Weimar’s emergency provisions were not imposed from outside the constitutional system but were written into it as hopeful safeguards against instability

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Elections, Federalism, and Democratic Constraint

Elections are often treated as the visible core of democratic life, the recurring moment when citizens are invited to authorize those who govern them. Yet elections do not operate in isolation. Their democratic force depends on the institutional environment in which they are conducted, administered, and enforced. In federal systems, that environment is deliberately fragmented. Authority is distributed across multiple levels of government so that no single actor can monopolize political legitimacy. Elections constrain power only when this dispersion is preserved. When it is overridden, voting may continue while democracy quietly weakens.

Federalism functions as a structural restraint on executive domination in ways that are often misunderstood or undervalued. By assigning responsibility for elections, policing, and internal administration to subnational units, federal systems prevent the consolidation of coercive and administrative power at the center. This distribution creates multiple veto points and overlapping jurisdictions, forcing negotiation rather than command. Friction, redundancy, and delay are not defects of federal democracy but safeguards against capture. Locally administered elections are harder to standardize under partisan control, harder to manipulate uniformly, and harder to subordinate to executive will. Federalism does not ensure democratic virtue, but it preserves the institutional conditions under which democratic contestation remains possible.

The Weimar Republic illustrates how fragile this balance can be when emergency powers are introduced into a federal constitutional order. The Weimar Constitution preserved elections, representative institutions, and state autonomy on paper, yet embedded within it was a mechanism that allowed executive authority to bypass those safeguards in moments of crisis. Article 48 was designed to address exceptional threats, not to replace ordinary governance. Its repeated invocation transformed emergency authority into routine practice, shifting real power away from elected bodies and subnational governments while preserving the outward forms of democracy.

What follows argues that Weimar democracy collapsed not when elections ended, but when federal control over elections and internal security was overridden by executive decree. The decisive rupture occurred as state governments lost effective authority over policing, public order, and electoral administration, leaving democratic procedures exposed to centralized coercion. By tracing the erosion of Länder autonomy, the normalization of emergency governance, and the gradual transformation of elections into managed confirmations between 1930 and 1933, this study demonstrates how federal systems fail democratically from within. Elections persisted, ballots were cast, and governments were formed, yet the capacity of elections to constrain power had already been destroyed. Weimar’s lesson is structural and enduring. Democracy depends not only on voting, but on who controls the conditions under which voting has consequences.

The Weimar Constitutional System: Federalism, Elections, and State Autonomy

The Weimar Republic was established in 1919 as the constitutional successor to the German Empire, combining elements of parliamentary democracy, federal structure, and strong executive authority. Unlike a unitary parliamentary system, Weimar Germany retained the Länder (states) as semi-autonomous units with their own parliaments (Landtage) and administrative authority, including significant responsibility for running elections and maintaining public order. The national legislature (Reichstag) was elected by universal, equal, direct, and secret suffrage under proportional representation, reflecting one of the most progressive electoral systems of its time. This democratic foundation, however, was embedded within a constitutional framework that also concentrated unusual powers in a directly elected president, creating latent tension between federal autonomy and centralized authority.

Under the Weimar Constitution, the federal structure was embodied not only in the continued existence of Länder governments but also in the Reichsrat, the upper chamber representing state interests at the national level. Through the Reichsrat, states possessed a formal mechanism to influence legislation and resist unilateral action by the Reich government. State elections for Landtage occurred regularly, reinforcing the principle that democratic legitimacy flowed upward from local and regional constituencies. In theory, this system ensured that electoral authority and internal governance were dispersed, preventing any single institution from monopolizing political power.

Nevertheless, the Weimar Constitution also contained provisions that undermined this balance when activated. Article 48 granted the Reich President the authority to take extraordinary measures to restore public order and security, including the suspension of civil liberties and the deployment of armed force. Although framed as a safeguard against existential threats, the provision lacked clear substantive or temporal limits. Its ambiguity allowed emergency authority to coexist with, and increasingly override, ordinary constitutional governance. What was designed as an exception became a parallel mode of rule.

This emergency mechanism created a profound structural vulnerability in Weimar federalism. As Article 48 was invoked with increasing frequency, the national executive bypassed both the Reichstag and state governments, ruling by decree rather than legislation. States formally retained responsibility for policing, elections, and administration, but these competencies became contingent on presidential tolerance. Federal autonomy persisted on paper, yet in practice it was increasingly subordinated to centralized emergency authority. The constitutional hierarchy was inverted: state powers survived only insofar as they did not conflict with executive decrees issued in the name of security.

The normalization of emergency governance had direct consequences for electoral sovereignty at the state level. Elections continued to be held, but the institutional conditions necessary for their independence eroded. When policing, assembly, and enforcement could be overridden from the center, state governments lost the ability to guarantee free political competition. Electoral administration became vulnerable to coercion, intimidation, and federal intervention, even without the formal suspension of voting. In this way, the erosion of state autonomy preceded and enabled the hollowing out of democratic choice. Federalism did not collapse through repeal, but through conditional subordination.

By preserving federal structures in form while hollowing them out in practice, the Weimar Constitution allowed democratic erosion to proceed without constitutional rupture. State elections, local parliaments, and federal institutions continued to exist, masking the transfer of real authority to the executive center. This disjunction between appearance and function proved fatal. When Adolf Hitler later moved to consolidate total control, the mechanisms required to override state autonomy were already normalized. The federal system had not failed suddenly in 1933; it had been quietly dismantled through emergency rule long before democracy formally ended.

Article 48: Emergency Powers and Constitutional Ambiguity

Article 48 of the Weimar Constitution was conceived as a safeguard against extraordinary threats to public order, not as a substitute for democratic governance. It authorized the Reich President to suspend civil liberties and issue emergency decrees when “public safety and order” were seriously disturbed or endangered. In theory, these powers were to be exercised sparingly and temporarily, with the Reichstag retaining the authority to revoke emergency measures. The provision reflected a widely shared fear in postwar Germany that the fragile republic might not survive internal collapse or violent insurrection without a mechanism for decisive executive action.

Yet Article 48 was marked by a profound constitutional ambiguity that proved far more consequential than its authors anticipated. The Constitution provided no clear definition of what constituted an emergency, no fixed duration for emergency rule, and no substantive criteria to distinguish temporary necessity from political convenience. While the Reichstag could theoretically overturn emergency decrees, this safeguard depended on parliamentary cohesion, majority formation, and procedural functionality. As party fragmentation deepened and legislative paralysis became routine, the practical ability of parliament to check presidential power diminished sharply. Emergency authority ceased to operate as an exception to constitutional order and instead emerged as a parallel and increasingly dominant mode of governance.

This ambiguity proved fatal because it allowed emergency powers to be normalized without overt constitutional violation. Presidents Friedrich Ebert and Paul von Hindenburg both relied on Article 48 with increasing frequency, establishing precedent long before Adolf Hitler entered office. What began as crisis management gradually displaced ordinary legislative processes. Decrees replaced laws, executive judgment replaced parliamentary deliberation, and constitutional restraint was reframed as impractical idealism. Importantly, none of this required the suspension of elections or the dissolution of federal institutions. The constitutional system continued to function outwardly even as its democratic core eroded.

Article 48 illustrates how legal mechanisms intended to protect democracy can be repurposed to undermine it from within. By embedding extraordinary authority into the constitutional framework without robust temporal or procedural limits, Weimar created a pathway for executive domination that remained formally lawful. Emergency governance became compatible with constitutional continuity, allowing power to concentrate without triggering institutional alarm. Elections continued, rights were periodically restored, and federal structures persisted in appearance, fostering the illusion of stability. Yet the balance of power had shifted decisively toward the executive. The danger of Article 48 was not that it authorized dictatorship outright, but that it made authoritarian governance seem normal, legal, and reversible even as democratic constraint steadily disappeared.

Crisis Governance becomes Routine: 1930–1932

By 1930, emergency governance in the Weimar Republic was no longer an extraordinary response to isolated threats but a normalized mode of rule. Parliamentary coalitions had fractured under the pressures of economic collapse, mass unemployment, and political radicalization. The Great Depression intensified existing structural weaknesses, making legislative compromise increasingly difficult. Rather than serving as a temporary bridge back to parliamentary governance, Article 48 became the primary mechanism through which the Reich government functioned. Elections continued to be held, but policy was increasingly made outside the legislative process.

The collapse of parliamentary government was institutionalized under Chancellor Heinrich Brüning, whose cabinets governed almost entirely by presidential decree. Brüning lacked a stable majority in the Reichstag, yet remained in office through the personal support of President Paul von Hindenburg and the routine invocation of Article 48. Budgets, taxation policy, welfare reductions, and labor regulations were enacted without parliamentary approval, fundamentally reversing the constitutional relationship between legislature and executive. When deputies attempted to challenge decrees, the executive response was not compromise but dissolution of the Reichstag and the calling of new elections. Parliamentary accountability was transformed into electoral exhaustion, as voters were repeatedly sent to the polls without gaining meaningful influence over governance.

This reliance on emergency powers transformed elections into instruments of pressure rather than mechanisms of choice. Reichstag elections in 1930 and 1932 were framed as plebiscites on executive authority rather than contests over policy alternatives. Voters were repeatedly told that parliamentary government was incapable of addressing crisis and that decisive leadership was required. Electoral outcomes no longer determined who governed or how policy was made. Instead, they were used retroactively to justify continued rule by decree, reinforcing the perception that voting could register frustration or approval but could not redirect political power.

Crisis governance also altered the relationship between the Reich and the states in ways that proved decisive for democratic collapse. Emergency decrees increasingly bypassed Länder governments, overriding state authority in matters of policing, public assembly, and internal security. Federal intervention, once constitutionally exceptional, became routine administrative practice. As the Reich assumed greater control over enforcement mechanisms, state governments lost their capacity to regulate political violence, protect opposition activity, or ensure fair electoral conditions. While state institutions remained formally intact, their practical autonomy eroded, leaving elections increasingly exposed to centralized coercion and intimidation.

By 1932, the Weimar Republic had entered a condition of permanent exception. The distinction between constitutional rule and emergency governance had effectively collapsed. Elections persisted, legislatures met, and the constitution remained formally in force, yet the substance of democratic accountability had already been displaced. Executive authority operated continuously through decree, and federal safeguards had been hollowed out. Crisis no longer justified emergency rule. Emergency rule had become the system itself.

The Bypassing of State Authority: Federalism Undermined

The decisive erosion of Weimar democracy occurred not at the ballot box, but in the systematic bypassing of state authority that had once anchored electoral and administrative autonomy. Federalism in the Weimar system was designed precisely to prevent the concentration of coercive and administrative power at the center by dispersing control over policing, public order, and election administration among the Länder. These state governments were meant to serve as independent guarantors of political pluralism and electoral integrity. Yet as emergency governance became normalized, the Reich increasingly treated state autonomy not as a constitutional safeguard but as an impediment to decisive action. Presidential decrees intervened directly in state affairs, subordinating regional governments to centralized command without formally abolishing federal structures or repealing constitutional protections.

This process unfolded through legal mechanisms that preserved constitutional appearance while hollowing out substance. Under the pretext of restoring order, the Reich intervened in state policing, restricted public assembly, and imposed uniform enforcement standards across diverse political landscapes. State governments retained nominal authority, but their decisions could be overridden at will by executive decree. The result was a conditional federalism in which state powers existed only so long as they aligned with central priorities. Autonomy became provisional, revocable, and dependent on executive discretion.

The most consequential impact of this shift was felt in the administration of elections. Free and competitive elections depend not only on formal rules but on the capacity of local authorities to enforce them impartially. As the Reich assumed control over policing and security, states lost the ability to protect opposition parties, regulate political violence, and ensure equal access to public space. Electoral procedures remained intact, but the conditions necessary for meaningful choice deteriorated. Voting persisted, yet it occurred within an environment increasingly shaped by centralized coercion rather than local accountability.

By the time Adolf Hitler entered office in 1933, the infrastructure required for total national control was already firmly established. Federalism had not been dismantled through constitutional repeal or public confrontation, but neutralized through administrative override and legal precedent. The Reich possessed the authority, enforcement capacity, and normalized emergency practices necessary to subordinate the Länder rapidly and with minimal resistance. When the final consolidation of power occurred, it did not require the abolition of elections or the formal destruction of federal institutions. Those structures remained, but their autonomy had already been stripped away. Democracy collapsed not because voting ended, but because the federal system that gave elections their constraining force had already been rendered ineffective.

Elections under Duress: Intimidation, Central Oversight, and Managed Outcomes

By the early 1930s, elections in Weimar Germany continued to occur with regularity, yet they unfolded under conditions increasingly hostile to democratic choice. Political violence escalated dramatically, with street fighting, intimidation, and targeted harassment becoming routine features of electoral life. Paramilitary organizations, most notably the National Socialist Sturmabteilung (SA), disrupted opposition meetings, intimidated voters, and created an atmosphere in which participation carried physical risk. Elections remained formally free, but they were no longer conducted in an environment of equal security or fair competition.

The erosion of state authority over policing proved decisive in this transformation. As the Reich assumed greater control over internal security through emergency decrees, local governments lost the capacity to regulate violence impartially. In many regions, state officials were pressured to tolerate or cooperate with paramilitary forces aligned with nationally favored movements, while opposition parties found their meetings restricted or broken up in the name of public order. Police forces that had once been answerable to elected state governments increasingly took direction from central authorities, blurring the line between law enforcement and political enforcement. Neutrality eroded not through formal orders alone, but through institutional signaling that certain actors enjoyed protection while others did not.

Central oversight further altered electoral dynamics by redefining the boundaries of permissible political activity. Emergency decrees limited public assembly, censored press outlets, and curtailed campaigning under expansive claims of security necessity. These restrictions were applied unevenly, often disadvantaging parties that challenged executive authority while allowing favored movements greater latitude. Administrative discretion replaced uniform legal application. Electoral law remained on the books, but its enforcement reflected political priorities rather than constitutional equality. Elections continued procedurally, yet the regulatory environment in which they occurred increasingly predetermined whose voices could be heard.

Intimidation operated not only through violence, but through the normalization of fear. Voters were repeatedly told that democratic procedures were incapable of resolving crisis and that instability would persist unless strong leadership prevailed. Campaign rhetoric emphasized existential threats, internal enemies, and national humiliation, framing elections as moments of emergency decision rather than deliberative choice. Under such conditions, voting became less an expression of preference than a response to pressure, anxiety, and constrained alternatives.

These dynamics transformed elections into managed outcomes rather than open contests. Although multiple parties continued to appear on ballots and voter turnout remained high, the range of meaningful political choice narrowed steadily. Electoral success increasingly reflected the capacity to dominate public space, command administrative tolerance, and align with executive authority rather than persuade freely organized citizens. Opposition parties faced structural disadvantages that no amount of formal legality could overcome. Elections still conferred legitimacy, but that legitimacy flowed predictably toward forces already empowered by centralized control and protected by the state.

The Weimar experience demonstrates that elections need not be canceled to be emptied of democratic content. When intimidation shapes participation, when central oversight replaces local neutrality, and when enforcement serves power rather than law, voting becomes a ritual conducted under duress. The machinery of democracy continues to operate, but its function is reversed. Instead of constraining authority, elections validate it. In such conditions, democratic collapse does not arrive with the abolition of ballots, but with their transformation into instruments of confirmation rather than choice.

Hitler’s Appointment: Dictatorship through Constitutional Means

Hitler’s appointment as chancellor on January 30, 1933, did not occur through a revolutionary seizure of power or the visible collapse of constitutional order. It emerged from within a system that still held elections, maintained formal institutions, and claimed legal continuity. The Weimar Constitution remained in force, political parties were not yet abolished, and parliamentary procedures had not been formally suspended. Yet the democratic substance of the republic had already been gravely weakened. Elections no longer constrained executive authority, federal autonomy had been subordinated to centralized decree, and emergency governance had become routine. Hitler’s appointment was not a rupture, but the final step in a long process of constitutional erosion that had already hollowed out democratic restraint.

The decision to appoint Hitler was made entirely within the existing constitutional framework by President Paul von Hindenburg, relying on precedents established during years of rule by emergency decree. The chancellorship itself was not designed as an authoritarian office, but by 1933 it operated in an environment transformed by executive dominance. Parliamentary consent had been rendered optional, coalition-building unnecessary, and legislative resistance ineffective. Governing by decree under Article 48 had normalized executive supremacy, while repeated dissolutions of the Reichstag had exhausted parliamentary legitimacy. Hitler did not need to overthrow this system. He entered a political order already conditioned to accept centralized authority as necessary and lawful.

Crucially, Hitler’s consolidation of power depended on the prior erosion of federalism rather than its immediate abolition. The Länder continued to exist, and state governments formally retained their constitutional roles. Yet their authority over policing, public order, and electoral administration had already been compromised by emergency intervention. When the Reich asserted control, it encountered little institutional resistance because the legal mechanisms for override were already established. Federalism was not dismantled through confrontation, but neutralized through precedent. State autonomy survived only nominally, leaving no effective barrier to national consolidation.

Elections continued after Hitler’s appointment, but their meaning had shifted decisively. The March 1933 Reichstag election was conducted amid widespread repression, censorship, and intimidation that rendered genuine competition impossible. Opposition parties were harassed, meetings disrupted, and press outlets silenced, all under the guise of emergency security. Yet the election itself was not annulled. Its function was not to determine power, but to legitimate it. The subsequent passage of the Enabling Act followed constitutional procedures even as it suspended democratic governance, marking the formal end of parliamentary constraint without formally abolishing the republic.

Hitler’s dictatorship emerged not in defiance of constitutional procedure, but through its systematic exploitation. The Weimar Republic did not fall because its constitution was ignored, but because its emergency provisions, weakened federal safeguards, and hollowed electoral system were used exactly as they had been allowed to operate. Democracy ended before dictatorship was openly declared. By the time authoritarian rule was formalized, elections had already been transformed into instruments of legitimacy rather than limits on power. The transition was legal, incremental, and devastatingly effective precisely because it preserved the appearance of constitutional continuity while destroying its democratic core.

Structural Lessons: Federal Collapse as Democratic Collapse

The Weimar experience demonstrates that democratic collapse in federal systems rarely begins with the abolition of elections. It begins with the erosion of the structures that give elections meaning. Federalism disperses authority not as a concession to regional identity, but as a safeguard against centralized domination. When control over policing, electoral administration, and public order is distributed among subnational governments, no single actor can easily convert electoral success into unchecked power. Weimar’s failure lay not in the existence of emergency authority itself, but in the gradual subordination of federal autonomy to executive discretion.

This pattern reveals a critical distinction between democratic form and democratic function. Elections may persist under centralized control, but without independent administrative environments they cease to constrain authority. In Weimar Germany, the weakening of state autonomy allowed national emergency powers to reshape political competition without formally violating constitutional procedures. Federal collapse preceded democratic collapse. Once the Länder lost their capacity to act as independent guarantors of electoral fairness, voting could be managed, pressured, and instrumentalized at the national level without overt constitutional rupture.

Comparative history reinforces this lesson with unsettling consistency. From the late Roman Republic to early modern absolutist states and twentieth-century authoritarian transitions, the decisive shift occurs when local control over political process is overridden in the name of efficiency, security, or national survival. Central authorities rarely need to cancel elections outright. It is sufficient to control who enforces electoral rules, who polices participation, who controls public space, and who adjudicates disputes. Federal systems are particularly vulnerable when emergency mechanisms allow the center to bypass subnational resistance while preserving constitutional appearances. The collapse does not arrive through spectacle, but through administration.

The structural warning of Weimar is enduring and precise. Democracies embedded in federal systems depend not only on constitutional text or electoral frequency, but on the continued independence of their constituent parts. When federal authority is overridden by executive decree, elections may survive indefinitely as procedures while dying as safeguards. Democratic collapse does not announce itself with the end of voting or the repeal of constitutions. It unfolds when the institutions that make voting meaningful are rendered subordinate, conditional, or irrelevant. At that point, the republic persists only as a shell, sustained by elections that legitimate power without restraining it.

Modern Implications: Emergency Powers and Federal Elections Today

The historical pattern seen in Weimar Germany, where emergency authority eroded federal autonomy and hollowed out the democratic content of elections, continues to have resonance in contemporary constitutional systems. Modern democracies, including federations like the United States, vest certain emergency powers in executives to address genuine crises, such as war, economic collapse, or public health emergencies. In the U.S., for example, the Constitution and federal law provide substantial emergency authority to the president, including through the National Emergencies Act and other statutory delegations that activate once a national emergency is declared. These powers can be broad and are often poorly defined in scope and duration, leaving them susceptible to expansion beyond their original crisis context.

Such expansive authority poses potential risks to electoral and federal processes because it can be used to centralize control over aspects of governance that in a federation are normally decentralized. Federal systems distribute key responsibilities, including election administration, policing, and voter registration, to subnational governments precisely to prevent any single actor from dominating political outcomes. When emergency powers allow a national executive to override or supplement those authorities, the balance between federal and state autonomy can be disrupted. For example, state and local officials in the U.S. administer and certify elections, and during recent crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic, many states exercised emergency powers to modify election procedures like voting deadlines or mail-in ballot rules to protect public health.

The debate around modern doctrines like the “independent state legislature theory” also underscores the ongoing danger of centralizing control over elections under legal or emergency pretenses. Although the U.S. Supreme Court recently rejected that theory, which would have concentrated election rule-making power in state legislatures against other institutional checks, the controversy highlights how constitutional interpretation itself can become a site of power struggle over who controls elections. Concentrating authority over election administration, whether via emergency powers or reinterpretation of constitutional clauses, can undermine the dispersion that helps protect democratic choice in a federal system.

The structural lesson from both historical cases like Weimar and present-day debates is clear: democracy in a federal context depends not only on the presence of elections but on the continued autonomy of subnational bodies in administering and safeguarding them. When emergency authority or centralized legal interpretations override federal balance, elections may continue in form but lose their capacity to constrain power. National crises do require extraordinary responses, but constitutional design must ensure that emergency powers are strictly bounded, subject to independent oversight, and time-limited so that electoral autonomy and federal safeguards remain intact. Without such boundaries, emergency mechanisms that are meant to preserve order risk becoming instruments of democratic erosion.

Conclusion: When Elections Continue and Democracy Is Already Gone

The Weimar Republic’s collapse provides a stark illustration of a central structural risk in federal systems: democracy can end not when elections are abolished, but when the institutions that give elections meaning are hollowed out. In Weimar Germany, elections continued even as executive authority increasingly bypassed parliamentary and federal constraints through emergency powers embedded in the constitutional order itself. This pattern demonstrates that voting alone does not constitute democratic governance. Elections constrain power only when they operate within an institutional framework that preserves independence, competition, and uncertainty of outcome. Once those conditions are eroded, elections persist as form while democracy disappears as function.

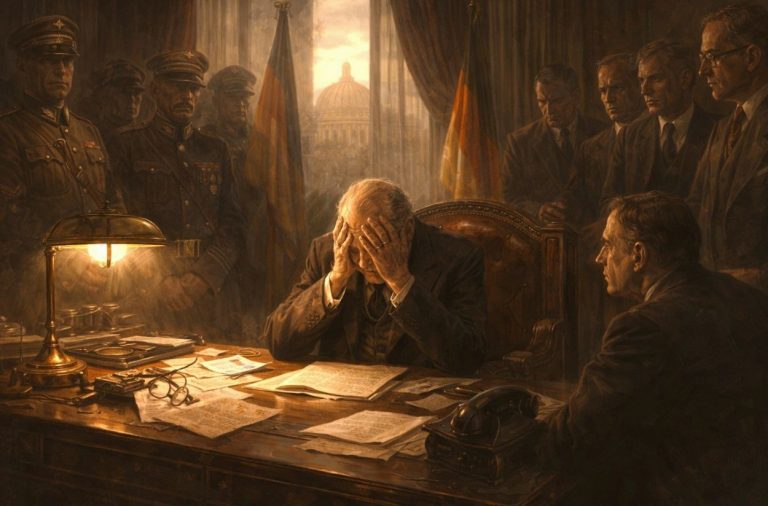

Weimar’s emergency provisions were not imposed from outside the constitutional system but were written into it as safeguards against instability. Article 48 authorized the president to take extraordinary measures to restore public order, including suspending civil liberties and governing by decree when public safety was deemed endangered. Crucially, these powers were framed as temporary and corrective, yet the constitution provided no clear limits on their duration or scope. As political crisis deepened, emergency decrees became routine instruments of governance rather than exceptional responses. Parliamentary oversight weakened as the Reichstag fragmented and was repeatedly dissolved, leaving little effective resistance to executive authority. Democratic mechanisms remained formally intact while losing their capacity to check or redirect power.

As federal balance unraveled, elections themselves were transformed. Voting continued, parties appeared on ballots, and turnout remained high, yet electoral outcomes no longer determined governance. The 1933 Reichstag election, conducted under conditions of repression, censorship, and intimidation, did not meaningfully alter political direction. Instead, it provided a veneer of popular endorsement for measures already underway. Subsequent legal actions, most notably the Enabling Act, completed the transfer of authority while preserving constitutional appearances. Democracy did not end through a single dramatic abolition. It expired incrementally as elections were repurposed from instruments of accountability into mechanisms of legitimation.

Weimar’s lesson is enduring and unsettling. Constitutional forms can survive even as democratic substance vanishes. Elections may continue indefinitely, yet once authority over their administration, policing, and enforcement is centralized, they cease to function as safeguards against domination. Democratic collapse need not announce itself through cancelled elections or dissolved legislatures. It can occur quietly, procedurally, and lawfully, leaving a republic intact in name while empty in reality.

Bibliography

- Arendt, Hannah. The Origins of Totalitarianism. New York: Harcourt, Brace & Company, 1951.

- Broszat, Martin. The Hitler State. New York: Longman, 1981.

- Caldwell, Peter C. Popular Sovereignty and the Crisis of German Constitutional Law. Durham: Duke University Press, 1997.

- Dyzenhaus, David. Legality and Legitimacy: Carl Schmitt, Hans Kelsen, and Hermann Heller in Weimar. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

- Evans, Richard J. The Coming of the Third Reich. New York: Penguin Press, 2003.

- Gunlicks, Arthur B. The Länder and German Federalism. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2003.

- Kershaw, Ian. Hitler: Hubris. New York: W. W. Norton, 1998.

- Linz, Juan J. The Breakdown of Democratic Regimes. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1978.

- Loewenstein, Karl. “Militant Democracy and Fundamental Rights.” American Political Science Review 31:3 (1937): 417–432.

- Mommsen, Hans. The Rise and Fall of Weimar Democracy. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996.

- Peukert, Detlev J. K. The Weimar Republic: The Crisis of Classical Modernity. New York: Hill and Wang, 1993.

- Schmitt, Carl. Political Theology: Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty. Translated by George Schwab. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

- The Weimar Constitution (1919), Article 48.

- Weitz, Eric D. Weimar Germany: Promise and Tragedy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007.

- Wolin, Sheldon S. Democracy Incorporated: Managed Democracy and the Specter of Inverted Totalitarianism. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.05.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.