Ancient education was never monolithic. It reflected and reproduced the inequalities of its time, yet it also allowed for moments of permeability.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Education in antiquity was never a neutral enterprise. Its structures reflected the hierarchies, anxieties, and aspirations of the societies that shaped it. While often idealized by later historians as the cradle of reason or civic virtue, ancient education was deeply stratified along the lines of class, gender, ethnicity, and cultural identity.

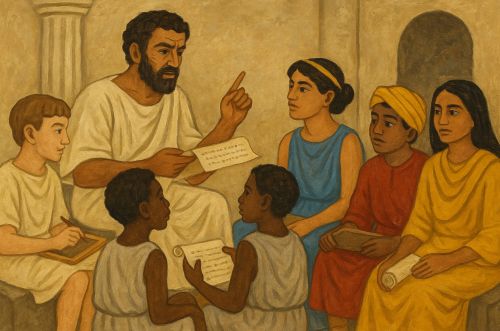

To explore education in Athens, Rome, Alexandria, or the academies of the Near East is to witness not only the training of elites but also the marginalization and occasional integration of those excluded from power. This essay examines the complex dynamics of diversity in ancient education, with particular attention to social class and access, the role of women, cultural pluralism among students, the question of race, and the less visible but equally significant question of gender identities beyond the male-female binary.

Education and Social Class

Access to education in the ancient world was overwhelmingly determined by class. In classical Athens, the sons of citizens were taught grammar, rhetoric, and music, disciplines intended to prepare them for civic participation.1 Education was both a mark of status and a gatekeeping mechanism. Those outside the citizen class (slaves, metics (resident foreigners), and the poor) were largely excluded from formal schooling. Yet there were exceptions: wealthier metics might hire private tutors, and enslaved boys of exceptional talent were sometimes trained for use as scribes or tutors themselves.2

Rome inherited and adapted these practices. The Roman ludi litterarii, primary schools for boys, were technically open to a broad swath of the population, but literacy rates remained closely tied to wealth.3 The education of aristocrats focused on rhetoric, essential for political life, while poorer citizens often received only rudimentary training, if any. In Egypt and Mesopotamia, scribal schools functioned as elite institutions. The training in cuneiform or hieroglyphics required years of specialization, effectively barring most of the population.4 Education thus reinforced class boundaries, privileging those with resources while presenting literacy itself as a badge of power.

Women and Education

The question of women’s education reveals a complicated tension between ideology and practice. Greek authors frequently mocked or dismissed the idea of female intellectual development. Aristotle famously declared women naturally inferior, unfit for higher reasoning.5 Yet archaeological and textual evidence suggests that women, particularly in elite households, were often literate. In Hellenistic Egypt, papyri preserve women’s letters written in their own hand, attesting to a level of education inconsistent with philosophical prejudices.6

In Rome, wealthy women received private instruction, particularly in grammar and philosophy, as a way to prepare them for household management and public presentation. Cornelia, the mother of the Gracchi brothers, was praised for her literary culture.7 Stoic philosophers like Musonius Rufus went further, explicitly arguing for the education of women in philosophy on the grounds that virtue is not gendered.8 Despite such arguments, women’s access to education was precarious and often justified only within domestic or moral frameworks. Still, their presence as literate actors complicates any easy narrative of exclusion.

Cultural and Linguistic Diversity

The multicultural reality of the ancient Mediterranean profoundly shaped educational spaces. Alexandria, with its vast libraries and polyglot population, became a hub of intellectual exchange. Greek served as the lingua franca of elite scholarship, but Egyptian priests continued to train scribes in hieroglyphics, while Jewish communities maintained schools for teaching Hebrew scripture.9 This coexistence created both opportunities and tensions: while Hellenization facilitated access to wider intellectual currents, it also marginalized indigenous languages and traditions.

Roman education further illustrates this pluralism. Elite Roman students studied Greek as a mark of cultivation, often under Greek tutors, while Latin became the medium of law and administration.10 Students in provincial contexts faced the challenge of navigating multiple linguistic worlds. In Gaul or North Africa, local languages persisted alongside Latin instruction, creating classrooms where diversity of tongue was a daily reality.11

Religious diversity was likewise present. Jewish students in the Roman East received training in both Torah and Greek philosophy, while early Christian catechetical schools in Alexandria sought to integrate scriptural study with Platonic thought.12 Education thus functioned as a site of cultural negotiation, simultaneously reinforcing imperial hierarchies and enabling hybrid intellectual identities.

Race and the Ancient Classroom

The concept of race in antiquity does not map neatly onto modern categories. While ancient texts recognize differences in skin color, hair, and physiognomy, these distinctions were generally subordinated to cultural or geographic identity.13 Education in Greece and Rome was more likely to discriminate on the basis of status (free or enslaved) than on phenotype. Nevertheless, African and Near Eastern students are attested in Mediterranean schools. The philosopher Plotinus, born in Egypt, studied in Alexandria before teaching in Rome, where his origin was never considered a barrier to intellectual legitimacy.14

At the same time, biases persisted. Greek authors often associated “barbarians” with inferior reasoning, and Roman writers mocked provincial accents.15 These prejudices remind us that even where access was possible, students from non-Greek or non-Roman backgrounds carried cultural burdens within educational institutions.

Gender Beyond the Binary

While rarely discussed in standard accounts of ancient education, gender diversity beyond the male-female binary deserves consideration. Ancient societies recognized categories of gender variance, though not in modern terms. In Mesopotamian texts, the gala priests, male-born individuals who took on feminine roles, were trained in ritual lamentation and song, an education that was both specialized and highly respected.16 In Rome, the galli, priests of Cybele, were often castrated and adopted feminine dress; their initiation involved forms of training that blurred distinctions of gendered education.17

Though marginalized socially, these figures demonstrate that education was not restricted to a binary conception of gender roles. Their training highlights the diversity of paths available to those who transgressed conventional categories, and it complicates any assumption that ancient education was exclusively heteronormative or patriarchal.

Margins and Informal Education

Beyond formal schools, diverse populations accessed education through informal means. Enslaved people often acquired skills through apprenticeship, learning not in classrooms but in households, workshops, or temples. Women, excluded from formal institutions, might be educated within domestic spaces, passing knowledge through maternal teaching. Merchants and travelers gained linguistic fluency through trade, acquiring what might be called “vernacular educations” that proved as useful as the polished rhetoric of aristocrats.18

These alternative educational trajectories suggest a spectrum of literacies, where access to knowledge was more varied than elite sources imply. Diversity thus emerges not only from those who entered formal schools but also from those who pursued learning outside their boundaries.

Conclusion

Ancient education was never monolithic. It reflected and reproduced the inequalities of its time, yet it also allowed for moments of permeability, where women, foreigners, enslaved persons, and gender-variant individuals found entry points into intellectual culture. To speak of diversity in ancient education is to speak of tension, between exclusion and inclusion, hierarchy and hybridity, silence and voice. The classroom of antiquity was a microcosm of its society, revealing not only what knowledge was valued but also who was considered worthy of receiving it.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Aristotle, Politics.

- Raffaella Cribiore, Gymnastics of the Mind: Greek Education in Hellenistic and Roman Egypt (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001).

- William V. Harris, Ancient Literacy (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1989).

- Joshua J. Mark, “Mesopotamian Education,” March 27, 2023, https://www.worldhistory.org/article/2203/mesopotamian-education/.

- Aristotle, Politics, bk. 1.

- Raffaella Cribiore, “School Structures, Apparatus, and Materials,” in A Companion to Ancient Education, ed. W. Martin Bloomer (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2015), 152.

- Jo-Ann Shelton, As the Romans Did: A Sourcebook in Roman Social History, 2nd ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998).

- Musonius Rufus, Lectures.

- Too, Yun Lee, ed., Education in Greek and Roman Antiquity (Leiden: Brill, 2001).

- Harris, Ancient Literacy.

- Vandorpe, “Education in Hellenistic and Roman Egypt.”

- Too, Education in Greek and Roman Antiquity.

- Craig A. Williams, Roman Homosexuality, 2nd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010).

- Plotinus, Enneads.

- Too, Education in Greek and Roman Antiquity.

- John J. Winkler, ed., Before Sexuality: The Construction of Erotic Experience in the Ancient Greek World (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991).

- Williams, Roman Homosexuality.

- Cribiore, Gymnastics of the Mind.

Bibliography

- Aristotle. Politics.

- Cribiore, Raffaella. Gymnastics of the Mind: Greek Education in Hellenistic and Roman Egypt. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001.

- Cribiore, Raffaella. “School Structures, Apparatus, and Materials.” In A Companion to Ancient Education, edited by W. Martin Bloomer, 149-159. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2015.

- Harris, William V. Ancient Literacy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1989.

- Musonius Rufus. Lectures.

- Plotinus. Enneads.

- Mark, Joshua J. “Mesopotamian Education.” March 27, 2023. https://www.worldhistory.org/article/2203/mesopotamian-education/.

- Shelton, Jo-Ann. As the Romans Did: A Sourcebook in Roman Social History. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

- Too, Yun Lee, ed. Education in Greek and Roman Antiquity. Leiden: Brill, 2001.

- Williams, Craig A. Roman Homosexuality. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Winkler, John J., ed. Before Sexuality: The Construction of Erotic Experience in the Ancient Greek World. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991.

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.21.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.