To look backward is to be reminded that manufacturing decline is not only about numbers or jobs; is about the spaces where people create meaning through labor.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The metaphor of loss, of productive spaces falling silent, of trades once central to civic identity reduced to hollow shells, is not new. Ancient societies confronted the disappearance of their own workshops and the consequences rippled across their political, cultural, and economic systems.

To examine the ancient record is not to indulge in a facile analogy. Each society faced its own constellation of pressures, from war to environmental catastrophe to shifting trade routes. Yet the recurring pattern of productive decline illuminates the universality of the workshop as both a material and symbolic cornerstone of collective life. By looking across Athens, Rome, Egypt, Crete, and Byzantium, one can discern structural weaknesses that reemerge whenever the integrity of skilled labor collapses.

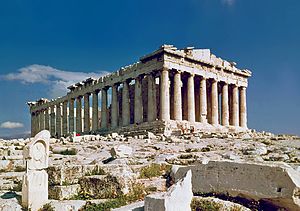

Athens and the Disruption of Craft after the Peloponnesian War

Athens in the fifth century BCE was celebrated not only for its political innovations but also for its flourishing of artisanal labor. The Kerameikos district produced pottery of extraordinary reach, its amphorae and kylikes discovered across the Mediterranean. Shipbuilding yards equipped the naval power that secured the empire’s revenues. These industries created an economic backbone that sustained the city’s democratic experiment.

The Peloponnesian War shattered this foundation. Spartan victory severed trade routes and stripped Athens of tribute revenues. Artisans lost markets abroad, and workshops closed as domestic demand contracted. Potters who once exported their wares to Sicily and Egypt found themselves without buyers. The once dynamic maritime economy collapsed under the dual pressures of war indemnities and social instability.1

The symbolic blow was profound. Athens, once the “school of Hellas,” lost not only power but also the material expression of its cultural confidence. The decline of artisan guilds mirrored the erosion of civic pride.

In this sense, the vanishing workshop was not only an economic reality but a cultural trauma. The empty spaces of craft reflected the hollowing of democratic energy, and Athens never fully regained the confidence that had defined its golden age.

Rome and the Decline of the Artisan Economy

The Roman Empire’s grandeur was built in part on the labor of its workshops. Blacksmiths, potters, and carpenters produced goods that defined daily life. Yet by the third and fourth centuries CE, cracks were visible. Independent artisans, long vital to urban economies, were increasingly bound into compulsory guilds. Membership was hereditary, escape was forbidden, and the vitality of craftsmanship withered under the weight of coercion.2

At the same time, Rome’s reliance on slave labor undermined incentives for free artisans. Imports from provinces flooded the capital with cheap goods, eroding local production. Workshops that once symbolized the dignity of urban labor were reduced to state-controlled service units. The dynamism of Roman cities suffered as small producers lost autonomy and creativity. This decline was more than economic. It altered social identity. The urban artisan, once a figure of civic integration, was marginalized.

Egypt’s Tomb Builders and the First Recorded Strike

In Egypt’s New Kingdom, the workers of Deir el-Medina enjoyed an unusual prestige. Tasked with building royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings, they were highly skilled and carefully provisioned. Yet in 1159 BCE, their rations failed to arrive. Rather than endure hunger, the workers ceased labor and staged what is often recognized as the first recorded strike in human history.3

The disruption was not only economic but also symbolic. To halt work on royal tombs was to halt the machinery of divine kingship itself. The strike revealed that even in highly centralized states, the neglect of labor could paralyze the core of political ideology.

The artisans of Deir el-Medina demonstrated that the workshop was not simply a site of production but a site of political power. Their protest represented a direct challenge to pharaonic authority, signaling that no ruler could command legitimacy without honoring the covenant of sustenance.

What makes this episode striking is how the failure originated in bureaucratic neglect rather than foreign conquest or natural disaster. A state that prided itself on order faltered in its simplest duty: feeding the very workers who gave permanence to its kings through tomb construction.

The vanishing workshop here thus carried multiple meanings. It marked the interruption of labor, the exposure of state weakness, and the first stirrings of labor resistance recorded in history. Its resonance lies not only in its uniqueness but in the timelessness of its lesson.

The Collapse of Minoan Craft Economies

The island of Crete in the second millennium BCE was a center of artisanal brilliance. Minoan frescoes, metalwork, and ceramics testify to the skill of its workshops. These products were not only consumed locally but circulated across the Aegean, making Crete a hub of cultural and commercial exchange.

The eruption of Thera around 1600 BCE, combined with subsequent Mycenaean encroachment, devastated this economy. Palatial centers that coordinated artisanal labor were destroyed, and with them the networks that sustained production. Workshops disappeared almost overnight. Skilled laborers either perished or were absorbed into Mycenaean systems that lacked the same vibrancy. The collapse was total.

Unlike Athens or Rome, where workshops lingered in diminished form, the Minoan case illustrates how catastrophe can erase an entire tradition of craft. The vanishing workshop here was not symbolic but literal, a rupture in cultural memory. What had been a flourishing artisan culture became an archaeological silence, leaving us only fragments to reconstruct its lost vitality.4

Byzantium and the Decline of Silk Production

In the sixth century CE, Byzantium achieved a remarkable coup by smuggling silkworms from China. This act allowed the empire to become a global powerhouse of silk production, rivaling long-established Eastern monopolies. For centuries, Byzantine silk workshops produced garments that adorned emperors, clergy, and elites across Europe and the Mediterranean.

By the fourteenth century, however, the empire’s position weakened. The encroachment of Ottoman power disrupted trade routes, while Italian city-states like Venice and Genoa seized opportunities to dominate markets. Byzantine producers could not compete with these dynamic rivals.

Workshops closed as demand shifted. Political instability further eroded capacity, and by the time Constantinople fell in 1453, the once mighty silk industry had largely vanished. Its disappearance marked not only an economic collapse but also a loss of imperial prestige.

The decline of Byzantine silk demonstrates how political weakness translates into economic erosion. Workshops vanished not because artisans lacked skill but because states failed to secure conditions in which their craft could survive.5

Conclusion

The vanishing workshop is a recurring motif in history. In Athens, it was war and defeat that silenced artisans. In Rome, coercion and reliance on external labor hollowed out local economies. In Egypt, state neglect led to protest that reverberated through divine kingship. In Crete, catastrophe erased an entire craft tradition. In Byzantium, geopolitical weakness dismantled a once-proud industry.

Each case offers a variation on the same theme: the fragility of skilled labor as a foundation of civic life. Workshops are not merely economic units. They embody culture, sustain identity, and anchor political legitimacy.

To look backward is to be reminded that manufacturing decline is not only about numbers or jobs; is about the spaces where people create meaning through labor. The silence of ancient workshops warns that their disappearance always carries costs measured in more than lost output.

In that silence, societies discover the true price of neglect. What vanishes is not just production but the human spirit that animates it, a reminder that every empty workshop is a political statement written in absence.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Donald Kagan, The Peloponnesian War (New York: Viking Press, 2003), 457–462.

- Peter Garnsey and Richard Saller, The Roman Empire: Economy, Society and Culture (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987), 102–108.

- John Romer, Ancient Lives: The Story of the Pharaoh’s Tombmakers (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1994), 73–77.

- Sinclair Hood, The Arts in Prehistoric Greece (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1953), 51–58.

- Angeliki Laiou, ed., The Economic History of Byzantium: From the Seventh through the Fifteenth Century (Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks, 2002), 1121–1134.

Bibliography

- Garnsey, Peter, and Richard Saller. The Roman Empire: Economy, Society and Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987.

- Hood, Sinclair. The Arts in Prehistoric Greece. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1953.

- Kagan, Donald. The Peloponnesian War. New York: Viking Press, 2003.

- Laiou, Angeliki, ed. The Economic History of Byzantium: From the Seventh through the Fifteenth Century. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks, 2002.

- Romer, John. Ancient Lives: The Story of the Pharaoh’s Tombmakers. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1994.

Originally published by Brewminate, 09.08.2025 under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.