The virus mutates slightly in a process called antigenic drift.

By Dr. Alexandra M. Lord

Chair and Curator of Medicine and Science

Smithsonian Institution

Introduction

In recent months, Americans looking for eggs have faced empty shelves in their grocery stores. The escalating threat of avian flu has forced farmers to kill millions of chickens to prevent its spread.

Nearly 70 years ago, Maurice Hilleman, an expert in influenza, also worried about finding eggs. Hilleman, however, needed eggs not for his breakfast, but to make the vaccines that were key to stopping a potential influenza pandemic.

Hilleman was born a year after the notorious 1918 influenza pandemic swept the world, killing 20 million to 100 million people. By 1957, when Hilleman began worrying about the egg supply, scientists had a significantly more sophisticated understanding of influenza than they had previously. This knowledge led them to fear that a pandemic similar to that of 1918 could easily erupt, killing millions again.

As a historian of medicine, I have always been fascinated by the key moments that halt an epidemic. Studying these moments provides some insight into how and why one outbreak may become a deadly pandemic, while another does not.

Anticipating a Pandemic

Influenza is one of the most unpredictable of diseases. Each year, the virus mutates slightly in a process called antigenic drift. The greater the mutation, the less likely that your immune system will recognize and fight back against the disease.

Every now and then, the virus changes dramatically in a process called antigenic shift. When this occurs, people become even less immune, and the likelihood of disease spread dramatically increases. Hilleman knew that it was just a matter of time before the influenza virus shifted and caused a pandemic similar to the one in 1918. Exactly when that shift would occur was anyone’s guess.

In April 1957, Hilleman opened his newspaper and saw an article about “glassy-eyed” patients overwhelming clinics in Hong Kong.

The article was just eight sentences long. But Hilleman needed only the four words of the headline to become alarmed: “Hong Kong Battling Influenza.”

Within a month of learning about Hong Kong’s influenza epidemic, Hilleman had requested, obtained and tested a sample of the virus from colleagues in Asia. By May, Hilleman and his colleagues knew that Americans lacked immunity against this new version of the virus. A potential pandemic loomed.

Getting to Know Influenza

During the 1920s and 1930s, the American government had poured millions of dollars into influenza research. By 1944, scientists not only understood that influenza was caused by a shape-shifting virus – something they had not known in 1918 – but they had also developed a vaccine.

Antigenic drift rendered this vaccine ineffective in the 1946 flu season. Unlike the polio or smallpox vaccine, which could be administered once for lifelong protection, the influenza vaccine needed to be continually updated to be effective against an ever-changing virus.

However, Americans were not accustomed to the idea of signing up for a yearly flu shot. In fact, they were not accustomed to signing up for a flu shot, period. After seeing the devastating impact of the 1918 pandemic on the nation’s soldiers and sailors, officials prioritized protecting the military from influenza. During and after World War II, the government used the influenza vaccine for the military, not the general public.

Stopping a Pandemic

In the spring of 1957, the government called for vaccine manufacturers to accelerate production of a new influenza vaccine for all Americans.

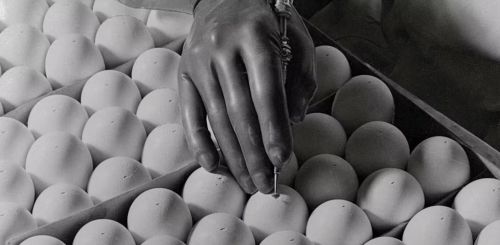

Traditionally, farmers have often culled roosters and unwanted chickens to keep their costs low. Hilleman, however, asked farmers to not cull their roosters, because vaccine manufacturers would need a huge supply of eggs to produce the vaccine before the virus fully hit the United States.

But in early June, the virus was already circulating in the U.S. The good news was that the new virus was not the killer its 1918 predecessor had been.

Hoping to create an “alert but not an alarmed public,” Surgeon General Leroy Burney and other experts discussed influenza and the need for vaccination in a widely distributed television show. The government also created short public service announcements and worked with local health organizations to encourage vaccination.

Vaccination rates were, however, only “moderate” – not because Americans saw vaccination as problematic, but because they did not see influenza as a threat. Nearly 40 years had dulled memories of the 1918 pandemic, while the development of antibiotics had lessened the threat of the deadly pneumonia that can accompany influenza.

Learning from a Lucky Reprieve

If death and devastation defined the 1918 pandemic, luck defined the 1957 pandemic.

It was luck that Hilleman saw an article about rising rates of influenza in Asia in the popular press. It was luck that Hilleman made an early call to increase production of fertilized eggs. And it was luck that the 1957 virus did not mirror its 1918 relative’s ability to kill.

Recognizing that they had dodged a bullet in 1957, public health experts intensified their monitoring of the influenza virus during the 1960s. They also worked to improve influenza vaccines and to promote yearly vaccination. Multiple factors, such as the development of the polio vaccine as well as a growing recognition of the role vaccines played in controlling diseases, shaped the creation of an immunization-focused bureaucracy in the federal government during the 1960s.

Over the past 60 years, the influenza virus has continued to drift and shift. In 1968, a shift once again caused a pandemic. In 1976 and 2009, concerns that the virus had shifted led to fears that a new pandemic loomed. But Americans were lucky once again.

Today, few Americans remember the 1957 pandemic – the one that sputtered out before it did real damage. Yet that event left a lasting legacy in how public health experts think about and plan for future outbreaks. Assuming that the U.S. uses the medical and public health advances at its disposal, Americans are now more prepared for an influenza pandemic than our ancestors were in 1918 and in 1957.

But the virus’s unpredictability makes it impossible to know even today how it will mutate and when a pandemic will emerge.

Originally published by The Conversation, 02.06.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution/No derivatives license.