding of the public sphere in general and these two institutions in particular can be gained.

Historiography

Interestingly, early historiography of coffeehouses and salons had two different trajectories: coffeehouses were often portrayed as another step on Britain’s triumphant progress toward liberty while salons were regulated to the status of frivolous gatherings. The initial interpretation of coffeehouses was in the Whig school of thought, which sees British history as an inevitable march toward constitutional monarchy. This view of the coffeehouses began while they were still in their golden age, with the popular newspapers The Tatler (1709-1711) and The Spectator (1711-1712), written by diehard Whigs Joseph Addison and Richard Steele. In their papers, Addison and Steele sought to portray the coffeehouses as being home to the genteel values that they wished to share with their readers. It was their depiction of coffeehouses as sociable, egalitarian and full of rational discussion that helped to influence the later Whig historical works such as Thomas Macaulay’s History of England from the Accession of James the Second (1849). In this book, Macaulay reveals the continued Whig interpretation of coffeehouses as representatives of “those core values of gentility, politeness and civility.”[5]

Meanwhile, the historian’s view of salons was often unfairly colored by Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s unflattering portrait, which depicted salon women as a distraction to serious discussion. Even books providing complimentary portrayals of salon women did little to expel this myth. Louis Battifol’s The Great Literary Salons (XVII and XVIII Centuries) (1930) is typical of earlier works on salons. Battifol’s book is filled primarily with character descriptions and anecdotes instead of analysis, and describes the women as charming and witty, but not intelligent, explaining that “to direct a salon successfully it is necessary that a woman be profoundly ignorant.”[6]

An influential new interpretation of the impact of salons and coffeehouses was the publication of Jürgen Habermas Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere. It first appeared in Germany in 1962, but only really began to be influential after it was translated into French in 1978 and then into English in 1989.[7] Habermas argues that during the eighteenth century a bourgeois public sphere was created, separate from the sphere of private life and the sphere of public authority. He identifies three institutions that embodied the idea of the public sphere: English coffeehouses, French salons and German dining societies. Each of these institutions had a number of criteria in common: they were non-hierarchical, inclusive and forums of free and rational debate.[8] Habermas has come under some criticism since publication of his work. Markman Ellis, for example, has convincingly argued that Habermas’ view of the coffeehouse comes from the biased Whig tradition. Joan Landes, meanwhile, critiques Habermas from a feminist perspective, decrying the public sphere as essentially masculine. However, Landes in turn has been accused of misinterpreting Habermas. Dena Goodman, in her article “Public Sphere and Private Life,” shows how Landes groups together court women (who she places in Habermas’ absolutist public sphere) and salon women (who she places in the “authentic” bourgeois public sphere).[9] However, Habermas’ idea seems to have weathered all criticism fairly well and still remains highly influential in the study of both salons and coffeehouses.

The notion of the Habermasian public sphere has been used in two recent interpretations of English coffeehouses: Brian Cowan’s The Social Life of Coffee: The Emergence of the British Coffeehouse (2005) and Markman Ellis’ The Coffee House: A Cultural History (2004). Both show the sociability, equality and communication aspects of the coffeehouses and their importance in British society without getting bogged down in the Whig school of thought. Cowan declares himself a post-revisionist, who rejects the Whiggish teleological view by showing that the acceptance of coffee drinking was not a foregone conclusion but instead became socially legitimate through the new virtuoso culture of curiosity and an increasingly commercial world.[10]

Salons have also been increasingly scrutinized in recent years. Whereas earlier histories were largely descriptive and de-emphasized the serious side of salons, recent authors provide a more analytical view that places serious Enlightenment thought back into the center of salons. Dena Goodman’s important study, The Republic of Letters (1994), in particular put salons in the center of Enlightenment thinking. Benedetta Carveri’s The Age of Conversation (2005), meanwhile, emphasizes the polite aspects of salons and suggests that it is the politesse in the salons that allowed them to be egalitarian.

In general, there have been few works besides Habermas who have seriously studied both coffeehouses and salons. Authors generally focus on either coffeehouses or salons, with only brief mention, if any, of the other’s existence. James Van Horn Melton’s book, The Rise of the Public in Enlightenment Europe (2001), does cover both in his investigation of the public sphere in England, France and the German-speaking territories. However, Melton does not directly compare the two. Instead, he explores coffeehouses and salons separately in depth and explains their importance in each of the three territories he covers.

This paper seeks to remedy the lack of direct comparison of coffeehouses and salon. Through a comparison of both these institutions, a better understanding of the public sphere and the different possible interpretations of the public sphere’s aspects is possible.

Women in the Public Sphere

One of the most striking differences between the coffeehouses and the salons was the role of women. While women had a very central role in salons, in coffeehouses they were relegated to mainly being employees or owners—who, like innkeepers, worked within their establishments. The prominent position of women in the salons and their relative absence in coffeehouses led to these two places having very different atmospheres. In the salons the influence of women led to a more controlled environment while the absence of feminine influence in the coffeehouses led to more free-wheeling debates that some commentators wished were a little more polite and sophisticated.

In the salons the leader was the female hostess, the salonnière. Her role has been described as that of a “governor” and a “civilizer,”[11] but also that of a “tyrant”[12] and a regent of an “absolute monarchy.”[13] She represented order: it was her duty to maintain the civility of the salon. It was she who chose the guests and made sure they were compatible, it was she who guided the conversation so that it would remain within the bounds of sociabilité and politesse, avoiding or ending heated debates, and it was she who politely stopped overly garrulous guests. A woman who was a salonnière understood the importance of her station and took her duty seriously. The dedication of the salonnières can be seen in their ensuring that they remained at home to host guests during regular hours year after year. The great salonnière Julie Lespinasse, for example, received every day from five to nine at night for twelve years, with hardly a vacation.[14]

Women had little effect on coffeehouse life. While women owners or workers were not uncommon in the coffeehouses, any references to women as patrons are few and far between. Many of the references that do exist might be describing prostitutes, who were known to frequent lower-class coffeehouses. A sign that respectable women did not frequent coffeehouses is seen in the July 3, 1713 issue of Addison’s newspaper The Guardian. In it he describes the Lion’s Head he placed in Button’s Coffeehouse in which readers could submit letters to be printed in the newspaper. Looking for letters from a wider audience, Addison wrote that “as I have here a Lion’s Head for the Men, I shall erect an Unicorn’s Head for the Ladies” in a fashionable shop.[15] This statement implies that Addison did not expect women to be in a coffeehouse like Button’s and that his letter box should be in a place more often frequented by the fairer sex. Furthermore, in his A Journey Through England (1714), John Macky, after discussing coffeehouses, added that “if you like rather the Company of Ladies, there are Assemblies at most People of Qualitie’s Houses,”[16] which again indicates that coffeehouses were not places where ladies, at least respectable ones, gathered.

The women who did frequent the coffeehouses as employees and employers had a rather tarnished reputation, with contemporaries often unfairly painting them as having loose morals. This reputation was not helped by women in coffeehouses who did indeed less than virtuous, such as the infamous coffeehouse keeper Moll King who had prostitutes working in her coffeehouse. In a 1747 biography written about her, the author noted that “every Swain, even from the Star and Garter [noble chivalric orders] to the Coffee-House Boy, might be sure of finding a Nymph in waiting at Moll’s Fair Reception House, as she was pleas’d to term it.”[17] Overall, it appears that women in coffeehouses were solely relegated to the role of workers, respectable or otherwise. Respectable women did not patronize coffeehouses and they most certainly did not have as central a role as the salonnières.

Sociability

Perhaps the most important feature of the coffeehouses and salons as members of the Enlightenment public sphere was the opportunity for different social classes to gather in a neutral location. The surprising degree of social mixing in coffeehouses was remarked upon again and again by contemporaries. In his Sunday Ramble, the author describes going to “one of the principal coffee-houses near the Royal Exchange” where “we found the room tolerably full of various kinds of people” who were “promiscuously seated together.”[18] Houghton also noted the phenomenon, remarking that “coffee-houses make all sorts of people sociable, the rich and the poor meet together, as also do the learned and unlearned.”[19] A 1665 pamphleteer observed that “as from th’ top of Pauls high steeple/Th’ whole City’s view’d, even so all people/May here be seen,” and went on to describe urban types of different social classes and even of different nationalities who did not normally associate with each other. Some were from the lower classes, such as “a Player [actor],” an “Aprentice boy,” “a bold Mechanick [manual laborer]” and “a Country Clown.” Men of middle ranks were represented in the form of the “Virtuoso [learned person, scholar],” and the “griping Usurer,” and even those of higher ranks appeared, such as a “gallant” and a “Knight.” Foreigners such as “a Spanish Don [gentleman],” “a brisk Monsieur,” and “a Dutchman” were also present in the coffeehouse.[20]

It was possible for so many different types of people to enter coffeehouses because they were places of business where anyone who could afford to pay the penny for a cup of coffee could enter—even those one would rather not associate with. However, as the years passed there did develop some self-segregation as certain coffeehouses gained reputations for being the home of particular sorts of men. Macky, in his visit to London, noticed this phenomenon and wrote that “the Scots go generally to the British and a Mixture of all Sorts go to the Smyrna…Young Man’s for Officers, Old-Man’s for Stock-Jobbers, Pay-masters and Courtiers, and Little Man’s for Sharpers.”[21] Similarily, “the Parties have their different Places, where however a Stranger is always well received; but a Whig will no more go to the Cocoa-Tree or Ozinda’s, than a Tory will be seen at the Coffee-House of St. James’s.”[22] This gathering of groups usually followed a logical geographical pattern: Nando’s and the Grecian, which were situated near the Inns of Court, were home to those in the legal profession, while clergy often went to Child’s due to its proximity to St. Paul’s Cathedral. Likewise, Jonathon’s and Garraway’s were in the important commercial center of Exchange Alley and catered to merchants, insurance agents, and brokers.[23]

However, no coffeehouse was exclusive to a particular group and the ability to go to different coffeehouses throughout the day allowed an expansion of the social network. In the first issue of the newspaper The Spectator the narrator, Mr. Spectator, talks of freely going to a wide variety of coffeehouses. He writes:

sometimes I am seen thrusting my Head into a Round of Politicians at Will’s, and listening with great Attention to the Narratives that are made…Sometimes I smoak a Pipe at Child’s; and whilst I seem attentive to nothing but the Post-Man, overhear the Conversation of every Table in the Room.”[24]

Furthermore, the clientele of a coffeehouse tended to shift throughout the day, with different times bringing in waves of different groups. This is well illustrated by The Spectator no. 49, when Mr. Spectator goes to his favorite coffeehouse. He describes how “Men differ rather in the time of Day in which they make a Figure than in any real Greatness above one another.”[25] First, “from Six ‘till within a Quarter of Eight” the coffeehouse is filled by Mr. Beaver, a haberdasher and newsmonger, and his group, who are replaced by “Students of the House”—law students—since the coffeehouse is “near one of the Inns of Court.”[26] These young men, who Mr. Spectator thinks, “rise early for no other purpose but to publish their Laziness” at the coffeehouses near the Inns of Court, eventually “give Place to Men who have Business or good Sense in their Faces, and come to the Coffee-house either to transact Affairs or enjoy Conversation.”[27] Thus, in the space of a day at least three different groups dominate one coffeehouse. A man who stayed the entire day, such as Mr. Spectator, could be exposed to a diverse array of people, all for the price of a penny.

Like in the coffeehouses, a remarkable mixture of social classes could be seen om the salons: aristocrats, distinguished foreigners, literati, scientists, abbés, philosophes and, mostly importantly, women. The wide variety of people who attended Mademoiselle Lespinasse’s salon was typical of the salon milieu. There one could find “ministers, diplomats, cardinals, highly placed civil servants, society ladies, famous writers, and young intellectuals starting out in life.”[28] Madame Geoffrin further added to the social array of the salon by adding artists as her guests.

At the salons the salonnière chose her guests and thereby determined the ultimate composition of the room. Guests were there by the grace of the salonnière and usually needed a letter of introduction to be allowed in.[29] Once in, they could still be evicted if the salonnière decided that they were no longer beneficial to her salon. For example, Madame Geoffrin was not afraid to enforce her policy of keeping out querulous guests: the great philosophe Diderot stopped being received in her salon because she felt that his conversation was “quite beyond control.”[30] In general, the salonnières “carefully selected” the company, regulated its numbers and formed the group into a “homogenous unity.”[31]

The decision of who to allow in and who to keep out helped to determine the atmosphere of the salon. Madame du Deffand’s salon, for example, became one of the old aristocracy after her falling out with the philosophe d’Alembert when she “closed her door with contempt to the philosophes, to their jargon and to their ideas.”[32] She had very high expectations, with intelligence not being the sole criteria: “it was imperative that her standard be reached in every particular, and elegant manners, gaiety, and good sense were necessary qualifications.” A brilliant man like Grimm, welcomed in other salons, failed to meet her high standards, and therefore she “never would receive him at all.”[33] Mademoiselle Lespinasse’s salon, on the other hand, was very much a salon of the philosophes; they “were the law; to be admitted, the gens du monde had to be converted to their gospel.”[34] Over time, each salon became distinguished by “its own structure and individual cultural and political orientation”[35] and “every salon had to have its own character, its own style, and its own particular chemistry in the mixture of guests.”[36] This orientation and style was based on the decisions of the salonnière. While men could decide whether or not they attended a salon, it was the salonnière who determined whether they would be invited in at all.

Egalitarianism

While inside the walls of the salon or the coffeehouse, the different social classes were treated with a surprising degree of equality. Although they existed in hierarchical societies, in salons and coffeehouses those with high status and those with only wit to recommend them could rub shoulders, and it was their wit and intelligence, not social rank, which “was supposed to determine who won and who lost in debate.”[37]

The important thing about the coffeehouses is that they not only included so many different groups of people, but that they also provided an area where they could mingle freely, for “here is no respect of persons. Boldly therefore let any person, who comes to drink Coffee sit down in the very Chair, for here a Seat is to be given to no man.”[38] A set of “rules” for the coffeehouse even went as far as to explicitly state the egalitarianism of the coffeehouse in its open seating policy:

First, Gentry, Tradesmen, all are welcome hither,

And may without Affront sit down Together:

Pre-eminence of Place none here should Mind,

But take the next fit Seat that he can find:

Nor need any, if Finer Persons come,

Rise up for to assign to them his Room.[39]

While this was likely not actually from a set of rules posted in the coffeehouse, it does give an idea of the policies found therein, where patrons were expected and perhaps even encouraged to lay aside social differences and simply engage each other. This idea of egalitarianism was quite different from society in general, as one 1661 pamphlet noted: “that great privilege of equality is only peculiar to the Golden Age, and to a Coffee-house.”[40] Indeed, as one anonymous satirist wrote in his The Character of a Coffee-House (1673):

Each man seems a Leveller, and ranks and files himself as he lifts, without regard to degrees or order; so that oft you may see a silly Fop, and a worshipful Justice, a griping Rook [con artist], and a grave Citizen, a worthy Lawyer, and an errant Pickpocket…all blended together; to compose an Oglio [mishmash] of Impertinence.[41]

This type of public gathering space open to anyone who could afford the penny for coffee was a new phenomenon in England. Anyone was allowed to converse with anyone else, and ideas of rank were, temporarily at least, put aside.

Although salonnières were the ones who chose their guests, which could limit the social spectrum more than the leaderless coffeehouses, they also ensured that guests remained on an equal footing and could forget their differences within the walls of the salon. The salon was “a melting-pot which blurred distinctions of birth and profession.”[42] Aristocrats and men of letters mixed freely together in an environment where wit was more important than rank. Here “the aristocracy of genius was brought close to the aristocracy of birth.”[43] In the salons “social differences were ignored and all the players were considered equal.”[44] This mixing was beneficial to all ranks, as the philosophe d’Alembert noted, “the learned brought knowledge and enlightenment; the others brought those good manners and that urbanity which even the worthy need to acquire…Men of the world left her house more cultivated and men of letters more amiable.”[45] According to the playwright Pierre de Marivaux, at Madame de Tencin’s, “there was no question of rank or condition…no one considered their own importance or lack of it.”[46] Some even went so far as to suggest that rank without esprit (wit) was not suitable for a salon guest. One contemporary wrote that

I have seen so many fools of good

house, and those fools so

disagreeable that I would prefer

the conversation of a barbarian or

a parrot…If a person of condition

does not have esprit, let us leave

him in his stable and in his farm,

and let us choose a routurier who

speaks and reasons; we are not in

conversation to spout our

geneaology and to make proofs of

our quarters [of nobility].[47]

The salon women themselves could also prove the emphasis of wit over rank found in the salons. Mademoiselle Lespinasse was a testament to this, a “poor, solitary, less than beautiful woman, with no family support and no social status” who “by virtue of her intellect alone” managed to create one of the most brilliant salons of her time.[48] Madame Geoffrin was also a woman of a non-aristocratic background—her father had been a valet of the wardrobe—who, “everybody is agreed,” came from an origin “entirely obscure and bourgeoise.”[49] Through her salon, she received some of the most brilliant and distinguished men of her time, began a correspondence with Catherine the Great of Russia and was warmly received by the King of Poland, who had been a visitor to her salon.[50]

In reality, although both coffeehouses and salons maintained an aura of social equality, this “much vaunted egalitarianism is an enabling fiction.”[51] Coffeehouses and salons were still a product of their times and an era of true egalitarianism was centuries away. One example of this is the case of Vincent Voiture, the son of a wine merchant and, due to his sharp wit, the toast of Madame de Rambouillet’s salon. Despite his cleverness and his wide admiration in the salons, he was not considered equal to the nobility outside its walls. Another French intellectual of humble birth, Voltaire, the son of a notary, was caught in a similar situation. Within the salon he was considered an equal; outside of it his lower class was distinctly felt. After an argument with the Chevalier de Rohan, the knight refused a duel with Voltaire and instead had his footmen beat the philosopher.[52]

Macky noted that in coffeehouses you “will see Blue and Green Ribbons and Stars, sitting familiarly, and talking with the same freedom, as if they had left their Quality and Degrees of Distance at Home.”[53] These ribbons designated the wearers as belonging to the Order of the Garter (the blue) and the Order of the Thistle (the green), the highest orders of the land which could only be bestowed by the monarch. While Macky describes these men as assembling freely with other coffeehouse patrons, the fact that they continued to wear signs that reflected their rank hinted at the social distinctions that those within the coffeehouses tried to gloss over. The sociability of the salons and coffeehouses could mask the inequalities, but French and British societies were still hierarchical ones based on birth and wealth. Although class remained present in coffeehouses and salons it was largely ignored—a fact that supporters trumpeted and detractors mocked. While a trader would never be considered the equal of a duke, the coffeehouses and salons provided a place where, for a time, the trader could mix with the duke and both be judged not by their station but by their intellect. For the time period, this was a great innovation.

Communication: Rational Debate

An important aspect of coffeehouses and salons as institutions of the public sphere was the ability of participants to engage in rational discourse. Judgment could be passed on a wide variety of subjects, although conversation in salons tended to be more restricted than the freewheeling coffeehouses. The coffeehouse, in fact, became rather notorious for their freedom of conversation. One 1665 pamphlet proclaimed: “It reason seems that liberty/Of speech and words should be allow’d/Where men of differing judgements croud,/And that’s a Coffee-house, for where/Should men discourse so free as there?”[54] Not everyone was pleased with this aspect of the coffeehouses, however. The government and some contemporaries felt that people outside the court had no business discussing affairs of state and that doing so was potentially dangerous. Those who objected to free discourse thought that subjects such as politics were the prerogative of the crown and that open discussion on news would surely lead to sedition. One pamphlet scoffed at the town-wit who plagued the coffeehouses and “whatever is sacred or serious, he seeks to render Ridiculous, and thinks Government and Religion fit objects for his idle and fantastick Buffoonery;”[55] indeed, “every little Fellow in a Chamlet-Cloak takes upon him to transpose Affairs both in Church and State, to shew reasons against Acts of Parliament, and condemn the Decrees of General Councels.”[56] Critics often accused the coffeehouses of spreading rumors and false news:

And all that’s done, though far remote, appears, and in close whispers penetrates our ears…Hither the idle vulgar come and go, carrying a thousand Rumours to and fro; with stale reports some listening ears do fill, some coyn fresh tales, in words that vary still; lies mixt with Truth, all in the telling grows, and each Relator adds to what he knows: here dwells rash error, light credulity, sad panick fears, joys built-on vanity; new rais’d sedition, secret whisperings, of unknown Authors, and of doubtful things: all acts of Heav’n and Earth it boldly views, and through the spacious World enquires for News.[57]

Those in the government made some efforts to suppress and monitor the conversation. Spies could be found in both coffeehouses and salons and King Charles II of England, feeling threatened by the free speech in the coffeehouses, even attempted to shut down the coffeehouses in 1675. His failure is seen by Whiggish historians as a triumph of liberty.[58]

In the salons, the presence of a hostess created a more ordered, controlled environment, with both guests and conversation subject to the salonnière’s discretion. In general, a wide array of topics were covered in the salon with relative freedom, including art, science, foreign cultures, and education. Salons were home to intellectual activity and both the salonnière and her guests enjoyed the ability to discuss a diverse array of subjects. However, the salonnière could decide that certain topics should not be pursued, either because they were deemed too boring and uninteresting, or because they were deemed too dangerous, such as religion and politics.[59] The degree of freedom available in a salon rested entirely in the hands of the salonnière.

Some of the salons were very lightly controlled, such as those of Madame de Tencin and Mademoiselle Lespinasse. These two were very much the home of liberal Enlightenment thought; even such potentially divisive topics as religion and politics were discussed. Madame de Tencin in particular was known for having one of the more liberal salons, with great freedom of conversation, including permitting guests to speak of the royal family in terms that were not always friendly.[60] Other salonnières, such as Madame Geoffrin and Madame de Rambouillet, were more restrictive in their choice of topics. Although Geoffrin enjoyed hosting intellectuals and philosophes in her salon, she did not permit them to go too far. In her salon “the tone remained relatively restrained, with the hostess forbidding any impassioned polemics.”[61] She particularly disliked politics, since it often led to arguments that turned quarrelsome. She “would not allow political discussion in her house”[62] and ensured that “anything that might be subversive or disrespectful of institutions was censured.”[63] If a conversation wandered into dangerous territory or simply became too uninteresting, Geoffrin would put an end to the discussion with her famous simple phrase “Voilà qui est bien” (That’s enough).[64] Madame Rambouillet, another salonnière that kept a tight control over her salon, even went so far as to restrict certain types of language that she did not deem appropriate for salon conversation. She “would not tolerate the use of certain words,” such as “archaic expressions,” “queer provincial locutions,” and “obscure technical terms.”[65] While at first it appears that this censorship was arbitrary, it is likely that both Rambouillet’s control of language and Geoffrin’s control of subject matter were a result of the salonnière trying to maintain the ideals of sociabilité and politesse. The type of language that Rambouillet discouraged was esoteric and obscure and would prevent those who did not understand a word to be unable to contribute to the conversation. Wanting to include everyone, Rambouillet outlawed the language that would be exclusive. Similarly, Geoffrin desired a salon that did not touch on potentially explosive subjects that could lead to anger and disharmony.

Salon guests, for the most part, appreciated the work that the salonnières undertook to retain an intellectual but also harmonious atmosphere. They were often amazed by how well the salonnières could direct their guests, guiding conversation without being overbearing. Marmontel, writing about Mademoiselle Lespinasse, noted that “I could say that she played this instrument with an art that resembled genius; she seemed to know which sound the string she had touched would make; I would say that she knew our minds with our characters so well that, to put them in play, she had only to say a word.”[66] Salonnières were so accomplished and so subtle that often guests did not fully appreciate their work until it made its absence known. Madame Necker wrote to the philosophe Grimm, in the wake of Lespinasse’s death, that d’Alembert had tried to keep the assembly together: “he brings his friends together three days a week; but everyone in these assemblies is convinced that women fill the intervals of conversation and of life, like the padding that one inserts in cases of china; they are valued at nothing, and [yet] everything breaks without them.”[67]

However, although most guests were pleased with the salonnière’s control of the salon, there was some resentment by men who saw women and their role of leading the salon as a hindrance, not an aid, to good conversation. Jean-Jacques Rousseau—who was not a salon habitué—was one of the salon’s most bitter critics. He found it debasing for men to have to amuse women, to be constricted by them, “always constrained in these voluntary prisons.”[68] He felt that women undermined the seriousness of the discussions and that they did little but present themselves as idols and expect the educated man to entertain them. Interestingly enough, this accusation of women presenting themselves as idols to be fawned upon by men is the same criticism of women in the coffeehouse. It is very likely that it was not the women themselves who were to blame, but instead the belief that the mere presence of women was a distraction to serious men. Furthermore, Rousseau accused salon conversation of being dull and shallow:

they talk about everything so everyone will have something to say; they do not explore questions deeply, for fear of becoming tedious, they propose them as if in passing, deal with them rapidly, precision leads to elegance; each states his opinion and supports it in few words; no one vehemently attacks someone else’s, no one tenaciously defends his own; they discuss for enlightenment, stop before the dispute begins; everyone is instructed, everyone is entertained, all go away contented.[69]

In this, salon conversation reflected society conversation in general, whose essential features were “speed and the art of moving on.”[70]

Rousseau was not alone in his criticism of female-controlled salons. Some salon habitués themselves chaffed at what they perceived as censorship. The philosophe André Morellet was a regular attendant of salons who criticized the control of conversation in his memoirs, despite the fact that he enjoyed salons enough to attend them on a nearly daily basis. Morellet wrote in his Mémoires of Madame Necker’s salon: “the conversation was good there, although a little constrained by the severity of madame Necker, around whom many subjects could not be touched, and who suffered above all from the liberty of religious opinions.”[71] He contrasted the control of the salons with the liberty found at Baron d’Holbach’s male-only dinners, where, Morellet insisted, “one was forced to listen to the freest, the most animated, and the most instructive conversation that ever was.”[72] Like the coffeehouses, a male-dominated area dedicated to conversation was seen as more free and open. However, the increased degree of liberty was not necessarily an improvement. The purpose of the salons was not to let conversation have free reign: salons valued harmony over open discourse. Salonnières felt that it was because of their rules, not in spite of them, that the conversation was so impressive. Without someone guiding the conversation, men were prone to talk over each other, to be long-winded and boring, and to be querulous, such as at the Baron’s where, Morellet admits, conversation sometimes “took the form of hand-to-hand combat, of which the rest of the group were silent spectators.”[73] The rules might be chaffing to some, but they were established and maintained “in order to guarantee harmony and the free exchange of ideas.”[74] As Madame Necker noted, the role of the salonnière was “to prevent anyone of her society from taking up too much room at the expense of others.”[75] It was the salon’s rules that allowed men to know that everyone would have an equal opportunity to speak and that they would not be forced to shout down their opponent, which created a more harmonious atmosphere that could be more conducive to conversation.

There is some evidence from the coffeehouses that the salonnières beliefs were well-founded. There were complaints in pamphlets that coffeehouses had “neither Moderators, nor Rules”[76] and were therefore “School[s]…without a Master” where “Education is here taught without Discipline” and “Learning (if it be possible) is here insinuated without Method.”[77] Furthermore, the violent squabbles that salonnières tried to protect against could be found in coffeehouses. With no one to carefully move into a new conversation when the old one became too heated, coffeehouse debate could degenerate “into squabble and conflict.”[78] One famous coffeehouse scuffle turned violent when Titus Oates threw his coffee into someone’s face, an event satirized in the poem The School of Politicks, with one of the patrons repeating the same action, screaming “but here’s my Dish of Coffee in your Face.”[79]

While conversation was essential to both salons and coffeehouses, it can be seen that salons had a slightly more controlled atmosphere. A liberal hostess could create a very permissive environment that allowed even controversial subjects such as politics to be discussed, but at the same time a more conservative hostess could suppress such conversation. As institutions with no such moderators, coffeehouses had no rules on which topics were taboo. Although this led to squabbles and suspicion of sedition, it also led to the image of coffeehouses as the home of free conversation.

Communication: The Printed Word

News was the lifeblood of both the salons and the coffeehouses. For centuries, news had been largely spread through churches, inns, and marketplaces. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, there were new forums of information. In London, the coffeehouse was one of the primary sources for news. Not only did was it a hub of conversation, but it was also a primary center for printed news in the form of newspapers and pamphlets. Contemporaries recognized this important function of coffeehouses and the narrator of the newspaper The Censor was not alone in his belief that “in order to see how the World runs, and gather Observations on the Humours of Mankind” he needed to “constantly appear once a Day at the Coffee-houses.”[80] Even foreigners noticed the connection between news and coffeehouses. Charles Lewis Pollnitz, a Prussian nobleman staying in London in the 1730s, described how it was a “sort of Rule with the English, to go once a Day at least, to Houses of this Sort, where they talk of Businness and News” and “read the Papers.”[81]

Newspapers were a central feature of coffeehouses and one of their central draws. In his Dictionary, Samuel Johnson even defined a coffeehouse as “a house of entertainment where coffee is sold, and the guests are supplied with newspapers,”[82] suggesting that newspapers were an indispensable part of coffeehouse life. Coffeehouse keepers understood the close ties between their establishments and the newspapers and carried subscriptions to a wide variety of papers in order to draw in customers. What is remarkable is that these papers were both local and foreign. Macky noted that available newspapers included “not only the Foreign Prints, but several English ones with the Foreign Occurrences.”[83] A coffeehouse patron could often peruse papers from the Continent, including some from Paris and Amsterdam.[84] For the price of coffee, a man could read all the papers that a coffeehouse supplied. Indeed, “for a penny, you may have all the news in England, and other Countries; of Murders, Floods, Witches, Fires, Tempests, and what not, in the weekly news-books.”[85] At the time, the price of a penny would be equivalent to the cost of “lozenges at the apothecary, entry to the animals at the Tower [of London], having a dog wormed and a bread-roll at the bakers.”[86] Thus, coffeehouses were a bargain for those who enjoyed having unlimited access to newspapers. As one pamphlet observed: “he that comes often saves two pence a week in Gazets, and has his News and his Coffee for the same charge.”[87] Reading the newspapers in the coffeehouses quickly became a habit for Londoners and a 1712 issue of The Spectator noted that “there is no Citizen…that can leave the Coffee-house with Peace of Mind, before he has given every one of them a Reading.”[88]

Newspapers and coffeehouse conversation quickly developed a symbiotic relationship. Papers were obviously a great source of fodder for coffeehouse conversation, as John Gay wrote: “The Spectator, whom we regard as our shelter from that Flood of False Wit and Impertinence which was breaking in upon us, is in everyone’s Hand, and a constant Topick for our Morning Conversation at Tea-Tables and Coffee-Houses.”[89] However, coffeehouse conversation was also a rich source of information for newspapers. Papers like Addison’s immensely popular The Tatler were not only read in the coffeehouses, but were also “generated from” the coffeehouses.[90] In the first issue of The Tatler, Addison informed his audience that each section of his paper would be designated under the title of a famous coffeehouse: “all Accounts of Gallantry, Pleasure, and Entertainment, shall be under the Article of White’s Chocolate-house; Poetry under that of Will’s Coffee-house; Learning under the Title of Graecian; Foreign and Domestick News, you will have from St. James’s Coffee-house.”[91] The fame of these coffeehouses correlated with what subjects Addison listed under them: White’s was known as a place for gallants, Will’s was for wits, the Grecian was full of scientists and law professionals, and St. James’ was the home of Whigs (Addison’s political orientation). The fact that Addison organized his paper in such a way suggests that readers were familiar with the stereotypes of these coffeehouses and that these establishments were appropriate places for gathering news.

Addison took this relationship to the next level with his paper, The Guardian, which “was purely and simply the news sheet of Button’s Coffee-House.”[92] In 1713, Addison urged his readers to actively contribute to his paper by placing a Lion’s Head letterbox in Button’s. The Lion’s Head was to be the receptacle for letters that Addison would use in his paper and promised that “whatever the Lion swallows I shall digest for the Use of the Publick.”[93] As he explained in the Guardian: “I intend to publish once every Week the roarings of the Lion, and hope to make him roar so loud as to be heard over all the British nation.”[94]

The symbiotic relationship between newspapers and coffeehouses led to a confrontation between coffeehouse keepers and newspaper publishers revealed by pamphlets they published on the matter. The coffeehouse keepers felt that the cost of subscription was too high, since “a Paper once received into a Coffee-House is not easily dismiss’d”[95] and therefore they had to keep subscribing to a paper even if it had a limited following, for

’tis plainly a difficult and a

hazardous Thing for a Coffee-

Man to leave off a Paper he has

once taken in: For his Customers

seeing it once in his House,

always expect to see it

again…every Paper in a Coffee-

House has its Set of

Partizans…And if a Coffee-Man

turns a foolish rascally Paper out

of Doors, ‘tis ten to one but some

or other of his Customers follow

it, and he sees no more of them.[96]

They decided that it would be better if they cut out the middleman (the newspaper publishers) and publish their own papers, for “the Coffee-Houses being the Grand Magazines of Intelligence, the Coffee-Men…will be better able to furnish the Town with News-Papers, than any other Persons whatever.”[97] Indeed,

there is not an Accident happens

in or about Town, which some or

other of the Gentlemen, using the

Coffee-Houses, have not

Opportunities of knowing; nor a

Town or Village in the Kingdom,

from whence some or other of the

said Gentlemen have not Advices

of every Event and Occurrence.[98]

coffeemen decided that they would leave two tablets up in the businesses: one in the morning and one at night. There patrons could anonymously leave news and information that the coffeemen would write up in their newspapers. Knowing that their places of business were centers of news, they were confident that their patrons could supply enough news to publish two papers a day, a morning and an evening edition.[99]

The newspaper publishers responded to the “stupid Pamphlet” with one of their own.[100] They derided the idea of the “ignorant and impertinent”[101] coffeehouse keepers starting their own paper, since they were, “excepting a very few Widows and single Women, and a very few Men…the very servilest and most contemptible of that Part of Mankind which pretends to subsist by Trade.”[102] However, they did freely agree that newspapers were central to coffeehouse life: “it was just and natural, indeed, for them to think their Houses Places of Publick Resort, where Gentlemen often meet to read the Publick Papers, and from the Topicks furnish’d by them, descant on what they read, and fall into Conversation upon these Occasions.”[103] The pamphlet continually insisted that the coffeehouses only made money because of the presence of the papers: “the main Inducement to Gentlemen to use their Houses, is undoubtedly, to read the Papers of the Day, and there is no Paper publish’d, but often affords something curious that another has not.”[104] They also protested the idea that they made too much money off coffeehouse subscriptions, instead complaining that coffeehouses actually hurt their business, since “many a Paper would be bought by Gentlemen, if they could not so readily satisfy their Curiosities at the Coffee-House.”[105] They also countered the idea of the coffeehouses setting up their own paper by insisting that they would then establish their own coffeehouse. Neither of these threats came to pass, and the main legacy of these pamphlets is to show how both publishers and coffeehouse keepers recognized the great connection between coffeehouses and newspapers.

News was likewise critical to salon life. Indeed, “there were certain salons that were known as news bureaus.”[106] However, the main source of news in the salons was not papers but instead was correspondence, which was “the primary means for the transmission and circulation of news.”[107] Salon mail was meant to be read aloud and often provided topics for conversation. Correspondence, like the newspapers in the coffeehouses, played a dual role. It was both a source of discussion and was a way to spread salon conversation. It is believed that “news items that found their way into a correspondance but not anywhere else were probably gleaned from salon conversation.”[108] An example of a salon particularly tied to news, both as a consumer and as a source, can be found at Madame Doublet’s. There, guests recorded “certain” and “doubtful” news in separate registers and then discussed what they had written down. This news was so central to the salon that “the conversation in Doublet’s salon revolved around the news items gathered by her guests.”[109] An especially enterprising salonnière, Doublet turned her salon conversation into newsletters, a practice that some others followed. Doublet developed her registers into weekly newsletters which were copied and sold by her valets and bought in Paris, the provinces, and possibly even abroad.[110] Information in these newsletters included reports of social affairs such as deaths and marriages, but also more substantial reports on war-time events and the relationship between king and parliament.[111]

Centers of Criticism

By gathering together intellectuals who engaged in critical debate, coffeehouses and salons soon became seen as being able to pass judgment on a work or artist. Will’s Coffeehouse was especially well-known as the place for young writers to flock to in order to gain legitimacy. The English poet and critic John Dryden made his home there and would pronounce his opinion on the latest literary work or play. Dryden and his followers made Will’s the home of wits, which one French gentleman called “the Temple of the Muses, where all Poets and Wits are to be initiated.”[112] Dryden’s role was like that of the fictional Mr. Town who was described in Memoirs of a Bedford Coffeehouse as a figure “who gave the word, and judgment was accordingly pronounced [on a new piece]. This judgment was always ratified immediately after the performance at an assembly held at the Bedford, which was thenceforward, without appeal, irrevocable.”[113] Participation in coffeehouse life could thus be very important in a writers’ career and his reputation could depend on the judgment of the coffeehouse men.

Similarly, salons often served as launching pads for writers and as places to read their latest works. At Madame de Lambert’s, writers submitted manuscripts to the salons for judgment, and the great philosopher Montesquieu would often go to the salon for advice and critiques of his works.[114] Not only were there potential patrons available at the salons, but they also contained “all the wit of the wittiest capital in Europe”[115] who, like the wits of Will’s, could give advice or authority to works. Reading a manuscript aloud in the salons allowed a writer to find supporters who would help him publish his work and advance his career. In 1770, the playwright La Harpe read his play, Mélanie, ou La Religieuse, aloud in numerous salons and the reputation that the play earned from these readings helped it to sell 2,000 copies in a few days.[116] At the salons, reading aloud manuscripts “could be either an alternative to publication or as a stepping-stone to it.”[117] The salon was a superb place for artists to establish themselves as well. In Madame Geoffrin’s salon, artists could meet both collectors from France and possible patrons and buyers from among the many foreign guests.[118] Salons could further advance the reputation and careers of its habitués due to the influence of the salonnière on the election into the prestigious Académie Française. Madame Lambert was noted for her role in the process and her salon “usually had its own candidates whose success was virtually guaranteed.”[119] As a result, her salon was known as the “ante-chamber of the Academy.”[120] Several important figures owed their election to the Académie to the help of salon women, such as Montesquieu (supported by Madame Lambert)[121] and Marivaux (aided by Madame de Tencin).[122]

How the Other Half Lives: Cafés in Paris and Bluestockings in London

The coffeehouses of London and the salons of Paris were not completely unique entities, but they were the most important ones of their kind. While there were cafés in Paris and salons in London, neither were quite the same as their counterparts. The salons in London, better called Bluestocking assemblies, had the same central role of the hostess and emphasis on witty conversation as the Parisian salons. However, the Bluestocking assemblies did not have the longevity of their counterparts and were rather small and short-lived, lasting only from about 1750 to 1790.[123] Furthermore, they never gained the fame and influence of the Parisian salons.

Cafés, likewise, shared some of the salient features of the coffeehouses: both were centers of discussion and news, and both were filled with “people of all conditions,”[124] although it appears that the cafés were more luxurious and up-scale than coffeehouses, as can be seen by their fancier interior decoration. The standard was set by the Café Procope, Paris’ first successful café, which opened in 1689.[125] The interior of Procope was sumptuous and included expensive mirrors, a design feature copied by many cafés, especially those serving the literary elite. In these cafés, mirrors, marble tabletops and crystal chandeliers gave a sense of opulence to the surroundings.[126] This was in contrast to the interior of most London coffeehouses, which “did not look much different from taverns or alehouses on the outside, or even the inside.”[127] Instead of being full of glass, marble and crystal, coffeehouses tended to have wooden interiors and were mainly one room affairs “with one or more tables laid out to accommodate customers” although more prosperous ones might have a private room as well.[128]

The more upscale features of the cafés were also visible in what they served. While such coffeehouse staples as coffee and chocolate were available, cafés also provided brandies, liquor, beer, ice cream, sorbet and “an array of exotic pastries and confections.”[129] The amount of alcohol consumed made cafés more like an upscale tavern than a coffeehouse, since, as Ellis claims, “from their inception, the primary commodity sold in French cafés was alcoholic drink.”[130] While English coffeehouses were also allowed to sell liquor, their main offerings were the nonalcoholic beverages of tea, chocolate, and coffee.[131]

Entertainment likewise went beyond the scope of most coffeehouses, with gaming quite popular at cafés. In fact, in 1789 one Polish visitor to England noted: “an English coffee-house has no resemblance to a French or German one. You neither see billiards nor backgammon tables.”[132] While gaming was done at very upscale coffeehouses, such as White’s Chocolate House, in general coffeehouses avoided gambling. Thus it seems that cafés catered more to the wealthy and those interested in entertainment than the more serious and less luxurious coffeehouses.

It’s the End of the World as We Know It: The Close of the Golden Age of Coffeehouses and Salons

By the end of the eighteenth century, the Golden Age of salons and coffeehouses was over. The decline of the coffeehouses was directly correlated with the rise of the club. While there had been clubs meeting at the coffeehouses since the 1650’s, coffeehouses themselves eventually transformed into clubs. White’s Chocolate House was the first to do so, in 1773, and others soon followed its example. Coffeehouses such as St. James’, the Cocoa-tree, and Tom’s changed from open, egalitarian institutions to exclusive establishments. Clubs also accelerated the demise of the coffeehouses by replacing them as the centers of intellectual discourse. While before men satisfied their interests in politics and literature and their craving for debate by going to the coffeehouse, they now joined a club.

Other factors contributed to the coffeehouse’s disappearance as a phenomenon. Circulating libraries became the new dispensers of literature and newspapers, the newspapers themselves employed reporters instead of relying on coffee house gossip, and transportation and the postal service improved. All these factors decreased the importance and usefulness of the coffeehouse. The government’s colonial policies also helped to kill coffeehouse culture. The East India Company had been the main grower and supplier of coffee, but new trade routes to China and India led to greater importation of tea. While tea prices dropped in the 1750s, coffee prices rose.[133] This led to a reduction in the sale of coffee, and hurt the coffee houses financially. In 1777, Samuel Foote lamented “’the disappearance of the coffee houses where the town wits met of an evening.’”[134] While coffeehouses continued to exist, the coffeehouse culture that had added so much to British life had faded.

The salons also saw their membership drift away to other public sphere institutions, and by the 1780s they had begun to lose their status as the premier centers of discussion. Some historians, such as Joan Landes and Dena Goodman, have argued that this was due to changing male attitudes towards the salon and a growing preference by them for more male-dominated institutions. James Melton has countered that some of the alternative public sphere institutions, such as cafés and theater, were not as exclusively male as Goodman has implied and thus an increasing masculinization of the public sphere is not the true cause of the decline of the salon.[135] However, it is also true that these institutions were not so thoroughly connected with women as the salons. In the end, it was the bloody revolution that began in 1789 that rang the death knell of the great salons. Like coffeehouses, the salons did not disappear entirely, but their central importance to the public sphere had ended.

Coffeehouses and salons continue to be seen as being very important during the height of their influence. Both were institutions of the public sphere, whose emphasis on sociability, equality and communication helped to circulate important Enlightenment ideas to different classes. Although neither coffeehouses nor salons were as egalitarian as some made them out to be, they were nonetheless important centers of social mixing and egalitarianism for their time. However, coffeehouses and salons also reveal slightly different aspects of the Enlightenment public sphere. Coffeehouses were more open and less structured, with a greater range of social classes and more of an emphasis on print culture. Salons, on the other hand, although they gave an important role to women, were a more private aspect of the public sphere, a mixing of classes that occurred only with an invitation. However, what is most important is not the differences, but the similarities, that both these institutions found a way to meet the needs of two different countries to create a space where people could interact outside the court and the home to discuss and circulate important ideas.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Coffee-houses Vindicated in Answer to the Late Published Character of a Coffee-House (1673) in Eighteenth-Century Coffee-House Culture, vol. 1, ed. Markman Ellis (London: Pickering & Chatto, London, 2006), 97.

- Markman Ellis, ed. Eighteenth-Century Coffee-House Culture (London: Pickering & Chatto, 2006), 172.

- M.P., A Character of Coffee and Coffeehouses (1661), in Eighteenth-Century Coffee-House Culture, vol. 1, ed. Markman Ellis (London: Pickering & Chatto, London, 2006), 6.

- Benedetta Craveri, Teresa Waugh (trans), The Age of Conversation (New York: New York Review of Books, 2005), 27.

- Ellis, Eighteenth-Century Coffee-House Culture, xix.

- Louis Batiffol, et al., Mabel Robinson (trans), The Great Literary Salons (XVII and XVIII Centuries) (London: Thornton Butterworth, 1930), 140.

- James Melton, The Rise of the Public in Enlightenment Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 3-4.

- Jürgen Habermas, Thomas Burger (trans). The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1989), 36-7.

- Dena Goodman, “Public Sphere and Private Life: Toward a Synthesis of Current Historiographical Approaches to the Old Regime,” History and Theory, vol. 31 (February 1992), 19.

- Brian Cowan, The Social Life of Coffee: The Emergence of the British Coffeehouse (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005), 2.

- DenaGoodman, The Republic of Letters (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1994), 5.

- Michael Delon, ed. Encyclopedia of the Enlightenment, volume 1 (London: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 2001), 1178.

- Helen Clergue, The Salon: A Study of French Society and Personalities in the Eighteenth Century (Burt Franklin: New York, 1971), 340.

- Marguerite Glotz and Madeleine Maire, Salons du XVIIeme siècle (Paris: Nouvelles Editions Latines, 1949), 14.

- Guardian 114 in The Commerce of Everyday Life: Selections from The Tatler and The Spectator, ed. Erin Mackie (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s), 165.

- John Macky, A Journey Through England. In Familiar Letters. From a Gentleman Here, to his Friends Abroad (1714) in Eighteenth-Century Coffee-House Culture, vol. 1, ed. Markman Ellis (London: Pickering & Chatto, London, 2006), 339.

- The Life and Character of Moll King (1747) in Eighteenth-Century Coffee-House Culture, vol. 2, ed. Markman Ellis (London: Pickering & Chatto, London, 2006), 204.

- A Sunday Ramble; or, Modern Sabbath-Day Journey: in and about the Cities of London and Westminster (1776) in Eighteenth-Century Coffee-House Culture, vol. 2, ed. Markman Ellis (London: Pickering & Chatto, London, 2006), 360.

- Houghton, A Collection of the Improvement of Husbandry and Trade, in Cowan, 99.

- The Character of a Coffee-House (1665), 66-71.

- Macky, 336.

- Ibid.

- Ellis, The Coffee House: A Cultural History, 150-1.

- Spectator no. 1, in The Commerce of Everyday Life: Selections from The Tatler and The Spectator, ed. Erin Mackie (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s), 80.

- Spectator no. 49, in The Commerce of Everyday Life: Selections from The Tatler and The Spectator, ed. Erin Mackie (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s), 92.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, 93.

- Craveri, 313.

- Goodman, Republic of Letters, 149.

- Craveri, 302.

- Clergue, 23.

- Glotz & Maire, 25.

- Clergue, 81.

- Glotz & Maire, 25.

- Craveri, p. 291.

- Ibid, 295.

- Cowan, 149.

- M.P., A Character of Coffee and Coffeehouses (1661), in Eighteenth-Century Coffee-House Culture, vol. 1, ed. Markman Ellis (London: Pickering & Chatto, London, 2006), 9.

- “Brief Description” in Ellis vol. 1, 129.

- A Character of Coffee (1661), 9-10.

- The Character of a Coffee-House (1673), 87.

- Carolyn Lougee, Le Paradis des Femmes: Women, Salons, and Social Statificatin in Seventeenth-Century France (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1976), 170.

- Hall, 45.

- Craveri, 35.

- Ibid., 263.

- In Craveri, 293.

- Lougee, 52.

- Craveri, 312.

- Hall, 40.

- Battifol, 138.

- Ellis, Eighteenth-Century Coffee-House Culture, vol 2, xi.

- Glotz and Maire, 19-20.

- Macky, 339.

- The Character of a Coffee-House (1665) in Eighteenth-Century Coffee-House Culture, vol. 1, ed. Markman Ellis (London: Pickering & Chatto, London, 2006), 68.

- The Character of a Coffee-House (1673), 89.

- Ibid., 85.

- Ibid, 86.

- Cowan, 148.

- Craveri, 345.

- Louis Batiffol, et al., Mabel Robinson (trans), The Great Literary Salons (XVII and XVIII Centuries) (London: Thornton Butterworth, 1930), 130.

- Delon, 1179.

- Batiffol, 170.

- Craveri, 302.

- Evelyn Beatrice Hall, The Women of the Salons and Other French Portraits (Freeport, New York: Books for Libraries Press, 1969), 47.

- Battifol, 43.

- In Goodman, Republic of Letters, 100.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, 55.

- In Craveri, 356.

- Craveri, 366.

- In Goodman, Republic of Letters, 107.

- Ibid, 109.

- Ibid, 110.

- Craveri, 358.

- Goodman, Republic of Letters, 110.

- A Character of Coffee (1661) in Eighteenth-Century Coffee-House Culture, vol. 1, ed. Markman Ellis (London: Pickering & Chatto, London, 2006), 13.

- Ibid.

- Markman Ellis, Coffee-house: A Cultural History (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2004), 62.

- The School of Politicks: or, the Humours of a Coffee-House. A Poem (1690) in Eighteenth-Century Coffee-House Culture, vol. 1, ed. Markman Ellis (London: Pickering & Chatto, London, 2006), 229.

- Lewis Theobold, “No. 61: Coffee-House Humours Exposed” (1717) in Eighteenth-Century Coffee-House Culture, vol. 1, ed. Markman Ellis (London: Pickering & Chatto, London, 2006), 345.

- Memoirs of Charles-Lewis, in Ellis, vol 1, xii.

- Johnson, in Ellis, The Coffee House, xi.

- Macky, 339.

- Cowan, 174.

- The Worth of a Penny in Ellis, The Coffee House, 65.

- Ibid.

- The Character of a Coffee-House (1673), 85.

- Mackie, 104.

- Ibid, 155.

- Ibid, 16.

- The Tatler no. 1, in The Commerce of Everyday Life: Selections from The Tatler and The Spectator, ed. Erin Mackie (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s), 50.

- Ulla Heise, Coffee and Coffee-Houses (West Chester, PA: Schiffer Publishing, 1987), 132.

- Mackie, 163.

- Ibid, 165.

- Coffee Men, The Case of the Coffee-men of London and Westminter [sic] (1728) in Eighteenth-Century Coffee-House Culture, vol. 2, ed. Markman Ellis (London: Pickering & Chatto, London, 2006),104.

- Ibid, 105.

- Ibid, 113.

- Ibid, 128.

- Ibid., 111-13.

- The Case Between the Proprietors of News-papers and the Subscribing Coffee-men, Fairly Stated (1729) in Eighteenth-Century Coffee-House Culture, vol. 2, ed. Markman Ellis (London: Pickering & Chatto, London, 2006), 135.

- Ibid, 139.

- Ibid, 140.

- Ibid, 136.

- Ibid., 142.

- Ibid., 145.

- Dena Goodman, “Enlightenment Salons: The Convergence of Female and Philosophic Ambitions,” Eighteenth-Century Studies, no. 22 (1989), 343.

- Goodman, Republic of Letters, 142.

- Ibid., 163.

- Ibid., 155.

- Ibid, 156.

- Ibid., 146.

- “Letter from a French Gentleman in London to his friend in Paris…Containing an Account of Will’s Coffeehouse, and of the Toasting of the Kit-Kat-Clubs” (1701) in Eighteenth-Century Coffee-House Culture, vol. 1, ed. Markman Ellis (London: Pickering & Chatto, London, 2006), 250.

- Memoirs of a Bedford Coffeehouse, By a Genius (1763) in Eighteenth-Century Coffee-House Culture, vol. 2, ed. Markman Ellis (London: Pickering & Chatto, London, 2006), 283.

- Craveri, 268.

- Hall, 26.

- Goodman, Republic of Letters, 146-7.

- Goodman, «Enlightenment Salons», 344.

- Craveri, 300.

- Ibid.

- Clergue, 13.

- Delton, 1177.

- Ibid., 1178.

- Bodek, 187.

- Francois Fosca, Histoire des Cafés de Paris (Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1934), 26.

- Heise, 104.

- Thomas Brennan, Public Drinking and Popular Culture in Eighteenth-Century Paris (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1998), 129-32.

- Cowan, 79.

- Ibid.

- Brennan, 112.

- Ellis, Coffee-House Culture, 81.

- Cowan, 80.

- Johann Wilhelm Von Archenholz, A Picture of England: Containing a Description of the Laws, Customs and Manners of England (1789) in Eighteenth-Century Coffee-House Culture, vol. 2, ed. Markman Ellis (London: Pickering & Chatto, London, 2006), 373-4.

- Norma Aubertin-Potter and Alyx Bennett, Oxford Coffee Houses, 1651-1800 (Oxford: Hampden Press, 1987), 16.

- In Bertha Maude, The Coffee-Houses of the 18th Century (Burleigh Catholic Press, 1933), 24.

- Melton, 210.

Primary Sources

- A Sunday Ramble; or, Modern Sabbath-Day Journey: in and about the Cities of London and Westminster. London: 1776. In Eighteenth-Century Coffee-House Culture, ed. Markman Ellis, London: Pickering & Chatto, 2006, vol 2.

- Berger, Morroe (ed. & trans). Madame de Stael on Politics, Literature, and National Character. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1964.Boswell, James. Frederick Pottle (ed).

- Boswell’s London Journal, 1762-1763. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1950.

- Coffee-houses Vindicated in Answer to the Late Published Character of a Coffee-House, London, 1673. In Eighteenth-Century Coffee-House Culture, ed. Markman Ellis, London: Pickering & Chatto, 2006, vol 1.

- Coffee-man. The Case of the Coffee-men of London and Westminter [sic]. By a coffee-man. London: 1728. In Eighteenth-Century Coffee-House Culture, ed. Markman Ellis, London: Pickering & Chatto, 2006, vol 2.

- “Letter from a French gentleman in London to his friend in Paris…Containing an Account of Will’s Coffeehouse, and of the Toasting and Kit-Kat-Clubs.” London: 1701. In Eighteenth-Century Coffee-House Culture, ed. Markman Ellis, London: Pickering & Chatto, 2006, vol 1.

- Mackie, Erin (ed). The Commerce of Everyday Life: Selections from The Tatler and The Spectator. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s.

- Macky, John. A Journey Through England. In Familiar Letters. From a Gentleman Here, to his Friend Abroad. London: 1714. In Eighteenth-Century Coffee-House Culture, ed. Markman Ellis, London: Pickering & Chatto, 2006, vol 1.

- Memoirs of the Bedford Coffee-House. By a Genius. London: 1763. In Eighteenth-Century Coffee House Culture, ed. Markman Ellis, London: Pickering & Chatto, 2006, vol 2.

- M.P., A Character of Coffee and Coffee-Houses, London: 1661. In Eighteenth-Century Coffee House Culture, ed. Markman Ellis, London: Pickering & Chatto, 2006, vol 1.

- Morellet, Andre. Eloges de Madame Geoffrin, Contemporaine de Madame du Deffand. Paris: H. Nicolle Libraire Stéréotype, 1812.

- The Case Between the Proprietors of News-papers, and the Subscribing Coffee-men, Fairly Stated. London: 1729. In Eighteenth-Century Coffee House Culture, ed. Markman Ellis, London: Pickering & Chatto, 2006, vol 2.

- The Character of a Coffee-House. By an Eye and Ear Witness. London: 1665. In Eighteenth-Century Coffee House Culture, ed. Markman Ellis, London: Pickering & Chatto, 2006, vol 1.

- The Character of a Coffee-House, with the Symptomes of a Town-Wit. With Allowance, April 11th 1673. London: 1673. In Eighteenth-Century Coffee House Culture, ed. Markman Ellis, London: Pickering & Chatto, 2006, vol 1.

- The Life and Character of Moll King. London: 1747. In Eighteenth-Century Coffee-House Culture, ed. Markman Ellis, London: Pickering & Chatto, 2006, vol 2.

- The School of Politicks: or, the Humours of a Coffee-House. A Poem. London: 1690. In Eighteenth-Century Coffee House Culture, ed. Markman Ellis, London: Pickering & Chatto, 2006, vol 1.

- Theobald, Lewis. “No. 61: Coffee-House Humours Exposed.” London: 1717. In Eighteenth-Century Coffee House Culture, ed. Markman Ellis, London: Pickering & Chatto, 2006, vol 1.

- von Archenholz, Johann Wilhelm. A Picture of England: Containing a Description of the Laws, Customs and Manners of England. London: 1789. In Eighteenth-Century Coffee House Culture, ed. Markman Ellis, London: Pickering & Chatto, 2006, vol 2.

Secondary Sources

- Aubertin-Potter, Norma and Alyx Bennett. Oxford Coffee Houses, 1651-1800. Oxford: Hampden Press, 198.

- Batiffol, Louis, et al. Mabel Robinson (trans.). The Great Literary Salons (XVII and XVIII Centuries). London: Thornton Butterworth, 1930.

- Brennan, Thomas. Public Drinking and Popular Culture in Eighteenth-Century Paris. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1998.

- Clergue, Helen. The Salon: A Study of French Society and Personalities in the Eighteenth Century. Burt Franklin: New York, 1971.

- Cowan, Brian. The Social Life of Coffee: The Emergence of the British Coffeehouse. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005.

- Craveri, Benedetta. Teresa Waugh (trans). The Age of Conversation. New York: New York Review of Books, 2005.

- Delon, Michel (ed.). Encyclopedia of the Enlightenment. London: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 2001, vol. 1.

- Ellis, Markman (ed). Eighteenth-Century Coffee-House Culture. London: Pickering & Chatto, 2006, vol 1 and 2.

- The Coffee House: A Cultural History. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2004.

- Fosca, Francois. Histoire des Cafés de Paris. Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1934.

- Glotz, Marguerite and Madeleine Maire. Salons du XVIIIeme siècle. Paris: Nouvelles editions Latines, 1949.

- Goodman, Dena. “Enlightenment Salons: The Convergence of Female and Philosophic Ambitions.” Eighteenth-Century Studies. 22.3 (Spring 1989), 329-50.

- “Public Sphere and Private Life: Toward a Synthesis of Current Historiographical Approaches to the Old Regime,” History and Theory, 31.1. (February 1992), pp. 1-20

- The Republic of Letters: A Cultural History of the French Enlightenment. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1994.

- Gordon, Daniel. “’Public Opinion’ and the Civilizing Process in France: The Example of Morellet.” Eighteenth-Century Studies. 22.3 (Spring 1989).

- Habermas, Jürgen. Thomas Burger (trans). The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1989.

- Hall, Evelyn Beatrice. The Women of the Salons and Other French Portraits. Freeport, New York: Books for Libraries Press, 1969.

- Heise, Ulla. Coffee and Coffee-Houses. West Chester, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing, 1987.

- Lougee, Carolyn. Le Paradis des Femmes: Women, Salons, and Social Stratification in Seventeenth-Century France. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1976.

- Maude, Bertha. The Coffee-Houses of the 18th Century. Burleigh Catholic Press, 1933.

- Melton, James. The Rise of the Public in Enlightenment Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Originally published by the Colgate Academic Review 3:7 (Spring 2008, 75-99), Digital Commons @ Colgate, Digital Commons Network, republished with permission under a free and open access license.