It is impossible to say exactly when in 1348 the plague burst the bubble of English exuberance, but the country was still in an it-can’t-happen-here frame of mind.

By John Kelly

Historian and Author

Southwest England, Summer 1348

IN 1348 ENGLAND’S MORALISTS WERE IN A SOUR MOOD. THE monk Ranulf Higden saw pretension everywhere. These days, thundered Higden, “a yeoman arrays himself as a squire, a squire as a knight, a knight as a duke, and a duke as a king.” The chronicler of Westminster saw an even more pernicious threat—medieval Spice Girls everywhere! Englishwomen, complained the chronicler, “dress in clothes that are so tight, . . . they [have to wear] a fox tail hanging down inside of their skirts to hide their arses.”

However, hardly anyone paid attention to the carping. As mid-century approached, the green and pleasant land of England was in an exuberant mood. The country was flush with military success, awash in French war booty, and best of all, England had a king it could love again. Edward II, the former sovereign, had been a puzzlement to his people. Kings were supposed to like wars, hunting, jousting, and women, but Edward’s tastes had run to theatricals, arts and crafts, minstrels—and men. In a guarded reference to the old king’s homosexuality, a chronicler wrote that Edward loved the knight Piers Gaveston more than his wife, the beautiful French princess Isabella. In a reign marked by military defeat, famine, and political turmoil, Edward, who gained a reputation for being “chicken-hearted and luckless,” lost the support of the English nobility, and, after a coup by Isabella and her lover Roger Mortimer, met death in the vilest imaginable manner. According to legend, Edward’s last moments on earth were spent with a hot plumber’s iron in his anus.

The only nice thing the author of The Reign of Edward II had to say about his subject was that Edward had been remarkably wealthy.

He was also quite handsome, a trait he shared with his son and successor, but otherwise Edward III was everything his father was not: glamorous, romantic, politically deft—and bold. In 1330, at the age of seventeen, Edward seized England’s imagination—and avenged his father’s memory—by bursting into his mother’s bedchamber and arresting the treacherous Mortimer at swordpoint. “Good son, good son, be gentle with dear Mortimer,” the queen pleaded, as her lover was led away in chains. However, it was the victory over the French at Crécy in 1346 that turned Edward III into an English demigod. When the chronicler Thomas Walsingham wrote, “[I]n the year of grace 1348, it seemed to the English that, as it were, a new sun was rising over the land,” he was thinking of the glorious August morning two years earlier when Edward, in a Shakespearean moment, leaped upon his horse in a field outside Crécy and, with the morning sun at his back, “rode from rank to rank . . . desiring every man to take hede . . . [speaking] so sweetly and with so good countenance and merry cheer, that all such as were discomforted took courage.”

In 1348, Walsingham’s “new sun” also shone over a nation more politically and socially stable than it had been in more than a generation—and more prosperous than one might expect, given the terrible deprivations of the famine years. In 1348 demand for English wool was such that English sheep outnumbered English people—roughly eight million sheep versus six million humans. And there were the first stirrings of an industrial economy—in the west country and East Anglia, where cloth was being made, and in Wales and Cornwall, where coal and tin were being mined. Meanwhile along the coast, the timber-faced waterfronts of Bristol, Portsmouth, London, and Southampton bustled with high-masted ships from Flanders, Italy, Gascony, and the German towns of the Hanseatic League.

It is impossible to say exactly when in 1348 the plague burst the bubble of English exuberance, but during the early months of the year, the country still seemed in an it-can’t-happen-here frame of mind. In January and February, while Avignon was running out of cemeteries, Edward was at Windsor, redecorating the chapel and coyly avoiding the Germans, who were said to want to offer him the emperor’s crown; meanwhile, his subjects were shamelessly parading around the English countryside in stolen French war booty. “There was no woman of any standing who had not her share of the spoils of Calais, Caen and other places across the Channel,” wrote Walsingham. Strengthening the it-can’t-happen-here mood was the fact that the plague was ravaging France, and the insular English considered the French strange even for foreigners; as one contemporary English writer famously noted, your average Frenchman was effeminate, walked funny, and spent too much time fussing with his hair.

It is also difficult to say exactly what changed the national mood. Perhaps it was the onset of the rains in early summer. During the second half of 1348, “scarcely a day went by without rain at some time in the day or night.” Maybe, peering into the misty channel that May or June, the English felt a premonitory shudder of dread. Or maybe, more simply, by late spring—with nearly every town on the French side of the channel flying a black plague flag—the danger had become impossible to ignore, even for an island people accustomed to thinking of themselves as a breed apart.

The summer of 1348 was, like the Battle of Britain summer of 1940, a time of stirring backs-to-the-wall rhetoric. “The life of men upon earth is warfare,” declared the Bishop of York in July. A month later, the Bishop of Bath and Wells warned his countrymen that the apocalypse was nigh. “The catastrophic pestilence from the east has arrived in a neighboring kingdom [France], and it is very much to be feared that unless we pray devoutly and incessantly, a similar pestilence will stretch its poisonous branches into this realm.”

We don’t know how many people took the bishop’s advice, but however many prayers the English offered to heaven in the rainy summer of 1348, they were not enough. Over the next two years, England would endure the worst catastrophe in its long national life. In the words of the Elizabethan playwright John Ford, between 1348 and 1350:

One news came straight huddling on another

Of death and death and death.

During those two years, perhaps 50 percent of England was consumed in the mortality.*

To Irish monk John Clynn, it felt as if the end of the world had arrived. Writing in the doomsday year of 1349, Clynn declared, “Waiting among the dead for death to come . . . , [I] have committed to writing what I have truly heard and examined . . . in case anyone should still be alive in the future.” Given the level of fear, rumor, and confusion current in the summer of 1348, it is probably inevitable that contemporary reports haveY. pestislanding at several different points along the English coast, including at Bristol in the west, Southampton and Portsmouth along the channel coast, and even in the north of England.* However, the weight of historical evidence points to Melcombe, a small port on the southwest channel coast, as the most likely initial landing site. Melcombe is mentioned more often than any other port in contemporary writings, including in the chronicle of Malmesbury Abbey, which says that “in 1348, at about the feast of . . . St. Thomas the martyr [July 7], the cruel pestilence, hateful to all future ages arrived from countries across the sea on the south coast of England at the port called Melcombe in Dorset.” TheGrey Friar’s Chroniclealso says that “In 1348, . . . two ships . . . landed at Melcombe in Dorset before Midsummer. . . . They infected the men of Melcombe who were the first to be infected in England.”

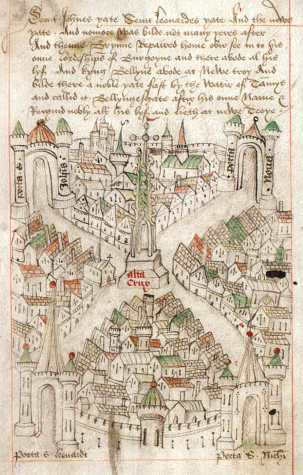

Today Melcombe is part of Weymouth, a pleasant channel resort town full of Regency architecture, bright seaside shops, towering cliffs, and history. A D-day memorial in the harbor commemorates the thousands of young Americans who left the town on a rainy June morning in 1944 for the beaches of Normandy; and a plaque near the docks commemorates the departure in 1628 of John Endicott, founder of the Salem colony and first governor of New England. However, the most famous moment in local history may have occurred on the north bank of the Wey, the river that runs through the modern town and gives Weymouth its name. In the Middle Ages, the flat alluvial plain above the north bank was occupied by the town of Melcombe, a name that means “valley where milk was got,” or, more simply, “fertile valley,” and that apparently originated with the Durotriges, the Celtic tribe who settled the Dorset coast.

In the 1340s Melcombe seems to have been larger and more prosperous than medieval Weymouth, which was squeezed into the narrow strip of land between the south bank of the Wey and the rugged Dorset cliffs—a position that gave it the aspect of being perpetually about to tumble into the English Channel. Melcombe boasted a larger fleet than Weymouth, a crowded trading quarter along Bakeres Street—as well as one of the richest men in the county of Dorset, Henry Shoydon, who in 1325 paid an astonishing forty shillings in taxes. A fourteenth-century map shows that in Shoydon’s time Melcombe also had a jetty, where visiting ships unloaded goods. Though it is hard to imagine today, in affluent modern Weymouth—surrounded by picture-taking Japanese tourists, T-shirted teenagers, and sleek young couples down from London—on a summer’s day in 1348, when the sky was heavy with rain, a vessel or several vessels docked at the jetty carrying “death and death and death.”

The vessel—or vessels—was probably returning from Calais, the scene of recent bitter fighting between the French and the English.* After menacing Paris in early August 1346, and defeating a much larger French force at Crécy, Edward swung north and attacked Calais, a walled city of around twenty thousand on what is left of the land bridge that linked Britain to the continent before the end of the last Ice Age. As fighting around the town degenerated into a brutal siege, little Melcombe, not for the last time, found itself drawn into great events across the channel. A surviving royal order from 1346 shows Edward requisitioning twenty ships and 246 mariners from the town to support the English forces in Calais. Some Melcombe men may even have been present a year later to witness one of the most glorious moments in French history. A committee of Calais’s leading citizens, the Six Burghers, appeared in the English camp and offered their lives if Edward would agree to spare their fellow citizens. The chronicler Jean le Bel says the English were so moved by the burghers’ bravery, “there was not a lord or knight . . . who wasn’t weeping out of pity.”

Even if Melcombe was not the very first English town to be infected by the pestilence, the links to Calais must have made it a very close second or third. Everything we know about the plague suggests that the French town would have been absolutely toxic with contagion in the summer of 1348. Cramped and walled off to begin with, Calais had just emerged from an eleven-month siege and thus would have been rich in filth, rats, and malnourished humans whenY. pestisarrived in the summer of 1348. On top of that, the English were sending home enormous amounts of “liberated” French war booty. “English ladies were proudly seen going about in French dresses” that summer, and English homes were full of French “furs, pillows, . . . linens, clothes and sheets.” Inevitably, some of the “liberated” goods sent home must have carried infected fleas. Additionally, plague-bearing rats most likely slipped into the holds of a few of the Melcombe ships fleeing Calais.

Whichever way the pestilence arrived, by the end of the summer of 1348, the only sounds to be heard in Melcombe were the patter of rain on thatched roofs and the roar of the pounding surf rising above the cliffs. The sole piece of information we have about the fate of the town is inferential. In the early 1350s Edward declared the island of Portland immediately to the south “so depopulated in . . . the late pestilence that the inhabitants remaining are not sufficient to protect it against our foreign enemies.” Melcombe’s subsequent incorporation into Weymouth suggests that its suffering was even more severe. It is unlikely that the proud townsfolk would have agreed to be incorporated by a smaller and historically less significant Weymouth unless Melcombe had become too weak to sustain itself.

The lack of a documentary record in Melcombe is unusual. As historian Philip Ziegler notes, contemporary English records “offer a fuller picture of the progress of the Black Death than those [of] any other country.” On the subject of human suffering, the documents—wills, deeds, manor records, clerical appointments, and property transfers—are not particularly enlightening, but they provide an illuminating guide toY. pestis’s movement and behavior. From the pattern of deaths in the records, for example, it is clear how cunningly the plague exploited England’s improving communications network, including the new road networks linking London in the east to Coventry in the midlands and Bristol in the west, and the river networks, which carried a great deal of internal trade. The new ferries and bridges—and the horse, which was replacing the lugubrious ox as a means of haulage—also helped to enhanceY. pestis’s mobility.

As Ziegler has noted, in its precision, the plague’s initial assault on southwestern England resembled a military campaign. To understand how the assault unfolded, a rudimentary geography lesson is necessary. The west coast of England is shaped like a galloping pig in profile. North Wales forms the pig’s floppy ear, central Wales its snout, and the Bristol Channel, below Wales, the space between the pig’s jaw and its outstretched, galloping leg. The leg, which thrusts out into the Atlantic, encompasses the southwest of England. On its ocean side, the region extends down the coast from the Bristol Channel to Land’s End in Cornwall, the most westerly point in England; and on its channel side up the backside of Cornwall and eastward to the neighboring channel counties of Devon and Dorset, where Melcombe is located.

By the winter of 1348–49, one prong of the pestilence, moving northward from Melcombe, and a second, moving eastward over land from the Bristol Channel (which was infected later in the summer) would intersect, and everything inside the galloping leg would be trapped in a plague pocket.

The Dorset coast is full of brooding Heathcliff vistas—windswept moors, moody gray skies, furiously moving clouds, turbulent reefs, and towering, chalk-faced cliffs, some so sheer they seem to have been cleaved from continental Europe with an ax. Here and there, nestled amid rock and wind and sea, are dozens of little coastal towns like Melcombe and its neighbors: Poole, Bridport, Lyme Regis, Wareham, and West Chickerell. In the Middle Ages, the towns were all sleepy little places where the same two hundred or three hundred sets of genes would chase one another around for centuries, and the rhythm of daily life was as unalterable as sea and sky. In the rainy autumn of 1348, this predictability begins to shatter. The secular records provide brief glimpses of the plague’s early progress through the coastal southwest, but the ecclesiastical rolls—especially the meticulously kept clerical mortalities—offer the most sustained view.

In the clerical records, if not in real life, the Black Death begins like a classic English mystery, perhaps an Agatha Christie thriller calledWho Is Killing the Priests of Coastal England?In October—a few months afterY. pestisarrives in Melcombe*—West Chickerell to the north and Warmwell and Combe Kaynes to the east suddenly lose priests; in November the clerical death wave spreads to nearby Bridport, East Lulworth, and Tynham, and in December to Settisbury, also nearby, which has to appoint three priests before finding one who won’t die on the town. John le Spencer was appointed to a clerical post in Settisbury on December 7, 1348; three days later he was succeeded by Adam de Carelton, who in turn was succeeded on January 4 by Robert de Hoven. In the last two months of 1348, thinly inhabited Dorset had to fill thirty-two clerical vacancies—fifteen in November and seventeen in December, an astonishing replacement rate. And the clerical deaths were just the beginning.

All along the coastal southwest in the black autumn of 1348, the living gathered in the rain to bury the dead. In Poole, to the east of Melcombe, the grave diggers worked to the roar of the pounding surf rolling across the Baiter, a sandy tongue of land converted into a seaside cemetery. In 1348 and early 1349, little Poole seems to have buried the better part of itself in the channel sand. One hundred fifty years later there were still so many abandoned buildings in the town, Henry VIII took time out from his complicated romantic affairs to order their repair. Centuries later, locals were still pointing out the Baiter and regaling visitors with stories of the terrible autumn of 1348, when death and rain howled down upon the town. To the west of Melcombe, in Bridport, which was famous for making the best nautical rope in England, townsfolk buried their dead with a dogged devotion to English legalism. To ensure that every death was properly recorded and processed, in the winter of 1348–49 Bridport doubled its normal complement of bailiffs from two to four. The ecclesiastical records also highlight what may have been the first metastasis of the pestilence. In November and December a sudden burst of clerical deaths in Shaftesbury in central Dorset suggests that the plague was now spreading northward through the incessant rain on an inland route that would carry it through the deer-filled forests and sprawling sheep farms of upper Dorset and into the English midlands.

In the seventeenth century, Clevedon, Bridgwater, and the other little towns along the Bristol Channel would become the last bit of green England that African slaves saw on their way to the West Indies. But in the gray, wet August of 1348, sorrow and misery sailed in the opposite direction—not out into the blue Atlantic, but up the channel toward Bristol. On a drizzly morning somewhere between August 1 and 15—chroniclers disagree on the date—an infected ship, or ships, probably from Dorset but possibly from Gascony, docked in Bristol harbor. Very shortly thereafter, the town, the largest seaport in the west of England, literally exploded. “Cruel death took just two days to break out all over town. . . . It was as if sudden death had marked [people] down beforehand,” wrote the monk Henry Knighton.

This was the second prong ofY. pestis’s assault, and it quickly turned Bristol into a charnel house. “The plague raged to such a degree,” says one writer, “that the living were scarcely able to bury the dead. . . . At this period,” he adds, “the grass grew several inches high in High Street and Broad Street.”

According to theLittle Red Book,a list of local government officials, fifteen of Bristol’s fifty-two city councilors died in 1349, a death rate of almost 30 percent. However, surviving ecclesiastical records suggest that Bristol’s clergy suffered far more grievously; one series of records shows that ten of eighteen local clerical posts had to be filled in 1349—a death rate of about 55 percent. The town historian estimates that 35 to 40 percent of Bristol died in the mortality.

Below the seaport, in the Bristol Channel town of Bridgwater, the Christmas of 1348 was desolate beyond imagination. The local water mill had stood idle since November, when William Hammond, the miller, died, and the autumn rains had turned the low-lying ground around the town into a swamp, ruining crops and making movement difficult. Then, over Christmas, while Bridgwater prayed for deliverance, the pestilence went on a rampage and killed at least twenty residents at a nearby manor.

To the north of Bristol, in Gloucester, anxious local officials ordered the town gate closed and all residents of the seaport banned from the town. But later in the fall, when the pestilence came up the road from Bristol—tired, hungry, and eager to get out of the rain—the quarantine proved as useless as it had been in Catania a year earlier. In 1350 someone scrawled Gloucester’s epithet on a church wall: “Miserable, wild, distracted. The dregs of the people alone survive.”

Sometime between November 1348 and January 1349, the Bristol prong of the pestilence—now thrusting inland on a road network that led eastward across the shires of south-central England to London—and the coastal prong—advancing northward from Dorset into the midlands—crossed paths.

As the plague pocket snapped shut, the blustery Bishop Ralph of Shrewsbury issued what would become one of the most famous pronouncements of the mortality. It was not quite Churchill’s we-will-fight-them-on-the-beaches speech, but Bishop Ralph, whose diocese of Bath and Wells lay trapped at the eastern edge of the plague pocket, was a master rhetorician himself. In January, when even the hopeful had lost hope, the bishop lifted hearts across the diocese with a startling announcement.

“Wishing, as is our duty, to provide for the salvation of souls and to bring back from their paths of error those who have wandered . . . [w]e declare that those who are now sick or should fall sick in the future . . . if they . . . cannot secure the services of a priest, then they should make a confession to each other as is permitted in the teachings of the apostles . . .”

A few paragraphs later, Ralph conferred another even more extraordinary right on the laity—or rather, on some of its members. The bishop said that if no priest could be found, “The Sacrament of the Eucharist [Holy Communion] . . . may be administered by a deacon [a layman who assists in ecclesiastical functions].”

The bishop’s extraordinary decision to give the faithful the right to administer the holy sacraments was born of desperation. The diocese of Bath and Wells would lose almost half its normal complement of priests in the mortality, and as Ralph’s proclamation noted, the dangers of ministering to the sick had become so great, no surviving priest could be found who was “willing whether out of zeal or devotion or for a stipend to take on the [duties of] pastoral care.”

Alas, the bishop’s personal courage did not quite measure up to his muscular rhetoric. In late January, as the plague danced through the streets of Bath, he retreated to the relative safety of his manor in rural Wiveliscombe. In fairness, it was Ralph’s normal practice to winter at the manor. Moreover, in 1349 he was hardly the only august personage to pay a prolonged visit to rural England. Edward III himself spent the early months of 1349 in the rural southeast and around Windsor—very fretfully, apparently, since he sent up to London for holy relics. Still, Ralph’s decision to leave Bath probably contributed to an ugly incident later in the year.

In December, as the plague was waning, he decided to visit the little town of Yeovil to celebrate a Mass of thanksgiving. However, after a year of “death and death and death,” the townspeople apparently became upset at the sight of the pink, plump Ralph riding into town at the head of a rather large and resplendent entourage. After the bishop disappeared inside the local church, an angry mob gathered in a nearby square. Voices were raised, fists waved, weapons brandished, denunciations made—then suddenly the crowd was running toward the church. Bishop Ralph’sRegister,a kind of official diary, describes the rest of the story. “Certain sons of perdition, [armed with] a multitude of bows, arrows, bars, stones and other kinds of arms” burst into the church, “fiercely wound[ing] very many . . . servants of God,” then “incarcerated [us] . . . in the rectory of said church until on the day following [the attack] the neighbors, devout sons of the church . . . delivered us . . . from our prison.”

On returning to Wiveliscombe, a very angry Ralph ordered Yeovil citizens Walter Shoubuggare, Richard Weston, Roger Le Taillour, and John Clerk—as well as other “sons of perdition”—excommunicated. The men were commanded to “go around the parish church . . . on Sundays and feast days . . . bare head[ed] and foot[ed] . . .” in a penitential manner. In addition, at High Mass, they had to hold a candle “of one pound of wax” until the hot wax had melted onto their hands. Perhaps the memory of the cemetery at Yeovil—“polluted by violent effusions of blood”—began to haunt the bishop, or perhaps he started to feel guilty about wintering in Wiveliscombe. Whatever the reason, soon after issuing the excommunication order, Ralph revoked it. “Lest . . . the teaching [of] Christ be diminished and the devotion . . . of God be weakened,” he wrote the vicar at Yeovil, “we suspend the said interdict.”

In Oxfordshire, the county to the east of Ralph’s diocese, the plague caused such devastation, the documents that survived have an end-of-the-world feel to them. In 1359 we hear that taxes can no longer be collected in the little hamlet of Tilgarsley because it has been deserted since 1350; in nearby Woodeaton manor, that after “the mortality of men . . . scarce two tenants remained . . . and they would have departed had not Brother Nicholas of Upton . . . made an agreement with them.” In Oxford, which lost three mayors to the plague, the few surviving documents include a petition from a university official and a death estimate. The official complains “that the university is ruined and enfeebled by the pestilence . . . so that its estate can hardly be maintained or protected.” The death estimate comes from a former chancellor, the fierce Richard Fitzralph, Bishop of Armagh. In 1357 the bishop wrote that there used to be “in ye University of Oxenford . . . thrilty thousand scolers [scholars] . . . and now [in 1357] there beth unneth [under] six thousand.” Since the town of Oxford itself, let alone the university, could not have held thirty thousand souls, the bishop was surely exaggerating. Nonetheless, what was true was that a great many people had died. The most trustworthy account of what happened in Oxford may come from an eighteenth-century scholar who says that when the plague arrived in the autumn of 1348, “those that had places and houses in the country retired [though overtaken there also] and those that were left behind were almost totally swept away. The school doors were shut, colleges and halls relinquished and none scarce left to keep possession or . . . to bury the dead.”

What such postmortems leave out are the details of daily life that autumn: the never-ending tattoo of rain on thatched roofs, the muffed thud of shovels in church graveyards, the lamentations of parentless children and childless parents, and, in the soggy fields beyond the little villages of southern England, the rotting carcasses of thousands of sheep and cows. Mass animal die-offs were common in the mortality, but, judging from contemporary accounts, in England they achieved a special intensity. “In the same year [as the pestilence],” wrote a chronicler, “there was a great sheep murrain [epidemic] throughout the realm, so much so that in one place five thousand sheep died in a single pasture, and the bodies were so corrupt that no animal or bird would touch them.”

The English animal die-offs seem to have been caused by rinderpest and liverfluke, herd diseases that flourish in damp weather. In 1348 and 1349, their spread was probably further abetted by a lack of shepherds to tend threatened flocks. However, in other places the die-offs may have been part of the pestilence. In Florence dogs, cats, chickens, and oxen died in the plague, and, like people, many had buboes. The most haunting report of an animal die-off comes from a medieval Arab historian, who says that in Uzbekistan lions, camels, wild boar, and hare “all lay dead in the fields afflicted with the boil.”

In England, as in other countries, one of the few things that offered a measure of protection against the pestilence was privilege. The stone houses of the wealthy were less vulnerable to rat infestation,* and the aristocracy and the gentry tended to enjoy better health in general. Indeed, most modern fifty-year-olds would envy the superb physicality of Bartholomew Burghersh, a knight and diplomat of Edward III’s time. When Burghersh died in late middle age, he still had a lean, muscular build, broad shoulders, a complete set of teeth, and no signs of osteoarthritis, a common feature of medieval skeletons. According to one estimate, only 27 percent of aristocratic and wealthy England died in the mortality, as opposed to 42 to 45 percent of the country’s parish priests, and 40 to 70 percent of the peasantry.

However, as a poem of the time noted, no one, not even the highborn, was immune from the universal pestilence.

Scepter and Crown

Must tumble down

And in the dust be equal made

With the poor crooked scythe and spade.

Southeast England, Early Fall 1348

Across the long quays of medieval Bordeaux flowed bales of wool, packets of produce, barrels of burgundy wine, and, on an early August day in 1348, a golden-haired princess of England, Joan Plantagenet, youngest child of Edward III. With her heart-shaped face and air of regal certitude, Joan must have seemed like a miracle to the weary French stevedores working the quays. For weeks they had known nothing but pestilential death; now, suddenly, here in their midst was a royal fairy tale, complete with four brightly pennoned English ships, a silky Spanish minstrel, a gift from Joan’s betrothed, Prince Pedro of Castile, a hundred regally dressed archers, and two of Edward’s most lofty servants, Andrew Ullford, leathery veteran of the French wars, and Robert Bourchier, lawyer and diplomat.

Little is known about the princess’s visit to Bordeaux except that she stopped there en route to Spain, where she was to marry Prince Pedro in the fall, and that the morning of her arrival the mayor, Raymond de Bisquale, was waiting on a quay to warn her and the rest of her wedding party about the presence of the plague. We also know that the English brushed aside the warning, though we do not know why. The princess’s foolishness can probably be attributed to her age. Fifteen-year-old royals must be even more inclined than ordinary fifteen-year-olds to think themselves immortal. However, the recklessness of the two senior figures in the royal party, Bourchier and Ullford, is harder to fathom. Perhaps after surviving Crécy, where the English had been outnumbered four or five to one, Ullford had developed his own delusions of immortality. Or maybe Mayor de Bisquale struck him and his fellow mandarin, Bourchier, as one of those inconsequential little Frenchmen with fussy hair and a funny walk.

The two royal officials should have known better.

On August 20 Ullford died a hard plague death, leavened only by a good view. The old soldier’s final hours were spent in the Château de l’Ombriere, a sumptuous Plantagenet castle overlooking Bordeaux harbor. Several others in the wedding party also died, including, on September 2, Princess Joan, who left behind the memory of a girlish laugh and an unworn wedding gown made from four hundred and fifty feet of rakematiz: a thick, rich silk embroidered with gold. What the princess did not leave behind was a body. In October Edward offered the Bishop of Carlisle a huge sum to go to pestilential Bordeaux and retrieve the princess’s corpse, but whether the prelate actually visited the town is unclear. In any case, Joan’s body was never recovered. Historian Norman Cantor thinks this is because her corpse was burned in October, when Mayor de Bisquale ordered the harbor set aflame. Intended to check the spread of the pestilence, the fire blazed out of control and destroyed several nearby buildings, including, notes Professor Cantor, Château de l’Ombriere, where Princess Joan died.

On September 15, when Edward III wrote to King Alfonso, Pedro’s father, to inform him of Joan’s death, the English demigod sounded like every parent who has ever tried to make sense of something as senseless as a child’s death. “No fellow human being could be surprised if we were inwardly desolated by the sting of grief, for we are human too. But we who have placed our trust in God . . . give thanks to Him that one of our own family, free of all stain, whom we have loved with pure love, has been sent ahead to heaven to reign among the choirs of virgins where she can gladly intercede for our offences before God.”

As Edward wrote, a new metastasis was developing in the south of England. During the fall, the plague appeared in Wiltshire, the county immediately to the east of Dorset, then, almost simultaneously, in Wiltshire’s eastern neighbors, Hampshire and Surrey. A circumstantial case can be made for Southampton, on the Wiltshire coast, as the source of the new outbreaks. Ships from France, including from Bordeaux, visited the port almost daily. However, since there were no telltale bursts of ecclesiastical death in Southampton until December, it also seems possible that this new assault by the plague originated in Dorset—perhaps from Melcombe,Y. pestisspread east as well as north.

All that can be said with certainty seven hundred years later is that in the fall of 1348, people in the counties to the east of Dorset knew that death was about to burst upon them. On October 24 Bishop William Edendon, whose Hampshire diocese of Winchester stood directly in harm’s way, issued an ominous warning. Evoking the lamentations of Rachel in Matthew 2:18,* the bishop declared, “A voice has been heard in Rama. . . . We report with anguish the serious news . . . that this cruel plague has begun a . . . savage attack on the coastal area of England. . . . We are struck with terror lest . . . this brutal disease should rage in any part of our city or diocese.”

On November 17, with the plague now howling at Hampshire’s borders, Bishop Edendon took the occasion to remind the faithful of “the radiant eternal light which glows . . . in the dark core of human suffering.” In a second proclamation, the bishop declared that while “sickness and premature death often come from sin . . . by the healing of souls this kind of sickness [the plague] is known to cease.” There is no record of how many of the faithful drew hope from the bishop’s words.

Like Tolstoy’s unhappy families, over the first winter of the pestilence, the little towns of southern England began to die, each in its own way. The following May, as a spring sun warmed the gray slabs of Stonehenge, the only sound to be heard on the nearby Wiltshire estate of Carleton Manor was birdsong. Carleton’s water mills stood quiet, its farmlands untilled, and twelve of its thatched cottages empty. The years 1348 and 1349 may have been the quietest years in the English countryside since the land was first inhabited by man. At Ivychurch priory, near the Wiltshire-Hampshire border, twelve of the priory’s thirteen canons lay dead. One can scarcely imagine the feelings of the survivor, James de Grundwell, but by March l349 he must have found it odd not to wake to the sound of rain pounding against the roof and the moans of dying monks echoing through the dank monastery halls. Edward thought de Grundwell’s good fortune worthy of both a promotion and a mention in a royal dispatch. “Know ye that since . . . all the other canons of the same house, in which hitherto there had been a community of thirteen canons regular, have died . . . , we appoint James de Grundwell custodian of the possessions, the Bishop testifying that he is a fit and proper.”

In Winchester, ancient capital of England, an all-too-familiar problem produced a bitter division in January 1349. Concerned about unburied corpses “infecting” the air—and hence spreading the pestilence—the laity wanted to dig a plague pit outside the city; but the clerical establishment, led by Bishop Edendon, resisted. The plague pit would be on unconsecrated ground, and people buried on such ground might be overlooked on Resurrection Day. On January 19 Bishop Edendon tried to mollify popular discontent about the Church’s stance on burials with another proclamation. There was good news, the bishop declared. “[T]he Supreme pontiff . . . had . . . on account of the imminent great mortality, granted to all people of the diocese . . . a plenary indulgence at the hour of death if they departed in good faith.” However, with piles of unburied bodies everywhere, secular Winchester had become impatient with religious bromides. A few days after the bishop’s announcement, anger about the plague pit boiled over into violence. A group of townsfolk attacked a monk while he was saying a funeral Mass.

After the attack, the Church bowed to popular will and ordered the town’s existing cemeteries expanded and new burial sites dug in the countryside. However, Bishop Edendon, who had one of those minds that have kept the Catholic Church in business for the last two thousand years, was not about to let the townspeople have the last word in the dispute. As part of the cemetery expansion, he announced that a plot of diocese land used by local merchants as a market and fairgrounds for over a century would be converted into a burial site. For good measure, the bishop also had the town of Winchester fined forty pounds for encroaching on diocese property.

Over the winter of 1348–49, as “every joy . . . ceased . . . and every note of gladness . . . hushed,” perhaps half of Winchester died. The diocese, which included the neighboring county of Surrey, had one of the highest clerical mortality rates in England; 48.8 percent of the beneficed—or salaried—clergy in the diocese perished. Figures for the town of Winchester are less precise, but by 1377 a preplague population of eight thousand to ten thousand had shrunk to a little more than two thousand. Not all the missing eight thousand townspeople were plague fatalities, but one historian thinks a death figure of four thousand for Winchester is “conservative.” Other parts of Hampshire county also became “abodes of horror and a very wilderness” over the first winter of the pestilence. In Crawley the plague carried off so many people, the village did not attain its preplague population of 400 again until 1851, five centuries later.

At Southampton, where the Italians came to buy English wool and the French to deliver wine, contemporary records indicate that as much as 66 percent of the beneficed clergy may have died in the first winter of the plague. Hayling Island, near Portsmouth, also suffered grievously. “Since the greater part of the . . . population died whilst the plague was raging,” Edward III declared in 1352, “. . . the inhabitants are oppressed and daily are falling most miserably into greater poverty.”

While some villages vanished entirely during the Black Death, one of the great English legends—that hundreds of villages were obliterated in the pestilence—has turned out to be partially myth. Recent research indicates that many of the “lost” villages actually succumbed to economic atherosclerosis; others, though given a final nudge into oblivion by the mortality, were already so weak economically, death was inevitable. However, the legend of the lost plague villages is not entirely untrue. Here and there in the green and pleasant English countryside, one comes across the odd ruin—the crumbling wall or overgrown path—that still echoes of the time when, everywhere upon the land, there was “death without sorrow, marriage without affection, want without poverty and flight without escape.”

Undoubtedly, the average Englishman found the mortality as frightening as the average Florentine or Parisian, but a phlegmatic, self-contained streak in the English character kept outbursts like those at Winchester and Yeovil and quarantines like those at Gloucester relatively infrequent. For every English “son of perdition” overcome by fear, there were a dozen John Ronewyks: solid, undemonstrative men who ignored the danger and quietly went about their work. As one English historian has observed, “With his friends and relations dying in droves, . . . with every kind of human intercourse rendered perilous by the possibility of infection, the medieval Englishman obstinately carried on in his wonted way.”

Ronewyk was reeve—or manager—at the Hundred of Farnham, one of more than forty manors owned by Bishop Edendon’s diocese of Winchester. Little is known about John’s personal life, but from contemporary documents we can piece together an idea of how he sounded and looked. Like modern German or Spanish speakers, medieval Englishmen pronounced their long vowels, so when John told the dairymaid at Farnham, “I have a liking for the moon,” he would have said, “I hava leaking for the moan.” John also would have been a pretty unprepossessing dresser; his wardrobe probably consisted of one copy of four basic items—breeches (underwear), hose, a shirt, and a kirtle, an all-purpose overgarment. On nights when he was planning a visit to the dairymaid, John’s mother would have ironed his single shirt with a “sleek stone,” a heavy, flat-sided object that she would warm by the fire first. Like many of his contemporaries, John probably slept naked. This common medieval habit must have made the work ofX. cheopis,the rat flea, andP. irritans,the human flea, a good deal easier.

Farnham, the estate that John managed, was located in Britain’s Champion country. The region, which stretches from southern Scotland to southern England, is one of most fertile areas in the world. Only the Ukraine and parts of western Canada and the United States have the same combination of good soil and clement weather. Today much of Champion country is buried under high streets and mini-marts, but in John’s time, the region was a vast golden sea of wheat and barley, interspersed with neat rows of trees and picturesque little villages of thirty to forty families. Each house was built almost exactly like its neighbor—thatched roof, timber frame, and walls made from wattle and daub—and each village was its own little island world in the vast, swaying grain sea.

In the summer of 1347—the summer before the plague—life in Farnham was better than it had been in decades. Bishop Edendon might have been an irascible character, but in the fourteenth century his well-managed estates were among the few places in England where crop yields were approaching thirteenth-century levels again. There was also more fresh meat and ale on village tables, and many of the vexatious old feudal obligations were beginning to disappear. In a way, 1066 was even being avenged. As mid-century approached, vernacular English, the language of ordinary folk like John, was replacing French, the language spoken by the Norman conquerors of 1066, and the official language of the English aristocracy and government. In the fourteenth century the scholar John Trevisa remarked that, these days, English aristocrats, many of Norman blood, knew “no more French than their left heel.”

With several thousand acres and three to four thousand souls under his care, John Ronewyk was, in effect, managing a good-sized agribusiness. An eleventh-century book calledGerefalists a reeve’s principal duties as agricultural management and estate maintenance, but a man like John was also expected to know how everything worked on the manor and to help collect the rents, taxes, and fees due the lord. However,Gerefahad nothing to say about the problems that John began to encounter in the autumn of 1348, when the pestilence arrived at Farnham.

The timing ofY. pestis’s appearance is interesting. Farnham lies to the east of Dorset and Wiltshire, near the border between Hampshire and Surrey, yet the manor recorded its first plague deaths around the same time as these more westerly counties. The timing raises two possibilities; either Surrey was infected independently—possibly by sea—or else contemporaries like Bishop Edendon underestimated how quickly the plague spread along the coast. On October 24, while the bishop was issuing his “Rama” warning in Winchester, about twenty-five to thirty miles to theeast,Farnham already had or was about to have its first two plague cases. The manor rolls for 1348 show that two tenants died in October. In November there were three more deaths, and in December, eight. In January the death toll fell to three, and in February to one. The combination of rain, cold weather, and the rapid dash along the wintry English coast had leftY. pestiswinded. In June the mortality rate was still holding at one death per month, but then, in midsummer, when the fields were gold with wheat and the manor barns echoed with buzzing flies,Y. pestisrevived. As July turned into August, “People who one day had been full of happiness, were the next found dead.”

From the fall of 1348 to the fall of 1349, the first year of the pestilence, 740 people died at Farnham—a mortality rate of about 20 percent. As the second winter approached, people no doubt hoped for another reprieve, but this time, energized by the fresh summer air and country sun, the pestilence continued its killing ways through the cold weather. From the fall of 1349 to the fall of 1350, an additional 400-plus residents died. By the timeY. pestisfinally left Farnham in early 1351, the mortality had claimed almost fourteen hundred people at the manor. Since we have only a rough estimate of Farnham’s population, it is difficult to arrive at a percentage figure, but one scholar who examined the rolls estimates that more than a third and perhaps as much as a half of the manor died.

In many other parts of Europe, death on so vast a scale led to great chaos and social dislocation. But except for the wailing that echoed through the manor villages on soft summer nights and the number of people who wore black to church on Sundays, outwardly life at Farnham seemed to change very little. During the first year of the pestilence, the crops were harvested on time and in the usual amounts—Bishop Edendon’s castle received its annual set of repairs, and the ponds got their annual refurbishment. John’s friend, the dairymaid, even made her usual six cloves of butter (a clove equals seven to eight pounds); and after the harvest, the fortunate haymakers received a bonus of four bushels and four quarters of oats. At Christmastime the staff at the bishop’s castle were feted with their traditional three holiday dinners.

Over the winter of 1348–49 Farnham experienced its first plague-related economic dislocations. As manpower shortages developed, labor costs exploded, while the price of farm animals plummeted. “A man could have a horse previously valued at forty shillings for half a mark, a good fat ox for four shillings, and a cow for 12 quid,” wrote a contemporary. The sharp drop in animal prices was rooted in a provision of feudal law that came back to haunt estate owners during the pestilence. When a tenant died, the lord of the manor was entitled to the dead man’s best beast of burden as a death tax. Usually the heriot, as the tax was called, was a boon for the lords, but so many peasants were dying in the winter of 1348–49, estates had more animals than they knew what to do with. John, a shrewd manager, decided to hold on to most of the livestock that had come into Bishop Edendon’s possesion until prices firmed up, but he was the exception. At most manors, “heriot” animals were dumped onto the market, depressing prices.

Thanks to John’s prudence and firm leadership, Farnham prospered during the first year of the plague. Receipts amounted to 305 pounds, while working expenses were only about 43 pounds.

The second year was harder. Death had become so pervasive, whole families were being obliterated now. Forty times that second year, the name of a deceased tenant was read aloud in manor court, and forty times no blood relation came forward to claim his vacant holding. As the “harshness of the days stiffen[ed] men’s malice,” the surviving tenants, John included, began to work two farms, their own and a dead neighbor’s. In a time of death without end, marriage all but vanished. In 1349 there were only four weddings at Farnham.

In 1350 John Ronewyk had less of everything—money, good weather, and labor, which had now become ruinously expensive and very surly. “No workman or laborer was prepared to take orders from anyone whether equal, inferior or superior,” wrote a chronicler. Despite obstacles unimaginable to the author of Gerefa, in 1350, as in the previous years, John got the crops in on time. In the third year of the pestilence, the harvest was less than it had been in 1349, but not substantially less. In 1350 John’s friend, the dairymaid, even made her usual number of cheeses—26 in winter and 142 during the summer—and butter: eight cloves, or roughly fifty pounds.

Bishop Edendon must have marveled at John’s ingenuity. In the midst of one of the bleakest years in all of English history, he organized a small army of tillers, masons, plumbers, carpenters, sawyers, and quarrymen. In l350 the bishop’s manor at Farnham got more than its usual annual refurbishment. Somehow John found the princely sum of twenty-two shillings and five quid to pay the workmen’s inflated wages.

Social cohesion is a complex phenomenon, but applied gently—with a respect for the vast differences in time and place—the Broken Windows theory of human behavior may speak to the relatively low level of upheaval in Black Death England.

The theory, which informs much modern police work, holds that the physical environment buttresses the psychological environment the way a beam buttresses a roof. Why? Broken windows, dirty streets, abandoned cars, boarded-up storefronts, empty grass- and refuse-covered lots send the message: “No one is in charge here.” And when authority and leadership break down, people become more prone to lawlessness, violence, and despair, in the same way that a defeated army becomes more prone to panic if the officers fail to provide resolute leadership.

England in 1348 and 1349 was hardly free of physical or emotional chaos, but enough John Ronewyks stepped forward—to harvest the crops, maintain the land and buildings, keep the records, man the courts—to convey the sense that the country was not slipping into anarchy, that authority was being maintained. Their steady leadership may have helped to sustain order, self-discipline, and lawfulness at a very difficult moment.

Excerpt from The Great Mortality: An Intimate History of the Black Death (Chapter 8), by John Kelly (Harper, 2005), published under fair use for educational purposes.