The long European engagement with Greenland reveals a consistent pattern in the exercise of power over Arctic space.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: From Medieval Dominion to Imperial Object

Greenland’s place in European political imagination did not begin with early modern empire, yet it was profoundly reshaped by it. Medieval frameworks of dominion treated land as embedded within legal, religious, and communal orders, even at the edges of Latin Christendom. By the sixteenth century, however, European powers increasingly approached territory through a different lens, one shaped by mercantilism, imperial rivalry, and strategic calculation. Greenland’s transformation from a marginal but recognized polity into an imperial object reflects this broader shift in how sovereignty itself was understood and exercised.

Early modern Europe inherited medieval claims to Greenland without inheriting medieval assumptions about governance and obligation. Danish rulers invoked continuity with Norse settlement and ecclesiastical jurisdiction, but these claims were now filtered through emerging doctrines of possession and control. Authority no longer required dense settlement, reciprocal obligation, or sustained political community. Instead, symbolic acts, monopolies, and administrative assertion became sufficient to justify rule. Greenland thus entered a new phase of European attention, one in which absence was reinterpreted as availability and distance as strategic advantage rather than limitation.

This reconceptualization was not unique to Greenland, but the Arctic intensified its effects. The region’s perceived emptiness, harsh climate, and limited European population encouraged imperial powers to treat it as a space of extraction, surveillance, and future utility rather than lived political life. Greenland became valuable less for what it was than for what it represented: access to northern seas, control over trade routes, scientific prestige, and geopolitical leverage. Indigenous presence, while acknowledged, rarely disrupted this logic. Inuit communities were rendered objects of administration or study, not participants in sovereignty.

The consequences of this transformation extend well beyond the early modern period. By the nineteenth century, imperial reasoning had hardened into a durable grammar of possession that framed Arctic lands as assets to be managed, traded, or defended. That grammar has proven remarkably persistent. Contemporary rhetoric that treats Greenland as negotiable property rather than a political community echoes the assumptions forged during Europe’s age of empire. Understanding how Greenland became an imperial object is therefore not merely a matter of historical reconstruction. It is essential for recognizing how colonial logics continue to shape modern debates about sovereignty, security, and power in the Arctic.

Early Modern Europe and the Rediscovery of Greenland (16th–17th Centuries)

Greenland’s so-called rediscovery in the sixteenth century did not involve physical conquest or sustained European settlement. Instead, it unfolded through texts, maps, and inherited claims that reinserted the island into European consciousness after centuries of relative obscurity. Medieval Norse memory, preserved in sagas and ecclesiastical records, provided a thin but potent foundation. Early modern Europe did not encounter Greenland as an unknown land but as a place already claimed, one whose political status could be revived without renegotiation. This revival depended less on presence than on narrative continuity.

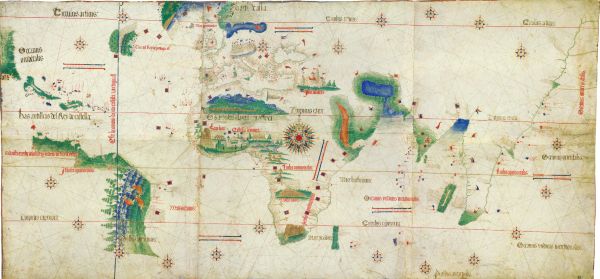

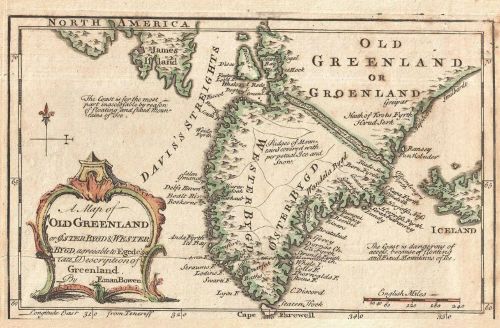

Cartography played a central role in this process. Sixteenth century maps increasingly fixed Greenland’s outline and location, often with little empirical accuracy but considerable symbolic force. To appear on a map was to exist within a European order of space and power. Greenland’s depiction alongside other northern lands reinforced the assumption that it belonged within the orbit of Christian monarchy and European jurisdiction. These visual representations did not merely reflect knowledge. They produced it, transforming geographic uncertainty into cartographic certainty that could be cited as evidence of possession.

Exploration literature further contributed to this reimagining. Accounts by sailors, traders, and diplomats circulated descriptions of the Arctic as both hostile and promising. Greenland emerged in these narratives as a land defined by extremes, inhospitable yet strategically significant. Its value lay not in immediate colonization but in its potential role within northern trade networks and maritime routes. The absence of permanent European populations was not interpreted as a weakness of claim. Instead, it reinforced the notion that sovereignty could precede settlement and even substitute for it.

Danish and Norwegian rulers drew heavily on these developments to restate authority over Greenland. Their claims emphasized continuity with medieval Christian kingship rather than novelty or conquest. Greenland was framed as a dependency that had temporarily slipped from view rather than a territory requiring acquisition. This rhetorical move allowed early modern monarchs to assert control without confronting the legal or moral questions that accompanied overt colonization elsewhere. Greenland’s distance made it especially amenable to this strategy, as effective oversight could be minimal while symbolic authority remained intact.

The legal imagination of the period supported such assertions. Early modern theories of sovereignty increasingly privileged recognition among states over consent from inhabitants. If other European powers acknowledged Denmark’s claim, the internal political life of Greenland mattered little. Indigenous communities were acknowledged as residents but not as holders of political authority. Their presence did not invalidate European claims, because sovereignty was defined externally, through diplomatic acceptance and inherited precedent rather than local governance.

By the end of the seventeenth century, Greenland had been firmly reabsorbed into Europe’s imperial mental map. This rediscovery did not restore medieval forms of dominion but replaced them with a thinner, more abstract conception of control. Greenland existed as a named, mapped, and claimed territory whose political meaning was determined almost entirely from afar. The groundwork was thus laid for later mercantilist and imperial exploitation, in which possession would be further formalized without ever becoming participatory or reciprocal.

Mercantilism and the Logic of Arctic Possession

By the late seventeenth century, Greenland was increasingly interpreted through the economic doctrines of mercantilism, which reshaped how European powers understood the value of territory. Mercantilist thought emphasized state control over trade, monopolies, and strategic resources, privileging possession over participation. Within this framework, Greenland was not evaluated as a society with political institutions or communal claims but as a reservoir of potential wealth and strategic advantage. Its importance derived from its capacity to serve metropolitan interests rather than from any internal political life.

Arctic resources occupied a distinctive place in mercantilist imagination. Whaling, sealing, fishing, and access to northern maritime routes promised economic return without the costs associated with large scale settlement or agricultural development. Greenland’s harsh environment, once a barrier to integration, now became an advantage. It discouraged rival settlement while still allowing extraction through tightly controlled commercial enterprises. The Arctic thus exemplified a form of possession that maximized monopoly and minimized obligation, aligning neatly with mercantilist priorities.

Chartered companies and royal monopolies became the primary instruments of control. Economic rights were granted by the crown, binding commerce directly to sovereignty. In Greenland’s case, this meant that trade and authority were inseparable. Commercial activity functioned as a proxy for governance, allowing Denmark to assert effective control without extensive administrative infrastructure. The absence of representative institutions or local political participation was not viewed as a deficiency. On the contrary, it reinforced the assumption that governance could be exercised remotely through economic regulation alone.

Mercantilism also narrowed the conceptual space available for recognizing Indigenous agency. Inuit communities were incorporated into economic systems as laborers, intermediaries, or subjects of regulation, but never as political partners. Their knowledge of the Arctic environment was exploited, while their social and political structures were rendered invisible within European economic theory. Mercantilist reasoning thus deepened an earlier tendency to acknowledge Indigenous presence without conceding Indigenous sovereignty, reinforcing the asymmetry between possession and habitation.

By the early eighteenth century, this economic logic had become self-sustaining. Greenland’s value was no longer debated in terms of legitimacy or consent but assumed as a function of utility and exclusivity. Possession justified itself through control of trade, and control of trade confirmed possession. In this closed loop, sovereignty became indistinguishable from monopoly. Greenland was fully embedded in an imperial system that treated Arctic land as an instrument of state power, setting the stage for later colonial administration and international rivalry.

Danish Colonial Administration and the Formalization of Control

By the eighteenth century, Danish authority in Greenland moved beyond inherited claim and mercantile logic toward a more explicit colonial administration. This transition did not involve large scale settlement or the creation of representative institutions. Instead, control was formalized through centralized regulation, commercial monopoly, and bureaucratic oversight directed from Copenhagen. Greenland was administered as a dependency whose political status derived from royal prerogative rather than local governance. Authority was thus present without being participatory, institutional without being inclusive.

Royal monopolies served as the backbone of this administrative system. The crown’s exclusive control over trade effectively merged economic activity with political authority, ensuring that governance flowed through commercial channels. Colonial officials, traders, and missionaries operated within a tightly controlled hierarchy, reinforcing Danish sovereignty through everyday regulation rather than overt coercion. The limited number of European administrators did not weaken the system. On the contrary, the small administrative footprint was treated as evidence of efficient control, minimizing costs while preserving exclusivity.

Ecclesiastical institutions played a critical role in stabilizing colonial rule. Missionary activity was framed as moral obligation, but it also functioned as a mechanism of political consolidation. Conversion, education, and regulation of social life aligned Indigenous communities with Danish authority while discouraging alternative forms of allegiance. The church did not introduce political representation or legal autonomy. Instead, it reinforced a paternalistic structure in which protection and instruction substituted for consent. Sovereignty was expressed through care rather than contract, a formulation that masked asymmetrical power relations.

This administrative model normalized the treatment of Greenland as a governed space without political voice. Colonial order rested on the assumption that legitimacy flowed from royal authority and international recognition rather than from the governed population. Indigenous Greenlanders were managed as subjects rather than citizens, their political existence acknowledged only insofar as it could be supervised. By the late eighteenth century, Danish colonial administration had fully institutionalized Greenland’s status as a possession. Control no longer required justification. It was embedded in routine governance, economic monopoly, and moral guardianship, laying a durable foundation for nineteenth-century imperial thinking.

Empire, Science, and the Arctic as Strategic Space (18th–19th Centuries)

During the eighteenth century, Greenland became increasingly entangled in the scientific ambitions of European empires. Enlightenment inquiry reframed the Arctic not as a marginal wasteland but as a field of knowledge production that could enhance imperial prestige and authority. Measurement, classification, and observation were never politically neutral activities. Expeditions to Greenland contributed to a growing imperial archive in which geography, climate, and natural history were cataloged in service of state power. Science thus functioned as an extension of sovereignty, translating distant landscapes into governable information.

Cartographic precision intensified this transformation. Improved mapping techniques rendered Greenland legible in ways that supported strategic calculation. Coastlines, ice flows, and navigable waters were documented with increasing detail, reinforcing the perception that the Arctic could be known, predicted, and controlled. These representations did not simply reflect exploration. They established claims. To map Greenland was to inscribe it within a European epistemic order that treated territorial knowledge as evidence of authority. Scientific certainty replaced lived experience as the basis for legitimacy.

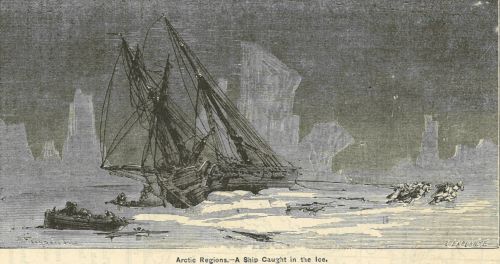

Imperial rivalry sharpened this process. British interest in Arctic exploration during the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries was driven as much by geopolitical signaling as by scientific curiosity. Expeditions demonstrated national prowess, technological capacity, and global reach. Greenland, positioned at the intersection of the North Atlantic and Arctic routes, became a reference point in broader contests over northern access and maritime dominance. Even when formal claims were not advanced, presence itself functioned as a reminder that Arctic space was strategically valuable and perpetually contested.

The emergence of the United States as an Arctic actor in the nineteenth century further reinforced this logic. American expeditions, scientific societies, and commercial interests adopted the same assumptions that had long guided European powers. The Arctic was framed as a frontier of opportunity and influence, its political status secondary to its strategic potential. Greenland appeared in American discourse not as a society or polity but as a location whose control or access might shape future security arrangements. This continuity underscores how imperial reasoning transcended individual empires, becoming a shared language of power.

By the late nineteenth century, the Arctic had been fully absorbed into imperial strategic thought. Greenland’s value was articulated through science, navigation, and projection of influence rather than governance or consent. Knowledge production justified possession, and possession enabled further knowledge production in a reinforcing cycle. The Arctic was no longer distant. It was integrated into imperial systems that treated land as an asset and sovereignty as a function of capability. This transformation cemented Greenland’s role as strategic space, a conception that would persist into the modern geopolitical imagination.

Indigenous Greenlanders and the Colonial Blind Spot

European imperial engagement with Greenland consistently relied on a fundamental contradiction: the permanent presence of Indigenous communities alongside the persistent refusal to recognize them as political actors. Inuit societies were never invisible to colonial authorities. They were encountered, described, regulated, and studied. Yet they were conceptually excluded from the domain of sovereignty. European powers acknowledged Indigenous life while denying Indigenous polity, sustaining a colonial blind spot that allowed possession to coexist with habitation without ethical or legal tension.

Colonial discourse framed Inuit communities primarily through lenses of utility and vulnerability. They were cast as indispensable guides, hunters, and intermediaries in Arctic survival, while simultaneously depicted as culturally static and politically immature. This dual framing justified intervention without negotiation. Indigenous knowledge could be appropriated, but Indigenous authority could not be acknowledged. European administrators and missionaries thus constructed a narrative in which protection replaced consent and instruction supplanted political recognition, reinforcing paternalism as a substitute for sovereignty.

Ethnography and anthropology further entrenched this imbalance. As scientific interest in the Arctic intensified during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Indigenous Greenlanders became subjects of observation rather than participants in governance. Cultural practices were recorded, classified, and preserved in European archives, often presented as remnants of an earlier stage of human development. This scholarly attention did not translate into political inclusion. On the contrary, it reinforced the assumption that Inuit societies belonged to nature or culture, not to politics, placing them outside the frameworks through which sovereignty was debated.

The colonial blind spot endured because it was structurally convenient. Recognizing Indigenous political agency would have complicated European claims grounded in discovery, continuity, and strategic necessity. By denying that complication, imperial powers maintained a clean legal fiction in which Greenland could be possessed without conquest and governed without representation. This legacy persists in modern debates over Arctic sovereignty, where Indigenous presence is frequently acknowledged rhetorically but sidelined substantively. The historical exclusion of Indigenous Greenlanders from political recognition was not an oversight. It was a foundational condition of imperial control.

Nineteenth-Century Imperialism and the Hardening of Possession

By the nineteenth century, European imperialism had developed a more rigid and self-confident understanding of territorial sovereignty, one grounded in international recognition, administrative continuity, and strategic necessity. Greenland’s status within this system was no longer provisional or rhetorical. It was assumed. The island was treated as an established possession whose legitimacy derived from precedent rather than active governance or popular consent. This hardening of possession reflected a broader imperial tendency to treat long-held claims as natural facts, immune to challenge or reinterpretation.

International law played a decisive role in this transformation. Nineteenth century legal thought increasingly prioritized effective occupation and recognition among states over historical justice or Indigenous rights. Greenland’s sparse European population did not weaken Danish claims, because effectiveness was measured administratively rather than demographically. Trade monopolies, missionary presence, and intermittent patrols were sufficient to demonstrate control. Once accepted by other powers, these markers of authority converted assumption into legality. Sovereignty became a matter of paperwork and precedent, not participation.

Imperial competition reinforced this logic. As Britain, Russia, and later the United States expanded their Arctic interests, Denmark’s hold on Greenland was rarely questioned directly. Instead, it was respected as part of the existing imperial order. Challenging Denmark’s claim would have risked destabilizing similar assertions elsewhere. Greenland thus benefited from a kind of imperial mutual recognition, where possession was protected because it mirrored the logic by which all empires operated. Stability among empires took precedence over justice within colonies.

Within Denmark itself, Greenland was increasingly framed as an indivisible component of national and imperial identity. Administrative reforms and symbolic gestures reinforced the idea that sovereignty was permanent and nonnegotiable. Discussions of reform focused on efficiency and welfare, not autonomy or political representation. Indigenous Greenlanders remained subjects of improvement rather than holders of rights. The language of benevolence masked the consolidation of authority, presenting continued possession as both moral and inevitable.

By the end of the nineteenth century, Greenland’s political status had been fully naturalized within imperial thinking. Possession no longer required active defense or ideological justification. It was embedded in legal doctrine, diplomatic practice, and strategic planning. This hardened conception of sovereignty left little room for alternative political futures. Greenland was not imagined as a polity that might negotiate its place in the world, but as a territorial constant within imperial systems. That assumption, forged in the nineteenth century, continues to shape modern debates over Arctic power and ownership.

Conclusion: Imperial Grammar and the Modern Return of Arctic Entitlement

The long European engagement with Greenland reveals a consistent pattern in the exercise of power over Arctic space. From early modern rediscovery through nineteenth-century imperial consolidation, Greenland was progressively abstracted from political community and redefined as an object of strategy, commerce, and prestige. Sovereignty was detached from consent and participation, anchored instead in continuity of claim, administrative gesture, and recognition among rival powers. This transformation did not merely shape colonial governance. It produced a durable grammar of possession that continues to inform how Arctic territory is imagined and discussed.

That grammar rested on a set of assumptions that hardened over time. Land could be claimed without settlement, governed without representation, and defended without political inclusion. Indigenous presence, while acknowledged, was rendered irrelevant to sovereignty itself. Scientific knowledge, economic utility, and strategic positioning replaced older notions of reciprocal obligation. By the nineteenth century, Greenland’s status as a possession appeared self-evident within imperial systems, no longer requiring moral justification or political debate. The island existed as leverage rather than polity, a condition normalized through law, diplomacy, and administrative routine.

This historical framework casts contemporary rhetoric about Greenland into sharp relief. When modern political leaders speak of Arctic land as negotiable, acquirable, or strategically indispensable, they do not innovate new arguments. They revive old ones. The language used by President Donald Trump in reference to Greenland closely mirrors nineteenth-century imperial reasoning, treating territory as an asset whose value lies in security advantage and geopolitical competition rather than in the self-determination of its inhabitants. The persistence of this language underscores how deeply imperial assumptions remain embedded in modern political thought.

Recognizing this continuity is essential for any serious discussion of Arctic sovereignty today. Greenland’s political future cannot be understood solely through contemporary strategic concerns or economic forecasts. It must be situated within a long history in which possession was repeatedly asserted without participation and legitimacy was defined externally rather than internally. To challenge modern entitlement claims requires more than policy disagreement. It requires confronting the imperial grammar that still shapes how Arctic land is imagined, valued, and contested. Only by exposing that grammar can alternative conceptions of sovereignty, grounded in political community rather than imperial inheritance, be meaningfully articulated.

Bibliography

- Anghie, Antony. Imperialism, Sovereignty and the Making of International Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Appleby, Joyce. Economic Thought and Ideology in Seventeenth-Century England. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1978.

- Benton, Lauren. A Search for Sovereignty: Law and Geography in European Empires, 1400–1900. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Bravo, Michael T. North Pole: Nature and Culture. London: Reaktion Books, 2019.

- Brotton, Jerry. Trading Territories: Mapping the Early Modern World. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1997.

- Driver, Felix. Geography Militant: Cultures of Exploration and Empire. Oxford: Blackwell, 2001.

- Gad, Finn. The History of Greenland, Volume I. Earliest Times to 1700. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1971.

- Gosden, Chris. Archaeology and Colonialism: Cultural Contact from 5000 BC to the Present. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Hansen, Lars Ivar, and Bjørnar Olsen. Hunters in Transition: An Outline of Early Sámi History. Leiden: Brill, 2013.

- Heckscher, Eli F. Mercantilism. Translated by Mendel Shapiro. London: George Allen and Unwin, 1935.

- Koskenniemi, Martti. The Gentle Civilizer of Nations: The Rise and Fall of International Law 1870–1960. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- Lemberg, Tia. “Reverse Colonization: How the Inuit Conquered Greenland and Vanquished the Vikings.” Remake 2 (2021).

- Livingstone, David N. Putting Science in Its Place: Geographies of Scientific Knowledge. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003.

- Murawska-Muthesius, Katarzyna. “Mapping Eastern Europe: Cartography and Art History.” Artlas Bulletin 2:2 (2013): 14-25.

- Osterhammel, Jürgen. Colonialism: A Theoretical Overview. Princeton: Markus Wiener Publishers, 1997.

- —-. The Transformation of the World: A Global History of the Nineteenth Century. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009.

- Outram, Dorinda. The Enlightenment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Pagden, Anthony. European Encounters with the New World: From Renaissance to Romanticism. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993.

- —-. Lords of All the World: Ideologies of Empire in Spain, Britain, and France c.1500–c.1800. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995.

- Porter, Andrew. Religion Versus Empire? British Protestant Missionaries and Overseas Expansion, 1700–1914. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2004.

- Quinn, David B. European Approaches to North America, 1450–1640. London: Routledge, 1998.

- Said, Edward W. Culture and Imperialism. New York: Knopf, 1993.

- Seed, Patricia. Ceremonies of Possession in Europe’s Conquest of the New World, 1492–1640. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- Stafford, Robert A. Scientist of Empire: Sir Roderick Murchison, Scientific Exploration and Victorian Imperialism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

- Tester, Frank J., and Peter Kulchyski. Tammarniit (Mistakes): Inuit Relocation in the Eastern Arctic, 1939–63. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1994.

Originally published by Brewminate, 01.28.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.