The primitive Roman house came from the Etruscans and goes back to the simple farm life of early times.

By Dr. Harold Whetstone Johnston

Late Professor of Latin

Indiana University

The Domus

The house with which we are concerned is the residence (domus) of the single household, as opposed to lodging houses or apartment houses (īnsulae) intended for the accommodation of several families, and the residence, moreover, of the well-to-do citizen, as opposed on the one hand to the mansion of the millionaire and on the other to the hovels of the very poor. At the same time it must be understood that the Roman house did not show as many distinct types as does the American house of the present time. The Roman was naturally conservative, he was particularly reluctant to introduce foreign ideas, and his house in all times and of all classes preserved certain main features essentially unchanged. The proportion of these might vary with the size and shape of the lot at the builder’s disposal, the number of apartments added would depend upon the means and tastes of the owner, but the kernel, so to speak, is always the same, and this makes the general plan much less complex, the description much less confusing.

Our sources of information are unusually abundant. Vitruvius, an architect and engineer of the time of Caesar and Augustus, has left a work on building, giving in detail his own principles of construction; the works of many of the Roman writers contain either set descriptions of parts of houses or at least numerous hints and allusions that are collectively very helpful; and finally the ground plans of many houses have been uncovered in Rome and elsewhere, and in Pompeii we have even the walls of some houses left standing. There are still, however, despite the fullness and authority of our sources, many things in regard to the arrangement and construction of the house that are uncertain and disputed.

The Development of the House

The primitive Roman house came from the Etruscans. It goes back to the simple farm life of early times, when all members of the household, father, mother, children, and dependents, lived in one large room together. In this room the meals were cooked, the table spread, all indoor work performed, the sacrifices offered to the Lares, and at night a space cleared in which to spread the hard beds or pallets. The primitive house had no chimney, the smoke escaping through a hole in the middle of the roof. Rain could enter where the smoke escaped, and from this fact the hole was called the impluvium; just beneath it in later times a basin (compluvium) was hollowed out in the floor to catch the water for domestic purposes. There were no windows, all natural light coming through the impluvium or, in pleasant weather, through the open door. There was but one door, and the space opposite it seems to have been reserved as much as possible for the father and mother. Here was the hearth, where the mother prepared the meals, and near it stood the implements she used in spinning and weaving; here was the strong box (ārca), in which the master kept his valuables, and here their couch was spread.

The outward appearance of such a house is shown in the Etruscan cinerary urns found in various places in Italy. The ground plan is a simple rectangle without partitions. This may be regarded as historically and architecturally the kernel of the Roman house; it is found in all of which we have any knowledge. Its very name (ātrium), denoting originally the whole house, was also preserved, as is shown in the names of certain very ancient buildings in Rome used for religious purposes, the ātrium Vestae, the ātrium Lībertātis, etc., but afterwards applied to the characteristic single room. The name was once supposed to mean “the black (āter) room,” but many scholars recognize in it the original Etruscan word for house.

The first change in the primitive house came in the form of a shed or “lean-to” on the side of the ātrium opposite the door. It was probably intended at first for merely temporary purposes, being built of wooden boards (tabulae), and having an outside door and no connection with the ātrium. It could not have been long, however, until the wall between was broken through, and this once done and its convenience demonstrated, the partition wall was entirely removed, and the second form of the Roman house resulted. This improvement also persisted, and the tablīnum is found in all the houses from the humblest to the costliest of which we have any knowledge.

The next change was made by widening the ātrium, but in order that the roof might be more easily supported walls were erected along the lines of the old ātrium for about two-thirds of its depth. These may have been originally mere pillars, as nowadays in our cellars, not continuous walls. At any rate, the ātrium at the end next the tablīnum was given the full width between the outside walls, and the additional spaces, one on each side, were called ālae. The appearance of such a house as seen from the entrance door must have been much like that of an Anglican or Roman Catholic church. The open space between the supporting walls corresponded to the nave, the two ālae to the transepts, while the bay-like tablīnum resembled the chancel. The space between the outside walls and those supporting the roof was cut off into rooms of various sizes, used for various purposes. So far as we know they received light only from the ātrium, for no windows are assigned to them by Roman writers, and none are found in the ruins, but it is hardly probable that in the country no holes were made for light and air, however considerations of privacy and security may have influenced builders in the towns. From this ancient house we find preserved in its successors all opposite the entrance door: the ātrium with its ālae and tablīnum, the impluvium and compluvium. These are the characteristic features of the Roman house, and must be so regarded in the description which follows of later developments under foreign influence.

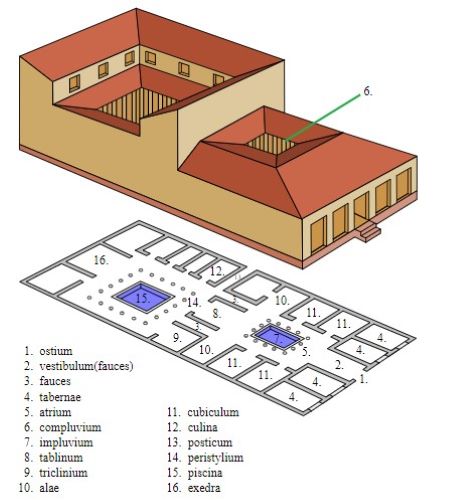

The Greeks seem to have furnished the idea next adopted by the Romans, a court at the rear of the ātrium, open to the sky, surrounded by rooms, and set with flowers, trees, and shrubs. The open space had columns around it, and often a fountain in the middle. This court was called the peristylum or peristylium. According to Vitruvius its breadth should have exceeded its depth by one-third, but we do not find these or any other proportions strictly observed in the houses that are known to us. Access to the peristylium from the ātrium could be had through the tablīnum, though this might be cut off from it by folding doors, and by a narrow passage1 by its side. The latter would be naturally used by servants and by others who did not wish to pass through the master’s room. Both passage and tablīnum might be closed on the side of the ātrium by portières. The arrangement of the various rooms around the court seems to have varied with the notions of the builder, and no one plan for them can be laid down. According to the means of the owner there were bedrooms, dining-rooms, libraries, drawing-rooms, kitchen, scullery, closets, private baths, together with the scanty accommodations necessary even for a large number of slaves. But no matter whether these rooms were many or few they all faced the court, receiving from it light and air, as did the rooms along the sides of the ātrium. There was often a garden behind the court.

The next change took place in the city and town house only, because it was due to conditions of town life that did not obtain in the country. In ancient as well as in modern times business was likely to spread from the center of the town into residence districts, and it often became desirable for the owner of a dwelling-house to adapt it to the new conditions. This was easily done in the case of the Roman house on account of the arrangement of the rooms. Attention has already been called to the fact that the rooms all opened to the interior of the house, that no windows were placed in the outer walls, and that the only door was in front. If the house faced a business street, it is evident that the owner could, without interfering with the privacy of his house or decreasing its light, build rooms in front of the ātrium for commercial purposes. He reserved, of course, a passageway to his own door, narrower or wider according to the circumstances. If the house occupied a corner, such rooms might be added on the side as well as in front, and as they had no necessary connection with the interior they might be rented as living-rooms, as such rooms often are in our own cities. It is probable that rooms were first added in this way for business purposes by an owner who expected to carry on some enterprise of his own in them, but even men of good position and considerable means did not hesitate to add to their incomes by renting to others these disconnected parts of their houses. All the larger houses uncovered in Pompeii are arranged in this manner. Such a detached house was called an īnsula.

The Vestibulum

Having traced the development of the house as a whole and described briefly its permanent and characteristic parts, we may now examine these more closely and at the same time call attention to other parts introduced at a later time. It will be convenient to begin with the front of the house. The city house was built even more generally than now on the street line. In the poorer houses the door opening into the ātrium was in the front wall, and was separated from the street only by the width of the threshold. In the better sort of houses, those described in the last section, the separation of the ātrium from the street by the row of stores gave opportunity for arranging a more imposing entrance. A part at least of this space was left as an open court, with a costly pavement running from the street to the door, adorned with shrubs and flowers, with statuary even, and trophies of war, if the owner was rich and a successful general. This courtyard was called the vestibulum. The derivation of the word is disputed, but it probably comes from ve-, “apart,” “separate,” and stāre (cf. prōstibulum from prōstāre), and means “a private standing place”; other explanations are suggested in the dictionaries.

The important thing to notice is that it does not correspond at all to the part of a modern house called after it the vestibule. In this vestibulum the clients gathered, before daybreak perhaps, to wait for admission to the ātrium, and here the sportula was doled out to them. Here, too, was arranged the wedding procession, and here was marshaled the train that escorted the boy to the forum the day that he put away childish things. Even in the poorer houses the same name was given to the little space between the door and the edge of the sidewalk.

The Ostium

The entrance to the house was called the ōstium. This includes the doorway and the door itself, and the word is applied to either, though forēs and iānua are the more precise words for the door. In the poorer houses the ōstium was directly on the street, and there can be no doubt that it originally opened directly into the ātrium; in other words, the ancient ātrium was separated from the street only by its own wall. The refinement of later times led to the introduction of a hall or passageway between the vestibulum and the ātrium, and the ōstium opened into this hall and gradually gave its name to it.

The threshold (līmen) was broad, the door being placed well back, and often had the word salvē worked on it in mosaic. Over the door were words of good omen, Nihil intret malī, for example, or a charm against fire. In the great houses where an ōstiārius or iānitor was kept on duty, his place was behind the door, and sometimes he had here a small room. A dog was often kept chained in the ōstium, or in default of one a picture was painted on the wall or worked in mosaic on the floor with the warning beneath it: Cavē canem! The hallway was closed on the side of the ātrium with a curtain (vēlum). This hallway was not so long that through it persons in the ātrium could not see passers-by in the street.

The Atrium

Overview

The ātrium was the kernel of the Roman house, and to it was given the appropriate name cavum aedium. It is possible that this later name belonged strictly to the unroofed portion only, but the two words came to be used indiscriminately. The old view that the cavum aedium was a middle court between the ātrium and the peristylium is still held by a few scholars, but is not supported by the monumental evidence. The most conspicuous features of the ātrium were the impluvium and the compluvium. The water collected in the latter was carried into cisterns; over the former a curtain could be drawn when the light was too intense, as over a photographer’s skylight nowadays. We find that the two words were carelessly used for each other by Roman writers. So important was the impluvium to the ātrium, that the latter was named from the manner in which the former was constructed. Vitruvius tells us that there were four styles. The first was called the ātrium Tūscanicum. In this the roof was formed by two pairs of beams crossing each other at right angles, the inclosed space being left uncovered and thus forming the impluvium. The name as well as the simple construction shows that this was the earliest form of the ātrium, and it is evident that it could not be used for rooms of very large dimensions. The second was called the ātrium tetrastylon. The beams were supported at their intersections by pillars or columns. The third, ātrium Corinthium, differed from the second only in having more than four supporting pillars. It is probable that these two similar styles came in with the widening of the ātrium. The fourth was called the ātrium displuviātum. In this the roof sloped toward the outer walls, and the water was carried off by gutters on the outside, the compluvium collecting only so much as actually fell into it from the heavens. We are told that there was another style of ātrium, the testūdinātum, which was covered all over and had neither impluvium nor compluvium. We do not know how this was lighted; perhaps by windows in the ālae.

The Change in the Atrium

The ātrium as it was in the early days of the Republic has been described in. The simplicity and purity of the family life of that period lent a dignity to the one-room house that the vast palaces of the late Republic and Empire failed utterly to inherit. By Cicero’s time the ātrium had ceased to be the center of domestic life; it had become a state apartment used only for display. We do not know the successive steps in the process of change. Probably the rooms along the sides were first used as bedrooms, for the sake of greater privacy. The need of a detached room for the cooking must have been felt as soon as the peristylium was adopted (it may well be that the court was originally a kitchen garden), and then of a dining-room convenient to it. Then other rooms were added about this court and these were made sleeping-apartments for the sake of still greater privacy. Finally these rooms were needed for other purposes and the sleeping-rooms were moved again, this time to an upper story. When this second story was added we do not know, but it presupposes the small and costly lots of a city. Even the most unpretentious houses in Pompeii have in them the remains of staircases.

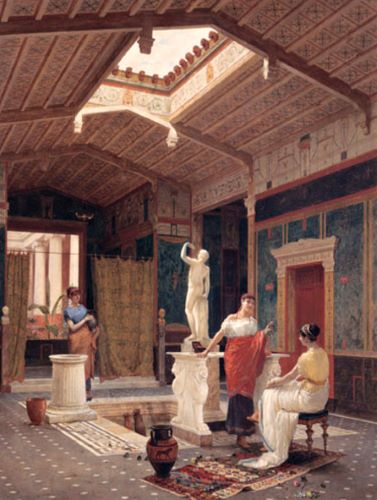

The ātrium was now fitted up with all the splendor and magnificence that the owner’s means would permit. The opening in the roof was enlarged to admit more light, and the supporting pillars were made of marble or costly woods. Between these pillars and along the walls statues and other works of art were placed. The compluvium became a marble basin, with a fountain in the center, and was often richly carved or adorned with figures in relief. The floors were mosaic, the walls painted in brilliant colors or paneled with marbles of many hues, and the ceilings were covered with ivory and gold. In such a hall the host greeted his guests, the patron received his clients, the husband welcomed his wife, and here his body lay in state when the pride of life was over.

Still some memorials of the older day were left in even the most imposing ātrium. The altar to the Lares and Penates remained near the place where the hearth had been, though the regular sacrifices were made in a special chapel in the peristylium. In even the grandest houses the implements for spinning were kept in the place where the matron had once sat among her maidservants, as Livy tells us in the story of Lucretia. The cabinets retained the masks of simpler and may be stronger men, and the marriage couch stood opposite the ōstium (hence its other name, lectus adversus), where it had been placed on the wedding night, though no one slept in the ātrium. In the country much of the old-time use of the ātrium survived even Augustus, and the poor, of course, had never changed their style of living. What use was made of the small rooms along the sides of the ātrium, after they had ceased to be bedchambers, we do not know; they served perhaps as conversation rooms, private parlors, and drawing-rooms.

The Alae

The manner in which the ālae, or wings, were formed has been explained; they were simply the rectangular recesses left on the right and left of the ātrium, when the smaller rooms on the sides were walled off. It must be remembered that they were entirely open to the ātrium, and formed a part of it, perhaps originally furnishing additional light from windows in their outer walls.

In them were kept the imāginēs, as the wax busts of those ancestors who had held curule offices were called, arranged in cabinets in such a way that, by the help of cords running from one to another and of inscriptions under each of them, their relation to each other could be made clear and their great deeds kept in mind. Even when Roman writers or those of modern times speak of the imāginēs as in the ātrium, it is the ālae that are intended.

The Tablinium

The probable origin of the tablīnum, has been explained above, and its name has been derived from the material (tabulae, “planks”) of the “lean-to,” perhaps a summer kitchen, from which it developed. Others think that the room received its name from the fact that in it the master kept his account books (tabulae) as well as all his business and private papers. He kept here also the money chest or strong box (ārca), which in the olden time had been chained to the floor of the ātrium, and made the room in fact his office or study. By its position it commanded the whole house, as the rooms could be entered only from the ātrium or peristylium, and the tablīnum was right between them.

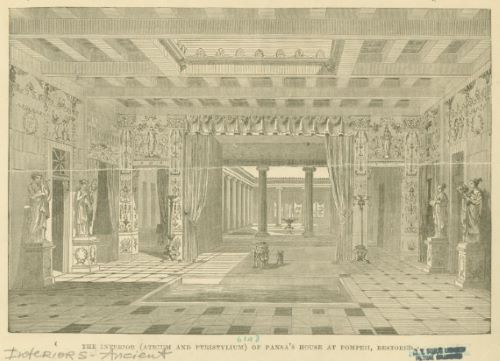

The master could secure entire privacy by closing the folding doors which cut off the private court, or by pulling the curtains across the opening into the great hall. On the other hand, if the tablīnum was left open, the guest entering the ōstium must have had a charming vista, commanding at a glance all the public and semi-public parts of the house. Even when the tablīnum was closed, there was free passage from the front of the house to the rear through the short corridor by the side of the tablīnum. It should be noticed that there was only one such passage, though the older authorities assert that there were two.

The Peristyle

The peristylium or peristylum was adopted, as we have seen, from the Greeks, but despite the way in which the Roman clung to the customs of his fathers it was not long in becoming the more important of the two main sections of the house. We must think of a spacious court open to the sky, but surrounded by a continuous row of buildings, or rather rooms, for the buildings soon became one, all facing it and having doors and latticed windows opening upon it. All these buildings had covered porches on the side next the court, and these porches forming an unbroken colonnade on the four sides were strictly the peristyle, though the name came to be used of the whole section of the house, including court, colonnade, and surrounding rooms.

The court was much more open to the sun than the ātrium, and all sorts of rare and beautiful plants and flowers bloomed and flourished in it, protected by the walls from cold winds. Fountains and statuary adorned the middle part; the colonnade furnished cool or sunny promenades, no matter what the time of day or the season of the year. Loving the open air and the charms of nature as the Romans did, it is no wonder that they soon made the peristyle the center of their domestic life in all the houses of the better class, and reserved the ātrium for the more formal functions which their political and public position demanded. It must be remembered that there was often a garden behind the peristyle, and there was also very commonly a direct connection with the street.

Private Rooms

The rooms surrounding the court varied so much with the means and tastes of the owners of the houses that we can hardly do more than give a list of those most frequently mentioned in literature. It is important to remember that in the town house all these rooms received their light by day from the court, while in the country there may well have been windows and doors in the exterior wall. First in importance comes the kitchen (culīna), placed on the side of the court opposite the tablīnum. It was supplied with an open fireplace for roasting and boiling, and with a stove not unlike the charcoal affairs still used in Europe. Near it was the bakery, if the mansion required one, supplied with an oven. Near it, too, was the bathhouse (lātrīna) with the necessary closet, in order that all might use the same connection with the sewer. If the house had a stable, it was also put near the kitchen, as nowadays in Latin countries.

The dining-room (trīclīnium) may be mentioned next. It was not necessarily in immediate juxtaposition to the kitchen, because the army of slaves made its position of little importance so far as convenience was concerned. It was customary to have several trīclīnia for use at different seasons of the year, in order that the room might be warmed by the sun in winter, and in summer escape its rays. Vitruvius thought that its length should be twice its breadth, but the ruins show no fixed proportions. The Romans were so fond of the air and the sky that the court must have often served as a dining-room, and Horace has left us a charming picture of the master dining under an arbor attended by a single slave. Such an outdoor dining-room is found in the so-called House of Sallust at Pompeii.

The sleeping-rooms (cubicula) were not considered so important by the Romans as by us, for the reason, probably, that they were used merely to sleep in and not for living-rooms as well. They were very small and the furniture was scant in even the best houses. Some of these seem to have had anterooms in connection with the cubicula, which were probably occupied by attendants, and in even the ordinary houses there was often a recess for the bed. Some of the bedrooms seem to have been used merely for the midday siesta, and these were naturally situated in the coolest part of the court; they were called cubicula diurna. The others were called by way of distinction cubicula nocturna or dormitōria, and were placed so far as possible on the west side of the court in order that they might receive the morning sun. It should be remembered that in the best houses the bedrooms were preferably in the second story of the peristyle.

A library (bibliothēca) had a place in the house of every Roman of education. Collections of books were large as well as numerous, and were made then as now by persons even who cared nothing about their contents. The books or rolls, which will be described later, were kept in cases or cabinets around the walls, and in one library discovered in Herculaneum an additional rectangular case occupied the middle of the room. It was customary to decorate the room with statues of Minerva and the Muses, and also with the busts and portraits of distinguished men. Vitruvius recommends an eastern aspect for the bibliothēca, probably to guard against dampness.

Besides these rooms, which must have been found in all good houses, there were others of less importance, some of which were so rare that we scarcely know their uses. The sacrārium was a private chapel in which the images of the gods were kept, acts of worship performed, and sacrifices offered. The Lar or tutelary divinity of the house seems, however, to have retained his ancient place in the ātrium. The oecī were halls or saloons, corresponding perhaps to our parlors and drawing-rooms, used occasionally, it may be, for banquet halls. The exedrae were rooms supplied with permanent seats which seem to have been used for lectures and similar entertainments. The sōlārium was a place to bask in the sun, sometimes a terrace, often the flat roof of the house, which was then covered with earth and laid out like a garden and made beautiful with flowers and shrubs. Besides these there were, of course, sculleries, pantries, and storerooms. The slaves had to have their quarters (cellae servōrum), in which they were packed as closely as possible. Cellars under the houses seem to have been rare, though some have been found at Pompeii.

The House of Pansa

Finally we may describe a house that actually existed, taking as an illustration one that must have belonged to a wealthy and influential man, the so-called House of Pansa at Pompeii. The house occupied an entire square, facing a little east of south. Most of the rooms on the front and sides were rented out for shops or stores; in the rear was a garden. The rooms that did not belong to the house proper are shaded in the plan here given.

The vestibulum, marked 1 in the plan, is the open space between two of the shops. Behind it is the ōstium (1′), with a figure of a dog in mosaic, opening into the ātrium (2, 2) with three rooms on each side, the ālae (2′, 2′) being in the regular place, the compluvium (3) in the middle, the tablīnum (4) opposite the ōstium, and the passage on the eastern side (5). The ātrium is of the Tūscanicum style, and is paved with concrete; the tablīnum and the passage have mosaic floors. From these, steps lead down into the court, which is lower than the ātrium, measures 65 by 50 feet, and is surrounded by a colonnade with sixteen pillars. There are two rooms on the side next the ātrium, one of these (6) has been called the bibliothēca, because a manuscript was found in it, but its purpose is uncertain; the other (6′) was possibly a dining-room. The court has two projections (7′, 7′) much like the ālae, which have been called exedrae; it will be noticed that one of these has the convenience of an exit to the street. The rooms on the west and the small room on the east can not be definitely named. The large room on the east (T) is the main dining-room, the remains of the dining couches being marked on the plan. The kitchen is at the northwest corner (13), with the stable (14) next to it; off the kitchen is a paved yard (15) with a gateway into the street by which a cart could enter.

East of the kitchen and yard is a narrow passage connecting the peristyle with the garden. East of this are two rooms, the larger of which (9) is one of the most imposing rooms of the house, 33 by 24 feet in size, with a large window guarded by a low balustrade, and opening into the garden. This was probably an oecus. In the center of the court is a basin about two feet deep, the rim of which was once decorated with figures of water plants and fish. Along the whole north end of the house ran a long veranda (16, 16), overlooking the garden (11, 11) in which was a sort of summer house (12). The house had an upper story, but the stairs leading to it are in the rented rooms, suggesting that the upper floor was not occupied by Pansa’s family.

Of the rooms facing the street it will be noticed that one, lightly shaded in the plan, is connected with the ātrium; it was probably used for some business conducted by Pansa himself, possibly with a slave or a freedman in immediate charge of it. Of the others the suites on the east side (A, B) seem to have been rented out as living apartments. The others were shops and stores. The four connected rooms on the west, near the front, seem to have been a large bakery; the room marked C was the salesroom, with a large room opening off of it containing three stone mills, troughs for kneading the dough, a water tap with sink, and a recessed oven. The uses of the others are uncertain. The section plan represents the appearance of the house if all were cut away on one side of a line drawn from front to rear through the middle of the house. It is, of course, largely conjectural, but gives a clear idea of the general way in which the division walls and roof must have been arranged.

The Walls

Overview

The materials of which the wall (pariēs) was composed varied with the time, the place, and the cost of transportation. Stone and unburned bricks (laterēs crūdī) were the earliest materials used in Italy, as almost everywhere else, timber being employed for merely temporary structures, as in the addition from which the tablīnum developed. For private houses in very early times and for public buildings in all times, walls of dressed stone (opus quadrātum) were laid in regular courses, precisely as in modern times. Over the wall was spread a coating of fine marble stucco for decorative purposes, which gave it a finish of dazzling white. For less pretentious houses, not for public buildings, the sun-dried bricks were largely used up to about the beginning of the first century B.C. These, too, were covered with the stucco, for protection against the weather as well as for decoration, but even the hard stucco has not preserved walls of this perishable material to our times. In classical times a new material had come into use, better than either brick or stone, cheaper, more durable, more easily worked and transported, which was employed almost exclusively for private houses, and very generally for public buildings. Walls constructed in the new way (opus caementīcium) are variously called “rubble-work” or “concrete” in our books of reference, but neither term is quite descriptive; the opus caementīcium was not laid in courses, as is our rubble-work, while on the other hand larger stones were used in it than in the concrete of which walls for buildings are now constructed.

Paries Caementicius

The materials varied with the place. At Rome lime and volcanic ashes (lapis Puteolānus) were used with pieces of stone as large or larger than the fist. Brickbats sometimes took the place of stone, and sand that of the volcanic ashes; potsherds crushed fine were better than the sand. The harder the stones the better the concrete; the very best was made with pieces of lava, the material with which the roads were generally paved. The method of forming the concrete walls was the same as that of modern times, familiar to us all in the construction of sidewalks. It will be easily understood from the illustration. Upright posts, about 5 by 6 inches thick, and from 10 to 15 feet in height, were fixed about 3 feet apart along the line of both faces of the intended wall. On the outside of these were nailed horizontally boards, 10 or 12 inches wide, overlapping each other. Into the intermediate space the semi-fluid concrete was poured, receiving the imprint of posts and boards. When the concrete had hardened, the frame-work was removed and placed on top of it and the work continued until the wall had reached the required height. Walls made in this way varied in thickness from a seven-inch partition wall in an ordinary house to the eighteen-foot walls of the Pantheon of Agrippa. They were far more durable than stone walls, which might be removed stone by stone with little more labor than was required to put them together; the concrete wall was a single slab of stone throughout its whole extent, and large parts of it might be cut away without diminishing the strength of the rest in the slightest degree.

Wall Facings

Impervious to the weather though these walls were, they were usually faced with stone or kiln-burned brick (laterēs coctī). The stone employed was usually the soft tufa, not nearly so well adapted to stand the weather as the concrete itself. The earliest fashion was to take bits of stone having one smooth face but of no regular size or shape and arrange them with the smooth faces against the frame-work as fast as the concrete was poured in. Such a wall was called opus incertum. In later times the tufa was used in small blocks having the smooth face square and of a uniform size. A wall so faced looked as if covered with a net and was therefore called opus rēticulātum. A section at a corner is shown at C. In either case the exterior face of the wall was usually covered with a fine limestone or marble stucco, which gave a hard finish, smooth and white. The burned bricks were triangular in shape. It must be noticed that there were no walls made of laterēs coctī alone, even the thin partition walls having a core of concrete.

Floors and Ceilings

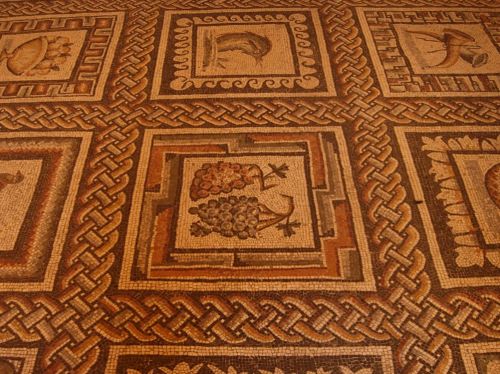

In the poorer houses the floor (sōlum) of the first story was made by smoothing the ground between the walls, covering it thickly with small pieces of stone, bricks, tile, and potsherds, and pounding all down solidly and smoothly with a heavy rammer (fistūca). Such a floor was called pavīmentum, and the name came gradually to be used of floors of all kinds. In houses of a better sort the floor was made of stone slabs fitted smoothly together.

The more pretentious houses had concrete floors, made as has been described. Floors of upper stories were sometimes made of wood, but concrete was used here, too, poured over a temporary flooring of wood. Such a floor was very heavy, and required strong walls to support it; examples are preserved of the thickness of eighteen inches and a span of twenty feet. A floor of this kind made a perfect ceiling for the room below, requiring only a finish of stucco. Other ceilings were made much as they are now, laths being nailed on the stringers or rafters and covered with mortar and stucco.

Roofs

The construction of the roofs (tēcta) differed very little from the modern method. They varied as much as ours do in shape, some being flat, others sloping in two directions, others in four. In the most ancient times the covering was a thatch of straw, as in the so-called hut of Romulus (casa Rōmulī) on the Palatine Hill preserved even under the Empire as a relic of the past. Shingles followed the straw, only to give place in turn to tiles. These were at first flat, like our shingles, but were later made with a flange on each side in such a way that the lower part of one would slip into the upper part of the one below it on the roof. The tiles (tēgulae) were laid side by side and the flanges covered by other tiles, called imbricēs inverted over them. Gutters also of tile ran along the eaves to conduct the water into cisterns, if it was needed for domestic purposes..

Doors and Windows

The Roman doorway, like our own, had four parts: the threshold (līmen), the two jambs (postēs), and the lintel (līmen superum). The lintel was always of a single piece of stone and peculiarly massive. The doors were exactly like those of modern times, except in the matter of hinges, for while the Romans had hinges like ours they did not use them on their doors. The door-hinge was really a cylinder of hard wood, a little longer than the door and of a diameter a little greater than the thickness of the door, terminating above and below in pivots. These pivots turned in sockets made to receive them in the threshold and lintel. To this cylinder the door was mortised, their combined weight coming upon the lower pivot. The cut makes this clear, and reminds one of an old-fashioned homemade gate. The comedies are full of references to the creaking of these doors.

The outer door of the house was properly called iānua, an inner door ōstium, but the two words came to be used indiscriminately, and the latter was even applied to the whole entrance. Double doors were called forēs, and the back door, usually opening into a garden, was called the postīcum. The doors opened inwards and those in the outer wall were supplied with bolts (pessulī) and bars (serae). Locks and keys by which the doors could be fastened from without were not unknown, but were very heavy and clumsy. Finally it should be noticed that in the interiors of private houses doors were not nearly so common as now, the Romans preferring portières (vēla, aulaea).

In the principal rooms of the house the windows opened on the court, as has been seen, and it may be set down as a rule that in rooms situated on the first floor and used for domestic purposes there were no windows opening on the street. In the upper floors there must have been windows on the street in such apartments as had no outlook on the court, as in those for example above the rented rooms in the House of Pansa. Country houses may also have had outside windows in the first story. All the windows (fenestrae) were small, hardly larger than three feet by two. Some were provided with shutters, which were made to slide backward and forward in a frame-work on the outside of the wall. These shutters were sometimes in two parts moving in opposite directions, and when closed were said to be iūnctae. Other windows were latticed, and others still were covered with a fine network to keep out mice and other objectionable animals. Glass was known to the Romans of the Empire but was too expensive for general use. Talc and other translucent materials were also employed in window frames as a protection against cold, but only in very rare instances.

Heating and Water Supply

Even in the mild climate of Italy the houses must often have been too cold for comfort. On merely chilly days the occupants probably contented themselves with moving into rooms warmed by the direct rays of the sun, or with wearing wraps or heavier clothing. In the more severe weather of actual winter they used charcoal stoves or braziers of the sort that is still used in the countries of southern Europe. They were merely metal boxes in which hot coals could be put, with legs to keep the floors from injury and handles by which they could be carried from room to room. They were called foculī. The wealthy had furnaces resembling ours under their houses, the heat being carried to the rooms by tile pipes; in some instances the partitions and floors seem to have been made of hollow tiles, through which the hot air circulated, warming the rooms without being admitted to them. These furnaces had chimneys, but furnaces were seldom used.

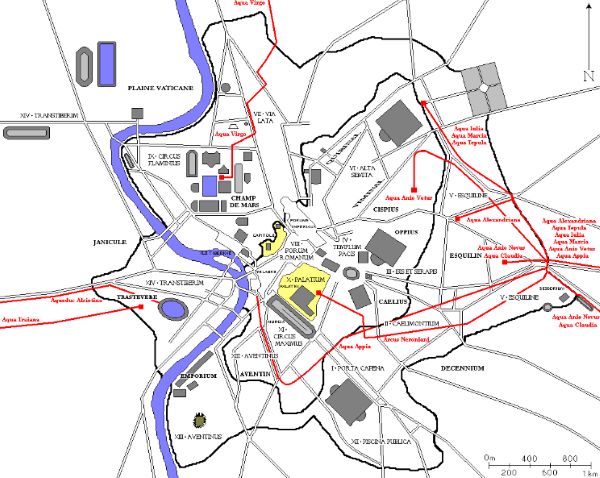

All the important towns of Italy had abundant supplies of water piped from hills and brought sometimes from a considerable distance. The Romans’ aqueducts were among their most stupendous and most successful works of engineering. Mains were laid down the middle of the streets and from these the water was piped into the houses. There was often a tank in the upper part of the house, from which the water was distributed as it was needed. It was not usually carried into many of the rooms, but there was always a jet or fountain in the court, in the bathhouse, the garden, and the closet. The bathhouse had a separate heating apparatus of its own, which kept the room or rooms at the desired temperature and furnished hot water as required.

Decoration

The outside of the house was left severely plain, the walls being merely covered with stucco, as we have seen. The interior was decorated to suit the tastes and means of the owner, not even the poorer houses lacking charming effects in this direction. At first the stucco-finished walls were merely marked off into rectangular panels (abacī), which were painted deep, rich colors, reds and yellows predominating. Then in the middle of these panels simple center-pieces were painted and the whole surrounded with the most brilliant arabesques. Then came elaborate pictures, figures, interiors, landscapes, etc., of large size and most skillfully executed, all painted directly upon the wall, as in some of our public buildings to-day. A little later the walls began to be covered with panels of thin slabs of marble with a baseboard and cornice. Beautiful effects were produced by combining marbles of different tints, and the Romans ransacked the world for striking colors. Later still came raised figures of stucco work, enriched with gold and colors, and mosaic work, chiefly of minute pieces of colored glass which had a jewel-like effect.

The doors and doorways gave opportunities for treatment equally artistic. The doors were richly paneled and carved, or were plated with bronze, or made of solid bronze. The threshold was often of mosaic. The postēs were sheathed with marble elaborately carved, as in the example from Pompeii. The floors were covered with marble tiles arranged in geometrical figures with contrasting colors, much as they are now in public buildings, or with mosaic pictures only less beautiful than those upon the walls. The most famous of these, “Darius at the Battle of Issus,” is shown in black and white in all our reference books. It measures sixteen feet by eight, but despite its size has no less than one hundred and fifty separate pieces to each square inch. The ceilings were often barrel-vaulted and painted brilliant colors, or were divided into panels (lacūs, lacūnae), deeply sunk, by heavy intersecting beams of wood or marble, and then decorated in the most elaborate manner with raised stucco work, or gold or ivory, or with bronze plates heavily gilded.

Furniture

Overview

Our knowledge of Roman furniture is largely indirect, because only such articles have come down to us as were made of stone or metal. Fortunately the secondary sources are abundant and good. Many articles are incidentally described in works of literature, many are shown in the wall paintings mentioned above, and some have been restored from casts taken in the hardened ashes of Pompeii and Herculaneum. In general we may say that the Romans had very few articles of furniture in their houses, and that they cared less for comfort, not to say luxurious ease, than they did for costly materials, fine workmanship, and artistic forms. The mansions on the Palatine were enriched with all the spoils of Greece and Asia, but it may be doubted whether there was a comfortable bed within the walls of Rome.

Principal Articles

Many of the most common and useful articles of modern furniture were entirely unknown to the Romans. No mirrors hung on their walls, they had no desks or writing tables, no dressers or chiffoniers, no glass-doored cabinets for the display of bric-a-brac, tableware, or books, no mantels, no hat-racks even. The principal articles found in even the best houses were couches or beds, chairs, tables, and lamps. If to these we add chests or cabinets, an occasional brazier, and still rarer water-clock, we shall have everything that can be called furniture except tableware and kitchen utensils. Still it must not be thought that their rooms presented a desolate or dreary appearance. When one considers the decorations, the stately pomp of the ātrium, and the rare beauty of the peristyle, it is evident that a very few articles of real artistic excellence were more in keeping with them than would have been the litter and jumble that we now think necessary in our rooms.

Couches

The couch (lectus, lectulus) was found everywhere in the Roman house, a sofa by day, a bed by night. In its simplest form it consisted of a frame of wood with straps across the top on which was laid a mattress. At one end there was an arm, as in the case of our sofas; sometimes there was an arm at each end, and a back besides. It was always provided with pillows and rugs or coverlets. The mattress was originally stuffed with straw, but this gave place to wool and even feathers. In some of the bedrooms of Pompeii the frame seems to have been lacking, the mattress being laid on a support built up from the floor. The couches used for beds seem to have been larger than those used as sofas, and they were so high that stools or even steps were necessary accompaniments. As a sofa the lectus was used in the library for reading and writing, the student supporting himself on the left arm and holding the book or writing with the right hand. In the dining-room it had a permanent place, as will be described later. Its honorary position in the great hall has been already mentioned. It will be seen that the lectus could be made highly ornamental. The legs and arms were carved or made of costly woods, or inlaid or plated with tortoise-shell or the precious metals. We even read of frames of solid silver. The coverings were often made of the finest fabrics, dyed the most brilliant colors and worked with figures of gold.

Chairs

The primitive form of seat (sedīle) among the Romans as elsewhere was the stool or bench with four perpendicular legs and no back. The remarkable thing is that it did not give place to something better as soon as means permitted. The stool (sella) was the ordinary seat for one person, used by men and women resting or working, and by children and slaves at their meals as well. The bench (subsellium) differed from the stool only in accommodating more than one person. It was used by senators in the cūria, by the jurors in the courts, and by boys in the school, as well as in private houses. A special form of the sella was the famous curule chair (sella curūlis), having curved legs of ivory. The curule chair folded up like our camp-stools for convenience of carriage and had straps across the top to support the cushion which formed the seat.

The first improvement upon the sella was the solium, a stiff, straight, high-backed chair with solid arms, looking as if cut from a single block of wood, and so high that a footstool was as necessary with it as with a bed. Poets represented gods and kings as seated in such a chair, and it was kept in the ātrium for the use of the patron when he received his clients. Lastly, we find the cathedra, a chair without arms, but with a curved back sometimes fixed at an easy angle (cathedra supīna), the only approximation to a comfortable seat that the Romans knew. It was at first used by women only, being regarded as too luxurious for men, but finally came into general use. Its employment by teachers in the schools of rhetoric gave rise to the expression ex cathedrā, applied to authoritative utterances of every kind, and its use by bishops explains our word cathedral. Neither the solium nor the cathedra was upholstered, but with them both were used cushions and coverings as with the lectī, and they afforded like opportunities for skillful workmanship and lavish decoration.

Tables

The table (mēnsa) was the most important article of furniture in the Roman house whether we consider its manifold uses, or the prices often paid for certain kinds. They varied in form and construction as much as our own, many of which are copied directly from Roman models. All sorts of materials were used for their supports and tops, stone, wood, solid or veneered, the precious metals, probably in thin plates only. The most costly, so far as we know, were the round tables made from cross-sections of the citrus-tree, found in Africa. The wood was beautifully marked and single pieces could be had from three to four feet in diameter. For one of these Cicero paid $20,000, Asinius Pollio $44,000, King Juba $52,000, and the family of the Cethegi possessed one valued at $60,000. Special names were given to tables of certain forms.

The monopodium was a table or stand with but one support, used especially to hold a lamp or toilet articles. The abacus was a table with a rectangular top having a raised rim and used for plate and dishes, in the place of the modern sideboard. The delphica (sc. mēnsa) had three legs. Tables were frequently made with adjustable legs, so that the height might be altered. On the other hand the permanent tables in the trīclīnia were often built up from the floor of solid masonry or concrete, having tops of polished stone or mosaic. The table gave a better opportunity than even the couch or chair for artistic workmanship, especially in the matter of carving and inlaying the legs and top.

Lamps

The Roman lamp (lucerna) was essentially simple enough, merely a vessel that would hold oil or melted grease with a few threads twisted loosely together for a wick and drawn out through a hole in the cover or top. The light thus furnished must have been very uncertain and dim. There was no glass to keep the flame steady, much less was there a chimney or central draft. As works of art, however, they were exceedingly beautiful, those of the cheapest material being often of graceful form and proportions, while to those of costly material the skill of the artist in many cases must have given a value far above that of the rare stones or precious metals of which they were made.

Some of these lamps were intended to be carried in the hand, as shown by the handles, others to be suspended from the ceiling by chains. Others still were kept on tables expressly made for them, as the monopodia commonly used in the bedrooms, or the tripods. For lighting the public rooms there were, besides these, tall stands, like those of our piano lamps, examples of which may be seen in the last cut. On some of these, several lamps perhaps were placed at a time. The name of these stands (candēlābra) shows that they were originally intended to hold wax or tallow candles (candēlae), and the fact that these candles were supplanted in the houses of the rich by the smoking and ill-smelling lamp is good proof that the Romans were not skilled in the art of making them. Finally it may be noticed that a supply of torches (facēs) of dry, inflammable wood, often soaked in oil or smeared with pitch, was kept near the outer door for use upon the streets.

Chests and Cabinets

Every house was supplied with chests (ārcae) of various sizes for the purpose of storing clothes and other articles not always in use, and for the safe keeping of papers, money, and jewelry. The material was usually wood, often bound with iron and ornamented with hinges and locks of bronze. The smaller ārcae, used for jewel cases, were often made of silver or even gold. Of most importance, perhaps, was the strong box kept in the tablīnum, in which the pater familiās stored his ready money. It was made as strong as possible so that it could not easily be opened by force, and was so large and heavy that it could not be carried away entire. As an additional precaution it was sometimes chained to the floor. This, too, was often richly carved and mounted, as is seen in the illustration from Pompeii.

The cabinets (armāria) were designed for similar purposes and made of similar materials. They were often divided into compartments and were always supplied with hinges and locks. Two of the most important uses of these cabinets have been mentioned already: in the library for the preserving of books against mice and men, and in the ālae for the keeping of the imāginēs, or death-masks of wax. It must be noticed that they lacked the convenient glass doors of the cabinets or cases that we use for books and similar things, but they were as well adapted to decorative purposes as the other articles of furniture that have been mentioned.

Other Articles

The heating stove, or brazier, has been already described. It was at best a poor substitute for the poorest modern stove. The place of our clock was taken in the court or garden by the sun-dial (sōlārium), such as is often seen nowadays in our parks, which measured the hours of the day by the shadow of a stick or pin. It was introduced into Rome from Greece in 268 B.C. About a century later the water-clock (clepsydra) was also borrowed from the Greeks, a more useful invention because it marked the hours of the night as well as of the day and could be used in the house. It consisted essentially of a vessel filled at a regular time with water, which was allowed to escape from it at a fixed rate, the changing level marking the hours on a scale. As the length of the Roman hours varied with the season of the year and the flow of the water with the temperature, the apparatus was far from accurate. Shakspere’s striking of the clock in “Julius Caesar” (II, i, 192) is an anachronism. Of the other articles sometimes reckoned as furniture, the tableware and kitchen utensils, some account will be given elsewhere.

The Street

It is evident from what has been said that a residence street in a Roman town must have been severely plain and monotonous in its appearance. The houses were all of practically the same style, they were finished alike in stucco, the windows were few and in the upper stories only, there were no lawns or gardens, there was nothing in short to lend variety or to please the eye, except perhaps the decorations of the vestibula, or the occasional extension of one story over another (maeniānum), or a public fountain.

The street itself was paved, as will be explained hereafter, and was supplied with a footway on either side raised from twelve to eighteen inches above its surface. The inconvenience of such a height to persons crossing from one footway to the other was relieved by stepping-stones (pondera) of the same height firmly fixed at suitable distances from each other across the street. These stepping-stones were placed at convenient points on each street, not merely at the intersections of two or more streets. They were usually oval in shape, had flat tops, and measured about three feet by eighteen inches, the longer axis being parallel with the walk. The spaces between them were often cut into deep ruts by the wheels of vehicles, the distance between the ruts showing that the wheels were about three feet apart.

Chapter 6 from The Private Life of the Romans, by Harold Whetstone Johnston (1903), published by Project Gutenberg to the public domain.