Many important Roman cities had an arena which hosted thrilling chariot races and more for public entertainment.

By Mark Cartwright

Historian

Introduction

The Hippodrome of Constantinople was an arena used for chariot racing throughout the Byzantine period. First built during the reign of Roman emperor Septimius Severus in the early 3rd century CE, the structure was made more grandiose by emperor Constantine I in the 4th century CE. The Hippodrome was also used for other public events such as parades, public executions and the public shaming of enemies of the emperor. Following the Fourth Crusade in the early 13th century CE, the Hippodrome fell out of use and its spectacular monuments and artworks were looted.

A Sporting Arena

Many important Roman cities had an arena which, like the Circus Maximus of Rome, hosted thrilling chariot races for public entertainment. Byzantium (which would become Constantinople) was no exception, and Emperor Septimius Severus (r. 193-211 CE) funded the building of one there in the 3rd century CE. Constantine I (r. 306-337 CE) understood that the Hippodrome provided an unrivalled opportunity to show the people the emperor’s power, wealth, and generosity in lavish public entertainments that went on for days at a time, often coinciding with public holidays. Consequently, he not only refurbished and extended the old circus when he switched the empire’s capital from Rome but he made sure to hand out cash and clothes to the crowd at his first race event. Located in the heart of the city right next to the Great Palace, which was the imperial residence, Constantine ensured there was even a connecting stairway between the two buildings to provide a physical link between the emperor and his well-entertained people.

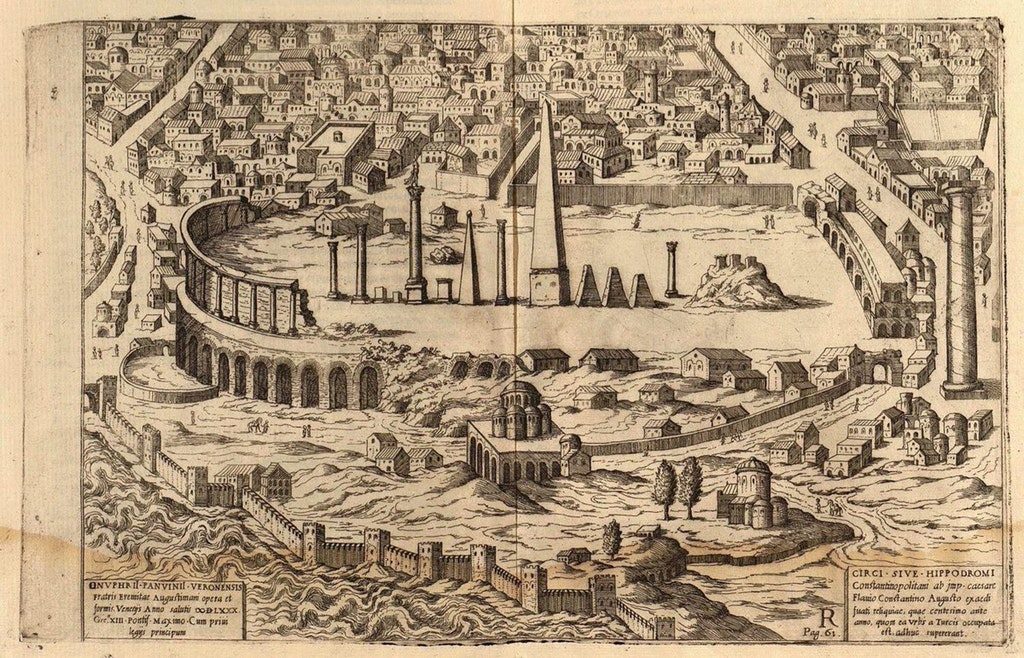

The Hippodrome was the typical long rectangular shape with a curved end seen elsewhere in the Roman Empire. It was around 400 metres (1300 feet) in length and up to 200 metres wide. One lap of the track would have measured around 300 metres (1000 feet). Historians cannot agree on the seating capacity, and estimates range from 30,000 to over 60,000 people. VIPs had marble seats in the front rows while everyone else made do with wooden benches, although cushions could be hired from hawkers. The seating tiers rose 12 metres (40 feet) high above the track and were separated from it by a moat. The monumental entrance gate, the Carceres, was topped by a gilded bronze chariot group. In 1204 CE, during the Fourth Crusade when Constantinople was sacked, the four horses from this sculpture were looted. They are probably those which were taken to Venice, where they still reside today, in the Cathedral of St Mark.

The chariots had to race around a central island or spinaseven times. The spina was a veritable museum of miscellaneous art clutter looted from across the empire with monumental sculptures of early Roman emperors and figures associated with victory such as eagles and the Greek hero Hercules. The central island was further embellished with a number of obelisks, including a false one made of individual blocks but entirely covered in bronze sheeting, and several columns, including the famous bronze Serpent Column of the Plataian tripod, a 5th-century BCE dedication looted from the sacred sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi. The column is formed from the entwined bodies of three snakes and was once 8 metres tall; the lower portion of it still stands today in Istanbul. The more celebrated charioteers had their own monuments here, too, such as the early 6th-century CE racer Porphyrius whose marble statue base still survives.

Most impressive of all of the spina’s antique collection was an Egyptian obelisk removed from Karnak and dating to the reign of Thutmose III in the 15th century BCE. The monument, measuring 25.6 metres in height, was probably erected in the Hippodrome by Theodosius I to commemorate his victory over the usurpers Maximus and Victor in 389 CE, although it had been lying horizontally at the site for some time before. The base on which the obelisk stood was made of marble and decorated with relief scenes showing the emperor watching the chariot races and surrounded by his family and bodyguards.

The chariot races – ranging from 8 to 25 over a particular games – were hugely popular with the masses and the charioteers were acclaimed as heroes, or at least those who won on a regular basis were. Charioteers raced in three different categories of youths aged under 17, young men between 17 and 23, and men over 23 years of age. Betting, of course, added a little extra spice to the proceedings for many spectators. just as these days people head to the best real money casino sites. Musicians, dancers, acrobats, and animal trainers amused the crowd during race intermissions. Emperors regularly attended, too, seating themselves in the plush seats of the imperial box or kathisma. To add even more interest to the races the four charioteers involved in each race represented four different factions which were represented by different colours: Blue, Green, Red, and White. There does not seem to have been any political or social significance to each faction, and so they functioned merely as a group of convenience that anyone could join and support. The factions were very much like the more fanatical sections of modern football stadiums, as the historian T. E. Gregory explains:

…the fans often engaged in organised chants or shouts, they commonly wore outlandish and immediately identifying clothes and haircuts, and they sometimes engaged in violence, especially against members of opposing factions. This violence not uncommonly spilled outside the hippodrome into the streets. (133)

An Arena for Commemoration

The Hippodrome also hosted important festivals and commemorative events. The most important and most enduring was the anniversary of the founding of the city by Constantine I. Held every 11th of May, starting in 323 CE and continuing for a thousand years, the city’s population gathered to celebrate the birth of what became the greatest city in the Mediterranean region. No doubt all the spoils of war which were hung around the Hippodrome as decoration served to remind of all the peoples the Eastern Empire had conquered since that day.

Justinian I (r. 527-565 CE), always partial to a bit of public spectacle, rewarded his gifted general Belisarius with a triumph for his victories against the Vandals in North Africa in 533 CE. This was a great honour as no one outside the imperial family had been allowed to celebrate a Roman triumph since 19 BCE, and it was to be held in the Hippodrome. Belisarius, in full gleaming armour and with his face painted red, rode his chariot around the arena, followed by a selection of the most impressive Vandal captives, their insignia, and a lengthy train of booty which included jewelled chariots, gold thrones, and all the loot the Vandals themselves had swiped following their attack on Rome.

An Arena of Punishment

The base of the Hippodrome’s Karnak obelisk mentioned above reveals that other events besides sporting and commemorative ones were held there. On one side of the base there are prisoners cowering before their emperor, probably about to be executed. On another side there are barbarian captives offering tribute to their new sovereign. The arena saw many other scenes of imperial punishment besides the execution of criminals. The opportunity for rulers to show the people who was boss and what happened to any challengers to that idea was too good to resist. For example, Constantine V (r. 741-775 CE) had faced a coup at the beginning of his reign when a military governor named Artabasdos, backed by the bishop of Constantinople Anastasios, took over the capital in 743 CE. Constantine’s army quickly quashed the rebellion and retook Constantinople for the emperor. As punishment, Anastasios was publicly whipped and sent naked around the Hippodrome riding backwards on a donkey. Artabasdos faired even worse and was blinded along with his two sons in a public ceremony held, again, in the Hippodrome.

Constantine V, in his drive to banish icons from the Church, also used the arena to humiliate monks and clergy who opposed him, forcing them to parade around the spina, holding the hands of nuns while the public spat on them from above. The imperial use of public mockery as a political weapon and the huge crowd of the Hippodrome seemed made for each other – the two would be used in combination by many emperors.

A Social and Political Arena

The colour factions of Constantinople’s Hippodrome commanded great loyalty from supporters and fierce rivalry from competitors. The Blues and Greens, who dominated the 5th and 6th century CE, were particularly known for their violence and general hooliganism. Indeed, it was one of the responsibilities of the Eparch, a high-ranking city official, to supervise the factions, such was their reputation for misconduct. Besides a sporting role, the factions were also called on as a means to organise the defence of the city’s walls if necessary. Supporter groups were not shy of politics either, and they often backed popular causes, using the Hippodrome as a forum to raise awareness of issues they felt strongly about. Even the emperor, if rumoured to be guilty of an indiscretion or abuse, could be railed in the arena which was the place most likely for ordinary people to see their ruler.

There were occasions when the factions got completely out of control, notably the infamous riots of the Nika Revolt of 11-19th January 532 CE. The real causes for complaint were Emperor Justinian I’s tax hikes and his general autocracy, but the riot was sparked by the emperor’s refusal to pardon Blue and Green supporters for a recent outburst of violence in the Hippodrome. The troublemakers joined forces for once, and using the ominous chant “Conquer!” (Nika), which they usually screamed at the particular charioteer they were supporting in a race, they organised themselves into an effective force. The trouble began with Justinian’s appearance in the Hippodrome on the occasion of the opening races of the games. The crowd turned on their emperor, the races were abandoned and the rioters spilt out of the Hippodrome to rampage through the city. They left an impressive trail of destruction wherever they marched, burning down the Church of Hagia Sophia, the Church of Saint Irene, the baths of Zeuxippus, the Chalke gate, and a good portion of the Augustaion forum including, significantly, the Senate House. The starting point of all this destruction, the Hippodrome, escaped with only minor damage.

The riot had become a full-scale rebellion and Hypatios, the general and nephew of Anastasius I (r. 491-518 CE), was crowned in the Hippodrome as the new emperor by the rioters. Justinian was not to be so easily pushed from his throne, though, and his generals Belisarius and Mundus ruthlessly quashed the revolt by slaughtering 30,000 of the perpetrators inside the Hippodrome. Hypatios, who had not actually wished to be crowned by the rioters, was executed nonetheless. No games were held in the Hippodrome for several years after the crisis. It is significant, too, that from the 7th century CE the factions were curtailed and only permitted for ceremonial purposes. Clearly, emperors were wary of mixing sport and politics. Finally, Leo III (r. 717-741 CE) used the Hippodrome as a forum in which to make solemn announcements. Previously, these had been made to a select gathering known as the silention, but Leo expanded his audience to as many people as could squeeze into the arena.

Decline

From the 7th century CE, the number of races held in the hippodrome declined, like in many others across the empire as the Roman culture wained, but it still hosted some up to the 9th century CE. Public events such as executions and festivals continued there until the 13th century CE and the Fourth Crusade attack on the capital when the monuments were stripped from the arena. The Hippodrome has long since disappeared, its building materials cannibalised for other structures, but its outline is clearly marked out, several metres above the original level, in the form of a public park complete with what remains of the serpent column and two original obelisks in modern downtown Istanbul.

Bibliography

- Bagnall, R.S. The Encyclopedia of Ancient History. (Wiley-Blackwell, 2012)

- Brownworth, L. Lost to the West. (Broadway Books, 2010).

- Gregory, T.E. A History of Byzantium. (Wiley-Blackwell, 2010).

- Guberti Bassett

- , S., “The Antiquities in the Hippodrome of Constantinople,” Dumbarton Oaks Papers Vol. 45 (1991): 87-96.

- Herrin, J. Byzantium. (Princeton University Press, 2009).

- Mango, C. The Oxford History of Byzantium. (Oxford University Press, 2002).

- Norwich, J.J. A Short History of Byzantium. (Vintage, 1998).

- Rosser, J. H. Historical Dictionary of Byzantium. (Scarecrow Press, 2001).

- Schrodt

- , B., “Sports of the Byzantine Empire,” Journal of Sport History Vol. 8, No. 3 (Winter, 1981): 40-59.

- Shepard, J. The Cambridge History of the Byzantine Empire c.500-1492. (Cambridge University Press, 2009).

Originally published by the Ancient History Encyclopedia, 11.28.2017, under a Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.