People drank for many different reasons and these reasons ranged across social class, gender, and region.

By Dr. Thora Hands

Professor of the History of Alcohol and Drug Use

City of Glasgow College

Introduction

This offers different and sometimes contrasting perspectives on the reasons why alcohol was consumed and on the drinking cultures that emerged from the Victorian period. Alcohol played a key role in the everyday lives of men and women across Britain. It was not only consumed in pubs, restaurants, theatres, refreshment rooms and many other public places but also in the privacy of people’s homes or in private members clubs.

People drank for many different reasons and these reasons ranged across social class, gender and region. In the nineteenth century, alcohol still held a vital place in medical practice and was prescribed for a range of physiological and psychological illnesses. Even when its use in therapeutics began to fall out of fashion, late Victorian consumers relied upon alcohol as a tonic that could be used for the purposes of self-medication.

Doctor’s Orders: A Prescription to Drink

This part considers the use of alcohol by the medical profession. In the last quarter of the nineteenth century, doctors began to debate the efficacy of alcohol as a therapeutic drug and the moral implications of prescribing alcohol to patients. Alcohol was still used to treat a wide range of psychological and physiological illnesses but debates existed over the issue of therapeutic nihilism – whether alcohol did more harm than good and while some doctors held faith in its therapeutic qualities, others disagreed. The chapter draws upon an analysis of hospital records which show that alcohol use gradually declined in the period leading up to the First World War when the financial and moral cost of alcohol began to impact upon its popularity as a prescribed medicine.

During the last few years there has been a decided boom in certain sophisticated wines – ‘dietetic’ or ‘tonic’ or ‘restorative’ beverages. Undoubtedly the public imagination has been captured by the ingenious methods pursued in pushing these productions … [Of] those most puffed in the newspapers and advertised in the press and on public boardings, it may be safely affirmed that they have no appreciable therapeutic influence other than that possessed by any of the ordinary wines on the market.1

Throughout the Victorian and Edwardian periods, people consumed alcohol for health reasons. This was driven in part by the use of alcohol in medical practice and also by commercial factors, which played a significant role in promoting ideas about the health benefits of consuming certain alcoholic drinks. The quote above is from an article on the sale of tonic wines in the British Journal of Inebriety in 1910. The article offered a scathing attack on what the writer referred to as the ‘ingenious’ and ‘aggressive’ marketing of tonic wines which were accused of holding little therapeutic value and could potentially lead to alcoholism.2 The writer, a doctor and magistrate, noted the popularity of tonic wines which were one of many types of proprietary remedies widely available in the late Victorian period. This chapter explores the issue of drinking for health in the late Victorian and early Edwardian periods by examining the controversy that surrounded the medicinal use of alcohol. Debates about the efficacy of alcohol as a therapeutic agent circulated in medical journals towards the end of the century. An analysis of hospital records shows that although its usage diminished in the period leading up to the First World War, doctors still relied upon it to treat a range of physiological and psychological illnesses. Alcohol had been used as a staple drug in medical practice since the seventeenth century.3 Its usage within medicine continued throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and the general public therefore had good reason to believe in its medicinal power. Prescriptions for alcohol became increasingly popular in the nineteenth century when more heroic methods of treatment such as cupping and bloodletting fell out of use. However, doctors came under attack from temperance campaigners both inside and outside of the medical profession because a prescription to drink had moral and medical implications and by the end of the century, its usage within hospitals and asylums had declined.

By the late nineteenth century, debates existed on the therapeutic value of alcohol and despite its enduring status as a staple medicine, some doctors avoided prescribing it altogether. At the core of these debates was the issue of therapeutic nihilism—whether prescribing alcohol actually did more harm than good. The effects of alcohol on health were poorly understood and medical opinions were not only based on scientific evidence but sometimes on moral grounds. In a presidential address given to the British Society for the Study of Inebriety in July 1907, Dr Harry Campbell scrutinised the contents of a recently published medical manifesto on the influence of alcohol on health. He focused on a section of the manifesto which claimed that in the opinion of the medical signatories moderate drinking was beneficial to health

It is [according to the manifesto] the “moderate” use of alcoholic beverages that is held to be “usually beneficial.” Now, what are we to understand by moderate? The signatories make no attempt to define the word. They should have told us what they regard as the limits of moderation – how much, i.e., a person may drink daily without forfeiting the claim to be considered a moderate drinker. Is moderate indulgence the equivalent of one, two, three, or four glasses of whisky per diem? Are we to take as the standard of moderation, the smallest or the largest quantity of alcohol daily consumed by any one of the signatories, or the mean of their respective total daily consumption? We need explicit information on this head. The term “moderate” is in truth a highly elastic one, possessing very different meanings for different individuals. I recently asked a casual acquaintance what he understood by moderate and he gave as answer “half a bottle of whisky a day.” And I told him that I was going to suggest two glasses, or their equivalent to which he replied that a man who limited himself to so small a quantity was to all intents and purposes a teetotaller!4

Campbell went further to suggest that the failure to quantify moderate drinking was matched by a failure to stipulate which types of alcohol should be considered ‘moderate drinks’ that were beneficial to health. He believed that the quality and type of alcohol were key factors in determining its effects on human health. Campbell concluded that

The mouthpiece of the British medical profession, would have you to understand that nine-tenths of you will be benefited in health by the moderate use of alcoholic beverages, but we leave it to you to decide what a moderate quantity is, and you may choose any kind of alcoholic drink your fancy prompts.5

Doctors could not agree on ‘healthy’ amounts of alcohol consumption or if alcohol was beneficial in therapeutics. In a presidential address to The British Medical Association in 1905, Dr James Barr gave a speech on the use of alcohol as a therapeutic agent in which he argued that less alcohol was prescribed because of ‘fashion’ rather than from any scientific reasoning on its usefulness as a medicine

There is no other drug in the pharmacopeia that has such an accommodating action to circumstances. It would seem as if in any particular case we could never predicate as to whether alcohol is going to do good or harm. Surely some indications could be laid down for its use so that we should know beforehand what effect it is going to produce.6

Barr called for more scientific research on the uses and effects of alcohol as a therapeutic drug because he believed that it remained useful in medicine and more importantly, despite the controversy over its use, many doctors still prescribed it anyway. To illustrate this point Barr set out the principal therapeutic uses of alcohol in treating a range of illnesses: In the treatment of pneumonia he personally recommended the use of a ‘light draught beer’ as a sedative and in typhoid fever a ‘pint of good bitter’ was given in small doses over twenty-four hours. Cases of vomiting were treated with small doses of champagne and brandy was administered in cases of collapse or shock. For palliative care, he noted that diluted brandy was often given freely in the last days of life and for invalids it was common to prescribe ‘a good port’ during periods of convalescence.7 In the treatment of nervous diseases, alcohol was used as a sedative and an analgesic. Cases of neuralgia were treated with a ‘glass of good stout’ and for cases of angina, hot whisky or brandy were recommended.8 Barr described alcohol as a versatile drug that was available in a variety of forms that could be used to treat a range of illnesses. He believed that this made it a valuable medicine that should not be swept aside by fashion or moral concerns. Yet some doctors were critical of what they believed to be the morally questionable practice of prescribing alcohol. In 1885, Dr Norman Kerr, the prominent temperance campaigner and founder of the British Society for the Study of Inebriety, urged caution when prescribing any alcohol

We can never forget that intoxicating drinks cannot be ordered without some risk of a taste for them being acquired, and the remedy itself proving worse than the original disease. This risk was exemplified in the case of a favourite dog of two maiden ladies of my acquaintance. This animal was seized with an attack of acute pneumonia. The veterinary surgeon gave the dog brandy; and the dog recovered, whether because of or in spite of the stimulant, I cannot tell. Ever since, if he hears anyone speak of brandy, he is up in a moment on his hind legs, begging for the seductive physic. Though I believe the cases of what may be called ‘medical drunkenness’ are not nearly as numerous as is popularly asserted, I have known instances where the medical prescription of strong drinks has been the beginning of a career of excess.9

Kerr’s opinion was based on his belief that for some individuals (and dogs), alcohol was a dangerously addictive substance. He, therefore, believed that the continued use of alcohol in therapeutics could lead to an increase in cases of ‘medical drunkenness’ which could in turn damage the reputation of the profession. In a speech given two decades later to the Lancashire and Cheshire branch of the British Medical Profession, Dr Charles Macfie echoed Kerr’s views regarding the use of alcohol in medicine.10 Macfie believed that doctors had a duty to promote and support temperance reform, particularly when increasing scientific evidence and medical opinions suggested that alcohol was not conducive to good health. Like Kerr, he also believed that by continuing to prescribe alcohol, the medical profession risked damaging its reputation. Macfie gave the example of recent accusations by some temperance groups that increasing amounts of inebriety were due to taking alcohol ‘under doctor’s orders’

This insinuation is a glaring economy of the truth and before such insinuations are published to the world, one would expect any fair minded society or individual to first probe the truth about ‘doctor’s orders.’ There are two sides to a ladder. No drunkard ever takes the blame for his or her degraded condition as the profession so well knows. According to them, their own family circle and nearest friends are their direst enemies; and how often has a chimerical ‘doctor’s order’ been given as an excuse! I could understand our being urgently requested to avoid prescribing alcohol in any form, on account of the moderate use of it becoming a habit and ultimately developing into a craving. The medical profession is as anxious that alcohol should not be abused and that human beings should not suffer in mind and body from its effects, as any teetotaller can possibly be.11

Although he had reservations about the validity of the claims made by the temperance groups, Macfie remained concerned that prescribing alcohol could bring the profession into disrepute because a prescription to drink could be risky—not only in terms of ethics but also in the damage it might do to professional reputation. Yet others were concerned about the implications of reducing or stopping the use of alcohol in medicine. In an article in the British Medical Journal in 1890, one doctor (who remained anonymous) highlighted the differences in alcohol use between workhouses and general hospitals

The general hospitals throughout the country have very materially reduced their expenditure on alcohol in all its forms, but the general hospitals have not abandoned its use in toto … The class of cases in the union infirmaries [where no alcohol was prescribed] are exactly identical with those in the general hospitals. The workhouse medical officer has to treat pneumonia and other acute diseases and grave surgical operations are performed in many union hospitals. At the Leeds General Infirmary alcohol is used. Must we conclude that the staff of Leeds General Infirmary are wrong in continuing this agent?12

Evidently, this doctor was concerned that the welfare of patients was put at risk by a distinction based on moral rather than medical grounds. Alcohol still held value within therapeutics and in surgical procedures and therefore to deny it to patients within workhouse hospitals must have seemed ethically questionable. However, temperance debates aside, by the early twentieth century there was growing scientific evidence for restricting the use of alcohol in medicine. Macfie referred to several studies that challenged the prevailing view that alcohol provided stimulation in cases of disease and debility.13 These studies showed that alcohol also had an irritant or depressive action on nerves and body tissues. Macfie also pointed out that there were alternatives to alcoholic stimulation in therapeutics

In turning to our Pharmacopeia and our Extra Pharmacopeia for substitutes for alcohol, we are at once impressed with the fact that most drugs have more or less stimulant properties, either local or general, for example, phosphorus, arsenic and iron, chloroform and the ethers, and the various alkaloids – all stimulant in medicinal doses.14

By the early twentieth century, there were pharmaceutical alternatives to alcohol that challenged its efficacy as a drug. Yet some doctors still believed that alcohol had an important place within therapeutics. In a speech given in 1909 to the Border Counties Branch of the British Medical Profession, Dr James MacDonald set out a convincing argument in favour of the continued, judicious use of alcohol in the treatment of illness and disease.15 He argued that advances in medical knowledge were not sufficient to dismiss the role of alcohol as a valuable medicine

There are of course habits and fashions in therapeutics as in everything else. Fashions in the past have sometimes been regulated by the prevailing theory of the origin of disease. In the days, for example, when diseases were set down to inflammation, bloodletting was all the vogue, and the use of alcohol was looked on as a perilous enormity. Then came the period when our bodily ills were ascribed to lowered vitality, and the stimulants were administered to therapeutic excess. At the present day, the bacterial origin of disease does not materially affect the employment of alcohol, which is generally given with judgment and discretion.16

In other words, the advent of germ theory did not radically change the role of alcohol in therapeutics. MacDonald believed that increased knowledge of the aetiology of disease meant that alcohol was prescribed more accurately and only when absolutely necessary. He argued that this change was not enough for the medical advocates of temperance reform who warned the profession to stop prescribing alcohol or face ‘the high road to therapeutic nihilism.’17 Which meant that by continuing to prescribe alcohol the medical profession risked doing more harm than good. MacDonald questioned the professional integrity of medical men who put their ‘extreme’ personal beliefs about temperance above their duty to patients. He cited an article published in The Lancet in 1908 written by a group of ‘well-known medical experts’ who expressed the view that alcohol was a ‘rapid and trustworthy restorative’ that in some cases could be a ‘life saving drug.’18 MacDonald believed that the majority of doctors shared these views

The manifesto discharges a kindly service as a protest against the uncompromising opposition of a body of extremists to the rational use of alcohol. It does more – it applies a spur to the indifference displayed by many medical men with regard to an eminently practical question. It is true that on minor points a divergence of opinion exists, but on fundamental principles there is common agreement.19

This ‘common agreement’ was evident in hospital records which show that up until the First World War alcohol was still used in large urban voluntary hospitals and asylums. Although its use may have courted controversy among medical men and temperance organisations, the continued use of alcohol indicates that it was still widely regarded as a reliable therapeutic drug. There were very few prescription drugs that offered the same degree of versatility to treat fevers, disease, debility and provide a degree of comfort for patients during the course of illness. Alcohol was the rational drug of choice because it was relatively cheap, widely available and came in a variety of different forms that suited the needs of a wide range of patients.

Alcohol Use in Hospitals and Asylums

The value of alcohol was evident in hospital records which show that various types of alcoholic drinks were used in the treatment of patients suffering from a range of psychological and physiological conditions. The records of four Glasgow hospitals show that between 1870 and 1914, alcohol was still used in the treatment of patients. During this period, Glasgow was one of the largest industrial cities in Britain and rapid population growth meant increasing problems associated with ill health and disease.20 The city therefore makes a good case study for the therapeutic use of alcohol in the treatment of illness. The records of Glasgow Royal Infirmary; Gartnavel Royal Lunatic Asylum; The Western Infirmary and Hawkhead Asylum show increasing numbers of admissions in the late Victorian and Edwardian periods. Hospital expenditure on alcohol sometimes correlated with the number of admissions either increasing or decreasing according to the numbers of patients admitted and treated. Yet as the graphs show, between 1875 and 1914 there was a general trend towards growing numbers of admissions and decreasing expenditure on alcohol (Graph 9.1).

The graph shows that until 1895 alcohol use fluctuated. In 1891 there was a sharp increase in expenditure on alcohol but it is unclear from the records why more was spent in that year. It could be that particular types of admissions required treatment with alcohol. According to the 1891 records of the Registrar General for Scotland the highest numbers of deaths in Glasgow in that year were from bronchitis and pneumonia, which were predominantly secondary infections. The highest numbers of deaths from contagious diseases in 1891 related to measles, whooping cough and phthisis (tuberculosis).22 It may be that these types of illnesses required therapeutic treatment with alcoholic stimulants. The graph shows that by 1914, despite a large amount of civilian and military admissions, the use of alcohol had declined. The wartime restrictions on alcohol may account in part for this decrease (Graph 9.2).

The graph shows fluctuating levels of expenditure on alcohol until 1879 when there was a marked trend towards higher admissions and less spent on alcohol. There is no evidence in the annual reports of decisions taken to restrict the medicinal use of alcohol but the increased numbers of admissions in 1885 coupled with the decreased expenditure on alcohol suggest a shift in hospital policy (Graph 9.3).

The data from the Western Infirmary shows a negative correlation between increasing numbers of admissions from 1895 onwards and decreasing expenditure on alcohol. By 1905, alcohol expenditure had fallen significantly despite a sharp increase in admissions in the same year. This is a similar pattern to that found in Glasgow Royal Infirmary and may be indicative of the financial constraints posed by larger numbers of admissions. This contrasts with the data shown below from a smaller institution, Hawkhead asylum where expenditure on alcohol remained fairly consistent until 1912 when it began to decline (Graph 9.4).

The data from the Glasgow hospitals suggests that overall expenditure on alcohol varied across different types of institutions and changed over time. It also shows a general trend towards restricting expenditure on alcohol. It is however difficult to ascertain exactly how the alcohol purchased was used in the treatment of patients and why this changed over time. In each of the institutions, the ward casebooks and patient notes lacked detailed information on treatment regimes and more specifically, on any alcohol prescribed. There was a case in Gartnavel Royal Asylum of a male patient admitted in 1888 suffering from ‘low mood’ exacerbated by bronchitis, who was prescribed 4 grams of whisky daily plus an expectorant mixture.26 In the annual report for 1871, the medical superintendent of Gartnavel discussed the use of alcohol and stated that

There are a number of weak, helpless bed-rid patients, especially in the East House, suffering from various diseases of long standing, many of whom were organically affected on admission … While all the patients require to be well nourished and supported and are so, these patients, in consequence of their greater want of vitality, often require food to be expressly prepared for them and with stimulants to be administered both night and day with a large amount of kind and considerate treatment.27

It would therefore appear that alcohol played an important role in the treatment of chronic diseases and palliative care. In another Scottish asylum, The Chrichton Royal, alcohol was sometimes used in the treatment of private patients—even those with existing alcohol problems. One patient admitted in 1886 suffering from eccentric and delusional behaviour was allowed generous amounts of alcohol. His case notes stated that

Mr H has resided at Kirkmichael House all winter and has had shooting all the season. He has been fairly contented as long as he had unlimited meal and drink. His appetite was enormous and at a meal he has been known to eat a leg of mutton with the usual accessories…and finish off with half a dozen eggs…he has been allowed three glasses of whisky daily and as much beer as he chose to drink. He usually took the whisky undiluted.28

This case highlights the differences in treatment with alcohol among private and pauper patients. Even if viewed as a necessary therapeutic agent, alcohol was an additional expense in the course of treatment and perhaps one that hospitals with larger numbers of pauper patients could ill afford. In addition to the asylums, alcohol was also used in the treatment of infectious diseases in Belvedere (fever) Hospital in Glasgow. In the 1866 annual report the medical superintendent of Belvedere noted that during the typhus epidemic of 1861 and 1862, the hospital admitted 1837 patients and of these, 1289 were typhus cases.29 The alcohol consumed during this period was: 62,754 ounces of wine, 8440 ounces of whisky and 2611 ounces of brandy.30 The Medical Superintendent, Dr Russell believed that it was important to weigh up the therapeutic benefits of ‘alcoholic stimulation’ with the economic considerations. He stated that during the typhus epidemic, Belvedere Hospital and Glasgow Royal Infirmary had admitted similar numbers of typhus cases and that both hospitals had used alcohol in the treatment of patients. Yet Belvedere had successfully treated patients with a more judicious use of alcoholic stimulants than the Royal Infirmary. In fact, Dr Russell claimed that there were fewer deaths from typhus in Belvedere than in the Royal Infirmary and that the average length of stay was considerably less in the former.31

The use of alcohol in treating fevers and other illnesses was reported in medical journals. Aside from the financial implications of alcohol use, some doctors believed that it only held therapeutic value in certain cases and in particular stages of illness and disease. In an article in the British Medical Journal in 1880, Dr H. McNaughton a physician in The Fever Hospital Cork, provided evidence to support his claim that alcohol should be prescribed carefully in fever cases.32 He kept records of his patients from January 1873 to June 1879, a period in which he treated 889 fever cases mainly typhus, typhoid and simple fever. On average 30% of patients were treated with alcohol during this period.33 Most fever cases were treated using brandy, claret and wine. He provided a patient case study of a girl he described as being one of the worst cases of typhoid fever he had ever treated. In the early stages of her illness he prescribed no alcohol but instead treated her using milk, beef extract, foul-broth, digitalis, ipecacuanha (an expectorant sometimes used to treat dysentery), Dover’s Powders, quinine and opium. In the later stages of illness, he prescribed a mixture of brandy and milk every four hours and one ounce of claret every two hours. The girl recovered completely.34

The type of alcohol used in the treatment of illness and disease varied. This was reflected in the Glasgow hospital data. The most popular types of alcohol purchased during the 1870–1914 period were wines and champagne, brandy, whisky, porter and beer. Most hospitals held accounts with local wine and spirit merchants and the Royal Infirmary bought alcohol from two Glasgow firms: Samuel Dow and Thomas Anderson. The quantities and types of drinks purchased changed from year to year, sometimes reflecting the numbers of patients treated but at other times it seemed that certain drinks became more popular or fell out of use. Graph 9.5 shows the changing types and quantities of alcohol purchased by Glasgow Royal Infirmary over a 30-year period.

Certain types of drinks like porter and port wine remained popular over the 30-year period. Sherry fell out of use but champagne and claret were in more demand towards the end of the century. Coleman’s Wincarnis Tonic Wine was purchased for the first time in 1891 with a sizeable order totalling £61 3s 12d, which in today’s money equates to an annual spend of around £3665 on tonic wine.36 The data from the Glasgow hospitals suggests that between 1870 and 1914, the types of alcohol purchased by hospitals changed, and that although there was an overall trend towards spending less on alcohol, its usage continued.

As many doctors still prescribed alcohol, it fell to the medical profession to investigate its role in the treatment of illness and disease. Between 1880 and 1914 there were articles in The British Medical Journal and The Lancet that investigated the use of alcohol in medical practice. Some of these articles provided chemical analyses of various alcoholic drinks because it was considered important that doctors were informed of the best types and quality of wines and spirits to prescribe to patients. Following the reduction in duties on imported wines from France, two articles appeared in The Lancet in June and July 1880. The articles were titled ‘The Lancet Commission on the Medical Use of Wines’ and each instalment dealt with different varieties of French wines. The first article in June 1880 stated

We cannot believe that any wines whatever are necessary for a healthy adult in good physical strength, taking a fair amount of daily exercise and with no excessive mental strain. Most light wines taken sparingly with meals do no harm to a person under the same conditions and are quite as consistent as the consumption of tea, coffee etc. which generally take their place. Indeed, strong tea, strong coffee and (we would add strong tobacco) have much to answer for in the production of indigestion and nervous palpitation … To the invalid, the wines are frequently of great value and in some of the acute fevers the most powerful alcoholic beverages have sometimes to be prescribed … [However] the patient’s daily question “what shall I drink?” requires more consideration than is usually devoted to it before the medical advisor gives the stereotyped reply “Oh you can take a little claret”.37

Both articles aimed to educate doctors on the composition and therapeutic value of various types of French wines. This was achieved by providing chemical analyses of the four basic constituents of wines, namely alcohol, sugar, acid and tannin. The articles claimed that differing levels of each of these constituents not only altered the taste and quality of the wine but also its therapeutic value.38 In the case of claret it was noted that there were huge differences in the quality and chemical composition of this particular type of wine but it was still believed to have medicinal applications

In cases of anaemia, ordinary debility from overwork, feeble digestion etc., a sound red claret is almost as good a prescription as most of the tonic drugs in the Pharmacopeia and is always an advantageous adjunct to this class of remedies. Of course, it must only be taken with the meals and in no case should more than half a bottle be permitted with the meal. In this quantity, the amount of alcohol is very small.39

Although the articles aimed to give a scientific analysis of the therapeutic value of wine, each instalment also provided information on sourcing the best vintages and brands. For example, an analysis of white Bordeaux wines used ‘an excellent Sauterne 1870 from The Cafe Royale’ to highlight the therapeutic qualities of that particular type of wine.40 Another article in The Lancet in 1894 looked at the medical value of ‘tonic’ champagnes such as Laurent-Perrier Grand Vin Brut Champagne Sans Sucre and Coca Tonic Champagne Sans Sucre which were recommended for use in treating diabetic patients. Chemical analyses of both drinks concluded that they were palatable and of a similar quality to other ‘high class’ champagnes.41 Although there was no medical consensus on the therapeutic value of alcohol as a generic drug there did seem to be some agreement that if alcohol were to be used, it should be of the best quality and type. This is hardly surprising, given that most doctors were middle-class men and many of their fee-paying patients were also middle and upper class. The range of illnesses that were financially treatable with a ‘sound claret’, coca champagne or a good quality brandy were therefore likely to be middle or upper-class illnesses such as fatigue, neurasthenia, exhaustion from overwork and digestive complaints. In this sense, doctors were only prescribing the types of alcoholic drinks that their patients would normally drink anyway, so in effect it was a prescription to drink well.

The financial aspect of prescribing alcohol was perhaps more of a concern for public hospitals and asylums that had to justify expenditure on the poorer working classes. The Glasgow hospital and asylum records show a general decrease in spending on alcohol during a period when it’s continued use within medicine courted controversy. Although some doctors wanted to distance the profession from the moral taint of intemperance, many were prepared to carry on prescribing alcohol because they had faith in its therapeutic value. One important point to consider is that alcohol was still being bought and used within hospitals and this suggests a lack of viable alternatives at that time. In other words, doctors simply had no other choice but to prescribe alcohol and perhaps the real pressure was to do so judiciously. This could certainly account for the decrease in the use of alcohol in the decades leading up to the First World War.

Drinking for Health: Proprietary Tonic Wines

This part examines the practice of drinking alcohol for health reasons. This was driven in part by the use of alcohol in medical practice but also by commercial factors, which played a significant role in promoting ideas about the health giving benefits of consuming certain alcoholic drinks. The chapter explores the ideas and controversies that surrounded the medicinal use of alcohol through a case study of Wincarnis Tonic Wine, which was one of the leading brands of tonic wine in the late nineteenth century. Political and medical debates existed about the therapeutic value of proprietary tonic wines which were sold and purchased as a means of self-medication for a range of psychological and physiological ailments.

To the medically uneducated public [meat and malt wines] undoubtedly seem a most promising combination: extract of meat for food, extract of malt to aid digestion, port wine to make blood – surely the very thing to strengthen all who are weak and to hasten the restoration of convalescents. Unfortunately, what the advertisements say – that this stuff is largely prescribed by medical men – is not wholly true.42

In an article in The British Medical Journal in 1898, Dr F. C. Coley argued that doctors should warn patients and the general population to be wary when buying meat and malt wines. The problem with tonic wines was that they made bold therapeutic claims about the health-giving properties of alcohol based on flimsy medical evidence. Although the therapeutic use of alcohol was generally supported and propagated by doctors who wrote prescriptions for alcohol, it was important that its therapeutic use remains within the boundaries of medical control and not be thrown open to ‘the medically uneducated public.’ In other words, alcohol still had a place in medicine but the general public could not be trusted to use it wisely or responsibly. Yet despite the reservations of the medical profession, tonic wines were a commercial success and the idea of drinking for health was popular among alcohol consumers.

Foley’s argument highlights one of the main concerns about the marketing of tonic wines expressed by the 1914 Commission on Patent Medicines, which investigated the supposed endorsement of these products by the medical profession. The committee was acting upon ethical and moral concerns about the promotion of alcohol consumption for medical reasons. Dr Mary Sturge was called as an expert witness with professional experience on the effects of medicated wines. She was asked her opinion on why people buy tonic wine

I think one of the answers is that the advertisements are most extremely attractive and alluring. I have brought a group of advertisements here … One advertisement states that ‘Wincarnis is a natural nerve and brain food’ … I do not consider that anything which contains twenty percent of alcohol, which is a nerve depressant and a nerve irritant, has any claim to be called a brain food. Then there is the advertisement: ‘Nurse? One moment please. Wincarnis gives a strength that is lasting because in each wineglassful of Wincarnis there is a standardized amount of nutriment.’ That is calculated to make people think that it is really a nutritious mixture and when it comes to the analysis, we find that the little amount of meat extract is nothing approaching the amount of an ordinary cup of beef tea. My point is the misleading influence of the advertisements.43

Dr Sturge believed that the general public was duped into buying and consuming tonic wine because they were either unaware of the alcohol content or believed that alcohol acted as a medium for the delivery of medicinal agents in the drink. There was no legal compulsion for manufacturers to disclose the alcohol content or ingredients in tonic wine on product labelling or advertising and these products fell into the category of ‘secret remedies’, which the committee defined as proprietary medicines where the labelling contained very little information on the contents and the product advertising made false or misleading claims. It was known that companies like Coleman and Hall made huge profits from the sale of their tonic wines and the issue that the committee had to consider was whether the public would continue to buy these products if they displayed accurate information on the alcohol content and added ingredients. The manufacturers claimed that by disclosing this information, their products would face increased competition, which would in turn harm their businesses. The key question for the committee was whether product labelling was in the best interests of consumers and this rested on establishing the reasons why people bought tonic wines in the first place. Dr Sturge shared the opinion that the general public viewed these products as medicines rather than alcoholic drinks. She also believed that some people simply did not care to know the alcohol content or believed that the alcohol content was minimal. She gave the example of her senior nurse

I asked my out-patient superintending nurse what she thought was in Wincarnis and she said “I think it is a nice mixture with perhaps a little alcohol in it.” The word win did not mean wine to her, although she is an intelligent woman.44

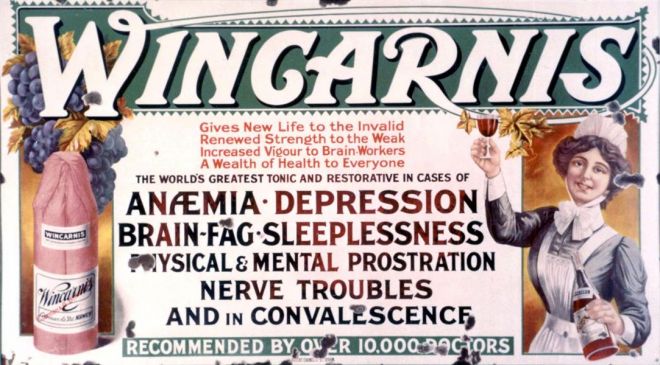

The example of a senior nurse’s ignorance over the product labelling was perhaps intended to point the finger of blame towards the manufacturer’s misleading advertising (see Figs. 10.1, 10.2, 10.3, and 10.4).

The committee heard evidence from Mr William Rudderham, who was the general manager of Coleman & Co. Ltd., the manufacturer of Wincarnis. The company spent £50,000 annually on advertising the product and Rudderham admitted that the success of Wincarnis was largely due to the ambitious marketing campaign.45 Coleman’s advertised the product in many of the London newspapers such as The Times, The Star, The Illustrated London News and The Penny Illustrated Paper . The adverts shown are typical examples of those that appeared in national and regional newspapers in England and Scotland. These adverts were themed around the medical uses of Wincarnis as an alleged treatment or cure for a range of physiological and psychological illnesses such as fatigue, brain exhaustion, worry, nervousness, influenza and pneumonia. All of the adverts shown were reliant upon two main strategies to sell the product: one was the use of testimonials from customers and from doctors and the other was the offer of a free sample for the price of a stamp—also known as the coupon system.

Figure 10.1 is typical of adverts that played on concepts of class and gender roles. In the advert, a man is pictured sitting working at his desk while a woman (presumably his wife) brings him a glass of Wincarnis ‘by doctor’s orders.’ The caption claimed that: ‘a man who spends his energies recklessly will quickly overdraw his account at the Bank of Health. A man as he manages himself may die old at thirty or young at eighty; brain fag is the foster parent of disease.’ In other words, overwork meant an early demise for professional middle-class men and an early widowhood for their wives, unless it was kept in check by a glass or two of Wincarnis. The medical claims of Wincarnis are more obvious in Fig. 10.2, which shows a nurse holding a tray containing an overly large bottle of the product beneath the caption ‘The famous winter wine tonic.’ This advert ran in March, perhaps to target people suffering from winter respiratory infections. It claimed that Wincarnis could not only treat winter illnesses but could also be used to prevent them. The medicinal qualities of Wincarnis were further supported by claims that it was used in nursing homes, hospitals and by the Royal Army Medical Corps. This apparent of the product by the medical profession was one of the advertising claims that the committee took issue with. On some Wincarnis labelling it was stated that the product was ‘recommended by 10,000 medical men.’ When asked by the committee if this claim was based on fact, Rudderham replied that the company had letters from doctors requesting free samples and that these counted as endorsements of the product. In fact, the ‘recommendations’ of 10,000 medical men were the return coupons for free samples.

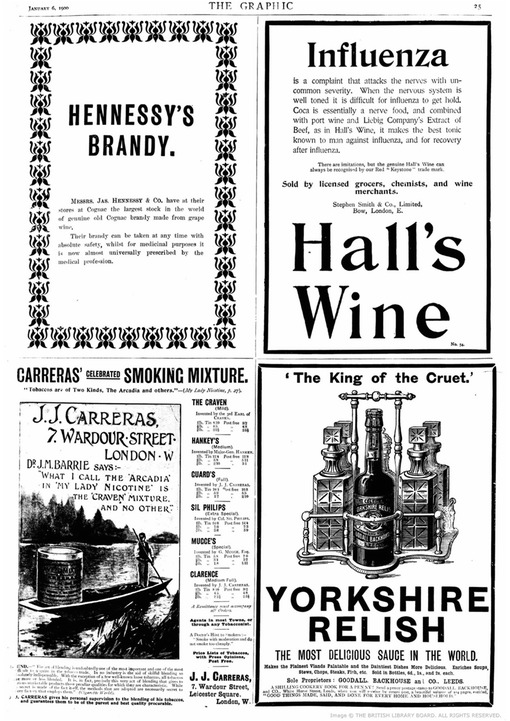

Coleman was not the only company using this marketing technique. The committee also heard evidence from Mr Henry James Hall, managing director of Stephen Smith & Co., producers of Hall’s Tonic Wine, which differed from Wincarnis in that it contained quantities of coca extract, which was essentially cocaine. Both products were marketed in a similar way, as medicinal wines recommended by the medical profession. Hall stated that: ‘Apart from our advertising, the sale of Hall’s wine is largely influenced by the recommendations of doctors.’46 To support his statement, he produced letters from doctors and gave these to the committee as proof that doctors who had tried his product had voluntarily given the recommendations. On examining the letters, the committee found that some simply thanked the company for the receipt of free samples. Hall was asked if any of the letters came from doctors who had associations with the company because it was known that a large number of doctors held shares in Stephen Smith & Co. and two doctors were members of the board of directors. Hall dodged this question by reiterating that he had letters from doctors who were not associated with the company. Medical endorsement was the main line of defence used by both Hall and Rudderham to counter the committee’s accusations that they were in fact knowingly selling alcohol under the guise of a medicine and worse still, that their products were recommended for use by women and children. Some of the Wincarnis advertising did specifically target women, mainly for obstetric and gynaecological complaints but also for psychological problems. For example, an advert for ‘Coleman’s Delicious Wincarnis’ that appeared in the Penny Illustrated Paper in May 1908 stated: ‘For the housewife: When mother’s patience is taxed to the uttermost by domestic worries and she is almost ready to faint, Wincarnis is comforting and sustaining.’47 When asked if he considered it to be morally questionable and physically harmful to encourage women and children to drink alcohol, Hall stated that

This (his product) is recommended as a tonic and a restorative and when it has effected its purpose, these people do not continue to take it. They are not going to give three shillings and sixpence for a bottle of wine which does not do them any good. I say that in the case of these people who require the wine, who have been recommended to take the wine by medical men or have been directed to take it by our advertisements, after it does what we state, they leave off taking it.48

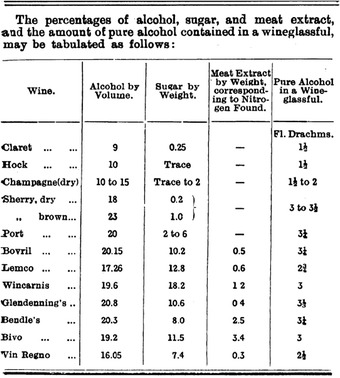

When questioning both Hall and Rudderham, the committee referred to analyses of their products, which appeared in articles in The British Medical Journal in March and May 1909. The articles published the results of chemical tests carried out on some of the most popular brands of proprietary tonic wines, as shown in Fig. 10.5.

Although not pitched as exposés, the articles revealed that most brands of tonic wines contained high levels of alcohol and very little else. Rudderham was asked if he believed that people, and particularly women, bought Wincarnis in the belief that it was a medicine that did not contain any alcohol. Rudderham replied that it clearly stated on the bottle that it was a wine and that ‘three small wineglassfuls should be taken daily’ and therefore he found it hard to believe that there could be any confusion over the alcohol content of the product. However, Dr Sturge provided statements from doctors and temperance groups which suggested that people were buying and consuming tonic wine in the belief that it was non-alcoholic. In one case, a women’s temperance group known as The White Ribboners, complained that ‘many’ of their members had drank tonic wine but were entirely oblivious to the alcohol content. In another case, a doctor from Leeds reported that one of his female patients began drinking Wincarnis when she was ‘run down’ after her second pregnancy. The woman continued to drink it in increasingly large amounts before moving on to drink spirits instead. At which point she reportedly became ‘hopelessly insane.’48 Dr Sturge argued that women drank medicated wine on a daily basis because they believed that the products provided strength and nourishment during and after pregnancy and childbirth. She essentially implied that women would only drink for health reasons and not for the purposes of pleasure or intoxication. Another witness, Mr John Charles Umney, managing director of the firm that produced Marza Tonic Wine, made the point that the word ‘wine’ in tonic wine indicated an alcohol content. Moreover, anyone who drank tonic wine would know that it produced a physiological effect. In other words, they would feel slightly drunk.

The issue of intoxication was central to the committee’s deliberations on the labelling and advertising of tonic wines. Despite evidence to the contrary, it must have seemed unlikely that men and women who purchased bottles of Hall’s Tonic Wine or Wincarnis were completely unaware of any alcohol content. It may have seemed more likely that people did not know of the relatively high alcohol content or the very small amounts of ‘medicinal’ ingredients contained in the drinks. Depending on the reasons for drinking, intoxication was either the intended primary effect or simply a side effect of the drink. In any case, the commercial success of tonic wine was unlikely to have been based on the belief that it was a non-alcoholic medicine. Most people would have known it was wine and because it was sold as a medicinal drink, people could consume alcohol for health reasons. In the case of women of all social classes, tonic wine provided a socially acceptable way to purchase and consume alcohol in private, for their own purposes and beyond the male gaze. For middle-class men and women, tonic wine perhaps offered an intoxicating relief from the pressures of work or domesticity. In this sense, Wincarnis and other tonic wines created a viable means of intoxication by promoting the idea of drinking for health reasons.

Tonic wine also provided a means of self-medication for people who could not afford to see a doctor or would not see a doctor for trivial ailments. In the last half of the nineteenth century, people were bombarded with adverts for various brands of tonic wines. An Internet search of the British Newspaper Archive for ‘tonic wine’ generated the highest number of results in the period from 1850 to 1899.49 Most of these results were for advertisements that appeared in national and regional newspapers across Britain. Alcohol producers, wine and spirit merchants, licensed grocers and chemists were most likely to place adverts. For example, there was an advert in The Burnley Express in February 1892 for ‘Wilkinson’s Orange Quinine Tonic Wine’, which was described as ‘pure genuine wine of the Seville orange’ and was recommended for use in treating influenza, debility and loss of appetite. The wine was sold in all Co-operative stores in Burnley ‘at very low prices’.50 Quinine was a popular additive to tonic wine, not only because of its supposed health-giving qualities but also because of its flavour, which was often described as pleasantly bitter or refreshing. Another advertisement for quinine wine appeared in The Pall Mall Gazette in July 1899. The advert was for ‘Quinquina Dubonnet’ which was described as an ‘appetizing, stimulating and strengthening tonic wine of the most delicious flavour made solely from Old Muscat wine and Mexican Quinquina.’51 Dubonnet Tonic Wine was developed by a French chemist during the French conquest of North Africa in the 1830s. It was designed to encourage the legionnaires to take quinine in a palatable form in order to combat malaria.52 Another popular ingredient in tonic wine was coca extract, which was sometimes coupled with quinine. An advert for ‘Coca and Cinchona (quinine) Wine’ appeared in The Bath Chronicle in January 1889. The wine was intended for use in treating cases of neuralgia and was available from a local chemist in Bath.53 Chemists often advertised various brands of tonic wines. One advert that appeared in The Arbroath Herald in June 1898 promoted the sale of ‘wines for invalids’ and listed various brands of meat and malt wines, invalid port and coca wine.54 Some of the most widely advertised tonic wines were Hall’s Tonic Wine and Mariani Wine. The adverts provide examples (Figs. 10.6 and 10.7).

There was profit in selling alcohol as a tonic and companies such as Hall were not the only ones to use this tactic. In the late Victorian period, W & A Gilbey, one of the leading wine and spirit merchants in Britain, stated in its 1897 company report that inserting the word ‘invalid’ onto the labelling of various ports, wines and champagnes, had greatly increased sales of these products.55 Gilbey had used this marketing strategy for a number of years and the 1885 price list included a large section on ‘special wines for the use of invalids’ which contained invalid champagnes, meat and malt tonic port, quinine sherry, coca wines and invalid port—all sold under the company Castle brand name. One advert for Castle Invalid Port contained an extract from an 1885 article in The Times which claimed

Dr Hood says: “there is no more wholesome wine than genuine port when it is well matured. Two or three glasses daily of such wine will act as a grateful stimulant to the stomach and will assist digestion. Dr. Mortimer Granville states: “stimulants are almost always, I believe, necessary in cases of gout tendency and during the intervals of these attacks. I impose no restrictions except that all alcoholic beverages shall be taken with food and that new or imperfectly fermented wines shall be avoided.56

An 1892 sales report stated that in a recent influenza epidemic, more than 200,000 bottles of invalid wines and champagnes had been sold. This gives some sense of the popularity and reliance upon alcoholic substances as medicinal tonics. Doctors still prescribed alcohol as a medicine and consumers also used it as a means of self-medication. It is hardly surprising that the drink trade capitalised on this and marketed products accordingly. As a tonic, alcohol could be drunk moderately and respectably to alleviate a myriad of psychological and physiological problems. This was an attractive idea—particularly for certain groups of consumers who could not otherwise drink without incurring social and moral disapproval. Yet the idea that alcohol was a tonic divided the opinions of the medical profession, and the claim that Wincarnis was endorsed by ‘thousands of medical men’ was based on very thin evidence. The company could, however, have legitimately claimed that the medical profession still relied upon wine in the treatment of disease and illness. The use of alcohol in medicine not only held commercial value but it also shaped public opinion on the substance and thus partly influenced consumer choices. From a consumers’ perspective—if doctors were prescribing alcohol and companies were selling it as a preventative and cure-all for virtually all forms of ill health, then it must have been very tempting to turn to alcohol for comfort and relief. The tonic wine boom is perhaps proof of that.

Neither Carnival nor Lent: Everyday Working Class Drinking

This part explores the drinking cultures of the working classes through analysis of oral history interviews conducted in the 1970s on surviving Victorians and Edwardians. These interviews reveal another side to working class drinking, where alcohol consumption revolved around family life, work and leisure. This stands in contrast to the way in which working class drinking was often portrayed as either ‘carnivalesque’ or ‘teetotal’ in political discourse. In fact, everyday working class drinking was much more humdrum and routine.

The true role of drinking in Edwardian Britain was much more humdrum. Beer was the basis of leisure. It took the place which later became filled with cigarettes and television. Children would fetch jugs from the pubs for tired parents to relax at home at the end of the day. At funerals, at weddings, at harvest, at the initiation of apprentices, at ordinary work breaks, a glass of beer would be exchanged.57

For most of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, moral and political concerns about alcohol consumption rested on the types of working-class drinking behaviour constantly on show in pubs and on the streets. Yet as the quote above suggests, there was another side to working-class drinking where alcohol formed an ordinary part of everyday life. The quote is from Paul Thompson, a sociologist who conducted an oral history study of Edwardian family life.58 By stepping into the private world of the family, Thompson’s study revealed a culture of ‘everyday’ drinking among ordinary people. Accounts of excessive drinking were widely documented in the press and in official reports, yet the more humdrum, routine and private drinking habits that existed across the social spectrum largely escaped public scrutiny.

The chapter draws upon an analysis of oral history transcripts which offer glimpses of the ways in which working-class men and women consumed alcohol and their reasons for doing so. This is not a ‘top down’ vision of working-class drinking skewed by political motives or temperance ideology. Instead, it offers first-hand accounts of drinking based upon the experiences and memories of surviving Victorians and Edwardians. Many contemporaries (and some historians) looked no further than the publicly drunken aspects of Victorian working-class drinking culture that seemed to be evident on city streets or in pubs, theatres and dance halls. Joseph Gusfield argues that this type of ‘carnival and lent’ analysis of working-class drinking can be traced to the process of industrialisation and the consequent separation between daily work and leisure.59 As alcohol consumption was less acceptable in the workplace, it became a marker of leisure time—a symbol of free time spent away from work. The drinking culture of the working classes was viewed as ‘carnivalesque’ precisely because it ran counter to the sobriety, efficiency and self-control demanded by industrial capitalism. Yet for many working-class families, free time was spent at home, where alcohol formed an integral part of the daily routine that signalled the end of the working day.

Leisure time was one of the many aspects explored in Thompson’s study of Edwardian work and family life. The research was conducted in the 1970s when it was still possible to interview surviving Victorians and Edwardians in Britain. The study comprised 444 interviews with men and women all born between 1872 and 1906.60 Thompson endeavoured to provide a representative sample of the Edwardian population based upon the 1911 census. The interviewees consisted of men and women from all social classes and occupational groups who were living in urban and rural regions of England, Scotland and Wales. The interview schedule consisted of a list of questions that included the roles and work of family members, for example cooking, dining, domestic routines and family values. The interviews were open-ended and some of the questions concerned alcohol consumption. The main questions relating to alcohol were:

Did your mother or father brew their own beer or make wine? (this question was only directed at working-class interviewees).2.

Did your mother or father go to the pub? (this question was put to all the interviewees).

The interviews lasted between one and six hours and therefore the original transcripts are lengthy (a full extract of data from the original transcripts can be found in the Appendix).61 The questions on alcohol were mostly asked in a set order but a close reading of the interview transcripts revealed that the interviewees sometimes provided additional anecdotal information about alcohol in other sections of the interviews. Both working-class and middle-class people were interviewed and asked questions that related to alcohol consumption and drinking behaviour. The middle-class interviews will be dealt with in the next chapter which considers the private drinking culture of the higher classes.

The Edwardians study is relevant because it goes beyond the ‘carnivalesque’ drinking culture of the streets to examine drinking in the context of everyday family life where alcohol formed a part of the daily routine. This offers insights into how working-class people thought about drinking and also into the ways in which alcohol was produced and consumed. There is rich qualitative data on attitudes towards alcohol consumption, which sometimes reflect the social and cultural values of different groups of working-class people. Yet the use of oral history transcripts can have potential pitfalls: These were old men and women recollecting events from their childhoods and they may have forgotten or exaggerated details. However, this was a large representative study that interviewed a wide range of people and it is possible to see patterns in the responses, which suggests some accuracy of detail. But accuracy was not the main reason for using the oral history transcripts. The study provides a unique opportunity to ‘listen’ to what Victorians and Edwardians had to say about alcohol consumption and to set their discussions and views within the social and cultural context of the time. It was not intended to use The Edwardians study to uncover any ‘truths’ about alcohol consumption but instead to gain deeper insights into different types of drinking.

Another relevant sociological study is The Pub and the People , which was a Mass Observation Study conducted in ‘Worktown’ in the 1930s.62 Worktown was in fact Bolton, an industrial town in the north of England which had a population of 180,000 people and 300 pubs. The study was conducted over four years between 1938 and 1942 and involved qualitative interviews, observation and the collection of data and statistics. Although the study offers a snapshot of drinking behaviour in the interwar years, some of the interviewees had been alive in the Victorian and Edwardian periods and therefore they brought with them some ingrained drinking habits and attitudes towards alcohol consumption. The interviewees shared their reasons for drinking particular types of alcohol and these reasons offer insights into the ways in which working-class consumers justified their drinking behaviour. The Worktown study provides a contrast to The Edwardians study because it focuses on the public drinking culture of the pub whereas The Edwardians drinking is largely situated in the home. When combined, these studies provide insights into working-class drinking within different social, spatial and temporal contexts.

For Victorian and Edwardian working-class families, patterns of drinking largely revolved around family life and home consumption of alcohol was as popular as visiting local pubs. Some of the interviewees recalled the daily trip to the local pub to buy dinner beer

I remember some of the older boys going round to fetch the supper beer – which was a pint of beer for tuppence, you see they [parents] had a glass each out of that for their supper. But none of us were ever allowed to taste it. But the older boys were allowed to go round with the jug in those days – there wasn’t bottled stuff and things you see. And it was considered dreadful for a younger person to be in a pub you see – so that it was only the older ones who were allowed to fetch the supper beer – or perhaps my mother or father would fetch it themselves you know.’63

Drinking beer with the evening meal seems to have been a common feature of working-class life for both men and women but it was mainly men who went to the pub regularly in the evenings. One interviewee, a man from Essex, was asked if his mother and father drank beer with their evening meal. He only recalled his mother having a half pint of porter every evening with supper and instead his father would visit the local pub in the evenings. When asked if his mother and father ever went to the pub together, he replied that in his town women did not enter pubs and instead were more likely to consume alcohol at home.64

In a study of pubs in York in 1900, Seebohm Rowntree observed the gender differences of customers who frequented different pubs in the town.65 He noted marked variations in the numbers of men and women who went to different pubs located in working-class districts. In the slums and in poorer working-class areas, women drinkers were a more visible presence within pubs. Yet in more affluent working-class areas, women still visited pubs but many went only to fetch the dinner beer. Rowntree noted that these women were ‘all respectably dressed and of cleanly appearance’ and that within the pubs under observation ‘no cases of extreme drunkenness occurred’.66 Rowntree drew a distinction in terms of respectability between women who drank in pubs and those who drank at home. In those terms, it was not the act of drinking alcohol that challenged feminine norms but rather the location of alcohol consumption. This mattered less for men’s drinking behaviour which was governed by different social rules. Working class fathers’ drinking revolved around family life and daily routines. Drinking beer with dinner seems to have been common, as was visiting local pubs in the evenings. Interviewees from urban and rural regions of Britain recalled their fathers’ regularly going to local pubs and working men’s clubs to socialise and to conduct businessInterviewee (JF):

He’d [father] go out and have a drink because at those times—they used to do a lot of business in the pubs, you see, he’d meet different people in these pubs and they’d say, all right Bill, will you make me a suit you see and he’d meet them in these places … And they’d come into this boozer and just pay him a shilling or two shillings—whatever they could afford [for the suit]. Interviewer:

Did he stick to the same boozer?JF:

Oh no he went to several and then some evenings he went to whist drives and they were held at these public houses you know. And he’s probably go there perhaps one night or two nights a week.67

The Pubs and the People study focused on the pub as a social institution. The study listed the types of activities that people (mostly men) did in pubs. These included: drinking; smoking; playing cards; dominoes; darts and quoits; singing and listening to the piano; betting and talking about—sport, work, people, drinking, the weather, politics and ‘dirt’ (scandal). The pub was also a venue for a range of other activities such as weddings and funerals, trades union meetings, secret societies, finding work, crime and prostitution, sex and gambling.68 The study found that for most people in Bolton, ‘drink’ meant beer (usually the local beer known as ‘mild’) and that most drinkers’ preferences were motivated by price rather than quality, taste or fashion but again there were gender differences in consumption

Men are guided by price [of beer] first. Women, who often have men pay for them, go more for taste and the externals. It is more ‘respectable’ for women to drink bottled beer, mostly bottled stout or Guinness, seldom mild.69

In order to find out the reasons why people mainly drank beer, the researchers ran a questionnaire competition that offered financial incentives for consumer participation. The top reasons given for drinking beer were ‘social reasons’ followed by ‘health’. The health reasons were broken down into sub-categories

- General health-giving properties—24%

- Beneficial effects connected to work—17%

- Good effect on appetite—14%

- Laxative effect—10%

- Nourishing—6%

- Tonic—8%

- Valuable properties in malt and hops—6%

- Vitamins—6%

- Diuretic—2%

The researchers believed that many of the health reasons given by respondents were a direct result of brewers’ advertising and marketing tactics

Many people use the phrase ‘beer is best’. This is a clue to the large number of references to its health-giving properties; phrases like ‘it is body building’ – ‘picks a man up’ – are a direct reflection of brewers’ advertising. In the days before mass beer propaganda people drank considerably more than they do now. The history of the last hundred years of drinking in England is a history of decline. These [questionnaire responses] definitely show how advertising phrases intended to keep up consumption have become a part of pub-goers mental attitude to their beer. Beer more than anything else has to overcome guilt feelings. That is why advertising is simple, insistent, fond of superlatives, visual and often showing other people drinking the stuff, radiant with good cheer or good looks.70

The researchers concluded that consumers were caught in a trap between temperance and brewers’ propaganda, which sought to convince people that drinking was either harmful and sinful or healthy and good. Since the pub was such a central aspect of social life, people either consciously or subconsciously chose to believe the brewers hype. The notion that ‘beer is best’ had become a deeply ingrained and almost unconscious justification for consuming alcohol. Some of the respondents offered their personal reasons for drinking beer. One man aged 66 gave his reasons for drinking beer

… because it is a food, drink and medicine to me. My bowels work regular as clockwork and I think that is the key to health. Also lightening affects me a lot, I get such a thirst from lightening and full of pins and needles, if I drink water from a tap its worse.71

Aside from health reasons, the study also considered why men in particular drank beer and found that many of these reasons related to concepts of masculinity and heterosexuality. Some men stated that beer ‘put lead in their pencil’ or alluded to their drinking habits having a positive effect on their sex lives and even improving their marriages. When asked why he went to the pub and drank beer, one man aged 25, described as a ‘shop assistant type’ replied ‘What else can a chap do in a one-eyed hole like this, he’d go off his chump if there were no ale, pictures and tarts.’72 This explanation perhaps comes closest to situating beer as an escape or a distraction from the monotony of men’s daily lives. The idea that beer consumption somehow boosted masculinity and aided sexual function is not something that could be directly attributed to the effects of brewers’ marketing tactics. It could have arisen from the masculine environment of the pub and from the ways in which beer was consumed. Most working-class men drank the local draught beer (‘mild’ or ‘best’) in either pints or gills (quarter of a pint) and this distinguished them from women who drank stout, Guinness or bottled beers. It also made ‘mild’ a ‘man’s drink’ that was therefore imbued with masculine qualities. Add to this the largely male environment of the pub—particularly during weeknight evenings when men would ‘escape’ the home for a couple of pints—and it is hardly surprising that the consumption of beer became associated with an idealised view of male heterosexuality. Many of the male drinkers in the Worktown study were undoubtedly husbands who ‘went home to the wife’ at night and therefore it still fell within the scope of ‘respectable’ drinking if beer consumption was viewed as enhancing rather than diminishing their conjugal roles.

The masculine aspect of beer drinking is also evident in The Edwardians study. Most interviewees stated that their fathers drank moderately—one or two pints at most, and few recalled their fathers being drunk. Some also stated that their father would only visit local pubs at the weekends or in the evenings when finances permitted and instead much of their father’s drinking was confined to the home. In a study of late Victorian working-class life, Meacham argues that working-class men were divided between teetotallers who stayed at home in the evenings and beer drinkers that went to the pub for a pint or two in the evening.73 Meacham also believes that working-class men preferred to spend their leisure time in the company of other men and highlights the importance of working men’s clubs, which grew in popularity in the late nineteenth century as places where working men could meet, socialise and drink

There can be little doubt that a working man of moderation, who spent his leisure hours in a well-managed and generally reputable club, was contributing not only to his personal enjoyment but to his neighbourhood image as a respectable and responsible member of the community.74

Although this acknowledges the importance of sociable drinking within working men’s clubs and pubs in terms of cultivating and reinforcing ideas about masculinity the analysis misses the significance of domestic drinking where men and women drank together. Some of The Edwardians interviewees recalled their parents drinking at home, particularly in regions where it was considered socially unacceptable for women to drink in pubsInterviewer (I):

What about your mother, did she like a drink?Interviewee (A):

No.I:

She never went with him [father] to the pub?A:

Oh, good gracious me, not in those days!I:

Respectable women didn’t?A:

No.I:

Do you think that none of your mother’s friends ever went, either, the people she knew, they wouldn’t have gone along?A:

I think that the people my mother associated with would not have gone to a public house.I:

If they wanted a drink anywhere, how do you think they got one?A:

We wouldn’t have gone, but Father might have gone down to what is commonly known as The Rats Hole—it was known as The Rats Hole always has been—and he would have taken a jug down and brought a jug of beer back home.I:

And they’d have a drink together?A:

Yes.75

In some regions women were not as constrained by gender norms. One of the interviewees recalled how her mother and other local women met every Monday and had a drink together. The interviewee was born in 1898 and grew up as part of a large working-class family in London

Well on the Monday – she had a few coppers so her and a lot of women used to go out – mother’s day they used to call Monday. And they’d dance down in the ground in the building, you know. They’d enjoy themselves. My mother used to play a mouth organ. And we always knew – Monday, oh my mother’d always have a sweet for me when I came home from school but we always knew when Monday came what to expect. No arguments – people’d be happy, all the neighbours, you know, but my mother didn’t mix up with them a lot but it was Monday [and] they seemed to go out and have a drink together. They’d put all their coppers together and they’d have this drink between them and – they never used to get drunk, never had that money. But they’d have perhaps one or two drinks, come back and start dancing. Enjoying themselves.76

‘Mother’s day’ was a weekly gathering of local women, which involved a trip to the pub followed by music and dancing in the streets. Few of the other interviewees talked of their mothers drinking publicly in this way. Yet this woman made it clear that in her community, it was customary for the local women to get together once a week and have a drink. Perhaps in some working-class areas of London this type of celebratory drinking was considered normal for women. Yet the majority of interviews described working-class women either drinking at home or to going to the pub in the company of husbands or other male family membersInterviewer (I):

You told me your mum and dad used to go out for a drink?Interviewee (LB):

Oh yes. Yes. That was their treat—yes.I:

In those days were women allowed to go in pubs?LB:

Oh yes. Yes. Yes. The first place—there was—it’s a little place—I don’t know whether it’s still there—It was called The Money up Hodge Lane and—they used to have a sing-song of a Saturday night.I:

There was no prejudice against women going?LB:

Oh no—none at all. And—they used to have a sing-song of a Saturday night.77

In some working-class communities, it was considered socially acceptable for women and children to go to local pubs to obtain alcohol for home consumption. One interviewee born in Dorset in 1904 remembered her grandmother’s drinking habits and how she used to regularly visit the local pub to get beer to take home and drink with friends

Now my grandma – I tell you – when I was – how old was I – about twelve or thirteen I suppose – oh she must have been – must have been going on a long time before that, but I can particularly remember – you know they used to wear the capes, the old ladies, and a little bonnet with a – rose in the – or something in the front, and tied under the chin? Well she used to put her cloak on, take her little jug, go down to what used to be The Prince of Wales. Go down there and get a – half pint of stout. Go home, take her bit of cheese, and she used to go down to a friend’s called Mrs Tizzard – Emma we called her. And she used to take her bread and cheese and her half pint of stout down there and have that there with Emma. I can see her now. With her cloak and her little jug, you know.78

Stout was a popular drink among women, particularly during pregnancy and after childbirth. This popularity could have stemmed from advertising which promoted the health-giving and nutritious properties of beers and stout (see Figs. 11.1 and 11.2).

One interviewee who was born in Essex in 1881 recalled his mother drinking stout during pregnancy, even though his father was a teetotaller.81 Another interviewee who grew up in London had similar memories of her mother drinking small quantities of stout on a regular basis

I remember mother used to have a bottle – a quart bottle of stout – very reasonable in those days – used to last her a week. She used to have a little drop in a glass like that – and then of course we’d all say to her can we have a little drop.82

Bottles of stout and jugs of beer from pubs were not the only ways that working-class women obtained alcohol. It also seemed to be common to brew beer and herbal wines for home consumption. Most of the working-class interviewees were asked if either of their parents brewed or fermented their own homemade beer or wine

She [mother] used to make beer. Homemade beer in a big yellow mug and bottle. And have nettles or whatever it was drying on the line. Drying on the line, nettles and herbs ready for her beer and sometimes she used to tell me before I was born she used to sell it on a Sunday morning to people who came knocking at the door. They loved it. That’s when we lived in Manchester before they came up to Salford.83

Brewing and selling beer for home consumption may also have been a way to supplement income. Despite regional differences, working-class women from urban and rural areas, made their own beer and wine. In some cases, women made non-alcoholic ‘botanic’ or herb beer and wine that was drunk by the whole family as a ‘tonic’ or as a ‘treat’ but many brewed and fermented alcoholic drinks that were consumed regularlyInterviewer (I):

Do you remember your family brewing beer at all?Interviewee (EP):

Herb beer. Everybody brewed herb beer in them days. That was all made of stinging nettles and various seed cones and you had to tie the cork down with wire else it’d blow off. That was always for Sunday dinner.I:

What was it like?EP:

Very good. Wish I had some of it now.84

By producing alcoholic drinks that could be consumed at home, working-class women could overcome some of the barriers to drinking posed by gender values. It was perhaps also cheaper to make beer and wine than to buy it from local pubs or licensed grocers. Aside from thrift, there was more privacy in making and consuming alcohol at home and therefore this could have been an attractive option for women who wanted to drink. Yet there was a certain degree of skill involved in making home brew and the cost of equipment and ingredients would have mattered. In A Plain Cookery Book for the Working Classes , published in 1854, there were instructions for making elder wine and homemade beer.85 Successful fermenting and brewing were dependent upon a fresh supply of clean water, adequate equipment with the space to house it and of course suitable ingredients. Making homemade beer and wine also took time so given these factors and the constraints of money, space and time faced by many working-class families it is surprising that so many of the interviewees recalled their mothers’ making alcoholic drinks. As Mitchell notes, for many working-class families, ‘dinner beer’ was a staple feature of the teatime meal, especially for men coming home from work in the evenings.86 It may be that the production of homemade alcohol supplemented the beer bought from pubs and if home brew was sold, it added to the household income.