In antiquity and through the Middle Ages, the concept of temperature was quite different from today.

By Mark Cartwright

Historian

Introduction

The thermometer was invented in the mid-17th century during the Scientific Revolution when scientists began to search for an accurate instrument to measure a wide range of temperatures using a scale that could be compared with other readings taken by other scientists elsewhere. First air and then expanding liquids like alcohol and mercury were used to create a fine instrument that opened up new possibilities of knowledge in many fields, but especially chemistry and medicine.

Thermoscopes

In antiquity and through the Middle Ages, the concept of temperature was quite different from today. Temperature, because it could only be measured by the feel of the body, was thought of as a vague ‘hot’ and ‘cold’, with the two recognised extremes being ice and boiling water. The great ancient physician Galen (129-216 CE), for example, only had four grades of temperature based on these two extremes. Galen’s method of ascertaining a patient’s temperature was similarly vague. The doctor held the patient’s hand, and if it felt hotter than his, then the patient was ‘hot’, if it was cooler, then he was ‘cold’, and so, in either case, the person was ill. This idea endured for centuries. The concept of measuring temperature in small degrees on a scale had to wait until the 17th century when it finally seized the imagination of scientists and inventors.

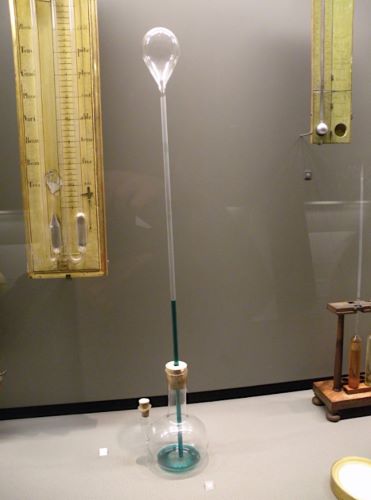

The first early modern thermometers were of the thermoscope type. This design of thermometer consisted of a narrow tube filled with water which moves up (or down) a scale when air below (or above) it is heated and so expands, pushing up (or down) the liquid. The Italian all-round genius Galileo (1564-1642) is often credited with the invention of the thermoscope, but the evidence is hardly conclusive. It is true that it was Galileo’s friend Santorio Santorio (1561-1636) who first used the thermoscope type of thermometer in the field of medicine, Santorio then being professor of medicine at the prestigious and influential University of Padua. Although Galileo himself claimed to be its inventor, as the historians L. Fermi and G. Bernardini note, “the thermometer seems to have been invented independently by several people at different places” (31). Other scientists often put forward as the possible inventors of the thermoscope include Cornelius Drebbel (1572-1633) in the Netherlands and Robert Fludd (1574-1637) in England.

Santorio provides the first mention in writing of the thermoscope in his 1612 work Commentary on the Medical Art of Galen. The thermoscope was a good start to the problem of measuring temperatures, but it was a clumsy instrument that could not take very precise readings. Another major disadvantage was that it gave undesirable variations depending on the surrounding air pressure. Otto von Guericke (1602-1686) did make tangible improvements to the thermoscope, but a more precise and less cumbersome device was needed for practical daily use and collaborative scientific research.

The First Thermometers

The key to finding the secret of accurate temperature measurement was found in Italy. Grand Duke Ferdinand II of Tuscany (r. 1621-1670) was keenly interested in science, and he founded the learned Academia del Cimento in the city of Florence. Here, around 1650, the idea of using a liquid that itself expands rather than the air in the thermometer tube was developed. The first models used alcohol in a sealed and very thin glass tube. In order to take the readings on the provided scale more easily, the alcohol was coloured. This instrument became known as a Florentine thermometer and replaced the thermoscope type by the end of the 17th century. The Florentine scientists had made experiments with mercury instead of alcohol but went for the latter because it is more sensitive to temperature change. The drawbacks of alcohol were that in the 17th century, it was not so easy to acquire absolutely pure alcohol and that it had a low boiling point. These two negatives meant that the thermometers of the day were not always as accurate as might have been hoped for by their users, and, certainly, it was difficult to compare more precise readings between different thermometers.

Despite the early problems, the thermometer was an important part of the Scientific Revolution. Held back for centuries by Aristotelian natural philosophy and its suspicion of anything other than the senses to understand the world, for the first time, scientists combined their studies, intelligence, and sense-improving instruments to make real progress in knowledge. As the Scientific Revolution progressed, instruments like the thermometer, telescope, and microscope were no longer being used to prove existing theories of knowledge were correct but to discover entirely new areas of knowledge. Another distinct feature of the Scientific Revolution was the collaboration between scientists across different countries. The pressing problem now, then, was getting everyone to agree on a universal scale to measure temperature.

Matters of Scale

Having perfected a reasonably accurate and inexpensive instrument for measuring temperature, the ideal of a universal scale so that readings could be easily compared between devices wherever they might be used proved elusive. By the early 18th century, there was still no standard scale of measurement for thermometers, and it was not uncommon for a single thermometer to have two or even three scales on it. The famed physicist, chemist, and dabbler in alchemy Robert Boyle (1627-1691) had pushed for a standardised scale, although his suggestion that the freezing point of aniseed oil be used as the base marker never caught on. There had also been some efforts by institutions to have experiments conducted using only standardised instruments. For example, the Royal Society in London and the Academia del Cimento in Florence had collaborated to make sure all their projects used the same type of thermometer and scale. In this way, the results of the research could be compared regardless of by whom and where the readings were taken.

There was still the prevailing idea that, to paraphrase the Greek philosopher Protagoras (c. 485-415 BCE), ‘Man is the measure of all things’, and so markers of the temperature scale were often made in reference to the human body. In 1701, Isaac Newton (1642-1727) considered the temperature of human blood as a good point zero for a temperature scale. In a similar vein, Newton’s contemporary John Fowler wanted to use as his marker for the top of the temperature scale the maximum heated liquid the human hand could bear without pulling away.

In the end, there would be two clear winners in a field of some 35 competing temperature scales. The German Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit (1686-1736) devised his scale around 1714, using two phenomena: the melting of ice to water and the normal body temperature of a human being. These were 32 and 96 respectively on the Fahrenheit scale, with each number in-between being called a degree. The Fahrenheit scale went as high as boiling water – 212 degrees Fahrenheit. Fahrenheit thermometers were widely adopted in England and the Netherlands, but there was one serious and enduring competitor.

The second big winner in the temperature scale wars was Anders Celsius (1701-1744) from Sweden. Celsius came up with his centigrade scale which went from 0 (the freezing point of water) to 100 (the boiling point of water). The scale remains, of course, popular today since it eventually replaced the Fahrenheit scale in most countries, with the notable exception of the United States and a few other states.

Additional scales of temperature did come along later, notably, in 1848, the Kelvin scale devised by the British scientist William Thomson (1824-1907) – the name derives from his title Lord Kelvin. The Kelvin scale uses the Celsius scale, but keyed to absolute zero, the coldest possible temperature. The Fahrenheit scale received the same conversion, with the Rankine scale devised by the Scotsman William Rankine (1820-1872).

New Innovations

It was Fahrenheit who invented the mercury thermometer around 1714. This type could measure a wider range of temperatures compared to the alcohol thermometer. The ‘air’ inside the thermometer was another consideration that would improve accuracy and for this reason, the much more sensitive nitrogen or argon gasses came to be used inside the glass tube.

Such a useful instrument for science as the thermometer soon got scientists pondering how to independently measure the accuracy of any single instrument. The French scientists J. A. Deluc (1727-1817) and Antoine Lavoisier (1743-1794) conducted a great number of experiments in this area, as did English scientists. As a result, “by the 1770s French and English instrument makers built thermometers accurate to 1/10 degree” (Bynum, 420).

Finally, the accurately tested thermometer which used an internationally recognised scale was available to all. Doctors, for example, could now use the thermometer to make a more accurate diagnosis of their patient’s ailment and track its progress with greater care. Chemists could conduct experiments and record their findings, which could then be communicated to others who knew that the precise temperatures involved could now be replicated in their own laboratories.

By the end of the 18th century, thermometers were being made which could record the lowest and highest temperatures in a given period. This was done by inserting a small spring inside the thermometer’s tubes which was pushed up or down by the movement of the mercury but then stayed in position when the temperature changed again and the mercury retracted. In 1860, William Siemans (1823-1883) developed the electrical resistance thermometer. Here the principle is that, as a metal changes temperature, so its electrical resistance also changes. This type of thermometer was improved further by Hugh Callendar (1863-1930) around 1890.

Modern Thermometers

By the early 20th century, a doctor could consult a ready-made chart which told them the expected temperature changes seen during the span of certain illnesses. Chemists could also use such charts in reference to specific materials and experiments. Of course, thermometers kept on evolving, too. Toxic mercury was always a problem if the thermometer was accidentally broken, and so it has been replaced by safer metal alloys. In the 21st century, scientists use thermometers containing a material like platinum which can be used to minutely measure electrical resistance or thermometers that use infra-red light, sound, magnetism, or the expansion of tiny metal strips to take a reading over a much broader range of temperatures than the liquid thermometer is capable of. In many home medicine cabinets today, the liquid thermometer has been replaced by the electronic thermometer fitted with a thermistor that gives a precise digital reading. Nowadays, all manner of objects benefit from in-built thermometers which make them temperature sensitive, devices which range from household heating systems to security cameras.

Bibliography

- Burns, William E. The Scientific Revolution. ABC-CLIO, 2001.

- Bynum, William F. & Browne, Janet & Porter, Roy. Dictionary of the History of Science. Princeton University Press, 1982.

- Fermi, Laura & Bernardini, Gilberto. Galileo and the Scientific Revolution. Dover Publications, 2013.

- Wootton, David. The Invention of Science. Harper, 2015.

Originally published by the World History Encyclopedia, 09.01.2023, under a Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.