During the Georgian period a host of entertainments were available to those seeking relief from their everyday routines.

By Dr. Matthew White

Visiting Research Fellow

University of Hertfordshire

Theatre

The 18th century was the great age of theatre. In London and the provinces, large purpose-built auditoriums were constructed to house the huge crowds that flocked nightly to see plays and musical performances. A variety of entertainments were on offer, from plays and ballets to rope-walkers and acrobats.

London’s Drury Lane, Covent Garden and the Haymarket theatres all prospered during the period; by the 1760s, each of these theatres seated several thousand people. This was also the age of the first ‘celebrity’ actors: David Garrick, for example, who was mobbed by fans wherever he travelled in London.

Theatregoing was a very different experience from that of today. Theatre audiences could be rude, noisy and dangerous. Alcohol and food was consumed in great quantity, while people frequently arrived and left throughout the duration of the performance. Audiences chatted amongst themselves and sometimes pelted actors with rotten fruit and vegetables. Others demanded that popular tunes be played over and over again. James Boswell described mooing like a cow during one particularly bad play, to the great amusement of his companions. Rioting at theatres was also not uncommon. The Drury Lane Theatre in London, for example, was destroyed by rioting on six occasions during the century.

Audiences were a mixture of both rich and poor, and sat in different parts of the theatre depending on whether they could afford cheap or expensive tickets. ‘Persons of quality’ were seated in boxes placed alongside the stage, while working men and women were squeezed into hot and dirty galleries. In front of the stage, young men would drink together, eat nuts and mingle with prostitutes down below in the notorious ‘pit’.

Pleasure Gardens

Like the theatre, pleasure gardens were the great melting pots of 18th-century society. London pleasure gardens in particular were incredibly successful. First opened in 1746, Ranelagh Pleasure Gardens in Chelsea boasted acres of formal gardens with long sweeping avenues, down which pedestrians strolled together on balmy summer evenings. Other visitors came to admire the Chinese Pavilion, or watch the fountain of mirrors and attend musical concerts held in the great 200-foot wide Rotunda. Novelist Fanny Burney described how the nightly illuminations and magic lanterns at Ranelagh ‘made me almost think I was in some enchanted castle or fairy palace’.

Originally designed to appeal to wealthier tastes, pleasure gardens soon became visited by rich and poor alike: both aristocrats and tradesmen enjoyed the entertainments side by side. The entrance price to Vauxhall Gardens was just one shilling throughout the century and therefore remained affordable to most people. Some 12,000 people arrived at Vauxhall Gardens in 1749 to watch Handel rehearse his Music for the RoyalFireworks. Elsewhere in London, people drank tea and strolled together in smaller private venues, of which there were over 60 by the second half of the century. Most provincial towns also boasted their own pleasure gardens that were often modelled on the most fashionable London attractions.

Fairs

In most towns across the country, fairs and traditional holidays remained important parts of the yearly calendar. Wakes were traditional fairs linked to local saints’ or feast days, while other fairs accompanied markets and civic celebrations. Many fairs lasted for a week or more, and were attended by thousands of people, who hurried to attend them from across the surrounding area.

Most fairs were much more than simple markets. Bartholomew Fair was by far the largest and most spectacular event of its kind, and was the scene of much public excitement. Held in London every September for four days, the thousands of visitors who went there could witness dozens of entertainments and spectacles: tumbling, acrobatics and tightrope walking, for example, or exhibitions of exotic animals, boxing competitions, puppet shows and displays of human strength. Fairs were also the scene of much eating and drinking. There were dozens of ‘booths’ selling a vast array of foods, such as gingerbread, nuts, puddings, sausages and hot pies, to the huge crowds. Vast quantities of alcohol were consumed, which was the cause of much concern to local authorities.

Curiosities, Exhibitions, and Crazes

Exhibitions of curiosities regularly drew large crowds of fascinated sightseers. Up and down the Strand in London, exhibitions of imported exotic animals could be seen in taverns and assembly rooms: birds and monkeys from Africa, for example, or even lions, tigers and zebras.

Other animals were trained to perform tricks for the amusement of the general public. At the end of the century, the famous ‘performing pig’ became famous across the country for its apparent ability to spell, while elsewhere one could watch trained bees or birds obey human commands.

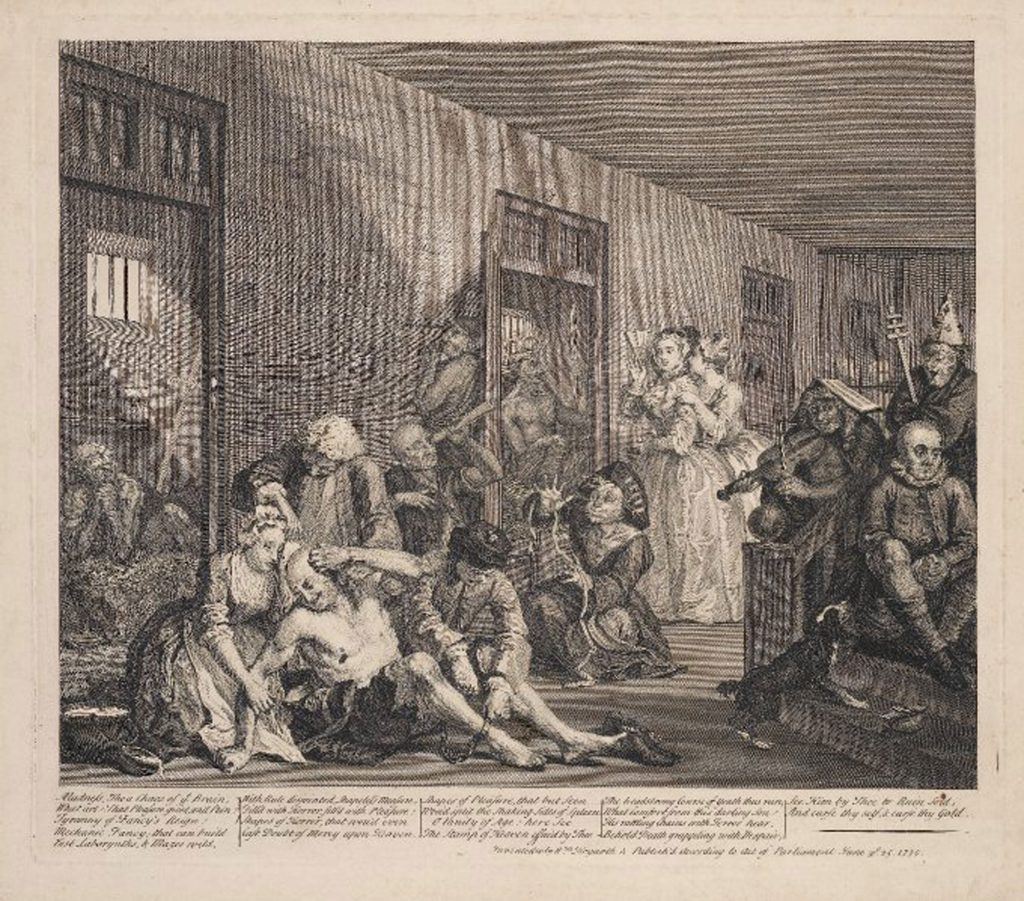

Human curiosities proved just as exciting to the public. For decades, London’s hospital for the insane – Bethlehem, or Bedlam – attracted queues of gawping sightseers, who were eager to watch the behaviour of inmates afflicted with mental illnesses.

But other human curiosities were also available. Giants, midgets, the obese, natives of foreign countries and a host of sufferers of various medical conditions were all put on display to the public, who were willing to pay a few pennies to see the latest offerings.

Scientific spectacles also attracted widespread public interest. In 1784 the first manned hot air balloon flight was made in England by an Italian aviator, Vincenzo Lunardi, whose appearance over the rooftops of London caused an outright sensation. From that point on, regular balloon flights brought crowds of several thousand onlookers whenever take-offs were expected, and ‘balloonomania’ swept right across the country. ‘The term balloon is not only in the mouth of every one’, noted one witness to the craze, ‘but all our world seems to be in the clouds’.

Blood Sports

Animal baiting and organised blood sports remained extremely popular during the 18th century. Bull baiting was one such example; the animal was tied to a stake as dogs were sent in to attack, while a cheering and expectant crowd watched from the sidelines. Many provincial towns had specific bullrings built for this purpose, and baitings often took place in busy marketplaces or town squares. Badgers and bears were also occasionally used in this manner. Alternatively, bull-running was often organised in towns. Angry bulls were sometimes set free in the streets, and pursued from place to place by crowds of excited spectators.

Cockfighting was also popular amongst all the social classes. Large crowds gathered at custom-built cockpits in order to watch specially reared birds fight one another to the death. Two birds were fitted with sharpened spurs on each leg while huge bets were placed on them. These spectacles could be particularly vicious. After attending a cockfight in 1762 James Boswell noted how the birds fought with ‘amazing bitterness and resolution’ to the very end.

The popularity of many blood sports began to disappear by the end of the century. They became less frequent due to changing attitudes to animal rights. Animal baiting was eventually made illegal by Parliament early in the 1800s.

Originally published by the British Library, 10.14.2009, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.